Innovation

about Peter Drucker — his other books

top of the food-chain

See the entrepreneurship and marketing companion pages

From “Progress to Innovation”

found in Landmarks of Tomorrow

Amazon link: Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Purposeful Innovation

Innovation is not a technical term.

It is an economic and social term.

Its criterion is not science or technology, but a change in the economic or social environment, a change in the behavior of people as consumers or producers, as citizens, as students or as teachers, and so on.

Innovation creates new wealth or new potential of action rather than new knowledge.

This means that the bulk of innovative efforts will have to come from the places that control the manpower and the money needed for development and marketing, that is, from the existing large aggregation of trained manpower and disposable money—existing businesses and existing public-service institutions — see below (calendarize this?)

“A key to innovation is not to try to be brilliant, but to be simple…. Sow small seeds and make them bear big fruit.” — Forbes

“The last policy for the change leader to build into the enterprise is a systematic policy of INNOVATION, that is, a policy to create change.

It is the area to which most attention is being given today.

It may, however, not be the most important one—organized abandonment, improvement, exploiting success may be more productive for a good many enterprises.

And without these policies—abandonment, improvement, exploitation—no organization can hope to be a successful innovator.

But to be a successful change leader an enterprise has to have a policy of systematic innovation.

And the main reason may not even be that change leaders need to innovate—though they do.

The main reason is that a policy of systematic innovation produces the mindset for an organization to be a change leader.

It makes the entire organization see change as an opportunity.”

— continues in Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Knowledge: Its economics and productivity

See chapter 2 in Landmarks of Tomorrow

(From Progress to Innovation ~ 1957)

The following are quotes from Peter Drucker's Innovation and Entrepreneurship plus an Inc. Magazine Interview on Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

The purpose of this introduction is to help readers determine what needs to be on their radar.

Innovation creates a new dimension of performance

The test of an innovation is whether it creates value.

Innovation means the creation of new value and new satisfaction for the customer.

A novelty only creates amusement.

Yet, again and again, managements decide to innovate for no other reason than that they are bored with doing the same thing or making the same product day in and day out.

The test of an innovation, as well as the test of “quality,” is not “Do we like it?”

It is “Do customers want it and will they pay for it?”

And it is change that always provides the opportunity for the new and different.

Systematic innovation therefore consists in the purposeful and organized search for changes, and in the systematic analysis of the opportunities such changes might offer for economic or social innovation.

Specifically, systematic innovation means monitoring seven sources for innovative opportunity.

As a rule, these are changes that have already occurred or are under way.

The overwhelming majority of successful innovations exploit change.

To be sure, there are innovations that in themselves constitute a major change; some of the major technical innovations, such as the Wright Brothers’ airplane, are examples.

But these are exceptions, and fairly uncommon ones.

Most successful innovations are far more prosaic; they exploit change.

And thus the discipline of innovation (and it is the knowledge base of entrepreneurship) is a diagnostic discipline: a systematic examination of the areas of change that typically offer entrepreneurial opportunities.

These executives know that it is as difficult and risky to convert a small idea into successful reality as it is to make a major innovation.

They do not aim at “improvements” or “modifications” in products or technology.

They aim at innovating a new business.

See Chapter 9, The Purpose and Objectives of a Business, in Management, Revised Edition

And they know that innovation is not a term of the scientist or technologist.

It is a term of the businessman.

For innovation means the creation of new value (something important) and new satisfaction for the customer.

Organizations therefore measure innovations not by their scientific or technological importance but by what they contribute to market and customer.

They consider social innovation as important as technological innovation.

A successful innovation aims at leadership.

It does not aim necessarily at becoming eventually a “big business”; in fact, no one can foretell whether a given innovation will end up as a big business or a modest achievement.

But if an innovation does not aim at leadership from the beginning, it is unlikely to be innovative enough, and therefore unlikely to be capable of establishing itself.

Strategies (to be discussed in Chapters 16 through 19) vary greatly, from those that aim at dominance in an industry or a market to those that aim at finding and occupying a small “ecological niche” in a process or market.

But all entrepreneurial strategies, that is, all strategies aimed at exploiting an innovation, must achieve leadership within a given environment.

Otherwise they will simply create an opportunity for the competition.

Changing Values and Characteristics

From chapter 19 of Innovation and Entrepreneurship by Peter Drucker

Amazon link: Innovation and Entrepreneurship

In the entrepreneurial strategies discussed so far, the aim is to introduce an innovation.

In the entrepreneurial strategy discussed in this chapter, the strategy itself is the innovation.

The product or service it carries may well have been around a long time—in our first example, the postal service, it was almost two thousand years old.

But the strategy converts this old, established product or service into something new.

It changes its utility, its value, its economic characteristics.

While physically there is no change, economically there is something different and new.

All the strategies to be discussed in this chapter have one thing in common.

They create a customer — and that is the ultimate purpose of a business, indeed, of economic activity.

As was first said more than thirty years ago in my The Practice of Management (New York: Harper & Row, 1954).

