Peter Drucker: The Über Mentor

Top of the food chain ↑ ↓

Jump to article start?

#pdw larger ↑ ::: Books by Peter Drucker ::: Rick Warren + Drucker

Hong Kong more recent

“I am not a ‘theoretician’;

through my consulting practice

I am in daily touch with

the concrete opportunities and problems

of a fairly large number of institutions,

foremost among them businesses

but also hospitals,

government agencies

and public-service institutions such as museums and universities.

And I am working with such institutions on several continents:

North America, including Canada and Mexico;

Latin America;

Europe;

Japan and

South East Asia.” — PFD

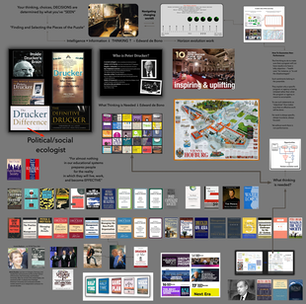

Drucker called himself a

social / political ecologist

— concerned with man’s

man-made environment —

much like the way the natural ecologist

studies the natural environment.

A Functioning Society ::: The (human) Ecological Vision ::: The End of Economic Man

That man-made environment includes everything that is not part of “natural, primitive nature.”

Three foreigners — all Americans — are thought by the Japanese be mainly responsible for the economic recovery of their country after World War II and for its emergence as a leading economic power.

Edwards Deming taught the Japanese statistical quality control and introduced the “quality circle.”

Joseph M. Juran taught them how to organize production in the factory and how to train and manage people at work.

… snip, snip …

I am the third of these American teachers.

My contribution, or so the Japanese see it, was to … continue

From: Inc. Magazine,

Sept 2002

By Elaine Appleton Grant

Source

sidebar #CAF ↓

Most mistakes in thinking ↓

Sixteen different angles

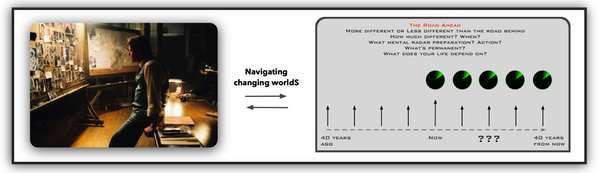

Your thinking, choices, decisions are determined

by what you’ve “SEEN”

… and the choice of attention area …

… at a point in time

“Once perception is directed in a certain direction

it cannot help but see,

and once something is seen,

it cannot be unseen”

Drucker: Political/social ecologist

main brainroad continues ↓

If you needed (wanted)

life-changing

advice (guidance)

and could make only one phone call,

who would be on the other end?

For some, the answer is Peter Drucker.

sidebar #CAF ↓

Remembering Peter Drucker — The Economist

What thinking is needed?

main brainroad continues ↓

There are personal mentors—the peer in your networking group, your old partner, your dad.

And then there is Peter F. Drucker.

Peter’s Principles

The 92-year-old author is far more than the grand master of management theory. Not a theoretician

For a fortunate, surprisingly large club, he has been the single most lucid, eloquent, and encouraging force in their lives.

Consider Peter Drucker the North Star of mentors. (He liberated people)

The rest are only streetlights.

Writing timeline

Drucker, however, would probably prefer to be likened to that functional floodlight than to anything remotely celestial.

According to his friends, the erudite scholar (not a scholar but a writer and social ecologist) is almost shockingly down-to-earth.

Drucker’s generosity of spirit and his accessibility have surprised the raft of executives who have sought his counsel over the years.

Bob Buford (Half Time), a philanthropist and author living in Dallas, tells a story about how, at Drucker’s 80th birthday party, a line of people went to the podium to talk about their relationship with him.

“All of us had the same story,” Buford says.

“We all had wanted to talk to Peter because we knew he was the wisest man alive.

# 12 'What is the definition of "wisdom"?'

A Functioning Society ::: The (human) Ecological Vision ::: The End of Economic Man

And we were all scared to death to talk to him because he’s this figure on Mount Rushmore.

So all of us plotted, planned, and found an excuse to talk to him, and all of us found him incredibly accessible, incredibly gracious as a human being, and very focused and responsive to our issues.”

What is it, exactly, that makes Peter Drucker such an effective mentor?

He himself won’t say.

“I never talk about [the people I advise], let alone about my relationship with them,” he told us.

“You have to talk to them.”

And so we did.

Here are three of their stories.

