Information Challenges

About Peter Drucker

Amazon Link: Management Challenges for the 21st Century

See about management

Quoted (with color emphasis added for additional—beyond the all caps in the original text—concept highlighting) from the first few paragraphs of Chapter 4 of Peter Drucker's Management Challenges for the 21st Century

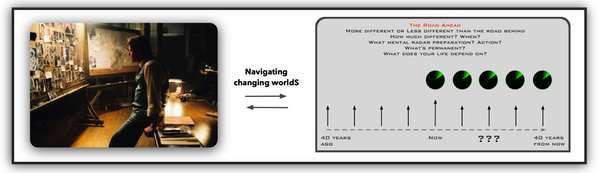

This is an example of a capital expenditure clue plus the work investments needed to acquire a new way of seeing our world (foresight) and some hindsight on unimagined futures.

Are you already working on this?

Who will need to understand this 15 years from now so they will be working on it?

Does this have a place in your strategic work plan?

Intelligence Information Thinking

Introduction—The New Information Revolution

A new Information Revolution is well under way.

It has started in business enterprise, and with business information.

But it will surely engulf ALL institutions of society.

It will radically change the MEANING of information for both enterprises and individuals.

It is not a revolution in technology, machinery, techniques, software or speed.

It is a revolution in CONCEPTS.

It is not happening in Information Technology (IT), or in Management Information Systems (MIS), and is not being led by Chief Information Officers (CIOs).

It is led by people on whom the Information Industry tends to look down: accountants.

But an Information Revolution has also been going on in information for the individual.

Again it is not happening in IT or MIS, and is not led by CIOs.

It is a print revolution. And what has triggered these information revolutions and is driving them is the failure of the “Information Industry”—the IT people, the MIS people, the CIOs—to provide INFORMATION.

So far, for fifty years, Information Technology has centered on DATA—their collection, storage, transmission, presentation.

It has focused on the “T” in “IT.”

The new information revolutions focus on the “I”

They ask, “What is the MEANING of information and its PURPOSE?”

And this is leading rapidly to redefining the tasks to be done with the help of information and, with it, to redefining the institutions that do these tasks.

From the “T” to the “I” in “IT”

A half century ago, around 1950, prevailing opinion overwhelmingly held that the market for that new “miracle,” the computer, would be in the military and in scientific calculations, for example, astronomy.

A few of us, however—a very few indeed—argued even then that the computer would find major applications in business and would have an impact on it.

These few also foresaw—again very much at odds with the prevailing opinion (even of practically everyone at IBM, just then beginning its ascent)—that in business the computer would be more than a very fast adding machine doing clerical chores such as payroll or telephone bills.

On specifics, we dissenters disagreed, of course, as “experts” always do.

But all of us nonconformists agreed on one thing: The computer would, in short order, revolutionize the work of top management.

It would, we all agreed, have its greatest and earliest impacts on business policy, business strategy and business decisions.

We could not have been more wrong.

The revolutionary impacts so far have been where none of us then anticipated them: on OPERATIONS.

Not one of us, for instance, could have imagined the truly revolutionary software now available to architects.

At a fraction of traditional cost and time, it designs the “innards” of large buildings: their water supply and plumbing; their lighting, heating and air-conditioning; their elevator specifications and placement-work that even a few years ago still absorbed some two-thirds of the time and cost of designing an office building, a large school, a hospital or a prison.

Not one of us could then have imagined the equally revolutionary software available to today’s surgical residents.

It enables them to do “virtual operations” whose outcomes include “virtually killing” patients if the resident makes the wrong surgical move.

Until recently, residents rarely even saw much of an operation before the very end of their training.

Half a century ago no one could have imagined the software that enables a major equipment maker such as Caterpillar to organize its operations, including manufacturing worldwide, around the anticipated service and replacement needs of its customers.

And the computer has had a similar impact on bank operations, with banking probably the most computerized industry today.

But the computer and the information technology arising from it have so far had practically no impact on the decision whether or not to build a new office building, a school, a hospital or a prison, or on what its function should or could be.

They have had practically no impact on the decision to perform surgery on a critically sick patient or on what surgery to perform.

They have had no impact on the decision of the equipment manufacturer concerning which markets to enter and with which products, or on the decision of a major bank to acquire another major bank.

For top management tasks, information technology so far has been a producer of data rather than a producer of information let alone a producer of new and different questions and new and different strategies.

The people in Management Information Systems (MIS) and in Information Technology (IT) tend to blame this failure on what they call the “reactionary” executives of the “old school.”

It is the wrong explanation.

Top executives have not used the new technology because it has not provided the information they need for their own tasks.

The data available in business enterprise are, for instance, still largely based on the early- 19th-century theorem that lower costs differentiate businesses and make them compete successfully.

MIS has taken the data based on this theorem and computerized them.

They are the data of the traditional accounting system.

Accounting was originally created, at least five hundred years ago, to provide the data a company needed for the preservation of its assets and for their distribution if the venture were liquidated.

And the one major addition to accounting since the 15th century—cost accounting, a child of the 1920s—aimed only at bringing the accounting system up to 19th-century economics, namely, to provide information about, and control of costs.

(So does, by the way, the now so-popular revision of cost accounting: total quality management.)

But, as we began to realize around the time of World War II, neither preservation of assets nor cost control is a top management task. They are OPERATIONAL TASKS.

A serious cost disadvantage may indeed destroy a business.

But business success is based on something totally different, the creation of value and wealth.

This requires risk-taking decisions:

1) on the theory of the business;

2) on business strategy;

3) on abandoning the old and innovating the new;

4) on the balance between immediate profitability and market share.

These links need to point to something better — bobembry

It requires strategic decisions based on the New Certainties discussed in Chapter Two.

These decisions are the true top management tasks.

It was this recognition that underlay, after World War II, the emergence of management as a discipline, separate and distinct from what was then called business economics and is now called microeconomics.

But for none of these top management tasks does the traditional accounting system provide information.

Indeed, none of these tasks is even compatible with the assumptions of the traditional accounting model.

The new information technology, based on the computer, had no choice but to depend on the accounting system’s data.

No others were available.

It collected these data, systematized them, manipulated them, analyzed them and presented them.

On this rested, in large measure, the tremendous impact the new technology had on what cost accounting data were designed for: operations.

But it also explains information technology’s near-zero impact on the management of business itself.

Top management’s frustration with the data that information technology has so far provided has triggered the new, the next, Information Revolution.

Information technologists, especially chief information officers in businesses, soon realized that the accounting data are not what their associates need—which largely explains why MIS and IT people tend to be contemptuous of accounting and accountants.

But they did not, as a rule, realize that what was needed was not more data, more technology, more speed.

What was needed was to define information; what was needed was new concepts.

And in one enterprise after another, top management people during the last few years have begun to ask,

“What information concepts do we need for our tasks?”

And they have now begun to demand them of their traditional information providers, the accounting people.

The new accounting that is evolving as a result of these questions will be discussed in a later section of this chapter (“The Information Enterprises Need”).

