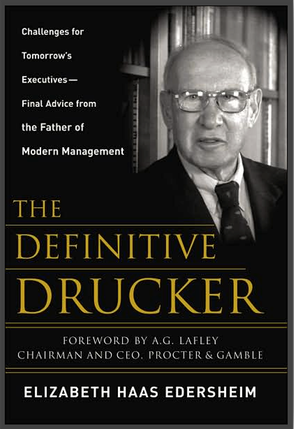

The Definitive Drucker

Amazon link: The Definitive Drucker: Challenges For Tomorrow's Executives — Final Advice From the Father of Modern Management

Table of contents

“We need a new

theory of management.

The assumptions

built into business today

are not accurate.” — Peter Drucker

For sixteen months before his death, Elizabeth Haas Edersheim was given unprecedented access to Peter Drucker, widely regarded as the father of modern management.

He liberated people from the prisons of the past

At Drucker’s request, Edersheim, a respected management thinker in her own right, spoke with him about the development of modern business throughout his life—and how it continues to grow and change at an ever-increasing rate.

The Definitive Drucker captures his visionary management concepts, applies them to the key business risks and opportunities of the coming decades, and imparts Drucker’s views on current business practices, economic changes, and trends—many of which he first predicted decades ago.

It also sheds light onto issues such as why so many leaders fail, the fragility of our economic systems, and the new role of the CEO.

Managing in the Next Society

Drucker’s insights are divided into five main themes that the modern organization needs to, as Drucker would say, “create tomorrow” by:

Connecting with customers Connecting with customers

Innovating without abandoning what works Innovating without abandoning what works

Developing lasting partnerships Developing lasting partnerships

Creating and retaining knowledge workers Creating and retaining knowledge workers

Establishing disciplined decision making Establishing disciplined decision making

Drucker’s penetrating questions, posed to those seeking his advice, helped business, corporate, and political leaders throughout the 20th century to see their work in a new perspective, and create phenomenal innovation.

Edersheim’s extensive interviews with some of these luminaries, including Warren Bennis, Ram Charan, Bill Gates, George Gallup, Jr. and A.G. Lafley offer compelling commentary on Drucker’s vast influence.

Delivering keen analysis and revealing insights into business, The Definitive Drucker is a celebration of this extraordinary man and his life’s work, as well as a unique opportunity to learn from Drucker’s final business lessons how to strategize, compete, and triumph in any market.

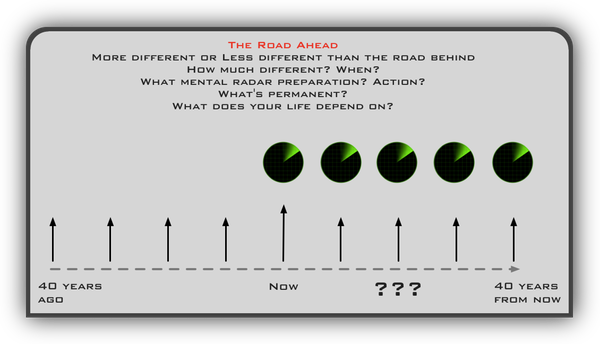

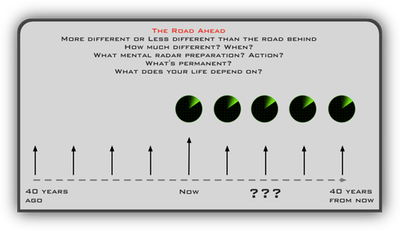

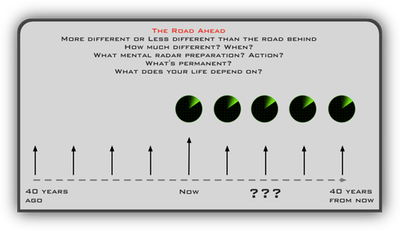

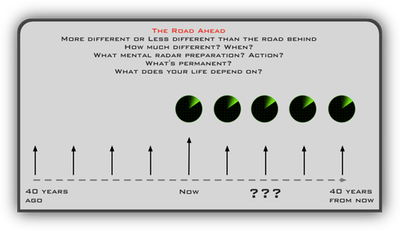

Every thing below

will have to be worked on

at multiple points in time.

Waiting until there is an obvious need is a recipe for trouble.

“It’s not the will to win,

but the will to prepare to win

that makes the difference.” — Bear Bryant

“If You Keep Doing What Worked in the Past

You’re Going to Fail” — A Class With Drucker

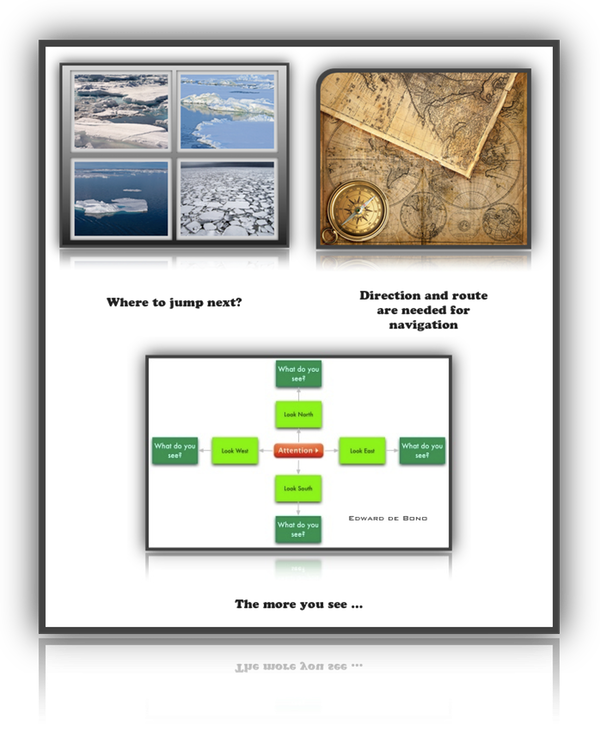

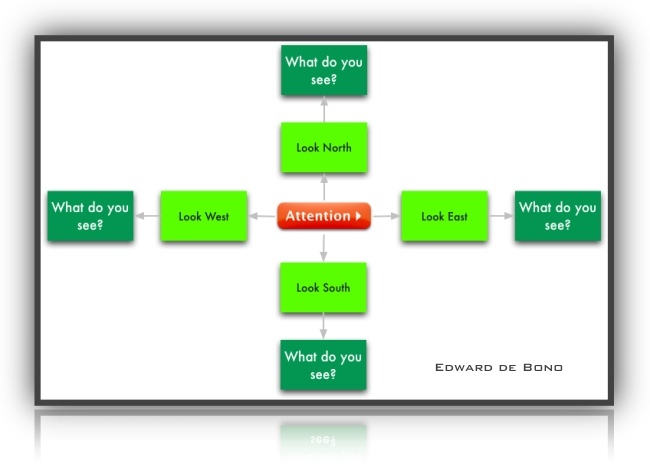

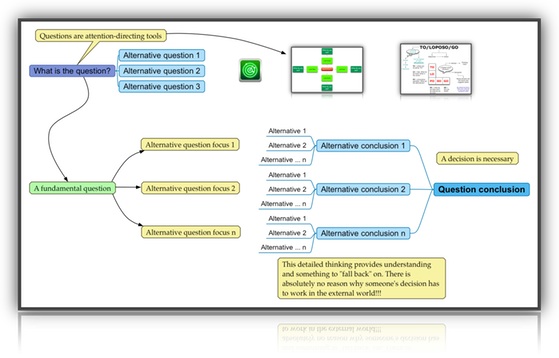

“To know something,

to really understand something important,

one must look at it from sixteen different angles.

People are perceptually slow,

and there is no shortcut to understanding;

it takes a great deal of time.” read more

What executives should remember and

follow links to Drucker on Asia

Contents of The Definitive Drucker

-

Foreword to the Paperback Edition

-

Introduction to the Paperback Edition

-

Foreword by A.G. Lafley Chairman, President, and CEO P&G

-

Introduction by Elizabeth Haas Edersheim

-

Doing Business in the Lego World

-

The Customer: Joined at the Hip

-

Medtronic

-

Connecting With Your Customer: Four Drucker Questions

-

Who Should Be Considered A Customer?

-

Ideas In Action: Shadow Customers

-

Customer Versus Competitor?

-

Who Is Not Your Customer?

-

Which Of Your Current Noncustomers Should You Be Doing Business With?

-

What Does Your Customer Consider Value?

-

Does Your Customer’s Perception Of Value Align With Your Own?