Contained in them are clues about how an expert mentor operates—and how to get the most from a mentor when you find one.

John Bachmann

In the late 1970s, when John Bachmann was a general partner at securities firm Edward Jones, he and managing partner Edward D. “Ted” Jones Jr. became Drucker devotees.

Over the course of a year they discussed each chapter of his magnum opus Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices and then began attending his speeches.

In 1980, Bachmann visited David Jones, the head of Humana, the Louisville health-care company.

Listening to Jones, Bachmann recognized the great man’s influence.

“I said to him, ‘You’ve read Drucker,’” Bachmann recalls.

“And Jones says, with a stage pause, ‘We go see him.’”

Bachmann asked Jones the secret to getting to see Drucker and subsequently spent a month crafting a half-page letter to him.

When Drucker received it, he called Bachmann and said, “I’m not taking new clients, but I’m intrigued with what you’re doing.”

Bachmann spent four more weeks writing another letter.

He wanted help in figuring out how to build the company to thrive in what he perceived would be a vastly more complicated future.

After receiving Bachmann’s second plea, Drucker said, “Come see me.”

That was the beginning of a two-decade-long relationship.

Bachmann credits Drucker with being the “set of instructions” that enabled him and Ted Jones to grow the company from a $19-million business with 750 employees to what it is today—a $2.1-billion company with 25,000 employees.

He also credits Drucker with helping them create a great place to work.

“Peter understands as well as anyone that success in an organization needn’t ever come at the sacrifice of humaneness,” he says.

“Peter has warned us (#operacy) that there are jobs that are man killers.

He’s warned us against creating positions that are destined for failure.”

What’s it like to talk to Drucker?

He draws on a rich well of knowledge and peppers his conversation with analogy, says Bachmann.

“He is in no way bound by the language and disciplines of business.

When he talks about an issue, he very well could be talking about César Franck or Franz Liszt using musical examples, then he skips to Japanese art, and then Egyptian art, and draws that together with some example of the Catholic Church and the formation of education.”

On a personal level, Bachmann says, Drucker helped him become more patient and to “have faith in people I might otherwise have been critical of.

He has an extraordinary faith in people—he’s quick to see the strength.

One of the great lessons of Peter is to build on people’s strengths so that you make their weaknesses irrelevant.”

Drucker became upset with the Edward Jones team once.

“We had been involved in an underwriting that had stubbed its toe badly, and we were very down on ourselves, feeling sorry for ourselves,” Bachmann says.

“And he gave us the strongest scolding he’d ever given us.

He said:

‘What makes you think

you’re exempt from

the normal bumps and bruises

of life?

Are you supposed to

go through life

without having anything go wrong?

The question isn’t, Do you make mistakes?

It’s, Do you learn from them?’” ( #operacy / calendarize this?)

Nan Stone

Nan Stone got to know Drucker in 1985, when, as a member of the Harvard Business Review editing staff, she was assigned to be his editor.

Although he hates being rewritten, she says, “he quite likes being edited.”

Eventually, he invited Stone to visit him at his home in Claremont, Calif., which she did on several occasions.

They developed a friendship—a relationship that in general was far less formal than the one he has with many.

Drucker impressed upon Stone his principle of recognizing and building on people’s strengths; he affirmed that she was, indeed, a good editor.

He also helped her keep her personal priorities straight as she negotiated the difficult transition to the role of HBR’s editor-in-chief.

He did that subtly, mostly by unfailingly asking her about her husband and daughter.

“Things weren’t off limits,” Stone says.

“Peter takes you as a whole person and in that sense encourages you to be a whole person.

Given that the pressures of modern life can often play in a different direction, that was important for me.”

She could have succumbed to the pressure to work all the time and thus ignore her daughter.

Instead, she made time for her daughter—and consciously tried to make the HBR editorial offices into a place where people had time for their private lives.

Stone, who today is a partner at the Bridgespan Group in Boston, tries to model her own mentoring style after Drucker’s.

“I’ve learned to listen to someone else and to ask them questions that help them clarify their strengths, what their interests are—and encourage them to build on those.”

Finally, Stone says: “For me the most important lesson that Peter has ever taught me is that yeah, you’re important—but the world is important, and what are you going to do for it?

It’s a dialogue between you and your strengths and a world that needs them.” (calendarize this? #operacy )

#wb → why bother?

Bob Buford

Bob Buford ran a multimillion-dollar cable-television company, which he sold in 1999, and was the founding chairman of the Peter F. Drucker Foundation for Nonprofit Management.

