|

What executives should remember

(core work toward)

“Management’s concern and management’s responsibility are everything

that affects the performance of the institution and

its results—whether inside or outside,

whether under the institution’s control

or totally beyond it.” — Management’s new paradigm

The change leader

Without the institution, there would be no management.

But without management, there would be only a mob rather than an institution.

(core work toward)

The institution is itself an organ of society and exists only to contribute a needed result to society, the economy, and the individual.

Organs, however, are never defined by what they do, let alone by how they do it.

They are defined by their contribution.

And it is management that enables the institution to contribute.

“The customer never buys what you think you sell.

And you don’t know it.

That’s why it’s so difficult to differentiate yourself.” — Drucker

§§§

All our experience tells us that the customer never buys what the supplier sells

Value to the customer is always something fundamentally different from what is value or quality to the supplier

This applies as much to a business as it applies to a university or to a hospital

See marketing

(core work toward)

Indeed, the first task of management is to define what results and performance are in a given organization — and this, as anyone who has worked on this task can testify, is in itself one of the most difficult, one of the most controversial, but also one of the most important tasks

It is, therefore, the specific function of management to organize the resources of the organization for results outside the organization

From chapter 44 of Management, Revised Edition

We no longer need to theorize about how to define performance and results in the large enterprise.

Rather, they maximize the wealth-producing capacity of the enterprise.

It is this objective that integrates short-term and long-term results and that ties the operational dimensions of business performance—market standing, innovation, productivity, and people and their development—to financial needs and financial results.

It is also this objective on which all constituencies depend for the satisfaction of their expectations and objectives, whether shareholders, customers, or employees.

To define performance and results as maximizing the wealth-producing capacity of the enterprise may be criticized as vague.

To be sure, one doesn’t get the answers by filling out forms.

Decisions need to be made, and economic decisions that commit scarce resources to an uncertain future are always risky and controversial.

Financial objectives are needed to tie all this together.

Indeed, financial accountability is the key to the performance of management and enterprise.

Without financial accountability, there is no accountability at all.

And without financial accountability, there will also be no results in any other area.

What we have is not the “final answer.”

Still, it is no longer theory but proven practice.

... snip, snip ...

For while the business audit need not be conducted every year (every three years may be enough in most cases), it needs to be based on predetermined standards and go through a systematic evaluation of business performance, starting with mission and strategy, through marketing, innovation, productivity, people development, community relations, all the way to profitability.

Still, the question remains, Who is going to use this tool?

In the American context, there is only one possible answer: a revitalized board of directors

(core work toward)

… Of course, it is always important to adapt to economic changes rapidly, intelligently, and rationally.

But managing implies responsibility

for attempting to shape the economic environment;

for planning, initiating, and carrying through changes in that economic environment;

for constantly pushing back the limitations of economic circumstances on the enterprise’s ability to contribute.

What is possible—the economist’s “economic conditions”—is therefore only one pole in managing a business.

What is desirable in the interest of economy and enterprise is the other.

And while humanity can never really “master” the environment, while we are always held within a tight vise of possibilities, it is management’s specific job to make what is desirable first possible and then actual.

Management is not just a creature of the economy; it is a creator as well.

And only to the extent to which it masters the economic circumstances, and alters them by consciously directed action, does it really manage.

To manage a business means, therefore, to manage by objectives

Chapter 3, Management, Revised Edition

The Management Revolution from Post-Capitalist Society

Supplying knowledge to find out how existing knowledge can best be applied to produce results is, in effect, what we mean by management.

But knowledge is now also being applied systematically and purposefully to define what new knowledge is needed, whether it is feasible, and what has to be done to make knowledge effective.

It is being applied, in other words, to systematic innovation.

Most people when they hear the word “management” still hear “business management.”

But we soon learned that management is needed in all modern organizations.

In fact, we soon learned that it is needed even more in organizations that are not businesses, whether not-for-profit but non-governmental organizations (what in this book I propose we call the “social sector”) or government agencies.

These organizations need management the most precisely because they lack the discipline of the “bottom line” under which business operates.

That management is not confined to business was recognized first in the United States.

But it is now becoming accepted in every developed country.

We now know that management is a generic function of all organizations, whatever their specific mission.

It is the generic organ of the knowledge society.

Management has been around for a very long time.

I am often asked whom I consider the best or the greatest executive.

My answer is always: “The man who conceived, designed, and built the first Egyptian Pyramid more than four thousand years ago—and it still stands.”

But management as a specific kind of work was not seen until after World War I—and then by just a handful of people.

Management as a discipline only emerged after World War II.

As late as 1950, when the World Bank began to lend money for economic development, the word “management” was not even in its vocabulary.

With this powerful expansion of management came a growing understanding of what management really means.

When I first began to study management, during and immediately after World War II, a manager was defined as “someone who is responsible for the work of subordinates.”

A manager in other words was a “boss,” and management was rank and power.

This is probably still the definition a good many people have in mind when they speak of “managers” and “management.”

But by the early 1950s, the definition of a manager had already changed to one who “is responsible for the performance of people.”

Today, we know that that is also too narrow a definition.

The right definition of a manager is one who “is responsible for the application and performance of knowledge.”

This change means that we now see knowledge as the essential resource.

Land, labor, and capital are important chiefly as restraints.

Without them, even knowledge cannot produce; without them, even management cannot perform.

But where there is effective management, that is, application of knowledge to knowledge, we can always obtain the other resources.

That knowledge has become the resource, rather than a resource, is what makes our society “post-capitalist.”

This fact changes—fundamentally—the structure of society. This fact changes—fundamentally—the structure of society.

It creates new social and economic dynamics. It creates new social and economic dynamics.

It creates new politics. It creates new politics.

The Function Of Organizations

The function of organizations is to make knowledges productive.

Organizations have become central to society in all developed countries because of the shift from knowledge to knowledges.

The more specialized knowledges are, the more effective they will be.

The best radiologists are not the ones who know the most about medicine; they are the specialists who know how to obtain images of the body's inside through X-ray, ultrasound, body scanner, magnetic resonance.

The best market researchers are not those who know the most about business, but the ones who know the most about market research.

Yet neither radiologists nor market researchers achieve results by themselves; their work is “input” only.

It does not become results unless put together with the work of other specialists.

Knowledges by themselves are sterile.

They become productive only if welded together into a single, unified knowledge.

To make this possible is the task of organization, the reason for its existence, its function.

Peter Drucker, Post-Capitalist Society

In the knowledge society, it is not the individual who performs.

The individual is a cost center rather than a performance center.

It is the organization that performs.

(Across multiple time dimensions:

explore the life stories of HP, Kodak, RIM or RCA)

— A Century of Social Transformation by Peter Drucker

“The productivity of knowledge is going to be the determining factor

in the competitive position of a company, an industry, an entire country.

No country, industry, or company has any “natural” advantage or disadvantage.

The only advantage it can possess is the ability to exploit universally available knowledge.

The only thing that increasingly will matter

in national as in international economics

is management’s performance in making knowledge productive.”

— Knowledge: Its Economics and Productivity

Because the knowledge society

perforce has to be

a society of organizations,

its central and distinctive organ is

management.

When we first began to talk of management, the term meant “business management” — since large-scale business was the first of the new organizations to become visible.

But we have learned this last half-century that management is the distinctive organ of all organizations.

All of them require management—whether they use the term or not.

All managers do the same things whatever the business of their organization.

All of them have to bring people—each of them possessing a different knowledge—together for joint performance.

All of them have to make human strengths productive in performance and human weaknesses irrelevant.

(He is separating two different dimensions of individuals — their knowledges and their strengths)

All of them have to think through what are “results” in the organization—and have then to define objectives.