-

How Do Connectivity And Relationships Influence Value?

-

Which Customer Wants Remain Unsatisfied?

-

What Are Your Results With Customers?

-

How Are You Measuring Your Outside Results?

-

How Are Outsiders Measuring And Sharing Results And Information …

-

Are You Fully Leveraging The Information Your Results Provide?

-

Are You Honest And Socially Responsible In Presenting Your Results?

-

Does Your Customer Strategy And Your Business Strategy Work Together?

-

Procter & Gamble

-

The Grandfather Of Marketing

-

According to Harvard professor and business writer Theodore Levitt, “Peter Drucker created and publicized the marketing concept.”

-

In an essay on Drucker’s importance to marketing, Arnold Corbin, former professor of marketing at New York University, states that despite being essentially a management writer, Drucker “has probably contributed more to the development and understanding of marketing than any ‘marketing man.’”

-

Conclusion

-

Innovation and Abandonment

-

Creating Your Tomorrow: Four Drucker Questions

-

What Do You Have To Abandon To Create Room For Innovation?

-

If You Weren’t In This Business Today, Would You Invest The Resources To Enter It?

-

What Unconscious Assumptions Limit Your Innovative Thinking?

-

Are Your Highest-Achieving People Assigned To Innovative Opportunities?

-

Do You Systematically Seek Opportunities

-

Do You Use A Disciplined Process For Converting Ideas Into Practical Solutions?

-

Does Your Innovation Strategy Work With Your Business Strategy?

-

What Is Your Company’s Target Role In Defining New Markets?

-

Do Your Opportunities Fit With Your Business Strategy?

-

Are You Allocating Resources Where You Want To Be Making Bets?

-

How Innovation Enables GE’s Longevity And Valuation

-

Making Innovation Everyone’s Business

-

In Contrast To GE: Siemens AG

-

Different Cultures

-

Differing Results

-

Conclusion

-

Collaboration and Orchestration

-

Peter’s vision of collaboration

-

The Power Of Collaboration

-

Collaboration And Orchestration: Three Drucker Questions

-

Three Groups of Drucker Questions

-

Goals

-

Structure

-

Operate and Orchestrate

-

Some unmet needs are simply not possible without collaboration

-

Barriers of the Prevailing Academic Model

-

Barriers between the Private-Sector and the Academic World

-

Dell Example

-

Example from Developing Countries

-

Identify your “Front Room” and Outsource the Rest

-

Myelin Repair Foundation Approach

-

Linux Example

-

Toshiba Example

-

More Drucker Thoughts

-

Create A Living Business Plan

-

Structure Communications For Agile Decision Making

-

Track Progress As Measured By Expected Results

-

Evolving Business Models

-

Adaptation and Orchestration at LM Ericsson

-

Learning the Nuances of Working with Japanese Partners

-

Conclusion

-

People and Knowledge

-

Drucker’s People First Thinking

-

Feedback from Drucker Clients

-

Alcoa and People (example)

-

Drucker’s Basic People Views

-

Drucker listed five rules for making hiring decisions:

-

Look at a number of potentially qualified people

-

Think hard about what each candidate brings to the position and the organization

-

Have a variety of people get to know the candidate as a person

-

Discuss each of the candidates with several people who have worked with them

-

After the hire, follow up to make sure the appointee understands the job

-

Investing In People And Knowledge: Five Drucker Questions

-

Who Are The Right People For Your Organization?

-

Are You Providing Your People With The Means To Make Their Maximum Contribution To The Organization’

-

Is There A Clear Mission And Direction That Builds Commitment?

-

Are People Given Autonomy And Support?

-

Are You Playing To People’s Strengths Rather Than Managing Around Their Problems?

-

Do Your Structure And Processes Institutionalize Respect For And Investment In Human Capital?

-

Do You Systematically Match Strengths With Opportunities?

-

Do Your Structure And Processes Maximize The Knowledge Worker’s Contribution And Productivity?

-

Do You Systematically Develop Employees?

-

Is Knowledge And Access To Knowledge Built Into Your Way Of Doing Business?

-

Is Knowledge Built Into Your Customer Connection?

-

Is Knowledge Built Into Your Innovation Process?

-

Is Knowledge Built Into Your Collaborations?

-

Is Knowledge Built Into Your People And Knowledge Management?

-

Electrolux example: Using Talent Management To Accelerate Strategic Change

-

Knowledge, Information, People and Organizations

-

How People Make The Difference At Edward Jones

-

Google’s 10 BULL SHIT Rules For Knowledge Workers

-

1. Hire by committee

-

2. Cater to their every need

-

3. Pack them in

-

4. Make coordination easy

-

5. Eat your own dog food

-

6. Encourage creativity

-

7. Strive to reach consensus

-

8. Don’t be evil

-

9. Data drives decisions

-

10. Communicate effectively

-

Conclusion

-

Decision Making: The Chassis That Holds the Whole Together (about Decisions)

-

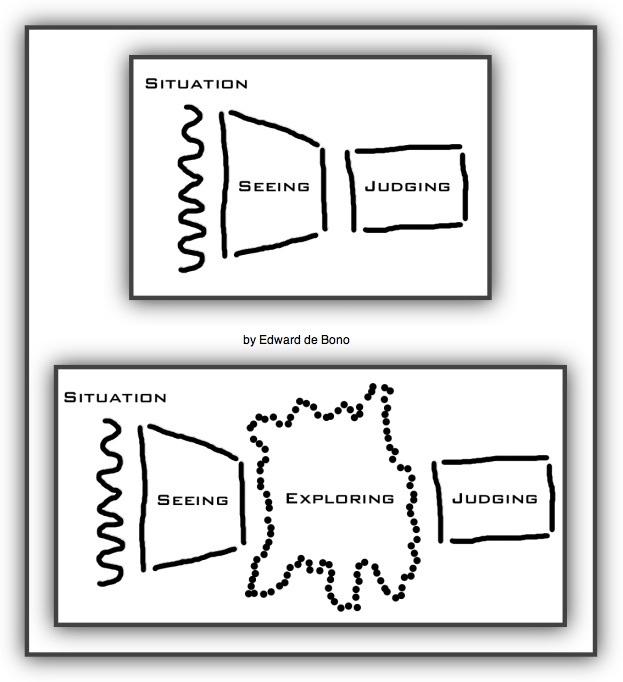

Examining/Exploring the Strategic and Unfolding Landscape

-

Decision Making: The Right Risks

-

Decision Making: Four Drucker Questions

-

Have you built in time to focus on critical decisions—have you lightened your load?

-

Does your culture support making the right decision with ready contingency plans?

-

What’s The Real Issue?

-

What Specifications Must The Solution Meet?

-

Have You Fully Considered All The Alternative Solutions?

-

Guidelines for Choosing Alternatives

-

Is The Organization Willing To Commit To The Decision Once It Is Made?

-

As Decisions Are Made, Are Resources Allocated To “Degenerate Into Work”

-

The Decision Process

-

Toyota Example

-

Decision Making By Alfred Sloan

-

Conclusion

-

The Twenty-First-Century CEO

-

Endnotes

-

Books By Peter F. Drucker and below

-

Acknowledgments

Be aware that the author’s world view

is not nearly as far-sighted, strategic or effective as Drucker’s.

In spite of her efforts she maintains a day-to-day, operational view

because that’s how she started out.

It is very hard to do a brain erase.

Foreword to the Paperback Edition

Peter Drucker, who was mostly right about everything, was dead wrong on one point.

Two years before his death in 2005, he had volunteered to speak directly to the students of the business school that bore his name at the Claremont Graduate School.

They were upset, even marching outside the dean's office toting placards decrying a decision to put another name on the Drucker School to gain a $20 million gift.

"I consider it quite likely that three years after my death my name will be of absolutely no advantage," he told them.

"If you can get 10 million bucks by taking my name off, more power to you."

Drucker underestimated the enduring nature of his contributions to management and society as the 10th anniversary publication of The Definitive Drucker clearly demonstrates.

In fact, if ever there was a time when a voice of reason was sorely needed, it would be right now and it would be none other's than Peter Drucker's.

At a moment when the world seems ever more fractured and polarized, Drucker's thoughtful perspective would be calming if not reassuring.

Luckily, the book in your hands is the next best thing: The Definitive Drucker is a master work by Elizabeth Haas Edersheim that smartly distills the wisdom of the most enduring management thinker of all time.

First, a confession.

As much as I admired Peter, I often felt many of his books were sometimes difficult to get through.

They were profoundly thoughtful but also often dense.

