Managing in the Next Society

by Peter Drucker — his other books

top of the food-chain

Amazon Link: Managing in the Next Society

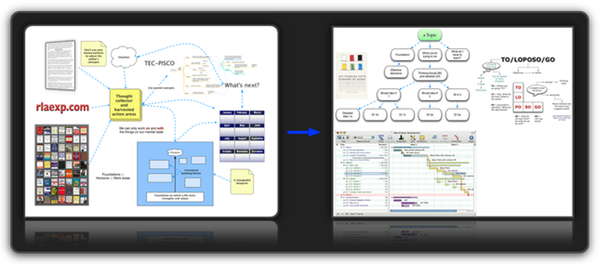

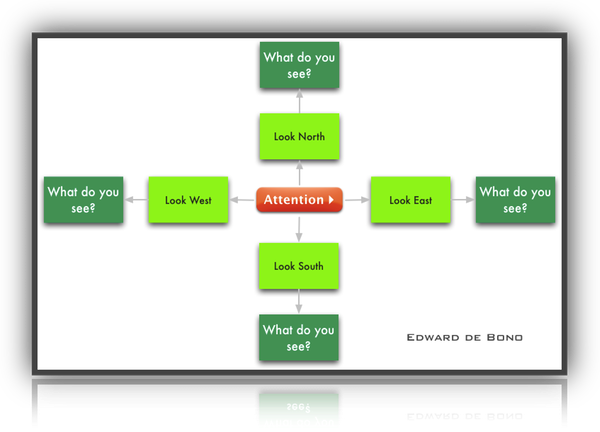

The brain can only see

what it

is prepared to see

«§§§»

To know something,

to really understand

something important,

one must look at it

from sixteen different angles.

People are perceptually slow,

and there is no shortcut

to understanding;

it takes a great deal of time. continue

«§§§»

Your thinking, choices, decisions

are determined by

what you’ve

“SEEN”

“Once perception

is directed in a certain direction

it cannot help but see,

and once something is seen,

it cannot be unseen”

«§§§»

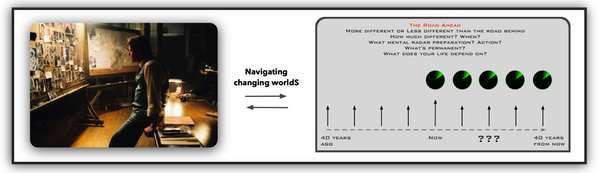

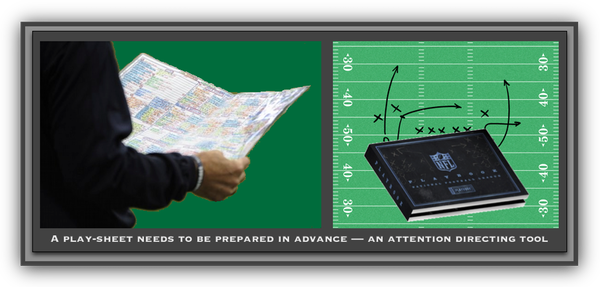

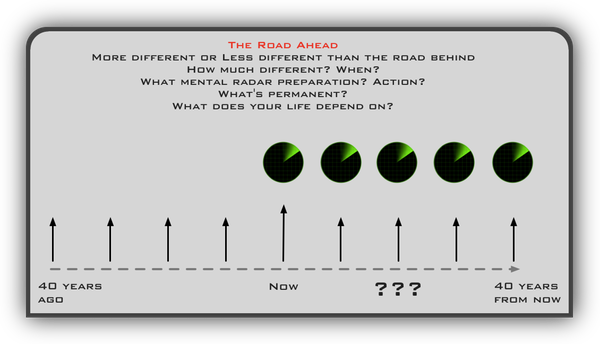

Being prepared for what comes next — and there’s no one to ask

Work has to make a life

finding and selecting the pieces of the puzzle

#Note the number of books about Drucker ↓

My life as a knowledge worker

Drucker: a political or social ecologist ↑ ↓

“I am not

a ‘theoretician’;

through my consulting practice

I am in daily touch with

the concrete opportunities and problems

of a fairly large number of institutions,

foremost among them businesses

but also hospitals, government agencies

and public-service institutions

such as museums and universities.

And I am working with such institutions

on several continents:

North America, including Canada and Mexico;

Latin America; Europe;

Japan and South East Asia.

Still, a consultant is at one remove

from the day-today practice —

that is both his strength

and his weakness.

And so my viewpoint

tends more to be that of an outsider.”

broad worldview ↑ ↓

Most mistakes in thinking ↑ are mistakes in PERCEPTION: …

Seeing only part of the situation;

Jumping to conclusions;

Misinterpretation caused by feelings …

#pdw larger ↑ ::: Books by Peter Drucker ::: Rick Warren + Drucker

Books by Bob Buford and Walter Wriston

Global Peter Drucker Forum ::: Charles Handy — Starting small fires

Post-capitalist executive ↑ T. George Harris

Your thinking, choices, decisions

are determined by

what you’ve “SEEN”

“Once perception is directed

in a certain direction

it cannot help but see,

and once something is seen,

it cannot be unseen”

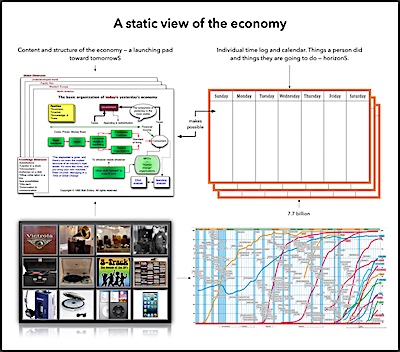

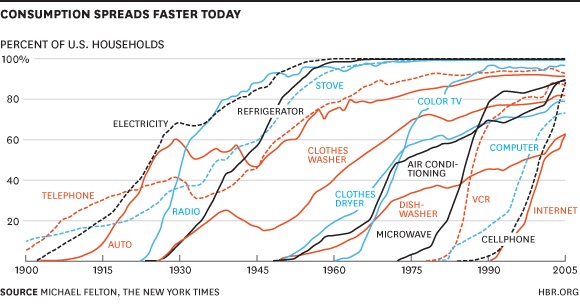

The speed of product and technology adoption

Work has to make a life

If you don’t design your own life

someone else will do it for you

↑ The Drucker Lectures:

Essential Lessons on

Management, Society, and Economy

↓

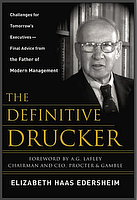

The Definitive Drucker:

Challenges For

Tomorrow's Executives

“More detailed map” ↑

About technology

A Year with Peter Drucker:

52 Weeks of Coaching

for Leadership Effectiveness

The Five Most Important Questions

You Will Ever Ask

About Your Nonprofit Organization

Danger of too much planning

Learning to Learn

↑ ecological awareness → operacy —

the skills of doing

The memo “THEY” don’t want you to SEE

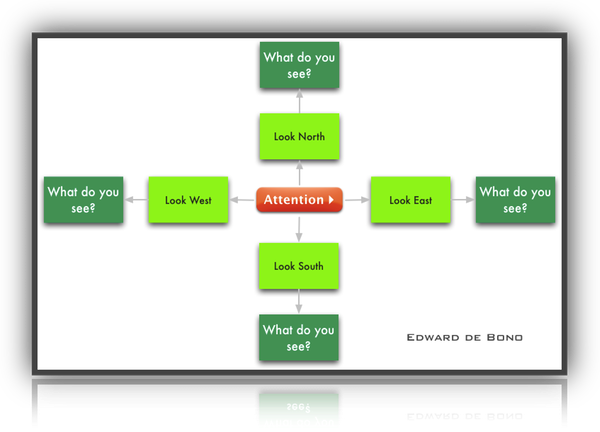

“The world around is full of a huge number of things

to which one could pay attention.

But it would be impossible

to react to everything at once.

So one reacts only to

a selected part of it.

The choice of attention area

determines the action or thinking that follows.

