Opportunities

What are the opportunities time and history have (will) put within your grasp? — Peter Drucker

Growth comes from exploiting opportunity.

Opportunities are what a specific business makes happen — and this means fitting a company’s specific excellence to the changes in marketplace, population, economy, society, technology, and values — The Changing World of the Executive (good growth/bad growth)

The unexpected failure: Yet if something fails despite being carefully planned, carefully designed, and conscientiously executed, that failure often bespeaks underlying change and, with it, opportunity — Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Organization Efforts — Problems or Opportunities

The Return on Luck

Danger of too much planning

Focus on opportunities

Good executives focus on opportunities rather than problems.

Problems have to be taken care of, of course; they must not be swept under the rug.

But problem solving, however necessary, does not produce results.

It prevents damage.

Exploiting opportunities produces results.

Above all, effective executives treat change as an opportunity rather than a threat.

They systematically look at changes, inside and outside the corporation, and ask, “How can we exploit this change as an opportunity for our enterprise?”

Specifically, executives scan these seven situations for opportunities:

⁃ an unexpected success or failure in their own enterprise, in a competing enterprise, or in the industry;

⁃ a gap between what is and what could be in a market, process, product, or service (for example, in the nineteenth century, the paper industry concentrated on the 10% of each tree that became wood pulp and totally neglected the possibilities in the remaining 90%, which became waste);

⁃ innovation in a process, product, or service, whether inside or outside the enterprise or its industry;

⁃ changes in industry structure and market structure;

⁃ demographics;

⁃ changes in mind-set, values, perception, mood, or meaning; and

⁃ new knowledge or a new technology.

Effective executives also make sure that problems do not overwhelm opportunities.

In most companies, the first page of the monthly management report lists key problems.

It’s far wiser to list opportunities on the first page and leave problems for the second page.

Unless there is a true catastrophe, problems are not discussed in management meetings until opportunities have been analyzed and properly dealt with.

Staffing is another important aspect of being opportunity focused.

Effective executives put their best people on opportunities rather than on problems.

One way to staff for opportunities is to ask each member of the management group to prepare two lists every six months—a list of opportunities for the entire enterprise and a list of the best-performing people throughout the enterprise.

These are discussed, then melded into two master lists, and the best people are matched with the best opportunities.

In Japan, by the way, this matchup is considered a major HR task in a big corporation or government department; that practice is one of the key strengths of Japanese business.

The Effective Executive

Strengths Are the True Opportunities

The effective executive makes strength productive.

He knows that one cannot build on weakness.

To achieve results, one has to use all the available strengths—the strengths of associates, the strengths of the superior, and one's own strengths.

These strengths are the true opportunities.

To make strength productive is the unique purpose of organization.

It cannot, of course, overcome the weaknesses with which each of us is abundantly endowed.

But it can make them irrelevant.

Its task is to use the strength of each man as a building block for joint performance.

The Effective Executive

Focusing managerial vision on opportunity

First among these, and the simplest, is focusing managerial vision on opportunity.

People see what is presented to them; what is not presented tends to be overlooked.

And what is presented to most managers are “problems”—especially in the areas where performance falls below expectations—which means that managers tend not to see the opportunities.

They are simply not being presented with them.

Management, even in small companies, usually get a report on operating performance once a month.

The first page of this report always lists the areas in which performance has fallen below budget, in which there is a ‘shortfall,” in which there is a “problem.”

At the monthly management meeting, everyone then goes to work on the so-called problems.

By the time the meeting adjourns for lunch, the whole morning has been taken up with the discussion of those problems.

Of course, problems have to be paid attention to, taken seriously, and tackled.

But if they are the only thing that is being discussed, opportunities will die of neglect.

In businesses that want to create receptivity to entrepreneurship, special care is therefore taken that the opportunities are also attended to (cf. Chapter 3 on the unexpected success).

In these companies, the operating report has two “first pages”: the traditional one lists the problems; the other one lists all the areas in which performance is better than expected, budgeted, or planned for.

For, as was stressed earlier, the unexpected success in one’s own business is an important symptom of innovative opportunity.

See the change leader in Management Challenges for the 21st Century

If it is not seen as such, the business is altogether unlikely to be entrepreneurial.

In fact the business and its managers, in focusing on the “problems,” are likely to brush aside the unexpected success as an intrusion on their time and attention.

They will say, “Why should we do anything about it?

It’s going well without our messing around with it.”