Today he has a family foundation; he leads an organization that applies management talent to “megachurches” in the United States; he has written three books; and he runs Halftime.org, which provides seminars to people in midlife looking to shift “from success to significance,” he says.

When Buford initially called on Drucker, in the early 1980s, his ostensible goal was help with business issues.

But that was something of a ruse, he admits.

What he really wanted help on was what he should do with the rest of his life.

He got rather more than he bargained for.

Drucker’s secret to great mentoring, says Buford, is that he “has the most comprehensive, 50,000-foot view of how the world works, on one extreme.

On the other extreme, he’s incredibly personal in his mentoring.

He joins those two points of view.

He describes himself as a social ecologist, and as such, he’s always thinking about how things (past, present, future, people, knowledges, skills, organizations, society, polity …) fit together.”

Writing timeline

Buford needed both perspectives.

In January 1987, when he was 47, his only child, a 24-year-old son, drowned.

Later that year, Buford himself narrowly escaped dying.

He was supposed to take a trip in a small private plane but didn’t go.

The plane crashed, and four of his friends died.

“After all of that, I went to see Peter,” he says.

Understandably, Buford was feeling vulnerable and scared.

According to him, Drucker said, “I know you are feeling a heightened sense of your own mortality right now, but the fact is, you have 25 years or more of your life yet to be lived, and they will be the best 25 years of your life.”

Says Buford, “He essentially said, ‘Put your feet on the ground and get about your work,’ and that’s what I did.”

Later, Drucker helped Buford put his own midlife questioning into a larger context.

Drucker sketched out “what the social landscape looked like,” says Buford.

“The big demographic factor in the developed world has been the baby boom.

Everyone’s entering midlife, and they all don’t have a clue what to do—they’re all utterly unprepared.

He told me that he felt I’d done a good job in that area.

A lot of that was taking his advice.

I felt I had a responsibility to write a lot of that down.”

Drucker encouraged him in his writing, and the result was Buford’s 1995 best-seller Halftime.

“Peter’s great gift to me is to say ‘You can do it.’

Here’s this utterly Olympian figure telling little me that I can do it.”

Drucker and Me ← Bob Buford

«§§§»

Much of Drucker’s advice sounds simple.

How hard can it be to become an Über mentor, À la Drucker?

It’s impossible, says Buford: “There will never be another Peter Drucker.”

Still, mentors and those being mentored can learn from his techniques, which include:

He listens carefully and asks a lot of questions — Drucker’s approach. He listens carefully and asks a lot of questions — Drucker’s approach.

He brings a wealth of knowledge to bear in conversations with his advisees. He brings a wealth of knowledge to bear in conversations with his advisees.

He’s a Renaissance man who is incredibly well-read, draws upon an enormous breadth of experience, and has an astonishing memory.

He encourages people and helps them believe in themselves. He encourages people and helps them believe in themselves.

A Drucker truism: a good mentor or manager builds on people’s strengths and helps them make their weaknesses irrelevant.

He teaches people how to use their strengths so that they He teaches people how to use their strengths so that they

can fulfill their responsibility

to contribute to

a world that needs them.

He both defines the landscape and identifies what Buford calls “the void” in that landscape—what is needed now.

Finally, he works only with those people who take his counsel seriously and act on it. Finally, he works only with those people who take his counsel seriously and act on it.

As he wrote to us,

“One ‘secret’ of my work is that ...

I cannot work with more than a very small number of clients at any one time,

though once the relationship is established,

it tends to last for a long time—some for 30 years.

So I have the luxury to work only with people where both they and I feel that I can make a very major contribution.”

As, indeed, he has.

Elaine Appleton Grant is a senior editor at Inc. Staff writer Jill Hecht Maxwell contributed to this report.

No human being …

Social ecology ↑ ↓

Peter Drucker — timescape ↓

Social Needs and Business Opportunities

IMAGE THINKING

Edward de Bono

YouTube: A brief celebration of Edward de Bono's

ideas on thinking → IMAGE THINKING

Parallel Thinking

The Drucker Lectures:

Essential Lessons on

Management, Society, and Economy

The Definitive Drucker:

Challenges For

Tomorrow's Executives

#fastp ↑ ↓

Work has to make a LIFE

operacy

— the skills of doing need to be learned

Serious Outside Interest

↑ Inner worldS ↓ and ↑ outer worldS ↓

Post-capitalist executive

The memo THEY don’t want you to SEE

“For almost nothing in our educational systems

prepares people

for the reality in which they will live, work, and

become effective” — Druckerism and intellectual capitalist

“I believe that Drucker’s work was guided by one audacious overarching question: What does it take — what principles are needed — to make society both more productive and more humane?

