Water logic

By Edward de Bono (includes links to many of his other books)

Amazon link: Water logic

Water Logic Explored

Contents

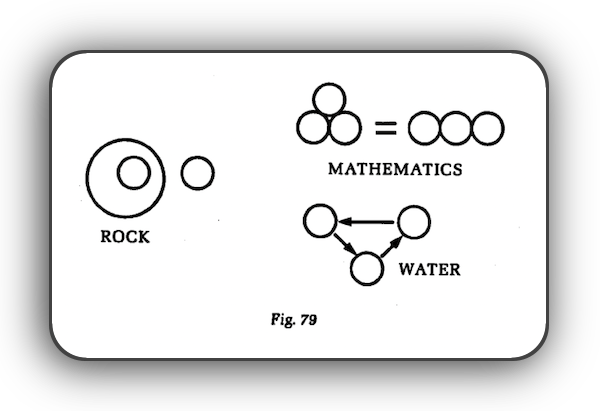

At several points in the book I have referred to ‘water logic’ as a contrast to the ‘rock logic’ of traditional thinking.

The purpose of this naming of ‘water logic’ is to give an impression of the difference.

At this point I shall spell out in more detail some of the points of difference.

A rock is solid, permanent and hard.

This suggests the absolutes of traditional thinking (solid as a rock).

Water is just as real as a rock but it is not solid or hard.

The permanence of water is not defined by its shape.

A rock has hard edges and a definite shape.

This suggests the defined categories of traditional thinking.

We judge whether something fits that category shape or not.

Water has a boundary and an edge which is just as definite as the edge of a rock, but this boundary will vary according to the terrain.

Water will fill a bowl or a lake.

It adapts to the terrain or landscape.

Water logic is determined by the conditions and circumstances.

The shape of the rock remains the same no matter what the terrain might be.

If you place a small rock in a bowl, it will retain its shape and make no concession at all towards filling the bowl.

The absolutes of traditional thinking deliberately set out to be circumstance-independent.

If you add more water to water, the new water becomes part of the whole.

If you add a rock to a rock, you simply have two rocks.

This addition and absorption of water logic corresponds to the process of poetry, in which new images become absorbed in the whole.

It is also the basis of the new artificial device of the ‘strata!’.

With conditions and circumstances, the addition of new circumstances becomes part of the whole set of circumstances.

We can match rocks by saying this shape ‘is’ or ‘is not’ the same as another shape.

A rock has a fixed identity.

Water flows according to the gradient.

Instead of the word ‘is’ we use the word ‘to’.

Water flows ‘to’ somewhere.

In traditional (rock) logic we have judgements based upon right/wrong.

In perception (water) logic we have the concepts of ‘fit’ and ‘flow’.

The concept of ‘fit’ means:

‘Does this fit the circumstances and conditions?’

The concept of ‘flow’ means:

‘Is the terrain suitable for flow to take place in this direction?’

Fit and flow both mean the same thing.

Fit covers the static situation, flow covers the dynamic situation.

Does the water fit the lake or hole?

Does the river flow in this direction?

Truth is a particular constellation of circumstances with a particular outcome.

In this definition of truth we have both the concepts of fit (constellation of circumstances) and of flow (outcome).

In a conflict situation both sides are arguing that they are right.

This they can show logically.

Traditional thinking would seek to discover which party was really ‘right’.

Water logic would acknowledge that both parties were right but that each conclusion was based on a particular aspect of the situation, particular circumstances, and a particular point of view.

‘TO’

What do we mean by ‘to’?

A ball on a slope rolls ‘to’ or towards the bottom of the slope.

A river flows ‘to’ the sea.

A path leads ‘to’ some place.

An egg in a frying-pan changes ‘to’ a fried egg.

A falling egg leads ‘to’ the mess of a broken egg on the carpet.

A film director may cut from a shot of a falling egg ‘to’ a shot of a collapsing tower.

