|

Don’t let the title fool you.

This book and particularly this part of the book could be of enormous benefit for 99.999 percent of adults if they could practice it in their lives.

Information is very important.

Information is easy to teach.

Information is easy to test.

It is not surprising that so much of education is concerned with information.

Thinking is no substitute for information but information may be a substitute for thinking.

Most theological definitions grant God perfect and complete knowledge.

When knowledge is perfect and complete there is no need for thinking.

In some areas we might be able to achieve complete information and then those areas become routine matters that require no thinking.

In the future we shall hand over these routine matters (AI?) to computers.

Unless we have complete information we need thinking in order to make the best use of the information we have.

When our computers and information technology give us more and more information we also need thinking in order to avoid being overwhelmed and confused by all the information.

When we are dealing with the future we need thinking because we can never have perfect information about the future.

For creativity, design, enterprise and doing anything new, we need thinking.

We need thinking in order to make even better use of information that is also available to our competitors.

So information is not enough.

We do need thinking as well.

Unfortunately there is a difficult dilemma.

All information is valuable.

Every new bit of information is of increasing value because it adds to what we already know.

So how do we get the courage to reduce the amount of time we spend on teaching information in order to find time to teach the thinking skills that are needed to make the best use of the information?

A tradeoff is clearly needed.

Find “Information” in Peter Drucker’s work

Intelligence and Thinking

The belief that intelligence and thinking are the same has led to two unfortunate conclusions in education:

1. That nothing needs to be done for students with a high intelligence because they will automatically be good thinkers.

2. That nothing can be done for students without a high intelligence because they cannot ever be good thinkers.

The relationship between intelligence and thinking is like that between a car and the driver of that car.

A powerful car may be driven badly.

A less powerful car may be driven well.

The power of the car is the potential of the car just as intelligence is the potential of the mind.

The skill of the car driver determines how the power of the car is used.

The skill of the thinker determines how intelligence is used.

I have often defined thinking as: ‘the operating skill with which intelligence acts upon experience’.

Many highly intelligent people often take up a view on a subject and then use their intelligence to defend that view.

Since they can defend the view very well they never see any need to explore the subject or listen to alternative views.

This is poor thinking and is part of the ‘intelligence trap’.

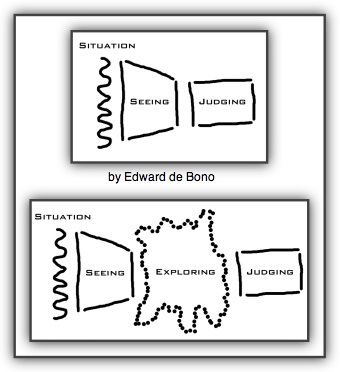

In the diagram below we can see that one thinker sees the situation and instantly judges it.

Another thinker sees the situation, then proceeds to explore the situation and only then proceeds to judge it.

The highly intelligent person may carry out the ‘seeing’ and ‘judging’ very well indeed, but if the ‘exploring’ is absent that is bad thinking.

Highly intelligent people are usually good at solving puzzles or problems where all the pieces are given.

They are less good at situations which require them to find the pieces and to assess the value of the pieces.

Finally there can be an ego problem.

Highly intelligent people do like to be right.

This may mean that they spend their time attacking and criticizing others since it is so easy to prove the others wrong.

It also may mean that highly intelligent people are unwilling to take speculative risks because they cannot then be sure they are right.

There is, of course, nothing to prevent highly intelligent people also being excellent thinkers.

But this does not follow automatically.

There is need to develop the skill of thinking.

Cleverness and Wisdom

In school, in puzzles, in tests, in examinations and in our value systems we put all the emphasis on cleverness.

A clever young man may make a great deal of money on Wall Street but his personal life may be a mess.

Cleverness is a sharp-focus camera lens: wisdom is a wide-angle lens.

We pay much less attention to wisdom than we do to cleverness.

This is mainly because we believe that wisdom comes only with age and experience and that you cannot possibly teach wisdom.

This is a fallacy.

Wisdom can be taught.

It is one of the main functions of this book to teach wisdom.

Wisdom depends heavily on perception.

It is a matter of teaching perception - not just logic.

Does Thinking Have to Be Difficult?

Why do we always try to develop people’s thinking by giving them tasks which are too difficult for them to do?

It is obvious that if the thinking task is too easy, there is no effort required, no sense of achievement, and nothing learned.

In almost all areas of skill development (tennis, skiing, music, cooking) we use tasks that are moderately difficult.

