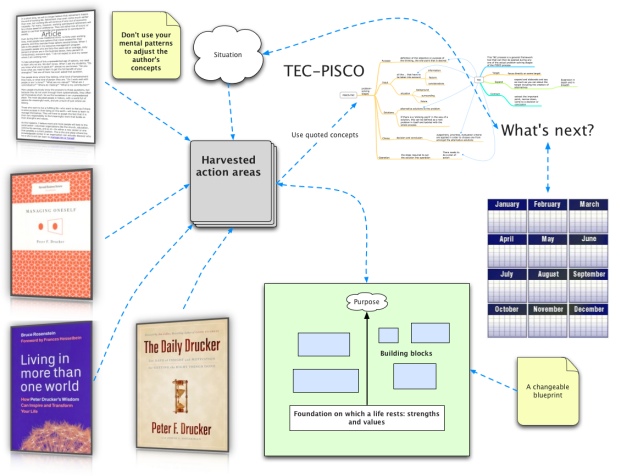

Time investing needs a radar list and regular reviews. Topics, notes and sources can be captured and calendarized.

Years ago I was responsible for the hands-on corporate restructuring work for a company with 90 operating divisions and 45,000 employees. Now more than eighty percent of the divisions and employees are gone. I never met anybody looking for the roads ahead. At the time I was doing this work, I began to explore what I wanted to do next and the "design" of my future life. At some point I realized that I wanted something genuinely interesting to do every day for the rest of my life—something that couldn't be taken away from me. I don't want to just sit around waiting to die. So maybe we have a shared horizon …

My experiences—along with some later financial investing work—lead me to exploring the non-linear ways in which the world of work unfolds and the different situations in which people are embedded.

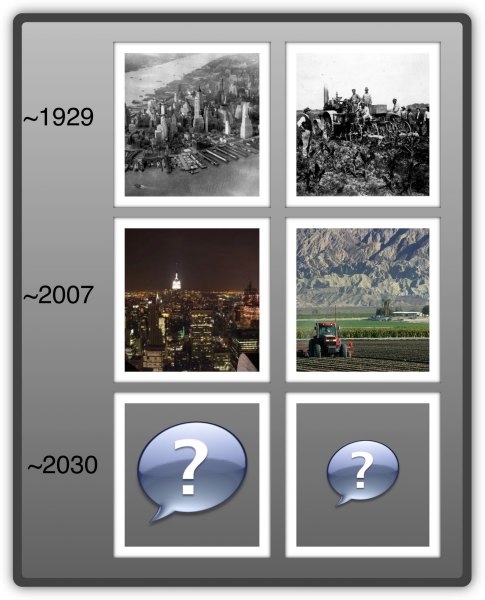

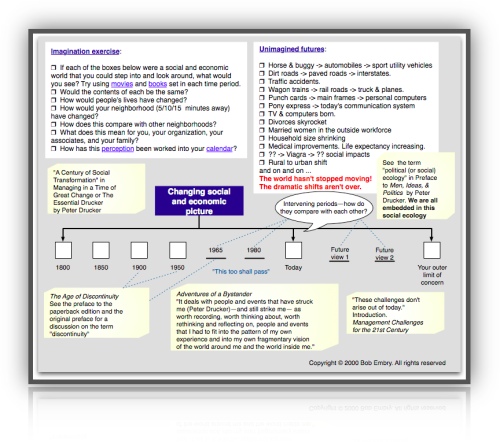

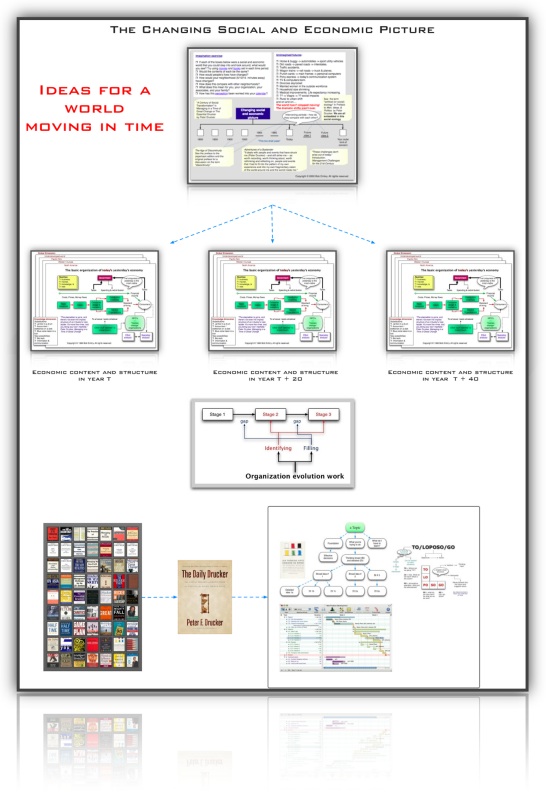

Consider the image above … Few people are even remotely aware—in an informed action oriented sense—that they are embedded in a world moving toward unimagined futures …

The Limping Middle Class

… I reached the conclusion that some kind of conscious, informed time investment process is needed. The best time to work on it is when a person is successful.

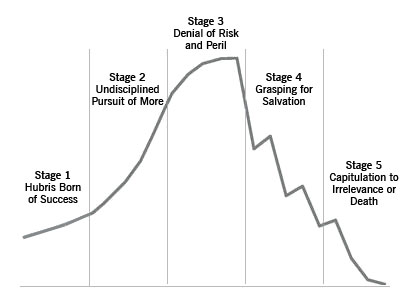

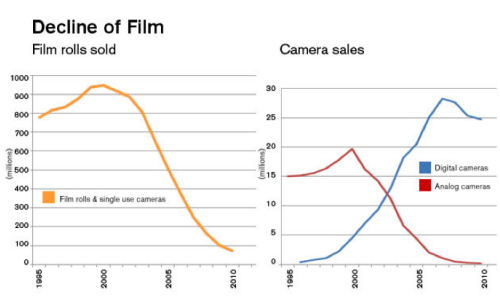

Basing one's dreams, ambitions, plans and actions on what others around them are doing rests on some disastrous assumptions. Employees in HP's personal computer business never imagined what was going to happen. They based their actions on assumptions grounded in the world behind them (product-driven businesses filling a vacuum that no longer exists). Consider the situation at Kodak or Louis Gerstner's experiences with IBM and Sony. Many of the companies mentioned in Built to Last and In Search of Excellence also suffered from the delusion that good current performance equals good future performance. There are countless stories like this—going back decades. Success always obsoletes the very behavior that created it—its just a matter of time. Everything eventually outlives its usefulness. This means that going to work every day under the assumption that doing great routine task work is sufficient will likely end badly. These were not companies that were strapped for resources. They had plenty of people with lots of credentials. Also to state the obvious: all of their activities and efforts failed them. These activities include their marketing, innovation efforts, strategic planning, employee and management development. So were they wasting time and money on these activities?

Below are links to pages on my site. These topics are attention-directing tools. They may help you locate where you want to be in the future. They act as a work "menu" for navigating your way to the worlds of 2020, 2030 … They give you something to actively explore, consider, harvest and review in designing your way forward. There is no way to get to tomorrows by just piling up more todays—routine tasks. It requires time investments—at recurring intervals.

There is no shortage of people promoting ideas in this area. So part of time investing involves separating the good from the ill-informed, fads, and fraudsters.

By superimposing various advice on the worlds of yesterdays and then testing to see if it produces a healthy today (and tomorrows), is one litmus test.

Imagine a 1950s or 1970s or 1990s organization and someone implies that X idea (the advice) will lead to a healthy future (2010, 2020). Flash forward. Looking at the extrapolated situation in today's world does it seem like idea X was the right thing to do—why or why not.

