Knowledge: Its Economics and Its Productivity

From chapter 10 of Post-Capitalist Society

Also see chapter 4 “The Productivity of the New Work Forces”

by Peter Drucker (a social ecologist)

(calendarize this?)

Amazon link: Post-Capitalist Society

(portions omitted)

… AT FIRST GLANCE, the economy appears hardly to have been affected by the shift to knowledge as the basic resource.

It seems to have remained “capitalist” rather than “post-capitalist.”

But looks are deceptive.

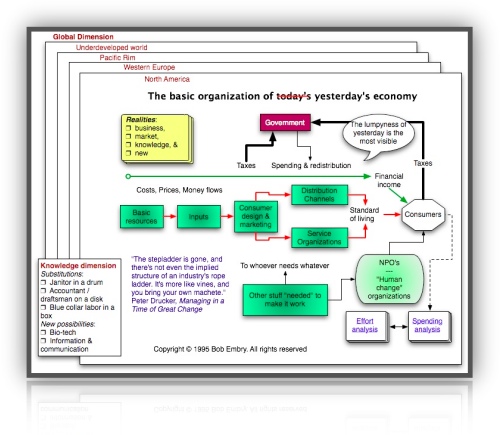

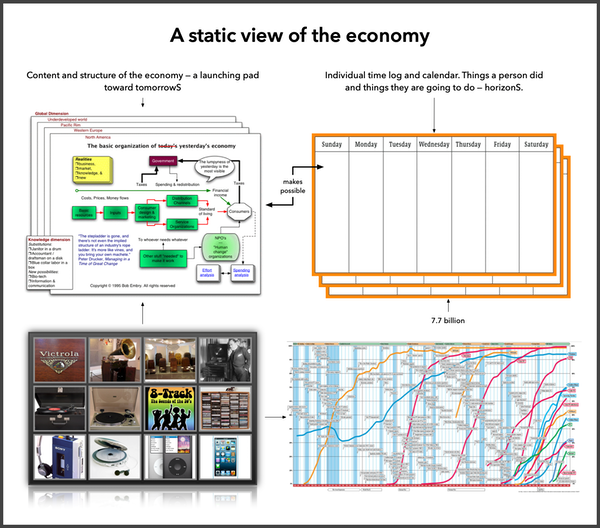

Elements of economic content

Economic content and structure landscape

«§§§»

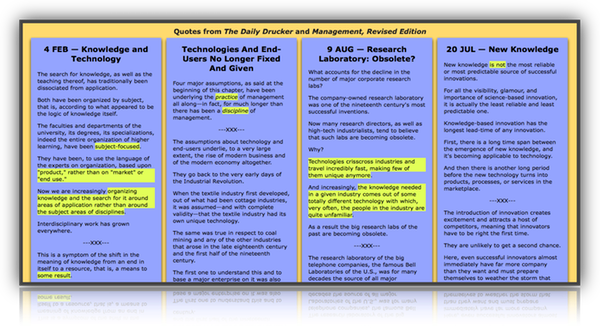

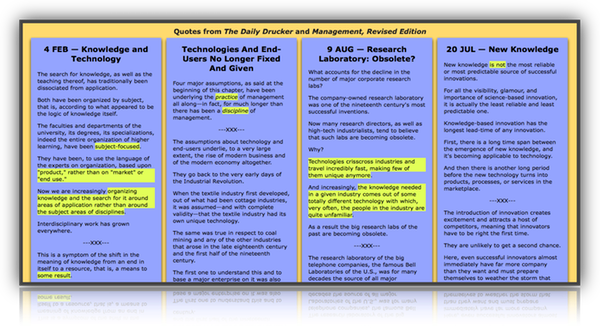

Knowledge and technology

Larger

… snip, snip …

The economy will, to be sure, remain a market economy and a worldwide one.

It will reach even further than did the world market economy before World War I, when there were no “planned” economies and no “Socialist” countries.

…

Increasingly, there is less and less return on the traditional resources: labor, land and (money) capital.

The main producers of wealth have become information and knowledge.

THE ECONOMICS OF KNOWLEDGE

How knowledge behaves as an economic resource, we do not yet fully understand; we have not had enough experience to formulate a theory and to test it.

…

We can only say so far that we need such a theory.

We need an economic theory that puts knowledge into the center of the wealth-producing process.

When it comes to new knowledge, there are three kinds (as already discussed in Chapter 4 above).

