Management, Revised Edition

by Peter Drucker with Joseph A. Maciariello

Amazon Links: Management Rev Ed and Management Cases, Revised Edition and Management Cases, Revised Edition

Contents list for Management Cases, Revised Edition

“Management, in most business schools, is still taught as a bundle of techniques, such as the technique of budgeting.

To be sure, management, like any other work, has its own tools and its own techniques.

But just as the essence of medicine is not the urinalysis, important though it is, the essence of management is not techniques and procedures.

The essence of management is to make knowledge productive.

Management, in other words, is a social function.

And in its practice, management is truly a “liberal art.” ”

From “A Century of Social Transformation”

About management

… It also follows that managing a business must be a creative rather than an adaptive task.

The more a management creates economic conditions or changes them rather than passively adapts to them, the more it manages the business (same concept applies to non-business institutions)—Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices.

More on this theme in “Management”

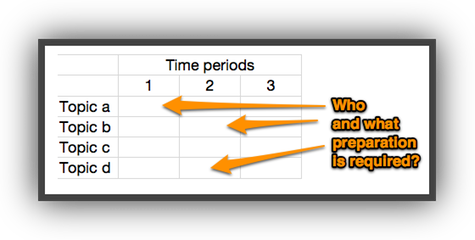

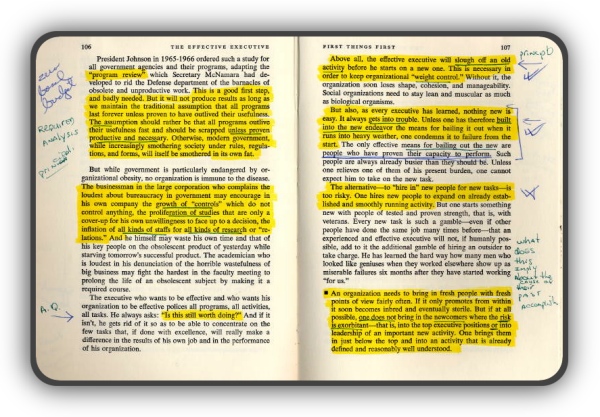

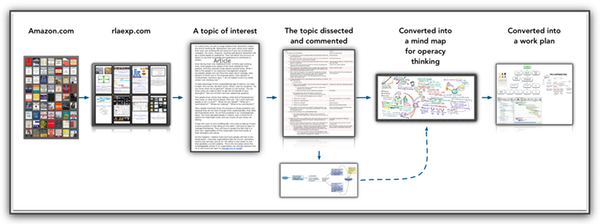

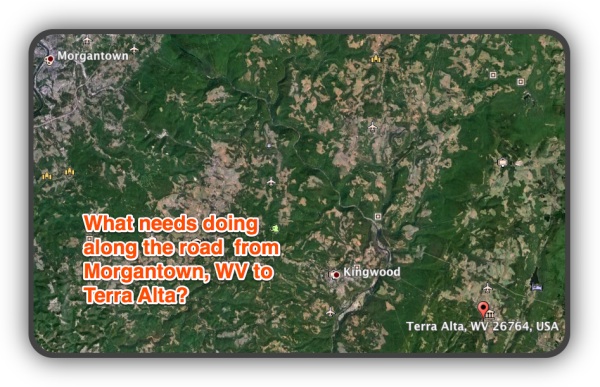

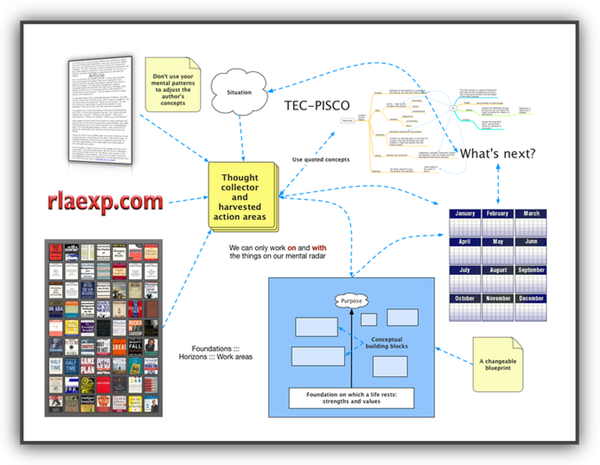

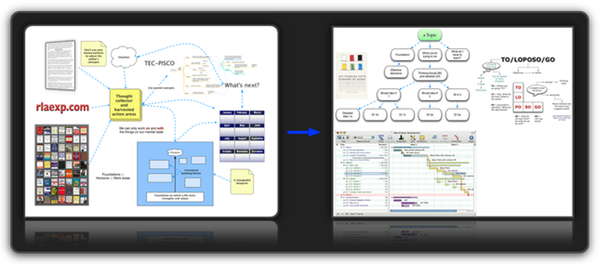

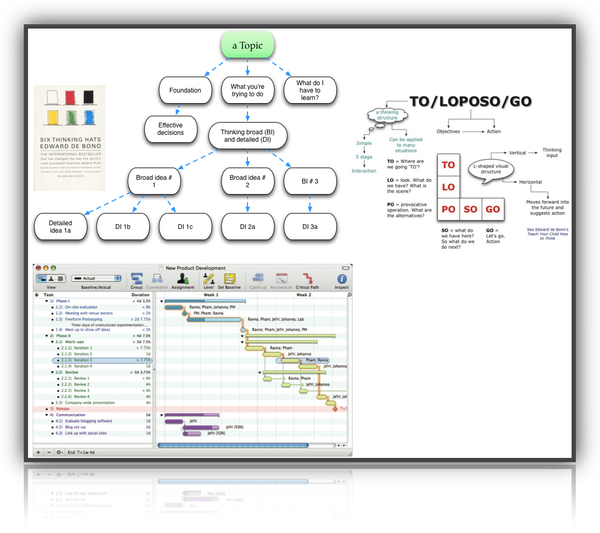

This is a WHAT TO DO book not “how to do it.”

It is not just for reading, but for doing—what and when at multiple points in the future.

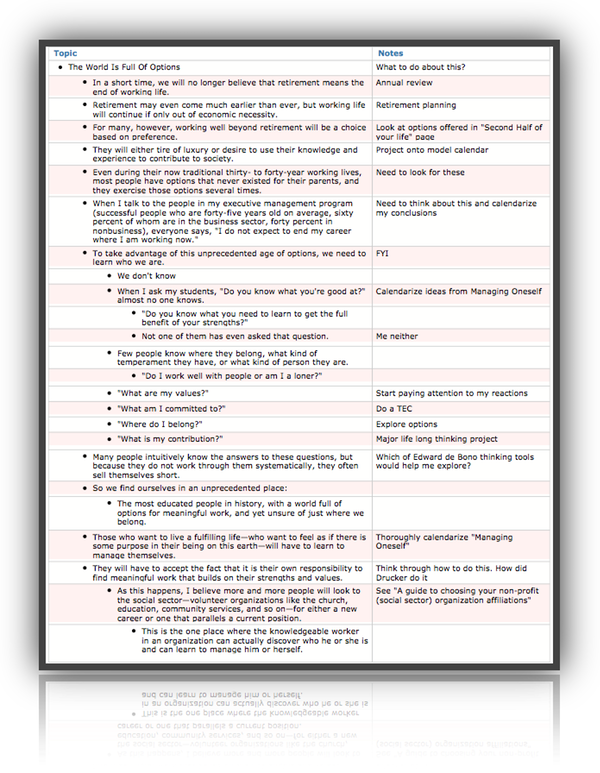

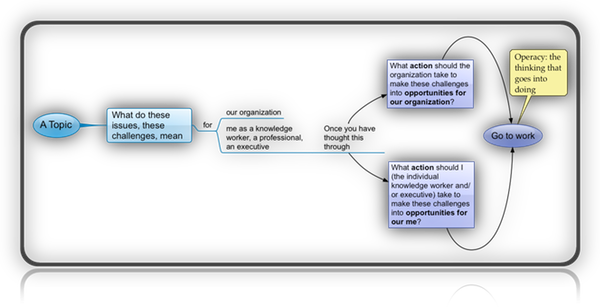

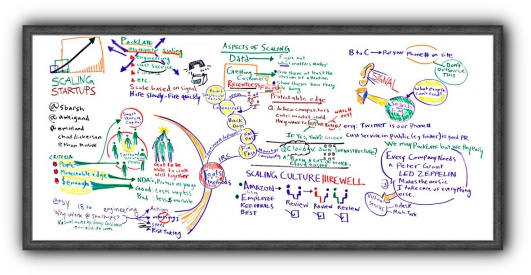

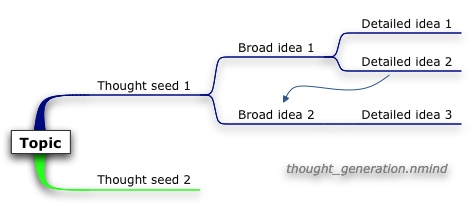

Information is not enough, thinking is needed and Thinking broad and Thinking detailed

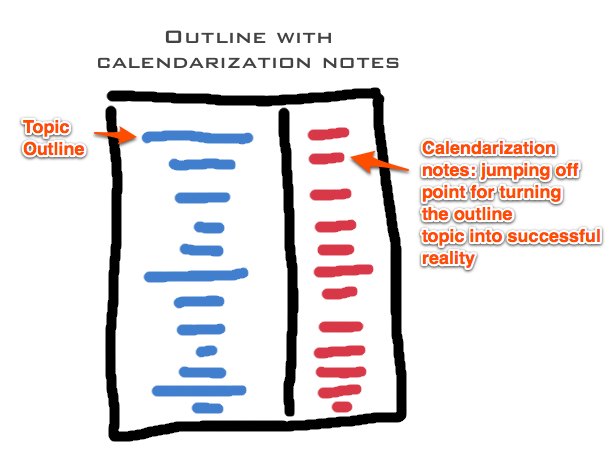

Don't memorize, calendarize

This book doesn’t offer fine-tuning tips and techniques to superimpose on an existing organization.