How to guarantee non-performance How to guarantee non-performance

Management by Objectives — a user’s guide Management by Objectives — a user’s guide

Find “objectives” on this page

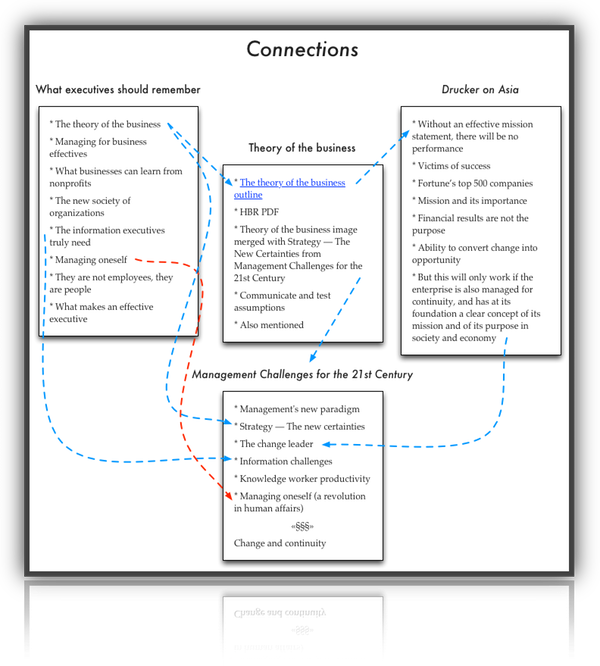

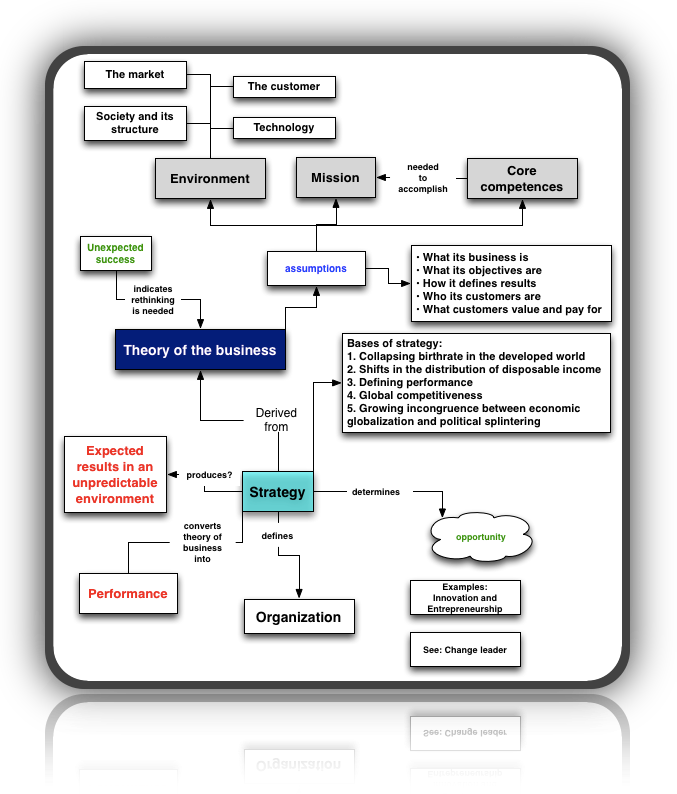

All of them are responsible to think through what I call the “theory of the business,” that is, the assumptions on which the organization bases its performance and actions, and equally, the assumptions which organizations make to decide what things not to do (abandonment).

Communicate and Test Assumptions

The theory of the business must be known and understood throughout the organization.

This is easy in an organization’s early days.

But as it becomes successful, an organization tends increasingly to take its theory for granted, becoming less and less conscious of it.

Then the organization becomes sloppy.

It begins to cut corners.

It begins to pursue what is expedient rather than what is right.

It stops thinking.

It stops questioning.

It remembers the answers but has forgotten the questions.

The theory of the business becomes “culture.”

But culture is no substitute for discipline, and the theory of the business is a discipline.

The theory of the business has to be tested constantly.

It is not graven on tablets of stone.

It is a hypothesis.

And it is a hypothesis about things that are in constant flux—society, markets, customers, technology.

And so, built into the theory of the business must be the ability to change itself.

Some theories are so powerful that they last for a long time.

Eventually every theory becomes obsolete and then invalid.

It happened to the GMs and the AT&Ts.

It happened to IBM.

It is also happening to the rapidly unraveling Japanese keiretsu.

4 JUL The Daily Drucker

All of them require an organ that thinks through strategies, that is, the means through which the goals of the organization become performance.

All of them have to define the values of the organization, its system of rewards and punishments, and with its spirit and its culture.

In all of them, managers need both

the knowledge of management as work and discipline,

and

the knowledge and understanding of the organization itself

its purposes,

its values,

its environment and markets,

its core competencies.

— A Century of Social Transformation by Peter Drucker

Management and Entrepreneurship

… It should have been obvious from the beginning that management and entrepreneurship are only two different dimensions of the same task.

An entrepreneur who doesn’t learn how to manage will not last long.

A management that does not learn to innovate will not last long.

Every institution—and not only business—must build into its day-to-day management four entrepreneurial activities that run in parallel.

One is the organized abandonment of products, services, processes, markets, distribution channels and so on that are no longer an optimal allocation of resources.

This is the first entrepreneurial discipline in any given situation.

Then any institution must organize for systematic, continuing improvement (what the Japanese call kaizen).

Then it has to organize for systematic and continuous exploitation, especially of its successes.

It has to build a different tomorrow on a proven today.

And, finally, it has to organize systematic innovation, that is, to create the different tomorrow that makes obsolete and, to a large extent, replaces even the most successful products of today in any organization.

See innovation in the existing organization requires special effort

I emphasize that these disciplines are not just desirable, they are three conditions for survival today.

These entrepreneurial tasks differ from the more conventional management roles of allocating present-day resources to present-day demands.

These entrepreneurial activities start with the outside and are focused on the outside.

But the tools we originally fashioned to bring the outside to the inside have all been penetrated by the inside focus of management.

They have turned into tools to enable management to ignore the outside.

Even worse, they are used to make management believe it can manipulate the outside and turn it to the organization’s purpose.

Take marketing

The term was coined 50 years ago to emphasize that the purpose and results of a business lie entirely outside of itself.

Marketing teaches that organized efforts are needed to bring an understanding of the outside, of society, economy and customer, to the inside of the organization and to make it the foundation for strategy and policy.

Yet marketing has rarely performed that grand task.

Instead it has become a tool to support selling.

It does not start out with “who is the customer?” but “what do we want to sell?”

It is aimed at getting people to buy the things that you want to make.

That’s getting things backward.

American industry lost the fax machine business that way.

The question should be “how can I make things the customers want to buy.”

Executives of any large organization—whether business enterprise, Roman Catholic diocese, university, health care institution, government agency—are woefully ignorant of the outside, as everybody knows who has worked with decisions in a large organization.

These executives must spend too much of their time and energy managing inwardly rather than managing outwardly.

The inward focus of management has been aggravated rather than alleviated in the last decades by the rise of information technology.

Information technology so far may well have done serious damage to management because it is so good at getting additional information of the wrong kind.

Based upon the 700-year-old accounting system designed to record and report inside data, information technology produces more data about the inside.

It produces practically no information about anything that goes on outside of the enterprise.

Practically every conference on information deals exclusively with how to get more inside data.

I have yet to hear of one that even raises the question: “What outside data do we need, and how do we get them?”

Management does not need more information about what is happening inside.

It needs more information on what is happening outside.

So far no one has figured out how to get meaningful outside data in any systematic form.

When it comes to outside data, we are still very largely in the anecdotal stage.

It can be predicted that the main challenge to information technology in the next 30 years will be to organize the systematic supply of meaningful outside information.

It is understandable that management began as a concern for the inside.

When the first large, modern organizations first arose—around 1870—the first and by far the most visible need was to organize the enterprise itself.

Nobody had ever done it before on that scale.

But now we know how to do that.

Growth and survival both now depend on getting the organization in touch with the outside world.

Management has become an external, not an internal, task.

For results take place outside the organization.

Inside, there are only costs.

Larger

It is the very nature of knowledge

that it changes fast and

that today's certainties

will be tomorrow's absurdities. — Peter Drucker

Purpose and Objectives First

To Drucker, strategy, like everything else in management, is a thinking person’s game.

It isn’t arrived at by following some rigid set of rules but by thinking through various aspects of the business.

It all starts with objectives.

How to guarantee non-performance How to guarantee non-performance

Management by Objectives — a user's guide Management by Objectives — a user's guide

“Only a clear definition of the mission makes possible clear and realistic business objectives.