What Edersheim has done in what is now a classic work is extract the gems from Drucker's prodigious life with a clarity and succinctness that makes his contributions all the more accessible.

So if you want to know what Drucker thought about management or knowledge, the customer or people, innovation or collaboration, these pages bring his ideas alive and prove how relevant they are yet again.

As to why Drucker matters, more than ten years after he died in his sleep eight days shy of his 96th birthday, it's simple — his teachings form a blueprint for every thinking leader.

In a world of quick fixes and glib explanations, a world of fads and simplistic PowerPoint lessons and tweets, he understood that the job of leading people and institutions is filled with complexity.

He taught generations of managers the importance of picking the best people, of focusing on opportunities and not problems, of getting on the same side of the desk as your customer, of the need to understand your competitive advantages and to continue to refine them.

He believed that talented people were the essential ingredient of every successful enterprise.

The Definitive Drucker is definitive on these points.

He was the guru's guru, a sage, kibitzer, doyen, and gadfly of business, all in one.

He had moved fluidly among his various roles as journalist, professor, historian, economics commentator, and raconteur.

Over his 95 prolific years, he had been a true Renaissance man, a teacher of religion, philosophy, political science, and Asian art, even a novelist.

But his most important contribution, clearly, was in business.

What John Maynard Keynes is to economics or W. Edwards Deming to quality, Drucker is to management.

Drucker made observation his life's work, gleaning deceptively simple ideas that often elicited startling results.

Shortly after Jack Welch became CEO of General Electric in 1981, for example, he sat down with Drucker at the company's New York headquarters.

Drucker posed two questions that arguably changed the course of Welch's tenure: "If you weren't already in a business, would you enter it today?" he asked.

"And if the answer is no, what are you going to do about it?"

Those questions led Welch to his first big transformative idea: that every business under the GE umbrella had to be either number 1 or number 2 in its class.

If not, Welch decreed that the business would have to be fixed, sold, or closed.

It was the core strategy that helped Welch remake GE into one of the most successful American corporations of the past 25 years.

Drucker's work at GE is instructive.

It was never his style to bring CEOs clear, concise answers to their problems but rather to frame the questions that could uncover the larger issues standing in the way of performance.

"My job," he once lectured a consulting client, "is to ask questions.

It's your job to provide answers."

While sometimes frustrating for the impatient manager, Drucker's approach was enormously helpful to those he counseled largely because he was way ahead of the curve on major trends.

His mind was an itinerant thing, able, in minutes, to wander through a series of digressions until finally coming to some specific business point.

He could unleash a monologue that would include anything from the role of money in Goethe's Faust to the story of his grandmother who played piano for Johannes Brahms, yet somehow use it to serve his point of view.

Everyone who knew him has a story or two about him, for sure.

I first met Drucker in 1985 when I was scrambling to master my new job as management editor at Business Week.

He invited me to Estes Park, Colorado, where he and his wife often spent summers in a log cabin, part of a YWCA camp.

I remember him counseling me to drink lots of water, to ingest a megadose of vitamin C, and to take it easy to adjust to the high altitude.

I spent two days getting to know Drucker and his work.

We had breakfast, lunch, and dinner together.

We hiked the trails of the camp.

And, I became intimately familiar with his remarkable story.

Toward the end of his life, I met with him several times, just as Edersheim did for 16 months before his death.

During our last meeting in April of 2005 — seven months before he passed on November 11th — Drucker seemed unusually frail and tired in black cotton slippers and socks that barely covered his ankles.

I asked Drucker what he had been up to lately.

"Not very much," he replied.

"I have been putting things in order, slowly.

I am reasonably sure that I am not going to write another book.

I just don't have the energy.

My desk is a mess, and I can't find anything."

I almost felt guilty for having asked the question, so I praised his work, the 39 books, the countless essays and articles, the consulting gigs, his widespread influence on so many of the world's most celebrated leaders.

But he was agitated, even dismissive, of much of his accomplishment, not in much of a mood to ponder his legacy.

I pressed the nonagenarian for more reflection, more introspection.

"Look," he sighed, "I'm totally uninteresting.

I'm a writer, and writers don't have interesting lives.

My books, my work, yes.

That's different.

What I would say is I helped a few good people be effective in doing the right things."

It's something we all need to learn again.

John A. Byrne

Former Editor at Business Week

Founding Member of the Board of the Drucker Institute

Founder and Chairman of C-Change Media Inc.

Introduction to the Paperback Edition

I first met Peter F. Drucker in the winter of 1980 and was both honored and daunted when 23 years later, he asked me to write a book about how his ideas could be used in the twenty-first century.

By then, Peter himself had written 39 books.

And although by that time three books about Drucker had been published, none addressed how to put the observations, wisdom, principles, and practices of "the father of modern management" to use in this new century.

That was what Peter was after, and that's what we set out to do.

I spent the next two years interviewing Peter and many of the legendary chiefs of industry, finance, nonprofit groups, and countries he had influenced.

Our last conversation took place in the fall of 2005, a month before his death.

As I sensed that Peter's last days were approaching, I also became more keenly aware of how desperately America and other countries needed business and political leaders to think as Peter F. Drucker always had: with discipline, ethics, responsibility, and reflection; and with the individual, the organization, and society working together.

On the day he died, his wife, Doris, called me.

She didn't have to say a word — I instantly knew he was gone as I blurted out, "Oh, Doris, his ideas will live on!"

And as we both began to cry, I knew that what I'd just heard myself say out loud for the first time was absolutely true.

Peter continues to be widely quoted and referenced.

The annual Drucker Forum attracts leading thinkers from around the world to discuss a selected Drucker topic, such as growth and prosperity.

Since The Definitive Drucker's first publication, I have continually heard from readers all over the world thanking me for how helpful the book has been and how Peter's discipline has helped them elevate their leadership.

A woman in Saudi Arabia recently wrote, "It was the education that I never had and needed to grow my business."

And when two students at Copenhagen Business School recently interviewed me as part of their thesis work, they asked stunningly perceptive questions that Drucker himself surely would have appreciated.

Last year I was asked to write a blog for the Institution on an education book that had defined the role of education in building Druckerian thinkers for tomorrow.

Day after day, I see Peter's inspiration evidenced by leading enterprises, the students I teach, and the clients I have the privilege of working with.

Now, 10 years after the hardcover of The Definitive Drucker was published, our world has crossed another, as Peter might say, historic divide, characterized by the sheer quantity, rapidity, and breadth of changes our social, political, and economic landscapes have undergone alongside the profound leap that technology has taken.

It is undoubtedly a new world, and Peter had this to say about organizations in new worlds:

"If nothing changes, we risk atrophying in our irrelevancy.

But, if everything changes, we risk losing ourselves in ineffective chaos."

The leaders of the institutions most successfully crossing this historic divide appear to be steeped in Peter.

When Satya Nadella stepped in as CEO of Microsoft, his first act was to rewrite the mission statement with "Drucker rules" — centering on the customer instead of Microsoft and which could fit on a T-shirt.

He encouraged people to find ways to connect with customers and do the impossible for them.

Jeff Immelt, GE's CEO, has spent his career inside GE — a company where Peter worked closely with the previous four CEOs, building a culture that continually challenges assumptions and plays to its strengths.

Immelt often asks Drucker's first question: What needs to be done?

Under his leadership GE has refocused on the "internet of industry," supporting GE's being in ahead of other industry policy makers when it comes to climate change.

Immelt, who embraces Drucker's value of dissent, is not afraid of taking a position on this that differs with that of the current President of the United States, and he encourages dissent inside the corporation.

Zhang Ruimin, the CEO of Haier, the leading global appliance company, has studied Peter since he was a teenager and centers virtually all of Haier's corporate training on Peter F. Drucker.

The leaders of new institutions innovating in the new world appear to have an uncanny connection with Peter.

Facebook's talent group is steeped in the Drucker principles.

Spotify's CEO quotes Peter Drucker almost daily.

The leaders at Blast refer back to Peter as they make every decision.

Peter F. Drucker resonates with social sector leaders as well.

Wendy Kopp is one example.

Taking on one of the most intransigent sectors, she founded Teach for America and is now scaling social changes to countries around the world, referring to Drucker's lessons along the way.

While Peter was intensely interested in management as a profession, he believed that corporations and social enterprises-fast emerging as our most important institutions-had to be both effective and responsible.

Otherwise, he warned, we won't have a functioning society.

To be effective, Peter emphasized, we need to embrace new realities while holding onto principles and purpose.

The first corporation he stepped inside of and wrote about was General Motors.