… snip, snip …

For free society to function at its best — and to thereby compete with tyranny — we must have high-performing, freely-operating organizations spread throughout society; these autonomous institutions, in turn, depend on having excellent management.

This is a classic Druckerian duality, linking together big and small, practical and philosophical, micro and macro;

on the one hand, he stayed grounded in “what works” for managers, and

on the other hand, he framed “what works” in the context of one of the most important long-term questions that human societies must address.”

Jim Collins, author:

Built to Last,

Good to Great,

and How the Mighty Fall

“Peter was an original thinker, a self-created, one-of-a-kind individual who comes along every two or three centuries. …

He was an indefatigable observer of human nature and the interaction of human beings with one another and with circumstances.”

Bob Buford

“He normally begins about a thousand years away from the point and goes in a very wide loop that arrives at the point exactly.

He uses illustrations from many disciplines to shed light on the point he is making, and each story builds on the last.

He wants you to think about your situation in a larger context.”

Fred Smith

An introductory view of Drucker’s breadth of vision can be seen by quickly scrolling through:

A Functioning Society A Functioning Society

The (human) Ecological Vision The (human) Ecological Vision

The End of Economic Man (it’s probably in the today’s news) The End of Economic Man (it’s probably in the today’s news)

The first of three books that sketched a foundation for the world that emerged after World War II. The other books are The Future of Industrial Man (1942) and Concept of the Corporation — a society of organizations

Chapter 2, Drucker’s Vision of the New World in Drucker: The Man Who Invented the Corporate Society

Management — Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices — Revised Edition (a long, large partial view of the management thoughtscape) Management — Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices — Revised Edition (a long, large partial view of the management thoughtscape)

The Daily Drucker The Daily Drucker

Drucker & Me

“What a Texas Entrepreneur Learned

from the Father of Modern Management”

by Bob Buford

Author of Halftime, which has sold

more than 750,000 copies

The Essential Drucker answers the questions, “Where do I begin to read Drucker?” and “which of his writing is essential?”

A lot of people are confused by the word management.

Many assume or think that being given the title of manager instantly makes one a manager.

If that were the case how do we distinguish between those who actually manage and those who just have the title?

Also how do we differentiate between those in healthy, well performing institutions and sick institutions?

“Management, in most business schools, is still taught as a bundle of techniques, such as the technique of budgeting.

To be sure, management, like any other work, has its own tools and its own techniques.

But just as the essence of medicine is not the urinalysis, important though it is, the essence of management is not techniques and procedures.

The essence of management is to make knowledge productive.

Management, in other words, is a social function.

And in its practice, management is truly a “liberal art.” ”

From “A Century of Social Transformation”

“Indeed, the typical picture of what goes on in the “front office” or on “the fourteenth floor” in the minds of otherwise sane, well-informed and intelligent employees (including, often, people themselves in responsible managerial and specialist positions) bears striking resemblance to the medieval geographer’s picture of Africa as the stamping ground of the one-eyed ogre, the two-headed pygmy, the immortal phoenix and the elusive unicorn.”

“The human being has multiple characteristics and dimensions.

People are not only biological and physiological beings but also social, spiritual, and moral beings.

Individuals hold worldviews, beliefs about

the purpose of existence,

who they must ultimately answer to,

and what they are responsible for.

A person at work

is still a biological person

and a spiritual person,

and these dimensions combine

to guide her or his actions

throughout the day.

Management involves

an acknowledgment of

the multiple dimensions

of human beings.

Crucial, therefore, to understanding Drucker’s methodology

as a social ecologist

is grasping his assumptions

about the fundamental nature of the human being.

As discussed in Chapter 1, Drucker was so profoundly influenced by Kierkegaard

that he came to the same realization about human existence

as the Danish philosopher:

it is an existence in tension.

It consists of existence

in time — that is in society —

and in eternity where society is no longer relevant.

God is outside of time

and is eternal,

as is the soul of the individual.

