|

main brainroad continues ↓

But the center of gravity in the post-capitalist society—its structure, its social and economic dynamics, its social classes, and its social problems—is different from the one that dominated the last two hundred and fifty years and defined the issues around which political parties, social groups, social value systems, and personal and political commitments crystallized.

The basic economic resource—“the means of production,” to use the economist’s term—is no longer capital, nor natural resources (the economist’s “land”), nor “labor.”

It is and will be knowledge.

(but NOT education system courses)

The central wealth-creating activities

will be neither

the allocation of capital to productive uses,

nor “labor”—

the two poles of nineteenth- and twentieth-century economic theory,

whether classical, Marxist, Keynesian, or neo-classical.

Value is now created by “productivity” and “innovation,” both applications of knowledge to work.

The management revolution (below) ← ain’t what you assume

Knowledge: Its Economics and Its Productivity

Making the future

The manager and the moron — the thinking challenge

The leading social groups of the knowledge society will be “knowledge workers”—knowledge executives who know how to allocate knowledge to productive use just as the capitalists knew how to allocate capital to productive use; knowledge professionals; knowledge employees.

Practically all these knowledge people will be employed in organizations.

Yet, unlike the employees under Capitalism, they will own both the “means of production” and the “tools of production”—the former through their pension funds, which are rapidly emerging in all developed countries as the only real owners; the latter because knowledge workers own their knowledge and can take it with them wherever they go — a.k.a. mobility.

How does this alter economic dynamics?

The economic challenge of the post-capitalist society will therefore be the productivity of knowledge work and the knowledge worker — here, here and here.

sidebar

“Managing oneself is a REVOLUTION in human affairs.

It requires new and unprecedented things

from the individual, and especially

from the knowledge worker.

For, in effect, it demands that each

knowledge worker think and behave

as a chief executive officer.

It also requires an almost 180-degree change

in the knowledge workers’ thoughts and actions

from what most of us still

take for granted as the way to

think and the way to act.

The shift from manual workers

who do as they are being told — either

by the task or by the boss —

to knowledge workers

who have to manage themselves

profoundly challenges social structure.

For every existing society,

even the most “individualist” one,

takes two things for granted,

if only subconsciously:

Organizations outlive workers,

and most people stay put.

Managing oneself

is based on the very opposite realities.

In the United States MOBILITY is accepted.

But even in the United States,

workers outliving organizations — and with it

the need to be prepared for

a second and different half of one’s life —

is a revolution for which practically no one is prepared.

Nor is any existing institution,

for example, the present retirement system.”

Management Challenges for the 21st Century

The Daily Drucker for more career thoughts

main brainroad continues ↓

The social challenge of the post-capitalist society will, however, be the dignity of the second class in post-capitalist society: the service workers.

Service workers, as a rule, lack the necessary education to be knowledge workers.

And in every country, even the most highly advanced one, they will constitute a majority.

The post-capitalist society will be divided by a new dichotomy of values and of aesthetic perceptions.

It will not be the “Two Cultures”—literary and scientific—of which the English novelist, scientist, and government administrator C. P. Snow wrote in his The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution (1959), though that split is real enough.

The dichotomy will be between “intellectuals” and “managers,” the former concerned with words and ideas, the latter with people and work.

To transcend this dichotomy in a new synthesis will be a central philosophical and educational challenge for the post-capitalist society.

The memo THEY don’t want you to SEE

Outflanking the Nation-State

…

The nation-state is not going to wither away.

It may remain the most powerful political organ around for a long time to come, but it will no longer be the indispensable one.

Increasingly, it will share power with other organs, other institutions, other policy-makers.

What is to remain the domain of the nation-state?

What is to be carried out within the state by autonomous institutions?

How do we define “supranational” and “transnational"?

What should remain “separate and local"?

…

These questions will be central political issues for decades to come.

In its specifics, the outcome is quite unpredictable.

But the political order will look different from the political order of the last four centuries, in which the players differed in size, wealth, constitutional arrangements, and political creed, yet were uniform as nation-states—each sovereign within its territory and each defined by its territory.

We are moving—we have indeed already moved—into post-capitalist polity.

…

See Transnationalism, Regionalism, and Tribalism below

Money Knows No Fatherland …

… Nor Does Information

Money going transnational outflanks the nation-state by nullifying national economic policy.

Information going transnational outflanks the nation-state by undermining (in fact, destroying) the identification of “national” with “cultural” identity

Transnational Needs

Regionalism: the New Reality

The Return of Tribalism

Internationalism and regionalism challenge the sovereign nation-state from the outside.

Tribalism undermines it from within.

It saps the nation-state’s integrating power.

In fact, it threatens to replace nation with tribe.

The Need for Roots

The main reason for tribalism is neither politics nor economics.

It is existential.

People need roots in a transnational world; they need community.

They live increasingly in a transnational world.

But they feel the need for local roots; the need to belong to a local community.

Tribalism thrives precisely because people increasingly realize that what happens in Osaka affects people in Slovenia who have no idea where Osaka is and can hardly find it on the map.

Precisely because the world has become transnational in so many ways—and must become ever more so—people need to define themselves in terms they can understand.

The more transnational the world becomes, the more tribal it will also be.

This undermines the very foundations of the nation-state.

In fact, it ceases to be a “nation-state,” and becomes a “state” plain and simple, an administrative rather than a political unit.

Internationalism, regionalism, and tribalism between them are rapidly creating a new polity, a new and complex political structure, without precedent.

…

The last of what might be called the “pre-modern” philosophers, Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716), spent much of his life in a futile attempt to restore the unity of Christendom.

His motivation was not the fear of religious wars between Catholics and Protestants or between different Protestant sects; that danger had already passed when Leibniz was born.

He feared that without a common belief in a supernatural God, secular religions would emerge.

And a secular religion, he was convinced, would, almost by definition, have to be a tyranny and suppress the freedom of the person.

…

But surely the collapse of Marxism as a creed signifies the end of the belief in salvation by society.

…

What will emerge next, we cannot know; we can only hope and pray.

Perhaps nothing beyond stoic resignation?

The Third World

This book focuses on the developed countries: on Europe, the United States, and Canada, on Japan and the newly developed countries on the mainland of Asia, rather than on the developing countries of the “Third World.”

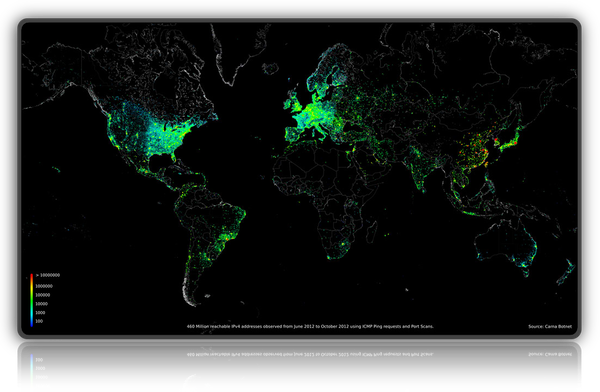

Internet activity ↓

…

But the developed countries also have a tremendous stake in the Third World.