And so is the one new area—and the most important one—in which we do not as yet have systemtic and organized methods for obtaining information: information on the OUTSIDE of the enterprise.

These new methods are very different in their assumptions and their origins.

Each was developed independently and by different people.

But they all have two things in common.

They aim at providing information rather than data. And they are designed for top management and to provide information for top management tasks and top management decisions.

The new Information Revolution began in business and has gone farthest in it.

But it is about to revolutionize education and health care.

Again, the changes in concepts will in the end be at least as important as the changes in tools and technology.

It is generally accepted now that education technology is due for profound changes and that with them will come profound changes in structure.

Long-distance learning, for instance, may well make obsolete within twenty-five years that uniquely American institution, the freestanding undergraduate college.

It is becoming clearer every day that these technical changes will—indeed must—lead to redefining what is meant by education.

One probable consequence: The center of gravity in higher education (i.e., post-secondary teaching and learning) may shift to the continuing professional education of adults during their entire working lives.

This, in turn, is likely to move learning off campus and into a lot of new places: the home, the car or the commuter train, the workplace, the church basement or the school auditorium where small groups can meet after hours.

See this

In health care a similar conceptual shift is likely to lead from health care being defined as the fight against disease to being defined as the maintenance of physical and mental functioning.

The fight against disease remains an important part of medical care, of course, but as what a logician would call a subset of it.

Neither of the traditional health care providers, the hospital and the general practice physician, may survive this change, and certainly not in their present form and function.

Find “hospital” here

In education and health care, the emphasis thus will also shift from the “T” in IT to the “I,” as it is shifting in business.

The ability to interpret and process information

Information Challenges — full text

Introduction: The New Information Revolution

A new Information Revolution is well under way.

It has started in business enterprise, and with business information.

But it will surely engulf ALL institutions of society.

It will radically change the MEANING of information for both enterprises and individuals.

It is not a revolution in technology, machinery, techniques, software or speed.

It is a revolution in CONCEPTS.

It is not happening in Information Technology (IT), or in Management Information Systems (MIS), and is not being led by Chief Information Officers (CIOs).

It is led by people on whom the Information Industry tends to look down: accountants.

But an Information Revolution has also been going on in information for the individual.

Again it is not happening in IT or MIS, and is not led by CIOs.

It is a print revolution.

And what has triggered these information revolutions and is driving them is the failure of the “Information Industry”—the IT people, the MIS people, the CIOs—to provide INFORMATION.

So far, for fifty years, Information Technology has centered on DATA—their collection, storage, transmission, presentation.

It has focused on the “T” in “IT.”

The new information revolutions focus on the “I.”

They ask, “What is the MEANING of information and its PURPOSE?”

And this is leading rapidly to redefining the tasks to be done with the help of information and, with it, to redefining the institutions that do these tasks.

From the “T” to the “I” in “IT”

A half century ago, around 1950, prevailing opinion overwhelmingly held that the market for that new “miracle,” the computer, would be in the military and in scientific calculations, for example, astronomy.

A few of us, however—a very few indeed—argued even then that the computer would find major applications in business and would have an impact on it.

These few also foresaw—again very much at odds with the prevailing opinion (even of practically everyone at IBM, just then beginning its ascent)—that in business the computer would be more than a very fast adding machine doing clerical chores such as payroll or telephone bills.

On specifics, we dissenters disagreed, of course, as “experts” always do.

But all of us nonconformists agreed on one thing: The computer would, in short order, revolutionize the work of top management.

It would, we all agreed, have its greatest and earliest impacts on business policy, business strategy and business decisions.

We could not have been more wrong.

The revolutionary impacts so far have been where none of us then anticipated them: on OPERATIONS.

Not one of us, for instance, could have imagined the truly revolutionary software now available to architects.

At a fraction of traditional cost and time, it designs the “innards” of large buildings: their water supply and plumbing; their lighting, heating and air-conditioning; their elevator specifications and placement-work that even a few years ago still absorbed some two-thirds of the time and cost of designing an office building, a large school, a hospital or a prison.

Not one of us could then have imagined the equally revolutionary software available to today’s surgical residents.

It enables them to do “virtual operations” whose outcomes include “virtually killing” patients if the resident makes the wrong surgical move.

Until recently, residents rarely even saw much of an operation before the very end of their training.

Half a century ago no one could have imagined the software that enables a major equipment maker such as Caterpillar to organize its operations, including manufacturing worldwide, around the anticipated service and replacement needs of its customers.

And the computer has had a similar impact on bank operations, with banking probably the most computerized industry today.

But the computer and the information technology arising from it have so far had practically no impact on the decision whether or not to build a new office building, a school, a hospital or a prison, or on what its function should or could be.

They have had practically no impact on the decision to perform surgery on a critically sick patient or on what surgery to perform.

They have had no impact on the decision of the equipment manufacturer concerning which markets to enter and with which products, or on the decision of a major bank to acquire another major bank.

For top management tasks, information technology so far has been a producer of data rather than a producer of information let alone a producer of new and different questions and new and different strategies.

The people in Management Information Systems (MIS) and in Information Technology (IT) tend to blame this failure on what they call the “reactionary” executives of the “old school.”

It is the wrong explanation.

Top executives have not used the new technology because it has not provided the information they need for their own tasks.

The data available in business enterprise are, for instance, still largely based on the early- 19th-century theorem that lower costs differentiate businesses and make them compete successfully.

MIS has taken the data based on this theorem and computerized them.

They are the data of the traditional accounting system.

Accounting was originally created, at least five hundred years ago, to provide the data a company needed for the preservation of its assets and for their distribution if the venture were liquidated.

And the one major addition to accounting since the 15th century-cost accounting, a child of the 1920s—aimed only at bringing the accounting system up to 19th-century economics, namely, to provide information about, and control of, costs.

(So does, by the way, the now—so-popular revision of cost accounting: total quality management.)

But, as we began to realize around the time of World War II, neither preservation of assets nor cost control is a top management task.

They are OPERATIONAL TASKS.

A serious cost disadvantage may indeed destroy a business.

But business success is based on something totally different, the creation of value and wealth.

This requires risk-taking decisions: on the theory of the business, on business strategy, on abandoning the old and innovating the new, on the balance between immediate profitability and market share.

It requires strategic decisions based on the New Certainties discussed in Chapter Two.

These decisions are the true top management tasks.

It was this recognition that underlay, after World War II, the emergence of management as a discipline, separate and distinct from what was then called business economics and is now called microeconomics.

But for none of these top management tasks does the traditional accounting system provide information.

Indeed, none of these tasks is even compatible with the assumptions of the traditional accounting model.

The new information technology, based on the computer, had no choice but to depend on the accounting system’s data.

No others were available.

It collected these data, systematized them, manipulated them, analyzed them and presented them.

On this rested, in large measure, the tremendous impact the new technology had on what cost accounting data were designed for: operations.

But it also explains information technology’s near-zero impact on the management of business itself.