Its current CEO could, I believe, learn much about leading GM tomorrow from the book Peter wrote about Alfred Sloan's leading it in the 1940s.

As my young Sports Management master's degree students at New York University learn about hands-on consulting, I've seen them practice some of Drucker's principles while helping their clients — for instance, by challenging their clients' assumptions and helping them practice abandonment.

For example, for many decades (maybe even since the gory displays at the Roman Colosseum), sports revenue has come from people sitting in stadiums and then in front of televisions.

One student team proved to its sports-promoter client that this is no longer true-that, for example, more people had tuned into the League of Legends World Championship on mobile devices than had watched the 2016 Super Bowl on television.

This revelation spurred the client to rethink his revenue model.

A decade ago, Peter F. Drucker envisioned this divide I have been discussing here when he said, "We will not know the impact of the Internet until we have observed how behavior changes."

Well, we can clearly observe those behavior changes now, and my students who have embraced Drucker's principles of challenging assumptions and abandoning outworn tenets are helping their clients by pointing them out.

I am not at all surprised by the continuing relevance of Drucker today.

He might, however, be more surprised than I. He had a certain humility, which especially struck me one day as we talked in his home office in the fall of 2005.

In his famous Austrian accent he told me he had no illusions about his legacy; in essence, he felt he would be lucky that if in 10 years he was still footnoted in some management and social science literature, as he believed there were certainly more important, impactful contributions than his.

He pointed to the example of his friend Francis Crick, who codiscovered the double helix structure of DNA.

But, Peter was wrong about his legacy.

Peter F. Drucker not only saw what management and leadership of the future would be and require, he also left us the tools to get there, just as his friend Crick gave us tools for modern biotechnology and a future understanding of the mind and consciousness.

Peter's words are certainly still relevant — even critical — today, as we have crossed this divide, have Facebook and Twitter in our daily lives, and see our businesses wrestling with big data algorithms that try to predict consumers' behavior, artificial intelligence, and all the rest.

The challenge of the social sector and the information sector working together has never been more relevant.

And the challenge of making business more productive and more humane certainly has never been more important.

For the sake of the future of our economy, our community, and our society, I believe every thinking manager needs to be familiar with Drucker's discipline of thought and how to put his principles and practices into immediate motion to solve twenty-first century management challenges.

"There is nothing more important than the future impact of decisions we make today."

When I finished writing this book, I knew Drucker's lessons would apply far into the future.

I am still amazed at his prescience.

Knowing and studying Peter F. Drucker changed me: how I work, how I think, the questions I ask.

Perhaps most important, Peter made me appreciate the value of context, reflection, and adopting a Druckerian perspective.

Whether you are a seasoned practitioner or among the new generation of aspiring leaders, I hope reading this paperback edition of The Definitive Drucker will change you for the better, too.

Foreword by A.G. Lafley Chairman, President, and CEO P&G

I did not realize it at the time, but I grew up with Peter Drucker.

My father spent 25 years in management at GE, and another decade at Chase Manhattan.

He met Peter at GE's Crotonville facility in the 1950s and always had Drucker's books on his bookshelf.

Though I had no interest in business as a high school or undergraduate student, I flipped through my father's books—Drucker classics such as The Effective Executive and The Practice of Management.

Later, when I was in the U.S. Navy, I grew more interested in business while running service and retail operations at a U.S. airbase in Japan, and returned to those and other classics.

Slowly but surely, I was becoming a Drucker student.

Regrettably, I did not take the initiative to meet Peter until 1999.

P&G was in the midst of major strategic change and arguably the biggest organizational transformation in its 162-year history.

I was then responsible for P&G's North America region, the big home market, and for P&G's new global beauty business.

I called Peter and asked if he would meet with me.

He agreed, and four decades after he and my father had talked at Crotonville, I sat with Peter in his modest Claremont, California, home, talking about a world he had been thinking about for nearly a half-century.

I had hoped for one hour of his time.

We talked for two.

Then when my wife, Margaret, arrived to pick me up, she came in and we all sat and talked for another two hours.

It was like drinking from a fire hose.

For every question I posed, Peter had one or two more things to think about.

Persistently, he urged me to choose, to focus on the few right strategies and decisions that would make the greatest difference.

He challenged me to understand the unique leadership challenges of managing an organization of knowledge workers.

That exhilarating first conversation provided the themes Peter and I returned to for the next six years:

- how to unleash the creativity and productivity of knowledge workers;

- how to create free markets for ideas and innovation inside and outside a company such as P&G;

- how to build the organizational agility and flexibility to respond to and lead change.

Later, we began a conversation about another subject on which he was focused in the last years of his life: the work of the CEO.

As I've looked back on these conversations and countless hours reading Peter's books and articles, I've thought about what made him so extraordinary.

For me, it comes down to five things.

First and foremost, Peter's basic rule was the importance of serving consumers.

As he liked to say, "The purpose of a business is to create and serve a customer."

Plain and simple.

At P&G, we have translated this principle into respect for the consumer as boss.

Consumer-driven strategy, innovation, and leadership are cornerstones of P&G's success and a reflection of the influence Peter has had on our company.

Second, Peter insisted on the practice of management.

He had little patience for detached theory or abstract plans.

"Plans are only good intentions unless they immediately degenerate into hard work," he wrote.

He and I readily agreed that execution is the only strategy customers or competitors ever see.

I always came away from our conversations with clear, fresh insights that I could apply to P&G's business and organization almost immediately.

But Peter was not a single-minded evangelist for the virtue of execution.

He believed in the power of strategic ideas and making clear choices.

He said, "From quiet reflection will come even more effective action."

His ability to balance action and reflection is what makes his ideas so practical and so enduring.

The third characteristic that made Peter extraordinary was his gift for reducing complexity to simplicity.

His curiosity was insatiable, and he never stopped asking questions.

He called himself a "social ecologist" because he drew from history, art, literature, music, economics, anthropology, sociology, and psychology.

From these many sources of inspiration came the clear questions and simple Drucker insights that lit the road to action: "Management is doing things right; leadership is doing the right things."

"The only way you can manage change is to create it."

"The marketer is the consumer's representative."

His most enduring gift to future generations is that he taught so many others how to ask the right questions.

The fourth defining Drucker strength was his focus on the responsibility of leaders.

Late in his life, he sharpened this focus on the responsibility of CEOs in particular.

"The CEO," he said, "is the link between the inside, where there are only costs, and the outside, which is where the results are."

For many reasons, business organizations become inwardly focused.

Their business and financial measures are internal.

Even if they have external metrics, those measures are often given lower priority because they don't drive short-term financial performance or because they are less precise and more qualitative.

Peter argued that the CEO is in a unique position to balance this inward focus.

The CEO has primary responsibility for bringing the outside in, for ensuring that the organization understands the views of the market, current and potential customers, and competitors.

The fifth and most important of Peter's many attributes was his humanity.

He treated everyone with deep respect.

"Management is about human beings," he wrote.

"Its task is to make people capable of joint performance, to make their strengths effective and their weaknesses irrelevant."

He noted that business and other institutions are "increasingly the means through which individual human beings find their livelihood and their access to social status, to community, and to individual achievement and satisfaction."

While he did not suggest that businesses exist to supply jobs, he argued that managers have a fiscal, societal, and moral responsibility to ensure that jobs are fulfilling and individuals are able to contribute as fully as they can.

I could not agree more.

The most important thing I try to do as CEO is to inspire leaders and unleash the creativity and productivity of P&G's 135,000 knowledge workers.

Humanity infused everything Peter wrote and said.

He was a force for good in the world.

He received the U.S. Medal of Freedom because his management thought, beginning with Concept of the Corporation, helped develop free societies of organizations more productive than dictatorships of the left or right.

This is his greatest contribution.

Peter Drucker was one of a kind.

He was relentlessly focused on the promise of the future and the potential of individuals.

It is entirely fitting that one of his final requests was for a biography of his ideas rather than of his life.

Liz Edersheim has fulfilled this request with The Definitive Drucker.

She has captured not only the essence of Drucker's 39 books and seven decades of discovery and insight, but also the essence of Peter Drucker the man—the wise, funny, insightful, humble teacher who sat with so many of us in his living room asking questions and patiently giving us the time to catch up to where he had already leaped, the man who helped us see what he always described as "visible, but not yet seen."

Through his example and his ideas, Peter will continue to be a force for good in the world for generations to come.

