Druckerisms — (calendarize this?)

“The customer never buys what you think you sell. And you don’t know it. That’s why it’s so difficult to differentiate yourself.”

“The customer never buys what you think you sell. And you don’t know it. That’s why it’s so difficult to differentiate yourself.”

“Economists never know anything until twenty years later. There are no slower learners than economists. There is no greater obstacle to learning than to be the prisoner of totally invalid but dogmatic theories. The economists are where the theologians were in 1300: prematurely dogmatic” — Frontiers of Management

Follow effective action with quiet reflection. From the quiet reflection will come even more effective action.

Follow effective action with quiet reflection. From the quiet reflection will come even more effective action.

Knowledge has to be improved, challenged, and increased constantly, or it vanishes.

Knowledge has to be improved, challenged, and increased constantly, or it vanishes.

The really important things are said over cocktails and are never done. (calendarize this?)

Management by objective works – if you know the objectives. Ninety percent of the time you don’t.

Management by objective works – if you know the objectives. Ninety percent of the time you don’t.

Objectives are not fate; they are direction. They are not commands; they are commitments. They do not determine the future; they are means to mobilize the resources and energies of the business for the making of the future.

Objectives are not fate; they are direction. They are not commands; they are commitments. They do not determine the future; they are means to mobilize the resources and energies of the business for the making of the future.

Most discussions of decision-making assume that only senior executives make decisions or that only senior executives decisions matter. This is a dangerous mistake.

Most discussions of decision-making assume that only senior executives make decisions or that only senior executives decisions matter. This is a dangerous mistake.

People who don’t take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year. People who do take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year.

People who don’t take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year. People who do take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year.

That people even in well paid jobs choose ever earlier retirement is a severe indictment of our organizations — not just business, but government service, the universities. These people don’t find their jobs interesting. (calendarize this?)

That people even in well paid jobs choose ever earlier retirement is a severe indictment of our organizations — not just business, but government service, the universities. These people don’t find their jobs interesting. (calendarize this?)

Few top executives can even imagine the hatred, contempt and fury that has been created — not primarily among blue-collar workers who never had an exalted opinion of the ‘bosses’ — but among their middle management and professional people. What do you want to be remembered for?

Few top executives can even imagine the hatred, contempt and fury that has been created — not primarily among blue-collar workers who never had an exalted opinion of the ‘bosses’ — but among their middle management and professional people. What do you want to be remembered for?

The individual is the central, rarest, most precious capital resource of our society.

The individual is the central, rarest, most precious capital resource of our society.

The subordinate’s job is not to reform or re-educate the boss, not to make him conform to what the business schools or the management book say bosses should be like. It is to enable a particular boss to perform as a unique individual. (To calendarize this see chapter 46 in Management, Revised Edition)

Topics from A Class With Drucker to consider calendarizing:

What Everybody Knows Is Frequently Wrong

What Everybody Knows Is Frequently Wrong

If You Keep Doing What Worked in the Past You’re Going to Fail

If You Keep Doing What Worked in the Past You’re Going to Fail

Approach Problems with Your Ignorance—Not Your Experience

Approach Problems with Your Ignorance—Not Your Experience

Develop Expertise Outside Your Field to Be an Effective Manager

Develop Expertise Outside Your Field to Be an Effective Manager

Outstanding Performance Is Inconsistent with Fear of Failure

Outstanding Performance Is Inconsistent with Fear of Failure

You Must Know Your People to Lead Them

You Must Know Your People to Lead Them

People Have No Limits, Even After Failure

People Have No Limits, Even After Failure

Base Your Strategy on the Situation, Not on a Formula

Base Your Strategy on the Situation, Not on a Formula

One of the advantages of openly using Drucker's work (as attention-directing tools) is that it sets the right example. This may lead to others doing the same thing and then others doing the same thing …

Bob Buford's work provides a second-half of your life landscape exploration.

The work of quite a few other “thought leaders” is also available for comparison shopping and mental landscape breadth — a vital necessity.

Preparing for a different world and different future through time investing is this site's function and reason for existence. It offers an extensive menu and a shopping mall of concepts — these are not tips, they are alternative roads to travel.

There are over 500 web pages designed for a variety of individuals in various situations and life stages. They are all aimed at moving forward and not becoming a prisoner of the past. They are brainroads and brainscapes for conceiving effective action.

As a CEO you have to be concerned with this both for yourself and everybody in your network over time. If the members of your network are prisoners of yesterday then so are you. (calendarize this?)

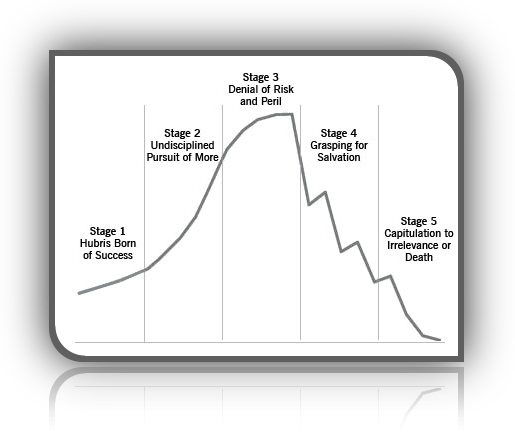

I'm guessing that CEOs in 1950, 1970, or 1990 ... believed they had things under control. History has proven they had the wrong things on their radar and were spending their time on the wrong things. Whatever lead time they had — before the crisis that was their undoing — was wasted on the wrong things. Part of this situation involves being blinded by the familiar. Any organization, institution, or enterprise is composed of both an “idea” and the activities that implement the idea. Since people enter the workforce through the activities doorway that's all they see and its all the experience they have. It is almost inconceivable that a new and different “idea” or basic concept is needed. (calendarize this?)

