It is useful to have an overview of some of the most basic processes in thinking before we look in detail at each of the five stages.

These processes come in at every stage so it is useful to have a preview of them here.

The basic processes that are going to be considered here are:

Broad/specific

Projection

Attention directing

Recognition

Movement

I am aware that these matters can be looked at in many ways.

Each of these broad areas could be subdivided and each subdivision could claim to be a basic process in its own right.

For the sake of simplicity I have made the above choice.

Broad/Specific, General/Detail

Imagine a short-sighted person seeing a cat for the first time.

There is a blurry image and the person sees ‘a sort of animal’.

As the cat gets nearer the details gradually emerge and now the person gets a true picture of a cat.

Imagine two hawks.

One of them has excellent eyesight but the other is short-sighted.

Both of them live on a diet of frogs, mice and lizards.

From a great height the hawk with excellent eyesight can see and recognize a frog.

It dives and eats the frog.

Because this hawk has such excellent eyesight it can live on a diet of frogs and soon forgets about mice and lizards.

The hawk with poor eyesight cannot do this.

This hawk has to create a general concept of ‘small things that move’.

Whenever it sees a small thing that moves the hawk dives.

Sometimes it gets a frog, sometimes a mouse, sometimes a lizard and occasionally a child’s toy.

Most people would immediately regard the hawk with superior eyesight as a superior hawk.

In some ways they would be wrong.

If frogs died out the first hawk would also die but the second hawk would carry on with very little disturbance.

This is because the poor-eyesight hawk has flexibility.

This flexibility arise’ from the creation of the general, broad and blurry concept of ‘small things that move’.

Thinking broad and Thinking detailed

Dense reading and Dense Listening

Seeing broadly

Some electronic students were given a simple circuit to complete.

Ninety-seven per cent of them complained that they did not have enough wire to complete the circuit …

Only 3 per cent completed the circuit.

The 97 per cent wanted ‘wire’ and since there was no wire they could not complete the task.

The 3 per cent had a broad, general, blurry concept of ‘a connector’.

Since wire was not available they looked around for another type of connector.

They used the screwdriver itself to complete the circuit.

Most of the advantages of the human brain as a thinking machine arise from its defects as an information machine.

Because the brain does not immediately form exact, detailed images we have a stock of broad, general and blurry images which become concepts.

These broad, general and blurry images are immensely useful in thinking.

Consider the difference between the following two requests:

• ‘I want some glue to stick these two pieces of wood together.’

• ‘I want some way of sticking these two pieces of wood together.’

The first is very specific.

If glue is not available then the task cannot be done.

It may also be that glue is not the best way of sticking the pieces together on this occasion.

The second request includes many alternative ways of sticking the two pieces of wood together: glue, nails, screws, clamps, rope, joints, etc.

This both allows for flexibility if glue is not available and also allows consideration of the other options.

Good thinkers have this great ability to keep moving from the detail back to the general, from the specific to the broad and then back again.

When we look for a solution to a problem we often have to consider it in very broad terms first.

‘We need some way of fixing this to a wall.’

Then we proceed to narrow down the broad to something specific.

In the end we can only ‘do’ specific things.

But the broad, blurry concepts allow us to search more widely, to be more flexible and to evaluate options.

This ability to move from the detail to the general is sometimes called abstraction — a term that is more confusing than helpful.

As we go through the five stages of thinking you will see the frequent changes from the broad to the specific and back again.

In thinking we are always urged to be precise.

This is one area where you are encouraged to be broad and blurry.

Of course, you have to be ‘blurry’ in roughly the right direction.

If you are looking for ‘some way to fix something to the wall’ it is not much use looking for ‘some way to fry an egg’.

Projection

Imagine that you have a video player in your mind.

You press the button and you see played out in your mind a particular scene.

• Projection means running something forward in your mind.

• Projection means imaginings

• Projection means visualizing.

We can see things in the world around us.

Projection means looking inwards into our minds and seeing things there.

A car is painted white on one side and black on the other side.

Imagine what would happen if that car was involved in an accident.

In our mind’s eye we can see witnesses in court contradicting each other: one declaring the car to be black and another declaring it to be white.

Most humour involves projection.

We need to imagine the scene.

Projection is a very basic part of thinking because we cannot check out everything in the real world.