Larger

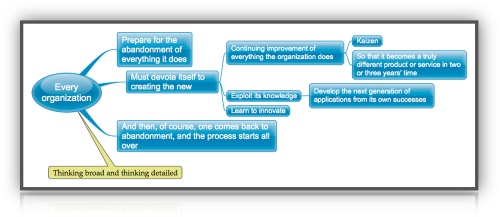

There is first the continuing improvement of process, product, service; the Japanese, who do it best, call this Kaizen.

Then there is exploitation: the continuous exploitation of existing knowledge (from where ever it exists) to develop new and different products, processes, and services.

Finally, there is genuine innovation.

These three ways of applying knowledge to produce change in the economy (and in society as well) need to be worked at together and at the same time.

They are all equally necessary.

But their economic characteristics—their costs as well as their economic impacts—are qualitatively different.

…

So far, at least, it is not possible to quantify knowledge.

We can, of course, estimate how much it costs to produce and distribute knowledge.

But how much is produced — indeed, what we might even mean by “return on knowledge” — we cannot say.

…

Yet we can have no economic theory unless there is a model that expresses economic events in quantitative relationships.

Without it, there is no way to make a rational choice—and rational choices are what economics is all about.

…

Above all, the amount of knowledge, that is, its quantitative aspect, is not nearly as important as the productivity of knowledge, that is, its qualitative impact.

And this applies to old knowledge and its application, as well as to new knowledge.

THE PRODUCTIVITY OF KNOWLEDGE

Knowledge does not come cheap.

All developed countries spend something like a fifth of their GNP on the production and dissemination of knowledge.

…

Knowledge formation is thus already the largest investment in every developed country.

…

Surely, the return which a country or a company gets on knowledge must increasingly be a determining factor in its competitiveness.

…

Increasingly, productivity of knowledge will be decisive in its economic and social success, and in its entire economic performance.

And we know that there are tremendous differences in the productivity of knowledge between countries, between industries, between individual organizations.

Here are a few examples:

…

It is likely that the productivity of resources will altogether become a central concern of economics in the post-capitalist society.

It underlies the relationship between environment and economic growth.

…

That this new concern will lead to very different economies is one of the consequences of our recent work on the productivity of money

…

They showed that under central planning, additional units of capital investment yield less and less additional output.

…

Innovation that is, the application of knowledge to produce new knowledge, is not, as so much American folklore asserts, “inspiration” and best done by loners in their garages.

It requires systematic effort, and a high degree of organization.

See my 1986 book Innovation and Entrepreneurship (New York: Harper & Raw; London: Wm. Heinemann)

But it also requires both decentralization and diversity, that is, the opposite of central planning and centralization.

THE MANAGEMENT REQUIREMENTS

“Centralization,” “decentralization,” and “diversity” are not terms of economics.

They are management terms.

…

We do not have an economic theory of the productivity of knowledge investment; we may never have one.

But we have management precepts.

See Management and Economic Development

management and Management, Revised Edition

We know above all that making knowledge productive is a management responsibility.

It cannot be discharged by government; but it also cannot be done by market forces.

It requires systematic, organized application of knowledge to knowledge.

The first rule may well be that knowledge has to aim high to produce results.

The steps may be small and incremental but the goal must be ambitious.

Knowledge is productive only if it is applied to make a difference.

The Hungarian-American Nobel prizewinner Albert Szent-Györgyi (1893-1990) revolutionized physiology.

When asked to explain his achievements, he gave the credit to his teacher, an otherwise obscure professor at a provincial Hungarian university.

“When I got my doctorate,” Szent-Györgyi said, “I proposed to study flatulence—nothing was known about it and nothing is known about it still.”

“Very interesting,” the professor said, “but no one has ever died of flatulence.

If you have results (and it’s a big ‘if’), you’d better have them where they’ll make a difference.”

“And so,” Szent-Györgyi went on, “I took up the study of basic bodily chemistry and discovered the enzymes.”

Every single one of Szent-Györgyi’s research projects was a small step.

But from the beginning he aimed high: discovery of the basic chemistry of the human body.

Similarly, in Japanese Kaizen, every single step is a small one — a minor change here, a minor improvement there.

But the aim is to produce by means of step-by-step improvements a radically different product, process, or service a few years later.

The aim is to make a difference.

To make knowledge productive further requires that it be clearly focused.

It has to be highly concentrated.

Whether done by an individual or by a team, the knowledge effort requires purpose and organization.

It is not “flash of genius.”

It is hard work.

To make knowledge productive also requires the systematic exploitation of opportunities for change what in an earlier book I called the “Seven Windows of Innovation.”

See Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

These opportunities have to be matched with the competencies and strengths of the knowledge worker and the knowledge team.

To make knowledge productive finally requires managing time.

High knowledge productivity — whether in improvement, in exploitation, or in innovation — comes at the end of a long gestation period.

