Realities

Business, Results, Resources, Efforts, Cost,

Market, Knowledge,

Making the Future,

Executive realities

and The New Realities

Text begins

About Peter Drucker ↓

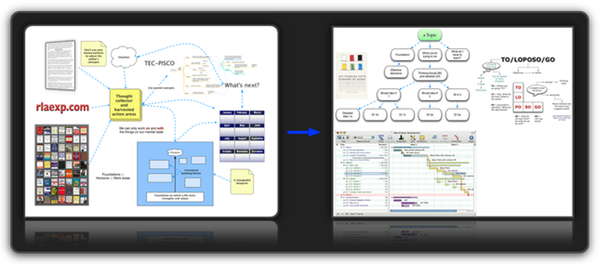

The brain can only see

what it

is prepared to see

«§§§»

To know something,

to really understand

something important,

one must look at it

from sixteen different angles.

People are perceptually slow,

and there is no shortcut

to understanding;

it takes a great deal of time. continue

«§§§»

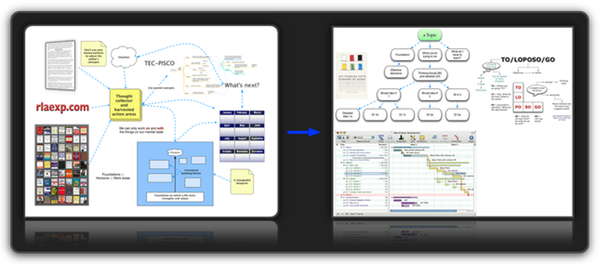

Your thinking, choices, decisions

are determined by

what you’ve

“SEEN”

“Once perception

is directed in a certain direction

it cannot help but see,

and once something is seen,

it cannot be unseen”

«§§§»

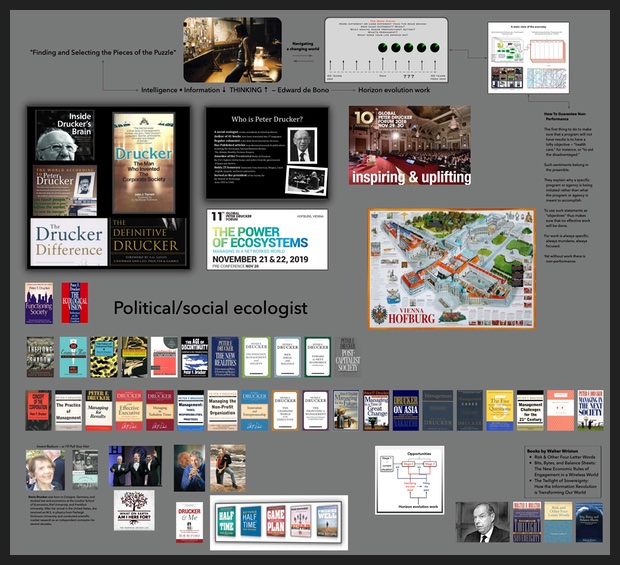

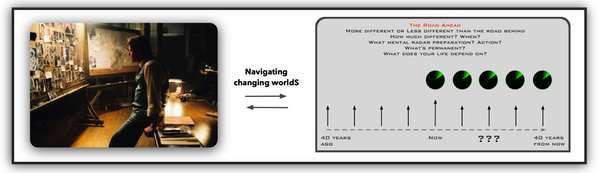

Being prepared for what comes next — and there’s no one to ask

Work has to make a life

finding and selecting the pieces of the puzzle

#Note the number of books about Drucker ↓

My life as a knowledge worker

Drucker: a political or social ecologist ↑ ↓

“I am not

a ‘theoretician’;

through my consulting practice

I am in daily touch with

the concrete opportunities and problems

of a fairly large number of institutions,

foremost among them businesses

but also hospitals, government agencies

and public-service institutions

such as museums and universities.

And I am working with such institutions

on several continents:

North America, including Canada and Mexico;

Latin America; Europe;

Japan and South East Asia.

Still, a consultant is at one remove

from the day-today practice —

that is both his strength

and his weakness.

And so my viewpoint

tends more to be that of an outsider.”

broad worldview ↑ ↓

Most mistakes in thinking ↑ are mistakes in PERCEPTION: …

Seeing only part of the situation;

Jumping to conclusions;

Misinterpretation caused by feelings …

#pdw larger ↑ ::: Books by Peter Drucker ::: Rick Warren + Drucker

Books by Bob Buford and Walter Wriston

Global Peter Drucker Forum ::: Charles Handy — Starting small fires

Post-capitalist executive ↑ T. George Harris

Your thinking, choices, decisions

are determined by

what you’ve “SEEN”

“Once perception is directed

in a certain direction

it cannot help but see,

and once something is seen,

it cannot be unseen”

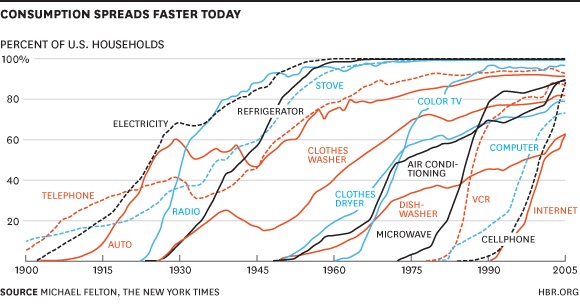

The speed of product and technology adoption

Work has to make a life

If you don’t design your own life

someone else will do it for you

↑ The Drucker Lectures:

Essential Lessons on

Management, Society, and Economy

↓

The Definitive Drucker:

Challenges For

Tomorrow's Executives

“More detailed map” ↑

About technology

A Year with Peter Drucker:

52 Weeks of Coaching

for Leadership Effectiveness

The Five Most Important Questions

You Will Ever Ask

About Your Nonprofit Organization

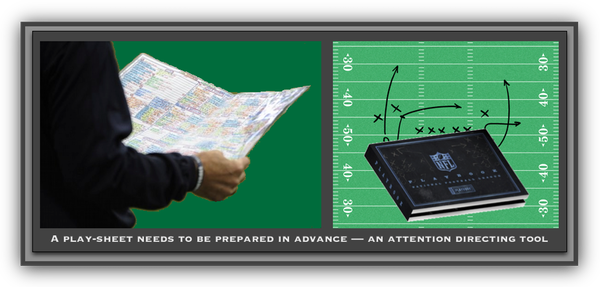

Danger of too much planning

Learning to Learn

↑ ecological awareness → operacy —

the skills of doing

The memo “THEY” don’t want you to SEE

“The world around is full of a huge number of things

to which one could pay attention.

But it would be impossible

to react to everything at once.

So one reacts only to

a selected part of it.

The choice of attention area

determines the action or thinking that follows.

The choice of this area of attention

is one of the most fundamental aspects

of thinking.” — Edward de Bono

About Managing for Results

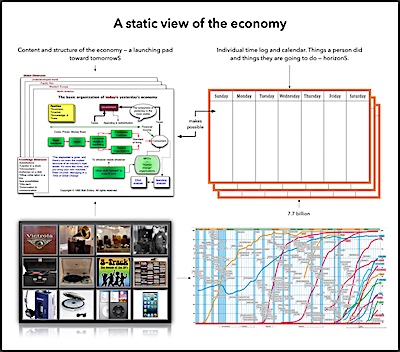

Today perceptiveness is more important than analysis

Business realities

Results and resources

Efforts and cost

What makes for leadership

Market realities

Knowledge realities

Making the future

The Future That Has Already Happened

The Power Of An Idea

Executives

Overview

Who Is An Executive?