In other words the tasks can be done, but as we do them we have to practice the skills we have.

This builds up confidence and fluency in the skill.

Tasks that are almost impossible destroy confidence.

That is why so many people are turned off thinking.

They find it boring because it is too difficult.

There is no joy of performing if you cannot perform.

I do not believe that brain-teasers, puzzles and mathematical games are good ways to teach thinking.

That is why the thinking tasks and exercises used in this book are not difficult.

Furthermore the belief that if you can do very difficult things then you can also do all things that are less difficult is not supported by human experience.

Many people who are capable of very difficult mental feats sometimes seem less able to handle simpler tasks.

How to Be an Intellectual

The first rule of intellectualism is: ‘If you do not have much to say, make it as complex as possible.’

A true intellectual has as deep a fear of simplicity as a farmer has of droughts.

If there is no complexity, what is there to work with or write about?

I have on occasion talked to audiences of educators who have more or less said: ‘Please make your talk complicated enough for us to be impressed - but then it could be too complicated to be practical.’

There is no end to the complexity of descriptions.

You could divide a simple pencil into ten parts if you wished and then proceed to describe all ten parts and the relationship of the parts.

Once you have a handful of concepts you can choreograph the most complex of dances.

There is no limit to the word games that can be played with words.

You comment on the complexity of others and also on the comments of commentators.

And so the process feeds upon itself.

Quite soon comment becomes more important than creativity and we esteem this as ‘scholarship’.

Some people find this process unattractive and unnecessary.

This is particularly true of those who are interested in practical outcomes.

They come to equate ‘intellectualism’ with ‘thinking’ and get turned off thinking as a result.

That is a pity.

You can be a thinker without being an intellectual.

Indeed many intellectuals are not particularly good thinkers.

Reactive and Pro-Active Thinking

In school it is very practical to put work-sheets, textbooks, and blackboard texts in front of students.

The students are then asked to ‘react’ to what is before them.

For these practical reasons almost all the thinking taught in school is ‘reactive’.

‘Here is something - what do you think of it?’

You cannot easily ask students to go out and organize a business.

You cannot easily ask students to solve a real problem or undertake a real project.

It simply is not practical in a school setting.

It also happens that this reactive type of thinking fits in with the intellectual tradition of scholarship: how do we react to what is already in existence?

But school and education is not a game unto itself.

Real life involves a great deal of ‘pro-active’ thinking.

This means going out and doing things.

All the information is not given - you have to find it.

Something is not placed before you.

If you just sit in your chair nothing will happen.

It is easy enough to eat in a restaurant if the meal is placed before you.

But buying the food (or even growing it) and cooking it are different matters.

It is not the fault of education that pro-active thinking is not so easy to handle as reactive thinking.

But it is the fault of education to suppose that reactive thinking is sufficient.

The New Word ‘Operacy’

Everyone knows what literacy and numeracy mean.

I invented the word ‘operacy’ several years ago to cover the skills of ‘doing’.

There is a myth in education that ‘knowing’ is enough.

If you have sufficient knowledge, action is obvious and easy.

If you have a detailed map, getting about is easy.

The real world is different.

My many years of experience working with business and with government have shown that ‘doing’ is not at all easy.

There is a great deal of thinking involved in doing.

‘Gut feeling’ and ‘flying by the seat of the pants’ have long ceased to be sufficient.

There are people to be dealt with.

There are decisions to be made.

There are strategies to be designed and monitored.

There are plans to be made and implemented.

There is conflict, bargaining, negotiating and deal-making.

There are values to be assessed and trade-offs to be made.

All this requires a great deal of thinking.

All this requires a high degree of operacy.

In a competitive world, industrial nations that do not pay attention to operacy will be left behind.

On a personal level, youngsters who do not acquire the skills of operacy will need to remain in an academic setting.

Operacy involves such aspects of thinking as:

other people’s views

priorities

objectives

alternatives

consequences

guessing

decisions

conflict-resolution

creativity

and many other aspects

not normally covered in the type of thinking

used for information analysis.

These things are part of ‘pro-active’ thinking, not the usual ‘reactive’ thinking.

#80 Action → #88 Knowledge is useless until

translated into deeds

More on this type thinking and topic work

Critical Thinking

The traditions of Western thinking have put a very high emphasis on critical thinking.

This is partly due to the ancient Greek habits of thinking that were rediscovered in the Renaissance, and partly due to the need for Church thinkers in the Middle Ages to have a way of attacking heresy.