It is the foundation for priorities, strategies, plans and work assignments.

It is the starting point for the design of managerial jobs, and, above all, for the design of managerial structures.

Structure follows strategy.

Strategy determines what the key activities are in a given business.

And strategy requires knowing what our business is and what it should be.

Chapters on “What is a Business” and “Business Purpose and Business Mission” in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices and Chapters 8 and 9 in Management, Revised Edition

Drucker also explained that “nothing may seem simpler or more obvious than to answer what a company’s business is.

A steel mill makes steel, a railroad runs to carry freight and passengers … .

Actually ‘what is our business?’ is almost always a difficult question which can be answered only after hard thinking and studying.

And the right answer is usually anything but obvious.”

Thinking back to Drucker’s Law, no strategy can be created without the customer, for it is the customer who defines business purpose.

And “therefore the question ‘what is our business?’ can be answered only by looking at the business from the outside, from the point of view of the customer and the market.

What the customer sees, thinks, believes and wants at any given time must be accepted by management as an objective fact deserving to be taken as seriously” as any hard data collected from salespeople, accountants, or engineers, contended Drucker.

Drucker claimed that the single most important cause of business failure can be attributed to management’s failure to ask the question “what is our business?” in a “clear and sharp form.”

And it isn’t only when a company is starting out that the question should be asked, or when the company is in trouble.

“On the contrary,” Drucker wrote, “to raise the question and to study it thoroughly is most needed when a business is successful.

For then failure to raise it may result in rapid decline.”

— Inside Drucker's Brain

A product or service name is never an effective answer to these questions because it doesn’t specify the specific contribution to the customer that matches what customers value and pay for — they buy what it does for them. See “The Customer: Joined at the Hip” in The Definitive Drucker and “Changing Values and Characteristics (creating a customer)” in Innovation and Entrepreneurship — bobembry

See Chapter 44

“The Impact of Pension Funds on Corporate Governance” in

Management, Revised Edition

Analysis of the entire business and its basic economics always shows it to be in worse disrepair than anyone expected.

The products everyone boasts of turn out to be yesterday’s breadwinners or investments in managerial ego.

Activities to which no one paid much attention turn out to be major cost centers and so expensive as to endanger the competitive position of the company.

What everyone in the business believes to be quality turns out to have little meaning to the customer.

Important and valuable knowledge either is not applied where it could produce results or produces results no one uses.

I know more than one executive who fervently wished at the end of the analysis that he could forget all he had learned and go back to the old days of the “rat race” when “sufficient unto the day was the crisis thereof.”

But precisely because there are so many different areas of importance, the day-by-day method of management is inadequate even in the smallest and simplest business.

Because deterioration is what happens normally—that is, unless somebody counteracts it—there is need for a systematic and purposeful program.

There is need to reduce the almost limitless possible tasks to a manageable number.

There is need to concentrate scarce resources on the greatest opportunities and results.

There is need to do the few right things and do them with excellence.

Managing for Results by Peter Drucker

Broken Washroom Doors: Drucker said the problem of having people in positions where they do the least amount of good exists everywhere, but it is more rampant in hospitals, churches, and other nonprofits than in corporations.

To raise productivity in most any organization managers should regularly assess their key people, their strengths, and the results they achieve.

Then they should ask themselves:

Do we have the right people in the right jobs, where they can make the greatest contributions?

Are the jobs the right ones, meaning do we have people performing tasks that even if achieved do not add value to the organization?

What changes in people, jobs, and job functions can we make that will yield greater results?

Inside Drucker's Brain

The 90/10 Rule at Yum! Brands

But every analysis of actual allocation of resources and efforts in business that I have ever seen or made showed clearly that the bulk of time, work, attention, and money first goes to 'problems' rather than to opportunities, and, secondly, to areas where even extraordinarily successful performance will have minimal impact on results. (calendarize this?)

One of the hardest things for a manager to remember is that of the 1,000 different situations he or she will be asked to deal with on any given day, only the smallest handful have a shot at moving the enterprise forward in a truly significant way (calendarize this?)

The job of management, then, is to make sure that financial capital, technology, and top talent are deployed where most of the results are and where most of the costs aren't. The temptation often exists, however, to do exactly the opposite

High tech is living in the nineteenth century, the pre-management world. They believe that people pay for technology. They have a romance with technology. But people don't pay for technology: they pay for what they get out of technology. The Frontiers of Management

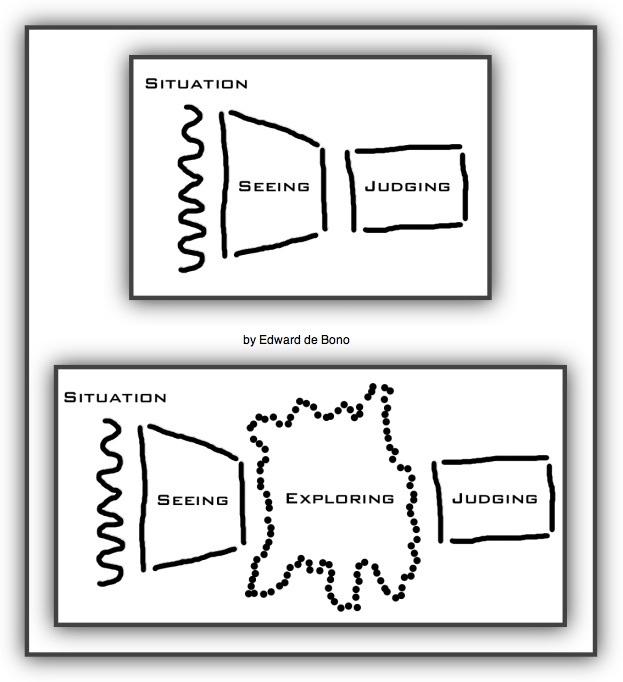

Many highly intelligent people use their thinking

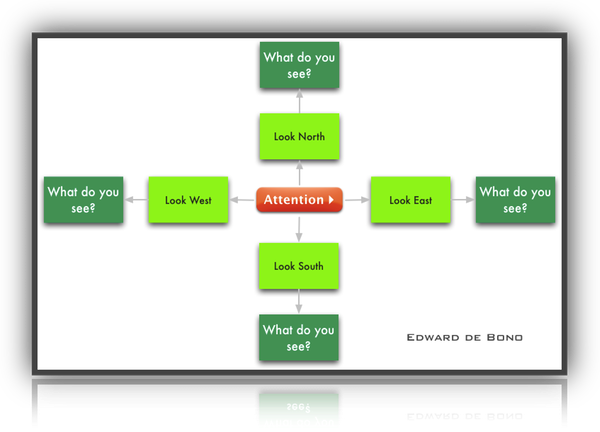

to back up or defend their immediate judgement of a matter.

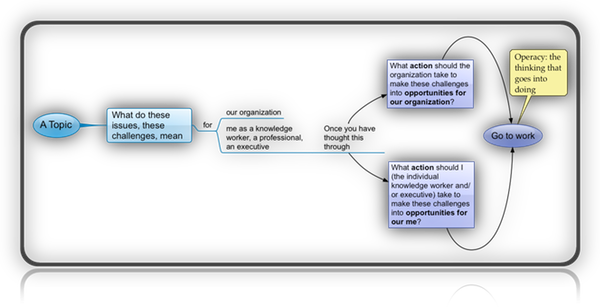

… a perception-broadening tool (attention-directing)

forces a thinker to explore the situation

before coming to a judgement — Edward de Bono

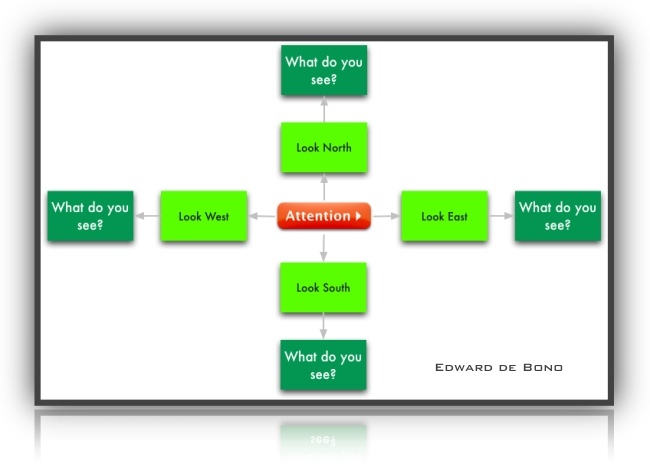

“To know something,

to really understand something important,

one must look at it from sixteen different angles.