Executive realities

What executives should remember

What makes an effective executive?

Overview of Eight Practices

What needs to be done

What is right for the organization — #org

Write An Action Plan

Act

Take responsibility for decisions

Take responsibility for communicating

Focus on opportunities

Make meetings productive

Think And Say “We”

Bonus Rule: Listen first, speak last

Effectiveness Can Be Learned

Why We Need Effective Executives

The absence of executives in yesterday’s organizations — #org

Today’s large knowledge organizations — #org

The New Realities

Competitive success

Managing for Results

The book is divided into three parts.

The The first—and longest—stresses analysis and understanding.

Chapter 1 deals with the “Business Realities”. the situation most likely to be found in any business at any given time.

The next three chapters (chapters 2, 3,4) develop the analysis of the result areas of the entire business and relate them to resources and efforts on the one hand and to opportunities and expectations on the other.

Chapter 5 projects a similar analysis on the cost stream and cost structure — both of the individual business and of the economic process of which it is part.

Chapters 6 and 7 deal with the understanding of a business from the “outside” where both the results and the resources are.

These chapters ask, “What do we get paid for?” and ‘What do we earn our keep with?”

In Chapter 8: All analyzes are pulled together into an understanding of the existing business, its fundamental economic characteristics, its performance capacity, its opportunities, and its needs.

Part II focuses on opportunities and leads to decisions.

It discusses the opportunities and needs in each of the major economic dimensions of a business:

making the present business effective (Chapter 9);

finding and realizing business potential (Chapter 10);

making the future of the business today (Chapter 11).

The last-and shortest-part presents the conversion of insights and decisions into purposeful performance.

This requires that key decisions be made regarding the idea and objectives of the business, the excellences it needs, and the priorities on which it will concentrate (Chapter 12).

It requires a number of strategic choices: what opportunities to pursue and what risks to assume; how to specialize and how to diversify; whether to build or to acquire; and what organization is most appropriate to the economics of the business and to its opportunities (Chapter 13).

Chapter 14 finally embeds the entrepreneurial decisions for performance in the managerial structure of the organization-in work, in business practices, and in the spirit of the organization and its decisions on people.

The Conclusion projects the book and its thesis on the individual executive and his commitment and especially on the commitment of top management.

Any first attempt at converting folklore into knowledge, and a guessing game into a discipline, is liable to be misread as a downgrading of individual ability and its replacement by a rule book.

Any, such attempt would be nonsense, of course.

No book will ever make a wise man out of a donkey or a genius out of an incompetent.

The foundation in a discipline, however, gives to today’s competent physician a capacity to perform well beyond that of the ablest doctor of a century ago, and enables the outstanding physician of today to do what the medical genius of yesterday could hardly have dreamt of.

No discipline can lengthen a man’s arm.

But it can lengthen his reach by hoisting him on the shoulders of his predecessors.

Knowledge organized in a discipline does a good deal for the merely competent; it endows him with some effectiveness.

It does infinitely more for the truly able; it endows him with excellence.

Executives have the economic job anyhow.

Most work at it hard — too hard in many cases.

This book poses no additional work.

On the contrary, it aims to help them do their job with less effort and in less time, and yet with greater impact.

It does not tell them how to do things right.

It attempts to help them find the right things to do.

Business Realities

That executives give neither sufficient time nor sufficient thought to the future is a universal complaint.

Every executive voices it when he talks about his own working day and when he talks or writes to his associates.

It is a recurrent theme in the articles and in the books on management.

It is a valid complaint.

Executives should spend more time and thought on the future of their business.

They also should spend more time and thought on a good many other things, their social and community responsibilities for instance.

Both they and their businesses pay a stiff penalty for these neglects.

And yet, to complain that executives spend so little time on the work of tomorrow is futile.

The neglect of the future is only a symptom; the executive slights tomorrow because he cannot get ahead of today.

That too is a symptom.

The real disease is the absence of any foundation of knowledge and system for tackling the economic tasks in business.

Today’s job takes all the executive’s time, as a rule; yet it is seldom done well.

Few managers are greatly impressed with their own performance in the immediate tasks.

They feel themselves caught in a “rat race,” and managed by whatever the mail-boy dumps into their “in” tray.

They know that crash programs which attempt to “solve” this or that particular “urgent” problem rarely achieve right and lasting results.

And yet, they rush from one crash program to the next.

Worse still, they known that the same

Problems recur again and again, no matter how many times they are “solved.”

Before an executive can think of tackling the future, he must be able therefore to dispose of the challenges of today in less time and with greater impact and permanence.

For this he needs a systematic approach to today’s job.

There are three different dimensions to the economic task:

(1) The present business must be made effective;

(2) its potential must be identified and realized;

(3) it must be made into a different business for a different future.

Each task requires a distinct approach.

Each asks different questions.

Each comes out with different conclusions.

Yet they are inseparable.

All three have to be done at the same time: today.

All three have to be carried out with the same organization, the same resources of men, knowledge, and money, and in the same entrepreneurial process.

The future is not going to be made tomorrow;

it is being made today,

and largely

by the decisions and actions taken

with respect to the tasks of today.

Conversely, what is being done to bring about the future directly affects the present.

The tasks overlap.

They require one unified strategy.

Otherwise, they cannot really get done at all.

To tackle any one of these jobs, let alone all three together, requires an understanding of the true realities of the business as an economic system, of its capacity for economic performance, and of the relationship between available resources and possible results.

Otherwise, there is no alternative to the “rat race.”

This understanding never comes readymade; it has to be developed separately for each business.

Yet the assumptions and expectations that underlie it are largely common.

Businesses are different, but business is much the same, regardless of size and structure, of products, technology and markets, of culture and managerial competence.

There is a common business reality.

There are actually two sets of generalizations that apply to most businesses most of the time: one with respect to the results and resources of a business, one with respect to its efforts.

Together they lead to a number of conclusions regarding the nature and direction of the entrepreneurial job.

Most of these assumptions will sound plausible, perhaps even familiar, to most businessmen, but few businessmen ever pull them together into a coherent whole.

Few draw action conclusions from them, no matter how much each individual statement agrees with their experience and knowledge.

As a result, few executives base their actions on these, their own assumptions and expectations.

Results and resources

1. Neither results nor resources exist inside the business.

Both exist outside.

There are no profit centers within the business; there are only cost centers.

The only thing one can say with certainty about any business activity, whether engineering or selling, manufacturing or accounting, is that it consumes efforts and thereby incurs costs.

Whether it contributes to results remains to be seen.

Results depend not on anybody within the business nor on anything within the control of the business.

They depend on somebody outside—the customer in a market economy, the political authorities in a controlled economy.

It is always somebody outside who decides whether the efforts of a business become economic results or whether they become so much waste and scrap.

The same is true of the one and only distinct resource of any business: knowledge.

Other resources, money or physical equipment, for instance, do not confer any distinction.

What does make a business distinct and what is its peculiar resource is its ability to use knowledge of all kinds—from scientific and technical knowledge to social, economic, and managerial knowledge.

It is only in respect to knowledge that a business can be distinct, can therefore produce something that has a value in the market place.

Yet knowledge is not a business resource.

It is a universal social resource.

It cannot be kept a secret for any length of time.

“What one man has done, another man can always do again” is old and profound wisdom.

The one decisive resource of business, therefore, is as much outside of the business as are business results.

Indeed, business can be defined as a process that converts an outside resource, namely knowledge, into outside results, namely economic values.

2. Results are obtained by exploiting opportunities, not by solving problems.

All one can hope to get by solving a problem is to restore normality.