A film director may cut from a shot of a falling egg ‘to’ a shot of an anguished girl.

A ball that rolls ‘to’ a new position is still the same ball.

The raw egg that becomes the fried egg is still the same egg in a different form.

But the shot of the collapsing tower or the anguished girl in the film is only related to the prior shot of the falling egg because the director has chosen to relate them.

So we really use ‘to’ in a number of different ways.

Throughout this book I intend to use ‘to’ in a very simple and clear sense:

what does this lead to?

What happens next?

It simply means what happens next in time.

If a film image of an egg is followed by the image of an elephant then the egg leads to the elephant.

If you are being driven in a car along a scenic route and an idyllic shot of a cottage is followed by a view of a power station, then that is what happens next.

So the sense of ‘to’ is not limited to ‘becoming’ or ‘changing to’, although this will also be included in the very broad definition of ‘to’ as what happens next.

An unstable system can become a stable system.

A stable system can become an unstable system.

One thing leads to another.

Because this notion of ‘to’ is so very important it would be useful to define it precisely with a new word.

Perhaps we could create a new preposition, ‘leto’, to indicate ‘leads to’.

At this point in time it would sound only artificial and unnecessary

1. FOREWORD

Johnny was a young boy who lived in Australia.

One day his friends offered him a choice between a one dollar coin and a two dollar coin.

In Australia the one dollar coin is considerably larger than the two dollar coin.

Johnny took the one dollar coin.

His friends giggled and laughed and reckoned Johnny very stupid because he did not yet know that the smaller coin was worth twice as much as the bigger coin.

Whenever they wanted to demonstrate Johnny’s stupidity they would repeat the exercise.

Johnny never seemed to learn.

One day a bystander felt sorry for Johnny and beckoning him over, the bystander explained that the smaller coin was actually worth twice as much as the larger coin.

Johnny listened politely, then he said: ‘Yes, I do know that.

But how many times would they have offered me the coins if I had taken the two dollar coin the first time?’

A computer which has been programmed to select value would have had to choose the two dollar coin the first time around.

It was Johnny’s human ‘perception’ that allowed him to take a different and longer-term view: the possibility of repeat business, the possibility of several more one dollar coins.

Of course, it was a risk and the perception was very complex: how often would he see his friends?

Would they go on using the same game?

Would they want to go on losing one dollar coins, etc.?

There are two points about this story which are relevant to this book.

The first point is the great importance of human perception, and that is what this book is about.

Perception is rather different from our traditional concept of logic.

The second point arising from the story is the difference between the thinking of Johnny and the thinking of the computer.

The thinking of the computer would be based on ‘is’.

The computer would say to itself:

‘Which of the two coins “is” the most valuable?’

As a result the computer would choose the smaller, two dollar coin.

The thinking of Johnny was not based on ‘is’ but on ‘to’:

‘What will this lead to?’

‘What will happen if I take the one dollar coin?’

Traditional rock logic is based on ‘is’.

The logic of perception is water logic and this is based on ‘to’.

The basic theme of the book is astonishingly simple.

In fact it is so simple that many people will find it hard to understand.

Such people feel that things ought to be complex in order to be serious.

Yet most complex matters turn out to be very simple once they are understood (here, here, and here).

Because the theme is so simple I shall attempt to describe it as simply as possible.

Although the basic theme is simple the effects are powerful, important and complex.

I have always been interested in practical outcomes. (Find practical outcomes here)

There are many practical processes, techniques and outcomes covered in this book.

How would you like to ‘see’ your thinking as clearly as you might see a landscape from an aeroplane?

There is a way of doing that which I shall describe.

This can be of great help in understanding our perceptions and even in altering them.

I know that my books attract different sorts of readers.

There are those who are genuinely interested in the long neglected subject of thinking and there are those who are only interested in practical ‘hands-on’ techniques.