People are perceptually slow,

and there is no shortcut to understanding;

it takes a great deal of time.” read more

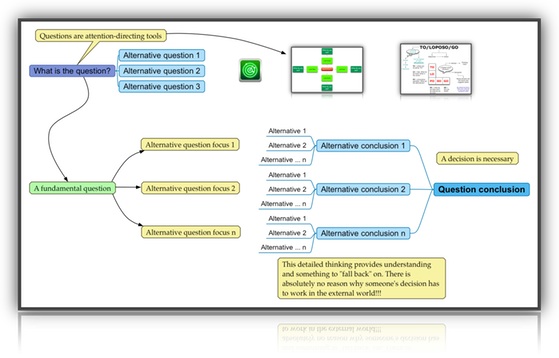

Attention directing is exploring

Questions are attention directing tools

Questions in The Definitive Drucker.

Social ecologists try to find the right questions

Using your ignorance to your benefit

What impact might an educated person add to the thinking?

Larger

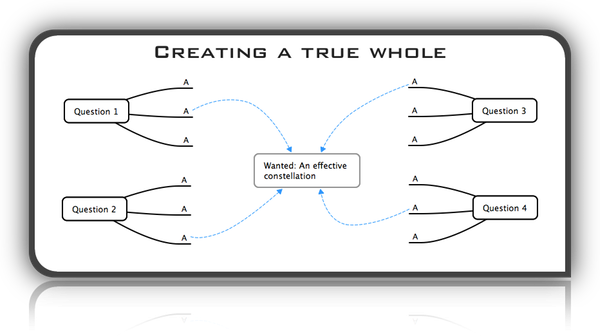

Effectively working on questions

requires a

foundation for future directed decisions

Sometimes alternative answers

need to be combined

to create an effective “constellation.”

Larger

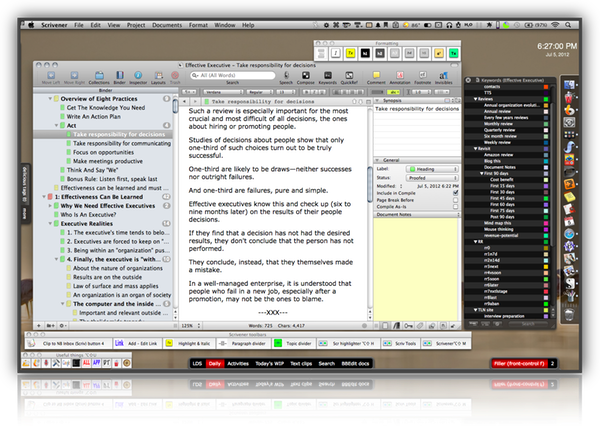

Dense reading and Dense listening

A tool for harvesting, collecting, and organizing “information”

Larger ::: Scrivener

Larger view of challenge thinking and an alternative — operacy

Dense reading and Dense listening

and Thinking broad and Thinking detailed

by Edward de Bono

Google site search: asking right questions

See Drucker books for more questions

The view of management presented above is the opposite of inside-out behavior …

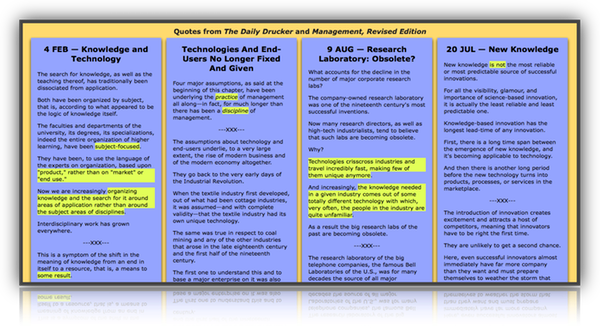

AS WE ADVANCE deeper into the knowledge economy, the basic assumptions underlying much of what is taught and practiced in the name of management are hopelessly out of date. (calendarize this?)

Amazon link: How The Mighty Fall

Only the Paranoid Survive

… the organization of the post-capitalist society of organizations

is a destabilizer.

Because its function is to put knowledge to work

—on tools, processes, and products;

on work;

on knowledge itself—

it must be organized for constant change.

It must be organized for innovation;

and innovation,

as the Austro-American economist

Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950) said,

is “creative destruction.”

It must be organized for systematic abandonment

of the established, the customary, the familiar,

the comfortable

— whether products, services, and processes,

human and social relationships, skills,

or organizations themselves.

It is the very nature of knowledge

that it changes fast and

that today's certainties

will be tomorrow's absurdities. — Peter Drucker

What Is Management?

From Management, Revised Edition

But what is management?

Is it a bag of techniques and tricks?

A bundle of analytical tools like those taught in business schools?

These are important, to be sure, just as a thermometer and anatomy are important to the physician.

But the evolution and history of management—its successes as well as its problems—teach that management is, above all else, a very few, essential principles.

To be specific:

Management is about human beings.

Its task is to make people capable of joint performance, to make their strengths effective and their weaknesses irrelevant. See chapter 27 — The Spirit of Performance

This is what organization is all about, and it is the reason that management is the critical, determining factor.

These days practically all of us, especially educated people, are employed by managed institutions, large and small, business and nonbusiness.

We depend on management for our livelihoods.

And our ability to contribute to society also depends as much on the management of the organization in which we work as it does on our own skills, dedication, and effort.

Because management deals with the integration of people in a common venture, it is deeply embedded in culture.

What managers do in West Germany, in Britain, in the United States, in Japan, or in Brazil is exactly the same.

How they do it may be quite different.

Thus one of the basic challenges managers in a developing country face is to find and identify those parts of their own tradition, history, and culture that can be used as management building blocks.

The difference between Japan’s economic success and India’s relative backwardness is largely explained by the fact that Japanese managers were able to plant imported management concepts in their own cultural soil and make them grow.

Every enterprise requires commitment to common goals and shared values.

Without such commitment, there is no enterprise.

There is only a mob.

The enterprise must have simple, clear, and unifying objectives.

The mission of the organization has to be clear enough and big enough to provide common vision.

The goals that embody it have to be clear, public, and constantly reaffirmed.

Management’s first job is to think through, set, and exemplify those objectives, values, and goals.

How to guarantee non-performance How to guarantee non-performance

What Results Should You Expect? — A Users' Guide to MBO What Results Should You Expect? — A Users' Guide to MBO

The Five Most Important Questions You Will Ever Ask About Your Organization The Five Most Important Questions You Will Ever Ask About Your Organization

Management must also enable the enterprise and each of its members to grow and develop as needs and opportunities change.

Every enterprise is a learning and teaching institution.

Training and development must be built into it on all levels—training and development that never stop.

Every enterprise is composed of people with different skills and knowledge doing many different kinds of work.

It must be built on communication and on individual responsibility.

All members need to think through what they aim to accomplish—and make sure that their associates know and understand that aim.

All have to think through what they owe to others—and make sure that others understand.

All have to think through what they, in turn, need from others—and make sure that others know what is expected of them.

Neither the quantity of output nor the “bottom line” is by itself an adequate measure of the performance of management and enterprise.

Market standing, innovation, productivity, development of people, quality, financial results—all are crucial to an organization’s performance and to its survival.

Nonprofit institutions, too, need measurements in a number of areas specific to their mission.

Just as a human being needs a diversity of measures to assess its health and performance, an organization needs a diversity of measures to assess its health and performance.

Performance has to be built into the enterprise and its management; it has to be measured—or at least judged—and it has to be continuously improved.

Finally, the single most important thing to remember about any enterprise is that results exist only on the outside.

The result of a business is a satisfied customer.

The result of a hospital is a healed patient.

The result of a school is a student who has learned something and puts it to work ten years later.

Inside an enterprise, there are only costs.

Managers who understand these principles and manage themselves in their light will be achieving, accomplished managers.