But they do so in four different ways:

by creating utility by creating utility

by pricing by pricing

by adaptation to the customer’s social and economic reality by adaptation to the customer’s social and economic reality

by delivering what represents true value to the customer by delivering what represents true value to the customer

... snip, snip ...

These examples are likely to be considered obvious.

Surely, anybody applying a little intelligence would have come up with these and similar strategies?

But the father of systematic economics, David Ricardo, is believed to have said once, “Profits are not made by differential cleverness, but by differential stupidity.”

The strategies work, not because they are clever, but because most suppliers—of goods as well as of services, businesses as well as public-service institutions—do not think.

They work precisely because they are so “obvious.”

Why, then, are they so rare?

For, as these examples show, anyone who asks the question, What does the customer really buy? will win the race.

In fact, it is not even a race since nobody else is running.

What explains this?

One reason is the economists and their concept of “value.”

Every economics book points out that customers do not buy a “product,” but what the product does for them.

And then, every economics book promptly drops consideration of everything except the “price” for the product, a “price” defined as what the customer pays to take possession or ownership of a thing or a service.

What the product does for the customer is never mentioned again.

Unfortunately, suppliers, whether of products or of services, tend to follow the economists.

It is meaningful to say that “product A costs X dollars.”

It is meaningful to say that “we have to get Y dollars for the product to cover our own costs of production and have enough left over to cover the cost of capital, and thereby to show an adequate profit.”

But it makes no sense at all to conclude and therefore the customer has to pay the lump sum of Y dollars in cash for each piece of product A he buys.”

Rather, the argument should go as follows: “What the customer pays for each piece of the product has to work out as Y dollars for us.

But how the customer pays depends on what makes the most sense to him.

It depends on what the product does for the customer.

It depends on what fits his reality.

It depends on what the customer sees as ‘value.’”

Price in itself is not “pricing,” and it is not “value.”

It was this insight that gave King Gillette a virtual monopoly on the shaving market for almost forty years; it also enabled the tiny Haloid Company to become the multibillion-dollar Xerox Company in ten years, and it gave General Electric world leadership in steam turbines.

In every single case, these companies became exceedingly profitable.

But they earned their profitability.

They were paid for giving their customers satisfaction, for giving their customers what the customers wanted to buy, in other words, for giving their customers their money’s worth.

“But this is nothing but elementary marketing,” most readers will protest, and they are right.

It is nothing but elementary marketing.

To start out with the customer’s utility, with what the customer buys, with what the realities of the customer are and what the customer’s values are—this is what marketing is all about.

But why, after forty years of preaching Marketing, teaching Marketing, professing Marketing, so few suppliers are willing to follow, I cannot explain.

The fact remains that so far, anyone who is willing to use marketing as the basis for strategy is likely to acquire leadership in an industry or a market fast and almost without risk.

Entrepreneurial strategies are as important as purposeful innovation and entrepreneurial management.

Together, the three make up innovation and entrepreneurship.

The available strategies are reasonably clear, and there are only a few of them.

But it is far less easy to be specific about entrepreneurial strategies than it is about purposeful innovation and entrepreneurial management.

We know what the areas are in which innovative opportunities are to be found and how they are to be analyzed.

There are correct policies and practices and wrong policies and practices to make an existing business or public-service institution capable of entrepreneurship; right things to do and wrong things to do in a new venture.

But the entrepreneurial strategy that fits a certain innovation is a high-risk decision.

Some entrepreneurial strategies are better fits in a given situation, for example, the strategy that I called entrepreneurial judo, which is the strategy of choice where the leading businesses in an industry persist year in and year out in the same habits of arrogance and false superiority.

We can describe the typical advantages and the typical limitations of certain entrepreneurial strategies.

Above all, we know that an entrepreneurial strategy has more chance of success the more it starts out with the users—their utilities, their values, their realities.

An innovation is a change in market or society.

It produces a greater yield for the user, greater wealth-producing capacity for society, higher value or greater satisfaction.

The test of an innovation is always what it does for the user.

Hence, entrepreneurship always needs to be market-focused, indeed, market-driven.

Still, entrepreneurial strategy remains the decision-making area of entrepreneurship and therefore the risk-taking one.

It is by no means hunch or gamble.

But it also is not precisely science.

Rather, it is judgment.

The test of an innovation, after all, lies not its novelty, its scientific content, or its cleverness.

It lies in its success in the marketplace

See conditions of survival

Above all, we know that an entrepreneurial strategy has more chance of success the more it starts out with the users—their utilities, their values, their realities.

An innovation is a change in market or society.

It produces a greater yield for the user, greater wealth-producing capacity for society, higher value or greater satisfaction.

The test of an innovation is always what it does for the user.

Hence, entrepreneurship always needs to be market-focused, indeed, market-driven

Do You Match Up Ideas With The Opportunity?

Will the idea respond effectively to the real-world opportunity?

Finding the answer to this question falls somewhere between science and intuition.

An idea is a possible mechanism for serving a customer need, such as a pink cell phone.

Opportunities are unmet customer needs, such as the customer’s desire to be stylish.