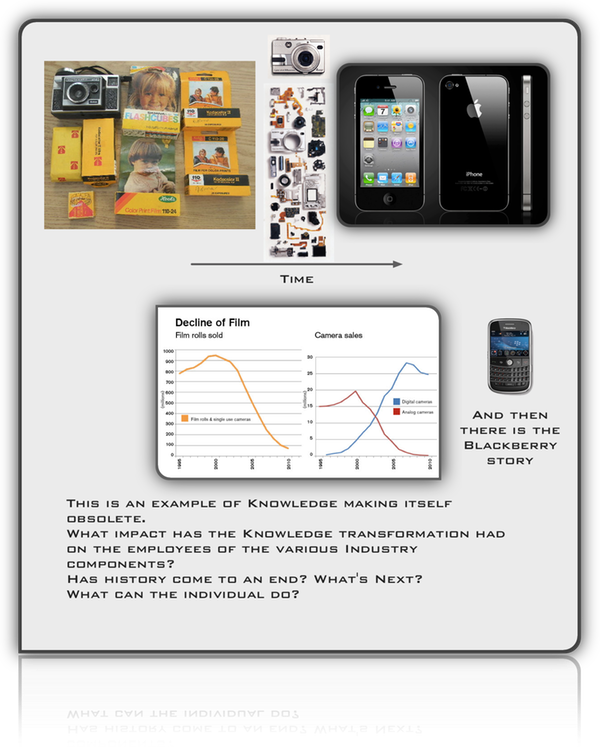

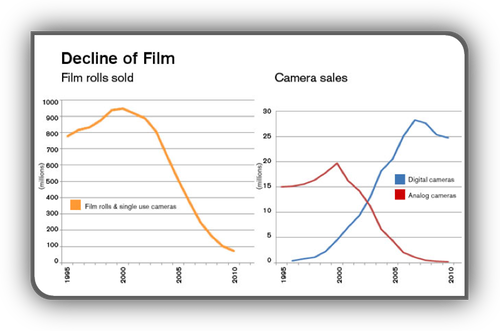

It is not about how to operate a better blacksmith or candle-making shop, run a railroad, or improve AT&T of the 1960s—that’s so yesterday.

All of the preceding are gone—and for a reason. They outlived their usefulness.

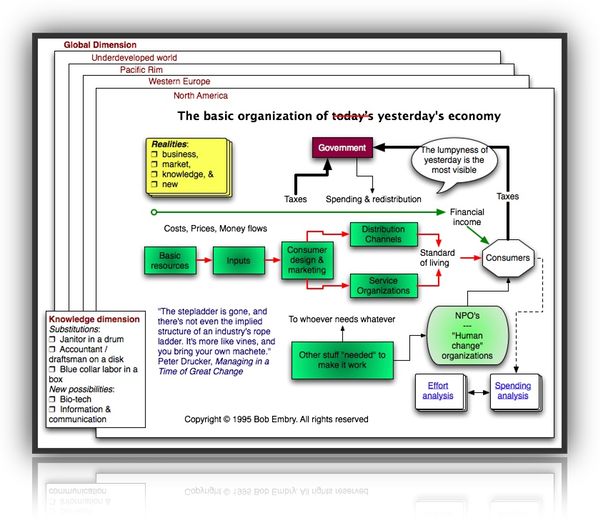

This book addresses being a core organization in a “society of organizations” moving in time.

This is a book about making a contribution to society—a contribution that matters at different points in the future.

The vacuum that many inside-out institutions filled no longer exists and they need to move on.

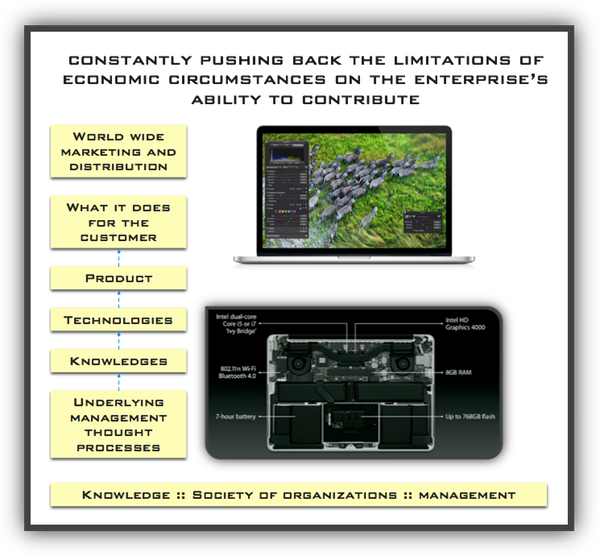

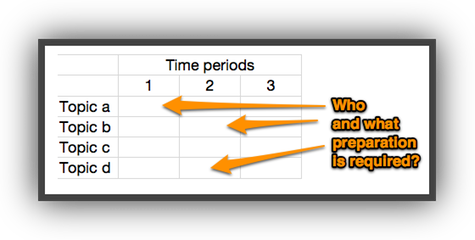

You might want to evaluate your performance level in each of the topic areas below.

Are you world-class?

Are you number 1 or 2 in the world?

Do you have world-class management practices?

What about tomorrowS?

What are the questions that you need to ask?

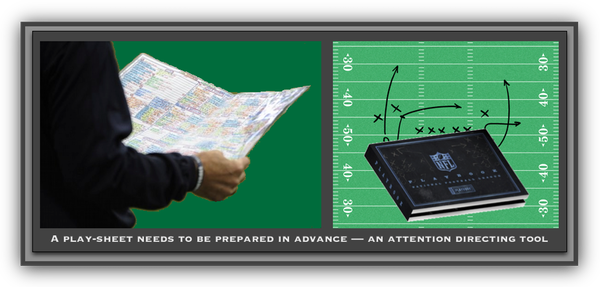

Good football coaches have a playbook—plays they have thought out in advance.

They also have a play sheet they carry along the side lines.

They have to use experience and judgement in which actual plays to use.

There has to be constant adjustment to the actual situation.

These ideas also apply in a society of organizations, but there are gigantic differences.

Unforeseen competitors and challenges can come from nowhere.

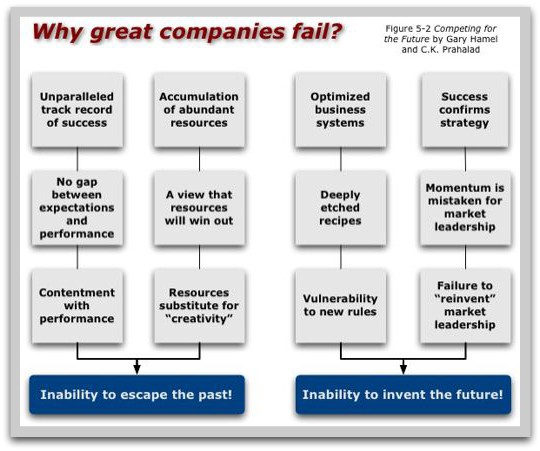

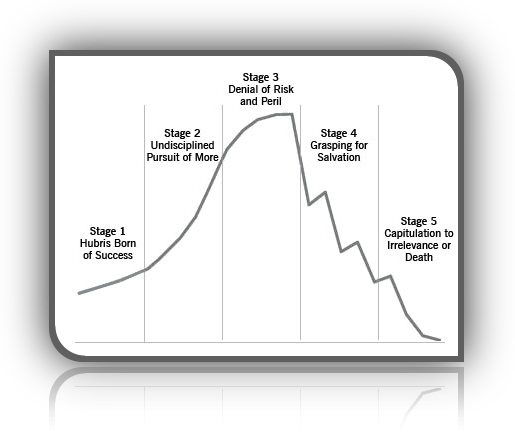

Victims of success Victims of success

How Hewlett-Packard Lost the HP Way (Three CEOs in six years, boardroom changes, and other contributers to disfunction) How Hewlett-Packard Lost the HP Way (Three CEOs in six years, boardroom changes, and other contributers to disfunction)

Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?: Leading a Great Enterprise (IBM) through Dramatic Change starting with their near bankruptcy. Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?: Leading a Great Enterprise (IBM) through Dramatic Change starting with their near bankruptcy.

Amazon link: How The Mighty Fall: And Why Some Companies Never Give In Amazon link: How The Mighty Fall: And Why Some Companies Never Give In

More economic landscape vistas

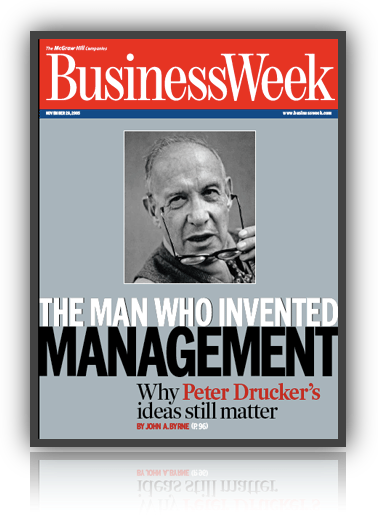

About Peter Drucker

Remembering Drucker (Four years after his death, Peter Drucker remains the king of the management gurus) from The Economist

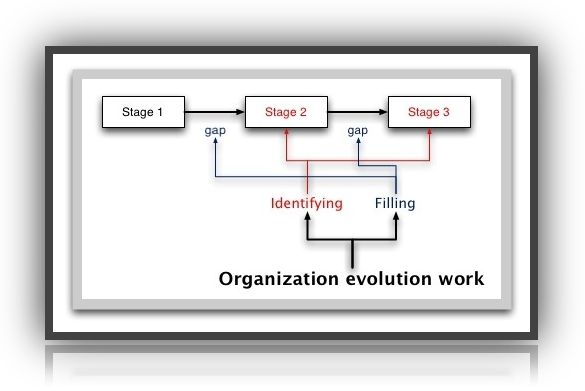

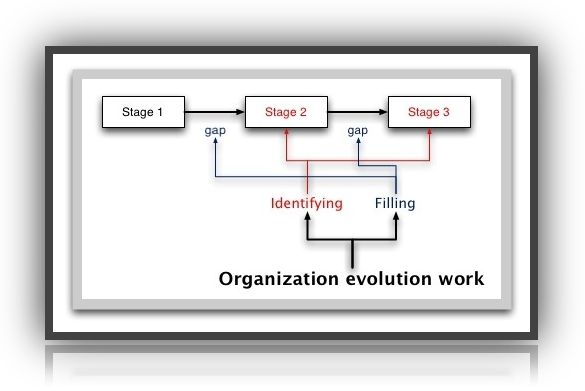

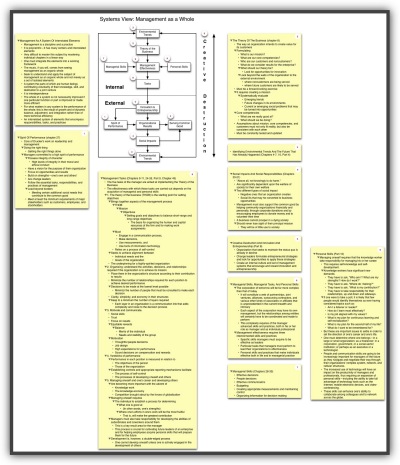

An operational work sequence is different from the chapter sequence.