So we have to ‘see what would happen’ and to check things out in our minds.

We may be wrong and we may not get a very clear picture but at least we can get some indication.

‘What would happen if all public transport were to be free?’

Someone will imagine the benefits to poorer people.

Someone will imagine the overcrowding.

Someone will imagine the benefits to in-town shops.

Someone may even imagine the cost being put on everyone’s taxes.

‘What would happen if a block of ice floating in a glass of water melted?

Would the level of water in the glass go up, go down or remain the same?’

You would need some understanding of physics to answer that question.

Our imagination is limited by our knowledge and experience but we have to use it as best we can.

‘What would it look like if we removed that circle and replaced it with a triangle?’

A designer always has to project and visualize what would happen if something were to be done.

The famous thought experiments used by Einstein depend on projection.

In a thought experiment you run the experiment in your mind and see what happens.

You may reach a point when you have to say to yourself that you do not know what would happen.

This now becomes a point for further thinking or for carrying out an experiment.

In some cases thinking is indeed carried out with figures and mathematical symbols on paper.

We may even play around with words.

But most thinking takes place within our minds, using our ability to ‘project’.

What you project in your mind is not always right.

You may have left out something very important.

You may have insufficient knowledge or experience of the subject.

You should never be arrogant or dogmatic—about your ‘projections’.

Be willing to accept that they may be wrong or limited.

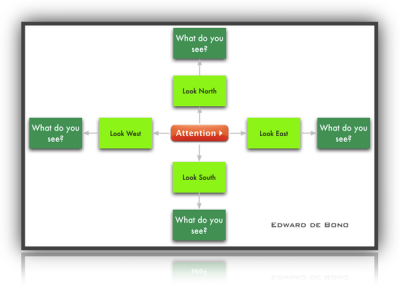

Attention Directing in depth

▪ What time is it?

▪ ’How old are you?

▪ ’Did you like the soup?

▪ ’Do you want some more coffee?

▪ ’What is the current exchange rate between the US dollar and the Japanese yen?

▪ ’At what temperature does this plastic melt?

All questions are attention-directing devices.

We could easily drop out ‘questions’ and instead ask people to direct their attention to specified matters.

▪ ’Direct your attention to the time.’

▪ ’Tell me the time.’

▪ ’Direct your attention to your age and tell me what you find.’

▪ ’Direct jour attention to the melting-point of this plastic and tell me what you know.’:

An explorer returns from an expedition to a newly discovered island.

The explorer reports on a smoking volcano and a bird that could not fly.

But what else was there?

The explorer explains that those were the two things that caught his attention.

That was not good enough.

So the explorer was sent back with specific instructions to use a very simple attention-directing framework.

‘Look north and note what you see.

Then look east and note what you see.

Then look south and note what you see.

Then look west and note what you see.

Larger view

Now come back and give us your NOTEBOOK.’

The N-S-E-W instructions provided a very simple framework for directing attention.

We look and then notice, and note

what we #SEE

in the direction

to which our attention is drawn

The brain can only SEE

what it is prepared to see

Six Frames for Thinking about Information

Our attention usually flows in three ways:

What catches our interest or emotional involvement at the moment.

Habits of attention established through experience and practice.

A more or less haphazard drift from one point to another.

A great many of the deliberate processes of thinking involve a specific direction of attention.

Socratic questioning (Drucker) is just such a direction of attention.

There is nothing magical about it.

The CoRT Thinking Programme for schools (to be described later) includes a number of attention-directing tools.

For example the OPV tool asks the thinker to direct his or her attention to the views of the other people involved.

Some thinkers might have done this automatically.

Most do not.

So there is a need for a deliberate attention-directing tool.

The important process of analysis is an attention-directing instruction.

▪ ’Direct your attention to the component parts making up this situation.’

▪ ’Direct your attention to the different influences affecting the price of oil.’

▪ ’Direct your attention to the various factors involved in the effectiveness of a police operation.’

▪ ’Direct your attention to the parts making up a skateboard?

▪ ’Direct your attention to the ingredients of our current strategy.’

Comparison is another fundamental ‘attention-directing instruction’.

▪ ’Direct your attention to the points of similarty between these two proposals.’

▪ ’Direct your attention to the points of similarity and the points of difference between the two pipes of packaging.’

▪ ’Direct your attention to the relative advantages and disadvantages of these two routes to the seaside.’