Getting a list of prominent organizations from years ago and exploring their evolution should be a part of everyone's education. How The Mighty Fall: And Why Some Companies Never Give In

For many years I've been a great admirer and follower of Peter Drucker's and Edward de Bono's work—for different reasons. Both are the best I've run across. Introductions and overviews to their work—along with a few others—are major parts of my site. The rest of my site mainly involves contexts and action thinking—connecting the dots.

The world has become a constantly evolving network of discontinuous roads—new roads emerge and old roads decay …

As an example consider the unfolding means (over decades) of making, distributing, and viewing a movie. Many of the developments were dependent on developments completely disconnected from movie making.

If you are a fan of David Allen's Getting Things Done, you might want to test how adequately it deals with the issues presented here.

What about living one's dreams or the prevalent advice on setting goals? Neither of these is bad, but they are normally presented as isolated ideas divorced from reality. Seriously evil people have dreams and goals. Hilter, Stalin, and Mao had dreams and goals. Every bankrupt organization contains people with dreams and goals. I encourage you to think about it. People need direction based on …

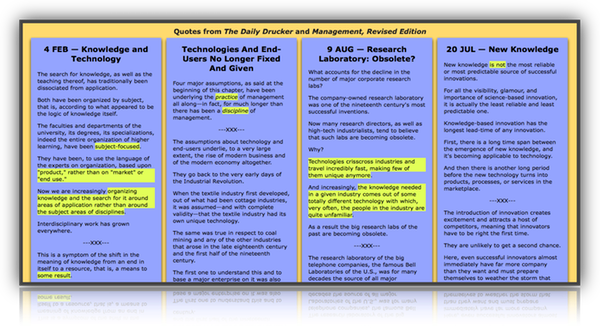

Following is from Post-Capitalist Society by Peter Drucker

Amazon link: Post-Capitalist Society

“EVERY FEW HUNDRED YEARS in Western history there occurs a sharp transformation.

We cross what in an earlier book (The New Realities—1989) I called a “divide.”

Within a few short decades, society rearranges itself—its worldview; its basic values; its social and political structure; its arts; its key institutions.

(Can you identify what these components might be?)

(calendarize this?)

Fifty years later, there is a new world.

And the people born then cannot even imagine the world in which their grandparents lived and into which their own parents were born.

We are currently living through just such a transformation.”

The Limping Middle Class

“It is creating the post-capitalist society, which is the subject of this book.”

“That knowledge has become the resource,

rather than a resource,

is what makes our society “post-capitalist.”

This fact changes—fundamentally—the structure of society.

It creates new social and economic dynamics.

It creates new politics.

The post-capitalist society

is both a knowledge society and a society of organizations,

each dependent on the other and yet

each very different in its concepts, views, and values.

It is the very nature of knowledge

that it changes fast

and that today’s certainties

will be tomorrow’s absurdities.” — PFD

Chapter 3 — Labor, Capital, and Their Future

If knowledge is the resource of post-capitalist society, what then will be the future role and function of the two key resources of capitalist (and socialist) society, labor and capital?

Socially, the new challenges will predominate.

(to be discussed in Chapters 4 “The Productivity of the New Workforces” and 5 “The Responsibility Based Organization” and in the last part of this book — Knowledge: Its Economics and Its Productivity; The Accountable School; The Educated Person)

And the success of post-capitalist society will largely depend on our answers to them.

But politically, the unfinished business of capitalist society will be highly visible: the disappearance of labor as a factor of production, and the redefinition of the role and function of traditional capital.

We have moved already into an “employee society” where labor is no longer an asset.

We equally have moved into a “capitalism” without capitalists—which defies everything still considered self-evident truth, if not “the laws of nature,” by politicians, lawyers, economists, journalists, labor leaders, business leaders; in short, by most everybody regardless of political persuasion.

For that reason, these issues will be in the political spotlight in the decades ahead.

To be able to tackle successfully the new challenges of this transition period, we must resolve these two items of unfinished business: the future role and function of labor, and the future role and function of money capital.

See articles in the news for examples.

“THE NEW CHALLENGE facing the post-capitalist society is the productivity of knowledge workers and service workers.” (calendarize this?)

“To improve the productivity of knowledge workers will in fact require drastic changes in the structure of the organizations of post-capitalist society, and in the structure of society itself” (managing oneself).

“Even more drastic, indeed revolutionary, are the requirements for obtaining productivity from service workers”

Economic stagnation and severe social tension from

failure to raise knowledge and service worker productivity

Chapter 19 in Management, Revised Edition

Chapter 5 in Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Knowledge: Its Economics and Productivity

For clues to navigating toward tomorrowS … (calendarize these?)

Management’s New Paradigm Management’s New Paradigm

Management Challenges for the 21st Century Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Managing In The Next Society Managing In The Next Society

The Next Society from the Economist

From Analysis to Perception — The New Worldview From Analysis to Perception — The New Worldview

The question of the right size for a given task or a given organization will become a central challenge.

In an information-based society, bigness becomes a “function” and a dependent, rather than an independent, variable.

Increasingly, therefore, the question of the right size for a task will become a central one.

All of them are needed, but each for a different task and in a different ecology.

The right size will increasingly be whatever handles most effectively the information needed for task and function.

See Strategies and Structures in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

Peter Drucker ::: political / social ecologist

The Über Mentor

Remembering Peter Drucker

(from the November 2009 issue of The Economist)

“To know something,

to really understand something important,

one must look at it from sixteen different angles.

People are perceptually slow,

and there is no shortcut to understanding;

it takes a great deal of time.”

discontinuity ::: the black cylinder experiment and its relevance ::: beyond the numbers

… but the only thing that is “new” about political ecology is the name.

As a subject matter and human concern, it can boast ancient lineage, going back all the way to Herodotus and Thucydides.

It counts among its practitioners such eminent names as de Tocqueville and Walter Bagehot.

Its charter is Aristotle’s famous definition of man as “zoon politikon,” that is, social and political animal.

As Aristotle knew (though many who quote him do not), this implies that society, polity, and economy though man’s creations, are nature to man, who cannot be understood apart from and out of them.

It also implies that society, polity and economy are a genuine environment, a genuine whole, a true “system,” to use the fashionable term, in which everything relates to everything else and in which men, ideas, institutions, and actions must always be seen together in order to be seen at all, let alone to be understood.

Political ecologists are uncomfortable people to have around.

Their very trade makes them defy conventional classifications, whether of politics, of the market place, or of academia.

“Political ecologists” emphasize that every achievement exacts a price and, to the scandal of good “liberals",” talk of “risks” or “trade-offs,” rather than of “progress.”

But they also know that the man-made environment of society, polity, and economics, like the environment of nature itself, knows no balance except dynamic disequilibrium.

Political ecologists therefore emphasize that the way to conserve is purposeful innovation—and that hardly appeals to the “conservative.”

Political ecologists believe that the traditional disciplines define fairly narrow and limited tools rather than meaningful and self-contained areas of knowledge, action, and events—in the same way in which the ecologists of the natural environment know that swamp or the desert is the reality and ornithology, botany, and geology only special-purpose tools.

Political ecologists therefore rarely stay put.

It would be difficult to say, I submit, which of chapters in this volume are “management,” which “government” or “political theory,” which “history” or “economics.”

The task determines the tools to be used: but this has never been the approach of academia.

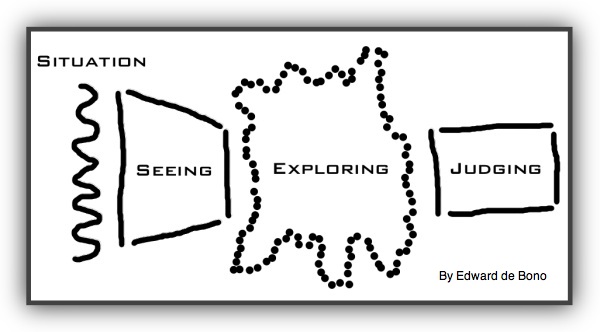

From analysis to perception — the new world view

Form and Function Connections: see chapters

On Being the Right Size and On Being the Wrong Size

in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices and others.

