Marketing

There is a lot of confusion, misinformation and alternate views on marketing. Much of this comes from people looking through the rear view mirror with an inside-out approach (“Hey mister, want to buy a good watch?”).

“To know something,

to really understand something important,

one must look at it from sixteen different angles.

People are perceptually slow,

and there is no shortcut to understanding;

it takes a great deal of time.” read more

Druckerisms — attention-directing thought jewels from PFD

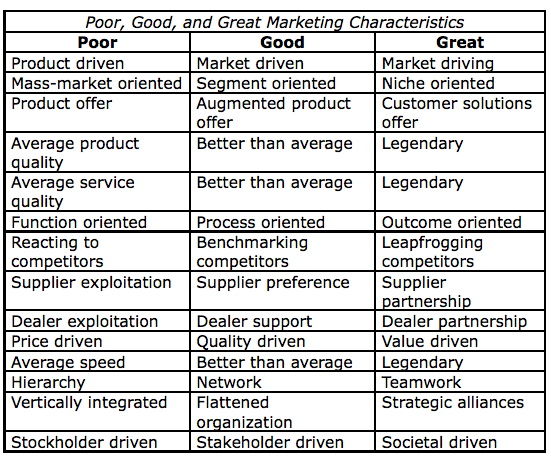

Marketing driven or Market driven?

A marketing-driven organization is run by the Marketing department.

It revolves around what marketers do.

A market-driven organization is driven by what the market wants, regardless of what the marketing department feels like doing.

(And of course, there are organizations driven by Sales, by Shareholder Relations and by Operations and Tech too.

Even a few that seem to be run by the Employee-happiness Department.

Not many, though.

Even in these organizations, the option remains: you can be market driven instead.

The first step is to choose your market…)

Seth Godin

Who are your customers?

Answering, “anyone who pays us money,” is a cop out. Answering, “anyone who pays us money,” is a cop out.

Almost as bad is describing your customers by demographics. Almost as bad is describing your customers by demographics.

It’s only a little interesting to know that they are, on average, 32 year old, white, male, lacrosse fans.

No, what we need to know is: No, what we need to know is:

What do they believe? What do they believe?

Who do they trust? Who do they trust?

What are they afraid of and who do they love? What are they afraid of and who do they love?

What are they seeking? What are they seeking?

Who are their friends? Who are their friends?

What do they talk about? What do they talk about?

Seth Godin

See “The Customer: Joined at the Hip” in The Definitive Drucker

A view from Peter Drucker mentor and ecologist

What executives should remember

… It should have been obvious from the beginning that management and entrepreneurship are only two different dimensions of the same task — that task is Part II: Business Performance.

An entrepreneur who doesn’t learn how to manage will not last long.

A management that does not learn to innovate will not last long.

Every institution—and not only business—must build into its day-to-day management four entrepreneurial activities that run in parallel.

One is the organized abandonment of products, services, processes, markets, distribution channels and so on that are no longer an optimal allocation of resources.

This is the first entrepreneurial discipline in any given situation.

Then any institution must organize for systematic, continuing improvement (what the Japanese call kaizen).

Then it has to organize for systematic and continuous exploitation, especially of its successes.

It has to build a different tomorrow on a proven today.

And, finally, it has to organize systematic innovation, that is, to create the different tomorrow that makes obsolete and, to a large extent, replaces even the most successful products of today in any organization.

Purposeful Innovation

Innovation in the existing organization requires special effort

Network society

I emphasize that these disciplines are not just desirable, they are three conditions for survival today.

… and they destabilize a community

These entrepreneurial tasks differ from the more conventional management roles of allocating present-day resources to present-day demands.

These entrepreneurial activities start with the outside and are focused on the outside.

But the tools we originally fashioned to bring the outside to the inside have all been penetrated by the inside focus of management.

They have turned into tools to enable management to ignore the outside.

Even worse, they are used to make management believe it can manipulate the outside and turn it to the organization’s purpose.

Take marketing

The term was coined 50 years ago to emphasize that the purpose and results of a business lie entirely outside of itself.