▪ ’Compare these two microwave ovens. Direct your attention to how they compare on price, capacity, reputation of maker, service, etc.’

For attention-directing we can use a deliberate external framework (as with the CoRT tools) or we can use simple internal instructions such as analyse and compare.

Another form of attention-directing is the request to focus on some aspect of a situation.

▪ ’I want you to focus on the political effect of raising the tax on diesel oil.’

▪ ’I want you to focus on the security, arrangements at the banquet.’

▪ ’I want you to focus on who is going to exercise this dog you want to buy.’

▪ ’I want you to focus on the benefits of going to a technical college.’

▪ ’I want you to focus on the disadvantages of taking this fired-interest mortgage.’

In the Six Thinking Hats framework (to be discussed later) this focusing is obtained by an external framework.

For example, use of the ‘yellow hat’ implies an exclusive focus on the values and benefits in the situation under discussion.

Use of the ‘black hat’ implies an exclusive focus on the dangers, problems, drawbacks and caution points.

Although most people claim to carry out attention-directing internally, in practice they do not.

For example, in a group of highly educated executives one half were asked to judge a suggestion objectively and the other, random, half were asked to use the yellow and black hats, deliberately.

Those using the hats turned up three times as many points as the others.

Yet most of the others would claim always to look at the ‘pros and cons’ in any situation.

That is why it is sometimes necessary to have external, formal and deliberate attention-directing tools.

They may seem simple and obvious but they are effective.

Recognition and Fit

A common child’s activity toy consists of a box or board with different-shaped holes in it.

The child is required to put different-shaped blocks or pieces into the different-shaped holes.

Some fit and some do not fit.

Someone is coming towards you from a distance.

You have no reason to expect a particular person.

As the person gets closer you begin to think that you might recognize her.

She gets close and suddenly you are sure: recognition ‘clicks’; there is a ‘fit.’

A wine expert tastes wine from a bottle with a masked label.

After a while she declares that it is from the Casablanca region in Chile.

Recognition and identification have taken place.

The brain forms patterns from experience.

Actually experience self-organizes itself into patterns within the brain.

That is why we can get dressed in the morning.

Otherwise we might have to explore the 39,816,800 ways of getting dressed with just eleven items of clothing.

Without patterns we could not cross the road or drive or read or write or do anything useful at work.

The brain is a superb pattern-making and pattern using system (which is why it is so bad at creativity).

We seek to fit things into the appropriate pattern.

We seek to use the boxes and definitions derived from experience —just as Aristotle wanted us to do.

We usually call this recognition, identification or judgement.

Mostly it is extremely useful.

Occasionally it is dangerous, when we trap something in the wrong box or when we seek to use old-fashioned boxes on a changed world.

We set out to look for something.

We are very happy when we find something that ‘fits’ what we are looking for.

We look no further.

There is a sort of ‘click’ about recognition.

This really means that we have switched into a well established pattern and are no longer ‘wandering around’.

I prefer the word ‘fit’ to the word ‘judgement’ because judgement has a much wider meaning.

Judgement may mean evaluation and assessment, which are specific attention-directing processes.

The word ‘fit’ is closer to ‘recognition’.

In some ways the purpose of thinking is to abolish thinking.

Some people have succeeded in this.

The purpose of thinking is to set up routine patterns so that we can always see the world through these routine patterns, which then tell us what to do.

Thinking is no longer needed.

Some people have succeeded in this because they believe that the patterns they have set up are going to be sufficient for the rest of their lives.

There is no prospect of change or progress for such people.

But they may be complacent and content.

In thinking we try to move towards ‘recognizing’ patterns.

We note when we have a recognition.

We also need to note the value — or danger — of that recognition.

Using stereotypes of people or races is a form of recognition but one that is more harmful than useful.

Movement and Alternatives

The basic thinking processes mentioned up to this point will be familiar to most traditional thinkers but movement will not be familiar.

‘Movement’ simply means ‘How do you move forward from this position?’

In its most extreme form movement is used along with provocation as one of the basic techniques of lateral (creative) thinking.

In a provocation we can set up something which is totally outside our experience and even contrary to experience.

As a provocation we might say: ‘Cars should have square wheels.’