Students of man’s various social dimensions—government, society, economy, institutions—traditionally assume their subject matter to be accessible to full rational understanding.

Indeed, they aim at finding “laws” capable of scientific proof.

Human action, however, they tend to treat as nonrational, that is, as determined by outside forces, such as their “laws.”

The political ecologist, by contrast, assumes that his subject matter is far too complex ever to be fully understood—just as his counterpart, the natural ecologist, assumes this in respect to the natural environment.

But precisely for this reason the political ecologist will demand—like his counterpart in the natural sciences—responsible actions from man and accountability of the individual for the consequences, intended or otherwise, of his actions.

They aim at an understanding of the specific natural environment of man, his “political ecology,” as a prerequisite to effective and responsible action, as an executive, as a policy-maker, as a teacher, and as a citizen.

Not one reader, I am reasonably sure, will agree with every essay; indeed, I expect some readers to disagree with all of them.

by bobembry: Carefully reading his writings is a time-investment — an opportunity to travel a brainroad and create a mental landscape (brainscape).

Having the ability to revisit one of these provides a brainaddress — a way back to a brainscape.

In this case the brainroad is the mental terrain you covered during your reading.

The brainscape is the entire topic landscape.

Creating a brainaddress will take a little thinking.

Your collection of bookmarks is a set of brainaddresses.

Which ones are truly valuable?

Which ones will mean something ten years from now?

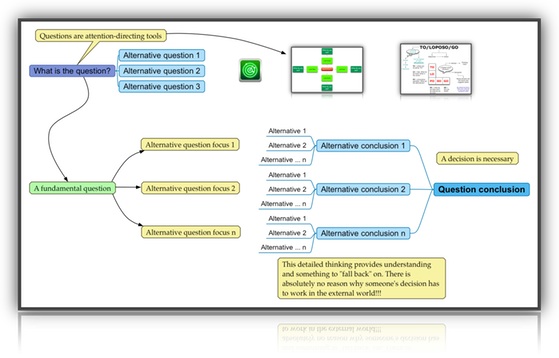

But then I long ago learned that the most serious mistakes are not being made as a result of wrong answers.

The truly dangerous thing is asking the wrong questions.

Men, Ideas & Politics

Questions are attention-directing tools

Larger

read more about social ecology

Good intentions: the road to hell

The mistake most people make when they move into the second half is to rely on good intentions

According to Peter, good intentions (“I want to do something significant”) is only a starting point.

The goal is results and performance that fulfills a clearly stated mission—something that needs doing—something that creates value for a customer (something that is important to them as human beings—not the typical marketing BS).

Peter told me over and over, “All results are on the outside.

On the inside is only cost and effort.”

… Another phrase I heard over and over in virtually every conversation with Peter has shaped my thinking: From good intentions to results and performance.”

Peter contended that most nonprofit organizations, almost all big foundations, and a good deal of government spending are invested in “good intentions.”

Outspoken About Outcomes for Nonprofits

Leap of Reason: Managing to Outcomes in an Era of Scarcity

How to guarantee non-performance

What results should you expect? — a user’s guide to MBO

In his typically brusque style, he once told me, “Tell your rich friends money has no results

If money were what made the difference, Egypt would be Japan.”

Peter wasn’t speaking against money.

He was simply saying that money alone won’t get results.

It might even impede results.

Bob Buford

Beyond Halftime

At some point, you might want to search through this page for the word stem "result" and then the word stem "perform"

A Servant of the Task

The last basic competence is the willingness to realize how unimportant you are compared to the task (of the organization).

Leaders need objectivity, a certain detachment.

They subordinate themselves to the task, but don't identify themselves with the task.

The task remains both bigger than they are, and different.

The worst thing you can say about a leader is that on the day he or she left, the organization collapsed.

When that happens, it means the so-called leader had sucked the place dry.

He or she hasn't built.

They may have been effective operators, but they have not created vision

Keep your eye on the task, not on yourself.

The task matters, and you are a servant.

Chapter 2, "Leadership Is a Foul-Weather Job"

Managing the Non-Profit Organization

Bob Buford's Half Time series

Half Time / Halftime: Changing Your Game Plan from Success to Significance Half Time / Halftime: Changing Your Game Plan from Success to Significance

Beyond Halftime: Practical Wisdom for Your Second Half Beyond Halftime: Practical Wisdom for Your Second Half

Game Plan Game Plan

Stuck in Halftime / Half Time Stuck in Halftime / Half Time

about Leadership about Leadership

CEO work area landscapes CEO work area landscapes

Board-membership Board-membership

The Five Most Important Questions You Will Ever Ask About Your Organization (converts intentions into action) by Peter Drucker The Five Most Important Questions You Will Ever Ask About Your Organization (converts intentions into action) by Peter Drucker

The Definitive Drucker The Definitive Drucker

Management Alert by Mike Kami Management Alert by Mike Kami

See chapter 3 "Source: The Unexpected" in Innovation and Entrepreneurship for the highest probability and easiest road to innovation. (calendarize both the harvesting and implementation?) Involves the intersection between change and the patterning system of the mind See chapter 3 "Source: The Unexpected" in Innovation and Entrepreneurship for the highest probability and easiest road to innovation. (calendarize both the harvesting and implementation?) Involves the intersection between change and the patterning system of the mind

What Executives Should Remember (a PDF summary — to dig deeper search Drucker book contents — calendarize this?) What Executives Should Remember (a PDF summary — to dig deeper search Drucker book contents — calendarize this?)

The Theory of the Business The Theory of the Business

Managing for Business Effectiveness Managing for Business Effectiveness

The 90/10 Rule at Yum! Brands

But every analysis of actual allocation of resources and efforts in business that I have ever seen or made showed clearly that the bulk of time, work, attention, and money first goes to 'problems' rather than to opportunities, and, secondly, to areas where even extraordinarily successful performance will have minimal impact on results. (calendarize this?)

One of the hardest things for a manager to remember is that of the 1,000 different situations he or she will be asked to deal with on any given day, only the smallest handful have a shot at moving the enterprise forward in a truly significant way (calendarize this?)

The job of management, then, is to make sure that financial capital, technology, and top talent are deployed where most of the results are and where most of the costs aren't. The temptation often exists, however, to do exactly the opposite

What Businesses Can Learn from Nonprofits What Businesses Can Learn from Nonprofits

The New Society of Organizations The New Society of Organizations

The Information Executives Truly Need The Information Executives Truly Need

Information Challenges

Managing Oneself (see below) Managing Oneself (see below)

They're Not Employees, They're People They're Not Employees, They're People

What Makes an Executive Effective What Makes an Executive Effective

They asked,"What needs to be done?" They asked,"What needs to be done?"

They asked,"What is right for the enterprise?" They asked,"What is right for the enterprise?"

They developed action plans. They developed action plans.

They took responsibility for decisions. They took responsibility for decisions.

They took responsibility for communicating. They took responsibility for communicating.

They were focused on opportunities rather than problems. They were focused on opportunities rather than problems.

They ran productive meetings. They ran productive meetings.

They thought and said "we" rather than "I" They thought and said "we" rather than "I"

High tech is living in the nineteenth century, the pre-management world. They believe that people pay for technology. They have a romance with technology. But people don't pay for technology: they pay for what they get out of technology. The Frontiers of Management

Management’s New Paradigm

AS WE ADVANCE deeper into the knowledge economy, the basic assumptions underlying much of what is taught and practiced in the name of management are hopelessly out of date.

The center of a modern society, economy and community is not technology.

It is not information.

It is not productivity.

The center of modern society is the managed institution.

The managed institution is society’s way of getting things done these days.

And management is the specific tool, the specific function, the specific instrument, to make institutions capable of producing results (on the outside).

The institution, in short, does not simply exist within and react to society.

It exists to produce results on and in society.

… snip, snip …

Management’s concern and management’s responsibility are everything that affects the performance of the institution and its results—whether inside or outside, whether under the institution’s control or totally beyond it.