… By now everybody at General Motors knows that these are the crucial problems. And yet General Motors does not seem able to resolve them. Instead General Motors has tried to sidestep them by the old — and always unsuccessful — attempt to “diversify.” Acting on the oldest delusion of managements: “if you can’t run your own business buy one of which you know nothing,” General Motors has bought first Electronic Data Systems and then Hughes Aircraft. Predictably this will not solve General Motors’s problems. Only becoming again a truly effective automobile manufacturer can do that. — The Concept of the Corporation

Almost nobody is prepared for the roadS ahead of us — it involves new basic concepts. Very, very few have even been exposed to this material. Even fewer have done anything about it — the evidence is all around us. (calendarize this?)

Spencer Stuart’s Tom Neff, the dean of CEO Executive Search, puts it baldly: “We are experiencing a demand for new types of skills and sacrifices in C-level executives that many are not prepared to bring to the table.” (Quote Source) Connections: see related comments on “M.B.A. programs” and then further down the page “learning and teaching institution”.

You are most likely surrounded by people who are working with yesterday’s brain and who subconsciously assume that the 1970s … are coming back — a world where filling a vacuum was sufficient. The vacuums are basically gone.

The roads that individuals and organizations travel don’t run in parallel any more.

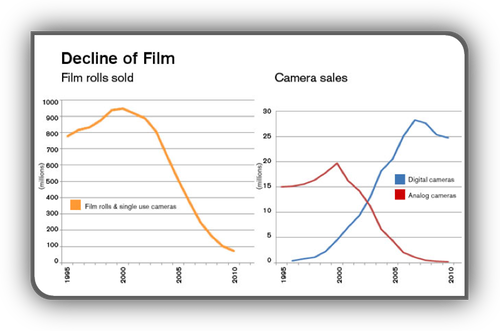

Larger

Years ago I was a Fortune 200 corporate restructurer. Nobody sees it coming—even when its in plain sight. For some strange reasons we humans can’t seem to do the “effective thing” soon enough. Yesterdays almost always seem to trump tomorrows — with severe consequences. The beliefs that nothing bad can happen and that tomorrows will look just like today is a global mental disease — without any evidence to support these beliefs. The only time that I've seen a mental breakthrough is when someone is told to clean out their desk. If CEOs don't change these attitudes nobody else will. The future health of our world depends on this.

The End of Economic Man: The Origins of Totalitarianism

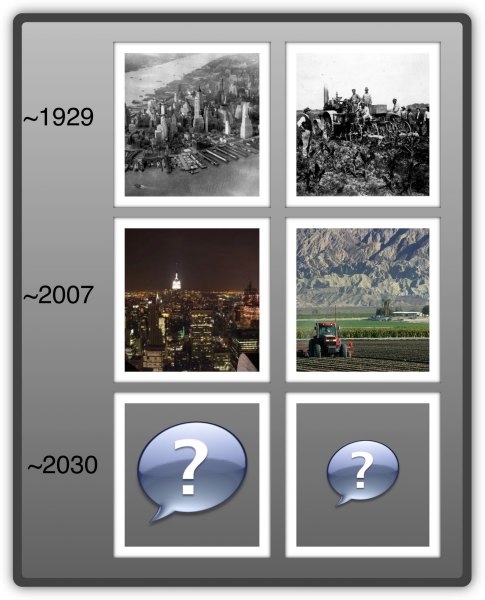

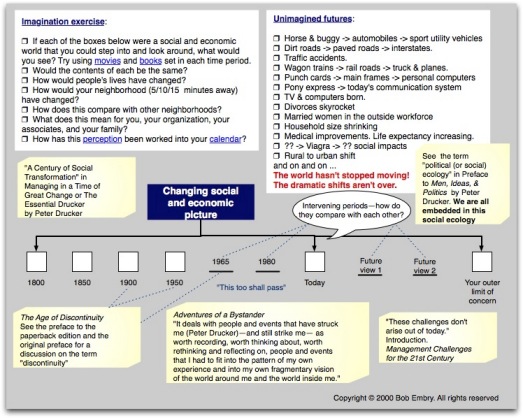

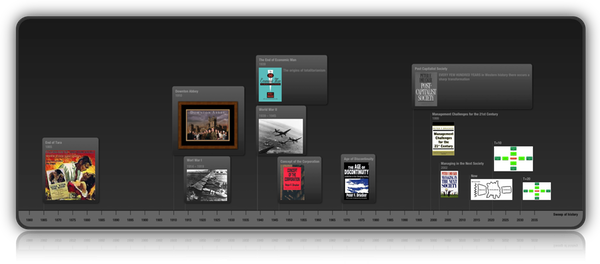

THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE: Think about movies from different eras. Do they portray the same external situations (time and place) or a world moving toward unimagined futures?

THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE: Think about movies from different eras. Do they portray the same external situations (time and place) or a world moving toward unimagined futures?

The world is moving away from pre-industrial conditions and the movement is not linear. A tweet is not a linear extrapolation of a telegraph. A smart phone is not a linear extrapolation of a black rotary phone of the 1950s. Industry composition and structures are not static. Apple ™ today is not a linear extrapolation of two guys working out of a garage.

A Century of Social Transformation—Emergence of Knowledge Society

The Changing Social and Economic Picture

The End of Economic Man: The Origins of Totalitarianism (1939)

The Future of Industrial Man (1943)

The New Society: The Anatomy of Industrial Order (1950)

Landmarks of Tomorrow (1957)

The Age of Discontinuity (1968)

The New Realities (1988)

Post-Capitalist Society (1993)

Managing in the Next Society (2002);

Last section originally published earlier in The Economist

Sweep of History

Post capitalist transformation

The productivity of knowledge is going to be the determining factor in the competitive position of a company, an industry, an entire country.

No country, industry, or company has any “natural” advantage or disadvantage.

The only advantage it can possess is the ability to exploit universally available knowledge.

The only thing that increasingly will matter in national as in international economics is management's performance in making knowledge productive. — Knowledge: its economics and productivity

Knowledge workers will increasingly determine the shape of the successful employing organizations. — Management, Revised Edition !!!

Knowledge society , a society of organizations, management

The 90/10 Rule at Yum! Brands

But every analysis of actual allocation of resources and efforts in business that I have ever seen or made showed clearly that the bulk of time, work, attention, and money first goes to 'problems' rather than to opportunities, and, secondly, to areas where even extraordinarily successful performance will have minimal impact on results. (calendarize this?)

One of the hardest things for a manager to remember is that of the 1,000 different situations he or she will be asked to deal with on any given day, only the smallest handful have a shot at moving the enterprise forward in a truly significant way (calendarize this?)

The job of management, then, is to make sure that financial capital, technology, and top talent are deployed where most of the results are and where most of the costs aren't. The temptation often exists, however, to do exactly the opposite

High tech is living in the nineteenth century, the pre-management world. They believe that people pay for technology. They have a romance with technology. But people don't pay for technology: they pay for what they get out of technology. The Frontiers of Management

Beware of people selling answers or THEIR specialized … They can't control what happens — the future. (calendarize this?)

The tools taught in M.B.A. programs fall in this group. Tools without higher level concepts and reality awareness are ineffective at best. Consider the evidence in Competing For The Future

A significant danger stems from being inside-out, product/service driven and functionally organized. The world doesn't need anymore inside-out organizations — except in the brief period of introducing a real innovation. There are too many already. (calendarize this?) Alternatives are presented below …

Also there is a tremendous amount of buzz-words floating around … that ignore realities. Lots of people trying to make a name for themselves pushing their “little” specialized answer — created in isolation from reality. They claim their answer will solve the problems of being inside-out … (calendarize this?) How does the 80/20 rule fit here? See Kodak and Sony situations — would a better tool “answer” make them healthy?

Attracting and Holding People

The first sign of decline of an industry is loss of appeal to able people.

In the area of people, genuine marketing objectives are required.

“What do our jobs have to be to attract and hold the kind of people we need and want?

What is the supply available on the job market?

And, what do we have to do to attract it?”

It is highly desirable to have specific objectives for manager supply, development, and performance, but also specific objectives for major groups within the nonmanagerial workforce.

There is need for objectives for employee attitudes as well as for employee skills.

The first sign of decline of an industry is loss of appeal to qualified, able, and ambitious people.

The American railroads, for instance, did not begin their decline after World War II—it only became obvious and irreversible then.

The decline actually set in around the time of World War I.

Before World War I, able graduates of American engineering schools looked for a railroad career.

From the end of World War I on—for whatever reason—the railroads no longer appealed to young engineering graduates, or to any educated young people.

As a result, there was nobody in management capable and competent to cope with new problems when the railroads ran into heavy weather twenty years later.

April 16 The Daily Drucker

New job thinking (calendarize this?)

New job thinking (calendarize this?)

What needs doing? and other key effectiveness ideas (calendarize this?)

What needs doing? and other key effectiveness ideas (calendarize this?)

“Leaders don’t start out asking, ‘What do I want to do?’ They ask, ‘What needs to be done?’ Then they ask, ‘Of those things that would make a difference, which are right for me?’ They don’t tackle things they aren’t good at. They make sure other necessities get done, but not by them.”

Management must also enable the enterprise and each of its members to grow and develop as needs and opportunities change.

Every enterprise is a learning and teaching institution.

Training and development must be built into it on all levels—training and development that never stop. — Chapter 2 of Management, Revised Edition (calendarize this?)

Create "Cliff notes" for important topics: Information challenges example. You can't work on things that aren't on your radar.

