About time

“To know something,

to really understand something important,

one must look at it from sixteen different angles.

People are perceptually slow,

and there is no shortcut to understanding;

it takes a great deal of time.” continue

About management

and “Nothing ever changes here …

“I’ve seen a great many people

who are exceedingly good

at execution, but

exceedingly poor

at picking the important things.

They are magnificent at getting

the unimportant things done.

They have an impressive record

of achievement on trivial matters” — PFD

Aiming high

“Concentration — that is, the courage to impose on time and events

his own decision as to what really matters

and comes first — is the executive’s only hope

of becoming the master of time and events

instead of their whipping boy” — The Effective Executive

Tomorrow always arrives and

it is always different

… Effective executives know that

time is THE limiting factor.

The output limits of any process are set by the scarcest resource.

In the process we call “accomplishment,” this is time.

Time is also a unique resource.

Of the other major resources, money is actually quite plentiful.

We long ago should have learned that it is the demand for capital, rather than the supply thereof, which sets the limit to economic growth and activity.

People—the third limiting resource—one can hire, though one can rarely hire enough good people.

But one cannot rent, hire, buy, or otherwise obtain more time.

The supply of time is totally inelastic.

No matter how high the demand, the supply will not go up.

There is no price for it and no marginal utility curve for it.

Moreover, time is totally perishable and cannot be stored.

Yesterday's time is gone forever and will never come back.

Time is, therefore, always in exceedingly short supply.

Time is totally irreplaceable.

Within limits we can substitute one resource for another, copper for aluminum, for instance.

We can substitute capital for human labor.

We can use more knowledge or more brawn.

But there is no substitute for time.

Everything requires time.

It is the one truly universal condition.

All work takes place in time and uses up time.

Yet most people take for granted this unique, irreplaceable, and necessary resource.

Nothing else,

perhaps,

distinguishes effective executives

as much as

their #tlcot tender loving care of time.

Those who want to live a fulfilling life

— The Effective Executive preface by Peter Drucker

Before proceeding further, please explore the previous Effective Executive link

“Concentration — that is, the courage to impose on time and events his own decision as to what really matters and comes first — is the executive’s only hope of becoming the master of time and events instead of their whipping boy” — The Effective Executive contents

“Follow effective action with quiet reflection.

From the quiet reflection will come even more effective action.” — Peter Drucker

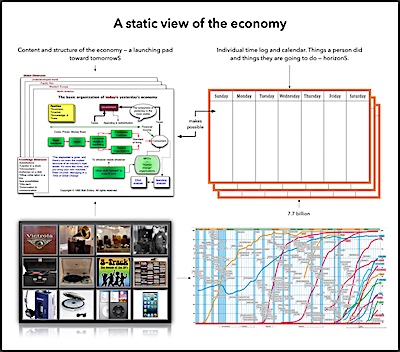

These ideas about WHAT we spend our time doing have major strategic implications for individuals, organizations, and society.

Organization efforts: problems or opportunities

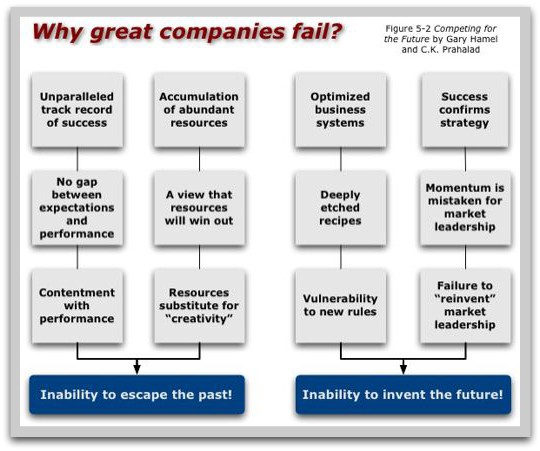

Making the future

One of Drucker's favorite sayings: Focus, Focus, Focus. (See How Drucker taught me to focus by Shao Ming Lo)

Different thoughts for different times

What exists is getting old (including dreams)

Dealing with risk and uncertainty #dwrau

To say that most executives spend most of their time tackling the problems of today is euphemism.

They spend most of their time on the problems of yesterday.

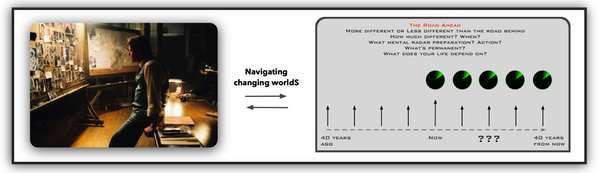

#ewtl = evidence wall + time line

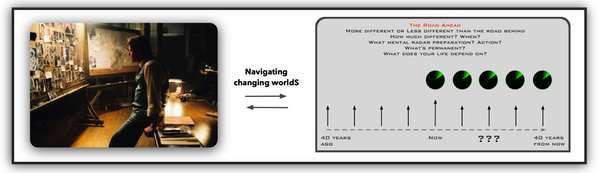

the road ahead?