Getting the right people on board ::: Effective decisions

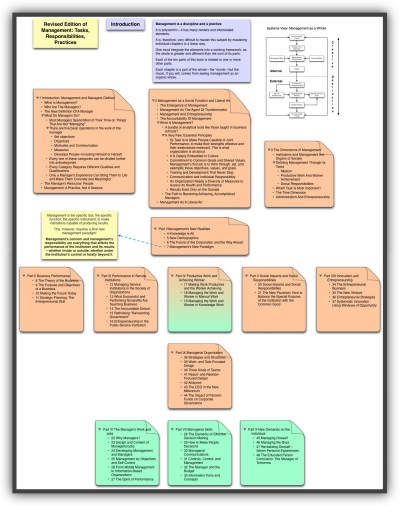

Contents of Revised Edition of Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices by Peter Drucker

Chapter summaries PDF

What thinking is needed to make this ↑ ↓ operational?

- Title & Copyright Information

- Peter Drucker most important contribution

- Contents

- Peter Drucker's Legacy (leadership etc.)

- Introduction to the Revised Edition of Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

- The Origins of This Book

- How To Use This Book

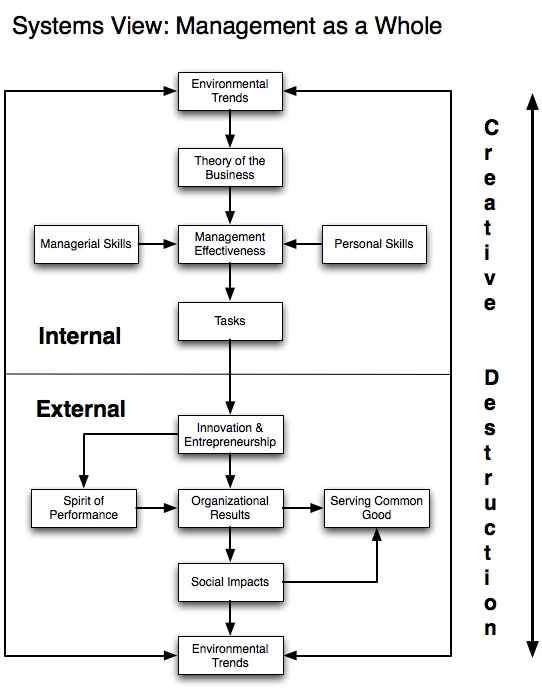

- Management As A System Of Interrelated Elements (Figure 1)

- The Spirit Of Performance (Chapter 27)

- The Theory Of The Business (Chapter 8)

- Identifying Environmental Trends And The Future That Has Already Happened (Chapters 4-7, 10, Part 4)

- Social Impacts And Social Responsibilities (Chapters 20-21)

- Creative Destruction And Innovation And Entrepreneurship (Part 8)

- Managerial Skills, Managerial Tasks, And Personal Skills

- Managerial Skills (Chapters 28-33)

- Effective managers make effective decisions

- People decisions are a special case of decision making requiring their own rules

- Remaining four areas of managerial skills that executives must acquire to carry out their tasks

- Managers must learn to be good communicators

- Budgeting is the most widely used tool of management

- Creating appropriate measurements and maintaining control

- Organizing information for decision making

- Management Tasks (Chapters 9-11, 24-26, Part 9, Chapter 45)

- The theory of the business & MBO

- Organizing

- A manager must also motivate and communicate

- Establish yardsticks of performance

- Managing oneself and one's career and developing others

- Personal Skills (Part 10)

- Summary

- Preface!!!!!

- 1 Introduction: Management and Managers Defined

- What Is Management?

- Who Are The Managers?

- The New Definition Of A Manager

- What Do Managers Do?

- Most Managers Spend Most of Their Time on Things That Are Not "Managing"

- There are five basic operations in the work of the manager

- Set objectives

- Organizes

- Motivates and Communicates

- Measures

- Develops People—Including Himself or Herself

- Every one of these categories can be divided further into subcategories

- Every Category Requires Different Qualities and Qualifications

- Only a Manager's Experience Can Bring Them to Life and Make Them Concrete and Meaningful

- The Manager's Resource: People

- Management: A Practice, Not A Science

- Note: The Roots And History Of Management

- The Early Economists

- The Emergence Of Large-Scale Organization

- The First Management Boom

- The Work Of The 1920s And 1930s

- Summary

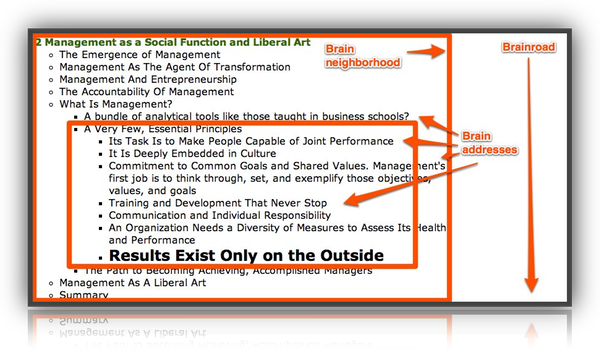

- 2 Management as a Social Function and Liberal Art

- The Emergence of Management

- Management As The Agent Of Transformation

- Management And Entrepreneurship

- The Accountability Of Management

- What Is Management?

- A bundle of analytical tools like those taught in business schools?

- A Very Few, Essential Principles

- Management is about human beings. Its task is to make people capable of joint performance, to make their strengths effective and their weaknesses irrelevant.

- It is deeply embedded in culture

- Commitment to common goals and shared values. Management's first job is to think through, set, and exemplify those objectives, values, and goals

- Training and development that never stop

- Communication and individual responsibility

- An organization needs a diversity of measures to assess its health and performance

- Results Exist Only on the Outside

- The Path to Becoming Achieving, Accomplished Managers

- Management As A Liberal Art

- Summary

- 3 The Dimensions of Management

- Institutions and Management Are Organs of Society

- Defining Management Through its Tasks

- Mission

- Productive Work And Worker Achievement

- Social Responsibilities

- Which Task Is Most Important?

- The Time Dimension

- Administration And Entrepreneurship

- Summary

- Part I: Management's New Realities

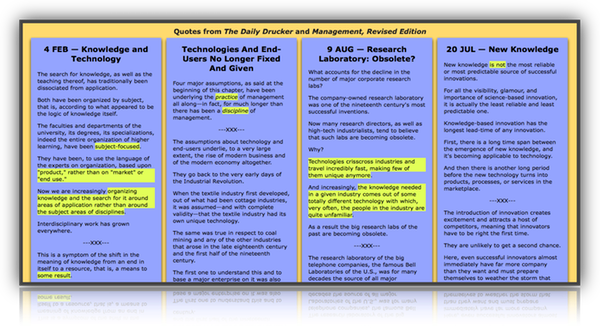

- 4 Knowledge Is All

- Knowledge Is the Key Resource in Society and Knowledge Workers Are the Dominant Group in the Workforce

- The Three Main Characteristics of (a/the) Knowledge Economy

- Borderlessness, because knowledge travels even more effortlessly than money.

- Upward mobility, available to everyone through easily acquired formal education.

- The potential for failure as well as success. Anyone can acquire the "means of production"—that is, the knowledge required for the job—but not everyone can win.

- The New Workforce

- The terms knowledge industries, knowledge work and knowledge worker are nearly fifty years old.

- They were coined around 1960, simultaneously but independently— the first by a Princeton economist, Fritz Machlup, the second and third by this writer.

- Now everyone uses them, but as yet hardly anyone understands their implications for human values and human behavior, for managing people and making them productive, for economics, and for politics.

- What is already clear, however, is that the emerging knowledge society and knowledge economy will be radically different from the society and economy of the late twentieth century

- His And Hers

- Ever Upward

- The Price Of Success

- Summary

- 5 New Demographics

- The Sifting Age Structure

- Needed But Unwanted

- A Country of Immigrants

- Splitting of Hitherto Homogeneous Societies and Markets

- The End of the Single Market

- Beware Demographic Changes

- Summary

- 6 The Future of the Corporation and the Way Ahead

- Five OUTDATED Basic Assumptions

- The corporation is the "master," the employee is the "servant."

- The great majority of employees work full-time for the corporation

- All activities under one management

- Suppliers have market power

- Technologies and industries are a unique set

- Everything In Its Place (Five NEW Assumptions)

- The means of production is knowledge, which is owned by knowledge workers and is highly portable

- A growing number of people who work for an organization will not be full-time employees

- There always were limits to the importance of transactional costs

- The customer now has the information

- There are few unique technologies anymore

- Who Needs A Research Lab?

- The Next Company

- From Corporation To Confederation

- General Motors Example

- The Toyota Way

- A Large Manufacturer of Branded and Packaged Consumer Goods

- There Are Already a Good Many Variations on This Theme

- The Syndicate Model

- Top management's role

- Life At The Top

- The Way Ahead: The Time To Get Ready For The New Realities Is Now

- The future corporation

- People policies

- Outside information

- Change agents

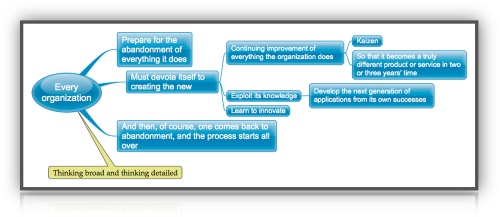

- To survive and succeed, every organization will have to turn itself into a change agent.

- The most effective way to manage change successfully is to create it.

- But experience has shown that grafting innovation onto a traditional enterprise does not work.

- The enterprise has to become a change agent.

- This requires the organized abandonment of things that have been shown to be unsuccessful …

- The organized and continuous improvement of every product, service, and process within the enterprise (which the Japanese call kaizen).

- It requires the exploitation of successes, especially unexpected and unplanned-for ones

- It requires systematic innovation.

- The point of becoming a change agent is that it changes the mindset of the entire organization.

- Instead of seeing change as a threat, its people will come to consider it as an opportunity.

- And Then?