Management’s New Paradigm (PDF from Forbes)

Edited versions are also contained in

Management, Revised Edition and

Management Challenges for the 21st Century.

Table form for action identification

HTML list

Management brainscape

Competition on the roads ahead

… In the new mental geography created by the railroad, humanity mastered distance. In the mental geography of e-commerce, distance has been eliminated. There is only one economy and only one market.

One consequence of this is that every business must become globally competitive, even if it manufactures or sells only within a local or regional market. The competition is not local anymore—in fact, it knows no boundaries. Every company has to become transnational in the way it is run. Yet the traditional multinational may well become obsolete. It manufactures and distributes in a number of distinct geographies, in which it is a local company. But in e-commerce there are neither local companies nor distinct geographies. Where to manufacture, where to sell, and how to sell will remain important business decisions. But in another twenty years they may no longer determine what a company does, how it does it, and where it does it.

At the same time, it is not yet clear what kinds of goods and services will be bought and sold through e-commerce and what kinds will turn out to be unsuitable for it. This has been true whenever a new distribution channel has arisen. Why, for instance, did the railroad change both the mental and the economic geography of the West, whereas the steamboat—with its equal impact on world trade and passenger traffic—did neither? Why was there no "steamboat boom"?

Equally unclear has been the impact of more recent changes in distribution channels—in the shift, for instance, from the local grocery store to the supermarket, from the individual supermarket to the supermarket chain, and from the supermarket chain to Wal-Mart and other discount chains. It is already clear that the shift to e-commerce will be just as eclectic and unexpected. …

Managing in the Next Society

by Peter Drucker

See Marketing Moves and Chaotics: The Business of Managing and Marketing in the Age of Turbulence

Mission

An institution exists for a specific purpose and mission, a specific social function.

In the business enterprise, this means economic performance.

With respect to this first task, the task of specific performance, business and nonbusiness institutions differ.

In respect to every other task, they are similar.

But only business has economic performance as its specific mission.

It is the definition of a business that it exists for the sake of economic performance.

In all other institutions—hospital, church, university, or armed services—economics is a restraint.

In those institutions, the budget sets limits to what the institution and the manager can do.

In business enterprise, economic performance is the rationale and purpose.

Business management must always, in every decision and action, put economic performance first.

It can justify its existence and its authority only by the economic results it produces.

A business management has failed if it fails to produce economic results.

It has failed if it does not supply goods and services desired by the consumer at a price the consumer is willing to pay.

It has failed if it does not improve, or at least maintain, the wealth-producing capacity of the economic resources entrusted to it.

And this, whatever the economic or political structure or ideology of a society, means responsibility for profitability.

But business management is no different from the management of other institutions in one crucial respect: it has to manage.

And managing is not just passive, adaptive behavior; it means taking action to make the desired results come to pass.

The early economist conceived of the businessman’s behavior as purely passive; success in business meant rapid and intelligent adaptation to events occurring outside, in an economy shaped by impersonal, objective forces that were neither controlled by the businessman nor influenced by his reaction to them.

We may call this the concept of the “trader.”

Even if he was not considered a parasite, his contributions were seen as purely mechanical: the shifting of resources to more productive use.

Today’s economist sees the businessman as choosing rationally between alternatives of action.

This is no longer a mechanistic concept; obviously the choice has a real impact on the economy.

But still, the economist’s “businessman”—the picture that underlies the prevailing economic “theory of the firm” and the theorem of the “maximization of profits”—reacts to economic developments.

The businessperson is still passive, still adaptive—though with a choice among various ways to adapt.

Basically, this is a concept of the “investor” or the “financier” rather than of the manager.

Of course, it is always important to adapt to economic changes rapidly, intelligently, and rationally.

But managing implies responsibility

for attempting to shape the economic environment;

for planning, initiating, and carrying through changes in that economic environment;

for constantly pushing back the limitations of economic circumstances on the enterprise’s ability to contribute.

What is possible—the economist’s “economic conditions”—is therefore only one pole in managing a business.

What is desirable in the interest of economy and enterprise is the other.

And while humanity can never really “master” the environment, while we are always held within a tight vise of possibilities, it is management’s specific job to make what is desirable first possible and then actual.

Management is not just a creature of the economy; it is a creator as well.

And only to the extent to which it masters the economic circumstances, and alters them by consciously directed action, does it really manage.

To manage a business means, therefore, to manage by objectives

Chapter 3, Management, Revised Edition

Also see chapters: "If You Keep Doing What Worked in the Past You're Going to Fail" and "What Everybody Knows Is Frequently Wrong" in A Class With Drucker: The Lost Lessons of the World's Greatest Management Teacher

Managing Service Institutions in the Society of Organizations

From Chapter 12 of Management, Revised Edition

Amazon Links: Management Rev Ed and Management Cases, Revised Edition and Management Cases, Revised Edition

Business enterprise is only one of the institutions of modern society, and business managers are by no means our only managers.

Service institutions are equally institutions and, therefore, equally in need of management.

Some of the most familiar of these institutions are government agencies, the armed services, schools, colleges, universities, research laboratories, hospitals and other health-care institutions, unions, professional practices such as the large law firm, and professional, industry, and trade associations.

They all have people who are paid for doing the management job, even though they may be called administrators, commanders, directors, or executives, rather than managers.

The Multi-Institutional Society

Public-service institutions are supported by the economic surplus produced by economic activity.

They are social overhead.

The growth of the public service institution in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries is the best testimonial to the success of business in discharging its economic task—producing economic surplus.

Yet, unlike the early nineteenth-century university, the service institutions are not a luxury or an ornament.

They are essentials of a modern society.

They have to perform if society and business are to function.

These service institutions are the main expense of a modern society.

Approximately half of the gross national product of the United States (and of most of the other developed countries) is spent on public-service institutions.

Every citizen in the developed, industrialized, urbanized societies depends for survival on the performance of the public-service institutions.

These institutions also embody the values of developed societies.

Education, health care, knowledge, and mobility—not just more food, clothing, and shelter—are the fruits of our society's increased economic capacities and productivity.

Yet the evidence for performance in the service institutions is not impressive, let alone overwhelming.

Colleges, hospitals, and universities have grown larger than an earlier generation would have dreamed possible.

Their budgets have grown even faster.

Yet everywhere they are in crisis.

A generation or two ago their performance was taken for granted.

Today they are attacked on all sides for lack of performance.

Services that the nineteenth century managed successfully with little apparent effort—the postal service, for instance, or the railroads—are today deep in the red and require enormous subsidies.

National and local government agencies are constantly being reorganized for efficiency.

Yet in every country citizens complain loudly of growing bureaucracy in government.

What they mean is that the government agency is being run more for the convenience of its employees than for contribution and performance.

This is mismanagement.

Are Service Institutions Managed?

The service institutions themselves have become "management conscious."

Increasingly they turn to business to learn management.

In all service institutions, manager development, management by objectives, and many other concepts and tools of business management are now common.

This is a healthy sign, but it does not mean that the service institutions understand the problems of managing themselves.

It only means that they begin to realize that at present they are not being managed.

But Are They Manageable?

There is another and very different response to the performance crisis of the service institutions.

A growing number of critics have come to the conclusion that service institutions are inherently unmanageable and incapable of performance.

Some go so far as to suggest that they should, therefore, be dissolved.

But there is not the slightest evidence that today's society is willing to do without the contributions the service institutions provide.

The people who most vocally attack the shortcomings of the hospitals want more and better health care.

Those who criticize public schools want better, not less, education.

The voters bitterest about government bureaucracy vote for more government programs.

We have no choice but to learn to manage the public-service institutions for performance.

And they can be managed for performance.

Managing Public-Service Institutions For Performance

Different classes of service institutions need different structures.

But all of them need first to impose on themselves discipline of the kind imposed by leaders of the institutions in the examples in the previous chapters.

