|

Just reading is not enough … #ams

Concepts have to be converted into daily action

Harvesting and action thinking are needed …

Managing oneself should be the action foundation

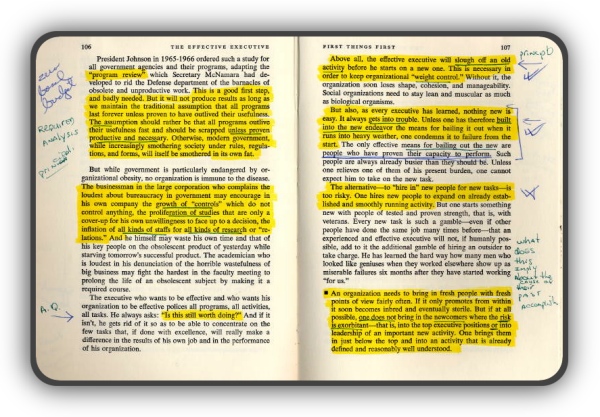

You can select and note areas of interest. You can employ what does this mean for me? (illustration) with the PMI, dense reading and dense listening plus thinking broad and thinking detailed with operacy to see where that takes you. The potential effectiveness of our thinking depends on our existing mental landscape → see experts speak. What’s the next effective action?

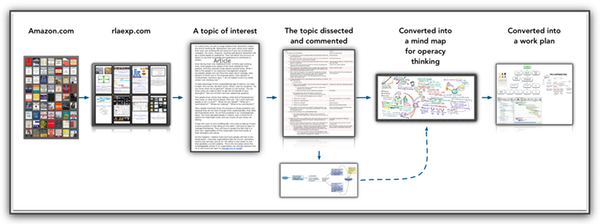

Concept acquisition → action conversion → click image ↓

When we are involved in doing something, it is very difficult

to look outside that involvement — even when our future depends on it.

Additionally, everything eventually outlives its usefulness continue

And now for the rest of the story

Preface

Forty years ago, when I first began to work with non-profit institutions, they were generally seen as marginal to an American society dominated by government and big business respectively.

In fact, the non-profits themselves by and large shared this view.

We then believed that government could and should discharge all major social tasks, and that the role of the non-profits, if any, was to supplement governmental programs or to add special flourishes to them.

Today, we know better.

Today, we know that the non-profit institutions are central to American society and are indeed its most distinguishing feature.

We now know that the ability of government to perform social tasks is very limited indeed.

But we also know that the non-profits discharge a much bigger job than taking care of specific needs.

With every second American adult serving as a volunteer in the non-profit sector and spending at least three hours a week in non-profit work, the non-profits are America’s largest “employer.”

But they also exemplify and fulfill the fundamental American commitment to responsible citizenship in the community.

The non-profit sector still represents about the same proportion of America’s gross national product—2 to 3 percent—as it did forty years ago.

But its meaning has changed profoundly.

We now realize that it is central to the quality of life in America, central to citizenship, and indeed carries the values of American society and of the American tradition.

Forty years ago no one talked of “non-profit organizations” or of a “non-profit sector.”

Hospitals saw themselves as hospitals, churches as churches, Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts as Scouts, and so on.

Since then, we have come to use the term “nonprofit” for all these institutions.

It is a negative term and tells us only what these institutions are not.

But at least it shows that we have come to realize that all these institutions, whatever their specific concerns, have something in common.

And we now begin to realize what that “something” is.

It is not that these institutions are “nonprofit,” that is, that they are not businesses.

It is also not that they are “non-governmental.”

It is that they do something very different from either business or government.

Business supplies, either goods or services.

Government controls.

A business has discharged its task when the customer buys the product, pays for it, and is satisfied with it.

Government has discharged its function when its policies are effective.

The “non-profit” institution neither supplies goods or services nor controls.

Its “product” is neither a pair of shoes nor an effective regulation.

Its product is a changed human being.

The non-profit institutions are human-change agents.

Their “product” is a cured patient, a child that learns, a young man or woman grown into a self-respecting adult; a changed human life altogether.

Forty years ago, “management” was a very bad word in nonprofit organizations.

It meant “business” to them, and the one thing they were not was a business.

Indeed, most of them then believed that they did not need anything that might be called “management.”

After all, they did not have a “bottom line.”

For most Americans, the word “management” still means business management.

Indeed, newspaper or television reporters who interview me are always amazed to learn that I am working with non-profit institutions.

“What can you do for them?” they ask me, “Help them with fund-raising?”

And when I answer, “No, we work together on their mission, their leadership, their management,” the reporter usually says, “But that’s business management, isn’t it?”

But the “non-profit” institutions themselves know that they need management all the more because they do not have a conventional “bottom line.”

They know that they need to learn how to use management as their tool lest they be overwhelmed by it.

They know they need management so that they can concentrate on their mission.

Indeed, there is a “management boom” going on among the nonprofit institutions, large and small.

Yet little that is so far available to the non-profit institutions to help them with their leadership and management has been specifically designed for them.

Most of it was originally developed for the needs of business.

Little of it pays any attention to the distinct characteristics of the non-profits or to their specific central needs:

To their mission, which distinguishes them so sharply from business and government;

to what are “results” in non-profit work;

to the strategies required to market their services and obtain the money they need to do their job;

or to the challenge of introducing innovation and change in institutions that depend on volunteers and therefore cannot command.

Even less do the available materials focus on the specific human and organizational realities of non-profit institutions;

on the very different role that the board plays in the non-profit institution;

on the need to attract volunteers, to develop them, and to manage them for performance;

on relationships with a diversity of constituencies;

on fund-raising and fund development;

or (a very different matter) on the problem of individual burnout, which is so acute in non-profits precisely because the individual commitment to them tends to be so intense.

There is thus a real need among the non-profits for materials that are specifically developed out of their experience and focused on their realities and concerns.

material deleted for brevity

This book starts out with the realization that the non-profit institution has been America’s resounding success in the last forty years.

In many ways it is the “growth industry” of America, whether we talk

of health-care institutions like the American Heart Association or the American Cancer Society which have given leadership in research on major diseases and in their prevention and treatment;

of community’ services such as the Girl Scouts of the U.S.A. and the Boy Scouts of the U.S.A. which, respectively, are the world’s largest women’s and men’s organizations;

of the fast growing pastoral churches;

of the hospital;

or of the many other non-profit institutions that have emerged as the center of effective social action in a rapidly changing and turbulent America.

The non-profit sector has become America’s “Civil Society.”

Today, however, the non-profits face very big and different challenges.

The first is to convert donors into contributors.

In total amounts, the non-profit organizations in this country collect many times what they did forty years ago when I first worked with them.

But it is still the same share of the gross national product (2-3 percent), and I consider it a national disgrace, indeed a real failure, that the affluent, well-educated young people give proportionately less than their so much poorer blue-collar parents used to give.

If the health of a sector in the economy is judged by its share of the GNP, the non-profits do not look healthy at all.

The share of GNP that goes to leisure has more than doubled in the last forty years; the share that goes to medical care has gone up from 2 percent of the GNP to 11 percent; the share that goes to education, especially to colleges and universities, has tripled.

Yet the share that is being given by the American people to the non-profit, human-change agents has not increased at all.

We know that we can no longer hope to get money from “donors”; they have to become “contributors.”