A.G. Lafley Chairman, President, and CEO P&G Cincinnati, Ohio September 6, 2006

I was tempted, not to mention flattered, but commitments ricocheted through my head: In the next few weeks, I had to fly to Brussels for a global meeting at Avon Products, ride in a Starbucks delivery truck through downtown Manhattan at dawn observing the stores from a logistical perspective, and meet with senior pharmaceutical executives in New Jersey to discuss a new packaging format that could help patients remember to complete prescriptions.

But this was Peter Drucker, and he was 94.

It might be the last book he worked on.

I told him I needed to think about it.

At the time, several ideas were coalescing in my mind about how management can best step up to the scary and exhilarating challenges of the twenty-first century.

As a consultant, I work with clients in businesses ranging from chocolates to athletic gear, from diesel engines to computer chips.

Much of what I do professionally is based on Drucker’s take-home pointers about focusing on results and how to be effective.

I am also the mother of two teenagers, and even in that realm his books offer good advice.

My kids shrug their shoulders whenever I trot out my favorite expression, which comes right from Drucker: “Don’t confuse motion with progress.”

I have been working with managers in a dozen industries for over 25 years and have recently seen their struggles intensify as the traditions of the business world are being upended.

Changing customers, changing technology, and changing ways of doing and even defining business are jolting these companies to the core and often challenging their very survival.

When I started as a consultant at McKinsey & Company in the late 1970s, I worked with midwestern companies whose survival was being challenged by Japanese competitors with their lower-cost cars, televisions, and machine tools.

By the mid-1980s, my clients were consumer goods companies that were struggling to meet the demanding requirements of an enterprise that my friends in New York had barely heard of—an Arkansas company by the name of Wal-Mart.

In the late 1980s, I started my own consulting firm and worked primarily with leveraged buyout companies (LBOs) that had paid too much for acquisitions and needed to drastically improve the economics of the companies in their portfolios.

It was here I learned the expression, “The sins of omission are greater than the sins of commission.”

At my firm, we continually tried ideas to test their viability rather than be paralyzed by fear of failure.

As I later learned, this was very much a Drucker thing to do.

In the early 1990s, almost overnight my client list became crowded with electronics companies and medical equipment companies.

They were losing out to Asian and other competitors that churned out cheaper and cheaper knockoffs.

Throughout all those years we didn’t know how lucky we were.

We could look inside a company, study the customers, and reinvent the business.

We could often simply research other industries and top-flight companies to get ideas.

For example, with Sealy Mattress, an overpriced LBO, we could pull $50 million out of cost and guarantee next-day delivery to retailers, fundamentally changing the retailers’ need for inventory.

With Motorola, we could connect with police stations and work with UPS to repair police mobile radios and return them within 24 hours.

But then the world got a lot more complicated.

I began advising one company after another that it had to completely rethink its style and its core practices or else it would become uncompetitive and destroy tremendous shareholder value.

There were no natural solutions or approaches to follow.

Management had to take risks.

Huge risks.

Doing nothing was an even bigger risk.

At the time of Drucker’s call, I was working with three clients, and all three needed a dose of Drucker.

The first, a New England university hospital, was struggling with the decision to install a wireless network that would enable interns to swap patients’ medical records on their laptop computers, speeding up the bureaucratic process and eliminating paper shuffling.

The system had another benefit: It would qualify the university for more Medicare and Medicaid payments.

But it contradicted everything hospital administrators held sacred about centralized information and patients’ rights to privacy.

Like many hospitals, this one was so bent on doing things the old way that it was heading toward bankruptcy.

My second client, a paper company mired in long-standing traditions, had taken a bold step by acquiring a dozen independent packaging companies.

The companies served many diverse industries, from media to health care, and were based in many far-flung nations, including Brazil, the United States, Russia, and Europe.

Senior managers wanted to seize the opportunity to help their clients use new packaging designs to grab customers’ attention, but they used a painstakingly deliberate engineering approach to making decisions.

The company had been through a slew of management consultants, from McKinsey to the Boston Consulting Group to Deloitte & Touche, and even management guru Ram Charan, a University of Michigan professor.

I was working with the head of the packaging group to create a design center for customers, identifying potential partners in China and India.

But after three critical years, executives were no closer to uniting their various acquisitions to provide designs for clients than when they had begun.

My third client was a cosmetic company with a household name that had too many ideas and way too little discipline.

At the same time, it was uniquely positioned to touch customers around the world, but, like many consumer-goods companies, it was being slowly asphyxiated by the complexity of its offerings.

The sales reps were so overwhelmed that they had become more like clerks processing orders than salespeople proactively describing a product.

Manufacturing facilities produced one item, then the next, and the next, unable to capture economies of scale and often discarding unused inventory.

This company was an ace at customizing orders and delivering them quickly to all reaches of the globe, yet it was missing great opportunities.

And it wasn’t just my clients that were being overwhelmed.

Something has gone wrong with business in the twenty-first century.

Consider this: Since 2000, the management at 18 different public companies—18 companies!—has each destroyed more than $50 billion in shareholder value.

That’s more than Enron did, 18 times over.

Why?

Because, in most cases, the CEOs, boards of directors, and other well-paid managers held on to yesterday—to doing business the way they always had—and didn’t know how to free their organizations to embrace tomorrow.

Management in the twenty-first century faces fundamental changes in the size and scope of opportunities.

Businesses have historically defined “opportunity” as a chance to capture market share and rake in higher profits through greater productivity, a new and improved product or service, the acquisition of a competitor, or expansion into a new territory.

But increasingly, opportunity is all about seeing, or even creating, white space—uncharted markets that can be identified only by looking hard at both the external environment and the numerous unsatisfied demands of increasingly informed customers.

What is fascinating is that often the customers aren’t even conscious of what they want until someone comes up with a product and a marketing campaign that makes people say, “I need that cell phone that shows the Comedy Channel.”

In a very real sense, truly innovative products and services create their own markets.

As I traveled to Brussels and bumped around the streets of New York in a Starbucks truck, I couldn’t get Drucker out of my mind.

All these companies—all the CEOs, all the CFOs, all the COOs, all the Chief-You-Name-Its I was dealing with—were trying to cope with this bewildering 24/7 world of outsourcing, changing demographics, sharpened competition, and new customer requirements.

They were dealing with the very challenges Drucker had anticipated for decades, before anyone truly understood what he was talking about.

As I began to reread Drucker’s books and articles, several things quickly became clear.

No one has understood the implications of social trends and transformed them into opportunities the way Drucker has (see sidebar on page 13).

No one has done a better job of helping organizations capitalize on opportunities.

Despite the vast numbers of business books, no book clearly and powerfully explains the implications of the transitions that are underway and how to effectively manage in this new world.

Something told me that this man, who had been the first to emphasize the human element of management, had some of the answers. Jump

Drucker Ideas

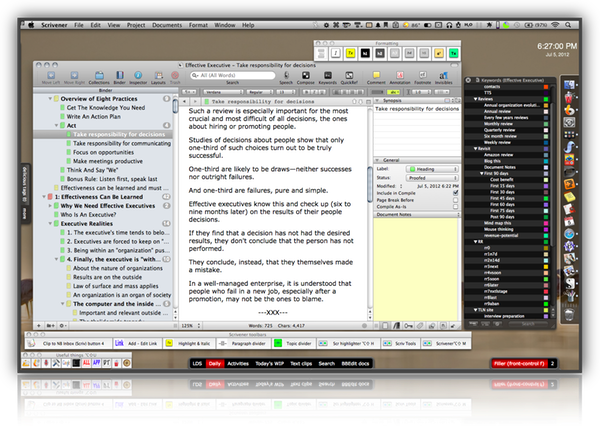

As I began to write about Peter’s ideas and share my own perspectives on them, he opened up.

I would pick one topic from my list of Drucker ideas and discuss with him how it applied to the challenges of this century.

He generally liked me to send him my questions in advance of my visit.

I would write down his responses and study them, reread something he wrote, call a client or two, and test the thinking.

For example, when we were discussing the knowledge worker, Peter said, “Today the corporation needs them more than they need the corporation.

That balance has shifted.”

I called my friend Alan Kantrow, head of the knowledge effort at Monitor, the Boston-based consulting firm.

Without missing a beat, Alan said, “We are constantly asking ourselves—what are we providing to the knowledge worker to keep him or her here, rather than go off and be an independent contractor.

We believe it is the opportunities they get and the people they have a chance to work with that keeps them here.

It is not the money.”

I then called David Thurm, head of operations at the New York Times.

In this era of job-hopping executives, David is as much of a company lifer as I know.

I asked him why he worked for the Times, rather than as an independent contractor.

He replied, “I’m proud to be associated with such a great institution.”