The challenge is to assess the scope of the need and the ability of the idea to meet that need.

With the proper analysis—often utilizing targeted market research—you can predict in many cases which ideas will be successful.

Aim high!

Minor modifications rarely address unmet needs.

When I spoke to Peter about this, he leaned back in his chair and told me: “If an innovation does not aim at leadership from the beginning, it is unlikely to be innovative enough to change the customers’ habits.”

He continued, “Aiming high is aiming for something that will make the enterprise capable of genuine innovation and self-renewal.

That means inventing [(creating?)] a new business and not just a product-line extension, reaching a new performance capacity and not just an incremental improvement, and delivering new, unimagined value, and not just satisfying existing expectations better.”

But how do we know what’s right?

“Most good ideas will not generate enough wealth to replicate the business’s historical success, and many more will fail,” Peter explained.

“Thus, the need to aim high is a practical reality; the one big success is needed to offset the nine failures.”

At the same time, Peter always stressed the need to be practical.

When it came to innovation, he felt that the most practical approach was to use the absolutely best people.

In many ways this is the art of innovation: remaining practical while having the courage to aim high.

The criteria listed in the box on the next page help assess whether an idea matches an opportunity and whether you are aiming high enough while still taking market realities into account.

The analysis must also address the risks of success, of near success, and of failure.

The Definitive Drucker

Q: Would you define entrepreneur?

A: The definition is very old. It is somebody who endows resources with new wealth-producing capacity. That’s all.

Entrepreneurship is not a romantic subject. It’s hard work

We have reached the point [in entrepreneurial management] where we know what the practice is, and it’s not waiting around for the muse to kiss you. The muse is very, very choosy, not only in whom she kisses but in where she kisses them. And so one can’t wait.

Q: You make the point that small business and entrepreneurial business are not necessarily the same thing.

A: The great majority of small businesses are incapable of innovation, partly because they don’t have the resources, but a lot more because they don’t have the time and they don’t have the ambition.

I’m not even talking of the corner cigar store.

Look at the typical small business.

It’s grotesquely understaffed.

It doesn’t have the resources and the cash flow.

Maybe the boss doesn’t sweep the store anymore, but he’s not that far away.

He’s basically fighting the daily battle.

He doesn’t have, by and large, the discipline.

He doesn’t have the background.

The most successful of the young entrepreneurs today are people who have spent five to eight years in a big organization.

Q: What does that do for them?

A: They learn. They get tools. They learn how to do a cash-flow analysis and how one trains people and how one delegates and how one builds a team. The ones without that background are the entrepreneurs who, no matter how great their success, are being pushed out.

You see, there is entrepreneurial work and there is managerial work, and the two are not the same (and most people can do both).

(But not everybody is attracted to them equally.

The young man I told you about who starts companies, he asked himself the question, and his answer was, “I don’t want to run a business.”)

But you can’t be a successful entrepreneur unless you manage, and if you try to manage without some entrepreneurship, you are in danger of becoming a bureaucrat.

Yes, the work is different, but that’s not so unusual

Successful entrepreneurs, whatever their individual motivation—be it money, power, curiosity, or the desire for fame and recognition—try to create value and to make a contribution.

Still, successful entrepreneurs aim high.

They are not content simply to improve on what already exists, or to modify it.

They try to create new and different values and new and different satisfactions, to convert a “material” into a “resource,” or to combine existing resources in a new and more productive configuration.

The Entrepreneurial Investor

From The Daily Drucker

The capital market decisions are effectively shifting from the “entrepreneurs” to the “trustees,” from the people who are supposed to invest in the future to the people who have to follow the “prudent man rule,” which means, in effect, investing in past performance.

Herein lies a danger of starving the new, the young, the small, the growing business.

But this is happening at a time when the need for new businesses is particularly urgent, whether they are based on new technology or engaged in converting social and economic needs into business opportunities.

It requires quite different skills and different rules to invest in the old and existing as opposed to the new ventures.

The person who is investing in what already exists is, in effect, trying to minimize risk.

He invests in established trends and markets, in proven technology and management performance.

The entrepreneurial investor must operate on the assumption that out of ten investments, seven will go sour and have to be liquidated with more or less a total loss.

There is no way to judge in advance which of the ten investments in the young and the new will turn out failures and which will succeed.

The entrepreneurial skill does not lie in “picking investments.”

It lies in knowing what to abandon because it fails to pan out, and what to push and support with full force because it “looks right” despite some initial setbacks.”

The Entrepreneurial Business

“Big businesses don’t innovate,” says the conventional wisdom.

This sounds plausible enough.

True, the new, major innovations of this century did not come out of the old, large businesses of their time.

The railroads did not spawn the automobile or the truck; they did not even try.

And though the automobile companies did try (Ford and General Motors both pioneered in aviation and aerospace), all of today’s large aircraft and aviation companies have evolved out of separate new ventures.

Similarly, today’s giants of the pharmaceutical industry are, in the main, companies that were small or nonexistent fifty years ago when the first modern drugs were developed.