But this only creates an opening for the competitor who is a little more alert and a little less arrogant.

Typically, in companies that are managed for entrepreneurship, there are therefore two meetings on operating results: one to focus on the problems and one to focus on the opportunities.

One medium-sized supplier of health-care products to physicians and hospitals, a company that has gained leadership in a number of new and promising fields, holds an “operations meeting” the second and the last Monday of each month.

The first meeting is devoted to problems—to all the things which, in the last month, have done less well than expected or are still doing less well than expected six months later.

This meeting does not differ one whit from any other operating meeting.

But the second meeting—the one on the last Monday—discusses the areas where the company is doing better than expected: the sales of a given product that have grown faster than projected, or the orders for a new product that are coming in from markets for which it was not designed.

The top management of the company (which has grown ten-fold in twenty years) believes that its success is primarily the result of building this opportunity focus into its monthly management meetings.

“The opportunities we spot in there,” the chief executive officer has said many times, “are not nearly as important as the entrepreneurial attitude which the habit of looking for opportunities creates throughout the entire management group.”

Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Innovation Means Looking on Change As an Opportunity

Systematic innovation requires a willingness to look on change as an opportunity.

Innovations do not create change.

That is very rare.

They may if successful make an enormous difference, but most of the innovations that aim at changing society, or market, or customer, fail.

Innovations that succeed do so by exploiting change, not attempting to force it.

In Innovation and Entrepreneurship (1985) I wrote that “systematic innovation … consists in the purposeful and organized search for changes, and in the systematic analysis of the opportunities such changes might offer for economic or social innovation.”

I went on to identify seven sources to look out for as signs and sources of a chance to innovate.

Four of these sources are within the enterprise (business or otherwise) or the industry in which they operate.

They are basically symptoms of change.

They are: the unexpected success or failure; the incongruity (the discrepancy between reality as it is and reality as it is assumed to be); innovation based on process need; and changes in industry or market structure that take people unawares.

The other three sources involve changes outside the industry or enterprise, namely, demographics; changing tastes, perceptions, and meanings; and new knowledge, both scientific and nonscientific.

The most useful of the seven “windows” of innovation (which is why I list it first) is always the unexpected, especially the unexpected success.

It is the least risky and the least arduous.

Yet it is almost totally neglected.

What is even worse, managers often actively reject it.

Consider for a moment that prime product of modern accounting: the monthly or weekly report.

This was a tremendous eye-opener.

Nobody had ever had systematic figures before.

Most people see the first page that shows them they are over budget, but how many receive the other “first” page that shows where they are ahead of budget?

They should order their accountants to produce it immediately.

Without this information an organization becomes fixated on its problems.

However, it is usually the case that the first indication of an opportunity is where a company is faring better than expected.

Most of the figures and variations turn out to be not significant, of course, and managers can explain them immediately.

But one out of every 20 might mean something.

It might be pointing to something we did not know.

A leading hospital supplier launched a new line of instruments for clinical tests.

The new products did quite well.

Then suddenly orders started appearing from a quite different spectrum of customers: university, industry, and government laboratories.

No one noticed that the company had tripped over a new and better market.

It did not even send a sales person to visit the new customers.

The result: a competitor has not only recognized and captured the industrial laboratory market; exploiting the scale of the new segment, it has seized the hospital market, too.

This is a very typical story.

The first firm had failed to understand the significance of an unexpected success.

It has now been bought out by a pharmaceutical company.

Of the other sources of innovation, scientific and technical research is listed last because, although undeniably important, it is also the most difficult, has the longest lead time, and is the most risky.

We know quite a bit about how to manage research.

But, as with other change opportunities, the important part is systematically to look out of the windows and ask, is this an opportunity for the company?

And if so, what kind of an opportunity?

Most changes for most companies are not.

Changes in population structure are very important for some businesses and totally unimportant for others.

For a steel mill, except in so far as it affects the labor supply, there is almost no interest in demographics.

On the other hand, changes in environmental awareness are of tremendous importance to a steel mill.

Managing for the Future

13 JUL — Unexpected Success

It takes an effort to perceive unexpected success as one’s own best opportunity.

It is precisely because the unexpected jolts us out of our preconceived notions, our assumptions, our certainties, that it is such a fertile source of innovation.

In no other area are innovative opportunities less risky and their pursuit less arduous.

Yet the unexpected success is almost totally neglected; worse, managements tend actively to reject it.