Peter Drucker On Leadership (the secret office)

Peter Drucker On Leadership (the secret office)

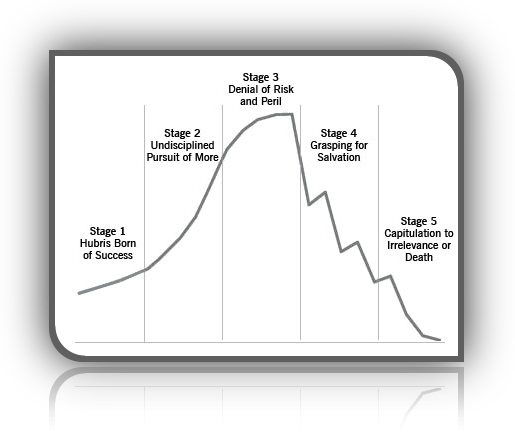

Financial results: positive financial results don't last that long … Don't relax when the numbers look good. Check out what happened to the In Search of Excellence companies. There is a complexity here that goes way beyond the intent of this page. Message: keep moving toward tomorrowS … Beware of the research methodology used to promote somebody’s “answer.” Yesterday's top performing organizations rest on different realities … See the five deadly sins, the shakeout, and Drucker on profitability below. There is a need to think in terms of real world “economics” not the world according to accountants and tax collectors. There is much mumbo-jumbo here and lots of people trying to make a monkey out of those who are naive.

Financial results: positive financial results don't last that long … Don't relax when the numbers look good. Check out what happened to the In Search of Excellence companies. There is a complexity here that goes way beyond the intent of this page. Message: keep moving toward tomorrowS … Beware of the research methodology used to promote somebody’s “answer.” Yesterday's top performing organizations rest on different realities … See the five deadly sins, the shakeout, and Drucker on profitability below. There is a need to think in terms of real world “economics” not the world according to accountants and tax collectors. There is much mumbo-jumbo here and lots of people trying to make a monkey out of those who are naive.

Think about two people working out of a garage. What do they do to become a credible participant in society?

Think about two people working out of a garage. What do they do to become a credible participant in society?

Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak

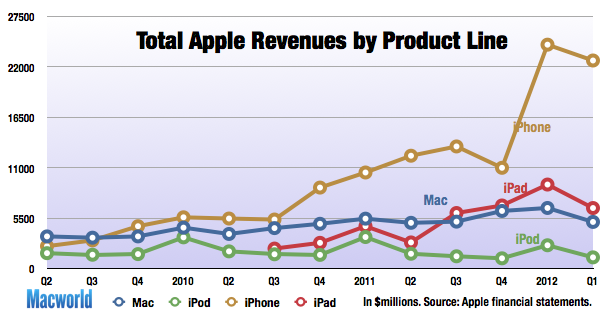

Apple: Most Admired

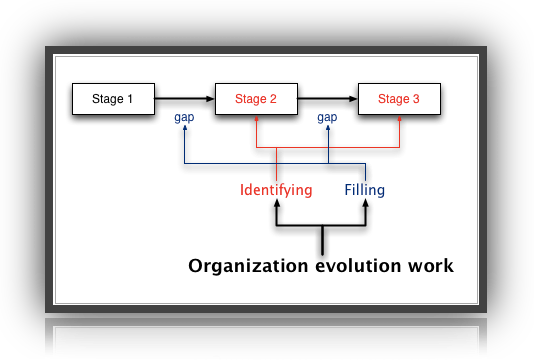

Organization evolution ©

Ten years ago who would have imagined the revenue impact of iPhones and iPads. This is an example organization evolution ©.

Think about the Kodak, RIM, Sony, and HP situations. What could they have done earlier? What about the value of their activities and efforts that failed them and lead them to the brink … their marketing, employee development, strategic planning, research and development … in other words their mismanagement and ignorance of how the world works. Living in their own little logic bubble … If there were neat and easy answers they could buy from some “expert,” why haven’t they done so? If “branding” were the answer …

Think about the Kodak, RIM, Sony, and HP situations. What could they have done earlier? What about the value of their activities and efforts that failed them and lead them to the brink … their marketing, employee development, strategic planning, research and development … in other words their mismanagement and ignorance of how the world works. Living in their own little logic bubble … If there were neat and easy answers they could buy from some “expert,” why haven’t they done so? If “branding” were the answer …

Who Says Elephants Can't Dance?: Leading a Great Enterprise (IBM) through Dramatic Change by Louis V. Gerstner, Jr.

Turnaround menu

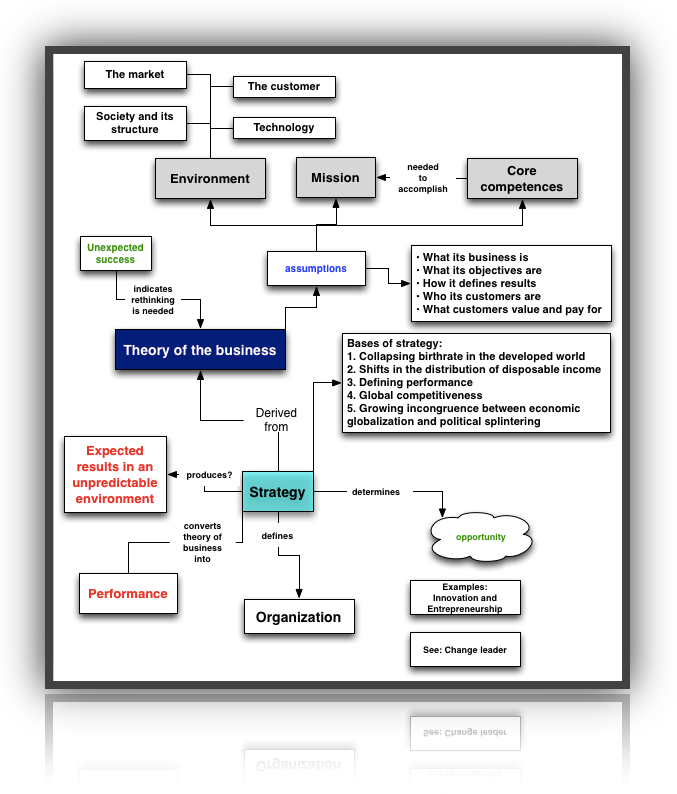

The Theory of the Business

Think about the composition of the Forbes 400. Were they thinking short-term?