Therefore, a true ecology of human-made existence

must take into account

the question of the existence of God

in order for man

to “fly right-side up.” source

“Management” means, in the last analysis, the substitution of thought for brawn and muscle, of knowledge for folklore and superstition, and of cooperation for force …

Supplying knowledge to find out how existing knowledge can best be applied to produce results is, in effect, what we mean by management.

“In my research,

I look at the trajectories

of technological improvement

and the trajectory of customers

to utilize improvement —

and those are constructs.

And the difficulty

of getting those right

is part of

why I admire Drucker’s accomplishment.

Because in essence, that is what

Peter Drucker did for mankind:

in every element of a manager’s life,

he gave us a construct

that allows us to think

about things differently.”

Clayton Christensen (“disruptive innovation” fame) —

quote source

“In the history of human thought there emerge, every now and then, individuals whose corpus of work brings into being a qualitative change in the knowledge and perceptions of the area of their concern.

And it’s a change for something infinitely better.

They redraw the boundaries of knowledge by their precise observation of empirical facts.

Peter Drucker was one of those rare beings.

He strove all his life to look out there, in the world, to derive ideas, challenging himself and those who came in his contact, “Look out the window, not in the mirror!” he fervently exhorted.

Drucker falls in line with thinkers like Charles Darwin, Sigmund Freud and Frederick Taylor.” more

The alternative to tyranny

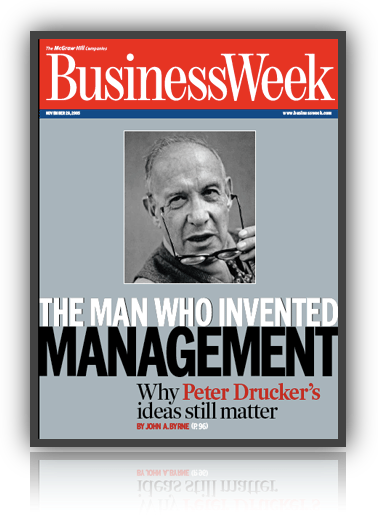

Drucker has been dead ~20 years and still has A top of the food chain reputation without equal.

Global Drucker Forum

Not a topic expert, other than how the world works.

He called himself a social ecologist — further down the page.

Not a theorist, but an involved practitioner — further down the page.

Not an answer provider, but a question poser, a thought stimulator, a human liberator.

Not an inside-outer, but an outside-inner.

Not a future forecaster, but an observer of the future that has already happened and an implication seer e.g., …

The dynamics of knowledge …

Knowledge doesn’t exist in schools, but in application and is therefore multi-disciplinary.

What matters are big tasks, work, outside end results.

Knowledge is constantly making itself obsolete and this creates social and economic shockwaves.

The imminent danger of good intentions!!!!

Post-Capitalist Society

The transformation: “Every few hundred years in Western history there occurs a sharp transformation … society rearranges itself … we are currently living through” … more

The society of organizations

… “I am often asked whether I am an optimist or a pessimist.

For any survivor of this century to be an optimist would be fatuous.

We surely are nowhere near the end of the turbulences, the transformations, the sudden upsets, which have made this century one of the meanest, cruelest, bloodiest in human history.”

…

Nothing “post” is permanent or even long-lived.

Ours is a transition period.

What the future society will look like, let alone whether it will indeed be the “knowledge society” some of us dare hope for, depends on how the developed countries respond to the challenges of this transition period, the post-capitalist period—their intellectual leaders, their business leaders, their political leaders, but above all each of us in our own work and life.

Yet surely this is a time to make the future—precisely because everything is in flux.

This is a time for action.

Outline of selected topics

«§§§»

… “Power has to be used.

It is a reality.

If the decent and idealistic toss power in the gutter, the guttersnipes pick it up — the antidote.

If the able and educated refuse to exercise power responsibly, irresponsible and incompetent people take over the seats of the mighty and the levers of power.

Power not being used for social purposes passes to people who use it for their own ends.

At best it is taken over by the careerists who are led by their own timidity into becoming arbitrary, autocratic, and bureaucratic.”