Top management’s frustration with the data that information technology has so far provided has triggered the new, the next, Information Revolution.

Information technologists, especially chief information officers in businesses, soon realized that the accounting, data are not what their associates need—which largely explains why MIS and IT people tend to be contemptuous of accounting and accountants.

But they did not, as a rule, realize that what was needed was not more data, more technology, more speed.

What was needed was to define information; what was needed was new concepts.

And in one enterprise after another, top management people during the last few years have begun to ask,

“What information concepts do we need for our tasks?”

And they have now begun to demand them of their traditional information providers, the accounting people.

The new accounting that is evolving as a result of these questions will be discussed in a later section of this chapter (“The Information Enterprises Need”).

And so is the one new area—and he most important one—in which we do not as yet have systematic and organized methods for obtaining information: information on the OUTSIDE of the enterprise.

These new methods are very different in their assumptions and their origins.

Each was developed independently and by different people.

But they all have two things in common.

They aim at providing information rather than data.

And they are designed for top management and to provide information for top management tasks and top management decisions.

The new Information Revolution began in business and has gone farthest in it.

But it is about to revolutionize education and health care.

Again, the changes in concepts will in the end be at least as important as the changes in tools and technology.

It is generally accepted now that education technology is due for profound changes and that with them will come profound changes in structure.

Long-distance learning, for instance, may well make obsolete within twenty-five years that uniquely American institution, the freestanding undergraduate college.

It is becoming clearer every day that these technical changes will—indeed must—lead to redefining what is meant by education.

One probable consequence: The center of gravity in higher education (i.e., post-secondary teaching and learning) may shift to the continuing professional education of adults during their entire working lives.

This, in turn, is likely to move learning off campus and into a lot of new places: the home, the car or the commuter train, the workplace, the church basement or the school auditorium where small groups can meet after hours.

In health care a similar conceptual shift is likely to lead from health care being defined as the fight against disease to being defined as the maintenance of physical and mental functioning.

The fight against disease remains an important part of medical care, of course, but as what a logician would call a subset of it.

Neither of the traditional health care providers, the hospital and the general practice physician, may survive this change, and certainly not in their present form and function.

In education and health care, the emphasis thus will also shift from the “T” in IT to the “I,” as it is shifting in business.

The Lessons of History

The current Information Revolution is actually the fourth Information Revolution in human history.

The first one was the invention of writing five thousand to six thousand years ago in Mesopotamia; then independently but several thousand years later—in China; and some fifteen hundred years later still, by the Maya in Central America.

The second Information Revolution was brought on by the invention of the written book, first in China, perhaps as early as 1300 B.C., and then, independently, eight hundred years later, in Greece, when Peisistratos, the tyrant of Athens, had Homer’s epics—only recited until then—copied into books.

The third Information Revolution was set off by Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press and of movable type between 145O and 1455, and by the contemporaneous invention of engraving.

We have almost no documents on the first two of these revolutions, though we know that the impact of the written book was enormous in Greece and Rome as well as in China.

In fact, China’s entire civilization and system of government still rest on it.

But on the third Information Revolution, printing and engraving, we have abundant material.

Is there anything we can learn today from what happened five hundred years ago?

The first thing to learn is a little humility.

Everybody today believes that the present Information Revolution is unprecedented in reducing the cost of, and in the spreading of, information—whether measured by the cost of a “byte” or by computer ownership—and in the speed and sweep of its impact.

These beliefs are simply nonsense.

At the time Gutenberg introduced the press, there was a substantial information industry in Europe.

it was probably Europe’s biggest employer.

It consisted of hundreds of monasteries, many of which housed large numbers of highly skilled monks.

Each monk labored from dawn to dusk, six days a week, copying books by hand.

An industrious, well-trained monk could do four pages a day, or twenty-five pages during a six-day week, for an annual output of twelve hundred to thirteen hundred handwritten pages.

Fifty years later, by 1500, the monks had become unemployed.

These monks (some estimates go well above ten thousand for all of Europe) had been replaced by a very small number of lay craftsmen, the new “printers,” totaling perhaps one thousand, but spread over all of Europe (though only beginning to establish themselves in Scandinavia).

To produce a printed book required coordinated teamwork by up to twenty such craftsmen, beginning with one highly skilled cutter of type, to a much larger number, maybe ten or more, of much less skilled bookbinders.

Such a team produced each year about twenty-five titles, with an average of two hundred pages per title, or five thousand pages ready to be printed.

By 1505, print runs of one thousand copies became possible.

This meant that a printing team could produce annually at least 5 million printed pages, bound into 25,000 books ready to be sold—or 250,000 pages per team member as against the twelve hundred or thirteen hundred the individual monk had produced only fifty years earlier.

Prices fell dramatically.

As late as the mid-1400s—just before Gutenberg’s invention—books were such a luxury that only the wealthy and educated could afford them.

But when Martin Luther’s German Bible came out in 1522 (a book of well over one thousand pages), its price was so low that even the poorest peasant family could buy one.

The cost and price reductions of the third Information Revolution were at least as great as those of the present, the fourth Information Revolution.

And so were the speed and the extent of its spread.

This has been just as true of every other major technological revolution.

Though cotton was by far the most desirable of all textile fibers—it is easily washable and can be worked up into an infinite variety of different cloths—it .required a time- and labor-expensive process.

It took twelve to fourteen man-days to produce a pound of cotton yarn by hand, as against one to two man-days for wool, two to five for linen and six for silk.

Between 1764, when machine tools to work cotton were first introduced—triggering the Industrial Revolution—and 1784, the time needed to produce a pound of cotton yarn fell to a few hours.

(This interval, incidentally, is exactly the same as that between the ENIAC and IBM’s 360.)

The price dropped by 70 percent and production rose twenty-fivefold.

Yet this was still before Eli Whitney’s cotton gin (1793), which produced a further fall in the price of cotton yarn of 90 percent plus and ultimately to about a thousandth of what it had been before the Industrial Revolution of fifty or sixty years earlier.

Just as important as the reduction in costs and the speed of the new printing technology was its impact on what information meant.

The first printed books, beginning with Gutenberg’s Bible, were in Latin and still had the same topics as the books that the monks had earlier written out by hand: religious and philosophical treatises and whatever texts had survived from Latin antiquity.

But only twenty years after Gutenberg’s invention, books by contemporary authors began to emerge, though they still appeared in Latin.

Another ten years and books were printed not only in Greek and Hebrew but also, increasingly, in the vernacular (first in English, then in the other European tongues).

And in 1476, only twenty years after Gutenberg, the English printer William Caxton (1422-1491) published a book on so worldly a subject as chess.

By 1500, popular literature no longer meant verse—epics, especially—that lent themselves to oral transmission, but prose, that is, the printed book.

In no time at all, the printing revolution also changed institutions, including the educational system.

In the decades that followed, university after university was founded throughout Europe, but unlike the earlier ones, they weren’t designed for the clergy or for the study of theology.

They were built around disciplines for the laity: law, medicine, mathematics, natural philosophy (science).