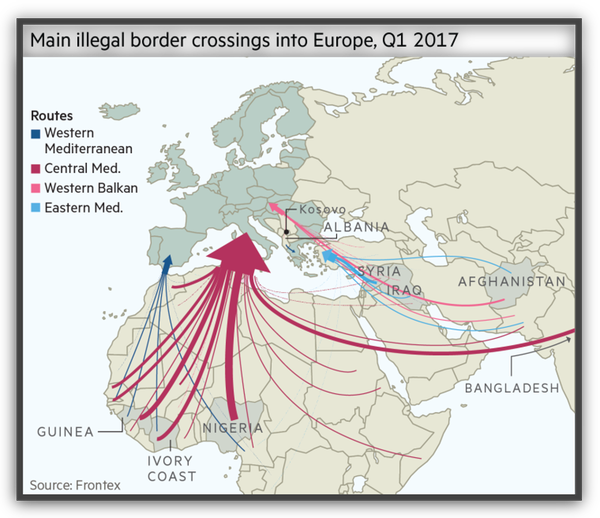

Unless there is rapid development there—both economic and social—the developed countries will be inundated by a human flood of Third World immigrants far beyond their economic, social, or cultural capacity to absorb.

But the forces that are creating post-capitalist society and post-capitalist polity originate in the developed world.

They are the product and result of its development.

Answers to the challenges of post-capitalist society and post-capitalist polity will not be found in the Third World.

…

The challenges, the opportunities, the problems of post-capitalist society and post-capitalist polity can only be dealt with where they originated.

And that is in the developed world.

Society, Polity, Knowledge

This book covers a wide range.

It deals with post-capitalist society; with post-capitalist polity; and with new challenges to knowledge itself.

Yet it leaves out much more than it attempts to cover.

It is not a history of the future.

Rather, it is a look at the present.

The areas of discussion—Society, Polity, Knowledge—are not arrayed in order of importance.

That would have put first the short discussion of the educated person which concludes this work.

The three areas are arrayed in order of predictability.

…

I am often asked whether I am an optimist or a pessimist.

For any survivor of this century to be an optimist would be fatuous.

We surely are nowhere near the end of the turbulences, the transformations, the sudden upsets, which have made this century one of the meanest, cruelest, bloodiest in human history.

…

Nothing “post” is permanent or even long-lived.

Ours is a transition period.

What the future society will look like, let alone whether it will indeed be the “knowledge society” some of us dare hope for, depends on how the developed countries RESPOND to the challenges of THIS transition period, the post-capitalist period—their intellectual leaders, their business leaders, their political leaders, but above all each of us in our own WORK and LIFE.

Yet surely this is a time to make the future—precisely because everything is in flux.

This is a time for action.

Making the future

From Capitalism to Knowledge Society

WITHIN ONE HUNDRED FIFTY YEARS, from 1750 to 1900, capitalism and technology conquered the globe and created a world civilization.

Neither capitalism nor technical innovations were new; both had been common, recurrent phenomena throughout the ages, in West and East alike.

What was brand new was their speed of diffusion and their global reach across cultures, classes, and geography.

And it was this speed and scope that converted capitalism into “Capitalism” and into a “system,” and technical advances into the “Industrial Revolution.”

This transformation was driven by a radical change in the meaning of knowledge.

In both West and East, knowledge had always been seen as applying to being.

Then, almost overnight, it came to be applied to doing.

It became a resource and a utility.

Knowledge had always been a private good.

Almost overnight it became a public good.

... snip, snip ...

Jumping over the remainder of the chapter introduction

and four major sections

here

The Management Revolution

When I decided in 1926 not to go to college but to go to work after finishing secondary school, my father was quite distressed; ours had long been a family of lawyers and doctors.

But he did not call me a “dropout.”

He did not try to change my mind.

And he did not prophesy that I would never amount to anything.

I was a responsible adult wanting to work as an adult.

Some thirty years later, when my son reached age eighteen, I practically forced him to go to college.

Like his father, he wanted to be an adult among adults.

Like his father, he felt that in twelve years of sitting on a school bench he had learned little, and that his chances of learning more by spending another four years on a school bench were not particularly great.

Like his father at that age, he was action-focused, not learning-focused.

And yet by 1958, thirty-two years after I had moved from high school graduate to trainee in an export firm, a college degree had become a necessity.

It had become the passport to careers.

Not to go to college in 1958 was “dropping out” for an American boy who had grown up in a well-to-do family and done well in school.

My father did not have the slightest difficulty in finding a trainee job for me in a reputable merchant house.

Thirty years later, such firms would not have accepted a high school graduate as a trainee; they would all have said, “Go to college for four years—and then you probably should go on to graduate school.”

In my father’s generation (he was born in 1876), going to college was for the sons of the wealthy and a very small number of poor but exceptionally brilliant youngsters (such as he had been).

Of all the American business successes of the nineteenth century, only one went to college: J. P. Morgan went to Göttingen to study mathematics, but dropped out after one year.

Few of the others even attended high school, let alone graduated from it.

By my time, going to college was already desirable; it gave one social status.

But it was by no means necessary nor much help in one’s life and career.

When I did the first study of a major business corporation, General Motors, the public relations department at the company tried very hard to conceal the fact that a good many of their top executives had gone to college.

The proper thing then was to start as a machinist and work one’s way up.

As late as 1950 or 1960, the quickest route to a middle-class income — in the United States, in Great Britain, in Germany (though no longer in Japan) — was not to go to college; it was to go to work at age sixteen in one of the unionized mass production industries.

There one could earn a middle-class income after a few months—the result of the productivity explosion.

Today these opportunities are practically gone.

Now there is practically no access to a middle-class income without a formal degree which certifies to the acquisition of knowledge that can only be obtained systematically and in a school.

The change in the meaning of knowledge that began two hundred fifty years ago has transformed society and economy.

Formal knowledge is seen as both the key personal and the key economic resource.

In fact, knowledge is the only meaningful resource today.

And knowledge in this new sense means knowledge as a utility, knowledge as the means to obtain social and economic results

Knowledge in action

These developments, whether desirable or not, are responses to an irreversible change: knowledge is now being applied to knowledge.

This is the third and perhaps the ultimate step in the transformation of knowledge.

Supplying knowledge to find out how existing knowledge can best be applied to produce results is, in effect, what we mean by management.

But knowledge is now also being applied systematically and purposefully to define what new knowledge is needed, whether it is feasible, and what has to be done to make knowledge effective.

It is being applied, in other words, to systematic innovation.

Purposeful innovation

This third change in the dynamics of knowledge can be called the “Management Revolution.”

Like its two predecessors — knowledge applied to tools, processes, and products, and knowledge applied to human work — the Management Revolution has swept the earth.

It took a hundred years, from the middle of the eighteenth century to the middle of the nineteenth century, for the Industrial Revolution to become dominant and worldwide.

It took some seventy years, from 1880 to the end of World War II, for the Productivity Revolution to become dominant and world-wide.

It has taken less than fifty years—from 1945 to 1990—for the Management Revolution to become dominant and worldwide.

All managers do the same things whatever the business of their organization.

Management as a liberal art

Management and the world’s work

thinking broad and thinking detailed

... snip, snip ...

That knowledge has become THE resource, rather than a resource, is what makes our society “post-capitalist.”

Moving Beyond Capitalism?

This fact changes—fundamentally—the structure of society.

It creates new social and economic dynamics.

The new worldview

Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Managing in the Next Society

“Embracing the future” followed by “the primacy of knowledge”

and then “the lego world”

It creates new politics.

Connections on this page:

The Society of Organizations The Society of Organizations

The Productivity of the New Work Forces The Productivity of the New Work Forces

From Command to Information From Command to Information

«§§§»

More on the management revolution

The memo THEY don't want you to see —

navigating a world moving toward unimagined futureS

Management Worldviews

From Knowledge To Knowledges

Most MISTAKES IN THINKING

are mistakes in PERCEPTION:

SEEING only part of the situation #sda ;

JUMPING to conclusions;

MISINTERPRETATION caused by feelings

… finding and selecting

the pieces of the puzzle

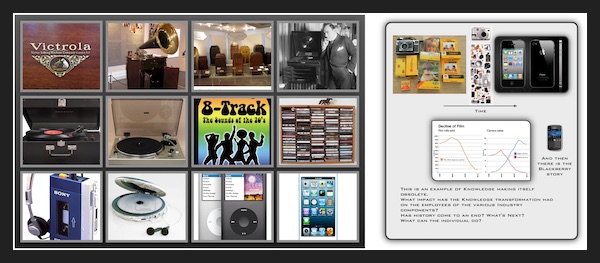

Underlying all three phases in the shift to knowledge — the Industrial Revolution, the Productivity Revolution, and the Management Revolution—is a fundamental change in the meaning of knowledge.