This I consider to be the first task ahead for non-profit institutions.

It is much more than just getting extra money to do vital work.

Giving is necessary above all so that the non-profits can discharge the one mission they all have in common: to satisfy the need of the American people for self-realization, for living out our ideals, our beliefs, our best opinion of ourselves.

To make contributors out of donors means that the American people can see what they want to see—or should want to see—when each of us looks at himself or herself in the mirror in the morning: someone who as a citizen takes responsibility.

Someone who as a neighbor cares.

Then there is the second major challenge for the non-profits: to give community and common purpose.

Forty years ago, most Americans already no longer lived in small towns, but they had still grown up in one.

They had grown up in a local community.

It was a compulsory community and could be quite stifling.

Still, it was a community.

Today, the great majority of Americans live in big cities and their suburbs.

They have moved away from their moorings, but they still need a community.

And it is working as unpaid staff for a non-profit institution that gives people a sense of community, gives purpose, gives direction—whether it is work with the local Girl Scout troop, as a volunteer in the hospital, or as the leader of a Bible circle in the local church.

Again and again when I talk to volunteers in non-profits, I ask, “Why are you willing to give all this time when you are already working hard in your paid job?”

And again and again I get the same answer, “Because here I know what I am doing.

Here I contribute.

Here I am a member of a community.”

The non-profits are the American community.

They increasingly give the individual the ability to perform and to achieve.

Precisely because volunteers do not have the satisfaction of a paycheck, they have to get more satisfaction out of their contribution.

They have to be managed — not supervised — as unpaid staff.

But most non-profits still have to learn how to do this.

A clear mission A clear mission

Careful placement Careful placement

Continuous learning and teaching Continuous learning and teaching

Management by objectives and self-control Management by objectives and self-control

High demands but corresponding responsibility and accountability for performance and results High demands but corresponding responsibility and accountability for performance and results

And I hope to show them ↑ how—not by preaching, but by giving successful examples.

Post-Capitalist Society ↓

The need for people to make the future

The return of tribalism

Citizenship through the social sector

The social sector in a century of social transformation

↓

Chapter Summaries

The mission comes first and your role as a leader The mission comes first and your role as a leader

From mission to performance: effective strategies for marketing, innovation, and fund development From mission to performance: effective strategies for marketing, innovation, and fund development

Managing for performance: how to define it; how to measure it Managing for performance: how to define it; how to measure it

People and relationships: your staff your board, your volunteers, your community People and relationships: your staff your board, your volunteers, your community

Developing yourself as a person, as an executive, as a leader Developing yourself as a person, as an executive, as a leader

The Mission Comes First and Your Role as a Leader → Summary: The Action Implications

We hear a great deal these days about leadership, and it’s high time we did.

But, actually, mission comes first.

Non-profit institutions exist for the sake of their mission.

They exist to make a difference in society and in the life of the individual.

They exist for the sake of their mission, and this must never be forgotten.

The first task of the leader is to make sure that everybody sees the mission, hears’ it, lives it.

If you lose sight of your mission, you begin to stumble and it shows very, very fast.

And yet, mission needs to be thought through, needs to be changed.

The basic rationale for the organization may be there for a very long time.

As long as the human race is around, we’ll be miserable sinners.

And as long as the human race is around, we will have sick people who need to be taken care of.

We know that no matter how well a society does, there will be alcoholics, there will be people in trouble with drugs, there will be people who need the Salvation Army to bring compassion to them and a little help, and an attempt to rehabilitate them, and children will have to learn and go to school.

Boys and girls, as they grow up, will need scouting and experiences that form their character, that give them a role model, that give them direction and employ them intelligently so that they learn something.

We will have to look at the mission again and again to think through whether it needs to be refocused because demographics change, because we should abandon something that produces no results and eats up resources, because we have accomplished an objective.

A good example is the school that is largely in crisis because it has achieved its original objective of getting every kind of child to go to school and stay there for years, and now we have to think through what we really do expect of the school.

And this will be, in many ways, quite different from what the schoolmasters through the ages were striving for when nine out of ten kids never had the opportunity of organized schooling.

Therefore, it is vitally important to start out from the outside.

The organization that starts out from the inside and then tries to find places to put its resources is going to fritter itself away.

Above all, it’s going to focus on yesterday.

One looks to the outside for opportunity, for a need.

At the same time, the mission is always long-range.

It needs short-range efforts and very often short-range results.

And yet it starts out with a long-range objective.

There is a wonderful sentence in one of the sermons of that great poet and religious philosopher of the seventeenth century, John Donne: “Never start with tomorrow to reach eternity.

Eternity is not being reached by small steps.”

So we start always with the long range, and then we feed back and say, What do we do today?

“Do” is the critical word.

And that’s the difference between what so often passes for planning in American business and what the Japanese do.

It’s not that they are better planners.

It is that they start out by saying, Where should we be ten years hence?

And we start by saying, What should be the bottom line for the quarter—which contrary to what most people in the United States believe, is higher in Japan than it is in American business, precisely because they start with the long range and feed back.

As did all the companies in this country that have succeeded in staying viable, producing results for long the term.

We have had some amazingly successful long-term companies—the Bell Telephone System, for fifty or sixty years; Sears, Roebuck for sixty years; General Motors, until recently.

They all started out with a very clear long-range concept.

Sears said: Our business is to be the informed and responsible buyer for the American family.

And then one feeds back, and that may lead to very short-term moves—to Sears going into diamonds, for instance, right after World War II when the GIs came back and got married.

But one always starts out with the long term.

This is particularly important for non-profit institutions, precisely because they do not have an immediate bottom line, but also because they are there to serve.

But action is always short term.

So one always has to ask: Is this action step leading us toward our basic long-range goal, or is it going to sidetrack us, going to divert us, going to make us lose sight of what we are here to do?

This is the first question.

But also we need to be result-driven.

We need to ask, Do we get adequate results for our efforts?

Is this their best allocation?

Yes, need is always a reason, but by itself it is not enough.

There also have to be results.

There also has to be something to point at and say, We have not worked in vain.

So we are always looking at programs and projects with the question, Do they produce the right results?

The leader’s job is to make sure the right results are being achieved, the right things are being done.

One has the responsibility to allocate resources, particularly of course in organizations that depend heavily on volunteers, and heavily on donors.

Leadership is accountable for results.

And leadership always asks, Are we really faithful stewards of the talents entrusted to us?

The talents, the gifts of people—the talents, the gifts of money.

Leadership is doing.

It isn’t just thinking great thoughts; it isn’t just charisma; it isn’t play-acting.

It is doing.

And the first imperative of doing is to revise the mission, to refocus it, and to build and organize, and then abandon.

It is asking ourselves whether, knowing what we now know, we would go into this again.

Would we stress it?

Would we pour more resources in, or would we taper off?

That is the first action command for any mission.

It is also the one way of keeping an organization lean and hungry and capable of doing new things.

An old medical proverb says that the body can only take in the new if it eliminates the waste products.

This is therefore the first action requirement: the constant resharpening, the constant refocusing, never really being satisfied.

And the time to do this is when you are successful.

If you wait until things have already started to go down, then it’s very difficult.

It is not impossible to turn around a declining institution, but an ounce of prevention is very much better than a ton of cure in the turnaround situation.

The next thing to do is to think through priorities.