And eventually—though it took two hundred years—the printed book created universal education and the present school.

Printing’s greatest impact, however, was on the core of pre-Gutenberg Europe: the church.

Printing made the Protestant Reformation possible.

Its predecessors, the reformations of John Wycliffe in England (1330-1384) and of Jan Hus in Bohemia (1372-1415), had met with an equally enthusiastic popular response.

But those revolts could not travel farther or faster than the spoken word and could thus be localized and suppressed.

This was not the case when Luther, on October 31, 1517, nailed his ninety-five theses on a church door in an obscure German town.

He had intended only to initiate a traditional theological debate within the church.

But without Luther’s consent (and probably without his knowledge), the theses were immediately printed and distributed gratis all over Germany, and then all over Europe.

These printed leaflets ignited the religious firestorm that turned into the Reformation.

Would there have been an age of discovery, beginning in the second half of the 15th century, without the printing press?

Printing publicized every single advance the Portuguese seafarers made along the west coast of Africa in their search for a sea route to the Indies.

Printing provided Columbus with the first (though totally wrong) maps of the fabled lands beyond the western horizon, such as Marco Polo’s China and the legendary Japan.

Printing made it possible to record the results of every single voyage immediately and to create new, more reliable maps.

Noneconomic changes cannot be quantified.

But the impact on society, education, culture—let alone on religion—of the printing revolution was easily as great and surely as fast as the impact of the present Information Revolution, if not faster.

History’s Lesson for the Technologists

The last Information Revolution, the printed book, may also have a lesson for today’s information technologists, the IT and MIS people and the CI0s: They will not disappear.

But they may be about to become “Supporting Cast” rather than the “Superstars” they have been the last forty years.

The printing revolution immediately created a new class of information technologists, just as the most recent Information Revolution has created any number of information businesses, MIS and IT specialists, software designers and chief information officers.

The IT people of the printing revolution were the early printers.

Nonexistent—and indeed not even imaginable—in 1455, they had become stars twenty-five years later.

These virtuosi of the printing press were known and revered all over Europe, just as the names of the leading computer and software firms are recognized and admired worldwide today.

Printers were courted by kings, princes, the Pope and rich merchant cities and were showered with money and honors.

The first of these tycoons was the famous Venetian printer Aldus Manutius (1449-1515).

He realized that the new printing press could make a large number of impressions from the same plate—a thousand by the year 1505.

He created the low-cost, mass-produced book.

Aldus Manutius created the printing industry: He was the first to extend printing to languages other than Latin and also the first to do books by contemporary authors.

Altogether his press turned out well over one thousand titles.

The last of these great printing technologists, and also the last of the printing princes, was Christophe Plantin (l520-1589) of Antwerp.

Starting as a humble apprentice binder, he built Europe’s biggest and most famous printing firm.

By marrying the two new technologies, printing and engraving, he created the illustrated book.

He became Antwerp’s leading patrician (Antwerp was then one of the richest cities in Europe, if not the world), and he became so wealthy that he was able to build himself a magnificent palace, still preserved today as a printing museum.

But Plantin and his printing house began to decline well before his death and soon faded into insignificance.

By 1580 or so, the printers, with their focus on technology, had become ordinary craftsmen, respectable tradesmen to be sure, but definitely no longer of the upper class.

And they had also ceased both to be more profitable than other trades and to attract investment capital.

Their place was soon taken by what we now call publishers (though the term wasn’t coined until much later), people and firms whose focus was no longer on the “T” in IT but on the “I.”

This shift got under way the moment the new technology began to have an impact on the MEANING of information, and with it, on the meaning and function of the 15th century’s key institutions such as the church and the universities.

It thus began at the same juncture at which we now find ourselves in the present Information Revolution.

Is this where Information Technology and Information Technologists are now?

The New Print Revolution

There is actually no reason to believe that the new Information Revolution has to be “high-tech” at all.

For we did have a real “Information Revolution” these last fifty years, from 1950 on.

But it is not based on computers and electronics.

The real boom and it has been a veritable boom—has been in that old “no-tech” medium, PRINT.

In 1950 when television first swept the country, it was widely believed that it would be the end of the printed book.

U.S. population since has grown by two-thirds.

The number of college and university students—the most concentrated group of users and buyers of books—has increased five-fold.

But the number of printed books published and bought in the U.S. has grown at least fifteen-fold, and probably closer to twenty-fold.

It is generally believed that the leading “high-tech” companies IBM in the sixties and seventies, Microsoft since 1980—have been the fastest-growing businesses in the post-World War II period.

But the world’s two leading print companies have grown at least as fast.

One is the German-based Bertelsmann Group.

A small publisher of Protestant prayer books before Hitler, Bertelsmann was suppressed by the Nazis.

It was revived after World War II by the founder’s grandson, Reinhard Mohn.

Still privately held, Bertelsmann publishes no sales or profit figures.

But it is now the world’s number one publisher and distributor of printed materials (other than daily papers) in most countries of the world (except in China and Russia), through its ownership of publishing firms (e.g., of Random House in the United States), of book clubs and of magazines (e.g., of France’s leading business magazine Capital).

Equally fast has been the growth of the empire of the Australian-born Rupert Murdoch.

Starting as publisher of two small provincial Australian daily papers, Murdoch now owns newspapers throughout the English speaking world, leading English-language book publishers and magazines—but also a large company in another precomputer “information medium,” the movies.

Even faster than the growth of these BOOK publishers has been the growth of another PRINT medium: the “specialty mass magazine.”

A good many of the huge-circulation “general magazines)) that dominated 1920s and 1930s America, Life, for instance, or The Saturday Evening Post, have disappeared.

They did indeed fall victim to television.

But there are in the United States now several THOUSAND—one estimate is more than THREE THOUSAND—specialty mass magazines, each with a circulation between fifty thousand and a million, and most highly profitable.

The most visible examples are magazines that cover business or the economy.

The three leading American magazines of this type, Business Week (a weekly), Fortune (a biweekly), and Forbes (a monthly), each have a circulation approaching 1 million.

Before World War II the London—based Economist—the world’s only magazine that systematically reports every week on economics, politics and business all the world over—was practically unknown outside the UK, and even there its circulation was quite small, well below one hundred thousand copies.

Now its U.S. circulation alone exceeds three hundred thousand copies a week.

But there are similar specialty mass-circulation magazines in every field and for every interest—in health care and in running symphony orchestras, in psychology and in foreign affairs, in architecture and home maintenance and computers and, above all, for every single profession, every single trade, every single industry.

One of the most successful—and one of the earliest ones—is Scientific American, a U.S. monthly founded (or rather refounded) in the late 1940s, in which distinguished scientists explain their own specialized scientific area to the “scientific laity,” that is, to scientists in other specialties.

And what explains the success of the PRINT media?

College students probably account for the largest single share of the growth of printed books in the United States.

It is growth in college texts and in books assigned by college teachers.

But the second largest group are books that did not exist before the 1950s, at least not in any quantity.

There is no English word for them.