This work involves

attention-directing and

mental patterns

They need to define "what our business is and what it should be." They need to define "what our business is and what it should be."

See "The Theory of the Business" in chapter 8 of Management, Revised Edition and The Five Most Important Questions You Will Ever Ask About Your Organization (converts intentions into action)

They need to bring alternative definitions into the open and consider them carefully. They need to bring alternative definitions into the open and consider them carefully.

They should perhaps even work out some balance between the different and conflicting definitions of mission (as did the presidents of the emerging American universities—see later in this chapter).

They must derive clear objectives and goals from their definition of function and mission. They must derive clear objectives and goals from their definition of function and mission.

They then must set priorities that enable them to select targets, to set standards of accomplishment and performance—that is, to define the minimum acceptable results, to set deadlines, to go to work on results, and to make someone accountable for results. They then must set priorities that enable them to select targets, to set standards of accomplishment and performance—that is, to define the minimum acceptable results, to set deadlines, to go to work on results, and to make someone accountable for results.

They must define measurements of performance—customer-satisfaction measurements for the performance of Medicare services, or the number of households supplied with electric power (a quantity much easier to measure). They must define measurements of performance—customer-satisfaction measurements for the performance of Medicare services, or the number of households supplied with electric power (a quantity much easier to measure).

They must use these measurements to feed back on their efforts. They must use these measurements to feed back on their efforts.

That is, they must build self-control by results into their system.

Finally, they need an organized review of objectives and results, to weed out those objectives that no longer serve a purpose or have proven unattainable. Finally, they need an organized review of objectives and results, to weed out those objectives that no longer serve a purpose or have proven unattainable.

They need to identify unsatisfactory performance and activities that are outdated or unproductive, or both.

And they need a mechanism for dropping such activities rather than wasting money and human energies where the results are poor.

The last requirement may be the most important one.

Without a market test, the service institution lacks the built-in discipline that forces a business eventually to abandon yesterday—or else go bankrupt.

Assessing and abandoning low-performance activities in service institutions, outside and inside business, would be the most painful but also the most beneficial improvement.

As the examples have shown, no success is "forever."

Yet it is even more difficult to abandon yesterday's success than it is to reappraise a failure.

A once-successful project gains an air of success that outlasts the project's real usefulness and disguises its failings.

In a service institution particularly, yesterday's success becomes "policy," "virtue," "conviction," if not holy writ.

The institution must impose on itself the discipline of thinking through its mission, its objectives, and its priorities, and of building in feedback control from results and performance on policies, priorities, and action.

Otherwise, it will gradually become less and less effective.

We are in such a welfare mess today in the United States largely because the welfare program of the 1930s was such a success.

We could not abandon it and, instead, misapplied it to the radically different problem of the inner-city poor.

To make service institutions perform, it should by now be clear, does not require great leaders.

It requires a system.

The essentials of this system are not too different from the essentials of performance in a business enterprise, but the application will be quite different.

The service institutions are not businesses; performance means something quite different in them.

The applications of the essentials differ greatly for different service institutions.

As our later examples will show, there are at least three different kinds of service institutions—institutions that are not paid for performance and results, but for efforts and programs.

How to guarantee non-performance How to guarantee non-performance

Management by Objectives — a user’s guide Management by Objectives — a user’s guide

Entrepreneurship in the Public-Service Institution

From Chapter 16 of Management, Revised Edition

Public-service institutions—such as government agencies, labor unions, churches, universities and schools, hospitals, community and charitable organizations, professional and trade associations, and the like—need to be entrepreneurial and innovative fully as much as any business does.

Indeed, they may need it more.

The rapid changes in today’s society, technology, and economy are simultaneously an even greater threat to them and an even greater opportunity.

Yet public-service institutions find it far more difficult to innovate than does even the most “bureaucratic” company.

The “existing” seems to be even more of an obstacle for them.

To be sure, every service institution likes to get bigger.

In the absence of a profit test, size is the one criterion of success for a service institution, and growth a goal in itself.

And then, of course, there is always so much more that needs to be done.

But stopping what has “always been done” and doing something new are equally anathema to service institutions, or at least excruciatingly painful to them.

Most innovations in public-service institutions are imposed on them either by outsiders or by catastrophe.

The modern university, for instance, was created by a total outsider, the Prussian diplomat Wilhelm von Humboldt.

He founded the University of Berlin in 1809, when the traditional university of the seventeenth and eighteenth century had been all but completely destroyed by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars.

Sixty years later, the modern American university came into being, when the country’s traditional colleges and universities were dying and could no longer attract students.

Similarly, all basic innovations in the military in the twentieth century, whether in structure or in strategy, have followed on ignominious malfunction or crushing defeat:

the reorganization of the American army and of its strategy by a New York lawyer, Elihu Root, Teddy Roosevelt’s secretary of war, after its disgraceful performance in the Spanish-American War;

the reorganization, a few years later, of the British army and its strategy by Secretary of War Lord Haldane, another civilian, after the equally disgraceful performance of the British in the Boer War; and

the rethinking of the German army’s structure and strategy after the defeat of World War I.

And in government, one of the greatest examples of innovative thinking in recent political history, America’s New Deal of 1933-1936, was triggered by a Depression so severe as to almost unravel the country’s social fabric.

Critics of bureaucracy blame the resistance of public-service institutions to entrepreneurship and innovation on “timid bureaucrats,” on time-servers who “have never met a payroll,” or on “power-hungry politicians.”

It is a very old litany—in fact, it was already hoary when Machiavelli chanted it almost 500 years ago.

The only thing that changes is who intones it.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, it was the slogan of the so-called liberals and now it is the slogan of the so-called neoconservatives.

Alas, things are not that simple, and “better people” that perennial panacea of reformists—is a mirage.

The most entrepreneurial, innovative people behave like the worst time-serving bureaucrat or power-hungry politician six months after they have taken over the management of a public-service institution, particularly if it is a government agency.

The forces that impede entrepreneurship and innovation in a public-service institution are inherent in it, integral to it, inseparable from it.

The best proof of this are the internal staff services in businesses, which are, in effect, the “public-service institutions” within business corporations.

These are typically headed by people who have come out of operations and have proven their capacity to perform in competitive markets.

And yet, the internal staff services are not notorious as innovators.

They are good at building empires—and they always want to do more of the same.

They resist abandoning anything they are doing.

But they rarely innovate once they have been established.

There are three main reasons why the existing enterprise presents so much more of an obstacle to innovation in the public-service institution than it does in the typical business enterprise.

First, the public-service institution is based on a “budget” rather than on being paid out of its results.

It is paid for its efforts and out of funds somebody else has earned, whether the taxpayer, the donors of a charitable organization, or the company for which a human resource department or the marketing services staff work.

The more efforts the public-service institution engages in, the greater its budget will be.

And “success” in the public-service institution is defined by getting a larger budget rather than obtaining results.

Any attempt to slough off activities and efforts, therefore, diminishes the public-service institution.

It causes it to lose stature and prestige.

Failure cannot be acknowledged.

Worse still, the fact that an objective has been attained cannot be admitted.

A service institution is dependent on a multitude of constituents.

In a business that sells its products on the market, one constituent, the consumer, eventually overrides all the others.

A business needs only a very small share of a small market to be successful.

Then it can satisfy the other constituents, whether they are shareholders, workers, the community, and so on.

But precisely because public-service institutions—and that includes the staff activities within a business corporation—have no “results” out of which they are being paid, any constituent, no matter how marginal, has, in effect, a veto power.

A public-service institution has to satisfy everyone; certainly, it cannot afford to alienate anyone.

The moment a service institution starts an activity, it acquires a “constituency,” which then refuses to have the program abolished or even significantly modified.

But anything new is always controversial.

This means that it is opposed by existing constituencies without having formed, as yet, a constituency of its own to support it.

The most important reason, however, is that public-service institutions exist, after all, to “do good.”

This means that they tend to see their mission as a moral absolute rather than as economic and subject to a cost-benefit calculus.