One reason why it is difficult for management to accept unexpected success is that all of us tend to believe that anything that has lasted a fair amount of time must be “normal” and go on “forever.”

This explains why one of the major U.S. steel companies, around 1970, rejected the “mini-mill.”

Management knew that its steelworks were rapidly becoming obsolete and would need billions of dollars of investment to be modernized.

A new, smaller “mini-mill” was the solution.

Almost by accident, such a “mini-mill” was acquired.

It soon began to grow rapidly and to generate cash and profits.

Some of the younger people within the steel company proposed that available investment funds be used to acquire additional “mini-mills” and to build new ones.

Top management indignantly vetoed the proposal.

“The integrated steelmaking process is the only right one,” top management argued.

“Everything else is cheating—a fad, unhealthy, and unlikely to endure.”

Needless to say, thirty years later the only parts of the steel industry in America that were still healthy, growing, and reasonably prosperous were “mini-mills.”

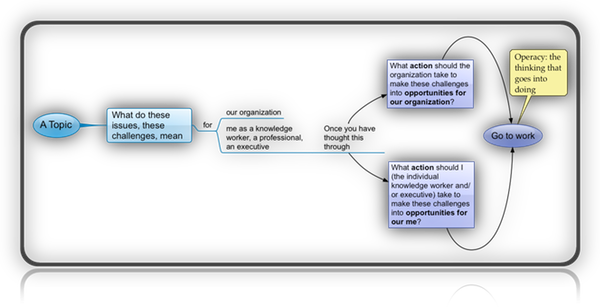

Larger view of challenge thinking image below

Note the fog and reflection ↓

Write An Action Plan

Executives are doers; they execute.

Knowledge is useless to executives until it has been translated into deeds.

But before springing into action, the executive needs to plan his course.

He needs to think about desired results, probable restraints, future revisions, check-in points, and implications for how he'll spend his time.

First, the executive defines desired results by asking: "What contributions should the enterprise expect from me over the next 18 months to two years?

What results will I commit to?

With what deadlines?"

Then he considers the restraints on action: "Is this course of action ethical?

Is it acceptable within the organization?

Is it legal?

Is it compatible with the mission, values, and policies of the organization?"

Affirmative answers don't guarantee that the action will be effective.

But violating these restraints is certain to make it both wrong and ineffectual.

The action plan is a statement of intentions rather than a commitment.

It must not become a straitjacket.

It should be revised often, because every success creates new opportunities.

So does every failure.

The same is true for changes in the business environment, in the market, and especially in people within the enterprise—all these changes demand that the plan be revised.

A written plan should anticipate the need for flexibility.

In addition, the action plan needs to create a system for checking the results against the expectations.

Effective executives usually build two such checks into their action plans.

The first check comes halfway through the plan's time period; for example, at nine months.

The second occurs at the end, before the next action plan is drawn up.

Finally, the action plan has to become the basis for the executive's time management.

Time is an executive's scarcest and most precious resource.

And organizations—whether government agencies, businesses, or nonprofits—are inherently time wasters.

The action plan will prove useless unless it's allowed to determine how the executive spends his or her time.

Napoleon allegedly said that no successful battle ever followed its plan.

Yet Napoleon also planned every one of his battles, far more meticulously than any earlier general had done.

Without an action plan, the executive becomes a prisoner of events.

And without check-ins to reexamine the plan as events unfold, the executive has no way of knowing which events really matter and which are only noise.

The Effective Executive

An incomplete list — but good enough for the next 50 years

What executives should remember (Theory of the Business) What executives should remember (Theory of the Business)

Managing in the Next Society Managing in the Next Society

Management Revised Edition Management Revised Edition

Management Challenges for the 21st Century Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Managing for Results AND/OR From Analysis to Perception — The New Worldview Managing for Results AND/OR From Analysis to Perception — The New Worldview

Innovation Innovation

Innovation and entrepreneurship chapters 3 (the unexpected) through 9. Innovation and entrepreneurship chapters 3 (the unexpected) through 9.

Entrepreneurship and Innovation Entrepreneurship and Innovation

The Definitive Drucker The Definitive Drucker

Opportunities by Edward de Bono Opportunities by Edward de Bono

“The reasons that many opportunities pass us by is a perceptual one — we do not recognise an opportunity for what it is. An opportunity exists only when we see it.”

Serious creativity Serious creativity

Sur/petition Sur/petition

Remember to calendarize this?

List of topics in this Folder

|

![]()