But the German publisher who first saw their potential and first founded a publishing house expressly to publish such books, the late E.B. von Wehrenalp (who founded Econ Verlag in Duesseldorf—still my German publisher), called it the Sachbucb—a book written by an expert for nonexperts.

And when asked to explain the Sachbuch Wehrenalp said:

“It has to be enjoyable reading.

It has to be educational.

But its purpose is neither entertainment nor education.

Its purpose is INFORMATION.”

This is just as true of the specialty mass magazines—whether written for the layman who wants to know about medicine or for the plumber who wants to know what goes on in the plumbing business.

THEY INFORM.

And above all, they inform about the OUTSIDE.

The specialty mass magazine tells the reader in a profession, a trade, an industry what goes on outside his or her own business, shop or office—about the competition, about new products and new technology, about developments in other countries and above all, about people in the profession, the trade, the industry (and gossip has always had the highest information—or misinformation—quotient of all communication).

And now the printed media are taking over the electronic channels.

The fastest-growing book seller since Aldus Manutius five hundred years ago has been Amazon.com, which sells printed books over the Internet.

In a few very short years it may have become the Internet’s largest retail merchant.

And Bertelsmann, in the fall of 1998, bought a controlling 50 percent in Barnes & Noble, Amazon’s main competitor.

More and more of the specialty mass magazines now publish an “on-line” edition—delivered over the Internet to be printed out by the subscriber.

Instead of IT replacing print, print is taking over the electronic technology as a distribution channel for PRINTED INFORMATION.

The new distribution channel will surely change the printed book.

New distribution channels always do change what they distribute.

But however delivered or stored, it will remain a printed product.

And it will still provide information.

The market for information exists, in other words.

And, though still disorganized, so does the supply.

In the next few years—surely not much more than a decade or two—the two will converge.

And that will be the REAL NEW INFORMATION REVOLUTION—led not by IT people, but by accountants and publishers.

And then both enterprises and individuals will have to learn what information they need and how to get it.

THEY WILL HAVE TO LEARN TO ORGANIZE INFORMATION AS THEIR KEY RESOURCE.

The Information Enterprises Need

We are just beginning to understand how to use information as a tool.

But we already can outline the major parts of the information system enterprises need.

In turn, we can begin to understand the concepts likely to underlie the enterprise that executives will have to manage tomorrow.

From Cost Accounting to Result Control

We may have gone furthest in redesigning both enterprise and information in the most traditional of our information systems: accounting.

In fact, many businesses have already shifted from traditional cost accounting to activity-based costing.

It was first developed for manufacturing where it is now in wide use.

But it is rapidly spreading to service businesses and even to nonbusinesses, for example, universities.

Activity-based costing represents both a different concept of the business process and different ways of measuring.

Traditional cost accounting, first developed by General Motors seventy years ago, postulates that total manufacturing cost is the sum of the costs of individual operations.

Yet the cost that matters for competitiveness and profitability is the cost of the total process, and that is what the new activity based costing records and makes manageable.

Its basic premise is that business is an integrated process that starts when supplies, materials and parts arrive at the plant’s loading dock and continues even after the finished product reaches the end-user.

Service is still a cost of the product, and so is installation, even if the customer pays.

Traditional cost accounting measures what it costs to do something, for example, to cut a screw thread.

Activity-based costing also records the cost of not doing, such as the cost of machine downtime, the cost of waiting for a needed part or tool, the cost of inventory waiting to be shipped and the cost of reworking or scrapping a defective part.

The costs of not doing, which traditional cost accounting cannot and does not record, often equal and sometimes even exceed the cost of doing, Activity-based costing therefore gives not only much better cost control; increasingly, it gives result control.

Traditional cost accounting assumes that a certain operation—for example, heat treating—has to be done and that it has to be done where it is being done now.

Activity-based costing asks, “Does it have to be done?

If so, where is it best done?”

Activity based costing integrates what were once several procedures value analysis, process analysis, quality management and costing—into one analysis.

Using that approach, activity-based costing can substantially lower manufacturing costs—in some instances by a full third.

Its greatest impact, however, is likely to be in services.

In most manufacturing companies, cost accounting is inadequate.

But service industries—banks, retail stores, hospitals, schools, newspapers and radio and television stations—have practically no cost information at all.

Activity-based costing shows why traditional cost accounting has not worked for service companies.

It is not because the techniques are wrong.

It is because traditional cost accounting makes the wrong assumptions.

Service companies cannot start with the cost of individual operations, as manufacturing companies have done with traditional cost accounting.

They must start with the assumption that there is only one cost: that of the total system.

And it is a fixed cost over any given time period.

The famous distinction between fixed and variable costs, on which traditional cost accounting is based, does not make sense in services.

Neither does another basic assumption of traditional cost accounting: that capital can be substituted for labor.

In fact, in knowledge-based work especially, additional capital investment is likely to require more rather than less labor.

A hospital that buys a new diagnostic tool will not lay off anybody as a result.

But it will have to add four or five people to run the new equipment.

Other knowledge-based organizations have had to learn the same lesson.

But that all costs are fixed over a given time period and that resources cannot be substituted for each other are precisely the assumptions with which activity-based costing starts.

By applying them to services, we are beginning for the first time to get cost information and control.

Banks, for instance, have been trying for several decades to apply conventional cost-accounting techniques to their business—that is, to figure the costs of individual operations and services—with almost negligible results.

Now they are beginning to ask, “Which one activity is at the center of costs and of results?”

One answer: the customer.

The cost per customer in any major area of banking is a fixed cost.

Thus it is the yield per customer—both the volume of services a customer uses and the mix of those services that determines costs and profitability.

Retail discounters, especially those in Western Europe, have known that for some time.

They assume that once shelf space is installed, its cost is fixed, and management consists of maximizing the yield on the space over a given time span.

This focus on result control has enabled these discounters to increase profitability despite their low prices and low margins.

In some areas, such as research labs, where productivity is difficult to measure, we may always have to rely on assessment and judgment rather than on costing.

But for most knowledge-based and service work, we should, within ten years, have developed reliable tools to measure and manage costs and to relate those costs to results.

Thinking more clearly about costing in services should yield new insights into the costs of getting and keeping customers in businesses of all kinds.

If GM, Ford and Chrysler in the United States had used activity-based costing, for example, they would have realized early on the utter futility of their competitive “blitzes” of the past twenty years, which offered new-car buyers spectacular discounts and hefty cash rewards.

Those promotions actually cost the Big Three automakers enormous amounts of money and, worse, enormous numbers of customers.

In fact, every one resulted in a nasty drop in market standing.

But neither the costs of the special deals nor their negative yields appeared in the companies’ conventional cost-accounting figures, so management never saw the damage.

Because the Japanese used a form of activity-based costing—though a fairly primitive one—Toyota, Nissan and Honda knew better than to compete with the U.S. automakers through discount blitzes, and thus maintained both their market share and their profits.

From Legal Fiction to Economic Reality

Knowing the cost of operations, however, is not enough.