All one can hope, at best, is to eliminate a restriction on the capacity of the business to obtain results.

The results themselves must come from the exploitation of opportunities.

3. Resources, to produce results, must be allocated to opportunities rather than to problems.

Needless to say, one cannot shrug off all problems, but they can and should be minimized.

Economists talk a great deal about the maximization of profit in business.

This, as countless critics have pointed out, is so vague a concept as to be meaningless.

But “maximization of opportunities” is a meaningful, indeed a precise, definition of the entrepreneurial job.

It implies that effectiveness rather than efficiency is essential in business.

The pertinent question is not how to do things right but how to find the right things to do, and to concentrate resources and efforts on them.

4. Economic results are earned only by leadership, not by mere competence.

Profits are the rewards for making a unique, or at least a distinct, contribution in a meaningful area; and what is meaningful is decided by market and customer.

Profit can only be earned by providing something the market accepts as value and is willing to pay for as such.

And value always implies the differentiation of leadership.

The genuine monopoly, which is as mythical a beast as the unicorn (save for politically enforced, that is, governmental monopolies), is the one exception.

This does not mean that a business has to be the giant of its industry nor that it has to be first in every single product line, market, or technology in which it is engaged.

To be big is not identical with leadership.

In many industries the largest company is by no means the most profitable one, since it has to carry product lines, supply markets, or apply technologies where it cannot do a distinct, let alone a unique job.

The second spot, or even the third spot is often preferable, for it may make possible that concentration on one segment of the market, on one class of customer, on one application of the technology, in which genuine leadership often lies.

In fact, the belief of so many companies that they could—or should—have leadership in everything within their market or industry is a major obstacle to achieving it.

But a company which wants economic results has to have leadership in something of real value to a customer or market.

It may be in one narrow but important aspect of the product line, it may be in its service, it may be in its distribution, or it may be in its ability to convert ideas into salable products on the market speedily and at low cost.

Unless it has such leadership position, a business, a product, a service, becomes marginal.

It may seem to be a leader, may supply a large share of the market, may have the full weight of momentum, history, and tradition behind it But the marginal is incapable of survival in the long run, let alone of producing profits.

It lives on borrowed time.

It exists on sufferance and through the inertia of others.

Sooner or later, whenever boom conditions abate, it will be squeezed out.

The leadership requirement has serious implications for business strategy.

It makes most questionable, for instance, the common practice of trying to catch up with a competitor who has brought out a new or improved product.

All one can hope to achieve thereby is to become a little less marginal.

It also makes questionable “defensive research” which throws scarce and expensive resources of knowledge into the usually futile task of slowing down the decline of a product that is already obsolete.

5. Any leadership position is transitory and likely to be short lived.

No business is ever secure in its leadership position.

The market in which the results exist, and the knowledge which is the resource, are both generally accessible.

No leadership position is more than a temporary advantage.*1

1 * This is nothing but a restatement of Schumpeter’s famous theorem that profits result only from the innovator’s advantage and therefore disappear as soon as the innovation has become routine.

In business (as in a physical system) energy always tends toward diffusion.

Business tends to drift from leadership to mediocrity.

And the mediocre is three-quarters down the road to being marginal.

Results always drift from earning a profit toward earning, at best, a fee which is all competence is worth.

It is, then, the executive’s job to reverse the normal drift.

It is his job to focus the business on opportunity and away from problems, to re-create leadership and counteract the trend toward mediocrity, to replace inertia and its momentum by new energy and new direction.

The second set of assumptions deals with the efforts within the business and their cost.

6. What exists is getting old.

To say that most executives spend most of their time tackling the problems of today is euphemism.

They spend most of their time on the problems of yesterday.

Executives spend more of their time trying to unmake the past than on anything else.

This, to a large extent, is inevitable.

What exists today is of necessity the product of yesterday.

The business itself—its present resources, its efforts and their allocation, its organization as well as its products, its markets and its customers—expresses necessarily decisions and actions taken in the past.

Its people, in the great majority, grew up in the business of yesterday.

Their attitudes, expectations, and values were formed at an earlier time; and they tend to apply the lessons of the past to the present.

Indeed, every business regards what happened in the past as normal, with a strong inclination to reject as abnormal whatever does not fit the pattern.

No matter how wise, forward-looking, or courageous the decisions and actions were when first made, they will have been overtaken by events by the time they become normal behavior and the routine of a business.

No matter how appropriate the attitudes were when formed, by the time their holders have moved into senior, policy-making positions, the world that made them no longer exists.

Events never happen as anticipated; the future is always different.

Just as generals tend to prepare for the last war, businessmen always tend to react in terms of the last boom or of the last depression.

What exists is therefore always aging.

Any human decision or action starts to get old the moment it has been made.

It is always futile to restore normality; “normality” is only the reality of yesterday.

The job is not to impose yesterday’s normal on a changed today; but to change the business, its behavior, its attitudes, its expectations—as well as its products, its markets, and its distributive channels—to fit the new realities.

7. What exists is likely to be misallocated.

Business enterprise is not a phenomenon of nature but one of society.

In a social situation, however, events are not distributed according to the “normal distribution” of a natural universe (that is, they are not distributed according to the bell-shaped Gaussian curve).

In a social situation a very small number of events at one extreme—the first 10 per cent to 20 per cent at most—account for 90 per cent of all results; whereas the great majority of events accounts for 10 per cent or so of the results.

This is true in the market place: a handful of large customers out of many thousands produce the bulk of orders; a handful of products out of hundreds of items in the line produce the bulk of the volume; and so on.

It is true of sales efforts: a few salesmen out of several hundred a!ways produce two-thirds of all new business.

It is true in the plant: a handful of production runs account for most of the tonnage.

It is true of research: the same few men in the laboratory are apt to produce nearly all the important innovations.

It also holds true for practically all personnel problems: the bulk of the grievances always comes from a few places or from one group of employees (for example, from the older unmarried women or from the clean-up men on the night shift), as does the great, bulk of absenteeism, of turnover, of suggestions under a suggestion system, of accidents.

As studies at the New York Telephone Company have shown, this is true even in respect to sickness.

The implications of this simple statement about normal distribution are broad.

It means, first: while 90 per cent of the results are being produced by the first 10 per cent of events, 90 per cent of the costs are incurred by the remaining and resultless 90 per cent of events.

In other words, results and costs stand in inverse relationship to each other.

Economic results are, by and large, directly proportionate to revenue, while costs are directly proportionate to the number of transactions.

(The only exceptions are the purchased materials and parts that go directly into the final product.)

A second implication is that resources and efforts will normally allocate themselves to the 90 per cent of events that produce practically no results.

They will allocate themselves to the number of events rather than to the results.

In fact, the most expensive and potentially most productive resources (i. e., highly trained people) will misallocate themselves the worst.

For the pressure exerted by the bulk of transactions is fortified by the individual’s pride in doing the difficult—whether productive or not.

This has been proved by every study.

Let me give some examples:

A large engineering company prided itself on the high quality and reputation of its technical service group, which contained several hundred expensive men.

The men were indeed first-rate.

But analysis of their allocation showed clearly that while they worked hard, they contributed little.

Most of them worked on the “interesting” problems—especially those of the very small customers—problems which, even if solved, produced little business.

The automobile industry was the company’s major customer and accounted for almost one-third of all purchases.

But few technical service people had within memory set foot in the engineering department or the plant of an automobile company.

“General Motors and Ford don’t need me; they have their own people” was their reaction.

Similarly, in many companies, salesmen are misallocated.

The largest group of salesmen (and the most effective ones) are usually put on the products that are hard to sell, either because they are yesterday’s products or because they are also-rans which managerial vanity desperately is trying to make into winners.