What thinking is needed?

Realities:

Business realities, Market realities, and Knowledge realities

The Second Curve

“To raise the question (What is our business? — chapter 7,

Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices) always

reveals cleavages and differences

within the top-management group itself.”

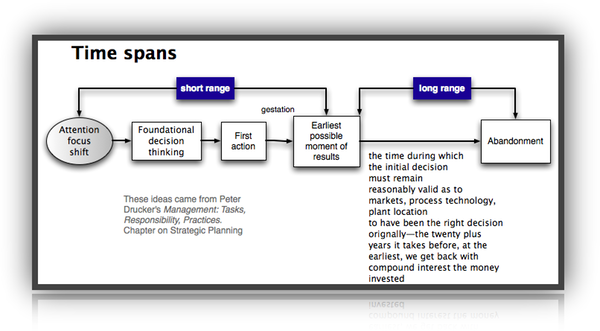

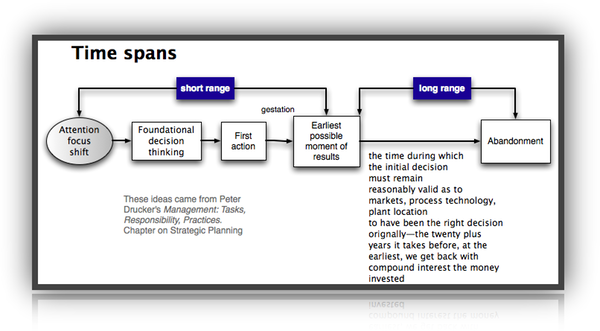

Decision making is a time machine

Executives spend more of their time trying to unmake the past than on anything else.

This, to a large extent, is inevitable.

What exists today is of necessity the product of yesterday.

The business itself—its present resources, its efforts and their allocation, its organization as well as its products, its markets and its customers—expresses necessarily decisions and actions taken in the past.

Its people, in the great majority, grew up in the business of yesterday.

Their attitudes, expectations, and values were formed at an earlier time; and they tend to apply the lessons of the past to the present.

Indeed, every business regards what happened in the past as normal, with a strong inclination to reject as abnormal whatever does not fit the pattern.

No matter how wise, forward-looking, or courageous the decisions and actions were when first made, they will have been overtaken by events by the time they become normal behavior and the routine of a business.

Long years of profound changeS

No matter how appropriate the attitudes were when formed, by the time their holders have moved into senior, policy-making positions, the world that made them no longer exists.

Events never happen as anticipated; the future is always different.

Just as generals tend to prepare for the last war, businessmen always tend to react in terms of the last boom or of the last depression.

What exists is therefore always aging.

Any human decision or action starts to get old the moment it has been made.

It is always futile to restore normality; “normality” is only the reality of yesterday.

The job is not to impose yesterday’s normal on a changed today;

but to change

the business,

its behavior,

its attitudes,

its expectations —

as well as its products,

its markets,

and its distributive channels —

to fit the new realities.

#ewtl = evidence wall + time line

The Five Deadly Sins

What executives should remember

Managing for Results

What happened to America before Columbus?

What happened to the empires in world history? GONE

Abandonment

A revolution in every generation

is not the answer

Dealing with risk and uncertainty

Entrepreneurial activities

There are no decisions more important than people decisions.

Drucker never forgot the lessons he had gleaned from Alfred Sloan.

Executives spend more time on managing people and making people decisions than on anything else—and they should insisted Drucker.

No decision is as long lasting in its consequences or as difficult to unmake.

He added that most executives make bad people decisions, with a batting average no better than 333: one third of new hires are good ones; one third are minimally effective, and one third are disasters.

Sloan’s people selection over the long run, contended Drucker, was flawless, because he made every key management decision personally.

And if it appears that Sloan micromanaged hiring decisions, he should be forgiven, simply because of how important his selections were to the success of GM.

After people decisions come the priority decisions: how to allocate resources.

The key is to put your best people where they can make the greatest impact.

Organizations that have their A players dealing with the mundane, such as turf battles, are mismanaged.

Last, don’t let investments in managerial ego get in the way of abandoning projects that have been postponed or sidetracked.

Inside Drucker’s Brain

AS WE ADVANCE deeper into the knowledge economy, the basic assumptions underlying much of what is taught and practiced in the name of management are hopelessly out of date. — Management's New Paradigm

High tech is living in the nineteenth century, the pre-management world. They believe that people pay for technology. They have a romance with technology. But people don't pay for technology: they pay for what they get out of technology. The Frontiers of Management

Analysis of the entire business and its basic economics always shows it to be in worse disrepair than anyone expected.