Think about the composition of the Forbes 400. Were they thinking short-term?

The Truth About Wealth

Why The List (400 Wealthiest) by Steve Forbes

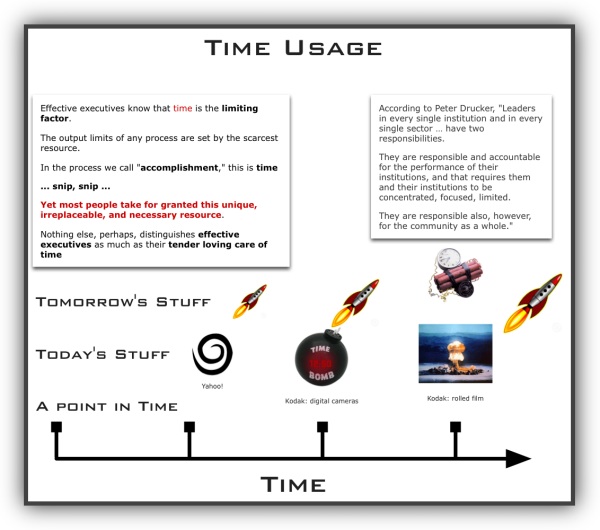

Thinking about time usage

Thinking about time usage

What do you want to be remembered for? (very important landscape to explore — more foundations for future directed decisions similar to the ones that follow on this page)

What do you want to be remembered for? (very important landscape to explore — more foundations for future directed decisions similar to the ones that follow on this page)

Defining the Duties Of the American CEO

Defining the Duties Of the American CEO

An edited version is presented in Chapter 43 “The CEO in the New Millennium” in Management, Revised Edition

An edited version is presented in Chapter 43 “The CEO in the New Millennium” in Management, Revised Edition

“The CEO in the New Millennium” — Managing in the Next Society

“The CEO in the New Millennium” — Managing in the Next Society

Managing the Nonprofit Organization

Managing the Nonprofit Organization

The Five Most Important Questions

The Five Most Important Questions

The board

The board

Management or Leadership. What's the real story?

Management or Leadership. What's the real story?

Requisites of competitive success. Is this really adequate to the challenges ahead?

Requisites of competitive success. Is this really adequate to the challenges ahead?

Five deadly business sins (calendarize this?)

Five deadly business sins (calendarize this?)

DANGER — Work- and Task-Focused Design: Functional Structure and Team (contract to social ecology) (calendarize this?)

DANGER — Work- and Task-Focused Design: Functional Structure and Team (contract to social ecology) (calendarize this?)

I've worked in over sixty organizations and I never ran across the slightest evidence that anyone had anything beyond a spark-plug's world view. Everyone was well aware of the heat and pressure. A few may have sensed they were part of an engine, but nobody realized they were part of a car going somewhere for a reason and adapted their behavior. Work on increasing specialized knowledge will not alter the world-view.

What executives should remember

What executives should remember

Toward new organizations

Toward new organizations

Management's new paradigms (calendarize this?)

Management's new paradigms (calendarize this?)

AS WE ADVANCE deeper into the knowledge economy, the basic assumptions underlying much of what is taught and practiced in the name of management are hopelessly out of date. (calendarize this?)

The principles of innovation

The principles of innovation

Chapters three through ten of Innovation and Entrepreneurship should be calendarized by someone within your organization. Part of this should include a who needs to know analysis.

Entrepreneurial strategies

Entrepreneurial strategies

The shakeout

The Definitive Drucker (lots of attention-directing questions)

The Definitive Drucker (lots of attention-directing questions)

Compare these alternative landscapes

Compare these alternative landscapes

Chaotics: The Business of Managing and Marketing in the Age of Turbulence by Philip Kotler and John A. Caslione

Chaotics: The Business of Managing and Marketing in the Age of Turbulence by Philip Kotler and John A. Caslione

Management Alert: Don't Reform—Transform! by Michael J. Kami

Management Alert: Don't Reform—Transform! by Michael J. Kami

Sur/petition by Edward de Bono

Sur/petition by Edward de Bono

Reality Check by Guy Kawasaki

Reality Check by Guy Kawasaki

Management, Revised Edition by Peter Drucker with Joseph A. Maciariello — concepts

Management, Revised Edition by Peter Drucker with Joseph A. Maciariello — concepts

The only meaningful competitive advantage is the productivity of the knowledge worker.

And that is very largely in the hands of the knowledge worker rather than in the hands of management.