Economics always seeks a different allocation of the same resources to obtain a higher yield.

Everything economic is therefore relative.

In the public-service institution, there is no such thing as a higher yield.

If one is “doing good,” then there is no “better.”

Indeed, failure to attain objectives in the quest for a “good” only means that efforts need to be redoubled.

The forces of evil must be far more powerful than expected and need to be fought even harder.

For thousands of years the preachers of all sorts of religions have held forth against the “sins of the flesh.”

Their success has been limited to say the least.

But this is no argument as far as the preachers are concerned.

It does not persuade them to devote their considerable talents to pursuits in which results may be more easily attainable.

On the contrary, it only proves that their efforts need to be redoubled.

Avoiding the “sins of the flesh” is clearly a “moral good,” and thus an absolute, which does not admit to any cost-benefit calculation.

Few public-service institutions define their objectives in such absolute terms.

But even company human resource departments and manufacturing service staffs tend to see their mission as “doing good,” and therefore as being moral and absolute instead of being economic and relative.

This means that public-service institutions are out to maximize rather than to optimize.

“Our mission will not be completed,” asserts the head of the Crusade Against Hunger, “as long as there is one child on the earth going to bed hungry.”

If he were to say, “Our mission will be completed if the largest possible number of children that can be reached through existing distribution channels get enough to eat not to be stunted,” he would be booted out of office.

But if the goal is maximization, it can never be attained.

Indeed, the closer one comes to attaining one’s objective, the more efforts are called for.

For, once optimization has been reached (perhaps between 75 and 80 percent of theoretical maximum), additional costs go up exponentially while additional results fall off exponentially.

The closer a public-service institution comes to attaining its objectives, therefore, the more frustrated it will be and the harder it will work on what it is already doing.

It will, however, behave exactly the same way the less it achieves.

Whether it succeeds or fails, the demand to innovate and to do something else will be resented as an attack on its basic commitment, on the very reason for its existence, and on its beliefs and values.

The Need to Innovate

Why is innovation in the public-service institution so important?

Why can we not leave existing public-service institutions the way they are and depend on new institutions for the innovations we need in the public-service sector, as historically we have always done?

The answer is that public-service institutions have become too important in developed countries, and too big.

The public-service sector, both the governmental one and the nongovernmental but not-for-profit one, has grown faster during the twentieth century than the private sector—maybe three to five times as fast.

The growth has been especially fast since World War II.

To some extent, this growth has been excessive.

Wherever public-service activities can be converted into profit-making enterprises, they should be so converted.

This applies to not only the kind of municipal services the city of Lincoln, Nebraska, now privatizes.

The move from nonprofit to profit has already gone very far in the American hospital.

It may become a stampede in professional and graduate education.

To subsidize the highest earners in developed society—the holders of advanced professional degrees—can hardly be justified.

A central economic problem of developed societies is capital formation.

We therefore can ill afford to have activities conducted as “nonprofit”—that is, as activities that devour capital rather than form it—if they can be organized as activities that form capital, as activities that make a profit.

But the great bulk of the activities that are being discharged in and by public-service institutions will still remain public-service activities, and will neither disappear nor be transformed.

Consequently, they have to be made producing and productive.

Public-service institutions will have to learn to be innovators, to manage themselves entrepreneurially.

To achieve this, public-service institutions will have to learn to look upon social, technological, economic, and demographic shifts as opportunities in a period of rapid change in all these areas.

Otherwise, they will become obstacles.

Such public-service institutions will increasingly become unable to discharge their mission as they adhere to programs and projects that cannot work in a changed environment, and yet they will not be able or willing to abandon the missions they can no longer discharge.

Increasingly, they will come to look the way the feudal barons came to look after they had lost all social function around 1300:

as parasites, functionless, with nothing left but the power to obstruct and to exploit.

They will become self-righteous while increasingly losing their legitimacy.

Clearly, this is already happening to the apparently most powerful among them, the labor union.

Yet a society in rapid change, with new challenges, new requirements and opportunities, needs public-service institutions.

The public school in the United States exemplifies both the opportunities and the dangers.

Unless it takes the lead in innovation, it is unlikely to survive, except as a school for the minorities in the slums as parents of middle- and high-income families send their children to private and parochial schools.

For the first time in its history, the United States faces the threat of a class structure in education in which all but the very poor remain outside of the public school system—at least in the cities and suburbs where most of the population lives.

And this will squarely be the fault of the public school itself, because what is needed to reform the public school is already known.

Many other public-service institutions face a similar situation.

The knowledge is there.

The need to innovate is clear.

They now have to learn how to build entrepreneurship and innovation into their own system.

Otherwise, they will find themselves superseded by outsiders who will create competing entrepreneurial public-service institutions and so render the existing ones obsolete.

The late nineteenth century and early twentieth century was a period of tremendous creativity and innovation in the public-service field.

Social innovation during the seventy-five years until the 1930s was surely as much alive, as productive, and as rapid as technological innovation, if not more so.

But in these periods the innovation took the form of creating new public-service institutions.

The need for social innovation may be even greater now, but it will very largely have to be social innovation within the existing public-service institution.

To build entrepreneurial management into the existing public-service institution may thus be the foremost political task of this generation.

What are the consequences of non-performance? Do we (as society) have to pay someone else to perform or do we just do without? What about the executives and employees? Are they just wasting their lives?

Management as the Alternative to Tyranny

The alternative to autonomous institutions that function and perform is not freedom. It is totalitarian tyranny.

If the institutions of our pluralist society of institutions do not perform in responsible autonomy, we will not have individualism and a society in which there is a chance for people to fulfill themselves.

We will, instead, impose on ourselves complete regimentation in which no one will be allowed autonomy.

We will have Stalinism rather than participatory democracy, let alone the joyful spontaneity of doing one's own thing.

Tyranny is the only alternative to strong, performing autonomous institutions.

Tyranny substitutes one absolute boss for the pluralism of competing institutions.

It substitutes terror for responsibility.

It does indeed do away with the institutions, but only by submerging all of them in the one all embracing bureaucracy of the apparat.

It does produce goods and services, though only fitfully, wastefully, at a low level, and at an enormous cost in suffering, humiliation, and frustration.

To make our institutions perform responsibly, autonomously, and on a high level of achievement is thus the only safeguard of freedom and dignity in the pluralist society of institutions.

Performing, responsible management is the alternative to tyranny and our only protection against it.

January 10 — The Daily Drucker

Management By Objectives And Self-Control

Calendarize this?

From chapter 8 of The Essential Drucker

Amazon Link: The Essential Drucker

Any business enterprise must build a true team and weld individual efforts into a common effort.

From chapter 25 of Management, Revised Edition

Amazon Links: Management Rev Ed and Management Cases, Revised Edition and Management Cases, Revised Edition

See contents of Management Cases, Revised Edition

Each member of the enterprise contributes something different, but all must contribute toward a common goal.

Their efforts must all pull in the same direction, and their contributions must fit together to produce a whole—without gaps, without friction, without unnecessary duplication of effort.

Every job in the company must be directed toward the objectives of the whole organization if the overall goals are to be achieved.

In particular, each manager's job must be focused on the success of the whole.

The performance that is expected of managers must be directed toward the performance goals of the business.

Results are measured by the contribution they make to the success of the enterprise.

Managers must know and understand what the business goals demand of them in terms of performance, and their superiors must know what contribution to demand and expect.

If these requirements are not met, managers are misdirected and their efforts are wasted.

Management by objectives requires major effort and special techniques.

In a business enterprise managers are not automatically directed toward a common goal.

On the contrary, organization, by its very nature, contains four factors that tend to misdirect:

the specialized work of most managers the specialized work of most managers

the hierarchical structure of management the hierarchical structure of management

the differences in vision and work and the resultant isolation of various levels of management the differences in vision and work and the resultant isolation of various levels of management

the compensation structure of the management group the compensation structure of the management group

To overcome these obstacles requires more than good intentions.