Tomorrow’s important products rarely get the sales effort required.

And the product that has sensational success in the market, and which therefore ought to be pushed all out, tends to be slighted.

“It is doing all right without extra effort, after all” is the common conclusion.

Research departments, design staffs, market development efforts, even advertising efforts have been shown to be allocated the same way in many companies—by transactions rather than by results, by what is difficult rather than by what is productive, by yesterday’s problems rather than by today’s and tomorrow’s opportunities.

A third and important implication is that revenue money and cost money are rarely the same money stream.

Most businessmen see in their mind’s eye—and most accounting presentations assume—that the revenue stream feeds back into the cost stream, which then, in turn, feeds back into the revenue stream.

But the loop is not a closed one.

Revenue obviously produces the wherewithal for the costs.

But unless management constantly works at directing efforts into revenue-producing activities, the costs will tend to allocate themselves by drifting into nothing-producing activities, into sheer busy-ness.

In respect then to efforts and costs as well as to resources and results the business tends to drift toward diffusion of energy.

There is thus need for constant reappraisal and redirection; and the need is greatest where it is least expected: in making the present business effective.

It is the present in which a business first has to perform with effectiveness.

It is the present where both the keenest analysis and the greatest energy are required.

Yet it is dangerously tempting to keep on patching yesterday’s garment rather than work on designing tomorrow’s pattern.

A piecemeal approach will not suffice.

To have a real understanding of the business, the executive must be able to see it in its entirety.

He must be able to see its resources and efforts as a whole and to see their allocation to products and services, to markets, customers, end-uses, to distributive channels.

He must be able to see which efforts go onto problems and which onto opportunities.

He must be able to weigh alternatives of direction and allocation.

Partial analysis is likely to misinform and misdirect.

Only the over-all view of the entire business as an economic system can give real knowledge.

8. Concentration is the key to economic results.

Economic results require that managers concentrate their efforts on the smallest number of products, product lines, services, customers, markets, distributive channels, end-uses, and so on, that will produce the largest amount of revenue.

Managers must minimize the amount of attention devoted to products which produce primarily costs because, for instance, their volume is too small or too splintered.

Economic results require that staff efforts be concentrated on the few activities that are capable of producing significant business results.

Effective cost control requires a similar concentration of work and efforts on those few areas where improvement in cost performance will have significant impact on business performance and results—that is, on those areas where a relatively minor increase in efficiency will produce a major increase in economic effectiveness.

Finally, human resources must be concentrated on a few major opportunities.

This is particularly true for the high-grade human resources through which knowledge becomes effective in work.

And, above all it is true for the scarcest, most expensive, but also potentially most effective of all human resources in a business: managerial talent.

No other principle of effectiveness is violated as constantly today as the basic principle of concentration.

This, of course, is true not only of businesses.

Governments try to do a little of everything.

Today’s big university (especially in the United States) tries to be all things to all men, combining teaching and research, community services, consulting activities, and so on.

But business—especially large business—is no less diffuse.

Only a few years ago it was fashionable to attack American industry for “planned obsolescence.”

And it has long been a favorite criticism of industry, especially American industry, that it imposes “deadening standardization.”

Unfortunately industry is being attacked for doing what it should be doing and fails to do.

Large United States corporations pride themselves on being willing and able to supply any specialty, to satisfy any demand for variety, even to stimulate such demands.

Any number of businesses boast that they never of their own free will abandon a product.

As a result, most large companies end up with thousands of items in their product line—and all too frequently fewer than twenty really sell.

However, these twenty or fewer items have to contribute revenues to carry the costs of the 9,999 non-sellers.

Indeed, the basic problem of United States competitive strength in the world today may be product clutter.

If properly costed, the main lines in most of our industries prove to be fully competitive, despite our high wage rate and our high tax burden.

But we fritter away our competitive advantage in the volume products by subsidizing an enormous array of specialties, of which only a few recover their true cost.

In electronics, for instance, the competition of the Japanese portable transistor radio rests on little more than the Japanese concentration on a few models in this one line—as against the uncontrolled plethora of barely differentiated models in the United States manufacturers’ lines.

We are similarly profligate in this country with respect to staff activities.

Our motto seems to be: “Let’s do a little bit of everything”—personnel research, advanced engineering, customer analysis, international economics, operations research, public relations, and so on.

As a result, we build enormous staffs, and yet do not concentrate enough effort in any one area.

Similarly, in our attempts to control costs, we scatter our efforts rather than concentrate them where the costs are.

Typically the cost-reduction program aims at cutting a little bit—say, 5 or 10 per cent-off everything.

This across-the-board cut is at best ineffectual; at worst, it is apt to cripple the important, result-producing efforts which usually get less money than they need to begin with.

But efforts that are sheer waste are barely touched by the typical cost-reduction program; for typically they start out with a generous budget.

These are the business realities, the assumptions that are likely to be found valid by most businesses at most times, the concepts with which the approach to the entrepreneurial task has to begin.

They have only been sketched here in outline; each will be discussed in detail in the course of the book.

That these are only assumptions should be stressed.

They ‘must be tested by actual analysis; and one or the other assumption may well be found not to apply to any one particular business at any one particular time.

Yet they have sufficient probability to provide the foundation for the analysis the executive needs to understand his business.

They are the starting points for the analysis needed for all three of the entrepreneurial tasks: making effective the present business; finding business potential; and making the future of the business.

The small and apparently simple business needs this understanding just as much as does the big and highly complex company.

Understanding is needed as much for the immediate task of effectiveness today as it is for work on the future, many years hence.

It is a necessary tool for any executive who takes seriously his entrepreneurial responsibility.

And it is a tool which can neither be fashioned for him nor wielded for him.

He must take part in making it and using it.

The ability to design and develop this tool and the competence to use it should be standard equipment for the business executive.

II What Makes For Leadership?

Experienced businessmen know that the seemingly simple statements regarding position and prospects of each product in Table II represent the final summation of a great deal of hard work and prolonged discussion.

In these areas even calm men will get angry, and reasonable men will refuse to listen to facts with a curt: “I don’t believe it.”

Here, in other words, is need for thorough, painstaking work.

But the work itself—its tools and techniques—from value-analysis of the product to market research—is well known, has indeed been routine for years even in fairly small businesses.

The results, in other words, may be controversial and hard to accept; but the work itself is familiar.

Of course, presentation in a large and complex company will be far more detailed than in smaller businesses.

A good deal will be quantified, and so on.

But it is not my intention here to show how complicated one can become—nor does anyone need this lesson.

I am intent only on getting across a concept—and the concept is simple.

Leadership is not a quantitative term.

The business with the largest share of a market may have leadership in one segment only.

The monopolist, the single supplier of a product or of a market, never has leadership and cannot have it.

To have leadership a product must be best fitted for one—or more—of the genuine wants of market and customer.

It must be a genuine want.

The customer must be willing to pay for it.

No matter how desirable a certain quality in a product might appear to the manufacturer, it only gives leadership if the customer accepts the claim.

His acceptance is his willingness to honor the claim in tangible form by preferring the product to its competitors—and by being willing to pay.

The monopolist cannot have leadership because the customer cannot choose.

Customers of a monopoly always want a second supplier and flock to him when he appears.

They may have been fully satisfied with the monopolist’s goods or services.

But it is an exceptional business or product that, after having had a monopoly, retains customer preference.*1

1 * Incidentally, the sole-source supplier has lower sales, as a rule, than he would have were there competitors in the field.