To compete successfully in an increasingly competitive global market, a company has to know the costs of its entire economic chain and has to work with other members of the chain to manage costs and maximize yield.

Companies are therefore beginning to shift from costing only what goes on inside their own organizations to costing the entire economic process, in which even the biggest company is just one link.

The legal entity, the company, is a reality for shareholders, for creditors, for employees, and for tax collectors.

But economically, it is fiction.

Thirty years ago the Coca-Cola Company was a franchiser all over the world.

Independent bottlers manufactured the product.

Now the company owns most of its bottling operations in the United States.

But Coke drinkers—even those few who know that fact—could not care less.

What matters in the marketplace is the economic reality, the costs of the entire process, regardless of who owns what.

Again and again in business history, an unknown company has come from nowhere and in a few short years has overtaken the established leaders without apparently even breathing hard.

The explanation always given is superior strategy, superior technology, superior marketing, or lean manufacturing.

But in every single case, the newcomer also enjoys a tremendous cost advantage, usually about 30 percent.

The reason is always the same: the new company knows and manages the costs of the entire economic chain rather than its costs alone.

Toyota is perhaps the best-publicized example of a company that knows and manages the costs of its suppliers and distributors; they are all, of course, members of its Keiretsu.

Through that network, Toyota manages the total cost of making, distributing and servicing its cars as one cost stream, putting work where it costs the least and yields the most.

(On the history of the Keiretsu see Chapter One.)

Economists have known the importance of costing the entire economic chain since Alfred Marshall wrote about it in the late 1890s.

But most business people still consider it theoretical abstraction.

Increasingly, however, managing the economic cost chain will become a necessity.

Indeed, executives need to organize and manage not only the cost chain but also everything else especially corporate strategy and product planning—as one economic whole, regardless of the legal boundaries of individual companies.

A powerful force driving companies toward economic chain costing will be the shift from cost-led pricing to price-led costing.

Traditionally, Western companies have started with costs, put a desired profit margin on top, and arrived at a price.

They practiced cost-led pricing.

Sears and Marks & Spencer long ago switched to price-led costing, in which the price the customer is willing to pay determines allowable costs, beginning with the design stage.

Until recently, those companies were the exceptions.

Now price-led costing is becoming the rule.

The same ideas apply to outsourcing, alliances and joint ventures—indeed, to any structure that is built on partnership rather than control.

And such entities, rather than the traditional model of a parent company with wholly owned subsidiaries, are increasingly becoming the models for growth, especially in the global economy.

(On this see Chapter One.)

For many businesses it will be painful to switch to economic-chain costing.

Doing so requires uniform or at least compatible accounting systems of all companies along the entire chain.

Yet each one does its accounting in its own way, and each is convinced that its system is the only possible one.

Moreover, economic-chain costing requires information sharing across companies; yet even within the same company, people tend to resist information sharing.

Whatever the obstacles, economic-chain costing is going to be done.

Otherwise, even the most efficient company will suffer from an increasing cost disadvantage.

Information for Wealth Creation

Enterprises are paid to create wealth, not to control costs.

But that obvious fact is not reflected in traditional measurements.

First-year accounting students are taught that the balance sheet portrays the liquidation value of the enterprise and provides creditors with worst-case information.

But enterprises are not normally run to be liquidated.

They have to be managed as going concerns, that is, for wealth creation.

To do that requires four sets of diagnostic tools: foundation information, productivity information, competence information, and resource allocation information.

Together they constitute the executive’s tool kit for managing the current business.

Foundation Information

The oldest and most widely used set of diagnostic management tools are cash-flow and liquidity projections and such standard measurements as the ratio between dealers’ inventories and sales of new cars, the earnings coverage for interest payments on a bond issue, and the ratios between receivables outstanding more than six months, total receivables, and sales.

Those may be likened to the measurements a doctor takes at a routine physical: weight, pulse, temperature, blood pressure and urinalysis.

If those readings are normal, they do not tell us much.

If they are abnormal, they indicate a problem that needs to be identified and treated.

Those measurements might be called foundation information.

Productivity Information

The second set of tools for business diagnosis deals with the productivity of key resources.

The oldest of them—of World War II vintage—measures the productivity of manual labor.

Now we are slowly developing measurements though still quite primitive ones, for the productivity of knowledge-based and service work (see Chapter Five).

However, measuring only the productivity of workers, whether blue- or white-collar, no longer gives us adequate information about productivity.

We need data on total-factor productivity.

That explains the growing popularity of Economic Value Added Analysis (EVA).

It is based on something we have known for a long time: What we generally call profits, the money left to service equity, is not profit at all and may be mostly a genuine cost.

Until a business returns a profit that is greater than its cost of capital, it operates at a loss.

Never mind that it pays taxes as if it had a genuine profit.

The enterprise still returns less to the economy than it uses up in resources.

It does not cover its full costs unless the reported profit exceeds the cost of capital.

Until then, it does not create wealth; it destroys it.

By that measurement, incidentally, few U.S. businesses have been profitable since World War II.

By measuring the value added over all costs, including the cost of capital, EVA measures, in effect, the productivity of all factors of production.

It does not, by itself, tell us why a certain product or a certain service does not add value or what to do about it.

But it shows us what we need to find out and that we need to take action.

EVA should also be used to find out what works.

It does show which products, services, operations or activities have unusually high productivity and add unusually high value.

Then we should ask ourselves, “What can we learn from these successes?”

The most recent of the tools used to obtain productivity information is benchmarking—comparing one’s performance with the best performance in the industry or, better yet, with the best anywhere in the world.

Benchmarking assumes correctly that what one organization does, any other organization can do as well.

It assumes correctly that any business has to be globally competitive (see Chapter Two).

It assumes, also correctly, that being at least as good as the leader is a prerequisite to being competitive.

Together, EVA and benchmarking provide the diagnostic tools to measure total-factor productivity and to manage it.

Competence Information

A third set of tools deals with competences.

Leadership rests on being able to do something others cannot do at all or find difficult to do even poorly.

It rests on core competencies that meld market or customer value with a special ability of the producer or supplier.

Some examples: the ability of the Japanese to miniaturize electronic components, which is based on their three-hundred-year-old artistic tradition of putting landscape paintings on a tiny lacquered box, called an inro, and of carving a whole zoo of animals on the even tinier button, called a netsuke, that holds the box on the wearer’s belt; or the almost unique ability GM has had for eighty years to make successful acquisitions; or Marks & Spencer’s also unique ability to design packaged and ready-to-eat gourmet meals for middle-class purses.

But how does one identify both the core competencies one has already and those the business needs to take and maintain a leadership position?

How does one find out whether one’s core competence is improving or weakening?

Or whether it is still the right core competence and what changes it might need?

So far the discussion of core competencies has been largely anecdotal.

But a number of highly specialized, midsized companies—a Swedish pharmaceutical producer and a U.S. producer of specialty tools, to name two—are developing the methodology to measure and manage core competencies.