Drucker had told me that there is no such thing as unquestioning loyalty: An organization has to earn the loyalty of its employees every day.

David agreed and said that the Times was still earning it.

I called three other high-level executives and asked them what keeps them at their corporations.

They said they stayed on because of job security.

I guess asking this Druckerian question prodded them to think.

Since then, two have left their corporations.

While I continued consulting with companies large and small, I kept on thinking about how management could navigate this difficult new landscape and what lessons from Drucker’s 70 years of observations could help them.

I questioned executives whom I admired, added my own ideas, and shared the results with Peter as we discussed the book.

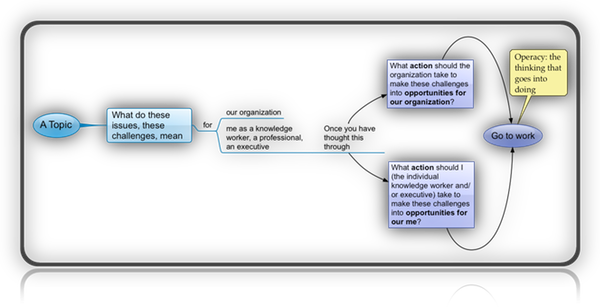

On a warm August day in 2004, during an intense conversation about what makes a good leader, Peter looked at me and said, “The most important thing anybody in a leadership position can do is ask what needs to be done. See here and here

And make sure that what needs to be done is understood.”

At the time, the newspapers were full of headlines about once-thriving businesses that were faltering badly and about scandals at Tyco, Enron, Adelphi, and WorldCom.

He continued, “You ask me why do so many people in leadership fail.

There are two reasons.

One is that they go by what they want, rather than what needs to be done.

And the second is the enormous amount of time and effort to make oneself understood—to communicate.”

I asked how leaders can be certain they know what needs to be done.

He emphasized two things: asking and listening.

Drucker was known for his Socratic style—asking questions and asking the right ones.

I once asked Dan Lufkin, a founder of Donaldson, Lufkin, & Jenrette, to describe working with Drucker back when the firm was starting in the 1960s.

First, he said, Drucker made sure everyone was focused on the questions that needed to be asked.

“I can’t tell you how important he was to the development of the firm.

He forced three young and ambitious guys doing well to step back and think, and on occasion make decisions.”

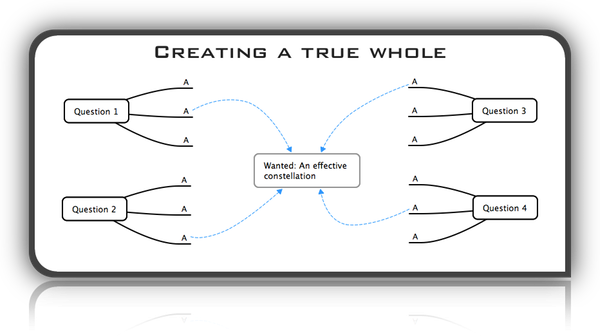

I have used Drucker’s most insightful questions to structure every chapter in this book.

As Peter often said, the right questions don’t change as often as the answers do.

As you read, think how you might answer the key questions in each chapter if you were asked them by your CEO or your customer.

The book also reflects Drucker’s passion for making organizations and management work well in the present and to create tomorrow.

The importance of and need for great management are reflected in virtually all his writing.

Peter’s passion was the direct outgrowth of having witnessed Europe’s economic free fall in 1930.

The failures and collapse that he wrote about in the 1930s were, to his mind, directly connected to poor business and government management.

He was convinced that the lack of a viable economic engine in Europe is what brought Hitler to power.

The rise of Fascism and Communism only confirmed Drucker’s view of the critical need for vibrant businesses in any society.

Without economic opportunity, he wrote in 1933, “The European masses realized for the first time that existence in this society is governed not by what is rational and sensible, but by blind, irrational, and demonic forces.”

He then went on to say that the lack of an economic engine isolates individuals and they become destructive.2

Drucker’s understanding of the fragility and interdependency of our economic systems and the enormous human cost of failure is even more relevant in our global economy.

And, as Drucker emphasized, we all must step up to the responsibility to manage our way to an optimal tomorrow.

“Human values, capabilities, and tenacity comprise the engine that keeps the world going.

In short, we are all charged with influencing and managing the changes that will define our future.”

Peter and I saw this as a book for a wide assortment of people: A CEO leading an organization, a recent recipient of an MBA or a graduate of an executive education program who wants to think about the challenges and possible solutions that academics don’t dwell on, a mid-level manager worried about declining sales, a vice president who is dealing with dilemmas of outsourcing, a CFO who is keeping a wary eye on competition from a company in another country, probably another continent.

These people have some common traits: They want the best for their businesses.

They are leery of short-term profit making at the expense of long-term growth.

And they want their careers to make a mark.

Doing Business in the Lego World

The assumptions on which most businesses are being run no longer fit reality. 1

—Peter F. Drucker

WESR ::: The theory of the business ::: Management’s new paradigms

As I crisscrossed the country over the past couple of years, interviewing Peter Drucker and working with clients, something struck me.

The staid world of business—the world I’d studied, the world I felt I’d mastered during 20 years at McKinsey & Co. and as head of my own consulting firm—had been turned upside down by a silent revolution.

In this chapter, I describe that revolution, tell you how Peter helped me understand this radical transformation, and explain what it means for you right now.

The Silent Revolution

Change came gradually, predictably, to businesses in the period following World War II through the early 1990s.

But then, boom! A silent revolution took place on five fronts:

1. Information flew.

2. The geographic reach of companies and customers exploded.

3. The most basic demographic assumptions were upended.

4. Customers stepped up and took control of companies.

5. Walls defining the inside and outside of a company fell.

Developments on these five fronts played off one another, further accelerating the revolution.

First, information flew.

Since the expansion of the Internet, information travels instantaneously, without regard for distance, and its widespread availability is unprecedented.

In the globally integrated economy, management must make decisions at all hours of the day and night.

Purchasing managers in Plano and distributors in Dubuque can now distinguish between good suppliers and bad ones instantaneously.

The greater velocity of information has accelerated the pace of everything in business.

Success is measured not by the quarter or the month, but by the minute or second.

Every industry, from manufacturing to movies, has had to adjust to this fast-forward world.

As Lynda Obst, a producer at Paramount, recently noted, “We used to have a weekend to get our money out of a movie like Stealth or Doom.

Now we get one night, tops.” 2

For decades, information was power.

But today, with the unprecedented availability of instant information to anyone with a laptop, true power comes from screening, interpreting, and translating vast quantities of information into action.

Second, the geographic reach of companies and customers exploded.

Remember that cartoon of the kid scraping a hole in the ground and saying, “Hi, Mom, I’m digging to China”?

Today that same 11-year-old gets on his Mac and connects to a peer in Guangzhou for a game of war, and his 13-year-old sister goes to sweetandpowerful.com to buy a fleece pullover made in Sri Lanka.

Companies and their customers now have an astounding geographical reach.

Even mom-and-pop firms can scour the world for resources.

And in this global marketplace, brands are created and gain widespread recognition in weeks or months rather than years, cutting down the advantage of the big-brand players who used to be the select members of an exclusive club.

Companies and their customers now have an astounding geographical reach.

Third, basic demographic assumptions were upended.

Populations in the developed world have been jolted by an aging group of workers and a declining birth rate.

The migration from industrial to knowledge workers and the increasing success of women in the workforce have changed customers’ needs and forever changed the relationships of corporations with both customers and employees.

Until quite recently, only customers in affluent countries reached the apex of Maslow’s pyramid of self-actualization, which starts with the basics of food and shelter.

Now, millions more people in all social strata have been freed from worrying about the basics; they seek service and fulfillment.

With longer life spans, later retirements, and a record number of women in the workplace, convenience matters more than ever.

I noticed recently that my supermarket was touting pre-made peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for parents who don’t have an extra 60 seconds to slather two spreads on bread.

With changes in how customers are distributing their income, companies are offering more useful information and more service.

The three fastest-growing consumer purchases today are not traditional consumer goods; they are activities (such as sporting events and health club memberships), health care, and education.

Health care and education make up almost a third of America’s gross national product (GNP).

To managers, the biggest effect of these demographic changes is that societies, markets, and workplaces are driven by new populations with new demands.

Once-dependable workers over age 50 do not necessarily keep on toiling as full-time, 9-to-5 employees.

Instead, many dive into the labor force as temporaries, part-timers, consultants on special assignment, or knowledge workers.