Yet productivity of knowledge also requires a constant stream of short-term results.

It thus requires the most difficult of all management achievements: balancing the long term with the short term.

Our experience in making knowledge productive has so far been gained mainly in the economy and technology.

But the same rules pertain to making knowledge productive in society, in the polity, and with respect to knowledge itself.

So far, little work has been done to apply knowledge to these areas.

But we need productivity of knowledge even more in these areas than we need it in the economy, in technology, or in medicine.

ONLY CONNECT

The productivity of knowledge requires increasing the yield from what is known—whether by the individual or by the group.

There is an old American story of the farmer who turns down a proposal for a more productive farming method by saying, “I already know how to farm twice as well as I do.”

Most of us (perhaps all of us) know many times more than we put to use.

The main reason is that we do not mobilize the multiple knowledges we possess.

We do not use knowledges as part of one toolbox.

Instead of asking: “What do I know, what have I learned, that might apply to this task?” we tend to classify tasks in terms of specialized knowledge areas.

What needs doing? Here and here

Again and again in working with executives I find that a given challenge in organizational structure, for instance, or in technology yields to knowledge the executives already possess: They may have acquired it, for instance, in an economics course at the university.”

Of course, I know that,” is the standard response, “but it’s economics, not management.”

This is a purely arbitrary distinction—necessary perhaps to learn and to teach a “subject,” but irrelevant as a definition of what knowledge is and what it can do.

larger composite view ↑ ::: Economic & content and structure ::: Adoption rates: one & two

From knowledge to knowledges

Knowledge exists only in application

Knowledge and technology

The way we traditionally arrange our businesses, government agencies, and universities further encourages the tendency to believe that the purpose of the tools is to adorn the toolbox rather than to do work.

Peter Drucker: Social Ecologist

In learning and teaching, we do have to focus on the tool.

In usage, we have to focus on the end result, on the task, on the work.

“Only connect” was the constant admonition of a great English novelist, E.M. Forster.

It has always been the hallmark of the artist, but equally of the great scientist — of a Darwin, a Bohr, an Einstein.

At their level, the capacity to connect may be inborn and part of that mystery we call “genius.”

But to a large extent, the ability to connect and thus to raise the yield of existing knowledge (whether for an individual, for a team, or for the entire organization) is learnable.

Eventually, it should become teachable.

Knowledge and Research management

Knowledge economy and knowledge polity

It requires a methodology for problem definition—even more urgently perhaps than it requires the currently fashionable methodology for “problem solving.”

It requires systematic analysis of the kind of knowledge and information a given problem requires, and

a methodology for organizing the stages in which a given problem can be tackled—the methodology which underlies what we now call “systems research.”

It requires what might be called “Organizing Ignorance” (The title of a book I began to write forty years ago but never finished.) —

and there is always so much more ignorance around than there is knowledge.

Do alliances etc. have a role to play?

Specialization into knowledges has given us enormous performance potential in each area.

But because knowledges are so specialized, we need also a methodology, a discipline, a process to turn this potential into performance.

Thinking broad and thinking detailed

How To Guarantee Non-Performance

Attention-directing

TO-LO-PO-SO-GO

Research management

Otherwise, most of the available knowledge will not become productive; it will remain mere information.

Larger

Not to see the forest for the trees is a serious failing.

But it is an equally serious failing not to see the trees for the forest.

One can only plant and cut down individual trees.

Yet the forest is the “ecology,” the environment without which individual trees would never grow.

To make knowledge productive, we will have to learn to see both forest and tree.

We will have to learn to connect.

The productivity of knowledge is going to be the determining factor in the competitive position of a company, an industry, an entire country.

No country, industry, or company has any “natural” advantage or disadvantage.

The only advantage it can possess is the ability to exploit universally available knowledge.

The only thing that increasingly will matter in national as in international economics is management’s performance in making knowledge productive.

see Management, Revised Edition

There are major structural implications—bobembry (site creator).

Find “connect” in Drucker on Asia — A Dialogue Between Peter Drucker and Isao Nakauchi

Extrapolate the changing content and structure of the economy out thirty years and then re-apply the above … repeat. What does this mean for the education system?

What are you going to calendarize from this page?

More connections

Luther, Machiavelli, and the Salmon Luther, Machiavelli, and the Salmon

From Analysis to Perception — the New Worldview From Analysis to Perception — the New Worldview

The Educated Person The Educated Person

Knowledge system view Knowledge system view

Knowledge Knowledge

Knowledge worker productivity Knowledge worker productivity

New productivity challenge New productivity challenge

Knowledge workers Knowledge workers

Technology Technology

|

![]()

![]()