We have moved from

knowledge in the singular

to knowledgeS in the plural.

Traditional knowledge was general.

sidebar ↓

The Educational Revolution (circa 1957)

A sudden, sharp change

has occurred

in the

meaning

and impact of

knowledge for society

«§§§»

Knowledge and technology today

… is a symptom of the shift in the meaning of knowledge

from an end in itself

to a resource,

that is, a means to some result.

Knowledge as the

central energy

of a modern society

exists altogether

in application

and when it is put to work.

Work, however, cannot be defined in terms of the disciplines.

End results are interdisciplinary of necessity. continue

Drucker — My life as a knowledge worker

main brainroad continues ↓

What we now consider knowledge is of necessity highly specialized.

We never before spoke of a “man (or woman) of knowledge”; we spoke of an “educated person.”

Educated people were generalists.

Try a page search for “educated person”

They knew enough to talk or write about a good many things, enough to understand a good many things.

But they did not know enough to do any one thing.

As an old saying has it: You would want an educated person as a guest at your dinner table, but you would not want him or her alone with you on a desert island, where you need somebody who knows how to do things.

… situations that require EFFECTIVE action

But in today’s university the traditional “educated people” are not considered “educated” at all.

They are looked down on as dilettantes.

The Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur’s Court, the hero of the 1889 book by Mark Twain, was not an educated person.

He surely knew neither Latin nor Greek, had probably never read Shakespeare, and did not even know the Bible well.

But he knew how to do everything mechanical, up to and including generating electricity and building telephones.

The purpose of knowledge for Socrates, as said earlier, was self-knowledge and self-development; results were internal.

For his antagonist, Protagoras, the result was the ability to know what to say and to say it well.

It was “image,” to use a contemporary term.

For more than two thousand years, Protagoras’s concept of knowledge dominated Western learning and defined knowledge.

The medieval trivium, the educational system that up to this day underlies what we call a “liberal education,” consisted of grammar, logic, and rhetoric—the tools needed to decide what to say and how to say it.

They are not tools for deciding what to do and (deciding) how to do it.

sidebar ↓

“Education teaches reading, writing, arithmetic and a lot of knowledge (information).

The reading, writing and arithmetic are basic skills which everyone needs to survive in society — and to contribute.

There is, however, a skill missing from traditional education.

This is the skill of thinking.

I do not mean thinking in the sense of argument or #analysis but thinking in the sense of '#effectiveness'. explore

This is the thinking needed to get things done : objectives, priorities, alternatives, other people's views, idea creativity, decisions, choices, planning, #consequences of action.

We have literacy and numeracy but we need 'operacy' or the skill of doing.

Many years ago I designed the CoRT thinking lessons for the deliberate and direct teaching of thinking as a school subject.

These lessons are now widely used throughout the world with several countries making them compulsory in all schools.

There is increasing use of the lessons in the USA, Canada and Australia and a more limited use in China and Malaysia.

Intelligence is a potential just like the horsepower of a car.

To use that potential the driver needs to develop skill.

That is the skill of thinking.

Education must teach effectiveness.

#Knowledge (#information) is not enough.

Knowledge without effectiveness can be very dangerous.

It can mean that the people with knowledge get into positions of power and do not know how to be effective.

The new education of the positive revolution must teach the thinking skills necessary for #effectiveness, leadership and the skills of dealing with other people.” — Handbook for the Positive Revolution

«§§§»

Unless you can teach the right answer to every conceivable situation, then the skill of thinking is needed continue

main brainroad continues ↓

“The Zen concept of knowledge and the Confucian concept of knowledge—the two concepts that dominated Eastern learning and Eastern culture for thousands of years—were similar.

The first focused on self-knowledge; the second—like the medieval trivium—on the Chinese equivalents of grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

The knowledge we now consider knowledge proves itself in action. continue

What we now mean by knowledge is information EFFECTIVE in action, information focused on results.

These results are seen outside the person—in society and economy, or in the advancement of knowledge itself.

To accomplish anything, this knowledge has to be highly specialized.

This was the reason why the tradition—beginning with the ancients but still persisting in what we call “liberal education”—relegated it to the status of a technē, or craft.

It could neither be learned nor taught; nor did it imply any general principle whatever.

It was specific and specialized — experience rather than learning, training rather than schooling.

But today we do not speak of these specialized knowledges as “crafts”; we speak of “disciplines.”

This is as great a change in intellectual history as any ever recorded.

A discipline converts a “craft” into a methodology—such as engineering, the scientific method, the quantitative method, or the physician’s differential diagnosis.

Each of these methodologies converts ad hoc experience into system.

Each converts anecdote into information.

Each converts skill into something that can be taught and learned.

«§§§»

The shift from knowledge to knowledges has given knowledge the power to create a new society.

But this society has to be structured on the basis of knowledge as something specialized, and of knowledge people as specialists.

Knowledge people within an organization

sidebar ↓

To know something,

to really understand

something important,

one must look at it

from sixteen different angles ↓

Drucker: political/social ecologist

How Much Labor Is Needed—and What Kind?

The Productivity of the New Work Forces

Most MISTAKES IN THINKING

are mistakes in PERCEPTION:

SEEING only part of the situation #sda;

JUMPING to conclusions;

MISINTERPRETATION caused by feelings

The Danger of Too Much Planning

The Three Stonecutters

The Individual in Entrepreneurial Society

Reinvent Yourself

Knowledge: Its Economics and Its Productivity

The leading social groups of the knowledge society

knowledge industries, work, worker

main brainroad continues ↓

This is what gives them their power.

But it also raises basic questions—of values, of vision, of beliefs, of all the things that hold society together and give meaning to our lives.

DETOUR → As the last chapter of this book will discuss, it also raises a big—and a new-question: what constitutes the educated person in the society of knowledgeS?

«§§§»

“For almost nothing

in our educational systems

prepares people

for the #reality

in which they will live, work,

and become #effective” —

Google search

Druckerism and intellectual capitalist #lms #education

How could an education system prepare us

for unknown and unpredictable future #realitieS?

«§§§»

The Educational Revolution circa 1957

A sudden, sharp change has occurred

in the meaning and impact of

knowledge for society

The New Pluralism ::: The Society of Organizations

Knowledge Economy and Knowledge Polity

Management and the World’s Work

Knowledge and technology

Knowledge and human development

that man must die …

The knowledge

we now consider

knowledge …

connect only connect …

… “Power has to be used.

It is a reality.

If the decent and idealistic toss power in the gutter, the guttersnipes pick it up — the antidote.

If the able and educated refuse to exercise power responsibly, irresponsible and incompetent people take over the seats of the mighty and the levers of power.

Power not being used for social purposes passes to people who use it for their own ends.

At best it is taken over by the careerists who are led by their own timidity into becoming arbitrary, autocratic, and bureaucratic.”

PFD

PDF outline of selected topics

Notes on the transformation

Information is not enough — thinking is needed.

Dense reading and Dense listening

Thinking broad and Thinking detailed.

What’s the broad idea? and what can be done to carry it out?

The Society of Organizations concept outline

A PDF version → society of organizations brainroad

The need for a theory of organizations …

… toward a theory of organizations

-

An organization is …

-

a special-purpose institution.