Management As A Liberal Art

Thirty years ago, the English scientist and novelist C. P. Snow talked of the “two cultures” of contemporary society.

Management, however, fits neither Snow’s “humanist” nor his “scientist.”

It deals with action and application; and its test is its results.

This makes it a technology.

But management also deals with people, their values, their growth and development—and this makes it a humanity.

So does its concern with and impact on social structure and the community.

Indeed, as has been learned by everyone who, like this author, has been working with managers of all kinds of institutions for long years, management is deeply involved in spiritual concerns—the nature of man, good and evil.

Management is thus what tradition used to call a liberal art:

“liberal” because it deals with the fundamentals of knowledge, self-knowledge, wisdom, and leadership;

“art” because it is practice and application.

Managers draw on all the knowledge and insights of the humanities and the social sciences—on psychology and philosophy, on economics and history, on ethics as well as on the physical sciences.

But they have to focus this knowledge on effectiveness and results—on healing a sick patient, teaching a student, building a bridge, designing and selling a “user-friendly” software program.

For these reasons, management will increasingly be the discipline and the practice through and in which the “humanities” will again acquire recognition, impact, and relevance.

Drucker’s Lost Art of Management: Peter Drucker’s Timeless Vision for Building Effective Organizations

Management, that is, the “useful knowledge” that enables man for the first time to render productive people of different skills and knowledge working together in an “organization,” is an innovation of this century.

It has converted modern society into something brand new, something, by the way, for which we have neither political nor social theory: a society of organizations. — Peter Drucker, Innovation and Entrepreneurship

For the first time in thousands of years, we face again a situation that can be compared with what our remote ancestors faced at the time of the irrigation civilization.

It is not only the speed of technological change that creates a revolution, it is its scope as well.

Above all, today, as seven thousand years ago, technological developments from a great many areas are growing together to create a new human environment.

This has not been true of any period between the first technological revolution and the technological revolution that got under way two hundred years ago and has still clearly not run its course. — Peter Drucker, Technology, Management and Society

… It also follows that managing a business must be a creative rather than an adaptive task. The more a management creates economic conditions or changes them rather than passively adapts to them, the more it manages the business — Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

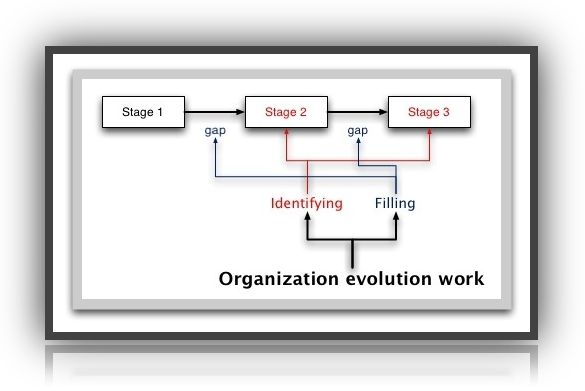

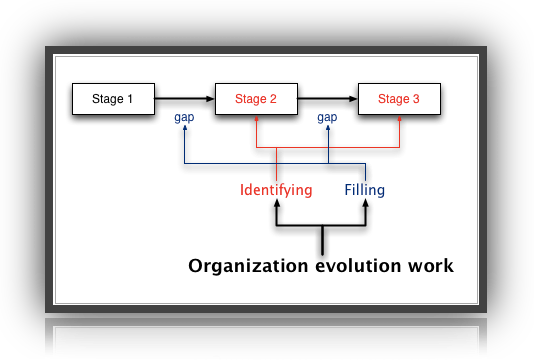

Organization evolution

Following is from Adventures of a Bystander

The knowledge society into which we are moving so fast is going to be a society of organizations.

But of organizations—plural—that will be diverse, decentralized, multiform.

And within these organizations, we are moving away from the standardized, uniform structures that were generally accepted in public administration and business management, “the one right structure for the typical manufacturing company,” for instance, or the “model government agency.”

We are moving toward organic design, informed by mission, purpose, strategy, and the environment, both social and physical—the design I began to advocate forty years ago in The Practice of Management (which came out in 1954). …

Sidebar: … to pursue the preceding line of thought

see Management’s New Paradigm

… the center of a modern society, economy and community is not technology.

It is not information.

It is not productivity.

The center of modern society is the managed institution.

The managed institution is society’s way of getting things done these days.

And management is the specific tool, the specific function, the specific instrument, to make institutions capable of producing results.

The institution, in short, does not simply exist within and react to society.

It exists to produce results on and in society.

… and Management, Revised Edition which contains a similarly named chapter with a different “landscape” a.k.a. “brainscape.”

Management Cases (Revised Edition) provides a more day-to-day, issue-to-issue, situational “landscape” view.

Also “From Analysis to Perception — The New World View” found in The New Realities or The Essential Drucker.

Form and Function Connections: see chapters On Being the Right Size and On Being the Wrong Size in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices and others. (calendarize this?)

Creativity from Chapter 10 of Management, Revised Edition

Try a MRE page search for the word stem “creat”

To make the future happen one need not, in other words, have a creative imagination.

It requires work rather than genius—and therefore is accessible in some measure to everybody.

The man of creative imagination will have more imaginative ideas, to be sure.

But that the more imaginative idea will actually be more successful is by no means certain.

Pedestrian ideas have at times been successful;

Bata’s idea of applying American methods to making shoes was not very original in the Europe of 1920, with its tremendous interest in Ford and his assembly line.

What mattered was his courage rather than his genius.

To make the future happen one has to be willing to do something new.

One has to be willing to ask,

“What do we really want to see happen that is quite different from today?”

One has to be willing to say,

“This is the right thing to happen as the future of the business.

We will work on making it happen.”

Lack of “creativity,” which looms so large in present discussions of innovation, is not the real problem.

There are more ideas in any organization, including businesses, than can possibly be put to use.

What is lacking, as a rule, is the willingness to look beyond products to ideas.

[See Sur/petition]

Products and processes are only the vehicle through which an idea becomes effective.

See piloting and strategies

Dense reading and Dense listening and Thinking broad and Thinking detailed

And, as the illustrations should have shown, the specific future products and processes can usually not even be imagined.

When DuPont started the work on polymer chemistry out of which nylon eventually evolved, it did not know that man-made fibers would be the end product.

DuPont acted on the assumption that any gain in man’s ability to manipulate the structure of large, organic molecules—at that time in its infancy—would lead to commercially important results of some kind.

Only after six or seven years of research work did man-made fibers first appear as a possible major result area.

Moreover, the manager often lacks the courage to commit resources to such an idea.

The resources that should be invested in making the future happen should be small, but they must be of the best.

Otherwise nothing happens.

However, the greatest lack of the manager is a touchstone of validity and practicality.

An idea has to meet rigorous tests if it is to be capable of making the future of a business.

It has to have operational validity.

Can we take action on this idea?

Or can we only talk about it?

Can we really do something right away to bring about the kind of future we want to make happen?

To be able to spend money on research is not enough.

It must be research directed toward the realization of the idea.

The knowledge sought may be general, as was that of DuPont’s project.

But it must at least be reasonably clear that if available, it would be applicable knowledge.

The idea must also have economic validity.

If it could be put to work right away in practice, it should be able to produce economic results.

We may not be able to do what we would like to for a long time, perhaps never.

But if we could do it now, the resulting products, processes, or services would find a customer, a market, an end-use; should be capable of being sold profitably; should satisfy a want and a need.

The idea itself might aim at social reform.

But unless an organization can be built on it, it is not a valid entrepreneurial idea.

The test of the idea is not the votes it gets or the acclaim of the philosophers.

It is economic performance and economic results.

Even if the rationale of the business is social reform rather than business success, the touchstone must be the ability to perform and to survive as a business.

Finally, the idea must meet the test of personal commitment.

Do we really believe in the idea?

Do we really want to be that kind of people, do that kind of work, run that kind of business?

To make the future demands courage.

It demands work.

But it also demands faith.

To commit ourselves to the expedient is simply not practical.

It will not suffice for the tests ahead.

For no such idea is foolproof—nor should it be.

The one idea regarding the future that must inevitably fail is the apparently “sure thing,” the “riskless idea,” the one “that cannot fail.”