The latter type of reader may be impatient with the underlying theory, which is seen to be complex and unnecessary.

I would like to be able to say to this sort of reader: ‘Skip section ...

and section ...’

But I will not do that because thinking has suffered far too much from a string of gimmicks that have no foundation.

It is very important to understand the theoretical basis in order to use the processes with real motivation.

Furthermore the underlying processes are fascinating in themselves.

Understanding how the brain works is a subject of great interest.

I have used no mathematical expressions in the book because it is a mistake to believe that mathematics (the behaviour of relationships and processes within a defined universe) has to be expressed in mathematical symbols which most people do not understand.

Some years ago Professor Murray Gell-Mann, the California Institute of Technology professor who won a Nobel prize in physics for inventing/discovering/describing the quark, was given my book The Mechanism of Mind which was published in 1969.

He told me that he had found it very interesting because I had ‘stumbled upon processes ten years before the mathematicians had started to describe them’.

These are the processes of self-organizing systems which interested him for his work on chaos —try an Amazon search.

This book is a first look at water logic and my intention has been to put forward a method for using it in a practical manner.

2. INTRODUCTION

This book is closely related to my previous book I am Right - You are Wrong (London: Viking, 1990 and Penguin 1991).

In that book I set out to show that the traditional habits of Western thinking were inadequate and how our belief in their adequacy was both limiting and dangerous.

These traditional habits include: the critical search for the ‘truth’; argument and adversarial exploration, and all the characteristics of rock logic with its crudities and harshness.

These habits of thinking were ultimately derived from the classic Greek gang of three, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, who hijacked Western thinking.

After the dogma of the Dark Ages, the rediscovery of this classical thinking was indeed a breath of fresh air and so these habits were taken up both by the Church (to provide a weapon for attacking heresy) and by the non-Church humanist thinkers to provide an escape from Church dogma.

So it became the established thinking of Western civilization.

Unfortunately this thinking lacks the creative, design and constructive energies that we so badly need.

Nor does this thinking take into account the huge importance of perception, beliefs and local truths.

Finally this rock logic exacerbates the worst deficiencies of the human brain, which is why we have made progress in technical matters and so little in human affairs.

For the first time in history we do know something, in broad terms, about how the brain works as a self-organizing information system - and this has important implications.

As I predicted the book was met with outrage that was so hysterical that it became comic and ludicrous rather than offensive.

Not one of those who attacked the book ever challenged its basic themes.

The attacks were in the nature of childish personal abuse or picked on very minor matters - which is always a sure indication that the reviewer is not reviewing the book but prefers to attack the author.

This is a pity because it is a serious subject which needs much more attention than it gets.

It was Einstein who once said: ‘Great spirits have always encountered violent opposition from mediocre minds.’

It does not follow that violent opposition from mediocre minds qualifies one automatically as a great spirit but it does suggest that the violence of the opposition sometimes indicates emotions rather than value.

To redress this balance, because the subject is important, I invited three Nobel prize physicists to write forewords to the book for future editions.

Those forewords put the matter into perspective.

Why physicists?

Because physicists spend their whole lives looking at fundamental processes and their implications.

I had intended to add a section on water logic and ‘hodics’ to the book.

In the end the book became too long and it was obvious that the section would have to be too short to do justice to the subject.

I promised I would treat the subject in a subsequent publication, and that is what this book is about.

In our tradition of thinking we have sought to get away from the vagueness and instability of perception in order to deal with such concrete matters as mathematics and logic.

We have done reasonably well at this and can now get back to dealing with perception as such.

Indeed we have no choice because if our perceptions are faulty then perfect processing of those faulty perceptions can only give an answer that is wrong, and sometimes dangerous.

We know from experience that both sides in any war, conflict or disagreement always have ‘logic’ on their side.

This is true: a logic that serves their particular perceptions.

So this book is about the water logic of perception.

How do perceptions come about?

What is the origin and nature of perception?