Critical thinking has a high value in only two states of society.

In a very stable society (as in the ancient Greek states and the Middle Ages) any new idea or intrusion that threatened change would need to be critically assessed.

The second situation is when society is brimming with constructive and creative energy and critical thinking is needed to sort out the valuable from the spurious.

Unfortunately neither of these two states is present today.

There is a tremendous need for change and there is a remarkable lack of new ideas and creative energy.

Imagine a project team of six brilliant critical thinkers who meet to discuss how they are going to cope with local pollution.

None of them can use their highly trained minds until someone comes up with an actual suggestion.

The difficulty is that critical thinking is ‘reactive’.

There has to be something to be ‘criticized’.

But where is that something going to come from?

The proposals and suggestions have to come from thinking that is constructive and creative and generative.

If we trained a person to avoid all errors in thinking, would that person be a good thinker?

Not at all.

If we trained a car driver to avoid all errors in driving, would that person be a good driver?

No, because that person could leave the car in the garage and so avoid any possibility of error.

Avoiding errors in driving is very valuable provided the car is actually going somewhere.

In the same way critical thinking is only valuable if we also have thinking that is constructive and creative.

It is no use having reins if you do not have a horse.

This point is a very serious one because many schools believe that it is sufficient to teach critical thinking.

They do this because it fits in with the usual emphasis on reactive thinking and also the traditional view of thinking.

Critical thinking is important and it does have a valuable place in thinking.

But it is only a part of thinking.

To say that a solitary wheel on a motor-car is inadequate is not to attack the worth of that wheel.

The dangers of believing critical thinking to be sufficient are many.

The best brains become trapped in this sort of thinking and do not develop the constructive and creative thinking skills that are so essential for society.

No time or effort in schools gets allocated to the constructive and creative aspects of thinking because the schools are deemed to be teaching ‘thinking’ already.

There is the dangerous arrogance that can arise from critical thinking because thinking that is free of error is seen as being absolutely right - even though it is based on inadequate information or perception (I shall return to this point later).

Skill in critical thinking without a matching skill in creative and constructive thinking makes it even more difficult for the needed new ideas to emerge.

Criticism is very much easier than creation.

The Adversarial System

In the USA there is one lawyer for every 350 citizens.

In Japan there is one lawyer for every 9,000 citizens.

The adversarial system is fundamental to Western thinking traditions.

It arises directly from the habits of critical thinking and the search for truth through adversarial dialogue.

Argument and debate are seen as the proper way to explore a subject because both parties are motivated.

But as the motivation rises so the exploration falls.

Would one party be inclined to bring forward a point which favoured the other side?

‘I am right - you are wrong.’

The adversarial system is the basis of politics, law, science (to some extent), and daily life.

Yet it is a very limited and defective system (this point is much more fully explored in my book I Am Right You Are Wrong*).

Polarities, polemics and conflicts are often made worse by the adversarial habit.

Conflicts more often require a ‘designed’ outcome than a trial of adversarial strength.

Challenge and Protest

‘Why do I have to get up in the morning?’

‘Why do I have to wear a tie?’

‘Why do I have to go to school?’

For many people the idea of ‘thinking’ has come to mean challenge, protest and argument.

This is why many governments, education authorities and even parents are often against the idea of teaching thinking.

They see thinking as causing endless disruption, protest and argument This has indeed been the case where the old fashioned notion of protest thinking has been dominant.

Yet the CoRT Thinking Program is now in use across many cultures and ideologies (Catholic, Protestant, Marxist, Islamic, Chinese etc.).

This is because the CoRT Program deals with constructive thinking, and this is rather different from the challenge and protest type of thinking.

Indeed some governments see the teaching of constructive thinking as the best protection against the blanket protest thinking which is all that is usually available to mentally energetic young people who have not been taught thinking.

Challenge thinking is closely related to critical thinking and adversarial thinking.

It is often felt that it is enough to protest or challenge and then the other side (or the authorities) will somehow ‘make things right’.

This is very much the thinking of a child demanding that its parents make things right.

There is a place for protest and much has been achieved by it: ecology concerns; moratorium on whale hunting; women’s rights; minority rights; safer cars etc.

Protest has its place in removing injustices and raising consciousness on an issue.

Where faults can be removed, protest may be enough.

In other areas which require creative and constructive thinking, protest is insufficient.

Yet there is a positive type of challenge, for without challenge we would never escape from old ideas in order to develop better ones.