The first step is to keep careful track of one’s own and one’s competitors’ performance, looking especially for unexpected successes and for unexpected poor performance in areas where one should have done well.

The successes demonstrate what the market values and will pay for.

They indicate where the business enjoys a leadership advantage.

The nonsuccesses should be viewed as the first indication either that the market is changing or that the company’s competencies are weakening.

This analysis allows for the early recognition of opportunities.

By carefully tracking unexpected successes, a U.S. toolmaker found, for example, that small Japanese machine shops were buying its high-tech, high-priced tools, even though it had not designed the tools with them in mind or ever offered these tools to them.

That allowed the company to recognize a new core competence: its products were easy to maintain and to repair despite their technical complexity.

When that insight was applied to designing products, the company gained leadership in the small plant and machine-shop markets in the United States and Western Europe, huge markets where it had done practically no business before.

Core competencies are different for every organization; they are, so to speak, part of an organization’s personality.

But every organization—not just businesses—needs one core competence: innovation.

And every organization needs a way to record and appraise its innovative performance.

In organizations already doing that—among them several topflight pharmaceutical manufacturers—the starting point is not the company’s own performance.

It is a careful record of the innovations in the entire field during a given period.

Which of them were truly successful?

How many of them were ours?

Is our performance commensurate with our objectives?

With the direction of the market?

With our market standing?

With our research spending?

Are our successful innovations in the areas of greatest growth and opportunity?

How many of the truly important innovation opportunities did we miss?

Why?

Because we did not see them?

Or because we saw them but dismissed them?

Or because we botched them?

And how well do we do in converting an innovation into a commercial product?

A good deal of that, admittedly, is assessment rather than measurement.

It raises rather than answers questions, but it raises the right questions.

Resource Allocation Information

The last area in which diagnostic information is needed to manage the current business for wealth creation is the allocation of scarce resources: capital and performing people.

Those two convert into action all the information that a management has about its business.

They determine whether the enterprise will do well or poorly.

GM developed the first systematic capital-appropriations process about seventy years ago.

Today practically every business has a capital-appropriations process, but few use it correctly.

Companies typically measure their proposed capital appropriations by only one or two of the following yardsticks: return on investment, payback period, cash flow, or discounted present value.

But we have known for a long time—since the early 1930s—that none of those is the right method.

To understand a proposed investment, a company needs to look to all four.

Sixty years ago that would have required endless number-crunching.

Now a laptop computer can provide the data within a few minutes.

We also have known for sixty years that managers should never look at just one proposed capital appropriation in isolation but should instead choose the projects that show the best ratio between opportunity and risks.

That requires a capital appropriations budget to display the choices—again, something far too many businesses do not do.

Most serious, however, is that most capital-appropriations processes do not even ask for two vital pieces of information:

What will happen if the proposed investment fails to produce the promised results, as do three out of every five?

Would it seriously hurt the company, or would it be just a flea-bite?

If the investment is successful—and especially if it is more successful than we expect—what will it commit us to?

In addition, a capital-appropriations request requires specific deadlines: When should we expect what results?

Then the results—successes, near successes, near failures, and failures need to be reported and analyzed.

There is no better way to improve an organization’s performance than to measure the results of capital spending against the promises and expectations that led to its authorization.

Search book contents by Peter Drucker

How much better off would the United States be today had such feedback on government programs been standard practice for the past fifty years?

Capital, however, is only one key resource of the organization, and it is by no means the scarcest one.

The scarcest resources in any organization are performing people.

Since World War II, the U.S. military—and so far no one else—has learned to test its placement decisions.

It now thinks through what it expects of senior officers before it puts them into key commands.

It then appraises their performance against those expectations.

And it constantly appraises its own process for selecting senior commanders against the successes and failures of its appointments.

In business—but in universities, hospitals and government agencies as well—placement with specific expectations as to what the appointee should achieve and systematic appraisal of the outcome are virtually unknown.

In the effort to create wealth, managers need to allocate human resources as purposefully and as thoughtfully as they do capital.

And the outcomes of those decisions ought to be recorded and studied as carefully.

Where the Results Are

Those four kinds of information tell us only about the current business.

They inform and direct tactics.

For strategy, we need organized information about the environment.

Strategy has to be based on information about markets, customers and noncustomers; about technology in one’s own industry and others; about worldwide finance, and about the changing world economy.

For that is where the results are.

Inside an organization there are only cost centers.

The only profit center is a customer whose check has not bounced.

Major changes always start outside an organization.

A retailer may know a great deal about the people who shop at its stores.

But no matter how successful, no retailer ever has more than a small fraction of the market as its customers; the great majority are noncustomers.

It is always with noncustomers that basic changes begin and become significant.

At least half the important new technologies that have transformed an industry in the past fifty years came from outside the industry itself Commercial paper, which has revolutionized finance in the United States, did not originate with the banks.

Molecular biology and genetic engineering were not developed by the pharmaceutical industry.

Though the great majority of businesses will continue to operate only locally or regionally, they all face, at least potentially, global competition from places they have never even heard of before.

Not all of the needed information about the outside is available, to be sure, despite the specialty mass magazines.

There is no information—not even unreliable information—on economic conditions in most of China, for instance, or on legal conditions in the successor states to the Soviet empire.

But even where information is readily available, many businesses are oblivious to it.

Many U.S. companies went into Europe in the 1960s without even asking about labor legislation.

European companies have been just as blind and ill-informed in their ventures into the United States.

A major cause of the Japanese real estate investment debacle in California during the 1990s was the failure to find out elementary facts about zoning and taxes.

A serious cause of business failure is the common assumption that conditions—taxes, social legislation, market preferences, distribution channels, intellectual property rights and many others—must be what we think they are or at least what we think they should be.

An adequate information system has to include information that makes executives question that assumption.

It must lead them to ask the right questions, not just feed them the information they expect.

That presupposes first that executives know what information they need.

It demands further that they obtain that information on a regular basis.

It finally requires that they systematically integrate the information into their decision making.

These are beginnings.

These are first attempts to organize “Business Intelligence,” that is, information about actual and potential competitors worldwide.

A few multinationals—Unilever, Coca-Cola, Nestle, some Japanese trading companies, and a few big construction companies—have been working hard on building systems to gather and organize outside information.

But in general, the majority of enterprises have yet to start the job.

It is fast becoming the major information challenge for all enterprises.

III The Information Executives Need for Their Work

A great deal of the new technology has been data processing equipment for the individual.

But as far as information goes, the attention has been mainly on information for the enterprise—as it has been so far in this chapter.

But information for executives—and indeed, for all knowledge workers—for their own work may be a great deal more important.

For the knowledge worker in general, and especially for executives, information is their key resource.

Information increasingly creates the link to their fellow workers and to the organization, and their “network.”

It is information, in other words, that enables knowledge workers to do their job.

By now it is clear that no one can provide the information that knowledge workers and especially executives need, except knowledge workers and executives themselves.

But few executives so far have made much of an effort to decide what they need, and even less, how to organize it.