The choice of this area of attention

is one of the most fundamental aspects

of thinking.” — Edward de Bono

About management

Preface

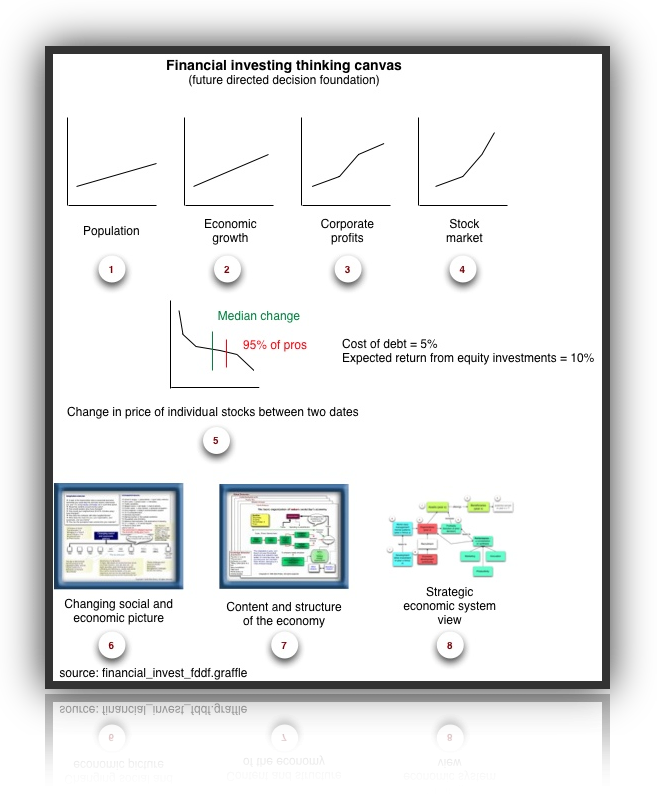

I did once believe in a New Economy.

The year was 1929 and I was a trainee in the European headquarters of a major Wall Street firm.

My boss, the firm’s European economist, was convinced that the Wall Street boom would go on forever; he wrote a brilliant book entitled Investment to prove “conclusively” that buying American common stock was the one absolutely foolproof way to get rich quick.

Being the firm’s youngest trainee—I was not yet twenty—I was recruited to be my boss’s research assistant, the book’s proofreader, and its index-maker.

The book was published two days before the New York stock market crash and disappeared without a trace—and a few days later, so did my job.

And so, when seventy years later, in the mid-1990s, there was all that talk of the New Economy and of a perpetual stock market boom, I had been there before.

The terms that the 1990s used were, of course, different from those of the 1920s—we then talked of “perpetual prosperity” rather than a New Economy.

But only the terms were different; everything else, the arguments, the logic, the predictions, the rhetoric, was practically the same.

But at the time when everyone began to talk of the New Economy, I became aware that Society was changing, and more and more so as the decade progressed.

It was changing fundamentally and not only in the developed countries, but in the emerging ones perhaps even more.

The Information Revolution was only one factor, and perhaps not even the most potent one.

Demographics were at least as important, especially the steadily falling birthrates in the developed and emerging countries with a resulting fast shrinkage in the number and proportion of younger people and in the rate of family formation.

And while the Information Revolution was but the culmination of a trend that had been running for more than a century, the shrinkage of the young population was a total reversal and unprecedented.

But there is also another total reversal, the steady decline of manufacturing as a provider of wealth and jobs to the point where, economically, manufacturing is becoming marginal in developed countries but, at the same time, in a seeming paradox, politically all the more powerful.

There is—again unprecedented—the transformation of the workforce and its splintering.

These changes, together with the social impacts of the Information Revolution, are the main themes of this book—and these changes have already happened.

Irreversibly, the Next Society is already here.

Some of the chapters in this book deal with traditional “management” topics, some do not.

And none deals with the “cure-alls,” the assertedly “infallible” tools and techniques that provided much of the substance for so many of the management best-sellers of the 1980s and 1990s.

Yet this is very much a book for executives and indeed very much a book about managing.

Dense reading and Dense listening and Thinking broad and Thinking detailed

For the thesis that underlies all the book’s chapters is that major social changes that are creating the Next Society will dominate the executive’s task in the next ten or fifteen years—maybe even longer.

They will be the major threats and the major opportunities for every organization, large or small, business or nonprofit, American—North and South, European, Asian, Australian.

Indeed it is the thesis underlying every chapter of this book that the social changes may be more important for the success or failure of an organization and its executives than economic events.

For half a century, from 1950 to the 1990s, enterprises in the free, noncommunist world and their executives could and did take society very much for granted.

There were rapid and profound economic and technological changes.

But society was very much a given.

Economic and technological changes will surely continue.

Indeed the concluding pages of this book—the section “The Way Ahead” in Part IV—argues that major new technologies are still ahead of us, and that most of them, with high probability, will have nothing or little to do with information.

But to be able to exploit these changes as opportunities for the enterprise—again, for both businesses and nonprofits, whether large or small executives will have to understand the realities of the Next Society and will have to base their policies and strategies on them.

To help them do this, to help them successfully manage in the Next Society, is the purpose of this book.

All the chapters in this book were written before the terrorist attacks on America in September of 2001.

All but two of them (chapters 8 and 15) were actually published before September 2001 and no attempt has been made to update the chapters.

(*The year of first publication is shown at the end of each chapter.)

Except for a few small cuts and corrections of typographical and spelling errors (and, in a few cases, changing the title back to my original title) each chapter is being published as it originally appeared.

This means, specifically, that “three years ago” in a chapter first published in 1999 refers to the year 1996; a sentence in the same chapter reading “three years hence” refers to the year 2002.

This will also enable the reader to judge whether this author’s anticipations and forecasts came true or were disproven by events.

The terrorist attacks of September 2001 should make this book even more relevant to the executive, and even more timely.

Terrorists and America’s response to them have profoundly changed world politics.

We clearly face years of world disorder, especially in the Mideast.

But in a period of unrest and rapid changes such as we surely face, one cannot successfully manage by being clever.

Management of an institution, whether a business, a university, a hospital, has to be grounded in basic and predictable trends that persist regardless of today’s headlines.

It has to exploit these trends as opportunities. (calendarize this?)

And these basic trends are the emergence of the Next Society and its new, and unprecedented, characteristics, especially

the global shrinking of the young population and the emergence of the new workforce;

the steady decline of manufacturing as a producer of wealth and jobs; and

the changes in the form, the structure, and the function of the corporation and of its top management.

In times of great uncertainty and unpredictable surprises, even basing one’s strategy and one’s policies on these unchanging and basic trends does not automatically mean success.

But not to do so guarantees failure.

Peter F. Drucker

Claremont, California

Easter 2002

- Managing in the Next Society (by Peter Drucker)

- Preface (above)

- The Information Society

- Business opportunities

- Entrepreneurs and Innovation

- The four entrepreneurial pitfalls

- Can large companies foster entrepreneurship?

- The rise of social entrepreneurship

- They're Not Employees, They're People

- Strangled in red tape

- The splintered organization

- Companies don't get it

- The key to competitive advantage

- Free managers—to manage people

- Financial Services: Innovate or Die

- A wider transformation

- Time for innovations

- Moving Beyond Capitalism? (link only includes the first part)

- The changing world economy

- The Rise of the Great Institutions

- Control over the Fief

- Needed autonomy

- The Global Economy and the Nation-State

- A true survivor

- The nation-state afloat

- Virtual money

- Breaking the rules

- Selling to the world

- War after global economics

- It's the Society, Stupid

- A heretics' view

- Descending from heaven

- Elites rule

- A policy about nothing

- The social contract

- It's the society, stupid

- On Civilizing the City

- Reality of rural life

- The need for community

- The next society (From The Economist)

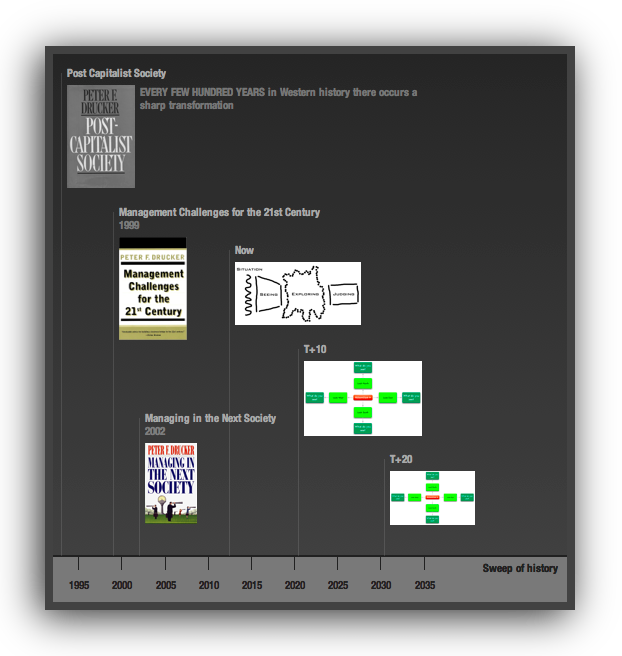

How did Drucker see these things? What did he look at to arrive at his observations?