This positive challenge is part of creative thinking.

In the negative challenge we attack the existing idea and ask the other party to defend the idea or to improve it.

In the positive challenge we acknowledge the value of the existing idea, then we create a new idea and lay it alongside the old idea.

We then seek to show that the new idea has merits and benefits.

Traditional revolutions have always been negative: define an enemy and struggle to overthrow the enemy.

It is time we developed designs for positive revolutions where there are no enemies but structures for making things better.

The Need to Be Right

Practical Thinking

If you work out a mathematics problem and get the right answer, you stop thinking.

You cannot be more right than right.

But real life is not like that.

You get an answer that seems ‘right’ but you go on thinking.

You go on thinking because there are usually other answers that are better (in terms of cost, less pollution, human values, competitive advantage etc.).

Our egos become very much tied up with being right.

In Western cultures that is the basis of argument and the adversarial system.

We are reluctant to admit defeat because of this ego problem.

The result is that our thinking is both aggressive and defensive but rarely constructive.

Theoretically everyone should be happy to lose an argument because that way you end up with more than you had at the beginning.

At meetings people want their idea to prevail - whether or not it is the best idea - because their ego is involved.

Because of this serious ego problem, an important aspect of learning to think is the development of techniques to detach thinking from the ego.

I shall be dealing with such techniques (like the six-hats technique) in this book.

Practical Thinking

Analysis and Design

Analysis is such an important part of our thinking tradition that almost the whole of our tertiary education system (colleges and universities) is directed towards developing analytical skills.

There is no doubt that analysis is a very important part of thinking.

It is through analysis that we break down complex situations into ones we can handle.

It is through analysis that we find the cause of a problem and seek to remove that cause.

As with critical thinking the question is not whether analysis has a value but whether it is enough.

If we now have two wheels on the motor-car, each wheel is wonderful but two wheels are still not good enough.

If you sit on a sharp object a quick analysis will allow you to remove the cause of your discomfort and to solve the problem.

Many problems can be solved by finding and removing the cause.

But there are also many other problems where we cannot find the cause.

Or, there may be multiple interrelated causes.

Or, we may find the cause (for example human greed) but are quite unable to remove the cause.

It is for this reason that we are so poor at solving such problems as drug abuse, third-world debt, pollution, traffic congestion etc.

To solve such problems analysis is not sufficient.

Yet all the problem-solvers in government and elsewhere are trained in analytical thinking.

There are many problems which require ‘design’ as much as they require analysis.

It is with design that we construct and create solutions.

Design thinking allows us to put things together to achieve what we desire.

It is not a matter of removing the cause of the problem but of constructing a solution.

Yet the amount of attention we give to design thinking - and creative and constructive thinking in education is tiny.

Design is seen as something for architects, graphic artists and fashion designers.

Yet design is a fundamental and very important part of thinking.

Design is at least as important as analysis.

Design includes all those aspects of thinking involved in putting things together to achieve an effect.

Because the traditions of Western academic thinking have been concerned with reactive thinking, with analysis, with critical thinking, with argument and with scholarship, such fundamentally important aspects of thinking as design have been virtually neglected.

Creative Thinking

In any self-organizing system there is an absolute mathematical necessity for creativity.

All the evidence suggests that the mind behaves as a self-organizing neural network.

Why have we not paid serious attention to creative thinking when this type of thinking is so obviously a key part of thinking (for improvement, for design, for problem-solving, for change, for new ideas etc.)?

There are two reasons why we have neglected creative thinking.

The first reason is that we have believed that nothing can be done about it.

We have considered creative thinking to be a mystical gift that some people have and others do not have.

There is nothing that can be done except to foster the creative gift in those who seem to have it.

The second reason we have neglected creative thinking is very interesting indeed.

Every valuable creative idea must always be logical in hindsight (after someone has had the idea).

If the new idea were not logical in hindsight we would never be able to regard it as valuable.

So we are only able to recognize those creative ideas which are indeed logical in hindsight.

The rest remain as crazy ideas.

We may catch up with some of the crazy ideas later or they may remain crazy for ever.

We then go on to assume that if the creative idea is logical in hindsight then we surely should have been able to reach the idea by the exercise of logic in the first place.

So there is no need for creativity, just a need for better logic.

This assumption is totally wrong.

But it is only in very recent years that we (actually a very small number of people working in this area) have come to realize that in a self-organizing information system an idea may be logical in hindsight but invisible in foresight.