Every one of the giants of the electrical industry—General Electric, Westinghouse, and RCA in the United States; Siemens and Philips on the Continent; Toshiba in Japan—rushed into computers in the 1950s.

Not one was successful.

The field is dominated by IBM, a company that was barely middle-sized and most definitely not high-tech forty years ago.

And yet the all but universal belief that large businesses do not and cannot innovate is not even a half-truth; rather, it is a misunderstanding.

In the first place, there are plenty of exceptions, plenty of large companies that have done well as entrepreneurs and innovators.

In the United States, there is Johnson & Johnson in hygiene and health care, and 3M in highly engineered products for both industrial and consumer markets.

Citibank, America’s and the world’s largest nongovernmental financial institution, well over a century old, has been a major innovator in many areas of banking and finance.

In Germany, Hoechst—one of the world’s largest chemical companies, and more than 125 years old by now—has become a successful innovator in the pharmaceutical industry.

In Sweden, ASEA, founded in 1884 and for the last sixty or seventy years a very big company, is a true innovator in both long-distance transmission of electrical power and robotics for factory automation.

To confuse things even more there are quite a few big, older businesses that have succeeded as entrepreneurs and innovators in some fields while failing dismally in others.

The (American) General Electric Company failed in computers, but has been a successful innovator in three totally different fields: aircraft engines, engineered inorganic plastics, and medical electronics.

RCA also failed in computers but succeeded in color television.

Surely things are not quite as simple as the conventional wisdom has it.

Secondly, it is not true that “bigness” is an obstacle to entrepreneurship and innovation.

In discussions of entrepreneurship one hears a great deal about the “bureaucracy” of big organizations and of their “conservatism.”

Both exist, of course, and they are serious impediments to entrepreneurship and innovation—but to all other performance just as much.

And yet the record shows unambiguously that among existing enterprises, whether business or public-sector institutions, the small ones are least entrepreneurial and least innovative.

Among existing entrepreneurial businesses there are a great many very big ones; the list above could have been enlarged without difficulty to one hundred companies from all over the world, and a list of innovative public-service institutions would also include a good many large ones.

And perhaps the most entrepreneurial business of them all is the large middle-sized one, such as the American company with $500 million in sales in the mid-1980s.

But small existing enterprises would be conspicuously absent from any list of entrepreneurial businesses.

It is not size that is an impediment to entrepreneurship and innovation; it is the existing operation itself, and especially the existing successful operation.

And it is easier for a big or at least a fair-sized company to surmount this obstacle than it is for a small one.

Operating anything—a manufacturing plant, a technology, a product line, a distribution system—requires constant effort and unremitting attention.

The one thing that can be guaranteed in any kind of operation is the daily crisis.

The daily crisis cannot be postponed, it has to be dealt with right away.

And the existing operation demands high priority and deserves it.

The new always looks so small, so puny, so unpromising next to the size and performance of maturity.

Anything truly new that looks big is indeed to be distrusted.

The odds are heavily against its succeeding.

And yet successful innovators, as was argued earlier, start small and, above all, simple.

The claim of so many businesses, “Ten years from now, ninety percent of our revenues will come from products that do not even exist today,” is largely boasting.

Modifications of existing products, yes; variations, yes; even extensions of existing products into new markets and new end uses—with or without modifications.

But the truly new venture tends to have a longer lead time.

Successful businesses, businesses that are today in the right markets with the right products or services, are likely ten years hence to get three-quarters of their revenues from products and services that exist today, or from their linear descendants.

In fact, if today’s products or services do not generate a continuing and large revenue stream, the enterprise will not be able to make the substantial investment in tomorrow that innovation requires.

It thus takes special effort for the existing business to become entrepreneurial and innovative.

The “normal” reaction is to allocate productive resources to the existing business, to the daily crisis, and to getting a little more out of what we already have.

The temptation in the existing business is always to feed yesterday and to starve tomorrow.

Organization efforts ::: Problems or Opportunities?

It is, of course, a deadly temptation.

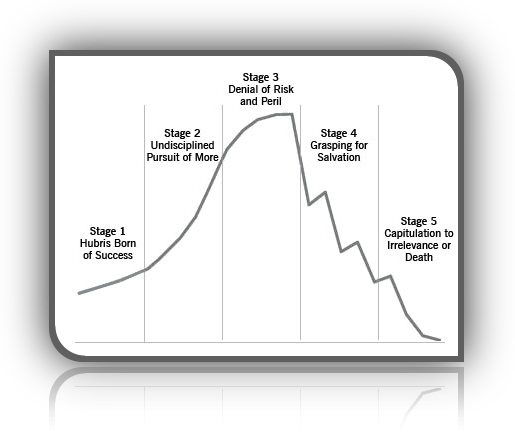

The enterprise that does not innovate inevitably ages and declines.

And in a period of rapid change such as the present, an entrepreneurial period, the decline will be fast.

Once an enterprise or an industry has started to look back, turning it around is exceedingly difficult, if it can be done at all.

But the obstacle to entrepreneurship and innovation which the success of the present business constitutes is a real one.