-

A human group composed of specialists — not labors

-

Working together on a common task

-

The function of organizations

-

To make knowledge productive

-

The more specialized knowledges are, the more effective they will be

-

Have to be put together with the work of other specialist to become results (on the outside)

-

Specialist are effective only as specialists—and knowledge workers have to be effective

-

Specialist need exposure to the universe of knowledge

-

And for this to produce results, an organization is needed

-

Organization as a distinct species

-

All one species …

-

Armies

-

Churches

-

Universities

-

Hospitals

-

Businesses

-

Labor unions

-

They are the man-made environment, the “social ecology” of post-capitalist society

-

Management is a generic function pertaining to all organizations

-

The characteristics of organizations

-

Organizations are special-purpose institutions

-

Its mission must be crystal clear

-

Because the organization is composed of specialists

-

Otherwise its members become confused

-

They will follow their specialty

-

Rather than applying it to the common task

-

They will each define “results” in terms of that specialty

-

Only a clear, focused, and common mission can hold the organization together and enable it to produce results

-

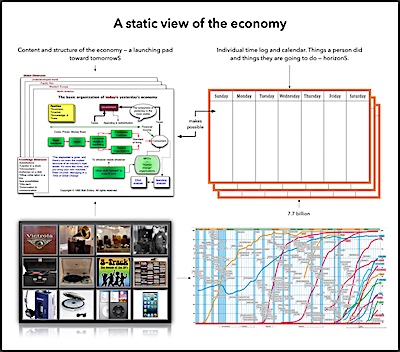

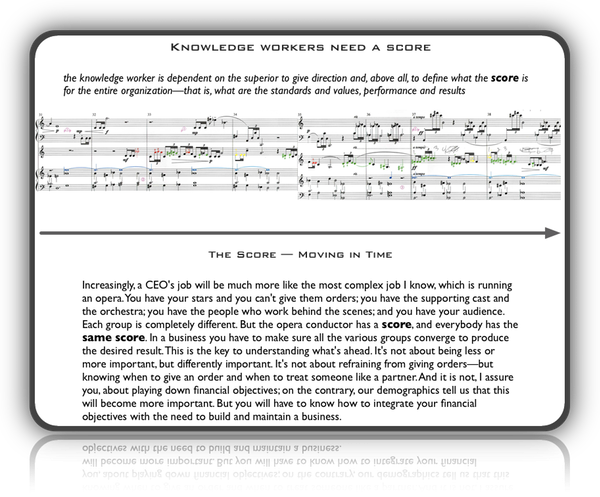

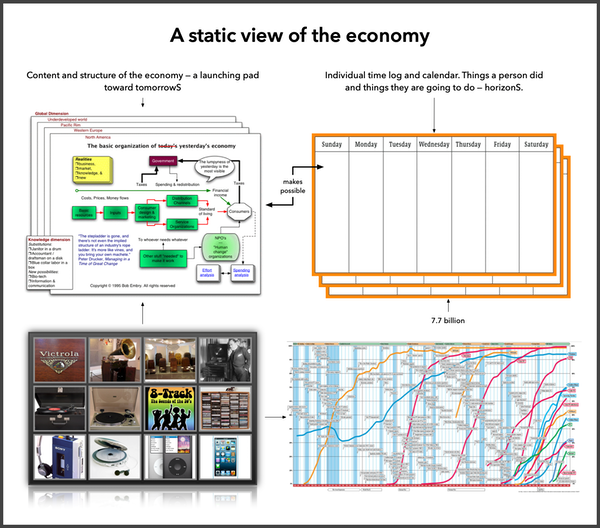

The prototype of the modern organization is the symphony orchestra

-

Many high-grade specialists

-

By themselves they don’t make music. Only the orchestra can do that

-

Perform because they have the same score

-

Results exist only on the outside

-

Organizations exist to produce results on the outside

-

Discussion of “profit centers” vs. “cost-centers”

-

Results in an organization are always pretty far away from what each member contributes

-

Results need to be defined clearly and unambiguously

-

Organizations need to appraise and judge itself and its performance against clear, known, impersonal objectives and goals

-

“Voluntary” membership and the ability to leave an organizations

-

Organizations are always in competition for its essential resource qualified, knowledgeable, dedicated people

-

Need to market membership (what do the jobs really have to be to attract the needed people)

-

Have to attract people

-

Have to hold people

-

Have to recognize and reward people

-

Have to motivate people

-

Have to serve and satisfy people

-

Has to be an organization of equals, of “colleagues,” of “associates”

-

They are always managed

-

Have “leaders”

-

May be perfunctory and intermittent

-

Or may be a full-time and demanding job for a fairly large group of people

-

Have to be people who make decisions

-

Have to be people who are accountable for the organization’s

-

mission

-

spirit

-

performance

-

results

-

Must be a “conductor” who controls the “score”

-

There have to be people who

-

focus the organization on its mission

-

set the strategy to carry it out

-

define what the results are

-

This management has to have considerable authority

-

To be able to perform, an organization must be autonomous

-

Organization as a destabilizer

-

The organization of the post-capitalist society of organizations is a destabilizer

-

Its function is to put knowledge to work

-

It must be organized for constant change

-

It must be organized for innovation

-

It must be organized for systematic abandonment of …

-

the established

-

the customary

-

the familiar

-

the comfortable

-

products, services, and processes

-

human and social relationships

-

skills

-

organizations themselves

-

Knowledge changes fast

-

Every organization has to build into its very structure the management of change

-

Post-capitalist society has to be decentralized

-

Organizations in the post-capitalist society thus constantly upset, disorganize, and destabilize the community

-

The “culture” of the organization must transcend community

-

It is the nature of the task that determines the culture of an organization, rather than the community in which that task is being performed

-

If the organization’s culture clashes

-

with the values of the community

-

the organization’s culture will prevail

-

or else the organization will not make its social contribution

-

”Knowledge knows no boundaries”

-

Of necessity every knowledge organization is of necessity non-national, non-community

-

Even if totally embedded in the local community

-

The employee society

-

Another way to describe the phenomenon of the society of organizations

-

Employees who work in subordinate and menial occupations

-

Knowledge workers

-

1/3 of the work force

-

They own the “means of production”

-

Cannot, in effect, be supervised

-

Cannot be told what to do, how to do it, how fast to do it and so on

-

Unless they know more than anybody else in the organization they are to all intents and purposes useless

-

They hold a crucial card in their mobility

-

Organizations and knowledge workers are interdependent

-

”Loyalty” will have to be earned by proving to knowledge employees that the organization which presently employs them can offer them exceptional opportunities to be effective

-

Capital now serves the employee

From command and control to information-based to responsibility-based organizations

↑ thinking broad and thinking detailed ↓

The Characteristics of Organizations

Organizations are special-purpose institutions.

They are effective because they concentrate on one task.

If you were to go to the American Lung Association and say: “Ninety percent of all adult Americans [it’s always 90 percent, by the way] suffer from ingrown toenails; we need your expertise in research, health education, and prevention to stamp out this dreadful scourge,” you’d get the answer: “We are interested only in what lies between the hips and the shoulders.”

That explains why the American Lung Association or the American Heart Association or any of the other organizations in the health field get results.

Society, community, family have to deal with whatever problem arises.

To do so in an organization is “diversification.”

And in an organization, diversification means splintering.

It destroys the performance capacity of any organization—whether business, labor union, school; hospital, community service, or church.

Drucker and Me

Organization is a tool.

As with any tool, the more specialized its given task, the greater its performance capacity.

Because the organization is composed of specialists, each with his or her own narrow knowledge area, its mission must be crystal clear.