- Information revolution in historical context

- The two industrial revolutions also bred new theories and new ideologies

- Big Ideas

- New Economic Regions

- Transnational financial organizations

- Schumpeter's postulates of dynamic disequilibrium

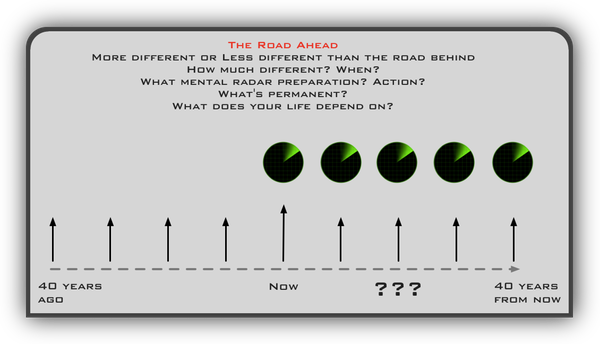

- The World of 2030: very different

- Summary

- 7 Management's New Paradigm

- Introduction (About Assumptions)

- Management Is Business Management — NOT!

- The One Right Organization — NOT!

- The One Right Way To Manage People — NOT!

- Technologies And End-Users Are Fixed And Given — NOT!

- Management's Scope Is Legally Defined — NOT!

- Management's Scope Is Politically Defined — NOT!

- The Inside Is Management's Domain — NOT!

-

Final paradigm: Management's Concern and Responsibility — Management is the specific tool, the specific function, the specific instrument, to make institutions capable of producing results (on the outside).

This, however, requires a final new management paradigm:

Management's concern and management's responsibility are everything that affects the performance of the institution and its results — whether inside or outside, whether under the institution's control or totally beyond it. (core work toward — calendarize this?)

- Summary

- Part II: Business Performance

- 8. The Theory of the Business PDF (in depth)

- 9 The Purpose and Objectives of a Business PDF

- The failure to understand the nature, function, and purpose of business enterprise

- To know what a business is, we have to start with its purpose

- Its purpose must lie outside of the business itself

- In fact, it must lie in society, since business enterprise is an organ of society.

- There is only one valid definition of business purpose: to create a customer

- It is the customer who determines what a business is

- The Purpose Of A Business

- Two basic functions: marketing and innovation (it ain't what you think)

- The reality of today's organization

- What is Our Business? (Product and service names are not allowed. We're in the computer, airline, banking or retailing business misses the point. It doesn't define a specific contribution)

- Who is the Customer is the Starting Point

- Where is the customer?

- What does the customer buy?

- When to ask: What is our business?

- And what will it be?

- "What Should Our Business Be?"

- Planned, systematic abandonment

- Systematic analysis of all existing products, services …

- Defining the purpose and mission enables a business to be managed for performance

- The basic definition of the business and of its purpose and mission have to translated into objectives

- Objectives must be derived from "what our business is, what it will be, and what it should be." (Product and service names are not allowed. We're in the computer, airline, banking or retailing business misses the point. It doesn't define a specific contribution)

- Objectives must be operational

- Objectives must make possible concentration of resources and efforts

- There must be multiple objectives rather than a single objective

- Objectives are needed in all areas on which the survival of the business depends

- Areas that need objectives

- Objectives are the basis for work and assignments

- Objectives are always needed in all eight key areas

- Measurements are needed in all areas (see chapter 31 — Controls, Control, and Management)

- How to use objectives

- Marketing Objectives

- Two key decisions

- Area of concentration

- Market standing

- The Innovation Objective (relating to the existing business)

- Resources Objectives

- Productivity Objectives

- The Social Responsibility Objectives

- Profit: A Need And Limitation

- Balancing Objectives

- From Objectives To Doing

- Summary

- 10 Making the Future Today

- We know only two things about the future

- Far-reaching implications

- Managers must accept the need to work systematically on making the future

- The Future That Has Already Happened

- The Power of an Idea

- Creativity (its not what you think it is)

- Summary

- 11 Strategic Planning: The Entrepreneurial Skill

- What Strategic Planning Is Not

- It is not a box of tricks, a bundle of techniques

- Strategic planning is not forecasting

- Strategic planning does not deal with future decisions, but the futurity of present decisions

- Strategic planning is not an attempt to eliminate risk

- What Strategic Planning Is

- Sloughing Off Yesterday

- What New Things Do We Have To Do — When?

- To sum up

- Everything Degenerates Into Work

- Summary

- See Mike Kami's Strategic Planning Manual

- Part III: Performance in Service Institutions

- 12 Managing Service Institutions in the Society of Organizations

- The Multi-Institutional Society

- Are Service Institutions Managed?

- But Are They Manageable?

- Managing Public-Service Instituiions For Performance

- They need to define "what our business is and what it should be."

- They must derive clear objectives and goals from their definition of function and mission

- They then must set priorities that enable them to …

- They must define measurements of performance

- They must use these measurements to feed back on their efforts

- They need an organized review of objectives and results, to weed out those objectives that no longer …

- To make service institutions perform it requires a system

- The applications of the essentials differ greatly for different service institutions. See Managing the Non-Profit Organization

- The Three Kinds Of Service Institutions

- Natural Monopoly

- Paid for Out of a Budget Allocation

- The Service Institution in Which Means Are as Important as Ends

- The Institutions' Specific Need

- The Natural Monopoly

- Socialist Competition in the Service Sector

- The Institutions of Governance

- Conclusion: What the service institutions need is not to be more businesslike

- Summary

- 13 What Successful and Performing Non profits Are Teaching Business

- A Commitment To Management

- Effective Use Of The Board

- To Offer Meaningful Achievement

- Training, Training, Training

- A Warning To Business: in my job there isn't much challenge, not enough achievement, not enough responsibility; and there is no mission, there is only expediency

- Managing the knowledge worker for productivity is the challenge ahead for American management.

- The nonprofits are showing us how to do that.

- It requires

- A clear mission

- Careful placement

- Continuous learning and teaching

- Management by objectives and self-control — see chapter 25 below

- High demands but corresponding responsibility and accountability for performance and results

- Summary

- 14 The Accountable School

- The New Performance Demands

- Learning To Learn

- The School In Society

- The Accountable School

- Summary

- 15 Rethinking "Reinventing Government"

- Restructuring

- Rethinking

- Abandoning

- An Exception For Crusades

- Government That's Effective

- Postscript

- Summary

- 16 Entrepreneurship in the Public-Service Institution

- Introduction

- Main reasons why the existing enterprise presents so much more of an obstacle to innovation

- The public-service institution is based on a "budget" rather than on being paid out of its results

- A service institution is dependent on a multitude of constituents

- Public-service institutions exist, after all, to "do good."

- These are serious obstacles to innovation

- There are enough exceptions to show that public-service institutions can innovate

- The entrepreneurial policies needed to make it capable of innovation

- The Need to Innovate

- Summary

- Part IV: Productive Work and Achieving Worker

- 17 Making Work Productive and the Worker Achieving

- Work And Worker In Rapid Change

- The Crisis Of The Manual Worker

- The Crisis Of The Union

- Unions And The Knowledge Workers

- Managing The Knowledge Worker: The New Challenge

- The Segmentation Of The Workforce

- The New Breed

- Summary

- 18 Managing the Work and Worker in Manual Work

- The Productivity Of The Manual Worker

- The Principles Of Manual-Work Productivity

- The Future Of Manual-Worker Productivity

- Summary

- 19 Managing the Work and Worker in Knowledge Work

- What We Know About Knowledge-Worker Productivity

- What Is The Task?

- The Knowledge Worker As Capital Asset

- The Technologists

- Knowledge Work As A System

- What to do about knowledge-worker productivity is thus largely known

- But How To Begin?

- The Governance Of The Corporation

- Summary

- Part V: Social Impacts and Social Responsibilities

- 20 Social Impacts and Social Responsibilities

- Responsibility For Impacts

- How To Deal With Impacts

- When Regulation Is Needed

- Social Problems As Business Opportunities

- The Limits Of Social Responsibility

- The Limits Of Authority

- The Ethics Of Responsibility

- Summary

- 21 The New Pluralism: How to Balance the Special Purpose of the Institution with the Common Good

- A Brief View Back

- Why We Need Pluralism

- Leadership Beyond The Walls

- Three Dimensions To This Integration

- Above All: Two Responsibilities

- Summary

- Part VI: The Manager's Work and Jobs

- 22 Why Managers?

- The Rise, Decline, And Rebirth Of Ford—A Controlled Experiment In Mismanagement

- GM—The Counter Test

- The Lesson Of The Ford Story

- Management As A "Change Of Phase"

- Summary

- 23 Design and Content of Managerial Jobs

- Guiding concepts

- Common Mistakes In Designing Managerial Jobs

- 1. The too-small job

- 2. The nonjob

- 3. Failing to balance managing and working

- 4. Poor job design

- 5. Titles as rewards

- 6. The widow-maker job

- Job Structure And Personality

- The Span Of Managerial Relationships

- Defining A Manager's Job

- Specific function

- Assignments

- Relationships

- Information needed for the job and by a manager's place in the information flow

- These four definitions, which together describe a manager's job, are the manager's own responsibility

- The Manager's Authority

- Managers, Their Superiors, Their Subordinates, And The Enterprise

- Summary

- 24 Developing Management and Managers

- Why Management Development?

- Why Manager Development?

- What Management Development Is Not

- Not taking courses

- Not promotion planning, replacement planning, or finding potential

- Not means to "make people over" by changing their personalities

- The Two Dimensions Of Development

- Summary

- 25 Management by Objectives and Self-Control (PDF)

- Four factors that tend to misdirect

- The Specialized Work Of Managers

- Misdirection By Hierarchy

- Misdirection can result from a difference in concern between various levels of management

- Misdirection By Compensation

- What Should The Objectives Be?

- Management By Drives

-

How Should Objectives Be Set and By Whom?

They have each of their subordinates write a manager's letter twice a year.

In this letter to the superior, managers first define the objectives of the superior's job and of their own job, as they see them.

They then set down the performance standards that they believe are being applied to them.

Next, they list the things they must do to attain these goals and the things within their own units they consider the major obstacles.

They list the things the superiors and the company do that help them and the things that hamper them.

Finally, they outline what they propose to do during the next year to reach their goals.

If their superiors accept this statement, the manager's letter becomes the charter under which the manager operates.

This device, like no other I have seen, brings out how easily the unconsidered and casual remarks of even the best boss can confuse and misdirect.

One large company has used the manager's letter for ten years.

Yet almost every letter still lists as objectives and standards things that baffle the superior to whom the letter is addressed.

And whenever she asks, "What is this?" she gets this sort of answer, "Don't you remember what you said last spring going down in the elevator with me?"