Sales of a product line of any consequence do not begin to expand, let alone to reach their potential, as long as only one company supplies them.

The history of the aluminum industry in the United States is an example.

Though the Aluminum Company of America was the very model of the “enlightened monopolist” who constantly lowers price and seeks new uses for his product, the explosive expansion of aluminum consumption in this country started after the United States government, during World War II, had put two other companies into the aluminum business.

Part of the reason for this failure of monopoly to benefit even the monopolist is certainly that one company, no matter how big, is rarely big enough to develop a new market of any size by itself; it takes at least two.

There is rarely “one right way” in a new market.

Yet alternatives are unlikely to be thought of or aggressively explored unless there is the challenge of competition.

Another reason is probably that even the “enlightened monopolist” tends to neglect markets and customers that cannot go elsewhere.

But a main reason is certainly that manufacturer, wholesaler, retailer, or consumer dislikes to be dependent on a single source of supply and therefore keeps down his purchases from a supplier in control of the market.

The monopolist is therefore always in danger of becoming marginal the moment a second supplier appears.

Most businessmen know this to be true—but emotionally they find it hard to accept.

Yet, in analyzing a business, one had best consider an unchallenged product as an endangered product.

The common test of leadership by “share of the market” is also deceptive.

Examples abound of companies that have the largest share of the market but are far behind in their profitability compared to competitors of much smaller apparent stature.

This means that they do not get paid for leadership but, in effect, have to pay for it.

For while the very large company has to be active in every area, no company, as a rule, can have real distinction in everything.

In all of American industry there is only one example of a company that combines first rank in every area with first rank in profitability in every area: General Motors in the U.S. automobile market.

DuPont de Nemours, while the largest and most profitable of American chemical companies, works only in a few segments of industrial chemistry, especially in chemicals and fibers for the textile market.

There are, to be sure, few situations comparable to that of U.S. Steel, the price and volume leader in most steel markets for many years but until a few years ago the least profitable large American steel company.

Here largest share of the market seems to have been held by a producer who was marginal in the major product areas.

But in most industries the largest company has leadership in only a few areas, while its very size and prominence force it to be active in a great many others.

Only an occasional very small specialty business can be the leader with all of its products or services, in all its markets and end-uses, with all its customers, and in all its distributive channels.

But no company, no matter how large or how small, can afford to be marginal in all of them.

Above all it cannot afford to be anything but a leader in the areas which are the mainstay of its business, produce the bulk of the sales, generate the bulk of the costs, and absorb the most important and most valuable resources.

A marginal product generates inadequate returns.

It is always in danger of being squeezed out altogether.

The larger the market the more dangerous is it to be marginal, the less room is there for any but products with genuine leadership position.

Contrary to what economists have been preaching for two hundred years, the alternative to monopoly in a developed, large market is not free competition—that is, an unlimited number of participants in an industry; but oligopoly—that is, competition between a fairly small number of manufacturers or suppliers.

As the market gets bigger, it may take so much money to enter the industry that the attempt can be made only once in a great while—simply because one must either sell nationally or not sell at all (as in the American automobile industry).

The bigger the market, the more will distributive channels concentrate on just enough well-known brands to give the customer meaningful choice, but not so many as to confuse him or as to require excessive inventories.

For this reason, for instance, concentration of the American kitchen-appliance industry (refrigerators, ranges, dishwashers, automatic laundries, etc.) on no more than half a dozen or so major brands will occur sooner or later whatever the antitrust laws may say to the contrary.

Five to six major brands are all that a large appliance dealer—whether a discount house, a department store, or a shopping center—needs in order to have a full line which gives the customer all the selection he wants.

More brands, as a matter of fact, may only confuse the customer and may make him not want to buy.

More brands do not increase sales, but they do increase inventory.

They tie up money, floor space, and warehouse space.

They make repair service difficult: the repairman has to be trained on more appliances and has to carry more spare parts.

They either require additional promotion money or splinter the promotion impact, and so on.

The first reaction of the appliance dealer in this situation is to put pressure for “extras” on the manufacturers of the slower-selling lines.

During the last decade dealers have asked for and received lower prices, larger discounts, special financing, extra promotion allowances, and guarantees of repurchase of used appliances at a stipulated price well above the market.

Each demand meant a decrease in the manufacturer’s profitability.

If and when a really sharp setback in the appliance market occurs, the marginal brands will then be squeezed out altogether—simply because dealers have to curtail their inventories and therefore concentrate on the few fast-selling brands and drop the others.

The main reason why concentration increases, the larger and more highly developed the market, is that the large market makes for meaningful product differentiation.

The larger the market the less room it has for products that are “just as good,” the less room there is for marginal products and marginal producers.

This may be of particular importance today for Europe and for Japan where the mass-market is developing rapidly.

A business or product that was a leader in the restricted German or French market of yesterday may rapidly become marginal in the mass-market of the unified European continent.

This is certainly a major factor behind the rapid mergers and partnership associations between medium-sized companies—especially family-owned ones—across Common Market national boundaries.

And unless they try to establish monopolies that restrict the market, such combinations of medium-sized businesses into one large group or association are healthy—are indeed needed fully to exploit the economic potential of the Common Market or of Japan’s new mass-consumer economy.

The expansion of a market also creates opportunities for a host of products and services with special characteristics to attain leadership position in a distinct market-segment or end-use which, while significantly smaller than the national or mass market, is still larger than what passed for the big market only a while back.

Take for example the market for specially formulated polymer petrochemicals.

The manufacturers of the large, volume polymer products—e. g., the main plastics—are the principal customers; and the opportunities, sales, and profits for the accomplished polymer chemist are high.

The Cummins Engine Company of Columbus, Indiana—a medium-sized business—has enjoyed highly profitable leadership as a maker of engines for heavy trucks.

If the very large engineering companies (General Motors above all) did not offer a broad assortment of diesel engines for all uses—in buses, in ships, in locomotives—Cummins could hardly have confined itself to the specialization on one narrow line that underlies its success.

Either an engine design is used widely or it becomes so difficult to install and service that it is not used at all.

Some small manufacturers, each specializing in one or two special applications of low-horsepower electrical motors, have been doing proportionately better than General Electric or Westinghouse, whose dominant market share forces them to supply all kinds of motors to all customers and for all end-uses, and who therefore, of necessity, must be marginal or lose money on some lines.

A leadership position may be based on price or on reliability.

Easy maintenance may be crucial in one product for one purpose; a promise that no maintenance is needed may be leadership for a similar product in some other use (e. g., for a telephone cable laid on the ocean floor or for a microwave relay station for telephone and television signals built on a mountain top in Idaho, sixty miles and two blizzards from the nearest town).

Appearance, style, design—customer recognition and acceptance—lowest cost of a finished article into which a product is being converted—small or large size—service and speedy delivery—technical counsel—these and many others can be foundations for a leadership position.

But what the manufacturer considers “quality” is not one of them; it is only too often irrelevant, if not the manufacturer’s alibi for turning out a marginal product that costs more but does not contribute anything different or better.

There is no leadership if the market is not willing to recognize the claim.

And that always means willingness to buy and to pay.

Leadership position for a product or a business is an economic term rather than a moral or an esthetic one.

Low price may be no criterion at all.

(Indeed manufacturers’ complaints that “the trade” buys only by price and pays no attention to quality are often unfounded; the trade has definite value preferences and is willing to pay for them—the manufacturer just does not satisfy them.)

But customer willingness to pay and customer purchases in preference to competitors’ products are valid criteria of economic accomplishment in a competitive market economy.

If they cannot be clearly demonstrated, a product must be suspected of being—or becoming—marginal.