Knowledge workers will increasingly determine the shape of the successful employing organizations. Read more …

Management Cases (Revised Edition) by Peter Drucker, revised and updated by Joseph A. Maciariello — situations

Management Cases (Revised Edition) by Peter Drucker, revised and updated by Joseph A. Maciariello — situations

“From Analysis to Perception — The New World View” found in The New Realities or The Essential Drucker. Form and Function Connections: see chapters On Being the Right Size and On Being the Wrong Size in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices and others. (calendarize this?)

“From Analysis to Perception — The New World View” found in The New Realities or The Essential Drucker. Form and Function Connections: see chapters On Being the Right Size and On Being the Wrong Size in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices and others. (calendarize this?)

More …

More …

Everything comes together in decisions (calendarize this?)

Everything comes together in decisions (calendarize this?)

People decisions the ultimate control of an organization. (calendarize this?)

People decisions the ultimate control of an organization. (calendarize this?)

Spending decisions. (calendarize this?)

Spending decisions. (calendarize this?)

Larger

Content of the two previous illustrations

is from Management, Revised Edition

NBC Universal's Jeff Zucker says he's being shown the door

Comcast's Steve Burke told him to 'move on' after the merger.

Jeff Zucker, a lifelong employee of NBC Universal, said Friday that he would step down as chief executive after being told there won't be a place for him once Philadelphia cable giant Comcast Corp. takes over the company at the end of the year.

Now, for the rest of the story …

Soros to return outsiders' hedge fund money

(Reuters)—Billionaire investor George Soros, whose stock-picking career has spanned nearly four decades, said he will manage money only for himself and his family as new regulations threaten to crimp the hedge fund industry he made famous.

The octogenarian fund manager, known as much for earning $1 billion on a nervy currency bet as for giving away millions to support liberal causes, will return roughly $1 billion to outside investors most likely by the end of the year and turn Soros Fund Management into a family office. The sum represents only a small portion of the $25 billion he oversees.

Keith Anderson, who has been Soros' chief investment officer since 2008, will leave the firm.

Now, for the rest of the story …

Soros hires new chief investment officer

(Reuters)—Billionaire investor George Soros is continuing to overhaul the management team of his Soros Fund Management LLC, which is converting from a hedge fund to a family office.

The octogenarian fund manager, who is in the process of returning $1 billion to outside investors, announced in a September 19 letter that Scott Bessent is joining as the firm's new chief investment officer.

Bessent, a former Soros fund alum, most recently was a senior partner and director of research for Protege Partners. He will takeover for Keith Anderson, who stepped down as the fund's chief investment officer in July.

Now, for the rest of the story …

Drucker on profits and profitability

From The Frontiers of Management

... snip, snip ...

… These days I am always being asked to explain the success of the Japanese, especially as compared with the apparent malperformance of American business in recent years.

One reason for the difference is not, as is widely believed, that the Japanese are not profit conscious or that Japanese businesses operate at a lower profit margin.

This is pure myth.

In fact, when measured against the cost of capital—the only valid measurement for the adequacy of a company's profit—large Japanese companies have, as a rule, earned more in the last ten or fifteen years than comparable American companies.

And that is the main reason the Japanese have had the funds to invest in global distribution of their products.

Also, in sharp contrast to governmental behavior in the West, Japan's government, especially the powerful Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), is constantly pushing for higher industrial profits to ensure an adequate supply of funds for investment in the future—in jobs, in research, in new products, and in market development.

One of the principal reasons for the success of Japanese business is that Japanese managers do not start out with a desired profit, that is, with a financial objective in mind.

Rather, they start out with business objectives and especially with market objectives.

They begin by asking “How much market standing (not the same as market share) do we need to have leadership?”

“What new products do we need for this?”

“How much do we need to spend to train and develop people, to build distribution, to provide the required service?”

Only then do they ask “And how much profit is necessary to accomplish these business objectives?”

Then the resulting profit requirement is usually a good deal higher than the profit goal of the Westerner.

Second, Japanese businesses—perhaps as a long-term result of my management seminars twenty and thirty years ago—have come to accept what they originally thought was very strange doctrine.

They have come to accept my position that the end of business is not “to make money.”

Making money is a necessity of survival.

It is also a result of performance and a measurement thereof.

But in itself it is not performance.

As I mentioned earlier, the purpose of a business is to create a customer and to satisfy a customer. (being outside-in rather than inside-out)

That is performance and that is what a business is being paid for.

The job and function of management as the leader, decision maker, and value setter of the organization, and, indeed, the purpose and rationale of an organization altogether, is to make human beings productive so that the skills, expectations, and beliefs of the individual lead to achievement in joint performance.

These were the things which, almost thirty years ago, Ed Deming, Joe Juran, and I tried to teach the Japanese.

Even then, every American management text preached them.

The Japanese, however, have been practicing them ever since.

I have never slighted techniques in my teaching, writing, and consulting.

Techniques are tools; without tools, there is no “practice,” only preaching.

In fact, I have designed, or at least formulated, a good many of today’s management tools, such as management by objectives, decentralization as a principle of organizational structure, and the whole concept of “business strategy,” including the classification of products and markets.

My seminars in Japan also dealt heavily with tools and techniques.

In the summer of 1985, during my most recent trip to Japan, one of the surviving members of the early seminars reminded me that the first week of the very first seminar I ran opened with a question by a Japanese participant, “What are the most useful techniques of analysis we can learn from the West?”