It requires policy and structure.

It requires that management by objectives be purposefully organized and be made the living law of the entire management group.

The Specialized Work Of Managers

An old story tells of three stonecutters who were asked what they were doing.

The first replied, "I am making a living."

The second kept on hammering while he said, "I am doing the best job of stone-cutting in the entire country."

The third one looked up with a visionary gleam in his eyes and said, "I am building a cathedral."

The third man is, of course, the true manager.

The first man knows what he wants to get out of the work and manages to do so.

He is likely to give a "fair day's work for a fair day's pay."

But he is not a manager and will never be one.

It is the second man who is the problem.

Workmanship is essential—an organization demoralizes if it does not demand of its members the highest workmanship they are capable of.

But there is always a danger that the true workman, the true professional, will believe that he is accomplishing something when, in effect, he is just polishing stones or collecting footnotes.

Workmanship must be encouraged in the business enterprise.

But it must always be related to the needs of the whole.

Most managers and career professionals in any business enterprise are, like the second man, concerned with specialized work.

A person's habits as a manager, his vision and values, are usually formed while he does functional and specialized work.

It is essential that the functional specialist develop high standards of workmanship, that he strive to be "the best stonecutter in the country."

For work without high standards is dishonest; it corrupts the worker and those around him.

Emphasis on, and drive for, workmanship produces innovations and advances in every area of management.

That managers strive to do the best job possible—to do "professional human resource management," to run "the most up-to-date plant," to do "truly scientific market research" must be encouraged.

But this striving for professional workmanship in functional and specialized work is also a danger.

It tends to divert the manager's vision and efforts from the goals of the business.

The functional work becomes an end in itself.

In far too many instances the functional managers no longer measure their performance by its contribution to the enterprise but only by professional criteria of workmanship.

They tend to appraise subordinates by their craftsmanship and to reward and to promote them accordingly.

They resent demands made for the sake of organizational performance as interference with "good engineering," "smooth production," or "hard-hitting selling."

The functional manager's legitimate desire for workmanship can become a force that tears the enterprise apart and converts it into a loose association of working groups.

Each group is concerned only with its own craft.

Each jealously guards its own "secrets."

Each is bent on enlarging its own domain rather than on building the business.

The remedy is to counterbalance the concern for craftsmanship with concern for the common goal of the enterprise.

Focus on Contribution

Amazon link: The Daily Drucker: 366 Days of Insight and Motivation for Getting the Right Things Done

The question "What should I contribute?" gives freedom because it gives responsibility.

The great majority of executives tend to focus downward.

They are occupied with efforts rather than with results.

They worry over what the organization and their superiors "owe" them and should do for them.

And they are conscious above all of the authority they "should have."

As a result, they render themselves ineffectual.

The effective executive focuses on contribution.

He looks up from his work and outward toward goals.

He asks: "What can I contribute that will significantly affect the performance and the results of the institution I serve?"

His stress is on responsibility.

The focus on contribution is the key to effectiveness:

in a person's own work—its content, its level, its standards, and its impacts; in a person's own work—its content, its level, its standards, and its impacts;

in his relations with others—his superiors, his associates, his subordinates; in his relations with others—his superiors, his associates, his subordinates;

in his use of the tools of the executive such as meetings or reports. in his use of the tools of the executive such as meetings or reports.

The focus on contribution turns the executive's attention away from his own specialty, his own narrow skills, his own department, and toward the performance of the whole.

It turns his attention to the outside, the only place where there are results

September 5, The Daily Drucker

by Peter Drucker

How to Develop People

Any organization develops people; it either forms them or deforms them.

Any organization develops people; it has no choice.

It either helps them grow or it stunts them.

What do we know about developing people?

Quite a bit.

We certainly know what not to do, and those don'ts are easier to spell out than the dos.

First, one does not try to build upon people's weakness.

One can expect adults to develop manners and behavior and to learn skills and knowledge.

But one has to use people's personalities the way they are, not the way we would like them to be.

A second don't is to take a narrow and shortsighted view of the development of people.

One has to learn specific skills for a specific job.

But development is more than that: it has to be for a career and for a life. (calendarize this?)

The specific job must fit into this longer-term goal.

Another thing we know is not to establish crown princes.

Look always at performance, not at promise.

With the focus on performance and not potential, the executive can make high demands.

One can always relax standards, but one can never raise them.

Next, the executive must learn to place people's strengths. (See strengths in Managing Oneself)

In developing people the lesson is to focus on strengths.

Then make really stringent demands, and take the time and trouble (it's hard work) to review performance. (See "The Fourth Experience" in My Life as a Knowledge Worker)

Sit down with people and say: "This is what you and I committed ourselves to a year ago.

How have you done?

What have you done well?"

September 7, The Daily Drucker

by Peter Drucker

Harmonize the Immediate and Long-range Future

A manager must, so to speak, keep his nose to the grindstone while lifting his eyes to the hills—quite an acrobatic feat.

A manager has two specific tasks.

The first is creation of a true whole that is larger than the sum of its parts, a productive entity that turns out more than the sum of the resources put into it.

The second specific task of the manager is to harmonize in every decision and action the requirements of the immediate and of the long-range future.

A manager cannot sacrifice either without endangering the enterprise.

If a manager does not take care of the next hundred days, there will be no next hundred years.

Whatever the manager does should be sound in expediency as well as in basic long-range objective and principle.

And where he cannot harmonize the two time dimensions, he must at least balance them.

He must calculate the sacrifice he imposes on the long-range future of the enterprise to protect its immediate interests, or the sacrifice he makes today for the sake of tomorrow.

He must limit either sacrifice as much as possible.

And he must repair as soon as possible the damage it inflicts.

He lives and acts in two time dimensions, and is responsible for the performance of the whole enterprise and of his own component in it.

From Sep 28 in The Daily Drucker

originally from

Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

Creating a True Whole

Create a true whole greater than the sum of its parts.

A manager has the task of creating a true whole that is larger than the sum of its parts.

One analogy is the task of the conductor of a symphony orchestra, through whose effort, vision, and leadership individual instrumental parts become the living whole of a musical performance.

But the conductor has the composer's score; he is only interpreter.

The manager is both composer and conductor.

The task of creating a genuine whole also requires that the manager, in every one of her acts, consider simultaneously the performance and results of the enterprise as a whole and the diverse activities needed to achieve synchronized performance.

It is here, perhaps, that the comparison with the orchestra conductor fits best.

A conductor must always hear both the whole orchestra and, say, the second oboe.

Similarly, a manager must always consider both the overall performance of the enterprise and, say, the market research activity needed.

By raising the performance of the whole, she creates scope and challenge for market research.

By improving the performance of market research, she makes possible better overall business results.

The manager must simultaneously ask two double-barreled questions:

"What better business performance is needed and what does this require of what activities?"

And "What better performances are the activities capable of and what improvement in business results will they make possible?"

From Mar 7 in The Daily Drucker

originally from

Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

Connect to Peter Drucker Social Political Ecologist

There is one fundamental insight underlying all management science.

It is that the business enterprise is a system of the highest order: a system the parts of which are human beings contributing voluntarily of their knowledge, skill, and dedication to a joint venture.

And one thing characterizes all genuine systems, whether they be mechanical, like the control of a missile, biological like a tree, or social like the business enterprise:

it is interdependence.

The whole of a system is not necessarily improved if one particular function or part is improved or made more efficient.

In fact, the system may well be damaged thereby, or even destroyed.

In some cases the best way to strengthen the system may be to weaken a part—to make it less precise or less efficient.

For what matters in any system is the performance of the whole; this is the result of growth and of dynamic balance, adjustment, and integration rather than of mere technical efficiency

Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

Connect to Peter Drucker Social Political Ecologist

Making human resources productive

… There is as a consequence only one satisfactory definition of management, whether we talk of a business, a government agency, or a nonprofit organization: to make human resources productive. (the contents of this book spread over decades through several stages of development)

It will increasingly be the only way to gain competitive advantage.