In analyzing products for their leadership position, the same questions should therefore always be asked:

“Is the product being bought in preference to other products on the market, or at least as eagerly?”

“Do we have to give anything to get the customer to buy?”

(e. g., the extraordinary amount of service which, as Table Ill (next page) shows, products F and 0 require).

“Do we get paid for what we deliver to him, as indicated by an at-least-average profit contribution?”

“Are we getting paid for what we think is the product distinction?”

“Or do we have a product with leadership position and with distinction without ourselves discerning it?”

(as might well be the case with products C and D in the tables).

If the main products of a company show no signs of having such distinction and of occupying leadership position—as may be the case with Universal Products—it had better do something fast, especially if sales and profits seem to be doing well.

Both sales and profits may suddenly collapse—yet no one is prepared, no one is forewarned, no one is working at restoring the leadership position of the products or developing new ones to replace what has become marginal.

Turning now to the prospects, Table II (page 39) summarized a lot of hard work—and even more internal disagreement.

Judgments on prospects—on what can reasonably be expected of a product within the next few years—are of course fully as controversial as leadership position.

One look at the table and every experienced executive knows that the prospect appraisal for product A will be bitterly disputed, especially by the engineering department, and that the dismal appraisal for product B is probably still too optimistic.

He knows that the comptroller will challenge the high appraisal of the prospect for product D; whereas sales may want to push the estimate even higher.

The expectation of continued sales for product I, even though on a very low level, is probably wishful thinking.

The old-timers who made their careers designing, making, and selling it still hope it will come back.

But what the analysis tries to do—and why it should be made—hardly needs explanation.

The amazing thing is that it is done so rarely.

Individual products are frequently studied and their prospects assayed.

Major markets too—e. g., the market for construction materials—may be studied, especially by the larger companies.

But a searching look at the prospects of all the products at the same time, let alone of all result areas of a business, is still uncommon—even in companies that profess to believe in long-range planning.

Yet it is both an easy thing to do—though not so easy to do well—and a most revealing, question—raising approach to the business and its capacity to perform and to produce results.

Market Realities

All this is hardly news for businessmen any more.

For a decade now the “marketing view” has been widely publicized.

It has even acquired a fancy name: The Total Marketing Approach.

Not everything that goes by that name deserves it.

“Marketing” has become a fashionable term.

But a gravedigger remains a gravedigger even when called a “mortician”—only the cost of the burial goes up.

Many a sales manager has been renamed “marketing vice president”—and all that happened was that costs and salaries went up.

A good deal of what is called “marketing” today is at best organized, systematic selling in which the major jobs—from sales forecasting to warehousing and advertising—are brought together and coordinated.

This is all to the good.

But its starting point is still our products, our customers, our technology.

The starting point is still the inside.

Yet there have been enough serious efforts for us to know what we mean by the marketing analysis of a business, and how one goes about it.

Here, first, are the marketing realities that are most likely to be encountered:

1. What the people in the business think they know about customer and market is more likely to be wrong than right.

There is only one person who really knows: the customer.

Only by asking the customer, by watching him, by trying to understand his behavior can one find out who he is, what he does, how he buys, how he uses what he buys, what he expects, what he values, and so on.

2. The customer rarely buys what the business thinks it sells him.

One reason for this is, of course, that nobody pays for a “product.”

What is paid for is satisfactions.

But nobody can make or supply satisfactions as such—at best, only the means to attaining them can be sold and delivered.

Every few years this axiom is rediscovered by a newcomer to the advertising business who becomes an overnight sensation on Madison Avenue.

For a few months he brushes aside what the company’s executives tell him about the product and its virtues, and instead turns to the customer and, in effect, asks him: “And what do you look for?

Maybe this product has it.”

The formula has never failed—not since it was used, many years ago, to promote an automobile with the slogan, “Ask the Man Who Owns One”; that is, with the promise of customer satisfaction.

But it is so difficult for the people who make a product to accept that what they make and sell is the vehicle for customer satisfaction, rather than customer satisfaction itself, that the lesson is always immediately forgotten, until the next Madison Avenue sensation rediscovers it.

3. A corollary is that the goods or services which the manufacturer sees as direct competitors rarely adequately define what and whom he is really competing with.

They cover both too much and too little.

Luxury cars—the Rolls Royce and the Cadillac, for instance—are obviously not in real competition with low-priced automobiles.

However excellent Rolls Royce and Cadillac may be as transportation, they are mainly being bought for the prestige satisfaction they give.

Because the customer buys satisfaction, all goods and services compete intensively with goods and services that look quite different, seem to serve entirely different functions, are made, distributed, sold differently—but are alternative means for the customer to obtain the same satisfaction.

That the Cadillac competes for the customer’s money with mink coats, jewelry, the skiing vacation in the luxury resort, and other prestige satisfactions, is an example—and one of the few both the general public and the businessman understand.

But the manufacturer of bowling equipment also does not, primarily, compete with the other manufacturers of bowling equipment.

He makes physical equipment.

But the customer buys an activity.

He buys something to do rather than something to have.

The competition is therefore all the other activities that compete for the rapidly growing “discretionary time” of an affluent, urban population—boating and lawn care, for instance, but also the continuing postgraduate education of already highly schooled adults (which has been the true growth industry in the United States these last twenty years).

That the bowling equipment makers were first in realizing the potential and growth of the discretionary-time market, first to promote a new family activity, explains their tremendous success in the fifties.

That they, apparently, defined competition as other bowling equipment makers rather than as all suppliers of activity—satisfactions is in large part responsible for the abrupt decline of their fortunes in the sixties.

They apparently had not even realized that other activities were invading the discretionary—time market; and they had not given thought to developing a successor-activity to a product that, in the activities market, was clearly becoming yesterday’s product.

Even the direct competitors are, however, often overlooked.

The big chemical companies, for instance, despite their careful industry intelligence, are capable of acting as if there were no competitors to worry about.

When in the early fifties the first of the volume plastics, polyethylene, established itself in the market, every major chemical company in America saw its tremendous growth potential.

Everyone, it seems, arrived at about the same, almost unbelievable, growth forecast.

But no one, it seems, realized that what was so obvious to him might not be totally invisible to the other chemical companies.

Every major chemical company seems to have based its expansion plans in polyethylene on the assumption that no one else would expand capacity.

Demand for polyethylene actually grew faster than even the almost incredible forecasts of that time anticipated.

But because everybody expanded on the assumption that his new plants would get the entire new business, there is such over-capacity now that the price has collapsed and the plants are half-empty.

4. Another important corollary is that what the producer or supplier thinks the most important feature of a product to be—what they mean when they speak of its “quality”—may well be relatively unimportant to the customer.

It is likely to be what is hard, difficult, and expensive to make.

But the customer is not moved in the least by the manufacturer’s troubles.

His only question is—and should be: “What does this do for me?”

How difficult this is for businessmen to grasp, let alone to accept, the advertisements prove.

One after the other stresses how complicated, how laborious, it is to make this or that product.

“Our engineers had to suspend the Laws of Nature to make this possible” is a constant theme.

If this makes any impression on the customer, it is likely to be the opposite of the intended one: “If this is so hard to make right,” he will say, “it probably doesn’t work.”

5. The customers have to be assumed to be rational.

But their rationality is not necessarily that of the manufacturer; it is that of their own situation.

To assume—as has lately become fashionable—that customers are irrational is as dangerous a mistake as it is to assume that the customer’s rationality is the same as that of the manufacturer or supplier—or that it should be.

A lot of pseudo-psychological nonsense has been spouted because the American housewife behaves as a different person when buying her groceries and when buying her lipstick.