The manager's letter also brings out whatever inconsistencies there are in the demands made on a person by his or her superior and by the company.

Does the superior demand both speed and high quality when she can get only one or the other?

And what compromise is needed in the interest of the company?

Does the boss demand initiative and judgment of her people but also that they check back with her before they do anything?

Does the superior ask for ideas and suggestions but never uses them or discusses them?

Does the company expect of a small engineering force that it be available immediately whenever something goes wrong in the plant and yet bend all its efforts to the completion of new designs?

Does it expect managers to maintain high standards of performance but forbid them to remove poor performers?

Does it create the conditions under which people say, "I can get the work done as long as I can keep the boss from knowing what I am doing"?

As the manager's letter illustrates, managing managers requires special efforts not only to establish common direction, but to eliminate misdirection.

Mutual understanding can never be attained by "communications down," can never be created by talking.

It results only from "communications up."

It requires both the superior's willingness to listen and a tool especially designed to make lower managers heard.

- Self-Control Through Measurements

- Self-Control And Performance Standards

- A Philosophy Of Management

- Summary

- 26 From Middle Management to Information-Based Organizations

- Information Technology

- From Data To Information

- Converting Data Into Information Thus Requires Knowledge

- Content and Structure of the Information-Based Organization

- The British in India

- Requirements and Management Problems of the Information-Based Organization

- Requirements

- Special Management Problems

- Developing Rewards, Recognition, and Career Opportunities for Specialists

- Creating Unified Vision in an Organization of Specialists

- Devising the Management Structure for an Organization of Task Forces

- Ensuring the Supply, Preparation, and Testing of Top Management People

- Evolutions in the Concept and Structure of Organizations

- From Ownership to Management

- Command-and-Control Organization of Today

- The Organization of Knowledge Specialists

- Summary

- 27 The Spirit of Performance PDF

- The Danger Of Safe Mediocrity

- "Conscience" Decisions

- Focus On Opportunity

- "People" Decisions—The Control Of An Organization

- Integrity, The Touchstone

- Leadership And The Spirit Of Performance

- Leadership "Qualities"?

- The Undoing Of Leaders

- Earning Trust Is A Must

- Summary

- Part VII: Managerial Skills

- 28 The Elements of Effective Decision Making PDF

- Practices of Good Decision Makers

- The Elements Of Decision Making

- Determine Whether A Decision Is Necessary

- The Rules Used by Surgeons to Make Decisions

- The Recurring Crisis

- Classify The Problem

- Define The Problem

- Example

- The one way to make sure that the problem is correctly defined

- Decide On What Is Right

- Get Others To Buy The Decision

- 1. Japanese Decision-Making Process

- 2. Franklin Roosevelt's Decision Process

- Build Action Into The Decision

- Converting a Decision to Action

- Example: rationalize production

- Example: redesign instruments so they are easy to service

- Test The Decision Against Actual Results

- Summary: Seven Steps to Minimize Risks Inherent in Every Decision

- Building Continuous Learning Into Executive Decisions

- Summary

- 29 How to Make People Decisions

- Making People Decisions

- The Five Decision Steps

- Carefully think through the assignment

- Look at several qualified people

- Study the performance records of all three to five candidates to find what each does well

- Discuss the candidates with others who had worked with them

- Make sure the appointee understands the assignment

- Alfred P. Sloan, Jr., achieved a near perfect record in making people decisions

- The Five Ground Rules

- The manager must accept responsibility for any placement that fails

- The manager has the responsibility to remove people who do not perform

- Give nonperformers a second chance

- Try to make the right people decisions for every position

- Newcomers are best put into an established position where the expectations are known and help is available

- The High-Risk People Decisions

- What do I have to do now to be successful in this new assignment?

- The Widow-Maker Position

- Build Feedback Control Into People Decisions

- The Power Of Making People Decisions

- Summary

- 30 Managerial Communications

- 31 Controls, Control, and Management PDF

- The Characteristics Of Controls

- 1. Controls can be neither objective nor "neutral."

- 2. Controls need to focus on results

- 3. Controls are needed for measurable and nonmeasurable events

- Specification For Controls

- 1. Control is a principle of economy

- 2. Controls must be meaningful

- 3. Controls have to be appropriate to the character and nature of the phenomenon measured

- 4. Measurements have to be congruent with events measured

- 5. Controls have to be timely

- 6. Controls need to be simple

- 7. Finally, controls must he operational

- The Ultimate Control Of Organization

- Summary

- 32 The Manager and the Budget PDF

- The Budget Is A Managerial Tool

- Zero-Based Budgeting

- Types Of Cost

- Life-Cycle Budgeting

- Operating Budget And Opportunities Budget

- Budgeting Human Resources

- Budgeting And Control

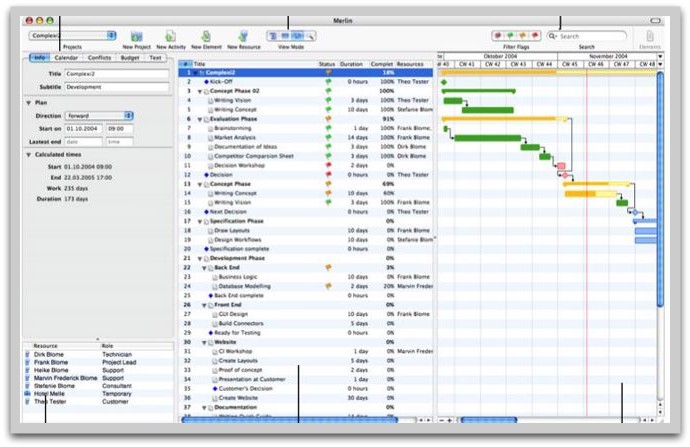

- The Gantt Chart And Network Diagrams

- Judging Performance By Using The Budget

- Summary

- 33 Information Tools and Concepts

- 1. Foundation Information That Enterprises Need

- From Cost Accounting to Result Control

- From Legal Fiction to Economic Reality

- 2. Information For Wealth Creation

- Productivity Information

- Competence Information

- Resource-Allocation Information

- Where the Results Are

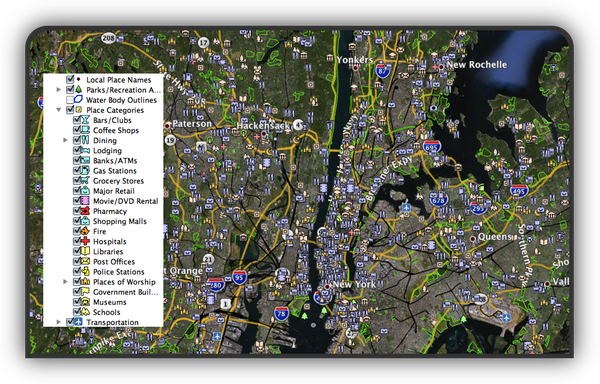

- 3. Information That Managers Need For Their Work

- No Surprises

- Going Outside

- Summary

- Part VIII: Innovation and Entrepreneurship

- 34 The Entrepreneurial Business

- Structures

- The new, has to be organized separately from the old and existing

- A special, high up locus is needed

- Burdens it cannot yet carry

- The Don'ts

- Don't mix managerial units and entrepreneurial ones

- Innovation had better not be "diversification."

- Acquisitions rarely work unless …

- Summary

- 35 The New Venture

- The Need For Market Focus

- Financial Foresight

- Building a Top Management Team

- "Where Can I Contribute?"

- The Need For Outside Advice

- Summary

- 36 Entrepreneurial Strategies

- Being "Fustest With The Mostest"

- Hitting Them Where They Ain't (Creative Imitation & Entrepreneurial Judo)

- Creative Imitation

- Entrepreneurial Judo

- The Five Bad Habits That Enable Newcomers to Use Entrepreneurial Judo

- 1. The first is what American slang calls NIH ("not invented here")

- 2. The second is the tendency to "cream" a market

- 3. Even more debilitating is the third bad habit: the belief in "quality."

- 4. The delusion of the "premium" price

- 5. They maximize rather than optimize

- Entrepreneurial judo aims first at securing a beachhead—and then the whole "island"

- Entrepreneurial judo requires some degree of genuine innovation

- Entrepreneurial judo "hits them where they ain't"

- Ecological Niches

- The Toll-Gate Strategy

- The Specialty-Skill Strategy

- The Speciality-Market Strategy

- Changing Values And Characteristics

- Creating Customer Utility

- Pricing

- Adapting to Customer Reality

- Delivering Value to the Customer

- Elementary Marketing

- Summary

- 37 Systematic Innovation Using Windows of Opportunity

- Seven Windows Of Opportunity

- 1. Unexpected successes ::: unexpected failures ::: unexpected events

- 2. Incongruities

- 3. Process needs

- 4. Changes in industry and market structures

- 5. Changes in demographics

- 6. Changes in meaning and perception

- 7. And finally: new knowledge

- A change in any one of these seven windows of opportunity raises the question …

- Innovation is not "flash of genius."

- Piloting

- Summary

- Part IX: Managerial Organization

- 38 Strategies and Structures

- Yesterday's Final Answers

- Traditional Assumptions And Current Needs

- Then vs. now

- Different types of businesses

- More complex, more diverse

- Global reach

- Different information flows

- Different types of workers

- More entrepreneurial

- What we now know

- Organization design and structure require thinking, analysis, and a systematic approach

- The first step is identifying and organizing the building blocks of organization

- Structure follows strategy

- The Three Kinds of Work: Top Management, Operating, Innovation

- What We Need To Unlearn

- The sham battle between task focus and person focus in job design and organization structure

- Hierarchical, or scalar, versus free-form organization

- One best principle alone is "right" and that it is also always "right."

- Instead of the "one right" principle

- The Building Blocks Of Organization

- The Key Activities

- In what area is excellence required to obtain the company's objectives?

- In what areas would nonperformance endanger the results, if not the survival, of the enterprise?

- What are the values that are truly important to us in this company?

- The key activities have to be identified, defined, organized, and centrally placed

- Business should always analyze its organization structure when its strategy changes

- The Contribution Analysis

- The "Conscience" Activities

- Making Service Staff Effective

- The Two Faces Of Information

- Housekeeping

- There is one overall rule

- The building blocks of organization

- Placing the structural units that make up the organization requires two additional pieces of work

- Decision Analysis

- What decisions are needed to obtain the performance objectives?