This arises from the asymmetric nature of patterns - which also gives rise to humour.

Because our traditional thinking systems have only dealt with externally organized information systems (moving symbols according to logic rules) we have never been able to see this point.

Those who have been advocating creativity have been equally mistaken - but in a different direction.

Such people have believed that everyone is naturally creative but is inhibited.

This inhibition arises from the need to provide only the ‘right’ answers at school.

This inhibition arises from the fear of making mistakes or seeming ridiculous in business or professional life.

So if we can free people up and remove these inhibitions, we may unlock the natural creativity.

This is the basis of brainstorming and similar processes for freeing people from inhibitions.

Unfortunately, creativity is not natural to the brain.

The purpose of the brain is to allow experience to organize itself as patterns - and then to use these existing patterns.

So freeing people to be their natural selves will only make them slightly more creative (through being less inhibited).

If we want to be more creative, then we have to develop some Specific thinking techniques.

These techniques form part of what I called ‘lateral thinking’ (which I shall describe later in the book).

The techniques are unnatural and include methods of provocation which seem highly illogical.

In fact such methods are perfectly logical In patterning systems.

Creativity does not have to remain a mystical gift.

There are specific techniques of creative thinking and I shall be describing some of them in this book.

I shall also tell how the deliberate use of these techniques of lateral thinking contributed to the saving of the Olympic Games, which nearly came to an end in 1984.

How to Have Creative Ideas

Making the future

Logic and Perception

Everyone knows that logic is the basis of good thinking.

But is it?

Bad logic makes for bad thinking.

That is clear.

So good logic makes for good thinking?

Unfortunately, this does not follow at all.

Every junior logician knows that logic can never be any better than the starting premises or perceptions.

All logicians learn this - then many of them promptly forget it.

There is a fault in your computer.

Whatever you put in the output is always rubbish.

The fault is put right and the computer now works flawlessly.

If you put in good data you get good answers.

If you put in bad data you get bad answers (though you may not know this).

It is the same with logic.

Like the computer, logic is a servicing mechanism to service the data and perceptions we are using.

We should therefore be quick to point out bad logic but slow to accept the conclusions of good logic - because the perceptions may be inadequate.

I would say that about 85 per cent of ordinary thinking is a matter of perception.

Most of the faults in thinking are faults of perception (limited view etc.)

and not faults in logic.

Perception is the basis of wisdom.

Logic is important in technical matters and especially in closed systems like mathematics.

Because perception is so very important a part of thinking it is surprising that we persist in believing that logic is the basis of thinking.

This arises from our reactive thinking habits.

You put material with ready-made perceptions and information in front of students and then ask them to react.

Clearly logic is important since the perceptions are provided.

In real life we have to form our own perceptions.

Both logic and perception are important in the sense that both the engine and the wheels of a car are important.

If I were forced to choose between the two I would have to choose perception.

This is because the bulk of ordinary thinking depends on perception.

Also you can get quite far with skillful perception (as I shall explain later in the book), whereas skilled logic and poor perception can be dangerous.

In practice logic and perception are closely intertwined.

The emphasis of this book is on perception because this is the basis of wisdom and because this is the most neglected part of thinking.

See “From Analysis to Perception” in The Essential Drucker ::: Society ::: From analysis to perception)

Emotions, Feelings and Intuition

Contrary to what many people believe, emotions, feelings and intuition play a central role in thinking.

The purpose of thinking is to so arrange the world (in our minds) that we can apply emotion effectively.

In the end it is emotion that makes the choices and decisions.

The key question is when we use emotions and feelings.

There are those who feel that gut feeling is the only genuine guide to action.

Such people are suspicious of logic and word games because they feel that logic can be used to prove anything (which is true if you choose your perceptions and values carefully).

For such people true feeling becomes a sort of god.

This is dangerous because true feeling can be both vicious and also inadequate.

Much of man’s inhumanity to man has been based on the true feelings of the moment.

If, however, we develop our perceptions - including alternative ways of viewing the situation and then apply our values and feelings, the result is going to be much better.

Logic and argument cannot change feelings but perception can.

A stranger you meet on holiday is very helpful.

Then someone suggests he may be a con-man.

Looking at the person through this new perception may lead to a change of feeling.

Instead of excluding emotion, as is normally the case with the teaching of thinking, we must find ways of allowing emotion and feeling to play their proper part in our thinking.

In this book I shall describe such methods, for example the use of the ‘red hat’ in the six-hats technique.