The idea on which tomorrow’s business is to be built must be uncertain; no one can really say as yet what it will look like if and when it becomes reality.

It must be risky:

it has a probability of success but also of failure.

If it is not both uncertain and risky, it is simply not a practical idea for the future.

For the future itself is both uncertain and risky.

Unless there is personal commitment to the values of the idea and faith in them, the necessary efforts will therefore not be sustained.

The manager should not become an enthusiast, let alone a fanatic.

She should realize that things do not happen just because she wants them to happen—not even if she works very hard at making them happen.

Like any other effort, the work on making the future happen should be reviewed periodically to see whether continuation can still be justified both by the results of the work to date and by the prospects ahead.

Ideas regarding the future can become investments in managerial ego too, and need to be carefully tested for their capacity to perform and to give results.

But the people who work on making the future also need to be able to say with conviction, “This is what we really want our business to be.”

It is perhaps not absolutely necessary for every organization to search for the idea that will make the future.

A good many organizations and their managements do not even make their present organizations effective—and yet the organizations somehow survive for a while.

The big business, in particular, seems to be able to coast a long time on the courage, work, and vision of earlier managers.

But tomorrow always arrives.

It is always different.

And then even the mightiest company is in trouble if it has not worked on the future.

It will have lost distinction and leadership—all that will remain is big-company overhead.

It will neither control nor understand what is happening.

Not having dared to take the risk of making the new happen, it perforce took the much greater risk of being surprised by what did happen.

And this is a risk that even the largest and richest organization cannot afford and that even the smallest one need not run.

To be more than a slothful steward of the talents in one’s keeping, the manager has to accept responsibility for making the future happen.

It is the willingness to tackle this purposefully that distinguishes the great organization from the merely competent one, and the organization builder from the manager-suite custodian.

A scorecard for managers A scorecard for managers

Company performance: five telltale tests Company performance: five telltale tests

Without an effective mission statement, there will be no performance Without an effective mission statement, there will be no performance

Continuity and change Continuity and change

Look Look

Management Challenges for the 21st Century Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Making the future Making the future

Managing in the Next Society Managing in the Next Society

DESPITE its crucial importance, its high visibility and its spectacular rise, management is the least known and the least understood of our basic institutions.

Even the people in a business often do not know what their management does and what it is supposed to be doing, how it acts and why, whether it does a good job or not.

Indeed, the typical picture of what goes on in the “front office” or on “the fourteenth floor” in the minds of otherwise sane, well-informed and intelligent employees (including, often, people themselves in responsible managerial and specialist positions) bears striking resemblance to the medieval geographer’s picture of Africa as the stamping ground of the one-eyed ogre, the two-headed pygmy, the immortal phoenix and the elusive unicorn.

What then is management: What does it do?

The Practice of Management

A lot of people are confused by the word management.

Many assume or think that being given the title of manager instantly makes one a manager.

If that were the case how do we distinguish between those who actually manage and those who just have the title?

Also how do we differentiate between those in healthy, well performing institutions and sick institutions?

Despite all the outpouring of management writing these last twenty-five years, the world of management is still little-explored.

It is a world of issues, but also a world of people.

And it is undergoing rapid change right now.

These essays explore a wide variety of topics.

They deal with changes in the work force, its jobs, its expectations, with the power relationships of a “society of employees,” and with changes in technology and in the world economy.

They discuss the problems and challenges facing major institutions, including business enterprises, schools, hospitals, and government agencies.

They look anew at the tasks and work of executives, at their performance and its measurement and at executive compensation.

However diverse the topics, all the pieces reflect upon the same reality: In all developed countries the workaday world has become a “society of organizations” and thus dependent on executives, that is on people—whether called managers or administrators—who are paid to direct organizations and to make them perform.

These chapters have one common theme: the changing world of the executive —

changing rapidly within the organization;

changing rapidly in respect to the visions, aspirations, and even characteristics of employees, customers, and constituents;

changing outside the organization as well—economically, technologically, socially, politically.

The Changing World of The Executive

The Future of Top Management

Amazon Link: Managing in the Next Society

As the corporation moves toward a confederation or a syndicate, it will increasingly need a top management that is separate, powerful, and accountable.

This top management’s responsibilities will cover the entire organization’s

direction, planning, strategy, values, and principles;

its structure and its relationship between its various members;

its alliances, partnerships, and joint ventures; and its research, design, and innovation.

It will have to take charge of the management of the two resources common to all units of the organization: key people and money.

It will represent the corporation to the outside world and maintain relationships with governments, the public, the media, and organized labor.

Life at the Top

An equally important task for top management in the Next Society’s corporation will be to balance the three dimensions of the corporation: as an economic organization, as a human organization, and as an increasingly important social organization.

Each of the three models of the corporation developed in the past half-century stressed one of these dimensions and subordinated the other two.

The German model of the “social market economy” put the emphasis on the social dimension, the Japanese one on the human dimension, and the American one (“shareholder sovereignty”) on the economic dimension.

None of the three is adequate on its own.

The German model achieved both economic success and social stability, but at the price of high unemployment and dangerous labor-market rigidity.

The Japanese model was strikingly successful for twenty years, but faltered at the first serious challenge; indeed it has become a major obstacle to recovery from Japan’s present recession.

Shareholder sovereignty is also bound to flounder.

It is a fair-weather model that works well only in times of prosperity.

Obviously the enterprise can fulfill its human and social functions only if it prospers as a business.

But now that knowledge workers are becoming the key employees, a company also needs to be a desirable employer to be successful.

Paradoxically, the claim to the absolute primacy of business gains that made shareholder sovereignty possible has also highlighted the importance of the corporation’s social function.

The new shareholders whose emergence since 1960 or 1970 produced shareholder sovereignty are not “capitalists.”

They are employees who own a stake in the business through their retirement and pension funds.

By 2000, pension funds and mutual funds had come to own the majority of the share capital of America’s large companies.

This has given shareholders the power to demand short-term rewards.

But the need for a secure retirement income will increasingly focus on people’s minds on the future value of the investment.

Corporations, therefore, will have to pay attention both to their short-term business results and to their long-term performance as providers of retirement benefits.

The two are not irreconcilable, but they are different, and they will have to be balanced.

Over the past decade or two, managing a large corporation has changed out of all recognition.

That explains the emergence of the “CEO superman,” such as Jack Welch of GE, Andrew Grove of Intel, or Sanford Weill of Citigroup.

But organizations cannot rely on supermen to run them; the supply is both unpredictable and far too limited.

Organizations survive only if they can be run by competent people who take their job seriously.

That it takes genius today to be the boss of a big organization clearly indicates that top management is in crisis.

Impossible Jobs

The recent failure rate of chief executives in big American companies points in the same direction.

A large proportion of CEOs of such companies appointed in the past ten years were fired as failures within a year or two.

But each of these people had been picked for his proven competence, and each had been highly successful in his previous jobs.

This suggests that the jobs they took on had become un-doable.

The American record suggests not human failure but systems failure.

Top management in big organizations needs a new concept.

Some elements of such a concept are beginning to emerge.

For instance, Jack Welch at GE has built a top-management team in which the company’s chief financial officer and its chief human resources officer are near equals to the chief executive and are both excluded from the succession to the top job.

He has also given himself and his team a clear and publicly announced priority task on which to concentrate.

During his twenty years in the top job, Mr. Welch has had three such priorities, each occupying him for five years or more.

Each time he has delegated everything else to the top managements of the operating businesses within the GE confederation.

A different approach has been taken by Asea Brown Boveri (ABB), a huge Swedish-Swiss engineering multinational.

Goran Lindahl, who retired as chief executive earlier this year, went even further than GE in making the individual units within the company into separate worldwide businesses and building up a strong top-management team of a few nonoperating people.

But he also defined for himself a new role as a one-man information system for the company, traveling incessantly to get to know all the senior managers personally, listening to them and telling them what went on within the organization.

A largish financial services company tried another idea: appointing not one CEO but six.

The head of each of the five operating businesses is also CEO for the whole company in one top-management area, such as corporate planning and strategy or human resources.

The company’s chairman represents the company to the outside world and is also directly concerned with obtaining, allocating, and managing capital.