Of the traditional resources of the economist—land, labor, and capital—none anymore truly confers a competitive advantage.

To be sure, not to be able to use these resources as well as anyone else is a tremendous competitive disadvantage.

But every business has access to the same raw materials at the same price.

Access to money is worldwide.

And manual labor, the traditional third resource, has become a relatively unimportant factor in most enterprises.

Even in traditional manufacturing industries, labor costs are no more than 12 or 13 percent of total costs, so that even a very substantial advantage in labor costs (say a 5 percent advantage) results in a negligible competitive advantage except in a very small and shrinking number of highly labor-intensive industries (e.g., knitting woolen sweaters).

The only meaningful competitive advantage is the productivity of the knowledge worker.

And that is very largely in the hands of the knowledge worker rather than in the hands of management.

Knowledge workers will increasingly determine the shape of the successful employing organizations.

Read more …

Preface to Management, Revised Edition

Managerial Skills, Managerial Tasks, And Personal Skills

The corporation of tomorrow will be far more complex than that of today.

It will constitute a web of partnerships, joint ventures, alliances, outsourcing contractors, and various other kinds of associates or affiliates that is unprecedented in the current breadth and intricacy.

Each aspect of the corporation may have its own management, but the relationships among entities will certainly have to be coordinated and made to perform.

This complexity requires of the manager advanced skills and practices, both in his or her role as manager and as individual professional.

Management, Revised Edition

Citizenship Through the Social Sector

Social needs will grow in two areas.

They will grow, first, in what has traditionally been considered charity: helping the poor, the disabled, the helpless, the victims.

And they will grow, perhaps even faster, in respect to services that aim at changing the community and at changing people.

In a transition period, the number of people in need always grows.

There are the huge masses of refugees all over the globe, victims of war and social upheaval, of racial, ethnic, political, and religious persecution, of government incompetence and of government cruelty.

Even in the most settled and stable societies people will be left behind in the shift to knowledge work.

It takes a generation or two before a society and its population catch up with radical changes in the composition of the work force and in the demands for skills and knowledge.

It takes some time—the best part of a generation, judging by historical experience—before the productivity of service workers can be raised sufficiently to provide them with a "middle-class" standard of living.

The needs will grow equally—perhaps even faster—in the second area of social services, services which do not dispense charity but attempt to make a difference in the community and to change people.

Such services were practically unknown in earlier times, whereas charity has been with us for millennia.

But they have mushroomed in the last hundred years, especially in the United States.

These services will be needed even more urgently in the next decades.

One reason is the rapid increase in the number of elderly people in all developed countries, most of whom live alone and want to live alone.

A second reason is the growing sophistication of health care and medical care, calling for health care research, health care education, and for more and more medical and hospital facilities.

Then there is the growing need for continuing education of adults, and the need created by the growing number of one-parent families.

The community service sector is likely to be one of the true "growth sectors" of developed economies, whereas we can hope that the need for charity will eventually subside again.

Post-Capitalist Society

Handbook For The Positive Revolution

Edward de Bono

Career / life vision guidance from Peter Drucker — extremely, extremely, extremely valuable attention-directing concepts and ideas from a long-term standpoint.

Knowledge workers face significant new demands.

They have to ask, "Who am I? What are my strengths? How do I work?" (calendarize this?)

They have to ask, "Where do I belong?" (calendarize this?)

They have to ask, "What is my contribution?" (calendarize this?)

They have to take responsibility for their relationships, up and down and sideways. (calendarize this?)

If one were to take a poll, it is likely that few people would identify themselves as ever having considered topics such as:

Am I a listener or reader? (calendarize this?)

How do I learn most effectively? (calendarize this?)

Is my job aligned with my values? (calendarize this?)

What is my plan for continuous learning and self-revitalization? (calendarize this?)

What is my plan for the second half of my life? (calendarize this?)

What do I want to be remembered for? (calendarize this?)

Management, Revised Edition

Managing Oneself is the place to start and the foundation for everything else — it sets the right example (calendarize this?)

Additional building blocks for creating real TLN capacity

Larger view

Changing Social and Economic Picture

Economic Content and Structure

Organization Evolution

Concepts to Daily Action

Drucker Essay Collections

Although written years ago, these essays can be valuable attention directing tools. They can take your brain to places (brain addresses and brain roads) it wouldn't naturally go. What has changed and what is likely to change?

Technology, Management and Society Technology, Management and Society

Men, Ideas & Politics Men, Ideas & Politics

Toward the Next Economics and Other Essays Toward the Next Economics and Other Essays

The Ecological Vision: Reflections on the American Condition The Ecological Vision: Reflections on the American Condition

A Functioning Society: Selections from Sixty-Five Years of Writing on Community, Society, and Polity A Functioning Society: Selections from Sixty-Five Years of Writing on Community, Society, and Polity

“Time Related” Management Books

Important ways to “see” otherwise invisible aspects of reality and to relocate one's brain to unfamiliar territory.

Some of the chapter topics have made their way into The Daily Drucker

The subtopics below selected book titles are not the entire contents that book.

Managing in Turbulent Times Managing in Turbulent Times

Toward the Next Economics and Other Essays Toward the Next Economics and Other Essays

The Changing World of The Executive The Changing World of The Executive

A Scorecard for Management A Scorecard for Management

… “bottom line” is not even an appropriate measure of management performance

Performance in Appropriating Capital Performance in Appropriating Capital

Performance on People Decisions Performance on People Decisions

Innovation Performance Innovation Performance

Planning Performance (reality vs. expectations) Planning Performance (reality vs. expectations)

Learning From Foreign Management Learning From Foreign Management

Demand responsibility from their employees Demand responsibility from their employees

Thought through their benefits policies more carefully Thought through their benefits policies more carefully

Take marketing seriously — knowing what is value for the customer Take marketing seriously — knowing what is value for the customer

Base their marketing and innovation strategies on the systematic and purposeful abandonment Base their marketing and innovation strategies on the systematic and purposeful abandonment

Longer-term investment or opportunities budgets Longer-term investment or opportunities budgets

Leaders responsible for the development of proper policies in the national interest Leaders responsible for the development of proper policies in the national interest

Aftermath of a Go-Go Decade Aftermath of a Go-Go Decade

Managing Capital Productivity Managing Capital Productivity

Measuring Business Performance Measuring Business Performance

Performance in a business means applying capital productively and there is only one appropriate yardstick of business performance: return on all assets employed or on all capital invested

Good Growth and Bad Growth Good Growth and Bad Growth

Managing the Knowledge Worker Managing the Knowledge Worker

Frontiers of Management Frontiers of Management

Measuring White Collar Productivity Measuring White Collar Productivity

Getting Control of Staff Work Getting Control of Staff Work

Slimming Management’s Midriff Slimming Management’s Midriff

The No-Growth Enterprise The No-Growth Enterprise

Why Automation Pays Off Why Automation Pays Off

Managing for the Future Managing for the Future

The New Productivity Challenge The New Productivity Challenge

Manage by walking around — Outside! Manage by walking around — Outside!

Permanent cost cutting: permanent policy Permanent cost cutting: permanent policy

Four marketing lessons for the future Four marketing lessons for the future

Company performance: five telltale tests Company performance: five telltale tests

Market standing Market standing

Innovative performance Innovative performance

Productivity Productivity

Liquidity and Cash Flows Liquidity and Cash Flows

Profitability Profitability

No Precise Readings No Precise Readings

The trend toward alliances for progress The trend toward alliances for progress

The emerging theory of manufacturing The emerging theory of manufacturing

Sell the Mailroom. Unbundling in the ‘90s Sell the Mailroom. Unbundling in the ‘90s

Managing in a Time of Great Change Managing in a Time of Great Change

The theory of the business The theory of the business

Planning for uncertainty Planning for uncertainty

The five deadly business sins The five deadly business sins

Management Challenges for the 21st Century Management Challenges for the 21st Century