- Knowledge is all

- The new protectionism

- The future of the corporation

- The new demographics

- Needed but unwanted

- A country of immigrants

- The end of the single market

- Beware demographic changes

- The new workforce

- His and hers

- Ever upward

- The price of success

- The manufacturing paradox

- Smaller numbers, bigger clout

- Will the corporation survive?

- Everything in its place

- Who needs a research lab?

- The next company

- From corporation to confederation

- The Toyota way

- The future of top management

- Life at the top

- Impossible jobs

- The way ahead

- Acknowledgments

- Index

See Marketing Moves and Chaotics: The Business of Managing and Marketing in the Age of Turbulence

Luther, Machiavelli, and the Salmon

(note the patterns ↓)

The railroad made the Industrial Revolution accomplished fact.

What had been revolution became establishment.

And the boom it triggered lasted almost a hundred years.

The technology of the steam engine did not end with the railroad.

It led in the 1880s and 1890s to the steam turbine, and in the 1920s and 1930s to the last magnificent American steam locomotives, so beloved by railroad buffs.

… the importance of accessing, interpreting, connecting, and translating KNOWLEDGE …

But the technology centered on the steam engine and in manufacturing operations ceased to be central.

Instead the dynamics of the technology shifted to totally new industries that emerged almost immediately after the railroad was invented, not one of which had anything to do with steam or steam engines.

The electric telegraph and photography were first, in the 1830s, followed soon thereafter by optics and farm equipment.

The new and different fertilizer industry, which began in the late 1830s, in short order transformed agriculture.

Public health became a major and central growth industry, with quarantine, vaccination, the supply of pure water, and sewers, which for the first time in history made the city a more healthful habitat than the countryside.

At the same time came the first anesthetics.

With these major new technologies came major new social institutions: the modern postal service, the daily paper, investment banking, and commercial banking, to name just a few.

Not one of them had much to do with the steam engine or with the technology of the Industrial Revolution in general.

It was these new industries and institutions that by 1850 had come to dominate the industrial and economic landscape of the developed countries.

This is very similar to what happened in the printing revolution—the first of the technological revolutions that created the modern world.

In the fifty years after 1455, when Gutenberg had perfected the printing press and movable type he had been working on for years, the printing revolution swept Europe and completely changed its economy and its psychology.

But the books printed during the first fifty years, the ones called incunabula, contained largely the same texts that monks, in their scriptoria, had for centuries laboriously copied by hand: religious tracts and whatever remained of the writings of antiquity.

Some seven thousand titles were published in those first fifty years, in thirty-five thousand editions.

At least sixty seven hundred of these were traditional titles.

In other words, in its first fifty years, printing made available—and increasingly cheap—traditional information and communication products.

But then, some sixty years after Gutenberg, came Luther’s German Bible—thousands and thousands of copies sold almost immediately at an unbelievably low price.

With Luther’s Bible the new printing technology ushered in a new society.

It ushered in Protestantism, which conquered half of Europe and, within another twenty years, forced the Catholic Church to reform itself in the other half.

Luther used the new medium of print deliberately to restore religion to the center of individual life and of society.

And this unleashed a century and a half of religious reform, religious revolt, religious wars.

At the very same time, however, that Luther used print with the avowed intention of restoring Christianity, Machiavelli wrote and published The Prince (1513), the first Western book in more than a thousand years that contained not one biblical quotation and no reference to the writers of antiquity.

In no time at all The Prince became the “other best-seller” of the sixteenth century, and its most notorious but also most influential book.

In short order there was a wealth of purely secular works, what we today call literature: novels and books in science, history, politics, and soon, economics.

It was not long before the first purely secular art form arose, in England—the modern theater.

Brand-new social institutions also arose: the Jesuit order, the Spanish infantry, the first modern navy, and finally, the sovereign national state.

In other words, the printing revolution followed the same trajectory as did the Industrial Revolution, which began three hundred years later, and as does the Information Revolution today.

What the new industries and institutions will be, no one can say yet.

No one in the 1520s anticipated secular literature, let alone the secular theater.

No one in the 1820s anticipated the electric telegraph, or public health, or photography.

The one thing (to say it again) that is highly probable, if not nearly certain, is that the next twenty years will see the emergence of a number of new industries.

At the same time, it is nearly certain that few of them will come out of information technology, the computer, data processing, or the Internet.

This is indicated by all historical precedents.

But it is true also of the new industries that are already rapidly emerging.

Biotechnology, as mentioned, is already here.

So is fish farming.

Twenty-five years ago salmon was a delicacy.

The typical convention dinner gave a choice between chicken and beef.

Today salmon is a commodity and is the other choice on the convention menu.

Most salmon today is not caught at sea or in a river but grown on a fish farm.

The same is increasingly true of trout.

Soon, apparently, it will be true of a number of other fish.

Flounder, for instance, which is to seafood what pork is to meat, is just going into oceanic mass production.

This will no doubt lead to the genetic development of new and different fish, just as the domestication of sheep, cows, and chickens led to the development of new breeds among them.

But probably a dozen or so technologies are at the stage where biotechnology was twenty-five years ago—that is, ready to emerge.

There is also a service waiting to be born: insurance against the risks of foreign exchange exposure.

Now that every business is part of the global economy, such insurance is as badly needed as was insurance against physical risks (fire, flood) in the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, when traditional insurance emerged.

All the knowledge needed for foreign-exchange insurance is available; only the institution itself is still lacking.

The next two or three decades are likely to see even greater technological change than has occurred in the decades since the emergence of the computer, and also even greater change in industry structures, in the economic landscape, and probably in the social landscape as well. (calendarize this?)

“Managers are synthesizers

who bring resources together

and have that ability to “smell” opportunity and timing.

Today perceptiveness is more important than analysis.

In the new society of organizations,

you need to be able to recognize patterns

to see what is there

rather than what you expect to see.”

— Interview: Post-Capitalist Executive

Writing out what you see

is different from saying it

mentally or verbally. It makes you decide.

Additionally, what are the implications of what you see?

Dense reading and Dense listening

Thinking Broad and Thinking Detailed by Edward de Bono

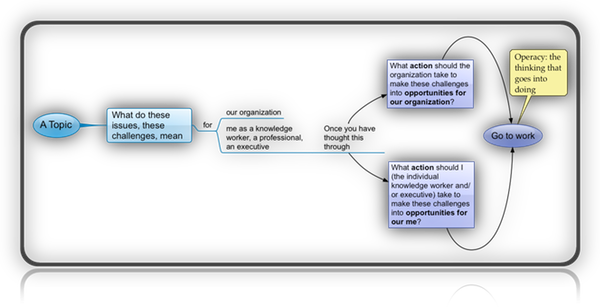

What do these issues, these challenges mean for …

… an alternative

Water logic vs. rock logic

Operacy — the thinking that goes into doing

On Fortune's Role in Human Affairs and How She Can Be Dealt With

The individual in entrepreneurial society

… one thing worth being remembered for

is the difference one makes in the lives of people more

Wisdom → broad

thinking broad and thinking detailed

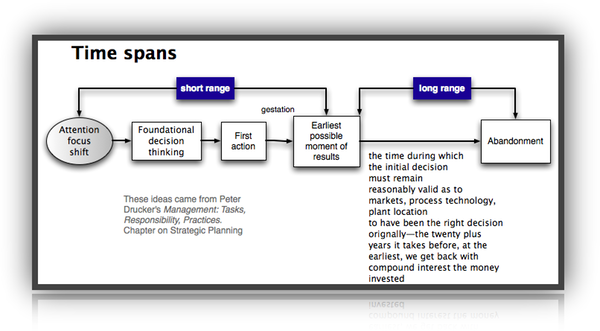

Danger of too much planning

Knowledge and technology

Knowledge economy and knowledge polity

Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Managing in the Next Society

A Year with Peter Drucker:

52 Weeks of Coaching for Leadership Effectiveness

Freedom (et al.) is the heaviest burden

laid on mankind

Origins of The Practice of Management

We need to measure knowledge workers’ productivity.