We then spent several days of intensive work on breakeven analysis and cash-flow analysis: two techniques that had been developed in the West in the years immediately before and after World War II, and that were still unknown in Japan.

Similarly, I have always emphasized in my writing, in my teaching, and in my consulting the importance of financial measurements and financial results.

Indeed, most businesses do not earn enough.

What they consider profits are, in effect, true costs.

One of my central theses for almost forty years has been that one cannot even speak of a profit unless one has earned the true cost of capital.

And, in most cases, the cost of capital is far higher than what businesses, especially American businesses, tend to consider as “record profits.”

I have also always maintained—often to the scandal of liberal readers—that the first social responsibility of a business is to produce an adequate surplus.

Without a surplus, it steals from the commonwealth and deprives society and the economy of the capital needed to provide jobs for tomorrow.

Further, for more years than I care to remember, I have maintained that there is no virtue in being nonprofit and that, indeed, any activity that could produce a profit and does not do so is antisocial.

Professional schools are my favorite example.

There was a time when such activities were so marginal that their being subsidized by society could be justified.

Today, they constitute such a large sector that they have to contribute to the capital formation of an economy in which capital to finance tomorrow’s jobs may well be the central economic requirement, and even a survival need.

But central to my writing, my teaching, and my consulting has been the thesis that the modern business enterprise is a human and a social organization.

Management as a discipline and as a practice deals with human and social values.

To be sure, the organization exists for an end beyond itself.

In the case of the business enterprise, the end is economic (whatever this term might mean); in the case of the hospital, it is the care of the patient and his or her recovery; in the case of the university, it is teaching, learning, and research.

To achieve these ends, the peculiar modern invention we call management organizes human beings for joint performance and creates a social organization.

But only when management succeeds in making the human resources of the organization productive is it able to attain the desired outside objectives and results.

... snip, snip ... (calendarize this?)

… Social problems, such as a deteriorating educational system, by contrast, are dysfunctions of society rather than impacts of the organization and its activities.

Since the institution can exist only within the social environment and is indeed an organ of society, such social problems affect the institution.

They are of concern to it even if … the company had no role in producing the decline in the education system.

A healthy business, a healthy university, a healthy hospital cannot exist in a sick society.

Management has a self-interest in a healthy society, even though the cause of society's sickness is not of management's making. (calendarize this?)

Management, Revised Edition

Harmonize the Immediate and Long-range Future

A manager must, so to speak, keep his nose to the grindstone while lifting his eyes to the hills—quite an acrobatic feat.

A manager has two specific tasks.

The first is creation of a true whole (just below) that is larger than the sum of its parts, a productive entity that turns out more than the sum of the resources put into it.

The second specific task of the manager is to harmonize in every decision and action the requirements of the immediate and of the long-range future.

A manager cannot sacrifice either without endangering the enterprise.

If a manager does not take care of the next hundred days, there will be no next hundred years.

Whatever the manager does should be sound in expediency as well as in basic long-range objective and principle.

And where he cannot harmonize the two time dimensions, he must at least balance them.

He must calculate the sacrifice he imposes on the long-range future of the enterprise to protect its immediate interests, or the sacrifice he makes today for the sake of tomorrow.

He must limit either sacrifice as much as possible.

And he must repair as soon as possible the damage it inflicts.

He lives and acts in two time dimensions, and is responsible for the performance of the whole enterprise and of his own component in it. (calendarize this?)

From Sep 28 in The Daily Drucker

originally from

Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

Creating a True Whole

Create a true whole greater than the sum of its parts.

A manager has the task of creating a true whole that is larger than the sum of its parts.

One analogy is the task of the conductor of a symphony orchestra, through whose effort, vision, and leadership individual instrumental parts become the living whole of a musical performance.

But the conductor has the composer's score; he is only interpreter.

The manager is both composer and conductor.

The task of creating a genuine whole also requires that the manager, in every one of her acts, consider simultaneously the performance and results of the enterprise as a whole and the diverse activities needed to achieve synchronized performance.

It is here, perhaps, that the comparison with the orchestra conductor fits best.

A conductor must always hear both the whole orchestra and, say, the second oboe.

Similarly, a manager must always consider both the overall performance of the enterprise and, say, the market research activity needed.

By raising the performance of the whole, she creates scope and challenge for market research.

By improving the performance of market research, she makes possible better overall business results.

The manager must simultaneously ask two double-barreled questions:

“What better business performance is needed and what does this require of what activities?”

And “What better performances are the activities capable of and what improvement in business results will they make possible?”

(calendarize this?)

From Mar 7 in The Daily Drucker

originally from

Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

There is one fundamental insight underlying all management science.

It is that the business enterprise is a system of the highest order: a system the parts of which are human beings contributing voluntarily of their knowledge, skill, and dedication to a joint venture.

And one thing characterizes all genuine systems, whether they be mechanical, like the control of a missile, biological like a tree, or social like the business enterprise:

it is interdependence.

The whole of a system is not necessarily improved if one particular function or part is improved or made more efficient.

In fact, the system may well be damaged thereby, or even destroyed.

In some cases the best way to strengthen the system may be to weaken a part—to make it less precise or less efficient.