Some of these older workers will be pushed into free agent status because of layoffs and buyouts.

Fourth, customers stepped up and took control.

Never before have customers been so clearly in the driver’s seat.

They are engaged with companies in ways that would have astounded Henry Ford or Thomas Watson.

Customers are no longer simply passive recipients of goods and services; they are active participants from the product inception, whether as groups evaluating the product or as individuals working with software programs and design engineers to custom-build everything from Levi’s jeans to light fixtures.

Consumers can access virtual shelves for almost any product, and they want customized products delivered with the click of a mouse.

Customers create their own weblogs with their own online content.

Hachette closed its Elle Girl Teen magazine while its competitor, Condé Nast, is launching a Web site with all its content created by teen readers rather than by Condé Nast staffers.

We read each other’s blogs and socialize at virtual meeting places such as MySpace.com and the online dating site Match.com.

Shopping for a mate has become almost as easy as shopping for a book on Amazon.com (“Add this man or woman to My Cart!”).

Savvy customers have become part of the process that used to exclude and dismiss them with condescending remarks like, “You’ll have that dining room table delivered in eight weeks.

And, no, we cannot make it three inches taller just because you have a relative in a wheelchair—you’ll have to find a carpenter to do that.”

Today you design it with one of several manufacturers such as Thomas Moser—often online—exactly the way you want it.

Finally, defining walls fell.

These days, a company draws on capabilities outside its own walls in ways that would have been unheard of just a few years ago.

To test ideas, companies now use expertise drawn from completely different industries and form alliances with other companies with overlapping missions.

Since Home Depot recognized that its strength was internal to its stores, it has passed all its logistics issues off to UPS; now UPS manages everything at Home Depot connected with shipping.

This partnership allows the two companies collectively to serve Home Depot customers more efficiently.

Sometimes companies even team up with direct competitors.

Last year, two global rivals, China National Petroleum Corp. and India’s Oil & Natural Gas Corp., teamed up to buy a Syrian oil field, and this year they jointly bid for another one in Colombia.

Walls have fallen to bring the best people and divisions within companies together rapidly and to enable organizations to adapt without huge write-offs.

Whereas independence was once key to speed and a barrier to the entry of competitors, it has come to signify isolation.

And isolation is corporate death.

The impact of this silent revolution hit me one day in 2005.

Although I had studied the company carefully twice before, I was making my first visit to Procter & Gamble (P&G) in Cincinnati as a writer.

Everyone welcomed me, from sales reps to the chairman, president, and CEO, A.G. Lafley.

They wanted my thoughts, and they were eager to give me every bit of information I requested.

What a vast change this warm reception was from my two prior dealings with the firm in 1990 and again a decade later in 2000.

I wasn’t working for P&G on either occasion; I was studying it for a competitor.

Back then, the Cincinnati behemoth was so secretive that the chairman of my client company told me not to even so much as mention P&G’s name in any report.

He felt that if P&G found out I was analyzing it, there would be “repercussions.”

I dubbed it Company S for “secret”—as if any executive couldn’t figure out who was making all those soaps, detergents, and diapers I was writing about.

Now here I was in Cincinnati in 2005—feeling a certain amount of dread mixed with excitement—interviewing Lafley over a lunch of chicken and green beans in his office.

At the conclusion of our meeting, he told me to call with any questions.

And it wasn’t just Lafley who was forthcoming.

Rather than a hermetically sealed conglomerate, I found a company so open that it invited me, an outsider, to visit one of its product testing centers.

The company is intent on tapping outside sources and retirees for research and development (R&D) and is even testing a program with DuPont to link the two firms’ technology centers.

P&G had changed its attitude so radically that it was letting employees write articles about how they were managing.

Drucker’s influence was apparent.

He had been working with P&G since about 1990, and he had constantly pushed executives to see beyond the borders of Ohio.

And they had listened.

On my way home, I reflected on my day.

What impressed me was not just that P&G was more open; what was really striking was that it was rethinking the way it did everything.

I had seen the same ability to rethink the present and embrace the future at GE’s corporate headquarters in Connecticut, and then across the country at a completely different place—the Myelin Repair Foundation, a little-known start-up foundation in northern California.

Embracing The Future

My GE experience began as I prepared to interview its former chairman, Jack Welch, a long-time Drucker client.

Before seeing this legendary executive, I wanted to know what GE insiders thought and what tips they could offer for drawing Welch out.

I called Dave Stevenson, a friend who used to run GE’s major appliances marketing group.

He told me that he had created his own company, doing research on major consumer expenditures.

Seven companies, including GE, were buying his research and market planning.

That was unusual for GE, which used to distrust outside researchers.

But Dave said that Welch had forced the major appliance group to ask not only what others could do better, but what activities should be spun off and which department heads could work independently.

When Dave had volunteered to take marketing outside, the bosses surprised him by agreeing to it.

Dave gave me his tip: Listen to Jack Welch and don’t be offended by his rough style.

Another thing: Jack likes specific questions that demand specific answers.

When I called Welch at the appointed time, I grabbed his attention by asking what he was doing for his birthday.

He asked me how I knew, and I told him it was the same as Peter Drucker’s—a bit of trivia that surprised him.

My second question was how Peter had influenced him.

He said that Peter had made him conscious of GE’s ability to work with another organization that was excited about something that GE found boring.

“If it’s not your front room,” Peter had asked Welch, “can you make it someone else’s front room?”

Peter had expressions that everyone seemed to remember.

His point was that if you don’t have passion for a particular activity, then find an ally who has expertise and passion for that activity and can do it better.

Harness GE’s clout and the ally’s passion and move forward.

“GE recognized that they were never going to be the best in the world at programming and found a company that was passionate about it in India 20 years before anyone else,” Welch told me.

This wasn’t what the press calls outsourcing.

Outsourcing is meant to save money or make things easier for the manufacturer.

Instead, GE wanted to put the best teams together, even if some members were external and including them added to logistical demands.

It sought partnerships that would deliver the best value to the customer.

Jack termed this shift “boundarylessness” and indicated that it is a continual challenge for most companies.

Over the years GE executives continued to ask themselves that question and go outside its walls more and more.

This effort began in earnest with Peter exhorting Welch to focus on strengths and find somebody else to do the rest.

Big, profit-hungry companies aren’t the only ones breaking boundaries.

After talking to Welch, I visited the Myelin Repair Foundation, an innovative group in northern California that is trying to find a cure for multiple sclerosis (MS).

(This organization is discussed in detail in Chapter 4.)

Its approach challenges two long-standing practices that create barriers in research.

First, the foundation is connecting separate, competing research groups that used to share findings only after their papers were published.

A group of five leading neuroscientists from different universities are piloting a new, collaborative approach to medical research with a shared research plan right from the start.

Second, the foundation is collaborating with patients at every step—something even the best researchers don’t do.

Their meetings include not just researchers and fund-raisers but also patients, the people most affected by MS.

The patients’ presence creates a new sense of focus and urgency in the researchers.

This isn’t an academic exercise that will culminate in articles for specialized journals.

This is about life and death and about finding a breakthrough in a few years, not in a future someone’s lifetime.

The scientists are looking for take-home solutions to the deterioration of myelin, the protective insulation surrounding nerve fibers of the central nervous system, which is destroyed by MS.

This relatively small foundation is pioneering the twenty-first-century way of doing business.

Industrial mainstays like P&G and GE and newcomers like the Myelin Repair Foundation are reshaping where and how companies work with customers, other stakeholders, and even potential rivals.

These innovators are accelerating the pace at which companies connect, disconnect, and reconnect.

P&G and GE recognize that the financial market values soft assets, such as customer relationships, international access and agility, and intellectual capital, and that’s where they put their investments.

We’ll learn from their successes—and some of their mistakes—throughout this book.

To paraphrase Drucker, embracing the new requires abandoning the past.

In our conversations, he often said that we are at a moment of transition where businesses and organizations will be redefined.

If they don’t, they’ll go the way of pterodactyls.

The Primacy Of Knowledge

I was eager to test my observations about the silent revolution with Peter Drucker the visionary who had an astounding track record in predicting and shaping the future.

The companies I advised were reeling from the changes around them, and I knew his counsel would make my advice better.

It was a lucky coincidence that several of the companies I worked with had consulted with him decades earlier.

When I drove to Drucker’s house in a middle-class enclave of Claremont, California, in February 2005, a lone Toyota sedan was parked in the driveway.

I remembered my first visit the previous summer when we began to talk about the possibility of my writing a book.

On that day, I drove by the house three times, checking the address.