They have tended to rely on the producers of data—IT people and accountants—to make these decisions for them.

But the producers of data cannot possibly know what data the users need so that they become information.

Only individual knowledge workers, and especially individual executives, can convert data into information.

And only individual knowledge workers, and especially individual executives, can decide how to organize their information so that it becomes their key to effective action.

To produce the information executives need for their work, they have to begin with two questions:

“What information do I owe to the people with whom I work and on whom I depend?

In what form?

And in what time frame?”

“What information do I need myself?

From whom?

In what form?

And in what time frame?”

These two questions are closely connected.

But they are different.

What I owe comes first because it establishes communications.

And unless that has been established, there will be no information flow back to the executive.

We have known this since Chester I. Barnard (1886-1961) published his pioneering book The Functions of the Executive, in 1938, over sixty years ago.

Yet, while Barnard’s book is universally praised, it has had little practical impact.

Communication for Barnard was vague and general.

It was human relationships, and personal.

However, what makes communications effective at the workplace is that they are focused on something outside the person.

They have to be focused on a common task and on a common challenge.

They have to be focused on the work.

And by asking: “To whom do I owe information, so that they can do their work?”

communications are being focused on the common task and the common work.

They become effective.

The first question therefore (as in any effective relationship), is not: “What do I want and need?”

It is: “What do other people need from me?”

and “Who are these other people?”

Only then can the question be asked: “What information do I need?

From whom?

In what form?

In what time frame?”

Executives who ask these questions will soon find that little of the information they need comes out of their own company’s information system.

Some comes out of accounting—though in many cases the accounting data has to be rethought, reformulated, rearranged to apply to the executive’s own work.

But a good deal of the information executives need for their own work will come, as said already, from the outside and will have to be organized quite separately and distinctly from the inside information system.

The only one who can answer the question:

“What do I owe by way of information?

To whom?

In what form?”

is the other person.

The first step in obtaining the information that executives need for their own work is, therefore, to go to everyone with whom they work, everyone on whom they depend, everyone who needs to know what they themselves are doing, and ask them.

But before one asks, one has to be prepared to answer.

For the other person will—and should—come back and ask:

“And what information do you need from me?”

Hence, executives need first to think through both questions—but then they start out by going to the other people and ask them first to tell them: “What do I owe you?”

Both questions, “What do I owe?”

and “What do I need?”

sound deceptively simple.

But everyone who has asked them has soon found out that it takes a lot of thought, a lot of experimentation, a lot of hard work, to answer them.

And the answers are not forever.

In fact, these questions have to be asked again, every eighteen months or so.

They also have to be asked every time there is a real change, for example, a change in the enterprise’s theory of the business, in the individual’s own job and assignment, or in the jobs and assignments of the other people.

But if individuals ask these questions seriously, they will soon come to understand both what they need and what they owe.

And then they can set about organizing both.

Organizing Information

Unless organized, information is still data.

To be meaningful it has to be organized.

It is, however, not clear at all in what form certain kinds of information are meaningful, and especially in what form of organization they are meaningful for one’s own job.

And the same information may have to be organized in different ways for different purposes.

Here is one example.

Since Jack Welch took over as CEO in 1981, the General Electric Company (GE) has created more wealth than any other company in the world.

One of the main factors in this success was that GE organized the same information about the performance of every one of its business units differently for different purposes.

It kept traditional financial and marketing reporting, the way most companies appraise their businesses every year or so.

But the same data were also organized for long-range strategy, that is, to show unexpected successes and unexpected failures, but also to show where actual events differed substantially from what was expected.

A third way to organize the same data was to focus on the innovative performance of the business—which became a major factor in determining compensation and bonuses of the general manager and of the senior management people of a business unit.

Finally, the same data were organized to show how the business unit and its management treated and developed people—which then became a key factor in deciding on the promotion of an executive, and especially of the general manager of a business unit.

No two executives, in my experience, organize the same information the same way.

And information has to be organized the way individual executives work.

But there are some basic methodologies to organize information.

One is the Key Event.

Which events—for it is usually more than one—are the “hinges” on which the rest of my performance primarily depends?

The key event may be technological—the success of a research project.

it may have to do with people and their development.

It may have to do with establishing a new product or a new service with certain key customers.

It may be to obtain new customers.

What is a key event is very much the executive’s individual decision.

It is, however, a decision that needs to be discussed with the people on whom the executive depends.

It is perhaps the most important thing anybody in an organization has to get across to the people with whom one works, and especially to one’s own superior.

Another key methodological concept comes out of modern Probability Theory—it is the concept on which, for instance, Total Quality Management is based.

It is the difference between normal fluctuations within the range of normal probability distribution and the exceptional event.

As long as fluctuations stay within the normal distribution of probability for a given type of event (e.g., for quality in a manufacturing process), no action is taken.

Such fluctuations are data and not information.

But the exception, which falls outside the accepted probability distribution, is information.

It calls for action.

Another basic methodology for organizing information comes out of the theory of the Threshold Phenomenon—the theory that underlies Perception Psychology.

It was a German physicist, Gustav Fechner (1801-1887), who first realized that we do not feel a sensation—for example, a pin-prick until it reaches a certain intensity, that is, until it passes a perception threshold.

A great many phenomena follow the same law.

They are not actually “phenomena.”

They are data until they reach a certain intensity, and pass the perception threshold.

For many events, both in one’s work and in one’s personal life, this theory applies and enables one to organize data into information.

When we speak of a “recession” in the economy, we speak of a threshold phenomenon—a down turn in sales and profits is a recession when it passes a certain threshold, for example, when it continues beyond a certain length of time.

Similarly, a disease becomes an “epidemic’,, when, in a certain population, it passes and exceeds a certain threshold.

This concept is particularly useful to organize information about personnel events.

Such events as accidents, turnover, grievances, and so on become significant when they pass a certain threshold.

But the same is true of innovative performance in a company—except that there the perception threshold is the point below which a drop in innovative performance becomes relevant and calls for action.

The threshold concept is altogether one of the most useful concepts to determine when a sequence of events becomes a “trend,” and requires attention and probably action, and when events, even though they may look spectacular, are by themselves not particularly meaningful.

Finally, a good many executives have found that the one way of organizing information effectively is simply to organize one’s being informed about the unusual.

One example is the “manager’s letter.”

The people who work with a manager write a monthly letter to him or her, reporting on anything unusual and unexpected within their own sphere of work and action.

Most of these “unusual” things can safely be disregarded.

But again, and again, there is an “exceptional” event, one that is outside the normal range of probability distribution.

Again and again, there is a concatenation of events—insignificant in each reporter’s area, but significant if added together.

Again and again, the management letters bring out a pattern to which to pay attention.

Again and again, they convey information.

No Surprises

No system designed by knowledge workers, and especially by executives, to give them the information they need for their work will ever be perfect.

But, over the years, they steadily improve.

And the ultimate test of an information system is that there are no surprises.

Before events become significant, executives have already adjusted to them, analyzed them, understood them and taken appropriate action.