How do the nerve circuits in the brain form and use perceptions?

How do perceptions become stable - and stable enough to become beliefs?

Can we get to look at our perceptions regarding any particular matter?

Can we change perceptions—and if so, where do we start?

This book does not provide all the answers but at the end of it the reader should have a good understanding of the difference between water logic and rock logic. …

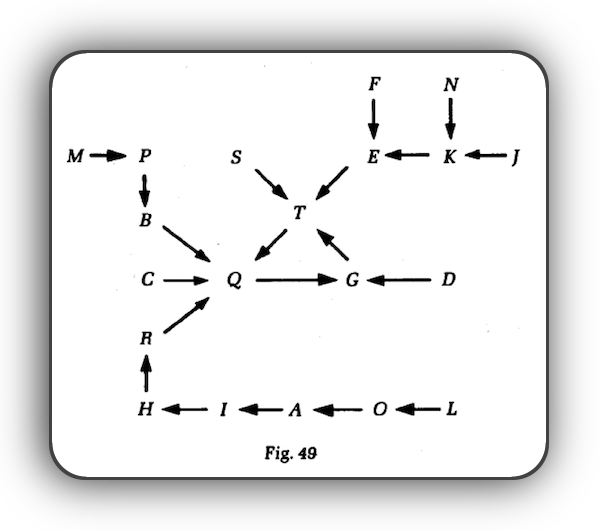

Choosing a holiday base list

A COST → I

B CLIMATE → Q

C LOW HASSLE → Q

D GOOD COMPANY → G

E ACTIVITIES → T

F SIGHTSEEING → E

C RELAXING → T

H SOMETHING TO TALK ABOUT → R

I AGREEMENT OF ALL PARTIES → H

J EXPERIENCE → K

K PRIOR KNOWLEDGE → E

L TOLERANCE → O

M PLAN AHEAD → P

N ADVICE → K

0 RISK → A

P TIME OF YEAR → B

Q INTERESTS → G

R ANTICIPATION → Q

S HEALTH → T

T ENERGY → Q

Choosing a holiday flowscape

See Peter Drucker's From Analysis to Perception—The New Worldview and The Educated Person for relevance connections. Chapters on these topics can be found in several of Drucker's books. Both can be found in The Essential Drucker.

3. Structure of the book

I start by considering the importance of perception which is the working of the inner world of the mind.

This is different from the outer world which surrounds us.

Traditionally we have tried to get away from perception to deal with the ‘truth’ of reality.

It is time we looked directly at perception.

The next section introduces the notion of water logic and ‘flow’.

Traditional logic is rock logic and is based on ‘is’ and identity.

Water logic is based on ‘to’: what does this flow to?

An analogy involving the behavior of simple jellyfish then illustrates how ‘flow’ works to give stability in a self-organizing system.

Different flow patterns are illustrated.

There is now a direct consideration of the ‘flow behavior’ of the brain and how this gives rise to perception.

The jellyfish analogy is transferred to the behavior of nerve circuits in the brain but the principles remain the same.

A practical technique called the ‘flowscape’ is now introduced.

This technique enables us to see the ‘shape’ of our perceptions.

I explain how flowscapes are created.

A stream of consciousness provides the items for the ‘base list’ from which the flowscape is derived.

The nature of this list is discussed.

There follows a consideration of flowscapes that are more complex, with comments upon these.

The next section deals with the great importance of concepts in water logic and in perception.

Concepts give us flexibility and movement in thinking.

These concepts do not need to be precise and a little fuzziness is beneficial.

We may want to see how we might intervene to alter perceptions.

This section is concerned with methods of intervention based on the flowscape.

Although the flowscapes are concerned with the inner world of perception, we can derive from the flowscapes some strategies for dealing with the outer world.

The notion of context is central to water logic because if the context changes then the flow direction may also change.

This is very different from the assumed absolutes of rock logic.