Judgement would tell us that this is nonsense:

▪ it is structurally unsound;

▪ it would use more fuel; it would, shake to pieces; speed would be very limited;

▪ tremendous power would be needed; the ride would be most uncomfortable, etc., etc.

Obviously, judgement would not help us to use that provocation because judgement is concerned with past experience whereas creativity is concerned with future possibility.

So we need another mental operation and this is called ‘movement’.

How do we move forward from the provocation?

We might get movement from imagining the square wheel rolling (the projection process).

As the wheel rises on the corner point the suspension could adjust and get shorter so the car remained the same distance from the ground.

From this comes the concept of suspension that reacts in anticipation of need.

This leads on to the idea of ‘active’ or ‘intelligent suspension’, which is now being worked out as a real possibility.

Movement covers all ways of moving forwards from a statement, position or idea.

Movement can include association.

We move from one idea to an association.

Movement can include drift or day-dreaming, in which ideas just follow one another.

Movement also includes the setting up of alternatives.

If we have one satisfactory way of doing something why should we seek out alternatives?

There is no logical reason therefore we have to make a deliberate effort to generate parallel alternatives.

This involves movement: ‘How else can we do this?’

The value of seeking further alternatives is obvious.

The first way is not necessarily the best way.

A range of alternatives allows us to compare and assess them and choose the best.

‘Movement’ may be directed by an instruction or attention-directing request.

We may instruct ourselves to direct attention to ‘other members of the same class’.

So we move to these other members.

Movement is a very broad process and overlaps with other processes.

Movement is also the basis of ‘water logic’ which is described in my book Water Logic.

In water logic we observe the natural flow from one idea to another.

In the more deliberate process of movement we seek to bring about movement from one idea to another.

▪ ’Where do we go to/from here?’

▪ ’What alternatives are there?’

▪ ’How do we get movement from this provocation?’

▪ ’What follows?’

▪ ’What idea comes to mind?’

It could be said that the whole of thinking is an effort to get ‘movement’ in a useful direction.

We use many devices for that purpose.

There can be a value, sometimes, in having a simple way of describing a thinking situation or thinking need to yourself or to others.

‘It is this type of situation.’

‘This is the sort of thinking that is required.’

‘How would you describe the situation?

‘What thinking do we need here?

In this section I intend to describe a simple type of situation coding.

This is a subjective coding and is not a formal classification of situations.

You use this coding to indicate how the situation seems to you.

Someone else might disagree and then you can both focus on the disagreement.

Even though you may start out coding a situation one way, you may find that you need to modify the code as you go along.

The Coding

For each of the five stages of thinking (TO, LO, PO, SO, GO) you apply a number from 1 to 9.

This ‘rating’ from 1 to 9 indicates the amount, the difficultly or the importance of the thinking that needs to be done in that stage.

For example, if you are asked to choose between a fixed set of alternatives then the PO stage does not require much thinking because the alternatives have been given.

So the PO stage gets a 1.

On the other hand, the SO stage is going to have to do a lot of work so this stage gets a 9.

The GO stage may also have quite a lot to do and gets a 6.

The TO stage does not require much work because the thinking purpose has been clearly set, so the TO stage gets a 1.

The LO stage is important because you need to explore perceptions and find information in order to make your choice.

So the LO stage gets an 8.

The overall coding now becomes 18/196. The break after the first two digits is for ease of pronunciation: one eight / one nine six.

In another situation there seems to be confusion.

The information is present but you do not know what to do.

Perhaps the emotional factor is high.

The emphasis may now fall on the TO stage.

‘Am I clear as to what I want to achieve?

What is the real purpose of my thinking?

With what do I want to end up?

So the TO stage gets a 9. The information is mostly available, so the LO stage gets a 4.

The PO stage does require some work but if the TO stage is clear then the PO stage will not be difficult.

So the PO stage also gels a 4.

The SO stage may be important, especially if there is emotional involvement, so this stage gets a 6.

The GO stage may be straightforward and gets a 1.

So the final coding becomes: 94/461 (nine four / four six one).

On another occasion the sole purpose of the thinking is to obtain a specific piece of information.

The TO stage is clear, so this gets a 1.

The LO stage is all important and gets a 9.

The PO stage is also important because we may have to consider possible ways of getting the information.

So the PO stage gets an 8.

The SO stage may be simple if there turns out to be one clear way of getting the information.