That’s easy to say.

But to act on it is hard because it always involves abandoning things that look very attractive, that people both inside and outside the organization are pushing for.

But if you don’t concentrate your institution’s resources, you are not going to get results.

This may be the ultimate test of leadership: the ability to think through the priority decision and to make it stick.

Leadership is also example.

The leader is visible; he stands for the organization.

He may be totally anonymous the moment he leaves that office and steps into his car to drive home.

But inside the organization, he or she is very visible, and this isn’t just true of the small and local one, it is just as true of the big, national, or worldwide one.

Leaders set examples.

The leaders have to live up to the expectations regarding their behavior.

No matter that the rest of the organization doesn’t do it; the leader represents not only what we are, but, above all, what we know we should be.

So it is a very good rule when you do anything as a leader, to ask yourself, Is that what I want to see tomorrow morning when I look into the mirror?

Is that the kind of person I want to see as my leader?

And if you follow that rule, you will avoid the mistakes that again and again destroy leaders: sexual looseness in an organization that preaches sexual rectitude, petty cheating, all the stupid things we do.

Maybe the individual does them; well, that’s his or her business.

But a leader is not a private person; a leader represents.

And then ask yourself, as a leader, what do I do to set standards in the organization?

What do I do to enable the organization to tackle new challenges, to seize new opportunities, to innovate?

What do I do?

Not what does the organization do?

Take action responsibility.

What are my own first priorities, and what are the organization’s first priorities, what should they be?

These are the action agenda.

These are the things that must be done.

You may think, that’s fine for the CEO, but I’m only a volunteer putting in three hours a week, being a den mother or arranging flowers at a patient’s bedside.

You are a leader.

The exciting thing, the new thing, is that we are creating a society of citizens in the old sense of people who actively work, rather than just passively vote and pay taxes.

We are not doing it in business.

There is a lot of talk of participative management; but there is not much reality to it, and in many ways, there never will be.

The pressures are perhaps too great.

In a country like ours, with almost 250 million people, even a small town has 50,000 inhabitants, and there is not very much a, citizen can actually do.

We could not, even in the smallest town, meaningfully revive the New England town meeting of two hundred years ago, when that New England town had one hundred twenty people or so.

But we are doing exactly this in the non-profit, the service institution, where increasingly there are only leaders.

These are people who are paid and people who are not paid.

In a church there are a very small number of people who are ordained, but one thousand people who work and do major tasks for the church who are not ordained, never will be, never get a penny.

In the Girl Scouts of the U.S.A., there are one hundred volunteers for every paid staff member, and each is doing a responsible task.

We are creating tomorrow’s society of citizens through the non-profit service institution.

And in that society, everybody is a leader, everybody is responsible, everybody acts.

Everybody focuses himself or herself.

Everybody raises the vision, the competence, and the performance of his or her organization.

Therefore, mission and leadership are not just things to read about, to listen to.

They are things to do something about.

Things that you can, and should, convert from good intentions and from knowledge into effective action, not next year, but tomorrow morning.

From Mission to Performance → effective strategies for marketing, innovation, and fund development → Summary: The Action Implications

Strategy converts a non-profit institution’s mission and objectives into performance.

Despite its importance, however, many nonprofits tend to slight strategy.

It seems so obvious to most of them that they are satisfying a need, so clear that everybody who has that need must want the service the non-profit institution has to offer.

One central problem is that too many non-profit managers confuse strategy with a selling effort.

Strategy ends with selling efforts.

It begins with knowing the market—who the customer is, who the customer should be, who the customer might be.

The whole point of strategy is not to look at recipients as people who receive bounty, to whom the non-profit does good.

They are customers who have to be satisfied.

The non-profit institution needs a marketing strategy that integrates the customer and the mission.

An effective non-profit institution also needs strategies to improve all the time and to innovate.

The two overlap.

Nobody can ever quite say where an improvement ends and an innovation begins.

When Frances Hesselbein and the Girl Scouts introduced their new service for five-year-olds, the Daisy Scouts, that was, in one way, just old-fashioned Girl Scouting.

In another way it was a drastic innovation.

And then the non-profit institution needs a strategy to build its donor base.

It needs to develop a donor constituency.

All three of these strategies begin with research and research and more research.

They require organized attempts to find out who the customer is, what is of value to the customer, how the customer buys.

You don’t start out with your product but with the end, which is a satisfied customer.

The most important person to research is the individual who should be the customer, the people who are believers but who have stopped going to church.

Traditionally, businesses have researched their own customers and know, or try to know, as much as possible about them.

But even if you have market leadership, noncustomers always outnumber customers.

The most important knowledge is the potential customer.

The customer who really needs the service, wants the service, but not in the way in which it is available today.

The typical college or university, after twenty years of an enormous number of young people reaching college age, is only now accepting the fact that it has to market the college to high school counselors, to prospective students, to their parents.

Despite a sharp drop in the total number of applicants, colleges that do market effectively have more applications than they can possibly admit.

You would imagine that people would be only too eager for services aimed at helping them prevent a heart attack, or recover from it.

Yes, they are, but only if the service fits them—their age, their weight.

They manage their own life and their own health.

This understanding of the importance of strategy is particularly crucial to non-profit managers when it comes to their donors.

The typical non-profit institution still goes around telling donors, “Here is the need.”

But the ones that get results—the ones that attract and build a fund constituency—say, “This is what you need.

These are the results.

This is what we do for you.”

They look upon the donor as a customer.

This is the essence of a strategy: it always starts out with the other side.

Even thousands of years ago, the beginning of wisdom in military strategy was to start out with the enemy and not with your own troops.

The next step in non-profit strategy (as in military strategy) is the training of your own people.

Everyone in the hospital must be patient-conscious.

That’s a training job—not just preaching.

It isn’t attitude, it’s behavior.

In fact, we have learned that attitude training is not very effective.

The way to train people is behaviorally: This is what you do.

With that kind of specific training, even hospital workers who are very far away from the customer—the billing office, the janitorial workers—do things that satisfy the customers: the physicians, the patients.

In non-profit management, training doesn’t apply only to the employees; training volunteers may be even more essential, especially in an organization in which volunteers are the interface with the customers, with the public.

When it comes to introducing something new, when it comes to innovation, non-profit strategy requires careful thought and planning: where to start and with whom.

Start with people who want the new to succeed.

Don’t try to have everybody in the organization run with the new first.

That route always gets into trouble.

Look for a target of opportunity, for somebody in the organization who wants the new, who is convinced of it, who is committed to it.

The strategy in innovation is to think through this process at the start, so that you can identify somebody willing to work hard at making the new successful, and somebody whose success then becomes a multiplier in the organization.

The worst thing in strategy is to introduce something with great fanfare and great hope that it is going to change the world, and five years later say, “Well, it’s doing all right.

It’s a little specialty.”

That’s failure.

That’s misallocation of resources.

Knowing the customer also enables the non-profit organization—whether it’s the church, the synagogue, the Scouts, a hospital, a college—to know what results to expect.

It is important to define goals and know what realistically should work.

What are we trying to do?

This college is trying to get in so many applicants, of what quality, so that it can maintain its size and quality.

Then one can feed back from results.

Then one can say, “Well, we are doing quite well here, but not really well over there.

Let’s put in a little more effort.”

Or, “We need a stronger person in charge.”