The products everyone boasts of turn out to be yesterday's breadwinners or investments in managerial ego.

Activities to which no one paid much attention turn out to be major cost centers and so expensive as to endanger the competitive position of the company.

What everyone in the business believes to be quality turns out to have little meaning to the customer.

Important and valuable knowledge either is not applied where it could produce results or produces results no one uses.

I know more than one executive who fervently wished at the end of the analysis that he could forget all he had learned and go back to the old days of the “rat race” when “sufficient unto the day was the crisis thereof.”

But precisely because there are so many different areas of importance, the day-by-day method of management is inadequate even in the smallest and simplest business.

Because deterioration is what happens normally—that is, unless somebody counteracts it—there is need for a systematic and purposeful program.

There is need to reduce the almost limitless possible tasks to a manageable number.

There is need to concentrate scarce resources on the greatest opportunities and results.

There is need to do the few right things and do them with excellence.

Managing for Results by Peter Drucker

The 90/10 Rule at Yum! Brands

But every analysis of actual allocation of resources and efforts in business that I have ever seen or made showed clearly that the bulk of time, work, attention, and money first goes to 'problems' rather than to opportunities, and, secondly, to areas where even extraordinarily successful performance will have minimal impact on results. (calendarize this?)

One of the hardest things for a manager to remember is that of the 1,000 different situations he or she will be asked to deal with on any given day, only the smallest handful have a shot at moving the enterprise forward in a truly significant way (calendarize this?)

The job of management, then, is to make sure that financial capital, technology, and top talent are deployed where most of the results are and where most of the costs aren't. The temptation often exists, however, to do exactly the opposite

Drucker said the problem of having people in positions where they do the least amount of good exists everywhere, but it is more rampant in hospitals, churches, and other nonprofits than in corporations.

To raise productivity in most any organization managers should regularly assess their key people, their strengths, and the results they achieve.

Then they should ask themselves:

Do we have the right people in the right jobs, where they can make the greatest contributions?

Are the jobs the right ones, meaning do we have people performing tasks that even if achieved do not add value to the organization?

What changes in people, jobs, and job functions can we make that will yield greater results?

Inside Drucker's Brain

“The stepladder is gone, and

there’s not even the implied structure

of an industry’s rope ladder.

It’s more like vines …

and you bring your own machete.

You don’t know what you’ll be doing next”

— Managing in a Time of Great Change

You can’t design your life around a temporary organization — Peter Drucker

NBC Universal's Jeff Zucker says he's being shown the door

Comcast's Steve Burke told him to 'move on' after the merger.

Jeff Zucker, a lifelong employee of NBC Universal, said Friday that he would step down as chief executive after being told there won't be a place for him once Philadelphia cable giant Comcast Corp. takes over the company at the end of the year.

Soros to return outsiders’ hedge fund money

(Reuters)—Billionaire investor George Soros, whose stock-picking career has spanned nearly four decades, said he will manage money only for himself and his family as new regulations threaten to crimp the hedge fund industry he made famous.

The octogenarian fund manager, known as much for earning $1 billion on a nervy currency bet as for giving away millions to support liberal causes, will return roughly $1 billion to outside investors most likely by the end of the year and turn Soros Fund Management into a family office. The sum represents only a small portion of the $25 billion he oversees.

Keith Anderson, who has been Soros' chief investment officer since 2008, will leave the firm.

Soros hires new chief investment officer

(Reuters)—Billionaire investor George Soros is continuing to overhaul the management team of his Soros Fund Management LLC, which is converting from a hedge fund to a family office.

The octogenarian fund manager, who is in the process of returning $1 billion to outside investors, announced in a September 19 letter that Scott Bessent is joining as the firm's new chief investment officer.

Bessent, a former Soros fund alum, most recently was a senior partner and director of research for Protege Partners. He will takeover for Keith Anderson, who stepped down as the fund's chief investment officer in July.

Starting Over is the New Norm

… In this age of corporate downsizing, mergers, outsourcing, layoffs, and mass dismissals, you may well have to come to terms with the idea that job security is rarely something to count on. … .

In short, the era of the paternal corporation that took care of people from cradle to crypt is over. Many studies show that a typical professional in this early part of the new millennium will need to change jobs six or seven times. That means that you have to be prepared to start over and over again.

On the face of it, that may seem daunting. Anyone who’s been fired knows how terrifying it is to be stripped suddenly of job security, not to mention a regular income. Foreclosures suddenly stare you in the face. Health insurance is gone. There’s the social embarrassment of being canned from one’s job. Marriages sometimes unravel as economic circumstances worsen. …

What preparation is required? See the article for his response. …

|

![]()

![]()