Marketing teaches that organized efforts are needed to bring an understanding of the outside, of society, economy and customer, to the inside of the organization and to make it the foundation for strategy and policy.

Yet marketing has rarely performed that grand task.

Instead it has become a tool to support selling.

It does not start out with “who is the customer?” but “what do we want to sell?”

It is aimed at getting people to buy the things that you want to make.

That’s getting things backward.

American industry lost the fax machine business that way.

The question should be “how can I make things the customers want to buy.”

Executives of any large organization—whether business enterprise, Roman Catholic diocese, university, health care institution, government agency—are woefully ignorant of the outside, as everybody knows who has worked with decisions in a large organization.

These executives must spend too much of their time and energy managing inwardly rather than managing outwardly.

The inward focus of management has been aggravated rather than alleviated in the last decades by the rise of information technology.

Information technology so far may well have done serious damage to management because it is so good at getting additional information of the wrong kind.

Based upon the 700-year-old accounting system designed to record and report inside data, information technology produces more data about the inside.

It produces practically no information about anything that goes on outside of the enterprise.

Practically every conference on information deals exclusively with how to get more inside data.

I have yet to hear of one that even raises the question: “What outside data do we need, and how do we get them?”

Management does not need more information about what is happening inside.

It needs more information on what is happening outside.

So far no one has figured out how to get meaningful outside data in any systematic form.

When it comes to outside data, we are still very largely in the anecdotal stage.

It can be predicted that the main challenge to information technology in the next 30 years will be to organize the systematic supply of meaningful outside information.

It is understandable that management began as a concern for the inside.

When the first large, modern organizations first arose—around 1870—the first and by far the most visible need was to organize the enterprise itself.

Nobody had ever done it before on that scale.

But now we know how to do that.

Growth and survival both now depend on getting the organization in touch with the outside world.

Management has become an external, not an internal, task.

For results take place outside the organization.

Inside, there are only costs.

The links below provide a view of the marketing landscape. Pick your poison. Whatever your area of interest, don't forget about managing oneself.

Changing Values and Characteristics

From chapter 19 of Innovation and Entrepreneurship by Peter Drucker

Amazon link: Innovation and Entrepreneurship

In the entrepreneurial strategies discussed so far, the aim is to introduce an innovation.

In the entrepreneurial strategy discussed in this chapter, the strategy itself is the innovation.

The product or service it carries may well have been around a long time—in our first example, the postal service, it was almost two thousand years old.

But the strategy converts this old, established product or service into something new.

It changes its utility, its value, its economic characteristics.

While physically there is no change, economically there is something different and new.

All the strategies to be discussed in this chapter have one thing in common.

They create a customer — and that is the ultimate purpose of a business, indeed, of economic activity.

As was first said more than thirty years ago in my The Practice of Management (New York: Harper & Row, 1954).

But they do so in four different ways:

by creating utility by creating utility

by pricing by pricing

by adaptation to the customer’s social and economic reality by adaptation to the customer’s social and economic reality

by delivering what represents true value to the customer by delivering what represents true value to the customer

... snip, snip ...

These examples are likely to be considered obvious.

Surely, anybody applying a little intelligence would have come up with these and similar strategies?

But the father of systematic economics, David Ricardo, is believed to have said once, “Profits are not made by differential cleverness, but by differential stupidity.”

The strategies work, not because they are clever, but because most suppliers—of goods as well as of services, businesses as well as public-service institutions—do not think.

They work precisely because they are so “obvious.”

Why, then, are they so rare?

For, as these examples show, anyone who asks the question, What does the customer really buy? will win the race.

In fact, it is not even a race since nobody else is running.

What explains this?

One reason is the economists and their concept of “value.”

Every economics book points out that customers do not buy a “product,” but what the product does for them.

And then, every economics book promptly drops consideration of everything except the “price” for the product, a “price” defined as what the customer pays to take possession or ownership of a thing or a service.

What the product does for the customer is never mentioned again.

Unfortunately, suppliers, whether of products or of services, tend to follow the economists.

It is meaningful to say that “product A costs X dollars.”

It is meaningful to say that “we have to get Y dollars for the product to cover our own costs of production and have enough left over to cover the cost of capital, and thereby to show an adequate profit.”