Or, “We need to offer something additional that will bring in the kind of students we need.”

Strategy also demands that the non-profit institution organize itself to abandon what no longer works, what no longer contributes, what no longer serves.

A church must get out of the singles ministry if it doesn’t have the right person to run it and cannot guarantee a quality service.

The American Heart Association must be willing to play down older people as potential donors because to people over seventy-five or eighty, death by heart attack is not the worst of all possible ways to go.

That’s abandonment.

If you don’t build it in, you’ll soon overload your organization and put good resources where the results don’t follow.

The question always before the non-profit executive is: What should our service do for the customer that is of importance to that customer?

Then think through how the service should be structured, be offered, be staffed.

End up with nuts and bolts: What to do, when to do, where to do.

And most importantly, who is to do it?

Strategy begins with the mission.

It leads to a work plan.

It ends with the right tools—a kit, say for volunteers, which tells them who to call on, what to say, and how much money to get.

Without that kit, there is no strategy.

The last thing to say about strategy is that it exploits opportunity, the right moment.

Greek theologians called it Kairos, the point when the new is received.

Most of the needs non-profit institutions fill are likely to be there forever in one form or another; they are parts of the human condition.

But the need presents itself in a specific form, and it is the function of research to find out, at this time, what that form is.

Especially for the ones who should be customers but aren’t because the service is not available in a form that serves them.

Ask: “Is this something that fits our strengths?

Can we develop the service that satisfies?”

Then comes that third element, the right moment to seize the opportunity by the forelock, to run with success.

Strategy commits the non-profit executive and the organization to action.

Its essence is action-putting together mission, objectives, the market—and the right moment.

The tests of strategy are results.

It begins with needs and ends with satisfactions.

For this you need to know what the satisfactions should be for your customers: the parishioners in your church, the sick in your hospital, the boys and girls in your Scout troops, and the volunteers who lead them.

What is really meaningful to them?

Non-profit people must respect their customers and their donors enough to listen to their values and understand their satisfactions.

They do not impose the executive’s or the organization’s own views and egos on those they serve.

Managing for Performance → how to define it; how to measure it → Summary: The Action Implications

Performance is the ultimate test of any institution.

Every nonprofit institution exists for the sake of performance in changing people and society.

Yet, performance is also one of the truly difficult areas for the executive in the non-profit institution.

I'm always being asked what the differences are between business and non-profit institutions.

There are few, but they are important.

Perhaps the most important is in the performance area.

Businesses usually define performance too narrowly—as the financial bottom line.

If that's all you have as a performance measurement and performance goal in the business, you are not likely to do well or survive very long.

It's too narrow.

But it's very specific and concrete.

You don't have to argue about whether we are doing better because results within terms of profitability or market standing or innovation or cash flow are easily quantifiable and very hard to ignore.

In a non-profit organization, there is no such bottom line.

But there is also a temptation to downplay results.

There is the temptation to say: We are serving in a good cause.

We are doing the Lord's work.

Or we are doing something to make life a little better for people and that's a result in itself.

That is not enough.

If a business wastes its resources on non-results, by and large it loses its own money.

In a non-profit institution, though, it's somebody else's money—the donors' money.

Service organizations are accountable to donors, accountable for putting the money where the results are, and for performance.

So, this is an area that needs special emphasis for non-profit executives.

Good intentions only pave the way to Hell.

Nonetheless, non-profit institutions find it very hard to answer the question: What, then, are "results" in our institution?

It can be done, however.

Indeed, results can even be quantified—at least some of them.

The Salvation Army is fundamentally a religious organization.

Nevertheless, it knows the percentage of alcoholics it restores to mental and physical health and the percentage of criminals it rehabilitates.

It is highly quantitative.

For many organizations in the non-profit sector, to be specific about results is still odious.

They still believe their work can only be judged by quality—if at all.

Some of them still quite openly sneer at any attempt to ask: "How well are you doing in terms of the resources you spent?

What return do you get?"

One sometimes has to remind them of the Parable of the Talents in the New Testament: Our job is to invest the resources we have—people and money—where the returns are manifold.

And that's a quantitative term.

There are different kinds of results.

First, you have immediate results.

Then, you have the long-term job of building on those first results.

Maybe it's not easy to define precisely what results you have, but it's got to be done in such a way that one can ask: "Are we getting better?

Are we improving?"

And: "Do we put our resources where the results are?"

We need to remind ourselves again and again that the results of a non-profit institution are always outside the organization, not inside.

Results for the Salvation Army are among the alcoholics and the prostitutes and the hungry.

Results for the schoolteacher are kids who learn.

And can good intentions and hopes ever justify non-results?

A few Jesuit Fathers managed to sneak into China as missionaries in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

They were brilliant men; they endured persecution and hardships and dangers.

They worked terribly hard and they stayed in China year after year after year—with no results.

Yet they kept on hoping, kept on trying to find a few people who would be receptive to Christianity.

In the process they became very respected men in China—astronomers, mathematicians, painters.

But it was a misallocation of very scarce resources to work that produced no results.

In Heaven there is joy over one sinner who repents.

But in Heaven, there is also, I am sure, joy over the right allocation of resources to the mission, to the goals, to results.

And the Jesuits long ago stopped wasting brilliant members of their order on hopes.

One starts with the mission, and that is exceedingly important.

What do you want to be remembered for as an organization—but also as an individual?

The mission is something that transcends today, but guides today, informs today.

The moment we lose sight of the mission, we begin to stray, we waste resources.

From the mission, one goes to very concrete goals.

Only when a non-profit's key performance areas are defined can it really set goals.

Only then can the non-profit ask: "Are we doing what we are supposed to be doing?

Is it still the right activity?

Does it still serve a need?"

And, above all, "Do we still produce results that are sufficiently outstanding, sufficiently different for us to justify putting our talents to use in that area?"

Then, you can do the next important thing, which is every so often to ask: "Are we still in the right areas?

Should we change?

Should we abandon?"

The Salvation Army began, 128 years ago, by building shelters for the streetwalkers of London.

Nobody cared then about those unfortunate women, any number of whom were poor country girls adrift in the big city.

The Salvation Army still has a program to look after prostitutes.

But it has given up providing hostels to shelter innocent and ignorant country girls.

Those country girls now come equipped with employable skills, and they are by no means ignorant anymore; they are just as sophisticated as anybody else.

So, the Salvation Army abandoned this mission even though it was the original activity.

One needs to define performance for each of the non-profit's key areas.

Think through the key performance areas for this organization—not for an organization—for this one, and focus on each of them.

In a non-profit institution, where people want to serve a cause, you always have the challenge which Max De Pree discussed in his earlier interview: getting people to perform so that they grow on their own terms.

They are then accomplished and fulfilled, and that makes its way down to the performance of the organization.

This is essential.

Results are achieved, too, by concentration, not by splintering.

That enormous organization the Salvation Army concentrates on only four or five programs.

Its executives have the courage to say, "This is not for us.

Other people do it better."

Or, "This is not really what we are good at."

Or, "This is not where we can make the greatest contribution.

It does not really fit the strength we have."

One of the most important things for a non-profit executive to be able to acknowledge is that "there we are not competent; we can only do harm.

Need alone does not justify our moving in.

We must match our strength, our mission, our concentration, our value."