Management ≈ creating important results outside an organization;

organization performance;

making knowledge(s) productive;

pushing back the limitations and making the future …

Bailing out yesterday’s decisions ::: Making the future

Economic development

New paradigms

“He had an unparalleled grasp of the big picture”

A Functioning Society and The Ecological Vision — Bob Buford

Druckerisms

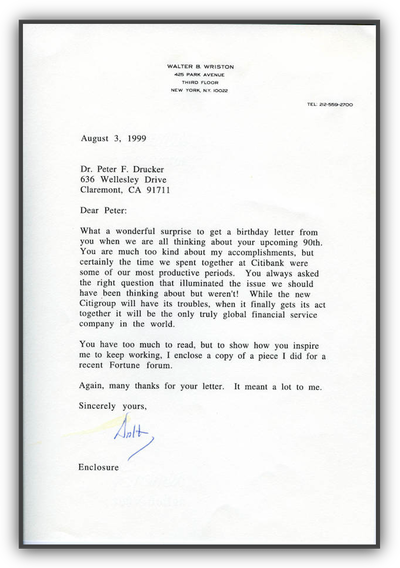

Why would someone like Walter Wriston

feel the need to bring in an outsider?

With his information and networking options,

why would he select anyone

other than the very best?

Larger view of the image above

CARE’s real mission

above … page 1 ::: page 2

“The more we dug into the formative stages and inflection points

of companies like General Electric, Johnson & Johnson,

Procter & Gamble, Hewlett-Packard, Merck and Motorola,

the more we saw Drucker’s intellectual fingerprints.

David Packard’s notes and speeches

from the foundation years at HP

so mirrored Drucker’s writings

that I conjured an image of Packard

giving management sermons

with a classic Drucker text in hand … ”

— Jim Collins author of

Built to Last, Good to Great,

and How the Mighty Fall

“No human being has built a better brand

by just managing himself” — later

Why Peter Drucker Distrusted Facts (HBR blog)

Chapter 3, “The Interpreter of Change” in Drucker: The Man Who Invented the Corporate Society

What Everybody Knows Is Frequently Wrong ::: If You Keep Doing What Worked in the Past You’re Going to Fail ::: Approach Problems with Your Ignorance—Not Your Experience ::: Develop Expertise Outside Your Field to Be an Effective Manager ::: Outstanding Performance Is Inconsistent with Fear of Failure ::: You Must Know Your People to Lead Them ::: People Have No Limits, Even After Failure ::: Base Your Strategy on the Situation, Not on a Formula — A Class With Drucker: The Lost Lessons of the World's Greatest Management Teacher

larger ↑

“I am not a ‘theoretician’; through my consulting practice I am in daily touch with the concrete opportunities and problems of a fairly large number of institutions, foremost among them businesses but also hospitals, government agencies and public-service institutions such as museums and universities.

And I am working with such institutions on several continents: North America, including Canada and Mexico; Latin America; Europe; Japan and South East Asia.” — PFD

In the words of Tom Peters: “Drucker effectively by-passed the intellectual establishment.

So it’s not surprising that they hated his guts.”

“He makes you think,” Jack Welch, then-chairman of General Electric Co., told the magazine, while Intel co-founder Andrew Grove declared, “Drucker is a hero of mine.

He writes and thinks with exquisite clarity—a standout among a bunch of muddled fad mongers.”

“He would never give you an answer.

That was frustrating for a while.

But while it required a little more brain matter, it was enormously helpful to us.

After you spent time with him, you really admired him not only for the quality of his thinking but for his foresight, which was amazing.

He was way ahead of the curve on major trends.”

“THE PRESIDENT knew the man needed no introduction, so, without a word of identification, he simply told the employees of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare assembled to hear his speech: “Peter Drucker says that modern government can do only two things well: wage war and inflate the currency.

It’s the aim of my administration to prove Mr. Drucker wrong.”

If Richard Nixon thought he did not have to identify Peter Drucker thirty years ago, must I do it now?

Drucker’s fame is planetary.

… snip, snip …

Drucker has been called everything from “the father of management” to “the man who changed the face of industrial America” to “the one great thinker management theory has produced.”

… snip, snip …

Peter Drucker’s influence is global: his twenty-nine books have sold over five million copies, and they have been translated into nearly every language in the world.

His views on management, industrial organization, business strategy, leadership development, and employee motivation have tutored not just companies but countries—Drucker served as a guru to the postwar Japanese economic miracle—and he has an earned reputation for forecasting future social and economic trends.

… snip, snip …

Drucker’s ideas and books gain authority from his work as a management consultant; for fifty years he has immersed himself in the management challenges of Fortune 500 corporations, museums, charitable foundations, churches, hospitals, small businesses, universities, governments, and even baseball teams—Yogi Berra was once a client.

… snip, snip …

… and notes the recurring paradox of Drucker’s career: the “man who invented the corporate society” has been a sometimes sulphuric critic of capitalist excess.