How do we do that?

We begin by asking even lower-level knowledge workers three things:

What are your strengths and what should you put work into?

What should this company expect from you and in what time span?

And what information do you need to do your work and what information do you owe?

I learned this many years ago when I worked with one of the world’s biggest pharmaceutical companies.

A new CEO expected each department head to explain what their function should contribute.

The head of research said, “You can’t measure research.”

So we arranged meetings with eleven to thirteen people at a time, working through the research department.

I asked, “Looking over the last five years, what have you contributed which made a difference?

What do you think you can contribute in the next three years?”

Suppose they’d found some hormonal function that changed our understanding of how the pancreas works.

It might be twenty years, if ever, before that became a product.

However, repeatedly—this was the early 1960s—there’d been important contributions that evaporated.

They didn’t fit the market for pharmaceutical companies or how the medical director saw the company.

So we had to change that.

We brought the medical, marketing, and manufacturing people into what was happening in research.

They doubled the utilization—the yield from research—within five or six years.

What about American health care, which seems mired in contradictions?

It’s no worse than any other country’s.

They’re all bankrupt.

It’ll be a growth sector simply because health care and education together will be 40 percent of the gross national product within twenty years.

Already, they’re at least a third.

Furthermore, as more and more services by government agencies will be outsourced, it will make little difference whether the organization which gets a contract to clean the streets is for profit or not for profit.

It won’t be in the market economy.

If I could voice one comment on your magazine and the present e-commerce and e-business-to-business concern altogether, it’s so far focused on business.

Yet I think the greatest e-commerce impact may be in higher education and health care.

It makes possible a rational restructuring of health care.

Eighty percent of demands in health care require only a nurse-practitioner.

What she needs to know is when to refer a patient to a physician, which largely now can become a matter of using information technology.

I’ve worked with hospitals which are the only ones within two hundred miles.

It’s incredible what a difference information technology has made to them.

Take Grand Junction, Colorado, with thirty-four thousand inhabitants.

Denver and Salt Lake City two sizable cities—are both about two hundred miles away.

Now Grand Junction’s hospital can make a diagnosis of a patient which brings in the University of Colorado medical school in Denver and whatever medical school Salt Lake City has.

That answers that small hospital’s basic problem, which was that they couldn’t build their own specialist center.

Was this that hospital’s only problem?

Could it even be profitable, given that area’s population base?

You may have a million people for whom Grand Junction represents the nearest decent hospital.

I’ve worked with a consortium of twenty-five such hospitals, from West Virginia to Oregon.

Information technology can make them the equivalent of a big-city university hospital.

With that patient with convulsions and vertigo that nobody in Grand Junction can diagnose, for example, now the doctor says, this may be a thyroid problem and we’ll talk to Salt Lake City.

The specialist in Salt Lake City diagnoses a cyst on the thyroid pressing the carotid—this was an actual case—and says, “I’ve done some of those, but my colleague in Denver is better.

Helicopter him there.”

Three days later, the patient is back in Grand Junction.

Thus, in health care, information technology has already made a fabulous impact.

In education, its impact will be greater.

However, attempts to put ordinary college courses on the Internet are a mistake.

Marshall McLuhan was correct.

The medium not only controls how things are communicated, but what things are communicated.

On the Web, you must do it differently.

How so?

You must redesign everything.

Firstly, you must hold students’ attention.

Any good teacher has a radar system to get the class’s reaction, but you don’t have that online.

Secondly, you must enable students to do what they cannot do in a college course, which is go back and forth.

So on-line you must combine a book’s qualities with a course’s continuity and flow.

Above all, you must put it in a context.

In a college course, the college provides the context.

In that on-line course you turn on at home, the course must provide the background, the context, the references.

What about on-line education’s potential in the developing world?

For example, the Indian government has begun a program to put an on-line PC in each village for education.

My prejudices show.

In the early 1950s, President Truman sent me to Brazil to persuade the government there that with the new technology, we could wipe out illiteracy in five years at no cost.

The Brazilian teachers’ union sabotaged it.

We have possessed the technology to eliminate illiteracy for a long time.

Let me point out that the one great achievement of Mao’s government was to eliminate illiteracy in China.

Not by means of a new technology, but a very old one: the student who has learned to read teaches the next one.

Teachers have obstructed this everywhere because it threatens their monopoly.

Yet older students teaching younger students is the quickest way.

It’s what the Chinese have done.

For the first time the great majority of Chinese understand and can speak Mandarin.

You have the country unified not only by script, but by language.

It’s still only 70 percent.

But it was 30 when Mao came in.

We can make the new technology available to the remotest village in the Amazon.

The obstacles are, first, enormous resistance by teachers, who see themselves threatened.

Secondly, it isn’t true that you’ve support for education in every third-world country.

I worked hard in Colombia and helped found the Universidad del Valle in Cali.

We had a very difficult time in those small coffee growing towns because parents expected children to be at work in the fields at age eleven.

In India that’s a great problem.

Moreover, schools are an equalizing force.

That’s a tremendous obstacle in Indian provinces like Orissa, say, where the upper castes would bitterly fight admission of lower-class children.

Let’s return to health care.

Some people insist that market forces can be a cure-all for US. health care.

Given situations like these rural hospitals where little opportunity for profit exists, is that true?

No.

Market forces cannot be the cure-all for health care.

I always put my cards on the table.

I have been the consultant to two major national health care systems.

One for fifty years, one for thirty.

The idea that American health care is in particularly bad shape is nonsense.

They’re all in total disarray.

The reason is that they’re based on the facts of 1900.

The worst is either the German or the Japanese.

As I said, 80 percent of demands on a health care system are routine problems a nurse-practitioner can handle.

You face two issues with a nurse-practitioner.

First, you must ensure she doesn’t go beyond her competence, so you emphasize she should overrefer to the medical center, not underrefer.

The second problem is that a nurse-practitioner doesn’t have the authority to change anybody’s lifestyle.

For three thousand years we’ve built the mystique of the M.D.

When the doctor says you must lose fifteen pounds, and the nurse practitioner says it, you hear something different.

Then there’s the 20 percent of health care which requires modern medicine.

Incidentally, I’m going to shock you.

Medical advances since antibiotics have had no impact on life expectancy.

They are wonderful for tiny groups, but statistically insignificant.

The great changes have been in the workforce.

When I was born, 95 percent of all people worked in manual jobs—most of them dangerous, debilitating jobs.

You’ve heard of Franz Kafka, haven’t you?

Of course.

You know he was a great writer, don’t you?

But Franz Kafka also invented the safety helmet.

He was the great man in factory inspection and workmen’s compensation.

Kafka was the workmen’s compensation-factory safety man for what’s now the Czech Republic, which was Bohemia and Moravia before World War I. Our next door neighbor was the top workmen’s compensation-factory safety man for Austria.

Kafka was his idol.

When Kafka [was dying] outside of Vienna of throat tuberculosis, Dr. Kuiper—our neighbor—pedaled on his bike at five each morning for two hours to visit the dying Kafka, then took the train to work.

After Kafka’s death, nobody was more surprised than Dr. Kuiper to discover he’d been a writer.

Kafka got the gold medal of, I think, the American Safety Congress for 1912 because as a result of his safety helmet, the steel mills in what is [now] the Czech Republic for the first time killed fewer than twenty-five workers per one thousand a year.

Did you know that Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Massachusetts employs as many people to administer coverage for 2.5 million New Englanders as are employed in Canada to administer coverage for 27 million Canadians?

Yes.

And it isn’t true.

You are comparing…

Apples and oranges?

No.

Apples and beavers.

The Canadian system doesn’t administer health care.

It pays fixed rates, that’s all.

What we do now, the Canadian system doesn’t.

It doesn’t tell any doctor what to do.

It just says, for this you get X dollars in Ontario and Y dollars in Saskatchewan.

Blue Cross—in Massachusetts particularly—is trying to be an HMO: a health care provider, not a health care payer.

The Canadian system is not managed care, it’s managed costs.

What should happen with American health care?

Let me say that if we had listened to Mr. Eisenhower, who wanted catastrophic health care for everybody, we would have no health care problems.

What shut him down, as you may not have heard, was the UAW.

In the 1950s, the only benefit the unions could still promise was company-paid health care.