Good intentions, good policies, good decisions must turn into effective actions.

The statement, "This is what we are here for," must eventually become the statement, "This is how we do it.

This is the time span in which we do it.

This is who is accountable.

This is, in other words, the work for which we are responsible."

Effective organizations take it for granted that work isn't being done by having a lovely plan.

Work isn't being done by a magnificent statement of policy.

Work is only done when it's done.

Done by people.

By people with a deadline.

By people who are trained.

By people who are monitored and evaluated.

By people who hold themselves responsible for results.

The ultimate question, which I think people in the non-profit organization should ask again and again and again, both of themselves and of the institution, is: "What should I hold myself accountable for by way of contribution and results?

What should this institution hold itself accountable for by way of contribution and results?

What should both this institution and I be remembered for?"

People and Relationships → your staff, your board, your volunteers, your community → Summary: The Action Implications

In no area are the differences greater between businesses and nonprofit institutions than in managing people and relationships.

Although successful business executives have learned that workers are not entirely motivated by paychecks or promotions—they need more—the need is even greater in non-profit institutions.

Even paid staff in these organizations need achievement, the satisfaction of service, or they become alienated and even hostile.

After all, what’s the point of working in a non-profit institution if one doesn’t make a clear contribution?

Furthermore, there are people working in non-profit organizations that businesses have no experience dealing with.

They are called “volunteers,” though that no longer is quite the right word.

They are different from the paid workers in a non-profit only in that they are not paid.

There is less and less difference between the work they do and that done by the paid workers—in many cases it is now identical—and the volunteers are becoming increasingly important to non-profit organizations.

Not only is the number of volunteers increasing.

They are taking on more and more leadership functions.

This trend is likely to continue as we have many more older people in our society who are capable of working physically and mentally and are also eager to stay active, to stay involved, to contribute.

Thus, non-profit institutions will be serving their specific missions, but they also will increasingly be the organizations through which we make citizenship operational and effective.

Altogether, the non-profit executive deals with a greater variety of stakeholders and constituencies than the average business executive.

The non-profit institution’s relationship with its donors, for instance, is not known to business enterprises.

A company’s shareholders and customers have completely different expectations from donors.

The non-profit board also plays a very different role from the company board.

It is more active and, at the same time, more of a resource if managed properly—and more of a problem if not managed properly.

The problems can be most pronounced when the board is not selected by the institution itself but is elected—as co-op boards and most school boards are elected—by outside constituencies which may be critics of the institution.

Because of the complexity of relationships for the non-profit executive, it is important to understand and apply what we know about the management of people and the management of relationships.

And we know a good deal.

People require clear assignments.

That’s true of volunteers; that’s true of the board; that’s true of the employed staff.

They need to know what the institution expects of them.

But the responsibility for developing the work plan, the job description, and the assignment should always be on the people who do the work.

The non-profit executive must work both with employed staff and with volunteers so that they can think through their contribution, spell it out clearly, and evolve by joint discussion a specific work plan, with specific goals and specific deadlines.

The less control you have over people in the old-fashioned sense by fear, disciplining them, demoting them, or not promoting them, the more important it is that they have a clear assignment for which they themselves take responsibility.

The non-profit must be information-based.

It must be structured around information that flows up from the individuals doing the work to the people at the top—the ones who are, in the end, accountable—and around information flowing down, too.

This flow of information is essential because a non-profit organization has to be a learning organization.

Emphasis in managing people should always be on performance.

But, especially for a non-profit, it must also be compassionate.

People work in non-profits because they believe in the cause.

They owe performance, and the executive owes them compassion.

People given a second chance usually come through.

If people try, give them a second chance.

If people try again and they still do not perform, they may be in the wrong spot.

Then one asks: Where should he or she be?

Perhaps in another position in the organization—or perhaps elsewhere, in another organization.

But, if a person doesn’t try at all, encourage him or her as soon as possible to go to work. for the competition.

A recurring problem for non-profit organizations such as churches, hospitals, and the Scouts are the people who volunteer because they are profoundly lonely.

When it works, these volunteers can do a great deal for the organization—and the organization, by giving them a community, gives even more back to them.

But sometimes these people for psychological or emotional reasons simply cannot work with other people; they are noisy, intrusive, abrasive, rude.

Non-profit executives have to face up to that reality.

Perhaps there is a job, in some corner, which they can do.

But if there isn’t, they must be asked to leave.

The alternative is that the executive, and all those who have to work with the person, lose capacity to contribute.

The non-profit board is both the tool of the non-profit chief executive and the chief executive’s conscience.

For this relationship to prosper, the chief executive must develop a clear work plan for the board.

A non-profit executive can—and must—manage even a board that is elected by outside (sometimes critical) forces and that cannot be dismissed by the professional executive.

But, to be productive, the board must be informed.

The worst thing a chief executive can do is try to hide things from the board, play little games, focus on finding a friend or two on the board and ignore building an overall relationship.

That’s always a temptation.

But the executive who yields to it can be guaranteed to be out on his or her ear within a year or two.

Everyone in the non-profit institution, whether chief executive or volunteer foot soldier, needs first to think through his or her own assignment.

What should this institution hold me accountable for?

The next responsibility is to make sure that the people with whom you work and on whom you depend understand what you intend to concentrate on, and what you should be held accountable for.

Next are the learning and teaching responsibilities: What do I have to learn?

What does this organization have to learn?

Not in five years—but now, over the next few months.

If you are an executive in a non-profit institution, make sure you sit down next week with your key people and say, “I am not here to tell you anything.

I am here to listen.

What do I need to know about you and your aspirations for yourselves—and for this organization of ours?

Where do you see opportunities that we don’t seem to be taking advantage of?

Where do you see threats?

What are we doing well?

What are we doing badly?

What improvements do we have to make?”

Make sure to listen—but also make sure to take action on what you hear and learn.

Ask every one of the people who report to you or with whom you work: “What am I doing that helps you with your work?

What am I doing that hampers you?”

Act on what they tell you.

If the complaint is, for instance, that you don’t give information unless asked, make sure that the required information goes out every Friday, or whenever.

If they say they don’t know how they are doing, build feedback into your system.

They have their jobs to do, and the non-profit executive’s job is to enable them to do it, successfully and satisfactorily.

What you may need most, along with your associates, is clear information about the results of your organization’s work.

We go out and solicit money by talking needs.

That’s fine.

But both donors and people who work for a non-profit inevitably ask—What are the results?

No executive should respond with generalities.

The effective non-profit executive finally takes responsibility for making it easy for people to do their work, easy to have results, easy to enjoy their work.

It’s not enough for them, or for you, that they serve a good cause.

The executive’s job is to make sure that they get results.