It was a nice house, but not ostentatious—an average ranch house in an average neighborhood.

It did have distinctive landscaping.

The lawn resembled one of those British creations where someone manages to cram in twice as many plants as you’d think possible and make it look wonderful nonetheless.

This time, with the book under way, I rang the bell and heard Peter’s usual, “Just a moment!”

Then I heard a thumping noise through the house.

Peter opened the door and commented, “I’m not as fast as I used to be.”

The thought flashed through my mind, maybe not physically.

He continued, “Pleased to see you.”

He grabbed my hands and said, “Well, come in.”

We walked past Doris’s office and a shelf stacked with mail.

We walked through the living room, which was always immaculate.

The Financial Times was spread on a long table.

We sat down in the den, next to a round coffee table, with me on his right, by his better ear.

Peter enjoyed small talk, but today we plunged right into a business discussion.

I wondered if he had noticed the phenomenon of the outside world becoming part of companies.

I began by asking his thoughts about the most important challenge for managers today.

I used the classic B-school question: What should be keeping managers up at night?

He laughed and said, “I don’t know.”

By now, I understood him well enough to realize that he did know.

This was his way of prodding a questioner to dig for the answer.

Then he’d go into his “I’ll-tell-you-something-else; we’ll-get-back-to-that-question-shortly” routine.

We did get back to it, and this chapter does too, in a moment.

Peter often talked in circles—beginning with something that might appear totally unrelated and ending with an insight into a question.

Somehow it connected to his initial observation.

In this case he didn’t start by discussing managers, or even science.

He talked about World War II.

It was, he said, the first war won on industrial power, not military depth.

It was the first time in which industry was not an auxiliary but the main fighting force itself.

In fact, in the first six months, the United States manufactured more aircraft, tanks, and artillery than Hitler and his advisers thought the Americans could make in five years.

They did it by applying the discipline of management from operations research and quality control to rapidly convert factories from making cars to producing tanks.

Peter then mentioned my friends from the Sloan School and the role they had played.

That led him to a soliloquy about peace.

He said that any peace following such a war must be an industrial peace—a peace in which industry is not just on the periphery but at the center.

He was on a roll, tracing the transition from a mercantile economy to an industrial economy and the concomitant tension between policy and reality.

Peter observed that we are now in another critical moment: the transition from the industrial to the knowledge-based economy …

We should expect radical changes in society as well as in business.

“We haven’t seen all those changes yet,” he added.

Even the very products we buy will change drastically.

I asked how the Americans won the Gulf War in 1991.

He didn’t take his usual moment to collect his thoughts.

“Technology,” he shot back.

When I asked how the war on terrorism will be won, he took a moment and said, “Knowledge.”

He then explained the difference to me: “Technology is the application of yesterday’s knowledge.

The war on terrorism will be won based on our ability to apply knowledge to knowledge—or someone else’s ability.”

He meant the ability to integrate the pieces and add to what we know individually.

And that brought us to management, or what he called “knowledge-based management.”

He spent the better part of the next two hours defining and pulling this idea apart: the importance of accessing, interpreting, connecting, and translating knowledge.

He spoke about how critical it is to find and manage knowledge in new places like pharmaceutical companies as they move beyond chemistry to nanotechnology and software.

How would this search and application

be choreographed?

Knowledge-based management is also critical to old multinationals like GE as they begin to build infrastructure for the developing countries, with the caveat that they first need to fully understand those countries.

See Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown

Essentially, GE has to access information about the developing world and its infrastructure, interpret this information, and connect it with the rest of GE.

The educated person

Drucker commented that information will be infinite; the only limiting factor will be our ability to process and interpret that information.

That is what he meant when he emphasized the importance of the productivity of the knowledge worker.

Peter had a way of looking at something and teasing out both the positive and the negative.

“On the one hand, it’s important to specialize,” he said.

“On the other hand, it’s dangerous to overspecialize and be isolated.”

The ability to access specializations while cutting across them—that’s what I’d seen at the headquarters of the Myelin Repair Foundation only a few hundred miles away.

Finally, Peter was answering my questions — finding a way to specialize enough, but not too much, and without isolation.

“That,” he said, “is what should keep managers up at night.”

Doris appeared.

All too quickly my morning session with Peter had ended.

That afternoon, when I went back, our topic was Thomas Friedman’s best-seller The World Is Flat.

Friedman argues persuasively that it doesn’t matter where work gets done—it makes no difference whether a computer company produces a part in India or Indiana.

Everywhere I went, executives seemed to agree: The world is flat.

I asked Peter if he thought the world was flat.

“From whose perspective?” he asked.

“Yours,” I said.

“I have trouble walking around my living room,” he joked.

“It doesn’t seem flat to me.”

His mind was so spry that sometimes I forgot he was 95 years old.

“All right,” I said, “then from the manager’s perspective.”

He paused and said, “Their landscape is flat only if there is an opportunity from it being flat.

But if there is an opportunity, it will not be flat for long."

The Lego World

After several more discussions with Peter, I came to understand what he was telling me.

The management world is flat only if you take an industrial perspective.

If you just want the lowest cost, the capabilities exist virtually every place in the world to get the lowest cost.

But if cost is not your only concern and you recognize that the industrial world has given way to an information and knowledge-driven world, you will see that the world is not flat and that Indiana and India are not interchangeable.

Indeed, the ability to put together and connect the pieces in different ways and with the customer all the time defines an enterprise’s performance.

Many more than two dimensions of place and time matter all the time.

Even country geography is not flat.

Silicon Valley is different from Silicon Alley which is different from Wall Street.

In the twenty-first century, businesses exist in a Lego world.

Companies are built out of Legos: People Legos, Product Legos, Idea Legos, and Real Estate Legos.

And these aren’t just ordinary Legos; they pass through walls and geographic boundaries, and they are transparent.

Everything is visible to everyone all the time.

Designing and connecting the pieces is at least as important as providing them.

It’s crucial to remember that these aren’t simply pieces of plastic or metal—they are not just factories or warehouses.

They are also humans who program computers, train newcomers, and think about innovation as they prowl malls, libraries, and parks, coming up with new products.

These pieces are constantly being put together, pulled apart, and reassembled.

My company’s Legos—manufacturing, distribution, skills, and services—cannot be unique unto themselves; they have to connect with your company’s Legos.

I can build my company, but in a year or two, my CEO and I might have to tear down and rebuild part of it in a totally different configuration, perhaps with fewer American People Legos and more of your company’s People Legos in Sweden or South Africa.

Leading visionaries in business are expressing the same notion.

Ray Ozzie, Microsoft’s chief software architect, recently explained: “What’s more important than any one individual Lego is that you know how to build with all the Legos.

With everything out there, all those programs and applications and accessories, what’s important is the ability to find a way to connect fragmented software pieces rather than simply finding the next piece of software.” 6

That’s the idea that Peter embraced, but it was larger than software and components.

He thought in terms of people, with a tremendous sense of humanity and compassion for the individual.

That’s the beauty of it.

We are not talking about commodities.

We are talking about individuals and their ability to create.

Connections ↓

A society of organizations

Management Challenges for the 21st Century | The Change Leader

Making the Future

Serious Creativity

The bright idea

Sur/petition

Creativity Workout

Only connect

As these Legos connect and interconnect in ways we could never have imagined a decade ago, when the Internet was in its infancy, we find a powerful, human structure.

In an organization, we can connect individuals’ strengths, minimizing their weaknesses.

And across organizational boundaries, we can connect the strengths of each corporation and provide the customer with far greater value than can any single enterprise.

Dell is a classic example of a Lego manufacturer.

It has configured its offering so that customers can custom-build computers to meet their individual needs.

Michael Dell claims that the firm’s important capabilities are the management and integration of information and the ability to quickly build a computer to a customer’s specifications.

Dell’s Product Legos include anything from processor and memory capacity to screen size.

Its internal network includes vendors, shipping locations, and the location of the customer service center (depending on the time of day, customers can be helped by someone in South Africa, India, or Texas).

Connecting pieces include Dell’s systems, user interface, assembly centers, and customer support service.

Although Dell recognizes customer service as its weakest link, Dell can deliver a customer-tailored product to anyplace in the world at an incredible speed, largely because of the interchangeability of its components, which is at the heart of Dell’s “Lego-like” operations.

Dell’s challenge will be to disconnect and reconnect in a new way as the PC moves from a work-tool to the entertainment and communication center.

Amazon exemplifies the Lego approach in the retailing arena; it connects with other vendors who have expertise in making everything from textbooks to toys.