Indeed, Drucker, the author writes, should be seen as “a moralist of our business civilization””

The World According to Peter Drucker

by Jack Beatty

“ … Drucker belonged to the church of results.

Instead of starting with an almost religious belief in a particular category of answers—a belief in leadership, or culture, or information, or innovation, or decentralization, or marketing, or strategy, or any other category—Drucker began first with the question “what accounts for superior results?” and then derived answers.

He started with the outputs—the definitions and markers of success—and worked to discover the inputs, not the other way around.

And then he preached the religion of results to his students and clients, not just to business corporations but equally to government and the social sectors.

The more noble your mission, the more he demanded: what will define superior performance?

“Good intentions,” he would seemingly yell without ever raising his voice, “are no excuse for incompetence.”

And yet while practical and empirical, Drucker never became technical or trivial, nor did he succumb to the trend in modern academia to answer (in the words of the late John Gardner) “questions of increasing irrelevance with increasing precision.”

By remaining a professor of management—not as a science, but as a liberal art he gave himself the freedom to pursue audacious questions.

My first reading of Drucker came on vacation in Monterey, California.

My wife and I embarked on one of our adventure walks through a used book store, treasure hunting for unexpected gems.

I came across a beaten-up, dog-eared copy of Concept of the Corporation, expecting a tutorial on how to build a company.

But within a few pages, I realized that it asked a much bigger question: what is the proper role of the corporation at this stage of civilization?

Drucker had been invited to observe General Motors from the inside, and the more he saw, the more disturbed he became.

General Motors … can be seen as the triumph and the failure of the technocrat manager,” he later wrote.

“In terms of sales and profits [GM) has succeeded admirably … But it has also failed abysmally—in terms of public reputation, of public esteem, of acceptance by the public.”

Drucker passionately believed in management not as a technocratic exercise, but as a profession with a noble calling, just like the very best of medicine and law.

Drucker could be acerbic and impatient, a curmudgeon.

But behind the prickly surface, and behind every page in his works, stands a man with tremendous compassion for the individual.

He sought not just to make our economy more productive, but to make all of society more productive and more humane.

To view other human beings as merely a means to an end, rather than as ends in themselves, struck Drucker as profoundly immoral.

And as much as he wrote about institutions and society, I believe that he cared most deeply about the individual.” more

Jim Collins author of

Built to Last, Good to Great,

and How the Mighty Fall

“To know something,

to really understand something important,

one must look at it from sixteen different angles.” — PFD

Remembering Peter Drucker from the November 2009 issue of The Economist. Remembering Peter Drucker from the November 2009 issue of The Economist.

Drucker → A Social Ecologist Drucker → A Social Ecologist

It also implies that society, polity and economy are a genuine environment, a genuine whole, a true “system,” to use the fashionable term, in which everything relates to everything else and in which men, ideas, institutions, and actions must always be seen together in order to be seen at all, let alone to be understood.

... snip, snip ...

Political ecologists believe that the traditional disciplines define fairly narrow and limited tools rather than meaningful and self-contained areas of knowledge, action, and events — in the same way in which the ecologists of the natural environment know that swamp or the desert is the reality and ornithology, botany, and geology only special-purpose tools.

... snip, snip ...

Political ecologists are uncomfortable people to have around.

Their very trade makes them defy conventional classifications, whether of politics, of the market place, or of academia.

See assumptions

... snip, snip ...

It would be difficult to say, I submit, which of chapters in this volume are “management,” which “government” or “political theory,” which “history” or “economics.”

The task determines the tools to be used: but this has never been the approach of academia — knowledge exists only in application.

Connections: here and the primacy of knowledge below

The transformation — Post-Capitalist Society The transformation — Post-Capitalist Society

Introduction to the Transaction Edition of The End of Economic Man: The Origins of Totalitarianism Introduction to the Transaction Edition of The End of Economic Man: The Origins of Totalitarianism

The Alternative to Tyranny The Alternative to Tyranny

Hemme and Genia — Adventures of a Bystander Hemme and Genia — Adventures of a Bystander

Landmarks of Tomorrow Landmarks of Tomorrow

Up to Poverty — the agents of revolution Up to Poverty — the agents of revolution

The Vanishing East — the end of the European power system The Vanishing East — the end of the European power system

Technology, Management and Society Technology, Management and Society

Exploring with Essays Exploring with Essays

The Manager and the Moron The Manager and the Moron

The First Technological Revolution and its Lessons The First Technological Revolution and its Lessons