Under the Eisenhower principle—where for everybody who spent more than 10 percent of their taxable income for health expenditures, government would pay—this would have been eliminated.

So the UAW killed it with help from the American Medical Association.

Still, the AMA wasn’t that powerful.

The UAW was.

You’ve talked about demographic changes, with more old people in the developed nations and more younger people, for the next forty years, in the developing nations.

Do you worry how it will be for the young in a world dominated by the old?

Look.

In the developed countries, with the exception of the U.S. , the number of young people is already going down sharply.

In the U.S. , it will begin diminishing in fifteen or eighteen years.

Since 1700, we’ve tacitly assumed that population grows, and the foundation grows faster than the top.

So this is unprecedented.

We have no idea what it means.

There are indications.

We know that in the Chinese coastal cities, the middle class spends more on the one child they are allowed than they used to spend on all four that they had before.

Those kids are horribly spoiled.

That’s true in this country, too.

When I look at what ten-year-olds expect to own, it’s unthinkable for my generation.

Also, when you say young people, in the developed countries that will mean, very heavily, immigrants, not children.

They’re immigrants, whether a Mexican entering southern California, a Nigerian entering Spain, or a Ukrainian entering Germany.

These will be young, in that the average age of an immigrant into the developed countries is between eighteen and twenty-eight.

They represent a very heavy capital investment in their upbringing, yet aren’t adequately educated.

We don’t know what that means.

Perhaps tremendous additional productive power and tremendous demand for additional educational expenses.

We don’t know, we’ve never been there.

But it is predictable that today’s youth culture will not last forever.

It’s an old insight that the prevailing culture is made by the fastest-growing population group.

That will not be young people.

New Approaches to Information

We have heard endlessly that we are living in an Information Revolution, and indeed we are.

Forty years ago when the computer first came out, most people saw it as an extremely fast adding machine.

A few of us, however, took it more seriously and saw it as a new way to process information.

We were convinced that within twenty to thirty years, new information would transform the job of running the business.

But, so far, except perhaps for the military, our new information capacities have had practically no impact on the way we run businesses.

(He’s not talking about an organization’s operations)

Where we have seen a tremendous impact is on the way we run operations.

Two examples: My grandson, who is completing his internship in architecture, recently showed me the software he is using to complete his final thesis—a project for a large architecture firm.

This firm put in a bid to design the heating, lighting, and plumbing for a new prison building.

The software my grandson showed me can, literally in the twinkling of an eye, do work that once took hundreds of individuals to complete.

Meanwhile, in medical schools and teaching hospitals, virtual reality presentations are providing a new and effective way to train surgeons.

Up until now, surgeons would not actually see surgical operations until their final year of residency—before then, they would see only the back of the surgeon who was performing the operation.

Today, young surgeons can actually do what is essential to learning surgical techniques—practice—and with virtual reality they can do this without endangering the well-being of patients.

In businesses across the board, information technology has had an obvious impact.

But until now that impact has been only on concrete elements—not intangibles like strategy and innovation.

Thus, for the CEO, new information has had little impact on how he or she makes decisions.

That is going to have to change.

Let’s take two positions most CEOs are familiar with.

Today, practically every corporation has a chief financial officer, to whom the accounting department reports.

This is our oldest information system; in many ways it’s obsolete, but companies cling to accounting because it’s what they understand—it’s familiar.

Likewise many companies have a management information systems officer, or chief information officer, who presides over a computer system that is generally enormously expensive.

But neither of these officers knows one blessed thing about information.

They understand data, and within fifteen years, the two will be under one manager and both will be different.

The changes currently under way in accounting are the most substantive since the 1920s.

They include activity-based accounting and economic chain accounting and so on.

Essentially, we are changing basic record-keeping to accommodate present economic reality something accounting was never designed to do.

At the same time, we are merging this with our data-producing capacity, so you will have an information system that will look very different.

And yet it will not give the CEO the information he or she needs most: what goes on outside the enterprise.

One of the biggest mistakes I have made during my career was coining the term profit center, around 1945.

The truth is that inside the business, there are only cost centers.

The only profit center is a customer whose check hasn’t bounced.

We know literally nothing about the outside, and yet, even if you are the leading business in an industry, the great majority of the people who buy your kind of product or services are not your customers.

If you have 30 percent of the market, you are the giant.

But that means that 70 percent of the customers do not buy your product or your services, and we know nothing about them.

These “noncustomers” are particularly important because they represent a source of information that can help you gauge the changes that will affect your industry.

How so?

If you look at the changes in major industries over the last forty years, you’ll see that practically all of them occurred outside the existing market, or product, or technology.

Whatever the business, senior people need to spend more time outside their own shop.

There is no question that getting to know your noncustomers is far from easy, but it really is the only way to expand your knowledge.

The people I know, for example, who have been successful building their business in Japan made a point of studying Japanese history before making contact.

We are fortunate in the United States because of our cultural diversity—and we should use that asset to our advantage.

In the nineteenth century, you could take for granted that each major industry spawned a specific technology, and that technologies from separate industries would never meet.

This is the hypothesis on which all the great research labs have been founded, beginning with Siemens in Germany in 1869.

That assumption no longer works.

Technologies now crisscross each other all the time, and productivity is no guarantee of achievement.

In the last thirty years, Bell Laboratories has been more productive than at any other time in its history—but what is its track record during this period for major technological breakthroughs?

There is no question that businesses need to understand what goes on outside their spheres.

But so far there is almost no information—and what little exists is at best anecdotal.

We’re only beginning to learn how to quantify this information.

So far, whenever anyone claims to have done so, I know that somebody has put a thumb on the scale.

The Rise of Knowledge Work

What is going to be the one and only comparative advantage a developed country will have tomorrow?

One lesson we have all learned, in part from our experience during the two World Wars, is how to train people almost overnight.

Shortly after the end of the Korean War, I was sent to Korea.

The country had experienced far more destruction than either Germany or Japan had in World War II.

Moreover, for fifty years preceding the war, the Japanese had not allowed any higher education in Korea.

Yet, with the proper support and training, it took less than ten years to convert a purely rural (and primitively so, at that) labor force into a highly productive one.

You can no longer depend on the competitive advantage of knowledge.

Technology travels incredibly fast.

The only real advantage the United States has—perhaps for the next thirty or forty years—is a substantial supply of something that is not easily created overnight: knowledge workers.

In the United States, there are 12 million college students.

In China, the top students are extremely well trained, but there are only 1.5 million college students out of a population of 1.2 billion.

If we had the same ratio in the United States, we would have just 250,000 college students.

Now, we can argue that we may have a few too many, especially in the law schools, but still, the productivity of knowledge work and knowledge workers is visible.

The trouble is that we haven’t worked on it.

Productivity

Today’s knowledge workers are probably less productive than in the past because their schedules are filled with activities that don’t reflect their training or talent.

The best-trained (does not mean most knowledgeable) people in the world are American nurses.

Yet whenever we make a study on nurses, we find that 80 percent of their time is spent on things they aren’t trained for.

They spend time filling out papers for which nobody apparently has any need.

No one knows what happens to those papers, but they have to be filled out nonetheless and the task falls to the nurses.

In department stores, salespeople spend 70 to 80 percent of their time serving not the customer but the computer.

How to make the knowledge worker more appropriately productive is a challenge we will need to face seriously over the next twenty years.

With manual work, we start with the question “How do you do the work?”

You take this work for granted.

In knowledge work, you start with the questions “What do you do and what should you be doing?”

Answering these questions is critical if we want to maintain our competitive advantage.

Physical resources no longer provide much of an advantage, nor does skill.

Only the productivity of knowledge workers makes a measurable difference—and right now it is quite poor.

Why is the social sector growing in Japan, where the community has been so strong?

Well, two things are happening.

First, the traditional community structure is crumbling.

Second, educated women who have worked for a few years, then left work to have children, who then go off to school, are bored.

What kind of social problems does Japan have?

When you reach fifty-five years of age in Japan, you are essentially thrown on the dung heap—even though you will probably live thirty years longer.

So, the elderly organize clubs, from sports to ikebana flower arranging, to keep themselves occupied.

One of the most successful new social sector groups in Japan engages in that most unJapanese of activities: “meals on wheels” for the elderly who can’t get out.

Young people don’t take care of the elderly anymore.

Yet, the government fought the establishment of the meals-on-wheels program because it meant they had to admit their old people were not doing so well.

Indeed, this is a blot on the Japanese honor.