But this may not be clear and there may be several ways to choose between.

So the SO stage gets a 5.

The GO stage is relatively simple and gets a 4.

The overall coding becomes: 19/854 (one nine / eight five four).

Another situation is a direct creative demand.

You are asked to come up with a good name for a book.

The purpose of the thinking is very clear, so the TO stage gets a 1.

The information stage is important because you need to know what is in the book, who it is meant to appeal to and where it will be sold.

You also need to know the titles of other books on the same subject.

So the LO stage is important and gets an 8.

Obviously, most of the work is going to be creatively in the PO stage, so this gets a 9.

The choice stage is going to be difficult.

How do we decide which title to use?

So the SO stage also gets an 8.

The GO stage is simple because if you have selected the title you simply use that title.

So the GO stage gets a 1.

The resulting coding is: 18/981 (one eight / nine eight one).

Only use the 9 rating once in the coding even if two stages both seem very important.

The 9 should indicate the most important stage.

The other figures should be used as often as you like.

Of course, all stages of thinking are important and you may be inclined to give a high rating to each of the five stages.

This would be to misunderstand the purpose of the coding.

A stage with a low rating does not mean that stage is unimportant.

It means that that stage will require less thinking work than other stages.

It is relative.

If you are set a specific task then the TO stage is simple.

If you simply wish to make a choice then the GO stage may be simple.

If you are working in a closed problem where all the information is available then the LO stage may be simple.

If you are presented with fixed alternatives then the PO stage may be simple.

If you clearly identify a situation in the PO stage then the SO stage may be simple.

In a negotiation situation the purpose may be clear: ‘We want to end up with an agreement acceptable by both sides.’

So the TO stage is simple and gets al.

The information stage may have to explore a lot of information.

There will also be a need to explore values, fears, perceptions, etc.

So this stage will be important and the LO stage gets an 8.

The PO stage is key because it is here that the ‘design’ of possible outcomes has to be worked out.

There will need to be a lot of activity here.

So the PO stage gets the 9.

It is difficult to predict how much work will need to be done in the SO stage.

If one of the possible designs put forward in the PO stage is very good then there will not be much difficulty choosing this outcome.

But if there is no one outstanding design then the choice process is going to be hard work.

So the SO stage gets an 8.

The desired outcome of the thinking is an acceptable agreement.

But some thinking should also be given to its implementation.

So the GO stage gets a 5.

The final coding becomes: 18/985 (one eight / nine eight five).

If there is a problem to be solved then you may need to spend time defining and redefining the problem.

So the TO stage should not be automatic and deserves a 6.

This is particularly so if the problem has been around for a long time.

If the problem has been around for a long time the information may be well known, so the LO stage may also get a 6.

The generative effort has to take place in the PO stage so this gets the 9.

The SO stage may be simple if a solution has turned up in the PO stage.

If no solution has turned up then the 80 stage is also simple because all possibilities will be rejected.

So the SO stage gets a 5.

The implementation of the solution needs thinking through, so the GO stage gets a 7.

The final coding becomes: 66/957 (six six / nine five seven).

Should Be

The coding is not just a simple description of what is the case but an indication of what you believe the situation ‘should be’.

When you are given a problem to solve, the definition of the problem may also be given to you.

This could mean that the TO stage only merits a 1.

But if you feel that much more attention should be given to defining, redefining and even breaking down the problem then you should indicate a 7 or an 8- in some cases even the 9.

In this way the suggested coding becomes not only an indication of the situation but also a ‘strategy’ for dealing with the situation.

If you really feel that a thorough information search is going to solve the problem then you would want to give the 9 to the LO stage.

If you really feel that only creative effort will solve the problem then you give the 9 to the PO stage.

If you feel that there are already enough possibilities and choice is required then you give the 9 to the SO stage.

If you feel that the action design will be most important (an acceptance difficulty) then the GO stage gets the 9.

A 91/811 situation means that the thinker believes that a clear definition of the thinking purpose is all important.

The information is simple and available.

There is a need to generate possibilities.

The thinker believes that a satisfactory possibility will be forthcoming so the SO and GO stages will be simple.

An 18/195 situation seems to be a decision situation: perhaps a go/no go situation.

The purpose is clear.

Information is important.

There is little need to generate possibilities.

The SO stage is all-important and the action stage is moderately important.