All six people meet twice a week as the top management committee.

This seems to work well, but only because none of the five operating CEOs wants the chairman’s job; each prefers to stay in operations.

Even the man who designed the system, and then himself took the chairman’s job, doubts that the system will survive once he is gone.

In their different ways, the top people at all of these companies were trying to do the same thing: to establish their organization’s unique personality.

And that may well be the most important task for top management in the Next Society’s big organizations.

In the half-century after the Second World War, the business corporation has brilliantly proved itself as an economic organization, i. e., a creator of wealth and jobs.

In the Next Society, the biggest challenge for the large company—especially for the multinational—may be its social legitimacy: its values, its mission, its vision.

Increasingly, in the Next Society’s corporation, top management will, in fact, be the company.

Everything else can be outsourced.

Will the corporation survive?

Yes, after a fashion.

Something akin to a corporation will have to coordinate the Next Society’s economic resources.

Legally and perhaps financially, it may even look much the same as to day’s corporation.

But instead of there being a single model adopted by everyone, there will be a range of models to choose from.

And there equally will be a number of top-management models to choose from.

This might be a good stopping point

for a first read

Management is a (the) most special concept—a most special positive concept.

In essence it is not a bunch of techniques, tips, or tricks layered on current organizations.

Does the idea of bad management decisions make sense?

How could it be management and be bad?

Does the assertion that someone managed to bankrupt an organization seem right?

What could we call the steering mechanism that led to the bankruptcy?

We can think of management, mis-management, and non-management.

The term mis-management is still troubling.

Maybe it should be replaced with organizational suicide or severe injury.

What about all the people claiming to be management consultants and pushing management fads?

Background: The organizational experience that exists in society (starting around the late 1800s) is predominately “product” or “service driven"—inside-out thinking.

Somebody has an idea that they sell—hard.

The attempt is to convince the outside world that their lives are going to be better from this product or service.

(At one point in our not too distant history this was selling into a vacuum which has subsequently been filled—actually overfilled).

Improvements in this idea may be attempted.

Competition sets in.

There’s a shake-out.

Facilities are closed.

Jobs and money are lost.

At some point the product or service becomes obsolete.

During these phases the “do more, better” mentality may set in.

When this product/service approach is examined at a point in time—1920, 1950, etc.—the vulnerability of product/service driven organizations is obvious.

Do we consumers really want to trade our lives for just a better version of yesterday’s product’s and services.

In all this where is the outside-in thinking?

All of these inside-out organizations have people with the title of manager, but having a title doesn’t make one a manager.

Also being a most excellent manager at one point in time doesn’t necessarily make one a manager forever—it constantly has to be re-earned.

Many people will point to financial results as proof of management performance.

However examining the current track record of a 1960s, 1970s, or 1980s list of organizations with great track records reveals the flaw in the financial results reasoning.

Many people think management is primarily about controlling subordinates in a “business.”

Examining the table of contents of Peter Drucker’s Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices and Management, Revised Edition reveals a much broader scope.

It would be possible to calculate a ratio of any specific topic to the total management radar scope.

An updated scope could be developed by exploring his total writings.

Many people have the notion that overall performance is the sum of the performances of the parts of an organization.

Does a group of excellent performing musicians equal an orchestra with a reputation for excellence?

What if few people want to hear this orchestra or what they play?

The following quotes can be found in Management, Revised Edition and Post-Capitalist Society by Peter Drucker

Rarely in human history has any institution emerged as quickly as management or had as great an impact so fast.

In less than 150 years, management has transformed the social and economic fabric of the world’s developed countries.

It has created a global economy and set new rules for countries that would participate in that economy as equals.

And it has itself been transformed.

Few executives are aware of the tremendous impact management has had.

Indeed, a good many are like M. Jourdain, the character in Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, the Molière play, who did not know that he spoke prose.

They barely realize that they practice—or mispractice—management.

As a result, they are ill-prepared for the tremendous challenges that now confront them.

The truly important problems managers face do not come from technology or politics.

They do not originate outside management and enterprise.

They are problems caused by the very success of management itself.

To be sure, the fundamental task of management remains the same: to make people capable of joint performance through common goals, common values, the right structure, and the training and development they need to perform and to respond to change.

But the very meaning of this task has changed, if only because the performance of management has converted the workforce from one composed largely of unskilled laborers to one of highly educated knowledge workers.

What Is Management? (take 2)

Management may be the most important innovation of the twentieth century and the one most directly affecting the young, educated people in colleges and universities who will be tomorrow’s “knowledge workers” in managed institutions, and their managers the day after tomorrow.

But what is management?

Why management?

How do you define “managers"?

What are their tasks, their responsibilities?

And how has the study and discipline of management developed to its present state?

Within the life span of today’s old-timers, our society has become a knowledge society, a society of organizations, and a network society.

In the twentieth century, the major social tasks came to be performed in and through organized institutions—business enterprises, large and small; school systems; colleges and universities; hospitals; research laboratories; governments and government agencies of all kinds and sizes; and many others.

And each of them in turn is entrusted to “managers” who practice “management.”

Without the institution, there would be no management.

But without management, there would be only a mob rather than an institution.

The institution is itself an organ of society and exists only to contribute a needed result to society, the economy, and the individual.

Organs, however, are never defined by what they do, let alone by how they do it.

They are defined by their contribution.

And it is management that enables the institution to contribute.

Management is tasks.

Management is a discipline.

But management is also people.

Every achievement of management is the achievement of a manager.

Every failure is a failure of a manager.

People manage rather than “forces” or “facts.”

The vision, dedication, and integrity of managers determine whether there is management or mismanagement.

Management and managers are the specific need of all institutions, from the smallest to the largest.

They are the specific organ of every institution.

They are what holds it together and makes it work.

None of our institutions could function without managers.

And managers do their own job—they do not do it by delegation from the owner.”

The need for management does not arise just because the job has become too big for any one person to do alone.

Managing a business enterprise or a public-service institution is inherently different from managing one's own property or from running a practice of medicine or a solo law or consulting practice.

Of course, many a large and complex enterprise started from a one-man shop. (think organization evolution)

But beyond the first steps, growth soon entails more than a change in size.

At some point (and long before the organization becomes even “fair-sized”), size turns into complexity.

At this point “owners” no longer run “their own” businesses even if they are the sole proprietors.

They are then in charge of a business enterprise—and if they do not rapidly become managers, they will soon cease to be “owners” and be replaced, or the business will go under and disappear.

For at this point, the business turns into an organization and requires for its survival different structure, different principles, different behavior, and different work.

It requires managers and management.

Legally, management in the business enterprise is still seen as a delegation of ownership.

But the doctrine that already determines practice, even though it is still only evolving in law, is that management precedes and even outranks ownership.

The owner has to subordinate himself to the enterprise’s need for management and managers.

There are, of course, many owners who successfully combine both roles, that of owner-investor and that of top management.

But if the enterprise does not have the management it needs, ownership itself is worthless.

And in enterprises that are big or that play such a crucial role as to make their survival and performance matters of national concern, public pressure or governmental action will take control away from an owner who stands in the way of management.

Thus the late Howard Hughes was forced by the United States government in the 1950s to give up control of his wholly owned Hughes Aircraft Company, which produced electronics crucial to U.S. defense.

Managers were brought in because he insisted on running the company as “owner.”

Similarly the German government in the 1960s put the faltering Krupp company under autonomous management, even though the Krupp family owned 100 percent of the stock.

The change from a business that the owner-entrepreneur can run with “helpers” to a business that requires management is a sweeping change.

It requires the application of basic concepts, basic principles, and individual vision to the enterprise.

One can compare the two kinds of business to two different kinds of organism: the insect, which is held together by a tough, hard skin, and the vertebrate animal, which has a skeleton.

Land animals that are supported by a hard skin cannot grow beyond a few inches in size.

To be larger, animals must have a skeleton.

Yet the skeleton has not evolved out of the hard skin of the insect; for it is a different organ with different antecedents.

Similarly, management becomes necessary when an organization reaches a certain size and complexity.

But management, while it replaces the “hard-skin” structure of the owner-entrepreneur, is not its successor.