But it makes no sense at all to conclude and therefore the customer has to pay the lump sum of Y dollars in cash for each piece of product A he buys.”

Rather, the argument should go as follows: “What the customer pays for each piece of the product has to work out as Y dollars for us.

But how the customer pays depends on what makes the most sense to him.

It depends on what the product does for the customer.

It depends on what fits his reality.

It depends on what the customer sees as ‘value.’”

Price in itself is not “pricing,” and it is not “value.”

It was this insight that gave King Gillette a virtual monopoly on the shaving market for almost forty years; it also enabled the tiny Haloid Company to become the multibillion-dollar Xerox Company in ten years, and it gave General Electric world leadership in steam turbines.

In every single case, these companies became exceedingly profitable.

But they earned their profitability.

They were paid for giving their customers satisfaction, for giving their customers what the customers wanted to buy, in other words, for giving their customers their money’s worth.

“But this is nothing but elementary marketing,” most readers will protest, and they are right.

It is nothing but elementary marketing.

To start out with the customer’s utility, with what the customer buys, with what the realities of the customer are and what the customer’s values are—this is what marketing is all about.

But why, after forty years of preaching Marketing, teaching Marketing, professing Marketing, so few suppliers are willing to follow, I cannot explain.

The fact remains that so far, anyone who is willing to use marketing as the basis for strategy is likely to acquire leadership in an industry or a market fast and almost without risk.

Entrepreneurial strategies are as important as purposeful innovation and entrepreneurial management.

Together, the three make up innovation and entrepreneurship.

The available strategies are reasonably clear, and there are only a few of them.

But it is far less easy to be specific about entrepreneurial strategies than it is about purposeful innovation and entrepreneurial management.

We know what the areas are in which innovative opportunities are to be found and how they are to be analyzed.

There are correct policies and practices and wrong policies and practices to make an existing business or public-service institution capable of entrepreneurship; right things to do and wrong things to do in a new venture.

But the entrepreneurial strategy that fits a certain innovation is a high-risk decision.

Some entrepreneurial strategies are better fits in a given situation, for example, the strategy that I called entrepreneurial judo, which is the strategy of choice where the leading businesses in an industry persist year in and year out in the same habits of arrogance and false superiority.

We can describe the typical advantages and the typical limitations of certain entrepreneurial strategies.

Above all, we know that an entrepreneurial strategy has more chance of success the more it starts out with the users—their utilities, their values, their realities.

An innovation is a change in market or society.

It produces a greater yield for the user, greater wealth-producing capacity for society, higher value or greater satisfaction.

The test of an innovation is always what it does for the user.

Hence, entrepreneurship always needs to be market-focused, indeed, market-driven.

Still, entrepreneurial strategy remains the decision-making area of entrepreneurship and therefore the risk-taking one.

It is by no means hunch or gamble.

But it also is not precisely science.

Rather, it is judgment.

What do customers value?

The question, What do customers value?—what satisfies their needs, wants, and aspirations—is so complicated that it can only be answered by customers themselves.

And the first rule is that there are no irrational customers.

Almost without exception, customers behave rationally in terms of their own realities and their own situation. (Their logic bubble — see below)

Leadership should not even try to guess at the answers but should always go to the customers in a systematic quest for those answers.

I practice this.

Each year I personally telephone a random sample of fifty or sixty students who graduated ten years earlier.

I ask, “Looking back, what did we contribute in this school?

What is still important to you?

What should we do better?

What should we stop doing?”

And believe me, the knowledge I have gained has had a profound influence.

What does the customer value? may be the most important question.

Yet it is the one least often asked.

Nonprofit leaders tend to answer it for themselves.

“It’s the quality of our programs.

It’s the way we improve the community.”

People are so convinced they are doing the right things and so committed to their cause that they come to see the institution as an end in itself.

But that’s a bureaucracy.

Instead of asking, “Does it deliver value to our customers?” they ask, “Does it fit our rules?”

And that not only inhibits performance but also destroys vision and dedication.