Technology (more than you might think) Technology (more than you might think)

The Definitive Drucker The Definitive Drucker

… but then the world got a lot more complicated … but then the world got a lot more complicated

What Needs to Be Done What Needs to Be Done

The Primacy of Knowledge The Primacy of Knowledge

How to guarantee non-performance and What results should you expect? — a user’s guide to MBO How to guarantee non-performance and What results should you expect? — a user’s guide to MBO

Organization actions: creating change to abandonment Organization actions: creating change to abandonment

From Analysis to Perception — The New Worldview From Analysis to Perception — The New Worldview

Knowledge and Technology Knowledge and Technology

Josh Abrams: Life-long self development Josh Abrams: Life-long self development

Mission Mission

Ten Principles for Life II Ten Principles for Life II

The Wisdom of Peter Drucker The Wisdom of Peter Drucker

The World is Full of Options The World is Full of Options

My life as a knowledge worker My life as a knowledge worker

Peter's Principles — no human being has built a better brand by just managing himself Peter's Principles — no human being has built a better brand by just managing himself

Interview: Post-Capitalist Executive Interview: Post-Capitalist Executive

Interview: Managing in a Post Capitalist Society Interview: Managing in a Post Capitalist Society

The Effective Executive The Effective Executive

The Tasks of the Manager The Tasks of the Manager

Unleash yourself (from being a prisoner of the past) Unleash yourself (from being a prisoner of the past)

Drucker’s Lost Art of Management Drucker’s Lost Art of Management

Books by Peter Drucker Books by Peter Drucker

More links at the bottom of this page More links at the bottom of this page

Elizabeth Haas Edersheim wrote the following in The Definitive Drucker:

While interviewing former students and clients, I noticed a pattern.

Virtually everyone I interviewed said, at some time in the interview, one version or another of essentially the same thing:

“Peter liberated me.

He elevated my expectations.”

I never really understood the power of liberation until I started hearing stories about it from so many people.

The return on luck

Peter’s ideas were the catalyst that freed people (from being prisoners of the past) to pursue opportunities they had never expected to have.

He liberated people by asking them questions and eliciting a vision that just felt right.

He liberated people by getting them to challenge their own assumptions.

He liberated people by raising their awareness of, and their faith in, things they knew intuitively.

He liberated people by forcing them to think.

He liberated people by talking to them.

He liberated people by getting them to ask the right questions.

When I played this theme back to Warren Bennis, a longtime friend of Peter’s and one of today’s leading thinkers on organizational effectiveness, he responded, “Yes, I had never thought of it that way, but Peter Drucker does liberate.”

Warren sat back in his living room chair and smiled.

When I checked it with Richard Cavanagh, president of the Conference Board, he smiled and said, “Yes, I’ve seen him do that a lot.

I’ve even seen him liberate whole audiences as he spoke.”

A particularly poignant moment came when I was interviewing Tony Bonaparte, special assistant to the president at St. John’s University in New York.

With tears in his eyes, he looked at me and told me how Drucker had changed his career and his life.

Bonaparte had always wanted to teach at a community college.

He had a chance to attend the Executive MBA program at NYU.

There he met Drucker, who was a professor and teaching an evening class.

Drucker took an interest in him, and Peter and Doris started taking him out to dinner every few weeks.

Drucker would ask questions and implore Bonaparte to push, push, push to liberate himself.

“He made sure I always was stretching just a little further, liberating me from my constraints,” Bonaparte remembered.

“Each time I went back, my expectations of myself were higher.

He would not let me do anything but succeed.

And if it weren’t for him I wouldn’t be where I am today.

He looks at things as they are with a very realistic sense of how they could be and helped me do the same.

It changed my life.”

Drucker worked with great leaders for over 75 years and liberated them, too.

Churchill went so far as to say that the amazing thing about Peter Drucker was his ability to start our minds along a stimulating line of thought.

Mexican President Vicente Fox commented that Peter’s insights on societies were second to none.

Peter Drucker so increased the credibility of the concept of “management” that the U.S. Bureau of the Budget was renamed the Office of Management and Budget in 1970.

And, of course, Drucker liberated and inspired great corporate leaders, among them Akito Morita, founder of Sony; Andy Grove, one of the founders of Intel; Bill Gates of Microsoft; and Jack Welch, former chairman and chief executive of General Electric.

|

![]()