Being based on perception, flowscapes are highly personal.

Nevertheless, it is possible to attempt to chart the perceptions of others.

This can be done in a number of ways ranging from discussion to guessing.

Even guessing can suggest usable strategies.

The flow of our attention over the outer world is strongly influenced by the perceptual patterns we have set up in the inner world.

This is considered in this section as is the relationship between art and attention flows.

The practical difficulties that might be encountered in setting up flowscapes are now considered with some suggestions as to how they might be overcome.

The summary pulls together the nature of water logic and the practical technique of the flowscape.

Water logic does not exist only as a contrast to rock logic.

Edward de Bono

Palazzo Marnisi

Malta

4. Outer world — inner world

The original title of this section was going to be ‘Perception and Reality’.

In the traditional way this would have suggested that there was reality ‘somewhere out there’ and then there was perception which was different from reality.

But perception is just as real as anything else — in fact perception is more real for the person involved.

A child’s terror at a moving curtain in the night is very real.

A schizophrenic’s anguish at inner voices is very real.

In fact, perception is the only reality for the person involved.

It is not usually a shared reality and may not check with the world out there, but perception is certainly real.

From Analysis to Perception

↑ We live in the world

WE SEE

For centuries Western thinking has been dominated by the analogy of Plato’s cave in which a person chained so that he can only see the back of the cave, sees only the shadows projected on this surface and not the ‘reality’ that has caused the shadows.

So philosophers have generally looked for the ‘truth’that gives rise to these shadows or perceptions.

It is quite true that some people, like Freud and Jung in particular, focused their attention on the shadows, but not on perception in general.

This lack of interest in perception is understandable.

People wanted to get away from the messiness of perception to the solidity of truth.

More importantly, you cannot do much except describe perceptions unless you have some understanding of how they work.

That understanding we have come to only very recently.

A Georgian manor house is set on its own in the fields.

A party of people arrive for the weekend.

They are all looking at the same house.

One person looks at it with nostalgia for happy times spent there.

Another person looks at it with envy, thinking of the sort of life style she would want.

A third person looks at it with horror, remembering a harsh childhood spent in the house.

A fourth person immediately assesses how much such a house would cost.

The house is the same in each case and a photograph taken by each of the people would show the same house.

But the inner world of perception is totally different.

In the case of the house seen differently the physical view is the same but the memory trails and emotional attachments provide the different inner world of perception.

But perception could still be different even if there were no special memory trails.

If each of the guests were to approach the house from a different direction they would get a different point of view.

It would be the same house perceived from a different perspective.

The person approaching from the front would get the classic Georgian facade.

A person approaching from the side would see the original Elizabethan house on to which the facade had been tacked.

The person approaching from the back might mistake the house for a farm.

Everyone knows of the classic optical illusions in which you look at a drawing on a piece of paper and what you think you see is not actually the case: lines which seem to bend but are actually straight; a shape that looks larger than another but is exactly equal.

Stage magicians perform the magnificent feat of fooling all the people all the time through tricking their perceptions.

We are left waiting for the event to occur while it has occurred a long time before.

It is obvious that perception is very individual and that perception may not correspond with the external world.

Perception, in the first place, is the way the brain organizes the information received from the outer world via the senses.

The type of organization that is possible depends entirely on the fundamental nature of the nerve circuits in the brain.

This organization is then affected by the emotional state of the moment which favors some patterns at the expense of others.

The short-term memory of the present context and what has gone immediately before affects perception.

Computer translation of language is so difficult because what has gone before, and the context, may totally alter the meaning of the word.

For example, the word ‘live’ is pronounced in two different ways depending on the context.

Finally there are the old memories and memory trails which can both alter what we perceive and attach themselves to the perception.

One of the most striking examples of the power of perception is the phenomenon of jealousy.

A man is accused of choosing to sit in a certain place in a restaurant so that he can stare at the blonde sitting opposite.