— Peter Drucker,

The Five Most Important Questions …

Quality

Quality in a product or service is not what the supplier puts in.

It is what the customer gets out and is willing to pay for.

A product is not quality because it is hard to make and costs a lot of money, as manufacturers typically believe.

This is incompetence.

Customers pay only for what is of use to them and gives them value.

Nothing else constitutes quality.

— Peter Drucker

The Logic Bubble

I (Edward de Bono) created the term ‘logic bubble’ in a previous book.

When someone does something you do not like or with which you do not agree, it is easy to label that person as stupid, ignorant or malevolent.

But that person may be acting ‘logically’ within his or her ‘logic bubble’.

That bubble is made up of the perceptions, values, needs and experience of that person.

If you make a real effort to see inside that bubble and to see where that person is ‘coming from’, you usually see the logic of that person’s position.

In the school programme for teaching thinking (CoRT (Cognitive Research Trust) programme) there are tools which broaden perception so the thinker sees a wider picture and acts accordingly.

One of these tools is OPV, which encourages the thinker to ‘see the Other Person’s Point of View’.

We have numerous examples where a serious fight came to a sudden end when the combatants (who had learned the methods) decided to do an OPV on each other, a very similar process to understanding the ‘logic bubble’ of the other party.

— Edward de Bono

Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything (P.S.)

Communications

From The Daily Drucker

Consumerism is the "shame of marketing."

Despite the emphasis on marketing and the marketing approach, marketing is still rhetoric rather than reality in far too many businesses.

"Consumerism" proves this.

For what consumerism demands of business is that it actually market.

It demands that business start out with the needs, the realities, the values of the customer.

It demands that business define its goal as the satisfaction of customer needs.

It demands that business base its reward on its contribution to the customer.

That after years of marketing rhetoric consumerism could become a powerful popular movement proves that not much marketing has been practiced.

Consumerism is the "shame of marketing."

And in marketing one does not begin with the question, "What do we want?"

One begins with the question, "What does the other party want?

What are its values?

What are its goals?

What does it consider results?"—Peter Drucker

From a Class with Drucker

"Marketing and selling are not identical."

Then he went on to really wake me up.

"Selling and marketing are neither synonymous nor complementary," he said.

"One could consider them adversarial in some cases.

There is no doubt that if marketing were done perfectly, selling, in the actual sense of the word, would be unnecessary" What was Peter saying?

He had me.

I listened on.

According to Drucker, it was the Japanese who invented real marketing, and not in this century either, but back in the 1600's.

A merchant with a different retailing concept came to Tokyo from out in the boondocks and opened what today we would term a retail outlet.

Moreover, this merchant had a revolutionary concept of selling.

Previously, all selling was done by sellers who made or grew what they sold, whether it was food, clothing, or fighting equipment.

Drucker said that this new merchant was different in two ways.

First, he didn't sell a single class of goods.

He sold all kinds of goods.

Second, he didn't create what he sold.

He bought goods from others who had created them.

Just like Sears, Macy's, or Wal-Mart today, he saw himself as being a buying agent for what his customers wanted.

Consequently, this retailer saw his task not of persuading others to purchase a product which he had already had on hand and therefore must sell, but rather in discovering first what his customers wanted and then getting these desired products from others for resale.

… snip, snip …

Drucker went on to explain that marketing was more than just an important business function.

In fact, he said it wasn't a business function at all, but rather the basis of any business.

It was a mistake to consider marketing on an equal basis with other functionary areas such as manufacturing, because marketing permeated every aspect of the business.

He continued that marketing's importance was at last recognized when companies began to add marketing departments to their organizations.

However, Peter pointed out that, although many corporations agreed with "the marketing concept," which primarily emphasized the customer and paid lip service to it, in practice many, if not most, companies ignored this reality.

Drucker said that companies struggled to adopt the marketing concept organizationally in several ways.

Some companies added a separate department which was responsible for either marketing research or marketing strategy, but they really functioned as staff to top management, production divisions, or a separate sales division.

Others combined marketing and sales into a single department; sometimes with marketing in charge, sometimes with sales in charge.

Few companies gave much thought to the idea of the basic marketing concept as driving the business, which was far more important.