The problem is precisely that the enterprise is so successful, that it is “healthy” rather than degeneratively diseased by bureaucracy, red tape, or complacency.

This is what makes the examples of existing businesses that do manage successfully to innovate so important, and especially the examples of existing large and fair-sized businesses that are also successful entrepreneurs and innovators.

These businesses show that the obstacle of success, the obstacle of the existing, can be overcome.

And it can be overcome in such a way that both the existing and the new, the mature and the infant, benefit and prosper.

The large companies that are successful entrepreneurs and innovators—Johnson & Johnson, Hoechst, ASEA, 3M, or the one hundred middle-sized “growth” companies—clearly know how to do it.

Where the conventional wisdom goes wrong is in its assumption that entrepreneurship and innovation are natural, creative, or spontaneous.

If entrepreneurship and innovation do not well up in an organization, something must be stifling them.

That only a minority of existing successful businesses are entrepreneurial and innovative is thus seen as conclusive evidence that existing businesses quench the entrepreneurial spirit.

But entrepreneurship is not “natural”; it is not “creative.”

It is work.

Hence, the correct conclusion from the evidence is the opposite of the one commonly reached.

That a substantial number of existing businesses, and among them a goodly number of fair-sized, big, and very big ones, succeed as entrepreneurs and innovators indicates that entrepreneurship and innovation can be achieved by any business.

But they must be consciously striven for.

They can be learned, but it requires effort.

Entrepreneurial businesses treat entrepreneurship as a duty.

They are disciplined about it … they work at it … they practice it.

Specifically, entrepreneurial management requires policies and practices in four major areas.

First, the organization must be made receptive to innovation and willing to perceive change as an opportunity rather than a threat.

It must be organized to do the hard work of the entrepreneur. Policies and practices are needed to create the entrepreneurial climate.

Second, systematic measurement or at least appraisal of a company’s performance as entrepreneur and innovator is mandatory, as well as built-in learning to improve performance.

Third, entrepreneurial management requires specific practices pertaining to organizational structure, to staffing and managing, and to compensation, incentives, and rewards.

Fourth, there are some “dont’s”: things not to do in entrepreneurial management

—Chapter 13 Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Creativity from Chapter 10 of Management, Revised Edition

Try a MRE page search for the word stem “creat”

To make the future happen one need not, in other words, have a creative imagination.

It requires work rather than genius—and therefore is accessible in some measure to everybody.

The man of creative imagination will have more imaginative ideas, to be sure.

But that the more imaginative idea will actually be more successful is by no means certain.

Pedestrian ideas have at times been successful;

Bata’s idea of applying American methods to making shoes was not very original in the Europe of 1920, with its tremendous interest in Ford and his assembly line.

What mattered was his courage rather than his genius.

To make the future happen one has to be willing to do something new.

One has to be willing to ask,

“What do we really want to see happen that is quite different from today?”

One has to be willing to say,

“This is the right thing to happen as the future of the business.

We will work on making it happen.”

Lack of “creativity,” which looms so large in present discussions of innovation, is not the real problem.

There are more ideas in any organization, including businesses, than can possibly be put to use.

What is lacking, as a rule, is the willingness to look beyond products to ideas.

[See Sur/petition]

Products and processes are only the vehicle through which an idea becomes effective.

See piloting and strategies

Dense reading and Dense listening and Thinking broad and Thinking detailed

And, as the illustrations should have shown, the specific future products and processes can usually not even be imagined.

When DuPont started the work on polymer chemistry out of which nylon eventually evolved, it did not know that man-made fibers would be the end product.

DuPont acted on the assumption that any gain in man’s ability to manipulate the structure of large, organic molecules—at that time in its infancy—would lead to commercially important results of some kind.

Only after six or seven years of research work did man-made fibers first appear as a possible major result area.

Moreover, the manager often lacks the courage to commit resources to such an idea.

The resources that should be invested in making the future happen should be small, but they must be of the best.

Otherwise nothing happens.

However, the greatest lack of the manager is a touchstone of validity and practicality.

An idea has to meet rigorous tests if it is to be capable of making the future of a business.

It has to have operational validity.

Can we take action on this idea?

Or can we only talk about it?

Can we really do something right away to bring about the kind of future we want to make happen?

To be able to spend money on research is not enough.

It must be research directed toward the realization of the idea.

The knowledge sought may be general, as was that of DuPont’s project.

But it must at least be reasonably clear that if available, it would be applicable knowledge.

The idea must also have economic validity.

If it could be put to work right away in practice, it should be able to produce economic results.

We may not be able to do what we would like to for a long time, perhaps never.

But if we could do it now, the resulting products, processes, or services would find a customer, a market, an end-use; should be capable of being sold profitably; should satisfy a want and a need.

The idea itself might aim at social reform.

But unless an organization can be built on it, it is not a valid entrepreneurial idea.

The test of the idea is not the votes it gets or the acclaim of the philosophers.

It is economic performance and economic results.

Even if the rationale of the business is social reform rather than business success, the touchstone must be the ability to perform and to survive as a business.