Part 5 Summary: Developing yourself — as a person, as an executive, as a leader → The Action Implications

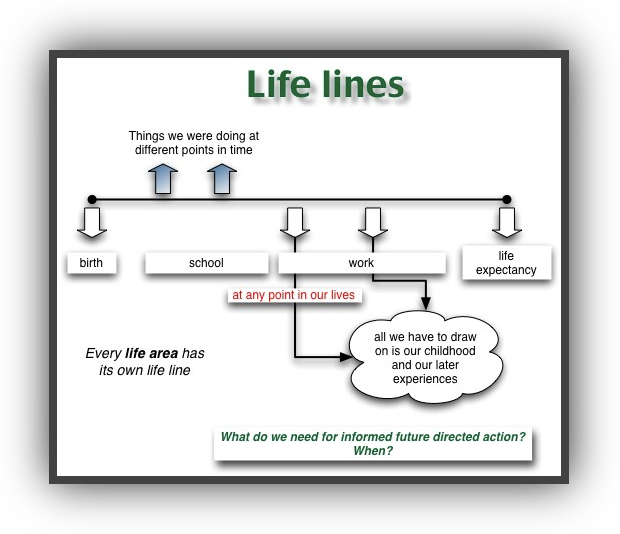

The best way for me to start this summary on self-development is to tell you about the man who first made me aware of what that means as a lifelong process.

More about Peter Drucker

He was a Jewish rabbi whom I first met in the early 1950s on a mountain trail.

We became hiking companions for many years because we both spent vacations in the same summer resort and liked hiking.

Joshua Abrams had been in law school when World War II broke out, went into the Navy and was badly wounded.

In fact, he never fully recovered, and the injuries eventually caused his death thirty-five years later.

He went into a seminary when he came out of the service and, when I first met him, he had just begun to build—from scratch—a synagogue and Jewish community center in a major Midwestern city.

Building: human community, donors, physical structures

Just ten years later it was one of the largest Reformed Jewish synagogues in the country, with four to five thousand members.

So, I was very surprised on a walk one day when he said, “By the way, Peter, I’ve decided to leave the synagogue and start all over again.”

I looked at him, clearly without understanding, and he continued, “I don’t learn anything anymore.”

Knowledge exists only in application

A year later, he told me he had decided to go into youth ministry and take over the chaplainship at a major Midwestern university.

This was about 1964-65.

Joshua explained:

“I’m still young enough so that I understand what troubles the kids and I’m old enough to have experience with most of the things that they are going through.

They’re going to be in trouble.”

Sure enough, the student unrest started not too long afterward and my friend was a tower of strength.

Vietnam War

Vietnam War PBS

Through the years I’ve met people who say, “I understand you know Josh Abrams?

He saved my life when I was twenty years old and about to destroy myself by going into drugs … or by doing this, that or the other stupid thing.”

Then, around 1973-74, Josh surprised me again during one of our walks:

“I think I’ve done all I can do as a university chaplain.

I’m no longer young enough to be in tune with the kids.

I’ve been thinking about it and have decided that the need now is for a ministry for old people.

That’s where the population growth is.”

He quit the university a year or two later, moved to one of the retirement cities in Arizona, and started all over again building from scratch.

Building: everything needed

to get him from scratch

to where he wanted to go

By the time he died, his new community of retired people was three to four thousand strong.

He looked for people who were lonely, who had lost their spouses, who were sick, and he not only brought them spiritual comfort but helped meet their physical needs as well as he could.

Joshua was the first person who explained something to me that I have, in turn, repeated to many, many people:

“You are responsible for allocating

your life.

Nobody else will do it for you.”

A trail head

And the pattern of his life makes clear

that when we talk of self-development,

we mean two things:

developing the person, and

developing the skill, competence, and ability to contribute.

These are two quite different tasks.

Developing yourself — as a person —

begins by serving,

by striving toward an idea

outside of yourself — not by leading.

sidebar begins ↓

Managing Oneself —

a revolution in human affairs

Three stonecutters

Awareness ::: What’s your meta-system?

… you may believe that feelings and values are

the most important things in life. You are right.

That is why thinking is so very important. continue

How can the individual survive?

Drucker’s life as a knowledge worker

What do you want to be remembered for?

Citizenship through the social sector

Where Right Becomes Wrong

Idea seeds here and here

Every single social and global issue of our day is a

business opportunity in disguise — here, here and here

Aiming high

Willing engagement is necessary

Extreme caution is needed here: see

How To Guarantee Non-Performance

and What Results Should You Expect?: A User's Guide to MBO

Conditions for survival

Drucker and Me

main brainroad continues ↓

Leaders are not born,

nor are they made —

they are self-made.

To do this, a person needs focus.

Michael Kami, our leading authority on business strategy today, draws a square on the blackboard and asks:

“Tell me what to put in there.

Jesus?

Or money?

I can help you develop a strategy for either one,

but you have to decide

which is the master.”

I do it by asking people

what they want to be remembered for —

that’s “the beginning of adulthood,” according to St. Augustine.

The answer changes as we mature—as it should.

and with changes in the world

But unless that question is asked,

a person works without focus,

without direction, and, as a result,

does not develop.

You start by developing your own strengths, adding skills and putting them to productive work.

Previous link leads to Managing Oneself

There is much a boss can do to contribute to this development.

But no matter how much a boss drives you — or ignores you —

ultimately it is the individual’s own responsibility

to work on his or her own development.

Developing your strengths does not mean ignoring your weaknesses.

On the contrary, one is always conscious of them.

But one can only overcome weakness by developing strengths.

Don’t take shortcuts.

You don’t have to be a perfectionist but you certainly should refuse to accept your own shoddy work.

Above all, workmanship builds your own self-respect as it builds your own competence.

Next, you work on the TASKS (that need) to be done, the opportunities to be explored:

And you start with THE (MAJOR / highest conceptual) task, not with yourself.

He is referring to the concept of TASK at the highest conceptual level and not tasks in ordinary daily life

Designing one’s life over time is a major task

Moving people from where they live to where they work is a major task

Try a page search for “task” on the current page and here

«§§§»

Achievement comes from

matching

need and opportunity

on the outside (of yourself)

with competence and strength

on the inside (of yourself).

The two ↑ have to meet

— and the two have to match.

«§§§»

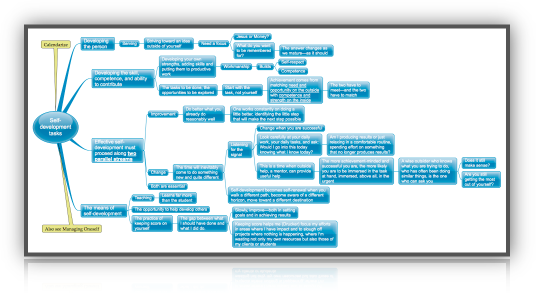

Effective self-development

must proceed along

two parallel streams.

One is improvement—to do better what you already do reasonably well.

The second is change—to do something different.

The danger of too much planning

Most mistakes in thinking

are mistakes in perception

Yes, I will do that, but

The Second Curve

Both are essential.

It is a mistake to focus only on change and forget what you already do well.

One works constantly on doing a little better, identifying the little step that will make the next step possible.

But it is equally foolish to focus only on improvement and forget that the time will inevitably come to do something new and quite different.

sidebar ↓

Drucker’s life as a knowledge worker

Important for life 2.0

The Individual In Entrepreneurial Society

Make Judgement Operational

main brainroad continues ↓

Listening for the signal (examples: 1 and 2) that it is time to change is an essential skill for self-development.

Change when you are successful—not when you’re in trouble.

Look carefully at your daily work, your daily tasks, and ask:

“Would I go into this today knowing what I know today?

Am I producing results or just relaxing in a comfortable routine, spending effort on something that no longer produces results?”

Self-development

becomes self-renewal

when you walk a different path,

become aware of a different horizon,

move toward a different destination.

This is a time when outside help, a mentor, can provide useful help.