Summary

In this section I have suggested a simple form of descriptive coding for thinking situations.

This coding consists of assigning a 1 to 9 rating to each of the five stages of thinking.

The higher the rating the more ‘thinking work’ there is to be done in this stage.

The coding indicates what you think should be the case.

The coding indicates your intended thinking strategy.

You can use the coding to describe a thinking need to yourself or to describe it to others.

The coding becomes a way of thinking about and talking about a whole situation.

TO ‘Where am I going to?’

What is the purpose of my thinking?

With what do I want to end up?

This stage of thinking is very important indeed.

We usually give this stage too little attention.

We need to be very clear on what we are thinking about and what we want to achieve.

We need to define and redefine the purpose.

We need to seek alternative definitions.

We may want to break down the purpose into smaller ones.

There are two main types of purpose or focus.

In the traditional purpose focus we set out what we want to achieve.

This may be solving a problem, achieving an objective, carrying out a task or making an improvement in a defined direction.

In the area focus, we simply define the area in which we are looking for new ideas.

Keep very clearly in mind that solving problems and putting right defects is only one aspect of thinking.

There is far more to thinking than problem solving.

LO ‘Lo and behold.’

What can we see?

What should we look for?

In this stage we seek to gather and to lay out the information we need for our thinking.

The search for information should be very broad at times but at other times it may need to be focused.

There are fishing questions, where we do not know what answer will emerge.

There are shooting questions, where the answer is a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’ and we are checking things out.

Sometimes we need a guess or a hypothesis in order to know where to look.

Use such guesses but be careful not to be trapped by them.

Perceptions and values are an important part of this stage.

What are the different perceptions?

How can things be looked at differently?

What values are involved?

Do different people have different values?

What is the thinking of different people?

PO ‘Let’s generate some possibilities.’

This is the creative, productive and generative stage of thinking.

It is in this stage that we put forward ‘possibilities’.

It is this stage which links up the purpose of our thinking with the output of our thinking.

There are two thinking stages before and two afterwards.

This stage is the link between input and output.

There are four broad approaches that can be used in the PO stage.

1. Search for routine.

Here we seek to identify the situation so that we can then know what to do and can apply the action that has been established as the routine response to that situation.

This is the traditional approach to thinking.

2. General approach.

Here we link starting-point and desired result with a broad, ‘general’ concept.

Then we seek to narrow this down to give us specific ideas that we can use.

The Concept Fan is part of this approach.

We work backwards, in general terms, from where we want to be in order to produce ideas that we can use.

3. Creative approach.

Here we set out deliberately to generate ideas and then we seek to modify these ideas to fit our needs.

There are the formal techniques of lateral thinking such as provocation and the use of a random entry.

‘Movement’ is a key part of creative thinking.

We ‘move’ forward from a provocation to get a useful idea.

4. Design and assembly.

Here we lay out the needs and ingredients in parallel.

Then we seek to design a way forward to achieve the ‘design brief’.

We seek to assemble or to put things together to give us what we want.

The purpose of the PO stage is to be generative and to produce multiple possibilities.

SO ‘So what is the outcome?’

The purpose of the SO stage is to take the multiple possibilities produced by the PO stage and to reduce these to a usable outcome.

There is the development stage, in which we seek to build up and improve ideas.

We seek to remove defects.

Then there is the evaluation and assessment stage, in which we examine each idea.

We seek to list the benefits and values.

We seek to list the difficulties and problems.

Next is the choice stage.

We now lay out all the competing ideas and choose between them.

There are various methods for making this choice.

We may use one method to narrow down the number of alternatives and then use direct comparison.

The decision process is concerned with whether or not we do something.

We need to consider the decision frame and the pressures.

We must consider the need for the decision.

We must consider the risks.

At the end of the SO stage we may have an idea we want to use or we may have nothing.

GO ‘Go to it!’

The GO stage is concerned with action.

How is the chosen idea going to be put into action?

What is the action design?

There are stages and sub-objectives.

There is the need to monitor and to check.

We use routine channels and we assess the uncertainties with if-boxes.

The people factor in its various forms is a key part of action.

People need persuading.

Ideas must be accepted.

There is a need for motivation.

People can be obstructive.

All these things need to be considered.

There is also the need to design in the energy of action.

Where is this to come from?

![]()