According to Drucker, this concept would drastically challenge the position of marketing in many companies, despite the considerable evidence that this was clearly what should happen.

In Drucker's view, marketing drove the business and needed authority in a business to market correctly.

From Managing in the Next Society

We know literally nothing about the outside, and yet, even if you are the leading business in an industry, the great majority of the people who buy your kind of product or services are not your customers.

If you have 30 percent of the market, you are the giant.

But that means that 70 percent of the customers do not buy your product or your services, and we know nothing about them.

These “noncustomers” are particularly important because they represent a source of information that can help you gauge the changes that will affect your industry.

How so?

If you look at the changes in major industries over the last forty years, you’ll see that practically all of them occurred outside the existing market, or product, or technology.

Whatever the business, senior people need to spend more time outside their own shop.

There is no question that getting to know your noncustomers is far from easy, but it really is the only way to expand your knowledge.

The people I know, for example, who have been successful building their business in Japan made a point of studying Japanese history before making contact.

We are fortunate in the United States because of our cultural diversity—and we should use that asset to our advantage.

In the nineteenth century, you could take for granted that each major industry spawned a specific technology, and that technologies from separate industries would never meet.

This is the hypothesis on which all the great research labs have been founded, beginning with Siemens in Germany in 1869.

That assumption no longer works.

Technologies now crisscross each other all the time, and productivity is no guarantee of achievement.

In the last thirty years, Bell Laboratories has been more productive than at any other time in its history—but what is its track record during this period for major technological breakthroughs?

There is no question that businesses need to understand what goes on outside their spheres.

But so far there is almost no information—and what little exists is at best anecdotal.

We’re only beginning to learn how to quantify this information.

So far, whenever anyone claims to have done so, I know that somebody has put a thumb on the scale.

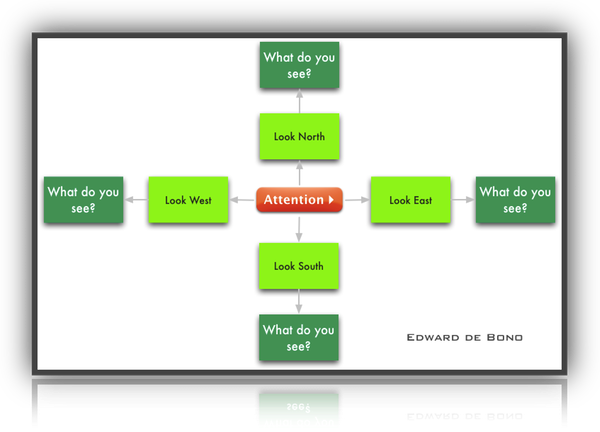

Attention: Look north, look south …

Four definitions of marketing (by Peter Drucker). Four definitions of marketing (by Peter Drucker).

Four marketing lessons for the future in Managing for the Future Four marketing lessons for the future in Managing for the Future

Learning From Foreign Management in The Changing World of the Executive Learning From Foreign Management in The Changing World of the Executive

Third, foreign managers take marketing seriously.

In most American companies marketing still means no more than systematic selling.

Foreigners today have absorbed more fully the true meaning of marketing: knowing what is value for the customer.

American managers can learn from the way foreigners look at their products, technology, and strategies from the point of view of the market rather than vice versa.

Foreigners are increasingly thinking in terms of market structure, trying to define specific market niches for their products, and designing their businesses with a marketing strategy in mind.

The Japanese automobile companies are only one example.

Few companies are as attentive to the market as the high-technology and high-fashion entrepreneurs of northern Italy.

It is not correct, as is so often asserted in this country, that Japanese and Western European businesses subordinate profits.

Indeed, the return on total assets is conspicuously higher today in a great many foreign businesses than it is in this country, especially if profits are adjusted for inflation.

But the foreign manager has increasingly learned to say, “It is my job to earn a proper profit on what the market wants to buy.”

We still, by and large, try to say in this country, “What is our product with the highest profit margin?

Let’s try to sell that, and sell it hard.”

Incidentally, when the foreign manager says “market,” he tends to think of the world economy.