- Large company example: decisions had to "go looking for a home"

- Four basic characteristics determine the nature of any business decision

- Degree of futurity

- Impact a decision has on other functions

- Number of qualitative factors

- Decisions can be classified as periodically recurrent or rare

- Decision placement rules

- Relation Analysis

- Symptoms Of Poor Organization

- There is no perfect organization

- At its best, an organization structure doesn't cause trouble

- Mistakes and symptoms

- An increase in the number of management levels

- Recurring organizational problems

- An organization structure that puts the attention of key people on the wrong …

- Several common symptoms of poor organization that, usually, require no further diagnosis

- Too many meetings attended by too many people

- People are constantly concerned about feelings and about what other people …

- Overstaffed organizations create work rather than performance

- Relying on "coordinators," "assistants," and …

- "Organizitis" As A Chronic Affliction

- Summary

- Five Design Principles

- 39 Work- and Task-Focused Design

- Formal Specifications (for Organization Structure)

- 1. Clarity

- 2. Economy

- 3. The direction of vision

- 4. Understanding one's own task and the common task

- 5. Decision making

- 6. Stability and adaptability

- 7. Perpetuation and self-renewal

- Meeting The Specifications

- Three Ways Of Organizing Work

- Stages in the process

- The work moves to where the skill or tool required for each of the steps is located

- A team of workers with different skills and different tools moves to the work

- Functional organization organizes work both by stages and by skills

- In the "team structure," however, work and task are, so to speak, fixed

- Both functional and team structures are old designs

- Work and task have to be structured and organized

- The Functional Structure (and the specifications)

- Its Limited Scope (to operating work)

- Where Functionalism Works

- The Team

- The Requirements of Team Design

- The Strengths and Limitations of the Team Principles

- The Scope of Team Organization

- Team Design And The Knowledge Organization

- Summary

- 40 Three Kinds of Teams

- The first kind of team is the baseball team.

- The second kind of team is the football team

- The third kind of team is the tennis doubles team

- Observations on the baseball-style team

- Observations on the football-style team

- Observations on the doubles team

- Observations on theses teams

- Summary

- 41 Result- and Relation-Focused Design

- Federal Decentralization

- The Strength of Federal Decentralization

- The Requirements of Federal Decentralization

- Size Requirements

- How Small Is Too Small?

- What Is a "Business"?

- Simulated Decentralization

- The Problems of Simulated Decentralization

- Rules for Using Simulated Decentralization

- The Systems Structure

- The Difficulties and Problems of the Systems Structure

- Summary

- 42 Alliances

- Why Do Organizations Enter into Alliances?

- The Different Types of Alliances

- Common Problems Facing All Alliances and Their Resolution

- Managing Alliances As Marketing Partnerships

- Summary

- 43 The CEO in the New Millennium — here

- The Work Of The CEO: The Link Between The Inside And Outside

- The Tasks Of The CEO

- To define the meaningful outside of the organization

- To work on getting information from the 'outside' into usable form

- To decide what results are meaningful for the institution

- To decide the priorities

- To place people into key positions

- To organize top management

- The CEO: An American Invention And Export

- Summary

- 44 The Impact of Pension Funds on Corporate Governance (core work toward)

- Intro

- The rise of pension funds as dominant owners and lenders represents one of the most startling power shifts in economic history

- Demographics guarantee that these assets will continue to grow aggressively

- Two questions, in particular, demand attention:

- For what should America’s new owners, the pension funds, hold corporate management accountable?

- And what is the appropriate institutional structure through which to exercise accountability?

- Can't Sell

- “If one can’t sell, one must care.”

- Thus pension funds, as America’s new owners, will increasingly have to make sure that a company has the management it needs.

- It means that management must be accountable for performance and results, rather than for good intentions, however beautifully quantified.

- It means that accountability must involve financial accountability, even though everyone knows that performance and results go way beyond the financial “bottom line.”

- Surely, most people will say, we know what performance and results mean for business enterprise.

- We should of course, because clearly defining these terms is a prerequisite both for effective management and for successful and profitable ownership.

- Management For The Stakeholders

- What makes takeovers and buyouts inevitable (or at least creates the opportunity for them) is the mediocre performance of management, the management without clear definitions of performance and results and with no clear accountability to somebody.

- The raiders and buyout firms thus perform a needed function.

- As an old proverb has it, “If there are no grave diggers, one needs vultures.”

- But takeovers and buyouts are very radical surgery.

- And even if radical surgery is not life-threatening, it inflicts profound shock.

- For most people, “maximizing shareholder value” means a higher share price within six months or a year—certainly not much longer.

- Such short-term capital gains are the wrong objective for both the enterprise and its dominant shareholders.

- As a theory of corporate performance, then, “maximizing shareholder value” has little staying power.

- The interest of a large pension fund is in the value of a holding at the time at which a beneficiary turns from being an employee, who pays into the fund, to being a pensioner, who gets paid by the fund.

- Concretely, this means that the time over which a fund invests—the time until its future beneficiaries will retire—is on average thirty years rather than three months or six months.

- This is the appropriate return horizon for these owners.

- We no longer need to theorize about how to define performance and results in the large enterprise.

- … Rather, they maximize the wealth-producing capacity of the enterprise.

- It is this objective that integrates short-term and long-term results and that ties the operational dimensions of business performance—market standing, innovation, productivity, and people and their development—to financial needs and financial results.

- It is also this objective on which all constituencies depend for the satisfaction of their expectations and objectives, whether shareholders, customers, or employees.

- To define performance and results as maximizing the wealth-producing capacity of the enterprise may be criticized as vague.

- To be sure, one doesn’t get the answers by filling out forms.

- Decisions need to be made, and economic decisions that commit scarce resources to an uncertain future are always risky and controversial.

- Financial objectives are needed to tie all this together.

- Indeed, financial accountability is the key to the performance of management and enterprise.

- Without financial accountability, there is no accountability at all.

- And without financial accountability, there will also be no results in any other area.

- What we have is not the “final answer.”

- Still, it is no longer theory but proven practice.

- Institutional Structure For Accountability

- For while the business audit need not be conducted every year (every three years may be enough in most cases), it needs to be based on predetermined standards and go through a systematic evaluation of business performance, starting with mission and strategy, through marketing, innovation, productivity, people development, community relations, all the way to profitability — see chapter 9

- Still, the question remains, Who is going to use this tool?

- In the American context, there is only one possible answer: a revitalized board of directors.

- An Effective Board

- Spelling out its work

- Setting specific objectives for its performance and contribution

- Regularly appraising the board’s performance against these objectives.

- Summary

- Part X: New Demands on the Individual

- 45 Managing Oneself

- Now even people of modest endowments have to manage themselves

- Who am I?

- 1. What Are My Strengths?

- Am I A Reader Or A Listener?

- How Do I Learn?

- To manage oneself, one has to ask additional questions

- What Are My Values?

- What to Do in a Value Conflict

- 2. Where Do I Belong?

- 3. What Is My Contribution?

- 4. Relationship Responsibility

- Accepting that other people are as much individuals as one is oneself

- Take responsibility for communications

- Summary

- 46 Managing the Boss

- Most Of Us Have More Than One Boss

- The Boss Is Key To Effectiveness

- Neglect Of Managing The Boss

- Who Is The Boss?

- Managing The Boss

- 1. Making a Boss List

- 2. Asking for Input

- 3. Enabling Bosses to Perform

- 4. Playing to the Bosses' Strengths

- 5. Keeping Bosses Informed

- 6. Protecting Bosses from Surprises

- 7. Never Underrating Bosses

- Summary

- 47 Revitalizing Oneself-Seven Personal Experiences

- Experience One: Goal And Vision Taught By Verdi

- Experience Two: "The Gods Can See Them"—Taught By Phidias

- Experience Three: Continuous Learning Decision As A Journalist

- Experience Four: Reviewing—Taught By the Editor In Chief

- Experience Five: What Is Necessary In A New Position—Taught By The Senior Partner

- Experience Six: Writing Down—Taught By The Jesuits And The Calvinists

- Experience Seven: What To Be Remembered For—Taught By Schumpeter

- The Same Thing Can Be Learned

- One's Own Responsibility

- Summary

- 48 The Educated Person

- At The Core Of The Knowledge Society

- The knowledge society requires a unifying force

- A universally educated person

- The Glass Bead Game

- Their liberal education does not enable them to understand or master reality

- Areas of education

- The wisdom, beauty, knowledge, that are the heritage of mankind

- Needs to be able to bring his or her knowledge to bear on the present and future

- Appreciate other cultures and traditions

- Far less exclusively "bookish"

- Trained in perception fully as much as analysis

- The Western tradition

- Prepared for life in a global and tribalized world

- Knowledge Society And Society Of Organizations

- The educated person will have to be prepared to live and work simultaneously in two cultures

- Technes And Educated Person

- The ability to understand the various knowledges

- To Make Knowledges A Path To Knowledge

- Major new insights in every one of the specialized knowledges arise out of another

- Specialists have to take responsibility for making both themselves and their specialty understood

- All knowledges are equally valuable

- The greatest change will be the change in knowledge

- Summary

- Conclusion: The Manager of Tomorrow

- In the politics, society, and economy that lie half a century ahead there will be great changes

- Important things with respect to the manager of tomorrow

- Yet the three tasks of the manager will be the same

- The performance of the institution for which they work

- Making work productive and the worker achieving

- Managing social impact and social responsibilities

- Will be expected to tackle these tasks with more knowledge, more thought, more planning …

- Learn how to manage in situations where they do not have command authority

- Managers will have to make productive people who work for them but are not employees

- Information is replacing authority

- Significant expansion in the application of managerial tasks

- Major thrust toward systematic management in the public-service institution

- Major priorities with respect to each of the major task areas

- Organize for systematic abandonment

- Make the management of human resources within our organizations conform to social reality

- The "working class" has changed dramatically in all developed countries

- The traditional line between "worker" and "owner" is fast disappearing

- The need to manage one's own career

- Managing social impact and social responsibility

- The difficult and risky "trade-offs" between conflicting needs and conflicting rights

- Think ahead with respect to the social impacts of the institutions

- This is a leadership responsibility

- These are new challenges for management and new demands on it

- The Individual Manager

- The manager of tomorrow will increasingly have more than one career

- Action areas

- Continued learning by managers

- Taking responsibility for self-development as a person and as a manager

- Thorough knowledge of a manager's work, managerial skills, and managerial tools

- Most important thing one can predict, with respect to the manager of tomorrow, is that there will be a manager of tomorrow, one defined by expected contribution

- In all likelihood, there will be more managers tomorrow than there are today, and they will matter more