The organization must be single-minded, otherwise its members become confused.

They will follow their specialty rather than applying it to the common task.

They will each define “results” in terms of that specialty, imposing their own values on the organization.

Only a clear, focused, and common mission can hold the organization together and enable it to produce results.

Without such a focused mission, the organization soon loses credibility.

A good example is what happened to American Protestantism in the post-World War II period.

Very few strategies have ever been as successful as that, of the American Protestant churches when around 1900 they focused their tremendous resources on the social needs of a rapidly industrializing urban society.

The doctrine of “Social Christianity” was a major reason why the churches in America did not become marginal, as the churches in Europe did.

Yet social action is not the mission of a Christian Church.

That is to save souls.

Because Social Christianity was so successful, the churches, especially since World War II, have dedicated themselves more and more wholeheartedly to social causes.

Ultimately, liberal Protestantism used the trappings of Christianity to further social reform and to promote actual social legislation.

Churches became social agencies.

They became politicized—and as a result they rapidly lost cohesion, appeal, and members.

The prototype of the modern organization is the symphony orchestra.

Each of the two hundred fifty musicians in the orchestra is a specialist, and a high-grade one.

Yet by itself the tuba doesn’t make music; only the orchestra can do that.

The orchestra performs only because all two hundred fifty musicians have the same score.

They all subordinate their specialty to a common task.

And they all play only one piece of music at any given time.

Results in an organization exist only on the outside.

Society, community, family are self-contained and self-sufficient; they exist for their own sake.

But all organizations exist to produce results on the outside.

Inside a business, there are only costs.

The term “profit center” (which, alas, I myself coined many years ago) is a misnomer.

Inside a business, there are only cost centers.

There are profits only when a customer has bought the product or the service and, has paid for it.

The result of the hospital is a cured patient, who can go back home (and who fervently hopes never to have to return to the hospital).

The results of the school or the university are graduates who put to work what they have learned in their own lives and work.

The results of an army are not maneuvers and promotions for generals; they are deterring a war or winning it.

The results of the Church are not even on this earth.

This means that results in an organization are always pretty far away from what each member contributes.

This is true even in the hospital, where individual contributions—those of the nurse or the physical therapist—are closely related to the result: a cured patient.

But many specialists even in the hospital cannot identify their contribution to any particular result.

What share in the recovery or rehabilitation of a patient does the X-ray technician have?

Or the clinical laboratory technician?

Or the dietitian?

In most institutions, the individual’s contribution is totally swallowed up by the task and disappears in it.

What use is the best engineering department if the company goes bankrupt?

And yet, unless the engineering department is first-class, dedicated, and hardworking, the company is likely to go bankrupt.

Each member in an organization, in other words, makes a vital contribution (at least in theory) without which there can be no results.

But none by himself or herself produces these results.

This then requires, as an absolute prerequisite of an organization’s performance, that its task and mission be crystal clear.

Results need to be defined clearly and unambiguously—and, if at all possible, measurably.

This also requires that an organization appraise and judge itself and its performance against clear, known, impersonal objectives and goals.

Neither society nor community nor family need to set such goals, nor could they.

Survival rather than performance is their test.

Joining an organization is always a decision.

De facto there may be little choice.

But even where membership is all but compulsory—as membership in the Christian Church was in Europe for many centuries for all but a handful of Jews and Gypsies—the fiction of a decision to join is carefully maintained.

The godfather at the infant’s baptism pledges the child’s voluntary acceptance of membership in the Church.

It may be difficult to leave an organization—the Mafia, for instance, or a Japanese big company, or the Jesuit Order.

But it is always possible.

And the more an organization becomes an organization of knowledge workers, the easier it is to leave it and move elsewhere (see “The Employee Society” later in this chapter).

Unlike society, community, and family, an organization is therefore always in competition for its most essential resource: qualified, knowledgeable, dedicated people.

This means that organizations have to market membership, fully as much as they market their products and services—and perhaps more.

They have to attract people, have to hold people, have to recognize and reward people, have to motivate people, have to serve and satisfy people.

Because modern organization is an organization of knowledge specialists, it has to be an organization of equals, of “colleagues,” of “associates.”

No one knowledge “ranks” higher than another.

The position of each is determined by its contribution to the common task rather than by any inherent superiority or inferiority.

“Philosophy is the queen of the sciences,” says an old tag.

But to remove a kidney stone, you want a urologist rather than a logician.

The modern organization cannot be an organization of “boss” and “subordinate”; it must be organized as a team of “associates.”

An organization is always managed.

Society, community, family may have “leaders”—and so do organizations.

But organizations, and organizations alone, are managed.

The managing may be perfunctory and intermittent—as it is, for instance, in the Parent-Teachers Association at a suburban school in the United States, where the elected officers spend only a few hours each year on the organization’s affairs.

Or management may be a full-time and demanding job for a fairly large group of people, as in the military, the business enterprise, the labor union, the university, and so on.

But there have to be people who make decisions, or nothing will ever get done.

There have to be people who are accountable for the organization’s mission, its spirit, its performance, its results.

There must be a “conductor” who controls the “score.”

Larger view of the image above ::: Leader of tomorrow

There have to be people who focus the organization on its mission, set the strategy to carry it out, and define what the results are.

This management has to have considerable authority.

Yet its job in the knowledge organization is not to command; it is to direct.

Finally, to be able to perform, an organization must be autonomous.

Legally, it may be a government agency, as are Europe’s railways, America’s state universities, or Japan’s leading radio and television network, NHK.

Yet in actual operation these organizations must be able to “do their own thing.”

If they are used to carry out “government policy,” they immediately stop performing.

All this, it will be said, is obvious.

Yet every one of these characteristics is new, and indeed unique to that new social phenomenon, the organization.

Taking relationship responsibility

From command to responsibility-based organization and

Managing the boss — boss list

The Society of Organizations PDF

Is Labor Still an Asset?

American manufacturing production remained almost unchanged as a percentage of gross national product in the years of the “manufacturing decline.”

Peter Drucker Sets Us Straight

It stood at 22 percent of GNP in 1975, and at 23 percent in 1990.

During those twenty years, gross national product increased two and a half times.

In other words, total American manufacturing production grew more than two and a half times in those twenty years.

But manufacturing employment did not increase at all.

On the contrary, manufacturing employment went down from 1960 to 1990 as a percentage of the work force and even in absolute numbers.

It fell by almost half in these thirty years, from 25 percent of the total labor force in 1960 to 16 or 17 percent in 1990.

During this time, the total American work force doubled the largest increase ever recorded by any country in peacetime.

All the increase was, however, in jobs other than making and moving things.

These trends are certain to continue.

Unless there is a severe depression, manufacturing production in America is likely to stay at about the same 23 percent of gross national product, which, for the next ten or fifteen years, should mean another near doubling.

During the same period, however, employment in manufacturing is likely to fall to 12 percent or less of the total labor force.

That would mean a further fairly sharp shrinkage of the total number of people employed in manufacturing work.

The development in Japan is almost identical.

There, too, total manufacturing production has increased two and a half times in the twenty years between 1970 and 1990.

There, too, however, manufacturing employment in total numbers has not increased at all.

And there too, from now on, even a sizable increase in manufacturing production will not be sufficient to offset the steady shrinkage in manufacturing jobs.

In Japan, too, by the year 2000 total employment in manufacturing will be substantially less than it was in 1990.

The response of these two countries to identical developments is, however, completely different.

In the United States, there is gloom about the “decline of American manufacturing,” if not panic about the “death of American manufacturing.”

In the United States, manufacturing is equated with blue-collar employment.

In Japan, the reaction has been the opposite.

What matters to the Japanese is the increase in manufacturing production.