Very few Japanese companies actually depend heavily on exports.

And yet it is the rare Japanese business which does not start out with the world economy in marketing, even if its own sales are predominantly in the Japanese home market.

Management’s new paradigms Management’s new paradigms

From Analysis to Perception — The New Worldview From Analysis to Perception — The New Worldview

See "The Customer: Joined at the Hip" in The Definitive Drucker See "The Customer: Joined at the Hip" in The Definitive Drucker

Realities: Business; Markets; Knowledge; Efforts and Cost; Executive Realities: Business; Markets; Knowledge; Efforts and Cost; Executive

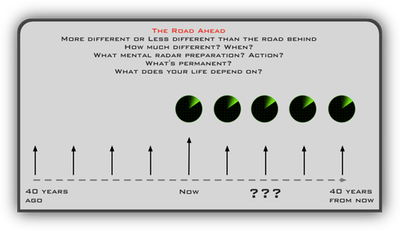

Marketing and Innovation in a society moving in time Marketing and Innovation in a society moving in time

See "Changing Values and Characteristics (creating a customer)" in Innovation and Entrepreneurship by Peter Drucker See "Changing Values and Characteristics (creating a customer)" in Innovation and Entrepreneurship by Peter Drucker

See "From mission to performance (effective strategies for marketing, innovation, and fund development)" in Managing the Nonprofit Organization See "From mission to performance (effective strategies for marketing, innovation, and fund development)" in Managing the Nonprofit Organization

The Five Most Important Questions You Will Ever Ask About Your Organization The Five Most Important Questions You Will Ever Ask About Your Organization

The Marketing Mystique (by Edward McKay) The Marketing Mystique (by Edward McKay)

Marketing Moves (by Phillip Kotler) Marketing Moves (by Phillip Kotler)

Marketing Management (by Phillip Kotler) Marketing Management (by Phillip Kotler)

Ted Levitt on Marketing Ted Levitt on Marketing

Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind by Al Ries and Jack Trout Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind by Al Ries and Jack Trout

Marketing Warfare by Al Ries and Jack Trout Marketing Warfare by Al Ries and Jack Trout

Bottom-Up Marketing by Al Ries and Jack Trout Bottom-Up Marketing by Al Ries and Jack Trout

22 Immutable Laws of Marketing 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing

David Ogilvy: Marketing, Advertising, Competing with Proctor & Gamble David Ogilvy: Marketing, Advertising, Competing with Proctor & Gamble

Made to Stick Made to Stick

Seth Godin Books at Amazon.com Seth Godin Books at Amazon.com

Relationship Marketing by Regis McKenna Relationship Marketing by Regis McKenna

Reality Check by Guy Kawasaki Reality Check by Guy Kawasaki

Guerrilla marketing series, sales, finance, and Immutable marketing laws Guerrilla marketing series, sales, finance, and Immutable marketing laws

Marketing Insights from A to Z—80 Concepts Every Manager Needs To Know by Philip Kotler. Marketing Insights from A to Z—80 Concepts Every Manager Needs To Know by Philip Kotler.

Chaotics: The Business of Managing and Marketing in the Age of Turbulence Chaotics: The Business of Managing and Marketing in the Age of Turbulence

For a practical example see the history segment of the Motorola page at Wikipedia For a practical example see the history segment of the Motorola page at Wikipedia

The following appeared in a November 2003 Internet posting: Motorola spinning off semiconductor business—Baffling. Does anyone but me find Motorola's announcement that it will spin off its semiconductor business a bit peculiar? How does a company manage to create and pioneer early markets, dominate, and then give up on the market? I'm talking about radios, TVs, and microprocessors, including RISC chips. When will the company bail on the cell-phone market it largely created? This is a weird business model. My advice to Motorola is to change the name to Motorola Market Development Company. It would make more sense.

2011 Follow-up: "Motorola Solutions Inc. and Motorola Mobility Holdings Inc., the two companies that split from each other this year, increased the pay of the chief executive officers who oversaw the separation …"

Organization Evolution ©

List of topics in this Folder

TLNKWMarketing

|

![]()