But it is a fact.

There is also a tremendous need among teenagers and school-age children to drive them to and from school, to supervise homework, and tutor those who do not make the top grades.

Nobody outside Japan seems to know that while 20 percent of Japanese students excel, the rest who don’t are simply forgotten.

The social sector tries to provide for these kids.

There are also conversation and reading classes in English for Japanese women who learned a little in high school or at work and want to maintain it.

There are now over 185,000 of these circles, even in small towns.

In Japan now there is even an Alcoholics Anonymous Association.

I don’t know how big they are so far, but sometimes it seems every salaryman in the country could become a member.

In the US., though, the size of the social problems means they just can’t be taken care of by voluntary associations, can they?

Perhaps not entirely.

But the scope of activities is just tremendous.

More than 50 percent of Americans work at least four hours a week in a voluntary association of some sort, in the church or the community.

And the solutions to community problems they come up with are highly creative.

I have come over the years to learn a very important lesson: Practical examples of how to solve social problems matter greatly because others will replicate them.

To this end, each year the Drucker Foundation gives a prize to a voluntary association to highlight their example so they can be replicated.

One year, we gave the prize to a very small group run by an immigrant who found a way to bring together the worst, most unproductive welfare mothers and the most seriously disabled children.

This led to a situation where the disabled were cared for and, in time, the welfare mothers became qualified to be fully employed and well paid.

There is another project we highlighted by a Lutheran church in St. Louis.

In their area, they found that about two-fifths of the homeless, mostly families, need very little to get back on their feet.

The first thing the church did was assess what homeless families needed most.

The answer was self-respect.

So the members of the congregation would buy dilapidated houses and find volunteers to refurbish them into comfortable middle-class homes.

Then they moved the homeless family in.

That by itself changed their outlook on life.

Then designated church members would help the family with their bills and in finding work.

In the end, about 80 percent of the families in their program went permanently off any kind of assistance.

Then there are organizations such as the Girl Scouts that are reaching new levels of participation.

A few years ago they were down to about five hundred thousand volunteers.

Today they are up to about nine hundred thousand.

The old volunteer was usually a middle-class housewife bored at home.

The new volunteer is more often than not a professional woman who has postponed having children, but likes to be with girls on the weekend after having worked all week in a male environment.

For most of the last twenty-five years, I have worked with the fast-growing Protestant megachurches in the U.S. , which I believe are one of the most significant social phenomena in the world today.

They teach community activism and encourage people to live their faith by taking action to improve the lives of others.

While the traditional churches may be dying in some ways, in others they are being transformed.

Take the Catholic Church in America.

Pope John Paul II has been very careful to place conservative bishops in the American church because it frightens him.

It is not so much the theological problems, married priests, and ordained women that bother him, but the enormous upsurge of activity in the dioceses that is lay-driven and not controlled by the bishop.

In one of the larger Midwestern dioceses that I know, there used to be seven hundred priests; now there are barely more than two hundred and fifty.

There are almost no nuns now—but there are twenty-five hundred laywomen.

Every parish has a lay administrator who is a woman.

All the priest does is say Mass and dispense the sacraments.

Women run the rest of the show entirely as volunteers.

That is a long way from the days of the altar girl.

Why does the US. have such a large and vital third sector when compared to other countries, including other Western countries?

No other country has anywhere near the scale of activity the U.S. has in the nonprofit sector because, elsewhere essentially, the civil servants of the modern national state destroyed the community sector.

In France it is almost a crime to do anything in the community.

The voluntary sector in Victorian England was quite large.

It dealt with poverty, with crime, with prostitution, with housing.

But in the 20th century the welfare state almost destroyed it.

In Europe the basic struggle was to free the state from the domination of the church, which explains why continental Europe has such an enormous anticlerical tradition.

In the U.S., it was the other way around.

When Jonathan Edwards established the doctrine of separation of church and state around 1740, it was in order to free the church from the state.

Anticlericalism has never had a place in this country.

Because of this freedom, the U.S. developed a tradition of religious pluralism and nongovernmental churches.

And with pluralism, there was competition among the denominations for members.

Out of that competition came a tradition of community involvement which doesn’t exist in other countries.

Aside from Jefferson’s University of Virginia, all colleges in the U.S. were denominational until Oberlin was established in 1833.

The Asian Crisis

The economic troubles in Asia don’t really interest me all that much because what you can fix with money is unlikely to be much of a problem unless you are stupid.

And Asians are not stupid.

Fundamentally, the Asian crisis is not economic, but social.

Across the entire region, the social tensions are so high that it reminds me of the Europe of my youth that descended into two world wars.

In many ways, we see in Asia the same kind of tensions that arose in Europe as a result of the “great disturbance” of the mass Industrial Revolution and the rapid urbanization that accompanied it.

Only Asia’s disturbance has taken place at a vastly accelerated pace.

When I first came to know Korea in the 1950s, it was 80 percent rural and practically nobody had more than a high school education because the occupying Japanese hadn’t allowed it.

(Only the Christian missionary schools could function because they couldn’t be suppressed by the Japanese, which explains why 30 percent of Koreans are Christians.)

There was no industry because the Japanese didn’t allow anyone to have more than a few employees.

Today, Korea is almost 90 percent urban, an industrial powerhouse, and its population is highly educated.

All in forty years.

The dislocations of this topsy-turvy development in only four decades have been explosive.

Add to this the unrivaled stupidity of the Korean businessmen who learned nothing from the Japanese next door about how to treat their workers.

Japan learned the hard way—through two bloody strikes that almost overturned the government in 1948 and 1954—to treat human beings like human beings.

(Nobody seems to know that Japan had had the world’s worst history of labor troubles dating back to 1700.)

When foreigners would visit an electronics plant in Korea, if one of the assembly-line women so much as even looked up, she was taken out and beaten for not paying attention to her work.

The autocrats of Korean business not only treated the workers horribly, but kept control of all the money and power in their companies.

They treated middle management like black Mississippi schoolteachers in the old days of segregation.

The autocrats then worked hand in hand with the military to keep their power and keep the workers down.

This is finally all changing now with Kim Dae Jung, but it has left a legacy of deep hatred between Korean business and its workers.

In Malaysia, despite efforts over the years by the government, the tension between the Malays, who are 70 percent of the population, and the Chinese, who are 30 percent, remains high.

Prime Minister Mohamad Mahathir once asked me to advise him on how to keep the Malays in school.

So, I visited some villages and found that everything grows there—plantains, bananas, coconuts, apples.

And they have pigs and chickens.

Nobody has to lift a finger to eat.

If they can make enough money for a TV set and a motorbike by working a few hours a year, what more would they want?

Why stay in school beyond the third grade?

The Chinese in Malaysia, in contrast, not only stay beyond third grade but go to graduate school in the U.S.

They speak English as well as Malay.

They know three Chinese dialects.

So, they control things more than Malaysia’s leaders want to admit.

And they are resented as a result.

It is usually reported that the ethnic Chinese constitute only about 3 percent of the 200 million people of Indonesia, 100 million of whom do not live on Java.

This is only true statistically, as the Chinese constitute more than 20 percent of the population in the three major cities, including Jakarta.

In any event, since half a million Chinese were killed in the takeover in the 1960s, they knew they had to stand with the army and its boss, Suharto.

So, the Chinese made the money for the Suharto clan and the military and the Muslim population resents it deeply.

Collectively, the “overseas Chinese” have become one of the world’s great economic powers.

They own businesses wherever they are.

They often constitute the professional class wherever they are and are influential with the leadership group.

With the exception of Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong—which are all Chinese—they are resented everywhere else.

China itself has had a peasant rebellion every fifty years since 1700.

The last one, under Mao, succeeded in 1949.

So, the time is due for another revolt.

The problem has always been the same, and it remains today: There are too many unemployed or unemployable peasants with no place to go.

Some estimate that today as many as 200 million peasants constitute a “floating population” that wander around looking for work.

And they are not likely to find it.

If the Chinese government is serious about shutting down inefficient state industries, another 80 to 100 million people will be on the streets.

Perhaps the history of fascism and war in Europe makes me oversensitive.

But I know from personal experience that when social tensions are high, it does not take much more than an accident to set things off.

Therefore, I am afraid for Asia.

Also see Drucker on Asia — A Dialogue Between Peter Drucker and Isao Nakauchi

On Japan

The leading power in Asia is Japan.