Japan sees the trends of the last twenty years as victory; America sees them as defeat.

Japan sees the glass as “half full”; America as “half empty.”

As a result of these differences in attitude, the policies of the two countries also differ radically.

Every state, county, and city in America is desperately trying to attract manufacturers who offer blue-collar jobs.

Poor rural states like Kentucky and Tennessee have lured Japanese automobile manufacturers with offers of long-range tax benefits and low-interest loans.

The city of Los Angeles in early 1992 awarded a multi-billion-dollar contract for rapid-transit equipment to the company that promised to create all of ninety-seven manufacturing jobs in a region that has almost 15 million inhabitants!

By contrast, Japanese companies are moving manual work in manufacturing out of Japan as fast as they can into the United States; into plants at the U.S.-Mexican border; into Indonesia.

In the United States, manufacturing jobs are seen as a priceless asset.

In Japan, they are more and more seen as a liability.

Differences in social structure between the two countries explain, in part, these different reactions to the same trends.

The shrinkage of manual jobs in making and moving things is above all a threat to America’s most visible minority, the blacks.

Their biggest economic gains during the last thirty years have come from moving into well-paid jobs in unionized mass production industries.

In all other areas of economy and society black gains have been much more modest.

The shrinkage of jobs in the unionized mass production industries therefore aggravates what all along has been America’s most serious problem—all the more daunting since it is as much a problem of conscience as it is a social problem.

In Japan, practically all young people now get a high school degree, and then are considered overqualified for manual work.

They become clerical workers.

Those who go on to the university—and the same proportion of young males goes to the university in Japan as in the United States—take managerial or professional jobs only.

If Japan were not able to cut down on the number of manual jobs in manufacturing, it would face an extreme labor shortage.

In other words, the shrinkage in manufacturing jobs is the answer to a problem for the Japanese.

A country needs a manufacturing base, so Americans would argue—and most Europeans as well.

This means manufacturing jobs.

But the Japanese argue—convincingly—that the supply of young people in the developing countries qualified for nothing but manual work in manufacturing is so large—and will remain so large for at least another thirty years—that worrying about the “industrial base” is nonsense.

A country that has the knowledge workers to design products and to market them will have no difficulty getting those products made at low cost and high quality.

In fact, the Japanese argue that to encourage blue-collar manual work in making and moving things weakens a developed economy.

In a developed economy, even people who learn little in school represent a tremendous educational investment.

Employed as manufacturing workers, such people yield only a pitiful return to society and economy, perhaps no more than 1 or 2 percent.

Yet people in developing countries who have had no schooling are fully as productive after a little training as any manual worker in the most highly developed country.

Economically as well as socially; it would be much more productive—the Japanese argue—to put the money spent to create blue-collar jobs in developed countries instead into advancing the country’s education, and thus to ensure that youngsters learn enough to become qualified, for knowledge work, or at least for high-level service work.

How Much Labor Is Needed—and What Kind?

A developed country does indeed need a manufacturing base.

Production

Peter Drucker Sets Us Straight

Yet the facts support the Japanese position.

The United States still has the world’s strongest agricultural base, even though farmers now constitute only 3 percent of the working population (they still formed 25 percent at the end of World War II).

The United States equally could still be the world’s largest manufacturer, with manufacturing workers constituting no more than 10 percent (or less) of the working population.

In 1980, United States Steel, America’s largest integrated steel company, employed 120,000 people in steel production.

Ten years later, it employed 20,000 people in steel production, and yet produced almost the same steel tonnage.

Within ten years the productivity of the manual worker engaged in steelmaking had increased seven-fold.

A large part of the increase was obtained by closing down old, outmoded plants.

Another large part of the increase came from investment in new equipment.

But the lion’s share of the jump in productivity represents the results of reengineering work flow and tasks.

As a result, U.S. Steel’s best mills are now the world’s most productive integrated steelmakers.

And yet, like all integrated steel mills the world over, they are still grossly overstaffed.

And America’s integrated steel mills are still losing money.

The so-called minimills (in 1991, almost one third of all steel produced in the U.S. was produced by minimills) are again three to four times as productive as the most productive integrated mill.

The best of American minimills could probably produce as much steel as U.S. Steel does with not much more than one sixth of U.S. Steel’s present employment.

And increasingly the minimills can turn out all the products an integrated steel mill produces and of the same quality.

Admittedly, a minimill obtains these results by not having to perform the most labor-intensive operations in an integrated steel mill.

It does not smelt iron ore to obtain iron; nor does it convert iron into steel.

It starts with scrap steel.

But for the foreseeable future, the world will have abundant supplies of scrap steel.

It is not the process that is the main difference between the integrated steel mill and the minimill.

Workers in the minimill are not blue-collar workers making and moving things; they are knowledge workers.

The minimill changes steelmaking from applying muscle and skill to work to applying knowledge to work: knowledge of the process; of chemistry; of metallurgy; of computer operations.

The workers whom U.S. Steel laid off need not apply at the minimill.

This is an extreme example, to be sure.

But it indicates the general direction.

Plenty of people will always be needed who can bring only muscle to the job.

With our present knowledge of training, they can quickly be made productive in traditional jobs.

Even more people will be needed who can only bring manual skills to the job.

But the greatest employment need of the next decades will be for “technicians.”

Technicians not only need a high level of skill; they also need a high degree of formal knowledge, and above all a high capacity to learn and to acquire additional knowledge.

Technicians are not the successors to yesterday’s blue-collar, workers.

They are basically the successors to yesterday’s highly skilled workers; or rather,— they are highly skilled workers who now also possess a substantial amount of formal knowledge, formal education, and the capacity for continuous learning.

A hot dispute is raging today in Academia and among policy makers: Is it a sufficient “manufacturing base” for developed countries to have their businesses carry on at home the work on technology, design, and marketing of industrial products, or do they also have to manufacture at home?

The question is moot.

If a country has the knowledge base, it will also manufacture.

But this manufacturing work will not be competitive if carried out by traditional blue-collar workers who serve the machine.

In competitive manufacturing, the work will largely be done by knowledge workers whom the machine serves—as computer consoles and computerized work stations serve the ninety-seven technicians in a steelmaking minimill.

This will create tremendous problems for developing countries.

They can no longer expect to be able to obtain large numbers of manufacturing jobs by training low-wage people.

Manual labor, no matter how cheap, will not be able to compete with knowledge labor, no matter how well paid.

But this also creates tremendous problems for countries—the United States is the prime example—in which there are large groups of “minority” people who are “developing” rather than “developed” in their educational qualifications.

The United Kingdom in its old working-class enclaves in the north, in Scotland (especially along the Clyde), and in Northern Ireland faces a similar problem of a working-class culture which in effect is the culture of a developing rather than a developed country.

On the continent of Europe, too, despite an educational system with relatively open access, the trend toward labor becoming a liability rather than an asset will, for a fairly long transition period, create both serious social problems and political conflicts.

Everywhere this trend also raises difficult and highly emotional questions about the role, function, and future of this century’s most successful organization, the labor union.

To maintain and strengthen a country’s manufacturing base and to ensure that it remains competitive surely deserves high priority.

But this means accepting that manual labor in making and moving things is rapidly becoming a liability rather than an asset.

Knowledge has become the key resource for all work.

Creating traditional manufacturing jobs—as the Americans, the British, and the Europeans are still doing—is at best a short-lived expedient.

It may actually make things worse.

The only long-term policy which promises success is for developed countries to convert manufacturing from being labor based into being knowledge based.

The Productivity of the New Work Forces

You can only work with the things on your mental radar

The new challenge facing the post-capitalist society is the productivity of knowledge workers and service workers.