The more achievement-minded and successful you are, the more likely you are to be immersed in the task at hand, immersed, above all, in the urgent.

A wise outsider who knows what you are trying to do, who has often been doing similar things, is the one who can ask you:

“Does it still make sense?

Are you still getting the most out of yourself?”

The means for self-development are not obscure.

Many achievers have discovered that teaching is one of the most successful tools.

The teacher usually learns far more than the student.

Not everybody is in a situation where the opportunity to teach opens up, nor is everyone good at teaching or enjoying it.

But everyone has an associated opportunity—the opportunity to help develop others.

Everyone who has sat down with subordinates or associates in an honest effort to improve their performance and results understands what a potent tool the process is for self-development.

Probably the best of the nuts and bolts of self-development is the practice of keeping score on yourself.

It’s also the best lesson in humility, as I can tell you from personal experience.

It is always painful for me to see how great the gap is between what I should have done and what I did do.

But, slowly, I improve—both in setting goals and in achieving results.

Keeping score helps me focus my efforts in areas where I have impact and to slough off projects where nothing is happening, where I’m wasting not only my own resources but also those of my clients or students.

Self-development is neither a philosophy nor good intentions.

Self-renewal is not a warm glow.

Both are action.

You become a bigger person, yes; but, most of all, you become a more effective and committed person.

Larger view ↑

So, I conclude by asking you to ask yourself, what will you do tomorrow as a result of reading this book?

And what will you stop doing?

Just reading is not enough

The chapters on “You are responsible” and “What do you want to be remembered for” — above — contain useful action areas. You can search for those phrases in the book notes outline and part 5 PDF

Further exploration

“Fortune favors the prepared ↑ ↓ mind” continue

A Century of Social Transformation A Century of Social Transformation

Landmarks of Tomorrow Landmarks of Tomorrow

Men of high effectiveness are conspicuous by their absence in executive jobs Men of high effectiveness are conspicuous by their absence in executive jobs

Post-Capitalist executive interview Post-Capitalist executive interview

Take responsibility for your career Take responsibility for your career

Drucker: My life as a knowledge worker Drucker: My life as a knowledge worker

Ten Principles for Life II Ten Principles for Life II

The Wisdom of Peter Drucker The Wisdom of Peter Drucker

The World is Full of Options The World is Full of Options

What Makes An Effective Executive? What Makes An Effective Executive?

The second half of your life The second half of your life

What executives should remember What executives should remember

Peter Drucker On Leadership Peter Drucker On Leadership

The memo — navigating unimagined futures The memo — navigating unimagined futures

Managing Service Institutions in the Society of Organizations

From Chapter 12 of Management, Revised Edition

Amazon Links: Management Rev Ed and Management Cases, Revised Edition and Management Cases, Revised Edition

Business enterprise is only one of the institutions of modern society, and business managers are by no means our only managers.

Service institutions are equally institutions and, therefore, equally in need of management.

Some of the most familiar of these institutions are government agencies, the armed services, schools, colleges, universities, research laboratories, hospitals and other health-care institutions, unions, professional practices such as the large law firm, and professional, industry, and trade associations.

They all have people who are paid for doing the management job, even though they may be called administrators, commanders, directors, or executives, rather than managers.

The Multi-Institutional Society

Public-service institutions are supported by the economic surplus produced by economic activity.

They are social overhead.

The growth of the public service institution in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries is the best testimonial to the success of business in discharging its economic task—producing economic surplus.

Yet, unlike the early nineteenth-century university, the service institutions are not a luxury or an ornament.

They are essentials of a modern society.

They have to perform if society and business are to function.

These service institutions are the main expense of a modern society.

Approximately half of the gross national product of the United States (and of most of the other developed countries) is spent on public-service institutions.

Every citizen in the developed, industrialized, urbanized societies depends for survival on the performance of the public-service institutions.

These institutions also embody the values of developed societies.

Education, health care, knowledge, and mobility—not just more food, clothing, and shelter—are the fruits of our society's increased economic capacities and productivity.

Yet the evidence for performance in the service institutions is not impressive, let alone overwhelming.

Colleges, hospitals, and universities have grown larger than an earlier generation would have dreamed possible.

Their budgets have grown even faster.

Yet everywhere they are in crisis.

A generation or two ago their performance was taken for granted.

Today they are attacked on all sides for lack of performance.

Services that the nineteenth century managed successfully with little apparent effort—the postal service, for instance, or the railroads—are today deep in the red and require enormous subsidies.

National and local government agencies are constantly being reorganized for efficiency.

Yet in every country citizens complain loudly of growing bureaucracy in government.

What they mean is that the government agency is being run more for the convenience of its employees than for contribution and performance.

This is mismanagement.

Are Service Institutions Managed?

The service institutions themselves have become "management conscious."

Increasingly they turn to business to learn management.

In all service institutions, manager development, management by objectives, and many other concepts and tools of business management are now common.

This is a healthy sign, but it does not mean that the service institutions understand the problems of managing themselves.

It only means that they begin to realize that at present they are not being managed.

But Are They Manageable?

There is another and very different response to the performance crisis of the service institutions.

A growing number of critics have come to the conclusion that service institutions are inherently unmanageable and incapable of performance.

Some go so far as to suggest that they should, therefore, be dissolved.

But there is not the slightest evidence that today's society is willing to do without the contributions the service institutions provide.

The people who most vocally attack the shortcomings of the hospitals want more and better health care.

Those who criticize public schools want better, not less, education.

The voters bitterest about government bureaucracy vote for more government programs.

We have no choice but to learn to manage the public-service institutions for performance.

And they can be managed for performance.

Managing Public-Service Institutions For Performance

Different classes of service institutions need different structures.

But all of them need first to impose on themselves discipline of the kind imposed by leaders of the institutions in the examples in the previous chapters.

This work involves

attention-directing and

mental patterns

They need to define "what our business is and what it should be." They need to define "what our business is and what it should be."

See "The Theory of the Business" in chapter 8 of Management, Revised Edition and The Five Most Important Questions You Will Ever Ask About Your Organization (converts intentions into action)

They need to bring alternative definitions into the open and consider them carefully. They need to bring alternative definitions into the open and consider them carefully.

They should perhaps even work out some balance between the different and conflicting definitions of mission (as did the presidents of the emerging American universities—see later in this chapter).

They must derive clear objectives and goals from their definition of function and mission. They must derive clear objectives and goals from their definition of function and mission.

They then must set priorities that enable them to select targets, to set standards of accomplishment and performance—that is, to define the minimum acceptable results, to set deadlines, to go to work on results, and to make someone accountable for results. They then must set priorities that enable them to select targets, to set standards of accomplishment and performance—that is, to define the minimum acceptable results, to set deadlines, to go to work on results, and to make someone accountable for results.

They must define measurements of performance—customer-satisfaction measurements for the performance of Medicare services, or the number of households supplied with electric power (a quantity much easier to measure). They must define measurements of performance—customer-satisfaction measurements for the performance of Medicare services, or the number of households supplied with electric power (a quantity much easier to measure).

They must use these measurements to feed back on their efforts. They must use these measurements to feed back on their efforts.

That is, they must build self-control by results into their system.