In truth, he had not even noticed the blonde and was really trying to give his girlfriend the seat with the best view.

A wife seems to be seeing a lot of a certain man in the course of her business.

She claims it is a business relationship but her husband thinks otherwise.

In jealousy there are complex interpretations of normal situations which may be totally false and yet give rise to powerful emotions, quarrels and violence.

The point is that the perceptions could, just possibly, be true.

The fact that they are not true does not alter the perceptions.

It is no wonder that the ancient thinkers considered it a magnificent feat to get away from this highly subjective business of perception to truths and absolutes which could be checked and which would hold for everyone.

If you were making a table you could guess the sizes of the pieces that you needed and just cut them up according to your guess.

You would probably be better off if you were to measure the pieces you needed.

They would then be more likely to fit together and the table legs would be the same height.

Measurement is a very successful way of changing perception into something that is concrete, tangible and permanent.

We take it for granted but it is a wonderful concept.

Mathematics is another method for escaping the uncertainties of perception.

We translate the world into symbols and relationships.

Once this is done we enter the ‘game world’ of mathematics with its own special universe and rules of behavior within that universe.

We play that game in a rigorous manner.

Then we translate the result back into the real world.

The method works very well indeed provided the mathematics is appropriate and the translation into and out of the system is valid.

The great contribution of the Greek gang of three was to set out to do the same thing with language.

Words were going to have specific definitions and to be as real, concrete and objective as is measurement.

Then there was going to be a rigorous game with rules which would tell us how to put words together and how to reason.

This game was largely based on identity: this thing ‘is’ or ‘is not’ something else.

The principle of contradiction held that something could not ‘be’ and ‘not be’ something at the same time.

From this basis we developed our systems of language, logic, argument, critical thinking and all the other habits which we use all the time.

The result was that we seemed able to make judgements (which the human brain loves) and to arrive at truths and certainties.

This was all very attractive and it was very successful when applied to technical matters.

It seemed successful when applied to human affairs because judgement and certainty gave a basis for action and for righteousness.

In fact this habit of ‘logic’ is no less a belief system than any other.

If you choose to look at the world in a certain way then you will reinforce your belief by seeing the world in that way.

So the trend has been to flee the world of perception in terms of thinking and to leave perception to art which could explore and elaborate perceptions at will.

I believe it is time we did turn our attention to the world of perception in order to understand what actually happens in that world.

The world of perception is closely related to the way the brain handles information and that is what I explore in the book I am Right - You are Wrong.

There is no ‘game truth’ in perception as there is in mathematics where something is true because it follows from the rules of the game and the universe.

All truth in perception is either circular or provisional.

Circular truth is like two people each telling the other that he or she is telling the truth.

Provisional truth is based on experience:

‘it seems to me’;

‘as far as I can see’;

‘in my experience’.

There is none of that wonderful certainty which we have with ordinary logic — which is a ‘belief truth’ that masquerades as a ‘game truth’.

In the inner world of perception there is not the solidity and permanence of ‘rock logic’.

A rock is hard, definite and permanent, and does not shift.

This is the logic of ‘is’.

Instead, perception is based on water logic.

Water flows.

Water is not definite and hard edged but can adapt to its container.

Water logic is based on ‘to’.

The purpose of this book is to explore the nature and behavior of water logic and to demonstrate some practical ways of using it.

Water logic is the logic of the inner world of perception.

I suspect that it also applies, far more than we have hitherto thought, to the external world as well.

As we start to examine self-organizing systems, as mathematics begins to look into non-linear systems and chaos, so we shall find that water logic is also relevant to many aspects of the external world to which we have always applied rock logic.

I believe this to be the case with economics.

There is a direct impact of perception and water logic even on the apparent rock logic of science.

The mind can see only what it is prepared to see.

The analysis of data does not, by itself, produce ideas.

The analysis of data can only allow us to select from existing ideas.