Finally, the idea must meet the test of personal commitment.

Do we really believe in the idea?

Do we really want to be that kind of people, do that kind of work, run that kind of business?

To make the future demands courage.

It demands work.

But it also demands faith.

To commit ourselves to the expedient is simply not practical.

It will not suffice for the tests ahead.

For no such idea is foolproof—nor should it be.

The one idea regarding the future that must inevitably fail is the apparently “sure thing,” the “riskless idea,” the one “that cannot fail.”

The idea on which tomorrow’s business is to be built must be uncertain; no one can really say as yet what it will look like if and when it becomes reality.

It must be risky:

it has a probability of success but also of failure.

If it is not both uncertain and risky, it is simply not a practical idea for the future.

For the future itself is both uncertain and risky.

Unless there is personal commitment to the values of the idea and faith in them, the necessary efforts will therefore not be sustained.

The manager should not become an enthusiast, let alone a fanatic.

She should realize that things do not happen just because she wants them to happen—not even if she works very hard at making them happen.

Like any other effort, the work on making the future happen should be reviewed periodically to see whether continuation can still be justified both by the results of the work to date and by the prospects ahead.

Ideas regarding the future can become investments in managerial ego too, and need to be carefully tested for their capacity to perform and to give results.

But the people who work on making the future also need to be able to say with conviction, “This is what we really want our business to be.”

It is perhaps not absolutely necessary for every organization to search for the idea that will make the future.

A good many organizations and their managements do not even make their present organizations effective—and yet the organizations somehow survive for a while.

The big business, in particular, seems to be able to coast a long time on the courage, work, and vision of earlier managers.

But tomorrow always arrives.

It is always different.

And then even the mightiest company is in trouble if it has not worked on the future.

It will have lost distinction and leadership—all that will remain is big-company overhead.

It will neither control nor understand what is happening.

Not having dared to take the risk of making the new happen, it perforce took the much greater risk of being surprised by what did happen.

And this is a risk that even the largest and richest organization cannot afford and that even the smallest one need not run.

To be more than a slothful steward of the talents in one’s keeping, the manager has to accept responsibility for making the future happen.

It is the willingness to tackle this purposefully that distinguishes the great organization from the merely competent one, and the organization builder from the manager-suite custodian.

A scorecard for managers A scorecard for managers

Company performance: five telltale tests Company performance: five telltale tests

Without an effective mission statement, there will be no performance Without an effective mission statement, there will be no performance

Continuity and change Continuity and change

Look Look

Management Challenges for the 21st Century Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Making the future Making the future

Managing in the Next Society Managing in the Next Society

The Shakeout (calendarize this?)

The “shakeout” sets in as soon as the “window” closes.

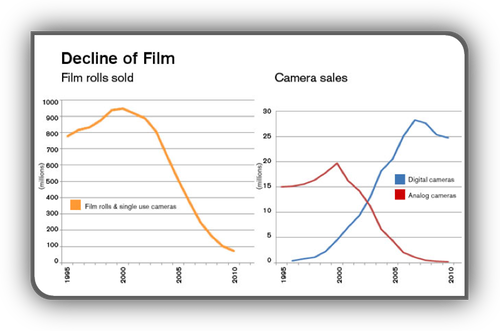

And the majority of ventures started during the “window” period do not survive the shakeout, as has already been shown for such high-tech industries of yesterday as railroads, electrical apparatus makers, and automobiles.

As these lines are being written, the shakeout has begun among microprocessor, minicomputer, and personal computer companies—only five or six years after the “window” opened.

Today, there are perhaps a hundred companies in the industry in the United States alone.

Ten years hence, by 1995, there are unlikely to be more than a dozen left of any size or significance.

But which ones will survive, which ones will die, and which ones will become permanently crippled—able neither to live nor to die—is unpredictable.

In fact, it is futile to speculate.

Sheer size may ensure survival.

But it does not guarantee success in the shakeout, otherwise Allied Chemical rather than DuPont would today be the world’s biggest and most successful chemical company.

In 1920, when the “window” opened for the chemical industry in the United States, Allied Chemical looked invincible, if only because it had obtained the German chemical patents which the U.S. government had confiscated during World War I.

Seven years later, after the shakeout, Allied Chemical had become a weak also-ran.

It has never been able to regain momentum.

No one in 1949 could have predicted that IBM would emerge as the computer giant, let alone that such big, experienced leaders as G.E. or Siemens would fail completely.

No one in 1910 or 1914 when automobile stocks were the favorites of the New York Stock Exchange could have predicted that General Motors and Ford would survive and prosper and that such universal favorites as Packard or Hupmobile would disappear.

No one in the 1870s and 1880s, the period in which the modern banks were born, could have predicted that Deutsche Bank would swallow up dozens of the old commercial banks of Germany and emerge as the leading bank of the country.

That a certain industry will become important is fairly easy to predict.

There is no case on record where an industry that reached the explosive phase, the “window” phase, as I called it, has then failed to become a major industry.