Finally, they need an organized review of objectives and results, to weed out those objectives that no longer serve a purpose or have proven unattainable. Finally, they need an organized review of objectives and results, to weed out those objectives that no longer serve a purpose or have proven unattainable.

They need to identify unsatisfactory performance and activities that are outdated or unproductive, or both.

And they need a mechanism for dropping such activities rather than wasting money and human energies where the results are poor.

The last requirement may be the most important one.

Without a market test, the service institution lacks the built-in discipline that forces a business eventually to abandon yesterday—or else go bankrupt.

Assessing and abandoning low-performance activities in service institutions, outside and inside business, would be the most painful but also the most beneficial improvement.

As the examples have shown, no success is "forever."

Yet it is even more difficult to abandon yesterday's success than it is to reappraise a failure.

A once-successful project gains an air of success that outlasts the project's real usefulness and disguises its failings.

In a service institution particularly, yesterday's success becomes "policy," "virtue," "conviction," if not holy writ.

The institution must impose on itself the discipline of thinking through its mission, its objectives, and its priorities, and of building in feedback control from results and performance on policies, priorities, and action.

Otherwise, it will gradually become less and less effective.

We are in such a welfare mess today in the United States largely because the welfare program of the 1930s was such a success.

We could not abandon it and, instead, misapplied it to the radically different problem of the inner-city poor.

To make service institutions perform, it should by now be clear, does not require great leaders.

It requires a system.

The essentials of this system are not too different from the essentials of performance in a business enterprise, but the application will be quite different.

The service institutions are not businesses; performance means something quite different in them.

The applications of the essentials differ greatly for different service institutions.

As our later examples will show, there are at least three different kinds of service institutions—institutions that are not paid for performance and results, but for efforts and programs.

How to guarantee non-performance How to guarantee non-performance

Management by Objectives — a user’s guide Management by Objectives — a user’s guide

Entrepreneurship in the Public-Service Institution

From Chapter 16 of Management, Revised Edition

Public-service institutions—such as government agencies, labor unions, churches, universities and schools, hospitals, community and charitable organizations, professional and trade associations, and the like—need to be entrepreneurial and innovative fully as much as any business does.

Indeed, they may need it more.

The rapid changes in today’s society, technology, and economy are simultaneously an even greater threat to them and an even greater opportunity.

Yet public-service institutions find it far more difficult to innovate than does even the most “bureaucratic” company.

The “existing” seems to be even more of an obstacle for them.

To be sure, every service institution likes to get bigger.

In the absence of a profit test, size is the one criterion of success for a service institution, and growth a goal in itself.

And then, of course, there is always so much more that needs to be done.

But stopping what has “always been done” and doing something new are equally anathema to service institutions, or at least excruciatingly painful to them.

Most innovations in public-service institutions are imposed on them either by outsiders or by catastrophe.

The modern university, for instance, was created by a total outsider, the Prussian diplomat Wilhelm von Humboldt.

He founded the University of Berlin in 1809, when the traditional university of the seventeenth and eighteenth century had been all but completely destroyed by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars.

Sixty years later, the modern American university came into being, when the country’s traditional colleges and universities were dying and could no longer attract students.

Similarly, all basic innovations in the military in the twentieth century, whether in structure or in strategy, have followed on ignominious malfunction or crushing defeat:

the reorganization of the American army and of its strategy by a New York lawyer, Elihu Root, Teddy Roosevelt’s secretary of war, after its disgraceful performance in the Spanish-American War;

the reorganization, a few years later, of the British army and its strategy by Secretary of War Lord Haldane, another civilian, after the equally disgraceful performance of the British in the Boer War; and

the rethinking of the German army’s structure and strategy after the defeat of World War I.

And in government, one of the greatest examples of innovative thinking in recent political history, America’s New Deal of 1933-1936, was triggered by a Depression so severe as to almost unravel the country’s social fabric.

Critics of bureaucracy blame the resistance of public-service institutions to entrepreneurship and innovation on “timid bureaucrats,” on time-servers who “have never met a payroll,” or on “power-hungry politicians.”

It is a very old litany—in fact, it was already hoary when Machiavelli chanted it almost 500 years ago.

The only thing that changes is who intones it.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, it was the slogan of the so-called liberals and now it is the slogan of the so-called neoconservatives.

Alas, things are not that simple, and “better people” that perennial panacea of reformists—is a mirage.

The most entrepreneurial, innovative people behave like the worst time-serving bureaucrat or power-hungry politician six months after they have taken over the management of a public-service institution, particularly if it is a government agency.

The forces that impede entrepreneurship and innovation in a public-service institution are inherent in it, integral to it, inseparable from it.

The best proof of this are the internal staff services in businesses, which are, in effect, the “public-service institutions” within business corporations.

These are typically headed by people who have come out of operations and have proven their capacity to perform in competitive markets.

And yet, the internal staff services are not notorious as innovators.

They are good at building empires—and they always want to do more of the same.

They resist abandoning anything they are doing.

But they rarely innovate once they have been established.

There are three main reasons why the existing enterprise presents so much more of an obstacle to innovation in the public-service institution than it does in the typical business enterprise.

First, the public-service institution is based on a “budget” rather than on being paid out of its results.

It is paid for its efforts and out of funds somebody else has earned, whether the taxpayer, the donors of a charitable organization, or the company for which a human resource department or the marketing services staff work.

The more efforts the public-service institution engages in, the greater its budget will be.

And “success” in the public-service institution is defined by getting a larger budget rather than obtaining results.

Any attempt to slough off activities and efforts, therefore, diminishes the public-service institution.

It causes it to lose stature and prestige.

Failure cannot be acknowledged.

Worse still, the fact that an objective has been attained cannot be admitted.

A service institution is dependent on a multitude of constituents.

In a business that sells its products on the market, one constituent, the consumer, eventually overrides all the others.

A business needs only a very small share of a small market to be successful.

Then it can satisfy the other constituents, whether they are shareholders, workers, the community, and so on.

But precisely because public-service institutions—and that includes the staff activities within a business corporation—have no “results” out of which they are being paid, any constituent, no matter how marginal, has, in effect, a veto power.

A public-service institution has to satisfy everyone; certainly, it cannot afford to alienate anyone.

The moment a service institution starts an activity, it acquires a “constituency,” which then refuses to have the program abolished or even significantly modified.

But anything new is always controversial.

This means that it is opposed by existing constituencies without having formed, as yet, a constituency of its own to support it.

The most important reason, however, is that public-service institutions exist, after all, to “do good.”

This means that they tend to see their mission as a moral absolute rather than as economic and subject to a cost-benefit calculus.

Economics always seeks a different allocation of the same resources to obtain a higher yield.

Everything economic is therefore relative.

In the public-service institution, there is no such thing as a higher yield.

If one is “doing good,” then there is no “better.”

Indeed, failure to attain objectives in the quest for a “good” only means that efforts need to be redoubled.

The forces of evil must be far more powerful than expected and need to be fought even harder.

For thousands of years the preachers of all sorts of religions have held forth against the “sins of the flesh.”

Their success has been limited to say the least.

But this is no argument as far as the preachers are concerned.

It does not persuade them to devote their considerable talents to pursuits in which results may be more easily attainable.

On the contrary, it only proves that their efforts need to be redoubled.

Avoiding the “sins of the flesh” is clearly a “moral good,” and thus an absolute, which does not admit to any cost-benefit calculation.