- Society will continue to be a society of organizations and a knowledge society

- Every reason to expect society to demand more performance from all its institutions

- Author's Note

- Bibliography

- American Books About Peter F. Drucker

- 1. Origins, Foundations, and Tasks of Management

- 2. Management as a Process and a Discipline

- 3. Management in Japan

- 4. Managing for Performance

- 5. Work and Worker

- 6. Social Impacts and Social Responsibilities

- 7. The Manager's Work and Job

- 8. Managerial Skills and Managerial Tools

- 9. Organization Design and Structure

- 10. The Top-Management Job

- 11. Strategies and Structure

- 12. The Multinational Corporation

- 13. The Innovative Organization

- 14. The Manager of Tomorrow

- Drucker's Annotated Bibliography

- The End of Economic Man

- The Future of Industrial Man

- Concept Of The Corporation

- The New Society

- The Practice of Management

- America's Next Twenty Years

- Landmarks of Tomorrow

- Managing for Results

- The Effective Executive

- The Age of Discontinuity

- Men, Ideas, and Politics

- Technology, Management, and Society

- Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

- The Pension Fund Revolution

- Adventures of a Bystander

- Managing in Turbulent Times

- Toward the Next Economics

- The Changing World of the Executive

- Innovation and Entrepreneurship

- The Frontiers of Management

- The New Realities

- Managing the Non-Profit Organization

- Managing for the Future

- The Ecological Vision

- Post-Capitalist Society

- Managing in a Time of Great Change

- Drucker on Asia

- Peter Drucker on the Profession of Management

- Management Challenges for the 21st Century

- Managing in the Next Society

- The Daily Drucker (with Joseph A. Maciariello)

- The Effective Executive in Action (with Joseph A. MaciarieUo)

- Anthologies

- The Essential Drucker

- A Functioning Society

- Novels

- The Last of All Possible Worlds

- The Temptation to Do Good

- About Peter F. Drucker

Administration And Entrepreneurship

Managers always have to administer, to manage and improve, what already exists and is already known.

But there is another dimension to managerial performance.

Managers also have to be entrepreneurs.

They have to redirect resources from areas of low or diminishing results to areas of high or increasing results.

They have to slough off yesterday and to make obsolete what already exists and is already known.

They have to create tomorrow.

In the ongoing business markets, technologies, products, and services exist.

Facilities and equipment are in place.

Capital has been invested and has to be serviced.

People are employed and are in specific jobs, and so on.

The administrative job of the manager is to optimize the yield from these resources.

This [we are usually told, especially by economists,] means efficiency, that is, doing better what is already being done.

It means focus on costs.

But the optimizing approach should focus on effectiveness.

It focuses on opportunities to produce revenue, to create markets, and to change the economic characteristics of existing products and markets.

It asks not, How do we do this or that better?

It asks, Which of the products really produce extraordinary economic results or are capable of producing them?

Which of the markets and/or end uses are capable of producing extraordinary results?

It then asks, To what results should, therefore, the resources and efforts of the business be allocated so as to produce extraordinary results rather than the “ordinary” ones, which is all efficiency can possibly produce?

Of course efficiency is important.

Even the healthiest business, the business with the greatest effectiveness, can die of poor efficiency.

But even the most efficient business cannot survive, let alone succeed, if it is efficient in doing the wrong things, that is, if it lacks effectiveness.

No amount of efficiency would have enabled the manufacturer of buggy whips to survive.

Effectiveness is the foundation of success—efficiency is a minimum condition for survival after success has been achieved.

Efficiency is concerned with doing things right.

Effectiveness is doing the right things.

Efficiency concerns itself with the input of effort into all areas of activity.

Effectiveness, however, starts out with the realization that in business, as in any other social organism, 10 or 15 percent of the phenomena—such as products, orders, customers, markets, or people—produce 80 to 90 percent of the results.

The other 85 to 90 percent of the phenomena, no matter how efficiently taken care of produce nothing but costs.

The first administrative job of the manager is, therefore, to make effective the very small core of worthwhile activities that is capable of being effective.

At the same time, he or she neutralizes (or abandons) the very large number of ordinary transactions—products or staff activities, research work or sales efforts—that, no matter how well done, will not yield extraordinarily high results.

The second administrative task is to bring the business all the time a little closer to the full realization of its potential.

Even the most successful business works at a low performance as measured against its potential—the economic results that could be obtained were efforts and resources marshaled to produce the maximum yield they are inherently capable of.

This task is not innovation; it actually takes the business as it is today and asks, What is its theoretical optimum?

What prevents us from attaining it?

Where (in other words) are the limiting and restraining factors that hold back the business and deprive it of the full return on its resources and efforts?

At the same time, inherent in the managerial task is entrepreneurship:

making the business of tomorrow.

Inherent in this task is innovation.

Making the business of tomorrow starts out with the conviction that the business of tomorrow will be and must be different.

But it also starts out—of necessity—with the business of today.

Making the business of tomorrow cannot be a flash of genius.

It requires systematic analysis and hard, rigorous work today—and that means by people in today’s business and operating within it.

Success cannot, one might say, be continued forever.

Businesses are, after all, human creations, which have no true permanence.

Even the oldest businesses are creations of recent centuries.

But a business enterprise must continue beyond the lifetime of the individual or of the generation to be capable of producing its contributions to economy and to society.

The perpetuation of a business is a central entrepreneurial task—and ability to do so may well be the most definitive test of a management.

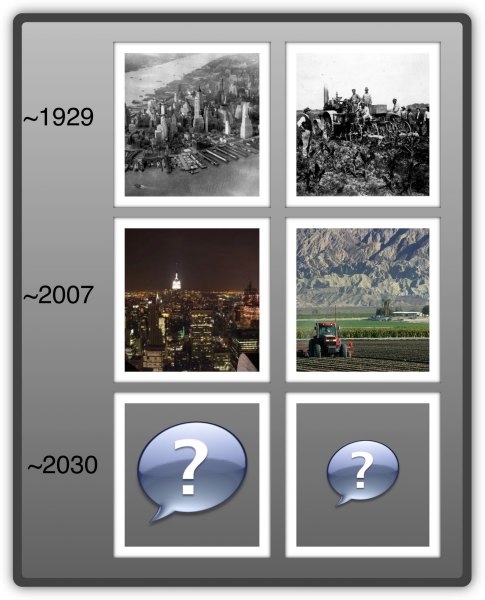

The New Workforce

A century ago, the overwhelming majority of people in developed countries worked with their hands: on farms, in domestic service, in small craft shops, and (at that time still a small minority) in factories.

Fifty years later, the proportion of manual workers in the American labor force had dropped to around half, but factory workers had become the largest single section of the workforce, making up 35 percent of the total.

Now, another fifty years later, fewer than a quarter of American workers make their living from manual jobs.

Factory workers still account for the majority of the manual workers, but their share of the total workforce is down to around 15 percent—more or less back to what it had been one hundred years earlier.

Of all the big developed countries, America now has the smallest proportion of factory workers in its labor force.

Britain is not far behind.

In Japan and Germany, their share is still around a quarter, but it is shrinking steadily.

To some extent this is a matter of definition.

Data-processing employees of a manufacturing firm, such as the Ford Motor Company, are counted as employed in manufacturing, but when Ford outsources its data processing, the same people doing exactly the same work are instantly redefined as service workers.

However, too much should not be made of this.

Many studies in manufacturing businesses have shown that the decline in the number of people who actually work in the plant is roughly the same as the shrinkage reported in the national figures.

Before the First World War there was not even a word for people who made their living other than by manual work.

The term service worker was coined around 1920, but it has turned out to be rather misleading.

These days, fewer than half of all nonmanual workers are actually service workers.

The only fast-growing group in the workforce, in America and in every other developed country, is “knowledge workers”—people whose jobs require formal and advanced schooling.

They now account for a full third of the American workforce, outnumbering factory workers by two to one.

In another twenty years or so, they are likely to make up close to two-fifths of the workforce of all rich countries.

The terms knowledge industries, knowledge work, and knowledge worker are only forty years old.

They were coined around 1960, simultaneously but independently; the first by a Princeton economist, Fritz Machlup, the second and third by this writer.

Now everyone uses them, but as yet hardly anyone understands their implications for human values and human behavior, for managing people and making them productive, for economics and for politics.

What is already clear, however, is that the emerging knowledge society and knowledge economy will be radically different from the society and economy of the late twentieth century, in the following ways.

First, the knowledge workers, collectively, are the new capitalists.

Knowledge has become the key resource, and the only scarce one.

This means that knowledge workers collectively own the means of production.

But as a group, they are also capitalists in the old sense: Through their stakes in pension funds and mutual funds, they have become majority shareholders and owners of many large businesses in the knowledge society.

Effective knowledge is specialized.

That means knowledge workers need access to an organization—a collective that brings together an array of knowledge workers and applies their specialisms to a common end product.

The most gifted mathematics teacher in a secondary school is effective only as a member of the faculty.

The most brilliant consultant on product development is effective only if there is an organized and competent business to convert her advice into action.

The greatest software designer needs a hardware producer.

But in turn the high school needs the mathematics teacher, the business needs the expert on product development, and the PC manufacturer needs the software programmer.

Knowledge workers therefore see themselves as equal to those who retain their services, as “professionals” rather than as “employees.”

The knowledge society is a society of seniors and juniors rather than of bosses and subordinates.

Creativity

Opportunities ::: Serious creativity

To make the future happen one need not, in other words, have a creative imagination.

It requires work rather than genius—and therefore is accessible in some measure to everybody.

The man of creative imagination will have more imaginative ideas, to be sure.

But that the more imaginative idea will actually be more successful is by no means certain.

Pedestrian ideas have at times been successful;

Bata’s idea of applying American methods to making shoes was not very original in the Europe of 1920, with its tremendous interest in Ford and his assembly line.

What mattered was his courage rather than his genius.

To make the future happen one has to be willing to do something new.

One has to be willing to ask,

“What do we really want to see happen that is quite different from today?”

One has to be willing to say,

“This is the right thing to happen as the future of the business.

We will work on making it happen.”

Lack of “creativity,” which looms so large in present discussions of innovation, is not the real problem.

There are more ideas in any organization, including businesses, than can possibly be put to use.

What is lacking, as a rule, is the willingness to look beyond products to ideas.

[See Sur/petition]

Products and processes are only the vehicle through which an idea becomes effective.

See piloting and strategies

Dense reading and Dense listening and Thinking broad and Thinking detailed

And, as the illustrations should have shown, the specific future products and processes can usually not even be imagined.