The question is, Which of the specific units in this industry will be its leaders and so survive?

This rhythm—a period of great excitement during which there is also great speculative ferment, followed by a severe “shakeout”—is particularly pronounced in the high-tech industries.

In the first place, such industries are in the limelight and thus attract far more entrants and far more capital than more mundane areas.

Comments by Warren Buffett.

Also the expectations are much greater.

More people have probably become rich building such prosaic businesses as a shoe-polish or a watchmaking company than have become rich through high-tech businesses.

Yet no one expects shoe-polish makers to build a “billion-dollar business,” nor considers them a failure if all they build is a sound but modest family company.

(Managing the Family Business: see December 28 and 29 in The Daily Drucker)

High tech, by contrast, is a “high-low game,” in which a middle hand is considered worthless.

And this makes high-tech innovation inherently risky.

But also, high tech is not profitable for a very long time.

The world’s computer industry began in 1947-48.

Not until the early 1980s, more than thirty years later, did the industry as a whole reach break-even point.

To be sure, a few companies (practically all of them American, by the way) began to make money much earlier.

And one, IBM, the leader, began to make a great deal of money earlier still.

But across the industry the profits of those few successful computer makers were more than offset by the horrendous losses of the rest; the enormous losses, for instance, which the big international electrical companies took in their abortive attempts to become computer manufacturers.

And exactly the same thing happened in every earlier “high-tech” boom—in the railroad booms of the early nineteenth century, in the electrical apparatus and the automobile booms between 1880 and 1914, in the electric appliance and the radio booms of the 1920s, and so on.

One major reason for this is the need to plow more and more money back into research, technical development, and technical services to stay in the race.

High tech does indeed have to run faster and faster in order to stand still.

This is, of course, part of its fascination.

But it also means that when the shakeout comes, very few businesses in the industry have the financial resources to outlast even a short storm.

This is the reason why high-tech ventures need financial foresight even more than other new ventures, but also the reason why financial foresight is even scarcer among high-tech new ventures than it is among new ventures in general.

(Find “financial foresight” in Innovation and Entrepreneurship and see chapter 3 in The Changing World of the Executive)

There is only one prescription for survival during the shakeout: entrepreneurial management (described in Chapters 12-15).

What distinguished Deutsche Bank from the other “hot” financial institutions of its time was that Georg Siemens thought through and built the world’s first top management team.

What distinguished DuPont from Allied Chemical was that DuPont in the early twenties created the world’s first systematic organization structure, the world’s first long-range planning, and the world’s first system of management information and control.

Allied Chemical, by contrast, was run arbitrarily by one brilliant egomaniac.

But this is not the whole story.

Most of the large companies that failed to survive the more recent computer shakeout — G.E. and Siemens, for instance—are usually considered to have first-rate management.

And the Ford Motor Company survived, though only by the skin of its teeth, even though it was grotesquely mismanaged during the shakeout years.

Entrepreneurial management is thus probably a precondition of survival, but not a guarantee thereof.

And at the time of the shakeout, only insiders (and perhaps not even they) can really know whether a knowledge-based innovator that has grown rapidly for a few boom years is well managed, as DuPont was, or basically unmanaged, as Allied Chemical was.

By the time we do know, it is likely to be too late.

Innovation and Entrepreneurship

9 JUL — Each Organization Must Innovate

Every organization needs one core competence: innovation.

Core competencies are different for every organization; they are, so to speak, part of an organization’s personality.

But every organization—not just businesses—needs one core competence: innovation.

And every organization needs a way to record and appraise its innovative performance.

In organizations already doing that—among them, several top flight pharmaceutical manufacturers—the starting point is not the company’s own performance.

It is a careful record of the innovations in the entire field during a given period.

Which of them were truly successful?

How many of them were ours?

Is our performance commensurate with our objectives?

With the direction of the market?

With our market standing?

With our research spending?

Are our successful innovations in the areas of greatest growth and opportunity?

How many of the truly important innovation opportunities did we miss?

Why?

Because we did not see them?

Or because we saw them but dismissed them?

Or because we botched them?

And how well do we do in converting an innovation into a commercial product?

A good deal of that, admittedly, is assessment rather than measurement.

It raises rather than answers questions, but it raises the right questions.

The Daily Drucker

Piloting from Management, Revised Edition

“Enterprises of all kinds increasingly use all kinds of market research and customer research to limit, if not eliminate, the risks of change.

But one cannot market research the truly new.

Also nothing new is right the first time.

Invariably, problems crop up that nobody even thought of.

Invariably, problems that loomed very large to the originator turn out to be trivial or not to exist at all.

Above all, the way to do the job invariably turns out to be different from what was originally designed.

It is almost a “law of nature” that anything that is truly new, whether product or service or technology, finds its major market and its major application not where the innovator and entrepreneur expected, and not to be the use for which the innovator or entrepreneur has designed it.

And that, no market or customer research can possibly discover.

The best example is an early one:

The improved steam engine that James Watt (1736-1819) designed and patented in 1776 is the event that, for most people, signifies the advent of the Industrial Revolution.