Intuition does play a very important part in thinking.

But it is dangerous to sit back and do no thinking on the basis that somehow intuition will work it all out for you.

Intuition can be notoriously wrong sometimes - for example when dealing with probabilities.

But, as with emotions and feelings, intuition has a part to play in thinking.

There are probably two major influences on young people.

The first is the peer pressure of their friends, group and age bracket.

This provides the perceptions and values.

Unless a young person is able to think for himself or herself there is only the possibility of flowing with the group (even when this means such things as drug-taking).

The second major influence is the music of youth culture, with its repeated emphasis on the confused emotions of adolescence.

Like a field of wheat waving in the breeze, young minds are subjected to hours and hours of ‘he loves me - he loves me not’ - with variations.

Pop music is a very powerful medium and from time to time it does provide values, insights and even some thinking but, in general, the steady diet of anguished emotion does little to help individuals think for themselves.

Summary

In this section I have set out to correct some of the generally held misconceptions about thinking.

We need information but we also need thinking.

Thinking is not just a matter of cleverness and difficult problems.

Wisdom is even more important than cleverness.

Traditional thinking puts all the emphasis on critical thinking, argument, analysis and logic.

These are very important and I hope that nothing I write gives a different impression.

But these are only a part of thinking and it is very dangerous to assume they are sufficient.

In addition to critical thinking we need thinking that is constructive and creative.

In addition to argument we need exploration of the subject.

In addition to analysis we need the skills of design.

In addition to logic we need perception.

Traditionally we have been concerned mainly with reactive thinking: reacting to what is put before you.

But there is a whole other side of thinking.

This other side of thinking (pro-active) involves getting out and doing things and making things happen.

This requires ‘operacy‘ or the skills of doing.

It requires thinking that is constructive, creative and generative.

Much of thinking has had a negative flavour: challenge, attack, criticize, argue, prove wrong etc.

Is this really the only way to proceed - or can we obtain the same effects in a more constructive way?

I believe we can.

Creative thinking is very important.

We can begin to see how we can use creative thinking deliberately instead of just waiting for inspiration.

Emotions and feelings play a key part in thinking.

It is not a matter of excluding them but of using them at the right moment.

Finally, intelligence is a potential and for that potential to be fully used we need to develop thinking skills.

Without such skills the potential is under-used.

See Edward de Bono bio and book titles+

de Bono book search

One can … never be sure what the knowledge worker thinks—and yet thinking is her/his specific work; it is his/her “doing.”—Peter Drucker

Principles for Thinking

Larger view ↓

-

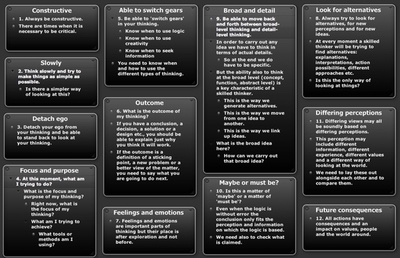

1. Always be constructive.

-

Too many people get into negative habits of thinking.

-

There is a lack of the constructive and generative aspects of thinking.

-

There are times when it is necessary to be critical.

-

We need to esteem constructive thinking above critical thinking.

-

2. Think slowly and try to make things as simple as possible.

-

Except for a few emergency occasions there is no great merit in thinking quickly.

-

A great amount of thinking can be done in a short time even if you think slowly.

-

Always try to make things simple.

-

3. Detach your ego from your thinking and be able to stand back to look at your thinking.

-

The biggest obstacle to skilled thinking is ego involvement: ‘I must be right,’ ‘My idea must be best.’ You need to be able to stand back and to look at what is going on in your thinking.

-

Just as you might be objective about your tennis skills you should be able to be objective about your thinking.

-

That is the way to develop any skill.

-

4. At this moment, what am I trying to do?

-

What is the focus and purpose of my thinking?

-

Right now, what is the focus of my thinking?

-

What am I trying to achieve?

-

What tools or methods am I using?

-

Without this sense of focus and purpose, thinking is just a matter of drifting along from moment to moment, from point to point.

-

Effective thinking requires this sense of focus and purpose.

-

5. Be able to ‘switch gears’ in your thinking.

-

Know when to use logic, when to use creativity, when to seek information.

-

In driving a car you select the appropriate gear.

-

In playing golf you select the appropriate club.

-

In cooking you select the appropriate pan.

-

Creative thinking is different from logical thinking and from seeking information.