As the weekly food-buyer for the family, she tends to be highly price-conscious; she deserts the most familiar brand as soon as another offers a “five-cents-off” special.

Of course.

She buys food as a “professional,” as the general home manager.

But who would want to be married to a woman who buys lipstick the same way?

Not to use the same criterion in what are two entirely different roles—and yet both real, rather than make-believe—is the only possible behavior for a rational person.

It is the manufacturer’s or supplier’s job to find out why the customer behaves in what seems to be an irrational manner.

It is his job either to adapt himself to the customer’s rationality or to try to change it.

But he must first understand and respect it.

6. No single product or company is very important to the market.

Even the most expensive and most wanted product is just a small part of a whole array of available products, services, satisfactions.

It is at most of minor interest to the customer, if he thinks of it at all.

And the customer cares just as little for any one company or any one industry.

There is no social security in the market, no seniority, no old-age disability pensions.

The market is a harsh employer who will dismiss even the most faithful servant without a penny of severance pay.

The sudden disintegration of a big company would greatly upset employees and suppliers, banks, labor unions, plant-cities, and governments.

But it would hardly cause a ripple in the market.

For the businessman this is hard to swallow.

What one does and produces is inevitably important to oneself.

The businessman must see his company and its products as the center.

The customer does not, as a rule, see them at all.

How many housewives have ever discussed the whiteness of their laundry over the back fence?

Of all possible topics of housewifely conversation, this surely ranks close to the bottom.

Yet not only do advertisements play that theme over and over again, but soap company executives all believe that how well their soap washes is a matter of major concern, continuing interest, and constant comparison to housewives—for the simple reason that it is, of course, a matter of real concern and interest to them (and should be).

7. All the statements so far imply that we know who the customer is.

However, a marketing analysis has to be based on the assumption that a business normally does not know but needs to find out.

Not “who pays” but “who determines the buying decision” is the “customer.”

The customer for the pharmaceutical industry used to be the druggist who compounded medicines either according to a doctor’s prescription or according to his own formula.

Today the determining buying decision for prescription drugs clearly lies with the physician.

But is the patient purely passive—just the man who pays the bill for whatever the physician buys for him?

Or is the patient—or at least the public—a major customer, what with all the interest in, and publicity for, the wonder drugs?

Has the druggist lost completely his former customer status?

The drug companies clearly do not agree in their answers to these questions; yet a different answer leads to very different measures.

The minimum number of customers with decisive impact on the buying decision is always two: the ultimate buyer and the distributive channel.

A manufacturer of processed canned foods, for instance, has two main customers: the housewife and the grocery store.

Unless the grocer gives his products adequate shelf space, they cannot be bought by the housewife.

It is self-deception on the part of the manufacturer to believe that the housewife will be so loyal to his brand that she would rather shop elsewhere than buy another well-known brand she finds prominently displayed on the shelves.

Which of these two, ultimate buyer or distributive channel, is the more important customer is often impossible to determine.

There is, for instance, a good deal of evidence that national advertising, though ostensibly directed at the consumer, is most effective with the retailer, is indeed the best way to move him to promote a brand.

But there is also plenty of evidence—contrary to all that is said about “hidden persuaders”—that distributors, no matter how powerfully supported by advertising, cannot sell a product that the consumer for whatever reason does not accept.

Who is the customer tends to be more complex and more difficult to determine for industrial than for consumer goods.

Who is the ultimate consumer and who is the distributive channel for the manufacturer of power equipment for machinery: the purchasing agent of the machinery manufacturer who lets the contract; or the engineer who sets the specifications?

The buyer of the completed machine?

While the latter is usually without power to decide from which maker the parts of the machine (e. g., the motor starter and the motor controls) should come, he almost always has power to veto any given supplier.

All three—if not many more—are customers.

Each class of customers has different needs, wants, habits, expectations, value concepts, and so on.

Yet each has to be sufficiently satisfied at least not to veto a purchase.

8. But what if no identifiable customer can be found for a business or an industry?

A great many businesses have no one person or group of persons who could be called their customer.

Who, for example, is the customer of a major glass company which makes everything as long as it is glass?

It may sell to everybody—from the buyer of automobile instrument-board lights to the collector of expensive hand-blown vases.

It has no one customer, no one particular want to satisfy, no one particular value expectation to meet.

Similarly, in buying paper for a package, the printer, the packaging designer, the packaging converter, the customer’s advertising agency, and the customer’s sales and design people, all can—and do—decide what paper not to buy.

And yet none of them makes the buying decision itself.

None of these people buys paper as such.

The decision is made indirectly, through deciding on shape, cost, carrying capacity of the package, graphic appearance, and so on.

Who is actually the customer?

There are two large and important groups of industries in which it is difficult and sometimes impossible to identify the customer: materials industries and end-use supply (or equipment) makers.

Materials industries are organized around the exploitation of one raw material, such as petroleum or copper; or around one process, such as the glassmaker, the steel mill, or the paper mill.

Their products are of necessity material—determined rather than market—determined.

The end-use industries, such as a manufacturer of adhesives-starches, bonding materials, glues, and so on—have no one process or material to exploit.

Adhesives can be made from vegetable matter such as corn or potatoes, from animal fats, and from synthetic polymers furnished by the petrochemical industry.

But there is still no easily identifiable, no distinct customer.

Adhesives are used in almost every industrial process.

But to say—as one would have to say about the steel mill or the adhesives plant—that everyone is his customer, is to say that no one is an identifiable customer.

The answer is not, however, that these businesses cannot be subjected to a marketing analysis.

Rather, markets or end-uses, instead of customers, are the starting point for this analysis in materials and end-use industries.

Materials businesses—steel or copper, for instance—can usually be understood best in terms of markets.

It is meaningful to say, for instance, that a certain percentage of all copper products go into the construction market—though they go to such a multitude of different customers and for such a variety of end-uses that these two dimensions may well defy analysis.

It is meaningful to say that the adhesives all serve one end-use: to hold together the surfaces of different materials, though neither customer analysis nor market analysis may make much sense.

The view from outside has three dimensions rather than one.

It asks not only “Who buys?” but “Where it is bought?” and “What it is being bought for?”

Every business can thus be defined as serving either customers, or markets, or end-uses.

Which of the three, however, is the appropriate dimension for a given business cannot be answered without study.

Every marketing analysis of a business therefore should work through all three dimensions to find the one that fits best.

This, by the way, is why the phrase “customers, markets, end-uses” has appeared so often in the preceding chapters.

Again and again one finds

(1) that a dimension the people in the business consider quite inappropriate—customers or end-uses in a paper company, for instance—is actually highly important; and

(2) that superimposing the findings from the analysis of one of these dimensions on another on g., analysis of a paper company in terms of paper end-uses, paper markets, and paper customers—yields powerful and productive insights.

Even where there is a clearly identifiable customer, one does well to examine the business also in relation to its markets or the end-uses of its products or services.

This is the only way one can be sure of defining adequately what satisfaction it serves, for whom and how.

It is often the only way to determine on what developments and factors its future will depend.

These market realities lead to one conclusion: the most important questions about a business are those that try to penetrate the real world of the consumer, the world in which the manufacturer and his products barely exist.

Knowledge Realities

These examples convey five fundamentals:

1. A valid definition of the specific knowledge of a business sounds simple—deceptively so.

One always excels at doing something one considers so obvious that everybody else must be able to do it too.

The old saying that the erudition a man is conscious of is not learning but pedantry applies also to the specific knowledge of a business.