But Japan is essentially a European country.

Worse, it is a traditional nineteenth-century European country.

And that is why it is mired in paralysis today.

Like the Austria of my father’s day or France in its heyday, Japan is a country run by a civil service bureaucracy.

Politicians don’t matter and have always been suspect.

If they are incompetent or corrupt, it is to be expected.

But if the civil servants turn out to be corrupt and incompetent, it is a terrific shock.

Japan is in shock today.

Just as in Japan, the senior civil servant in countries like Germany or France who oversees a certain sector of the economy would usually graduate at about age fifty-five to become a board member of the businesses he was regulating or the head of that sector’s trade group at a very fat salary.

Japan is only more organized.

The bureaucrat remains loyal to his ministry until the end and defends its turf against all intrusions—even at the cost, in the case of the finance ministry, of sinking the economy.

He is then placed by the ministry in a very lucrative “counselorship” in the industry.

The idea that Japanese industry is efficient and competitive is total nonsense.

They still have the lowest per cent of their economy—about 8 percent and mostly in automobiles and electronics—exposed internationally.

As a consequence, Japan has very little world economy experience.

Most of its industry is protected and grotesquely inefficient.

If, for example, Japan were to open its paper industry to imports, the three big Japanese paper companies would be gone in forty-eight hours.

Whenever there has been an opening in the Japanese economy, Americans and other foreigners have taken over.

The foreign exchange business in Japan is completely in the hands of foreign companies.

To be a foreign exchange trader, you need to be at least bilingual because you need to speak English.

Not much Japanese is spoken in Geneva.

When a tiny opening in asset management was allowed, 100 percent of the business was taken over by foreign companies within six months.

There are few trained asset managers in Japan.

When I look at a Japanese bank today, I see the same bank my father managed in Austria right after World War I.

There were four people to do what one could.

In 1923, they still didn’t believe in typewriters.

They had no adding machines.

Though woefully inefficient and overstaffed, the bank was profitable because the many craftsmen of the Austro-Hungarian empire didn’t mind paying 5 percent to the bank.

They couldn’t get any credit elsewhere.

Then the world changed.

The empire was dismantled, loans went bad, customers stopped borrowing.

The already overstaffed bank had to take on employees sent back from Prague or Cracow.

The banks lost their profits and were eaten by their overhead costs.

This is Japan today.

Because of a practice dating to 1890 that obliges companies to hire from a list of universities to ensure a supply of graduates, businesses continued as recently as two years ago to hire even when business was declining.

They were afraid they would be cut off the list of companies that would receive graduates.

I know one company that hired two hundred and eighty people from six universities, even though the company was shrinking.

So, the new hires sit around all day with nothing to do.

In the evening they go out and get drunk with the boss.

This is work?

How can Japan as a nineteenth-century European state make it in the hypercompetitive twenty-first century?

For all I have said, don’t underrate the Japanese.

They have an incredible ability to make brutal, 180-degree radical changes overnight.

And since there is no tradition of compassion in Japan, the emotional scars of these changes are tremendous.

Though for four hundred years no non-European country had anywhere near the level of international trade Japan had, in 1637 they closed to the outside world.

And they did it within six months.

The dislocation was unbelievable.

In 1867, with the Meiji Restoration, they opened up again—overnight.

Nineteen forty-five was obviously a different story, as they were defeated in war.

When the dollar was devalued about ten years ago, the Japanese wasted no time moving manufacturing out of Japan to cheaper spots in Asia.

They established partnerships with overseas Chinese and gained an almost unbeatable lead as producers in mainland China.

Japan is very capable of dramatic about-faces.

Once they reach a certain critical mass of consensus, the change is very swift.

My guess is that it will take a major scandal to trigger change.

A banking collapse may provide this.

So far, they have been postponing tackling their weak financial system, hoping the problem would go away or could be liquidated step by step.

But, as time goes on, it doesn’t look like that is possible.

The New Workforce

A century ago, the overwhelming majority of people in developed countries worked with their hands: on farms, in domestic service, in small craft shops, and (at that time still a small minority) in factories.

Fifty years later, the proportion of manual workers in the American labor force had dropped to around half, but factory workers had become the largest single section of the workforce, making up 35 percent of the total.

Now, another fifty years later, fewer than a quarter of American workers make their living from manual jobs.

Factory workers still account for the majority of the manual workers, but their share of the total workforce is down to around 15 percent—more or less back to what it had been one hundred years earlier.

Of all the big developed countries, America now has the smallest proportion of factory workers in its labor force.

Britain is not far behind.

In Japan and Germany, their share is still around a quarter, but it is shrinking steadily.

To some extent this is a matter of definition.

Data-processing employees of a manufacturing firm, such as the Ford Motor Company, are counted as employed in manufacturing, but when Ford outsources its data processing, the same people doing exactly the same work are instantly redefined as service workers.

However, too much should not be made of this.

Many studies in manufacturing businesses have shown that the decline in the number of people who actually work in the plant is roughly the same as the shrinkage reported in the national figures.

Before the First World War there was not even a word for people who made their living other than by manual work.

The term service worker was coined around 1920, but it has turned out to be rather misleading.

These days, fewer than half of all nonmanual workers are actually service workers.

The only fast-growing group in the workforce, in America and in every other developed country, is “knowledge workers”—people whose jobs require formal and advanced schooling.

They now account for a full third of the American workforce, outnumbering factory workers by two to one.

In another twenty years or so, they are likely to make up close to two-fifths of the workforce of all rich countries.

The terms knowledge industries, knowledge work, and knowledge worker are only forty years old.

They were coined around 1960, simultaneously but independently; the first by a Princeton economist, Fritz Machlup, the second and third by this writer.

Now everyone uses them, but as yet hardly anyone understands their implications for human values and human behavior, for managing people and making them productive, for economics and for politics.

What is already clear, however, is that the emerging knowledge society and knowledge economy will be radically different from the society and economy of the late twentieth century, in the following ways.

First, the knowledge workers, collectively, are the new capitalists.

Knowledge has become the key resource, and the only scarce one.

This means that knowledge workers collectively own the means of production.

But as a group, they are also capitalists in the old sense: Through their stakes in pension funds and mutual funds, they have become majority shareholders and owners of many large businesses in the knowledge society.

Effective knowledge is specialized.

That means knowledge workers need access to an organization—a collective that brings together an array of knowledge workers and applies their specialisms to a common end product.

The most gifted mathematics teacher in a secondary school is effective only as a member of the faculty.

The most brilliant consultant on product development is effective only if there is an organized and competent business to convert her advice into action.

The greatest software designer needs a hardware producer.

But in turn the high school needs the mathematics teacher, the business needs the expert on product development, and the PC manufacturer needs the software programmer.

Knowledge workers therefore see themselves as equal to those who retain their services, as “professionals” rather than as “employees.”

The knowledge society is a society of seniors and juniors rather than of bosses and subordinates.

The Manufacturing Paradox

In the closing years of the twentieth century, the world price of the steel industry’s biggest single product—hot-rolled coil, the steel for car bodies—plunged from $460 to $260 a ton.

Yet these were boom years in America and prosperous times in most of continental Europe, with automobile production setting records.

The steel industry’s experience is typical of manufacturing as a whole.

Between 1960 and 1999, both manufacturing’s share in America’s GDP and its share of total employment roughly halved, to around 15 percent.

Yet in the same forty years manufacturing’s physical output doubled or tripled.

In 1960, manufacturing was the center of the American economy, and of the economies of all other developed countries.

By 2000, as a contributor to GDP it was easily outranked by the financial sector.

The relative purchasing power of manufactured goods (what economists call the terms of trade) has fallen by three-quarters in the past forty years.

Whereas manufacturing prices, adjusted for inflation, are down by 40 percent, the prices of the two main knowledge products, health care and education, have risen about three times as fast as inflation.

In 2000, therefore, it took five times as many units of manufactured goods to buy the main knowledge products as it had done forty years earlier.

The purchasing power of workers in manufacturing has also gone down, although by much less than that of their products.

Their productivity has risen so sharply that most of their real income has been preserved.

Forty years ago, labor costs in manufacturing typically accounted for around 30 percent of total manufacturing costs; now they are generally down to 12-15 percent.

Even in cars, still the most labor-intensive of the engineering industries, labor costs in the most advanced plants are no higher than 20 percent.

Manufacturing workers, especially in America, have ceased to be the backbone of the consumer market.