-

A skilled thinker must be skilled at all the different types of thinking.

-

It is not enough just to be creative or critical.

-

You need to know when and how to use the different types of thinking.

-

6. What is the outcome of my thinking—why do I believe that it will work?

-

Unless you can spell out a clear outcome of your thinking you have wasted your time.

-

If you have a conclusion, a decision, a solution or a design etc., you should be able to explain just why you think it will work.

-

At this point how you got to the conclusion does not matter.

-

Explain to yourself—as you would to someone else—why you think the outcome is going to work.

-

If the outcome is a definition of a sticking point, a new problem or a better view of the matter, you need to say what you are going to do next.

-

7. Feelings and emotions are important parts of thinking but their place is after exploration and not before.

-

We are often told that feelings and emotions must be kept out of thinking.

-

This may be true for mathematics and science, but where people are concerned feelings and emotions are an important part of thinking.

-

But they need to be used at the right place.

-

If feelings are used at the beginning, perception is limited and choice of action may be inappropriate.

-

When exploration takes place first and when the alternatives have been examined, it is the role of feelings and emotions to make the final choice.

-

8. Always try to look for alternatives, for new perceptions and for new ideas.

-

At every moment a skilled thinker will be trying to find alternatives: explanations, interpretations, action possibilities, different approaches etc.

-

When someone claims that there are ‘only two alternatives’, the skilled thinker immediately tries to find others.

-

When an explanation is given as the only possible explanation, the skilled thinker tries to think of other explanations.

-

It is the same with the search for new ideas and new perceptions.

-

Is this the only way of looking at things?

-

9. Be able to move back and forth between broad-level thinking and detail-level thinking.

-

In order to carry out any idea we have to think in terms of actual details.

-

So at the end we do have to be specific.

-

But the ability also to think at the broad level (concept, function, abstract level) is a key characteristic of a skilled thinker.

-

This is the way we generate alternatives.

-

This is the way we move from one idea to another.

-

This is the way we link up ideas.

-

What is the broad idea here?

-

How can we carry out that broad idea?

-

10. Is this a matter of ‘maybe’ or a matter of ‘must be’?

-

Logic is only as good as the perception and information on which it is based.

-

This is a key principle because it deals with truth and logic.

-

When something is claimed to be true the claim is that it ‘must be’ so.

-

When it is claimed that a conclusion ‘must follow’ from what has gone before there is also an insistence on ‘must be’.

-

If we can challenge this and show that it is only a matter of ‘may be’, this may still have value but not the dogmatic value of truth and logic.

-

Even when the logic is without error the conclusion only fits the perception and information on which the logic is based.

-

So we need to look at this base.

-

In games and in belief systems we set things up to be true so they are true within that context.

-

In ordinary life we need always to distinguish between ‘may be’ and ‘must be’.

-

We need also to check what is claimed.

-

11. Differing views may all be soundly based on differing perceptions.

-

When there are opposing views we tend to feel that only one of these can be right.

-

If you believe that you are right, you set out to show that differing views must be wrong.

-

But differing views may be just as ‘right’.

-

A differing view may be soundly and logically based on a perception that is different from yours.

-

This perception may include different information, different experience, different values and a different way of looking at the world.

-

In settling arguments and disagreements we need to become aware of the differing perceptions on both sides.

-

We need to lay these out alongside each other and to compare them.

-

12. All actions have consequences and an impact on values, people and the world around.

-

Not all thinking results in action.

-

Even when thinking does result in action this action may be confined to a specific context such as mathematics, a scientific experiment, a game that is being played.

-

In general, thinking that results in an action plan, a problem solution, a design, a choice or a decision is going to be followed by action.

-

That action has future consequences.

-

That action has an impact on the world around.

-

This world includes values and other people.

-

Action does not take place in a vacuum.

-

The world is now a crowded place.

-

Other people and the environment are always affected by decisions and initiatives.

-

Summary

-

Twelve principles for thinking have been put forward here.

-

For each principle there is an explanation which describes the scope and the importance of that principle.

-

Some of the principles are concerned with how we operate the skill of thinking.

-

Other principles are concerned with the practical use of that skill.

-

It is worth reviewing these principles from time to time.

Constructive Thinking

Making things happen.

Proposals and suggestions.

Imagine eight brilliant critical thinkers sitting around a table to consider means to improve the town’s water supply.

None of those brilliant minds can get started until someone puts forward a proposal.

Now the full brilliance of that critical training can be unleashed.