When DuPont started the work on polymer chemistry out of which nylon eventually evolved, it did not know that man-made fibers would be the end product.

DuPont acted on the assumption that any gain in man’s ability to manipulate the structure of large, organic molecules—at that time in its infancy—would lead to commercially important results of some kind.

Only after six or seven years of research work did man-made fibers first appear as a possible major result area.

Moreover, the manager often lacks the courage to commit resources to such an idea.

The resources that should be invested in making the future happen should be small, but they must be of the best.

Otherwise nothing happens.

However, the greatest lack of the manager is a touchstone of validity and practicality.

An idea has to meet rigorous tests if it is to be capable of making the future of a business.

It has to have operational validity.

Can we take action on this idea?

Or can we only talk about it?

Can we really do something right away to bring about the kind of future we want to make happen?

To be able to spend money on research is not enough.

It must be research directed toward the realization of the idea.

The knowledge sought may be general, as was that of DuPont’s project.

But it must at least be reasonably clear that if available, it would be applicable knowledge.

The idea must also have economic validity.

If it could be put to work right away in practice, it should be able to produce economic results.

We may not be able to do what we would like to for a long time, perhaps never.

But if we could do it now, the resulting products, processes, or services would find a customer, a market, an end-use; should be capable of being sold profitably; should satisfy a want and a need.

The idea itself might aim at social reform.

But unless an organization can be built on it, it is not a valid entrepreneurial idea.

The test of the idea is not the votes it gets or the acclaim of the philosophers.

It is economic performance and economic results.

Even if the rationale of the business is social reform rather than business success, the touchstone must be the ability to perform and to survive as a business.

Finally, the idea must meet the test of personal commitment.

Do we really believe in the idea?

Do we really want to be that kind of people, do that kind of work, run that kind of business?

To make the future demands courage.

It demands work.

But it also demands faith.

To commit ourselves to the expedient is simply not practical.

It will not suffice for the tests ahead.

For no such idea is foolproof—nor should it be.

The one idea regarding the future that must inevitably fail is the apparently “sure thing,” the “riskless idea,” the one “that cannot fail.”

The idea on which tomorrow’s business is to be built must be uncertain; no one can really say as yet what it will look like if and when it becomes reality.

It must be risky:

it has a probability of success but also of failure.

If it is not both uncertain and risky, it is simply not a practical idea for the future.

For the future itself is both uncertain and risky.

Unless there is personal commitment to the values of the idea and faith in them, the necessary efforts will therefore not be sustained.

The manager should not become an enthusiast, let alone a fanatic.

She should realize that things do not happen just because she wants them to happen—not even if she works very hard at making them happen.

Like any other effort, the work on making the future happen should be reviewed periodically to see whether continuation can still be justified both by the results of the work to date and by the prospects ahead.

Ideas regarding the future can become investments in managerial ego too, and need to be carefully tested for their capacity to perform and to give results.

But the people who work on making the future also need to be able to say with conviction, “This is what we really want our business to be.”

It is perhaps not absolutely necessary for every organization to search for the idea that will make the future.

A good many organizations and their managements do not even make their present organizations effective—and yet the organizations somehow survive for a while.

The big business, in particular, seems to be able to coast a long time on the courage, work, and vision of earlier managers.

But tomorrow always arrives.

It is always different.

And then even the mightiest company is in trouble if it has not worked on the future.

It will have lost distinction and leadership—all that will remain is big-company overhead.

It will neither control nor understand what is happening.

Not having dared to take the risk of making the new happen, it perforce took the much greater risk of being surprised by what did happen.

And this is a risk that even the largest and richest organization cannot afford and that even the smallest one need not run.

To be more than a slothful steward of the talents in one’s keeping, the manager has to accept responsibility for making the future happen.

It is the willingness to tackle this purposefully that distinguishes the great organization from the merely competent one, and the organization builder from the manager-suite custodian.

A scorecard for managers A scorecard for managers

Company performance: five telltale tests Company performance: five telltale tests

Without an effective mission statement, there will be no performance Without an effective mission statement, there will be no performance

Continuity and change Continuity and change

Look Look

Management Challenges for the 21st Century Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Making the future Making the future

Managing in the Next Society Managing in the Next Society

Piloting from Management, Revised Edition

“Enterprises of all kinds increasingly use all kinds of market research and customer research to limit, if not eliminate, the risks of change.

But one cannot market research the truly new.

Also nothing new is right the first time.

Invariably, problems crop up that nobody even thought of.

Invariably, problems that loomed very large to the originator turn out to be trivial or not to exist at all.

Above all, the way to do the job invariably turns out to be different from what was originally designed.

It is almost a “law of nature” that anything that is truly new, whether product or service or technology, finds its major market and its major application not where the innovator and entrepreneur expected, and not to be the use for which the innovator or entrepreneur has designed it.

And that, no market or customer research can possibly discover.

The best example is an early one:

The improved steam engine that James Watt (1736-1819) designed and patented in 1776 is the event that, for most people, signifies the advent of the Industrial Revolution.

Actually, Watt until his death saw only one use for the steam engine: to pump water out of coal mines.

That was the use for which he had designed it.

And he sold it only to coal mines.

It was his partner, Matthew Boulton (1728-1809), who was the real father of the Industrial Revolution.

Boulton saw that the improved steam engine could be used in what was then England’s premier industry, textiles, and especially in the spinning and weaving of cotton.

Within ten or fifteen years after Boulton had sold his first steam engine to a cotton mill, the price of cotton textiles had fallen by 70 percent.

And this created both the first mass market and the first factory—and together modern capitalism and the modern economy altogether.

Neither studies nor market research not computer modeling are a substitute for the test of reality.

Everything improved or new needs, therefore, first to be tested on a small scale, that is, it needs to be piloted.

The way to do this is to find somebody within the enterprise who really wants the new.

As said before, everything new gets into trouble.

And then it needs a champion.

It needs somebody who says, “I am going to make this succeed,” and who then goes to work on it.

And this person needs to be somebody whom the organization respects.

This need not even be somebody within the organization.

A good way to pilot a new product or new service is often to find a customer who really wants the new, and who is willing to work with the producer on making the new product or the new service truly successful.

If the pilot test is successful—if it finds the problems nobody anticipated but also finds the opportunities that nobody anticipated, whether in terms of design, of market, of service—the risk of change is usually quite small.

And it is usually also quite clear where to introduce the change and how to introduce it, that is, what entrepreneurial strategy to employ.”

43 The CEO in the New Millennium (PDF)

The Work Of The CEO: The Link Between The Inside And Outside

CEOs have ultimate responsibility for the work of everybody else in their institution.

But they also have work of their own—and the study of management has so far paid little attention to it.

It is the same work regardless of whether the organization is a business enterprise, a nonprofit, a church, a school or university, or a government agency, or whether it is large or small, worldwide or purely local.

And it is work only CEOs can do, but also work that CEOs must do.

---XXX---

In any organization, regardless of its mission, the CEO is the link between the inside, that is, the organization, and the outside, that is, society, the economy, technology, markets, customers, the media, public opinion.

Inside, there are only costs.

Results are only on the outside.

Indeed, the modern organization (beginning with the Jesuit Order in 1536) was expressly created to have results on the outside, that is, to make a difference in its society or its economy.

The Tasks Of The CEO

To define the meaningful outside of the organization.

To define the meaningful outside of the organization is the CEO’s first task.

The definition is anything but easy, let alone obvious.

For a particular bank, for instance, is the meaningful outside the local market for commercial loans?

Is it the national market for mutual funds?

Or is it major industrial companies and their short-term credit needs?

All three of these “outsides” deal with money and credit.

And one cannot tell from the bank’s published accounts, for example, its balance sheet, on which of these “outsides” it concentrates.

Each of them is a different business and requires a different organization, different people, different competencies, and different definitions of results.

Even the very biggest bank is unlikely to be a leader in all of these “outsides.”

And which of these to concentrate on is a highly risky decision and one very hard to change or reverse.

Only the CEO can make it.

But also the CEO must make it.

It is the first task of the CEO.

To work on getting information from the ‘outside’ into usable form.

The second specific task of the CEO is to think through what information regarding the outside is meaningful and needed for the organization and then to work on getting it into usable form.

Organized information has grown tremendously in the last hundred years.

But the growth has been mainly in “inside” information, for example, accounting.

The computer has further accentuated this inside focus.

As regards the outside, there has been an enormous growth in data—beginning with Herbert Hoover in the 1920s (to whose work as secretary of commerce we largely owe the data on GNP, on productivity, and on standard of living).

But few CEOs, whether in business, in nonprofits, or in government agencies, have yet organized these data into systematic information for their own work (on the methodology for doing this, see chapter 33).

---XXX---

To give one example, every major maker of branded consumer goods knows that few things are as important as the values and the behavior of that great majority of consumers who are not buyers of the company’s products, and especially information on major changes in the noncustomers’ values and habits.

The data are largely available.

But so far few consumer-goods manufacturers have converted them into organized information on which to base their decisions (one well-publicized exception is the Shell Petroleum group of companies).

Again it is primarily the CEO who needs this information and whose work it is to organize getting it.

---XXX---

Thinking through what is meaningful information on the outside is also a high-risk decision

That U.S. business executives, for instance in the 1950s and 1960s, decided (in many cases quite deliberately) that what was going on in Japan was not particularly meaningful information for them and their companies explains in large part why the Japanese export push caught them so unawares and unprepared.

---XXX---

It is information about the outside that needs the most work.

For far too many institutions-and not only businesses-define “outside” in large part as their direct competitors.

Toy makers tend to define the “outside” as their toy-maker competitors; a hospital, as the other two competing hospitals in the same suburb; and so on.

But the most meaningful competitors for the toy maker are not other toy makers but other claimants on potential customers’ disposable dollars.

The most meaningful information about the toy maker’s outside is therefore what value the toy presents to the potential buyer.

(Customer research, in other words, may be more important than market research—but also far more difficult.)

To decide what results are meaningful for the institution.

The definition of the institution’s meaningful outside and of the information the institution needs makes it possible to answer the key questions, “What is our business?

What should it be?

What should it not be?”

The answers to these questions establish the boundaries within which an institution operates.

And they are the foundation for the specific work of the CEO.

Particularly, they enable the CEO to decide what results are meaningful for the institution.

---XXX---

Defining results is important, critical, and risky above all for institutions that lack the discipline of the “bottom line,” that is, for nonbusinesses.