At the height of the crisis in America’s “rust belt,” when employment in the big manufacturing centers was ruthlessly slashed, national sales of consumer goods barely budged.

What has changed manufacturing, and sharply pushed up productivity, are new concepts.

Information and automation are less important than new theories of manufacturing, which are an advance comparable to the arrival of mass production eighty years ago.

Indeed, some of these theories, such as Toyota’s “lean manufacturing,” do away with robots, computers, and automation.

One highly publicized example involves replacing one of Toyota’s automated and computerized paint-drying lines by half a dozen hair-dryers bought in a supermarket.

Manufacturing is following exactly the same path that farming trod earlier.

Beginning in 1920, and accelerating after the Second World War, farm production shot up in all developed countries.

Before the First World War, many Western European countries had to import farm products.

Now there is only one net farm importer left: Japan.

Every single European country now has large and increasingly unsalable farm surpluses.

In quantitative terms, farm production in most developed countries today is probably at least four times what it was in 1920 and three times what it was in 1950 (except in Japan).

But whereas at the beginning of the twentieth century farmers made up the largest single group in the working population in most developed countries, now they account for no more than 3 percent in any developed country.

And whereas at the beginning of the twentieth century agriculture was the largest single contributor to national income in most developed countries, in 2000 in America it contributed less than 2 percent to GDP.

Manufacturing is unlikely to expand its output in volume terms as much as agriculture did, or to shrink as much as a producer of wealth and of jobs.

But the most believable forecast for 2020 suggests that manufacturing output in the developed countries will at least double, while manufacturing employment will shrink to 10-12 percent of the total workforce.

In America, the transition has largely been accomplished already, and with a minimum of dislocation.

The only hard-hit group have been African-Americans, to whom the growth in manufacturing jobs after the Second World War offered quick economic advancement, and whose jobs have now sharply fallen.

But by and large, even in places that relied heavily on a few large manufacturing plants, unemployment remained high only for a short time.

Even the political impact in America has been minimal.

But will other industrial countries have an equally easy passage?

In Britain, manufacturing employment has already fallen quite sharply without causing any unrest, although it seems to have produced social and psychological problems.

But what will happen in countries such as Germany or France, where labor markets remain rigid and where, until very recently, there has been little upward mobility through education?

These countries already have substantial and seemingly intractable unemployment, e. g., in Germany’s Ruhr and in France’s old industrial area around Lille.

They may face a painful transition period with severe social upheavals.

The biggest question mark is over Japan.

To be sure, it has no working-class culture, and it has long appreciated the value of education as an instrument of upward mobility.

But Japan’s social stability is based on employment security, especially for blue-collar workers in big manufacturing industry, and that is eroding fast.

Yet before employment security was introduced for blue-collar workers in the 1950s, Japan had been a country of extreme labor turbulence.

Manufacturing’s share of total employment is still higher than in almost any other developed country around a quarter of the total—and Japan has practically no labor market and little labor mobility.

Psychologically, too, the country is least prepared for the decline in manufacturing.

After all, it has owed its rise to great-economic-power status in the second half of the twentieth century to becoming the world’s manufacturing virtuoso.

One should never underrate the Japanese.

Throughout their history they have shown unparalleled ability to face up to reality and to change practically overnight.

But the decline in manufacturing as the key to economic success confronts Japan with one of the biggest challenges ever.

The decline of manufacturing as a producer of wealth and jobs changes the world’s economic, social, and political landscape.

It makes “economic miracles” increasingly difficult for developing countries to achieve.

The economic miracles of the second half of the twentieth century—Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore—were based on exports to the world’s rich countries of manufactured goods that were produced with developed-country technology and productivity but with emerging-country labor costs.

This will no longer work.

One way to generate economic development may be to integrate the economy of an emerging country into a developed region—which is what Vicente Fox, the new Mexican president, envisages with his proposal for total integration of “North America,” i. e., the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Economically this makes a lot of sense, but politically it is almost unthinkable.

The alternative—which is being pursued by China—is to try to achieve economic growth by building up a developing country’s domestic market.

India, Brazil, and Mexico also have large enough populations to make home-market-based economic development feasible, at least in theory.

But will smaller countries, such as Paraguay or Thailand, be allowed to export to the large markets of emerging countries such as Brazil?

The decline in manufacturing as a creator of wealth and jobs will inevitably bring about a new protectionism, once again echoing what happened earlier in agriculture.

For every 1 percent by which agricultural prices and employment have fallen in the twentieth century, agricultural subsidies and protection in every single developed country, including America, have gone up by at least 1 percent, often more.

And the fewer farm voters there are, the more important the “farm vote” has become.

As numbers have shrunk, farmers have become a unified special interest group that carries disproportionate clout in all rich countries.

Protectionism in manufacturing is already in evidence, although it tends to take the form of subsidies instead of traditional tariffs.

The new regional economic blocks, such as the European Union, NAFTA, or Mercosur, do create large regional markets with lower internal barriers, but they protect them with higher barriers against producers outside the region.

And non-tariff barriers of all kinds are steadily growing.

In the same week in which the 40 percent decline in sheet-steel prices was announced in the American press, the American government banned sheet-steel imports as “dumping.”

And no matter how laudable their aims, the developed countries’ insistence on fair labor laws and adequate environmental rules for manufacturers in the developing world acts as a mighty barrier to imports from these countries.

See production

The Future of Top Management

As the corporation moves toward a confederation or a syndicate, it will increasingly need a top management that is separate, powerful, and accountable.

This top management’s responsibilities will cover the entire organization’s

direction, planning, strategy, values, and principles;

its structure and its relationship between its various members;

its alliances, partnerships, and joint ventures; and its research, design, and innovation.

It will have to take charge of the management of the two resources common to all units of the organization: key people and money.

It will represent the corporation to the outside world and maintain relationships with governments, the public, the media, and organized labor.

Life at the Top

An equally important task for top management in the Next Society’s corporation will be to balance the three dimensions of the corporation: as an economic organization, as a human organization, and as an increasingly important social organization.

Each of the three models of the corporation developed in the past half-century stressed one of these dimensions and subordinated the other two.

The German model of the “social market economy” put the emphasis on the social dimension, the Japanese one on the human dimension, and the American one (“shareholder sovereignty”) on the economic dimension.

None of the three is adequate on its own.

The German model achieved both economic success and social stability, but at the price of high unemployment and dangerous labor-market rigidity.

The Japanese model was strikingly successful for twenty years, but faltered at the first serious challenge; indeed it has become a major obstacle to recovery from Japan’s present recession.

Shareholder sovereignty is also bound to flounder.

It is a fair-weather model that works well only in times of prosperity.

Obviously the enterprise can fulfill its human and social functions only if it prospers as a business.

But now that knowledge workers are becoming the key employees, a company also needs to be a desirable employer to be successful.

Paradoxically, the claim to the absolute primacy of business gains that made shareholder sovereignty possible has also highlighted the importance of the corporation’s social function.

The new shareholders whose emergence since 1960 or 1970 produced shareholder sovereignty are not “capitalists.”

They are employees who own a stake in the business through their retirement and pension funds.

By 2000, pension funds and mutual funds had come to own the majority of the share capital of America’s large companies.

This has given shareholders the power to demand short-term rewards.

But the need for a secure retirement income will increasingly focus on people’s minds on the future value of the investment.

Corporations, therefore, will have to pay attention both to their short-term business results and to their long-term performance as providers of retirement benefits.

The two are not irreconcilable, but they are different, and they will have to be balanced.

Over the past decade or two, managing a large corporation has changed out of all recognition.

That explains the emergence of the “CEO superman,” such as Jack Welch of GE, Andrew Grove of Intel, or Sanford Weill of Citigroup.

But organizations cannot rely on supermen to run them; the supply is both unpredictable and far too limited.

Organizations survive only if they can be run by competent people who take their job seriously.

That it takes genius today to be the boss of a big organization clearly indicates that top management is in crisis.

Impossible Jobs

The recent failure rate of chief executives in big American companies points in the same direction.

A large proportion of CEOs of such companies appointed in the past ten years were fired as failures within a year or two.

But each of these people had been picked for his proven competence, and each had been highly successful in his previous jobs.

This suggests that the jobs they took on had become un-doable.

The American record suggests not human failure but systems failure.

Top management in big organizations needs a new concept.

Some elements of such a concept are beginning to emerge.