But where does the proposal come from?

Who has been trained to put forward the proposal?

Critical thinking is a very important part of thinking, but it is by no means sufficient.

What I so strongly object to is the notion that it is enough to train critical minds.

This has been the tradition of Western thinking and it is inadequate.

Black hat thinking covers the aspect of critical thinking.

When dealing with the black thinking hat, I made it quite clear that a thinker wearing the black hat should play this role to the full: he or she should be as fiercely critical as possible.

This is an important part of thinking and it should be done well.

It is to yellow hat thinking that the constructive and generative aspect is left.

It is from yellow hat thinking that ideas, suggestions and proposals are to come.

We shall see later that the green hat (creativity) also plays an important role in designing new ideas.

Constructive thinking fits under the yellow hat because all constructive thinking is positive in attitude.

Proposals are made in order to make something better.

It may be a matter of solving a problem.

It may be a matter of making an improvement.

It may be a matter of using an opportunity.

In each case the proposal is designed to bring about some positive change.

One aspect of yellow hat thinking is concerned with reactive thinking.

This is the positive assessment aspect, which is the counterpart of the black hat negative assessment.

The yellow hat thinker picks out the positive aspects of an idea put before him or her just as the black hat thinker picks out the negative aspects.

In this section I am dealing with a different aspect of yellow hat thinking—the constructive aspect.

… To improve the water supply we could build a dam on the Elkin River, thereby creating a reservoir.

… There is abundant water in the mountains fifty miles away.

Would it be feasible to put in a pipeline?

… Normal flushing toilets use about eight gallons every time they are flushed.

There are new designs that use only one gallon.

That could save up to thirty gallons a day per person or nine million gallons a day.

… What about recycling the water?

I have heard there are new membrane methods that make it economical.

Also we would have less of a disposal problem.

Shall I look into this?

Each of these is a concrete suggestion.

Once a suggestion is on the table, then it can be developed further and eventually submitted to black hat assessment and yellow hat assessment.

… Put on your yellow hats and give me more concrete suggestions.

The more we have the better.

… John, what suggestion do you have?

How could we tackle this problem?

Get your yellow hat on.

Experts At this point someone would remark that proposals should come from the “water experts” and that it was not for amateurs to make such suggestions.

It would be the role of the amateurs with their critical thinking to assess the proposals put forward by the experts.

This is very much a political idiom.

The technicians are there to provide the ideas and the politician is there to assess them.

There may indeed be a role for this type of thinking in politics, but it does place the decision makers at the mercy of the experts.

In other areas, such as business or personal thinking, the thinker is his or her own expert and must produce the ideas.

Where do the suggestions and the proposals come from?

How does the yellow hat thinker come up with a solution?

There is no space in this book to go into the various methods of design and problem solving.

I have touched on these subjects in other books of mine.

The yellow hat proposals do not need to be special or very clever.

They might include routine ways of dealing with such matters.

They might include methods that are known to be used elsewhere.

They might include putting together some known effects in order to construct a particular solution.

Once the yellow hat has directed the thinker’s mind toward coming up with a proposal, the proposal itself may not be hard to find.

… Take off your black hat.

Instead of assessing the proposals we have so far, put on your yellow hat and give us some more proposals.

… Keeping my yellow hat on, I suggest that we let private enterprise sell water at competitive prices.

… No, we are not ready to switch into black hat thinking.

I do not believe we have exhausted all possible suggestions.

Yes, we do intend to bring in experts and consultants, but let us first establish some possible directions.

So it’s more yellow hat constructive thinking for the moment.

So yellow hat thinking is concerned with the generation of proposals and also with the positive assessment of the proposals.

Between these two aspects there is a third.

The third aspect is the developing or “building up” of a proposal.

This is much more than the reactive assessment of a proposal.

It is further construction.

The proposal is modified and improved and strengthened.

Under this improvement aspect of yellow hat thinking comes the correction of faults that have been picked out by black hat thinking.

As I made clear, black hat thinking can pick out the faults but has no responsibility for putting them right.

… If we hand over the water supply to private enterprise, there is a danger of the town being held to ransom by a monopoly supplier who establishes whatever price he likes.

… We could guard against that by putting a ceiling on the price.

This would be related to today’s pricing with an allowance for inflation.

I want to emphasize that no special cleverness is required by this constructive thinking aspect of the yellow hat.

It is just the desire to put forward concrete proposals even if they are very ordinary.

|

![]()

![]()