To improve the productivity of knowledge workers will in fact require drastic changes in the structure of the organizations of post-capitalist society, and in the structure of society itself.

Forty years ago, people doing knowledge work and service work formed still less than one third of the work force.

Today, such people account for three quarters if not four fifths of the work force in all developed countries—and their share is still going up.

Their productivity, rather than the productivity of the people who make and move things, is THE productivity of a developed economy.

It is abysmally low.

The productivity of people doing knowledge work and service work may actually be going down rather than going up.

One third of the capital investment in developed countries in the last thirty years has gone into equipment to handle data and information, computers, fax machines, electronic mail, closed-circuit television, and so on.

Yet the number of people doing clerical work, that is, the number of people to whose work most of this equipment is dedicated, has been going up much faster than total output or gross national product.

Instead of becoming more productive, clerical workers have become less productive.

The same is true of salespeople and also of engineers.

The Daily Drucker

And no one, I dare say, would maintain that the teacher of 1990 is more productive than the teacher of 1900 or the teacher of 1930.

The lowest level of productivity occurs in government employment.

And yet governments everyplace are the largest employers of service workers.

In the United States, for instance, one fifth of the entire work force is employed by federal, state, and local governments, predominantly in routine clerical work.

How to guarantee non-performance

Conditions for survival

In the United Kingdom, the proportion is roughly one third.

In all developed countries, government employees account for a similar share of the total work force.

Unless we can learn how to increase the productivity of knowledge workers and service workers, and increase it fast, the developed countries will face economic stagnation and severe social tension.

People can only get paid in accordance with their productivity.

Their productivity creates the pool of wealth from which wages and salaries are then paid.

If productivity does not go up, let alone if it declines, higher real incomes cannot be paid.

Knowledge workers are likely to be able to command good incomes, regardless of their productivity or the productivity of the total economy.

They are in a minority; and they have mobility.

But even knowledge workers, in the long run, must suffer a decline in real income unless their productivity goes up.

Large numbers of service workers perform work that demands fairly low skills and relatively little education.

If an economy in which service worker productivity is low tries to pay them wages considerably above what their productivity produces, inflation must erode everybody’s real income.

In the not so long run, inflation will then also create serious social tensions.

If service workers, however, are paid only according to their productivity, the gap between their income and that of the “privileged,” that is, the knowledge workers, must steadily widen-again creating severe social tensions.

Knowledge: its economics and productivity

A good deal of service work does not differ too much from the work of making and doing (moving?) things.

This includes such clerical jobs as data processing, billing, answering customers’ inquiries, handling insurance claims, issuing drivers’ licenses to motorists—in fact, about two thirds of all the work done in government offices, and about one third or more of all the clerical and services work done in businesses, in universities, in hospitals, and so on.

This is in effect “production work,” which differs from the work done in the factory only in that it is being done in an office.

But even this work has first to be “re-engineered” before it can be made productive.

It has to be studied and restructured for optimum contribution and achievement.

In all other work done by the new work forces, both knowledge workers and service workers, raising productivity requires new concepts and new approaches.

In the work on productivity in making and moving things, the task is given and determined.

When Frederick W. Taylor started to study the shoveling of sand, he could take it for granted that the sand had to be shoveled.

In a good deal of the work of making and moving things, the task is actually “machine-paced”: the individual worker serves the machine.

In knowledge work, and in practically all service work, the machine serves the worker.

The task is not given; it has to be determined.

The question, “What are the expected results from this work?” is almost never raised in traditional work study and Scientific Management.

But it is the key question in making knowledge workers and service workers productive.

And it is a question that demands risky decisions.

There is usually no right answer; there are choices instead.

And results have to be clearly specified, if productivity is to be achieved.

The new productivity challenge

Chapter 19 in Management, Revised Edition

Chapter 5 in Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Knowledge: Its Economics and Productivity

… This means a radical change in structure for the organizations of tomorrow.

It means that the big business, the government agency, the large hospital, the large university will not necessarily be the one that employs a great many people.

Outsourcing (not offshoring) ::: Making the future

It will be the one that has substantial revenues and substantial results—achieved in large part because it itself does only work that is focused on its mission; work that is directly related to its results; work that it recognizes, values, and rewards appropriately.

The rest it contracts out.

What Kind of Team?

There is a second major difference between the productivity of making and moving things and the productivity of knowledge work and service work.

In knowledge and service work, we have to decide how the work should be organized.

What kind of human team is appropriate for this kind of work and its flow?

Most human work is carried out in teams; hermits are exceedingly rare.

Even the most solitary artists, writers, or painters, depend on others for their work to become effective—the writer on an editor, a printer, a bookstore; the painter on a gallery to sell his or her work; and so on.

And most of us work in far closer relationship to our teammates.

There is a great deal of talk today about “creating teamwork.”

This is largely a misunderstanding.

It assumes that the existing organization is not a team organization, and that is demonstrably false.

It secondly assumes that there is only one kind of team; but in effect there are three major kinds of teams for all human work.

And for work to be productive, it has to be organized into the team that is appropriate to the work itself, and its flow.*1

The first kind of team is exemplified by the baseball or cricket team; it is also the kind of team that operates on a patient in the hospital.

In this team, all players play on the team but they do not play as a team.

Each player on a baseball or a cricket team has a fixed position which he never leaves.

In baseball, the outfielders never assist each other.

They will stay in their respective positions.

“If you are up at bat, you are totally alone,” is an old baseball saying.

Similarly, the anesthesiologist will not come to the assistance of the surgical nurse or the surgeon.

This team does not enjoy a good press today.

In fact, when people talk about “building teams,” they usually mean that they want to move away from this kind of team.

Yet the baseball-or cricket-team has great strengths that should not be discounted.

Because all players occupy fixed positions, they can be given specific tasks of their own, can be measured by performance scores for each task, can be trained for each task.

It is by no means accidental that in both baseball and cricket there are statistics on every player, going back for decades.

The surgical team in the hospital functions much the same way.

For repetitive tasks and for work in which the rules are well known, the baseball team is the ideal.

And it was this model on which modern mass production—the work of making and moving things—was organized, and to which it owes a great deal of its performance capacity

The second type of team is the soccer team.

It is also the team concept on which the symphony orchestra is organized, and the model for the hospital team that rallies around the patient who goes into cardiac arrest at two in the morning.

On this team, too, all players have fixed positions.

The tuba players in the orchestra will not take over the parts of the double basses.

They stick to their tubas.

In the crisis team at the hospital, the respiratory technician will not make an incision in the chest of the patient to massage the heart.

But on these teams, the members work as a team.

Each coordinates his or her part with the rest of the team.

This team requires a conductor or a coach.

And the word of the conductor or coach is law.

It also requires a “score.”

And it requires endless rehearsals to work well.

But, unlike the baseball team, it has great flexibility if the score is clear and if the team is well led.

And it can move very fast.

Finally, there is the doubles tennis team—the team also of the jazz combo or of the four or five senior executives who together constitute the “President’s Office” — in the large American company, or the Vorstand (board of management) in the German company.☨2

This team has to be small—seven to nine people may be the maximum.

The players have a “preferred” rather than a “fixed” position; they “cover” for one another.

And they adjust themselves to the strengths and weaknesses of each other.

The player in the back court in doubles tennis adjusts to the strengths and weaknesses of the partner who plays the net.

And the team only functions when this adjustment to the strengths and weaknesses of the partners has become conditioned reflex, that is, when the player in the back court starts running to “cover” for the weak backhand of the partner at the net the moment the ball leaves the racket of the player on the other side.

A well-calibrated team of this kind is the strongest team of all.

Its total performance is greater than the sum of the individual performances of its members, for this team uses the strength of each member while minimizing the weaknesses of each.