For what matters in any system is the performance of the whole; this is the result of growth and of dynamic balance, adjustment, and integration rather than of mere technical efficiency

Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

An Operational View of the Budgeting Process

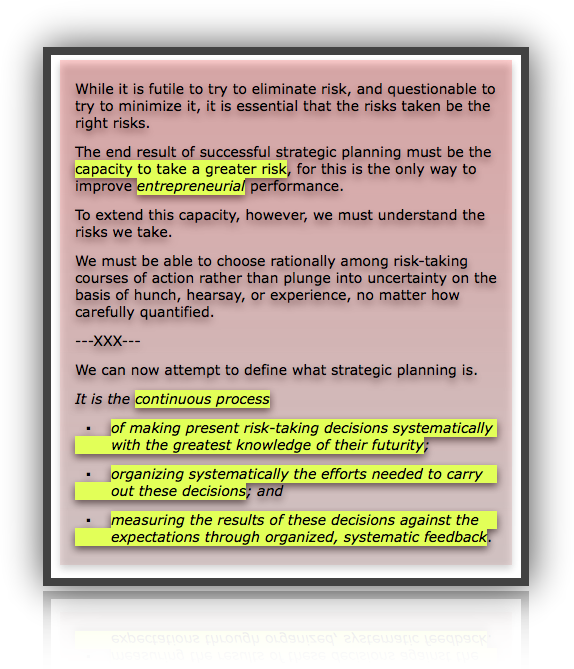

The final conclusion is that we need a new approach to the process in which we make our value decisions between different objective areas—the budgeting process.

And in particular do we need a real understanding of that part of the budget that deals with the expenses that express these decisions, that is, the “managed” and “capital” expenditures.

Commonly today, budgeting is conceived as a financial process.

But it is only the notation that is financial; the decisions are entrepreneurial.

Commonly today, managed expenditures and capital expenditures are considered quite separate.

But the distinction is an accounting (and tax) fiction and misleading; both commit scarce resources to an uncertain future; both are, economically speaking, capital expenditures.

And they, too, have to express the same basic decisions on survival objectives to be viable.

Finally, today, most of our attention in the operating budget is given, as a rule, to other than the managed expenses, especially to the variable expenses, for that is where, historically, most money was spent.

But, no matter how large or small the sums, it is in our decisions on the managed expenses that we decide on the future of the enterprise.

Indeed, we have little control over what the accountant calls variable expenses—the expenses which relate directly to units of production and are fixed by a certain way of doing things.

We can change them, but not fast.

We can change a relationship between units of production and labor costs (which we, with a certain irony, still consider variable expenses despite the fringe benefits).

But within any time period these expenses can only be kept at a norm and cannot be changed.

This is, of course, even more true for the expenses in respect to the decisions of the past, our fixed expenses.

We cannot make them undone at all, whether these are capital expenses or taxes or what have you.

They are beyond our control.

In the middle, however, are the expenses for the future which express our risk-taking value choices: the capital expenses and the managed expenses.

Here are the expenses on facilities and equipment, on research and merchandising, on product development and people development, on management and organization.

This managed expense budget is the area in which we really make our decisions on our objectives.

(That, incidentally, is why I dislike accounting ratios in that area so very much, because they try to substitute the history of the dead past for the making of the prosperous future.)

We make decisions in this process in two respects.

First, what do we allocate people for?

For the money in the budget is really people.

What do we allocate people, and energy, and efforts to?

To what objectives?

We have to make choices, as we cannot do everything.

And, second, what is the time scale?

How do we, in other words, balance expenditures for long-term permanent efforts against any decision with immediate impact?

The one shows results only in the remote future, if at all.

The development of people (a fifteen-year job), the effectiveness of which is untested and unmeasurable, is, for instance, a decision on faith over the long range.

The other may show results immediately.

To slight the one, however, might, in the long range, debilitate the business and weaken it.

And, yet, there are certain real short-term needs that have to be met in the business—in the present as well as in the future.

Until we develop a clear understanding of basic survival objectives and some yardsticks for the decisions and choices in each area, budgeting will not become a rational exercise of responsible judgment; it will retain some of the hunch character that it now has.

But our experience has shown that the concept of survival objectives alone can greatly improve both the quality and effectiveness of the process and the understanding of what is being decided.

Indeed, it gives us, we are learning, an effective tool for the integration of functional work and specialized efforts and especially for creating a common understanding throughout the organization and common measurements of contribution and performance.

The approach to a discipline of business enterprise through an analysis of survival objectives is still a very new and a very crude one.

Yet it is already proving itself a unifying concept, simply because it is the first general theory of the business enterprise we have had so far.

It is not yet a very refined, a very elegant, let alone a very precise, theory.

Any physicist or mathematician would say: This is not a theory; this is still only rhetoric.

But at least, while maybe only in rhetoric, we are talking about something real.

(calendarize this?)

For the first time we are no longer in the situation in which theory is irrelevant, if not an impediment, and in which practice has to be untheoretical, which means cannot be taught, cannot be learned, and cannot be conveyed, as one can only convey the general.

This should thus be one of the breakthrough areas; and twenty years hence this might well have become the central concept around which we can organize the mixture of knowledge, ignorance, and experience, of prejudices, insights, and skills, which we call “management” today.

Technology, Management and Society (1970)

![]()

![]()