Actually, Watt until his death saw only one use for the steam engine: to pump water out of coal mines.

That was the use for which he had designed it.

And he sold it only to coal mines.

It was his partner, Matthew Boulton (1728-1809), who was the real father of the Industrial Revolution.

Boulton saw that the improved steam engine could be used in what was then England’s premier industry, textiles, and especially in the spinning and weaving of cotton.

Within ten or fifteen years after Boulton had sold his first steam engine to a cotton mill, the price of cotton textiles had fallen by 70 percent.

And this created both the first mass market and the first factory—and together modern capitalism and the modern economy altogether.

Neither studies nor market research not computer modeling are a substitute for the test of reality.

Everything improved or new needs, therefore, first to be tested on a small scale, that is, it needs to be piloted.

The way to do this is to find somebody within the enterprise who really wants the new.

As said before, everything new gets into trouble.

And then it needs a champion.

It needs somebody who says, “I am going to make this succeed,” and who then goes to work on it.

And this person needs to be somebody whom the organization respects.

This need not even be somebody within the organization.

A good way to pilot a new product or new service is often to find a customer who really wants the new, and who is willing to work with the producer on making the new product or the new service truly successful.

If the pilot test is successful—if it finds the problems nobody anticipated but also finds the opportunities that nobody anticipated, whether in terms of design, of market, of service—the risk of change is usually quite small.

And it is usually also quite clear where to introduce the change and how to introduce it, that is, what entrepreneurial strategy to employ.”

Exploiting Innovative Ideas

Creativity is sexy, but the real problem is the shockingly high mortality rate of healthy new products or services.

There usually are more good ideas in even the stodgiest organization than can possibly be exploited.

The real problem is the shockingly high mortality rate of healthy new products or services.

And like yesterday’s infant mortality rate, the mortality rate of new products and services is totally unnecessary.

It can be reduced fairly fast and without spending a great deal of money.

Much of it is simply the result of ignorance of the entrepreneurial strategies.

The right entrepreneurial strategy has a very high chance of success.

There are four specifically entrepreneurial strategies aiming at market leadership:

Being “Fustest with the Mostest”; Being “Fustest with the Mostest”;

“Hitting Them Where They Ain’t”; “Hitting Them Where They Ain’t”;

Finding and occupying a specialized “ecological niche”; and Finding and occupying a specialized “ecological niche”; and

Changing the economic characteristics of a product, a market, or an industry. Changing the economic characteristics of a product, a market, or an industry.

These four strategies are not mutually exclusive.

One and the same entrepreneur often combines two, sometimes even elements of three, in one strategy.

Still, each of these four has its prerequisites.

Each fits certain kinds of innovation and does not fit others.

Each requires specific behavior on the part of the entrepreneur.

Finally, each has its own limitations and carries its own risks.

The Daily Drucker

Other Innovation and Entrepreneurship pages

Entrepreneurship topic page—a placeholder Entrepreneurship topic page—a placeholder

Innovation and Entrepreneurship book outline with an exploration of Systematic Entrepreneurship. (Look for the word “simple” in the full text) Innovation and Entrepreneurship book outline with an exploration of Systematic Entrepreneurship. (Look for the word “simple” in the full text)

Entrepreneurs and Innovation Peter Drucker interview conducted by George Gendron, editor in chief of Inc. magazine Entrepreneurs and Innovation Peter Drucker interview conducted by George Gendron, editor in chief of Inc. magazine

The Change Leader in Management Challenges for the 21st Century The Change Leader in Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Chapter 30 “The Innovative Organization” and “Afterword: Social Innovation — Management’s New Dimension” in The Frontiers of Management Chapter 30 “The Innovative Organization” and “Afterword: Social Innovation — Management’s New Dimension” in The Frontiers of Management

“Afterword: The 1990s and Beyond” in Managing for the Future “Afterword: The 1990s and Beyond” in Managing for the Future

Marketing and Innovation in a society moving in time Marketing and Innovation in a society moving in time

Council on Competitiveness Urges National Innovation Ecosystem to Lead Next Wave of U.S. Economic Growth Council on Competitiveness Urges National Innovation Ecosystem to Lead Next Wave of U.S. Economic Growth

Management, Revised Edition contains several innovation and entrepreneurship topics Management, Revised Edition contains several innovation and entrepreneurship topics

The Definitive Drucker The Definitive Drucker

Peter Drucker book list: Toward tomorrows, comprehensive management and time related Peter Drucker book list: Toward tomorrows, comprehensive management and time related

Search books by Peter Drucker for the word stems: innovat or entrepren Search books by Peter Drucker for the word stems: innovat or entrepren

See Part III Thinking for opportunities in Edward de Bono’s Opportunities See Part III Thinking for opportunities in Edward de Bono’s Opportunities

Edward de Bono’s Serious Creativity Edward de Bono’s Serious Creativity

Reality Check by Guy Kawasaki Reality Check by Guy Kawasaki

So, what are you going to calendarize?

List of topics in this Folder

|

![]()

![]()