But this team requires enormous self-discipline.

The members have to work together for a long time before they actually function as a “team.”

These three types of teams cannot be mixed.

One cannot play baseball and soccer with the same team on the same field at the same time.

The symphony orchestra cannot play the way a jazz combo plays.

The three teams must also be “pure”; they cannot be hybrids.

And to change from one team to another is exceedingly difficult and painful.

The change cuts across old, long-established, and cherished human relationships.

Yet any major change in the nature of the work, its tools, its flow, and its end product may require changing the team.

This is particularly true with respect to any change in the flow of information.

In the baseball-type team, players get their information from the situation.

Each receives information appropriate to his or her task, and receives it independently of the information the teammates all receive.

In the symphony orchestra or the soccer team, the information comes largely from conductor or coach.

They control the “score.”

In the doubles tennis team, the players get their information largely from each other.

This explains why the change in information technology, and the move to what I have called the “information-based organization” has made necessary massive “re-engineering.”♰3

The new information technology underlies the strenuous efforts of American corporations in the last ten years to “reengineer” themselves.

Traditionally, most work in large American companies was organized on the baseball team model.

Top management consisted of a chief executive officer to whom senior functional executives “reported,” each doing a specific kind of work—running the factories, running sales, finance, and so on.

The Office of the President is an attempt to convert top management into a doubles tennis team—made necessary (or, at least, possible) by the advent of information.

Traditionally, work on new products was done in a baseball-type team in which each function (design, engineering, manufacturing, marketing) did its own work, and then passed it on to the next.

In some major American industries, for example, pharmaceuticals or chemicals, this was changed long ago into the soccer or symphony orchestra type of team.

But the American automobile industry retained a baseball-type team structure for the design and introduction of new automobiles.

Around 1970, the Japanese began to use information to switch to a soccer-type team for this work.

As a result, Detroit fell way behind both in the speed with which it introduced new models and in its flexibility.

Since 1980, Detroit has been trying desperately to catch up with the Japanese by changing the design and introduction of new automobiles to a soccer-type team.

And on the factory floor the availability of information—which makes possible, in fact mandatory, the shift to “Total Quality Management”—is forcing Detroit to change from the baseball team, along which the traditional assembly line had been organized, to the doubles tennis team, which is the concept underlying “flexible manufacturing.”

Only when the appropriate type of team has been chosen and established will work on the productivity of knowledge workers and service workers become truly effective.

The right team by itself does not guarantee productivity.

But the wrong team destroys productivity.

1 {On various teams, and especially on the analogy between teams in business and teams in sports, see Robert W. Keidel, Game Plans (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1985).}

2 ☨ {On this, see also the discussion of the top management job in my Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices (1973).}

3 ♰ {See The New Realities, Chapter 14.}

The Need to Concentrate

Concentration on job and task is the last prerequisite for productivity in knowledge and service work.

In the work on making and doing things, the task is clearly defined.

The worker shoveling sand, whose task Taylor studied a century ago, was not expected to bring the sand to where he could begin shoveling it.

That was somebody else’s job.

The farmer plowing the field does not climb off the tractor to attend a meeting.

In machine-paced work, the machine concentrates the worker; the worker is servant to the machine.

In knowledge work and in most service work, where the machine (if any) is a servant to the worker, productivity requires the elimination of whatever activities do not contribute to performance.

They sidetrack and divert from performance.

Eliminating such work may be the single biggest step toward greater productivity in both knowledge and service work.

The task of nurses in hospitals is patient care.

But every study, shows that they spend up to three quarters of their time on work, that does not contribute to patient care.

Instead, two thirds or, three quarters of the nurse’s time is typically spent filling out papers.

Whenever we analyze the performance of salespeople in the department store, we find that they spend more than halt their time on work that does not contribute to their performance, that is, satisfying the customer.

They spend at least half their time filling out papers that serve the computer rather than the customer.

Whenever we analyze the time spent by engineers, we find that half their time is spent attending meetings or polishing reports which have very little to do with their own task.

This not only destroys productivity; it also destroys motivation and pride.

Wherever a hospital concentrates paperwork and assigns it, to a floor clerk who does nothing else, nurses’ productivity doubles.

So does their contentment.

They then suddenly have time, for the work they are trained and hired for: patient care.

Similarly, both the productivity and satisfaction of salespeople in department stores shoot up overnight when the paperwork is taken out of their job and concentrated with a floor clerk.

And the same happens when engineers are relieved of their “chores”—draftsman’s work, rewriting reports and memos, or attending meetings.

Knowledge workers and service workers should always be asked: “Is this work necessary to your main task?

Does it contribute to your performance?

Does it help you do your own job?”

And if the answer is no, the procedure or operation must be considered a “chore” rather than “work.”

It should either be dropped altogether or engineered into a job of its own.

Defining performance; determining the appropriate work flow; setting up the right team; and concentrating on work and achievement are prerequisites for productivity in knowledge work and service work.

Only when they have been done can we begin the work on making productive the individual job and the individual task.

Frederick Winslow Taylor is usually criticized for not asking the workers how to do the job.

He told them.

But so did George Elton Mayo (1880-1949), the Australian-born Harvard psychologist who in the 1920s and 1930s attempted to replace Taylor’s “Scientific Management” with “Human Relations.”

Lenin and Stalin did not consult the “masses,” either; they told them.

Freud never asked patients what they thought their problem might be.

And only toward the end of World War II did it occur to any high command to consult the users—the soldiers in the field—before introducing a new weapon.

The nineteenth century believed in the expert knowing the answers.

By now we have learned that those who actually do a job know more about it than anybody else.

They may not know how to interpret their knowledge, but they do know what works and what doesn’t.

And so, in the last forty years, we have learned that work on improving any job or task begins with the people who actually do the work.

They must be asked: “What can we learn from you?

What do you have to tell us about the job and how it should be done?

What tools do you need?

What information do you need?”

Workers must be required to take responsibility for their own productivity, and to exercise control over it.

We were first taught this lesson by American production in World War II.*1

But, as is well known, the Japanese were the first ones to apply the idea (if only because a few Americans, especially Edwards Deming and Joseph Juran, taught it to them).

After World War II, however, the United States, Great Britain, and Continental Europe all went back to the traditional “productivity by command” approach—largely as a result of strong labor union opposition to anything that would give the worker a “managerial attitude,” let alone “managerial responsibility.”

Only in the last ten years has American management rediscovered the lesson of its own performance in World War II.

In making and moving things, partnership with a responsible worker is the best way.

But Taylor’s telling them worked, too, and quite well.

In knowledge and service work, partnership with the responsible worker is the only way to improve productivity.

Nothing else works at all.

«§§§»

Productivity in knowledge work and service work demands that we build continuous learning into the job and into the organization.

Knowledge demands continuous learning because it is constantly changing.

But service work, even of the purely clerical kind, also demands continuous self-improvement, continuous learning.

The best way for people to learn how to be more productive is for them to teach.

To obtain the improvement in productivity which the post-capitalist society now needs, the organization has to become both a learning and a teaching organization.

1 { My two books The Future of Industrial Man (1942) and The New Society (1949), were the first to draw this conclusion from the World War II experience.

In them, I argued for the “responsible worker” taking “managerial responsibility.”

As a result of their wartime experiences, W. Edwards Deming and Joseph Juran each developed what we now call “Quality Circles” and “Total Quality Management.”

Finally, the idea was forcefully presented by Douglas McGregor in his well-known book The Human Side of Enterprise (New York McGraw-Hill, 1960), with his “Theory X” and “Theory Y.”}

Restructuring Organizations

Improving the productivity of knowledge workers and service workers will demand fundamental changes in the structure of organizations.