It is, rather, its replacement.

When does a business reach the stage at which it has to shift from “hard skin” to “skeleton"?

The line lies somewhere between 300 and 1,000 employees in size.

More important, perhaps, is the increase in complexity.

When a variety of tasks all have to be performed in cooperation, synchronization, and communication, an organization needs managers and management.

One example would be a small research lab in which twenty to twenty-five scientists from a number of disciplines work together.

Without management, things go out of control.

Plans fail to turn into action.

Or worse, different parts of the plans get going at different speeds, different times, and with different objectives and goals.

The favor of the “boss” becomes more important than performance.

At this point the product may be excellent, the people able and dedicated.

The boss may be—and often is—a person of great ability and personal power.

But the enterprise will begin to flounder, stagnate, and soon go downhill unless it shifts to the “skeleton” of managers and management structure. (calendarize this?)

The word “management” is centuries old.

Its application to the governing organ of an institution and particularly to a business enterprise is American in origin.

“Management” denotes both a function and the people who discharge it.

It denotes a social position and authority, but also a discipline and a field of study.

Even in American usage, “management” is not an easy term, for institutions other than business do not always speak of management or managers.

Universities or government agencies have administrators, as have hospitals.

Armed services have commanders.

Other institutions speak of executives, and so on.

Yet all these institutions have in common the management function, the management task, and the management work.

All of them require management.

And in all of them, management is the effective, the active organ.

Management As The Agent Of Transformation

On the threshold of World War I, a few thinkers were just becoming aware of management’s existence.

But few people, even in the most advanced countries, had anything to do with “management.”

Now the largest single group in the labor force, more than one-third of the total, are people whom the U.S. Bureau of the Census calls “managerial and professional.”

Management has been the main agent of this transformation.

Management explains why, for the first time in human history, we can employ large numbers of knowledgeable, skilled people in productive work.

No earlier society could do this.

Indeed, no earlier society could support more than a handful of such people.

Until quite recently, no one knew how to put people with different skills and knowledge together to achieve common goals.

Eighteenth-century China was the envy of contemporary Western intellectuals because it supplied more jobs for educated people than did all of Europe—some 20,000 per year.

Today the United States, with about the same population China then had, graduates more than one million college students a year, few of whom have the slightest difficulty finding well-paid employment.

Management enables us to employ them.

Knowledge, especially advanced knowledge, is always specialized.

By itself it produces nothing.

Yet a modern business, and not only the largest ones, may employ up to 10,000 highly knowledgeable people who represent up to sixty different knowledge areas.

Engineers of all sorts, designers, marketing experts, economists, statisticians, psychologists, planners, accountants, human resources people—all working together in a joint venture.

None would be effective without the managed enterprise.

After World War II we began to see that management is not business management.

It pertains to every human effort that brings together in one organization people of diverse knowledge and skills.

It needs to be applied to all social sector institutions, such as hospitals, universities, churches, arts organizations, and social-service agencies, which since World War II have grown faster in the United States than either business or government.

For even though the need to manage volunteers or raise funds may differentiate nonprofit managers from their for-profit peers, many more of their responsibilities are the same—among them defining the right strategy and goals, developing people, measuring performance, and marketing the organization’s services.

Management, world-wide, has become the new social function.

There is no point in asking which came first: the educational explosion of the last hundred years or the management that put this knowledge to productive use.

Modern management and modern enterprise could not exist without the knowledge base that developed societies have built.

But equally it is management, and management alone, that makes effective all this knowledge and these knowledgeable people.

The emergence of management has converted knowledge from social ornament and luxury into the true capital of any economy.

Management And Entrepreneurship

One important advance in the discipline and in the practice of management is that both now embrace entrepreneurship and innovation.

A sham fight these days pits “management” against “entrepreneurship” as adversaries, if not as mutually exclusive. That’s like saying that the fingering hand and the bow hand of the violinist are “adversaries” or “mutually exclusive.”

Both are always needed and at the same time.

And both have to be coordinated and work together.

Any existing organization, whether a business, a church, a labor union, or a hospital, goes down fast if it does not innovate.

Conversely, any new organization, whether a business, a church, a labor union, or a hospital, collapses if it does not manage.

Not to innovate is the single largest reason for the decline of existing organizations.

Not to know how to manage is the single largest reason for the failure of new ventures.

See Innovation and Entrepreneurship (the book) and Entrepreneurs and Innovation (the article).

Innovation creates new wealth or new potential of action rather than new knowledge.

This means that the bulk of innovative efforts will have to come from the places that control the manpower and the money needed for development and marketing, that is, from the existing large aggregation of trained manpower and disposable money—existing businesses and existing public-service institutions.

The Dimensions of Management

There are three basic tasks—they might be called dimensions—in management.

There is the first task of thinking through and defining the specific purpose and mission of the organization—whether business enterprise, hospital, school, or government agency.

There is the second task of making work productive and the worker achieving.

There is finally the task of managing social impacts and social responsibilities.

In respect to the second and third tasks, all institutions are alike.

It is the first task that distinguishes the business from the hospital, school, or government agency.

And the specific purpose and mission of business enterprise is economic performance.

To discharge it, managers always have to balance the present against an uncertain and risky future, have to perform for the short run and make their business capable of performance over the long run.

Managers always have to be stewards of what already exists; they have to be administrators.

They also have to create what is to be; they have to be entrepreneurs, risk takers, and innovators.

For a modern business can produce results, both for society and for its own people, only if it can survive beyond the life span of a person and perform in a new and different future

Mission

An institution exists for a specific purpose and mission, a specific social function.

In the business enterprise, this means economic performance.

With respect to this first task, the task of specific performance, business and nonbusiness institutions differ.

In respect to every other task, they are similar.

But only business has economic performance as its specific mission.

It is the definition of a business that it exists for the sake of economic performance.

In all other institutions—hospital, church, university, or armed services—economics is a restraint.

In those institutions, the budget sets limits to what the institution and the manager can do.

In business enterprise, economic performance is the rationale and purpose.

Business management must always, in every decision and action, put economic performance first.

It can justify its existence and its authority only by the economic results it produces.

A business management has failed if it fails to produce economic results.

It has failed if it does not supply goods and services desired by the consumer at a price the consumer is willing to pay.

It has failed if it does not improve, or at least maintain, the wealth-producing capacity of the economic resources entrusted to it.

And this, whatever the economic or political structure or ideology of a society, means responsibility for profitability.

But business management is no different from the management of other institutions in one crucial respect: it has to manage.

And managing is not just passive, adaptive behavior; it means taking action to make the desired results come to pass.

The early economist conceived of the businessman’s behavior as purely passive; success in business meant rapid and intelligent adaptation to events occurring outside, in an economy shaped by impersonal, objective forces that were neither controlled by the businessman nor influenced by his reaction to them.

We may call this the concept of the “trader.”

Even if he was not considered a parasite, his contributions were seen as purely mechanical: the shifting of resources to more productive use.

Today’s economist sees the businessman as choosing rationally between alternatives of action.

This is no longer a mechanistic concept; obviously the choice has a real impact on the economy.

But still, the economist’s “businessman”—the picture that underlies the prevailing economic “theory of the firm” and the theorem of the “maximization of profits”—reacts to economic developments.

The businessperson is still passive, still adaptive—though with a choice among various ways to adapt.

Basically, this is a concept of the “investor” or the “financier” rather than of the manager.

Of course, it is always important to adapt to economic changes rapidly, intelligently, and rationally.

But managing implies responsibility

for attempting to shape the economic environment;

for planning, initiating, and carrying through changes in that economic environment;

for constantly pushing back the limitations of economic circumstances on the enterprise’s ability to contribute.

What is possible—the economist’s “economic conditions”—is therefore only one pole in managing a business.

What is desirable in the interest of economy and enterprise is the other.

And while humanity can never really “master” the environment, while we are always held within a tight vise of possibilities, it is management’s specific job to make what is desirable first possible and then actual.

Management is not just a creature of the economy; it is a creator as well.

And only to the extent to which it masters the economic circumstances, and alters them by consciously directed action, does it really manage.

To manage a business means, therefore, to manage by objectives

Chapter 3, Management, Revised Edition

Organization As A Distinct Species