2. It takes practice to do a knowledge analysis well.

The first analysis may come up with embarrassing generalities such as: our business is communications, or transportation, or energy.

But of course every business is communications or transportation or energy.

These general terms may make good slogans for a salesmen’s convention; but to convert them to operational meaning—that is, to do anything with them (except to repeat them)—is impossible.

On the other extreme, one may come up with a twenty-four volume encyclopedia of the physical sciences as a knowledge-definition plus a complete set of handbooks on all business functions.

It is perfectly true that everyone in a managerial job should know the fundamentals of each business function and of every business discipline.

Every manager should understand the fundamentals of those areas of human inquiry—whether electrical engineering, pharmacology or, in a publishing house, the craft of the novelist—that are relevant to his business.

But no one can excel at universal knowledge—one probably cannot even do moderately well at universal information.

But with repetition the attempt to define the knowledge ‘of one’s own business soon becomes easy and rewarding.

Few questions force a management into as objective, as searching, as productive a look at itself as the question: What is our specific knowledge?

3. Few answers moreover are as important as the answer to this question.

Knowledge is a perishable commodity.

It has to be reaffirmed, relearned, re-practiced all the time.

One has to work constantly at regaining one’s specific excellence.

But how can one work at maintaining one’s excellence unless one knows what it is?

4. Every knowledge eventually becomes the wrong knowledge.

It becomes obsolete.

The question should always arise: What else do we need?

Or do we need something different?

“Have our recent experiences borne out our previous conclusions that this particular ability gives us leadership?” the president of a successful Japanese chemical company asks each of his top men once every six months.

He himself analyzes the performance of each product, in each market and with each important customer, to see whether actual experience is in line with the expectations and predictions of his knowledge analysis.

He asks each of his top men—from research director to controller and personnel man—to do the same analysis.

And he spends one of his quarterly three-day management meetings on knowledge analysis.

He credits his growth—within a decade this formerly limited and fairly small company has become one of the world’s leading producers in a major field—to reviewing knowledge effectiveness and knowledge needs.

5. Finally, no company can excel in many knowledge areas.

Most companies—like most people—find it hard enough to be merely competent in a single area.

This, of course, means that most businesses remain marginal and just manage to hang on.

The figures amply confirm this.

Out of each hundred businesses started, seventy-five or so die before their fifth birthday with management failure as the leading cause of death.

A business may be able to excel in more than one area.

A successful business has to be at least competent in a good many knowledge areas in addition to being excellent in one.

And many businesses have to achieve beyond the ordinary in more than one area.

But to have real knowledge of the kind for which the market offers economic rewards requires concentration on doing a few things superbly well.

Making the Future Today

We know only two things about the future:

It cannot be known.

It will be different from what exists now and from what we now expect.

These assertions are not particularly new or particularly striking.

But they have far-reaching implications.

1. Any attempt to base today’s actions and commitments on predictions of future events is futile.

The best we can hope to do is to anticipate future effects of events which have already irrevocably happened.

2. But precisely because the future is going to be different and cannot be predicted, it is possible to make the unexpected and unpredicted come to pass.

To try to make the future happen is risky; but it is a rational activity.

And it is less risky than coasting along on the comfortable assumption that nothing is going to change, less risky than following a prediction as to what “must” happen or what is “most probable.”

Business these last ten or twenty years has accepted the need to work systematically on making the future.

But long-range planning does not—and cannot—aim at the elimination of risks and uncertainties.

That is not given to mortal man.

The one thing he can try is to find, and occasionally to create, the right risk and to exploit uncertainty.

The purpose of the work on making the future is not to decide what should be done tomorrow, but what should be done today to have a tomorrow.

The deliberate commitment of present resources to an unknown and unknowable future is the specific function of the entrepreneur in the term’s original meaning.

J. B. Say, the great French economist who coined the word around the year 1800, used it to describe the man who attracts capital locked up in the unproductive past (e. g., in marginal land) and commits it to the risk of making a different future.

English economists such as Adam Smith with their focus on the trader saw efficiency as the central economic function.

Say, however, rightly stressed the creation of risk and the exploitation of the discontinuity between today and tomorrow as the wealth-producing economic activities.

Now we are learning slowly how to do this work systematically and with direction and control.

The starting point is the realization that there are two different—though complementary approaches:

• Finding and exploiting the time lag between the appearance of a discontinuity in economy and society and its full impact—one might call this anticipation of a future that has already happened.

• Imposing on the as yet unborn future a new idea which tries to give direction and shape to what is to come.

This one might call making the future happen.

The Future That Has Already Happened

There is a time lag between a major social, economic, or cultural event and its full impact.

A sharp rise or a sharp drop in the birthrate will not have an effect on the size of the available labor force for fifteen to twenty years.

But the change has already happened.

Only catastrophe—destructive war, famine, or pandemic—could prevent its impact tomorrow.

These are the opportunities of the future that has already happened.

They might therefore be called a potential.

But unlike the potential discussed in the last chapter, the future that has already happened is not within the present business; it is outside: a change in society, knowledge, culture, industry, or economic structure.

It is, moreover, a major change rather than a trend, a break in the pattern rather than a variation within it.

There is, of course, considerable uncertainty and risk in committing resources to anticipation.

But the risk is limited.

We cannot really know how fast the impact will occur.

But that it will occur we can say with a high degree of assurance; and we can, to a useful extent, describe it.

There is a lot we cannot anticipate regarding the impact of a change in birthrate on the labor force: how large a proportion of the women will be in the labor force, for instance; how many of today’s young children will stay in school well beyond age fourteen or sixteen; where the future jobs will be, and how many; and so forth.

But one can say with assurance: “This is the largest the labor force can be a decade or two hence—for to be in it a person has to have been born by now.”

One can equally say: “That Latin America in the last generation has changed from a rural to an urban society is a fact—and it is bound to have long-range impact.”

Fundamental knowledge has to be available today to be able to serve us ten or fifteen years hence.

In the mid-nineteenth century one could only speculate about the consequences for the economy of Michael Faraday’s discoveries in electricity.

A good many of the speculations were undoubtedly wide of the mark.

But that this breakthrough into an entirely new field of energy would have major impact could be said with some certainty.

Major cultural changes too operate over a fairly long period.

This is particularly true of the subtlest but most pervasive cultural change: a change in people’s awareness.

It is by no means certain that the underdeveloped countries will succeed in rapidly developing themselves.

On the contrary, it is probable that only a few will succeed, and that even these few will go through difficult times and suffer severe crises.

But that the peoples of Latin America, Asia, and Africa have become aware of the possibility of development and that they have committed themselves to it and to its consequences is a fact.

It creates a momentum that only disaster could reverse.

These countries may not succeed in industrializing themselves.

But they will, for a historical period at least, give priority to industrial development—and hard times may only accentuate their new awareness of the possibility of, and need for, industrial development.

Similarly, it would take a bold man to predict how fast the Negro will gain complete equality in American society.

But that, as a result of the events of 1962 and 1963, there is a new awareness of race relations in the United States on the part of Negro and white alike; above all, that the “submissive Negro” has become a thing of the past, at least as far as the young people are concerned, is a fact that already happened.

It is the kind of fact that is irreversible.

It will have impact; the only question is how soon.

Industry and marketing structures too are areas where the future may have already happened—but where impacts are not yet accomplished.

The Free World economy may collapse again into economic nationalism and protectionism.

The tremendous scope and impact of the movement toward a truly international economy in the nineteen fifties and nineteen sixties may have created so much stress and strain (e. g., political pressure from over-protected farmers) that a severe reaction will set in.

But the businessman’s awareness of the existence and extent of the international economy should persist.