There is a growing emphasis on the importance of hypotheses, speculation, provocation and model building, all of which allow us to see the world differently.

The creation of these frameworks of possibility is a perceptual process.

I should add that there is no such thing as a contradiction in perception.

Opposing views may be held in parallel.

There is mismatch where something does not fit our expectations — like a black four-of-hearts playing card but that is another matter.

Because of this ability of perception to hold contradictions, logic has been a very poor way of changing perceptions.

Perceptions can be changed (by exploration, insight, context changes, atrophy, etc.) but not by logic.

That is another very good reason for getting to understand perception.

Only a very small part of our lives is spent in mathematics or logical analysis.

By far the greater part is spent dealing with perception.

What we see on television and how we respond to it, is perception.

Our notions of ecological dangers and the greenhouse effect are based on perception.

Prejudice, racism, anti-semitism are all matters of perception.

Conflicts that are not simply bully-boy power plays are based on misperceptions.

Since perception is so important a part of our lives there seems merit in examining the nature of water logic rather than trying still harder to fit the world into our traditional rock logic.

Concepts

Legal documents often contain paragraphs like,

'The house at number 14 Belmont Road,

the house at number 41 Cornwall Avenue

and the house at number 12 Drake Street

comprise the property hereinafter referred to as The Property.'

So instead of listing the different houses each time they are referred to, it is only necessary to write 'The Property'.

A concept is a similar package of convenience

which puts a number of things together

so that they can be referred to as a whole.

In a sense every word is a concept.

There is a concept of a mountain which is referred to by that word.

There is the concept of justice

which includes

fair play,

moral values

and the administration of the law.

Obviously it is easier to be certain about

what goes into a concept

where the subject is physical

and can be observed

than when it is abstract.

A great deal of

classic Greek thinking

and Socratic dialogue

went into discussing and arguing

about

what actually

should go into concepts

such as justice.

So there are concepts

which have been crystallized

into words:

crime, justice, punishment, mercy, etc.

Then there are packages

for which we do not yet have a word.

This may be

because it is but a temporary package (as with the legal document)

or because language is quite slow at creating and admitting new words.

We could call these 'naked' concepts

since they are like a crab

without

the hard shell of a word around them.

Such naked concepts have to be described by a phrase,

a combination of other words.

All the

stream of consciousness lists

given in this book

contain a variety of concepts.

These may be well established concepts

like COST or SOCIAL STATUS.

There are also less established concepts

such as LOW HASSLE and HEROIC MEDICINE.

There may even be

more complicated concepts

like

HIGH COST OF LAST MONTH OF LIFE.

This last example

is on the borderline

between

a described factor

and a concept.

As I have indicated

there is some danger

if the concepts

we use in the base list

are too broad.

For example,

in the flowscape on

'Choosing a holiday'

if we had inserted

the concept

ENJOYABLE

we might have ended up

with showing that

the best way

to choose a holiday

was to choose

an enjoyable holiday.

This is like saying

the best holiday

is the best one to choose.

The same consideration

applied to

'Choosing a career'.

If we had inserted the concept

SUITS ME BEST

we would have arrived

at the conclusion

that the best career

was the one which

suits a person best.

Since this is just a

repeat of the question

it has little practical value.

For the base lists

we need to

put in

concepts

that are broad enough

to cover a lot of detail

but not so broad

that they just

repeat the question:

'How would you solve this problem?'

'With the appropriate answer.'

In addition to using concepts for the base list

we can also extract concepts

from the flowscape

when

we have it before us.

Any major collector point

is automatically

a useful concept

which may, or may not, be

adequately described

by the item on the base list.

For example,

in 'Choosing a holiday'

the point INTERESTS

is a major collector point.

We may leave this as it is

or redefine it.

Sometimes

a whole loop

can become a concept.

For example,

in the 'Health care costs' flowscape

the whole stable loop could be

characterized as

'the need to strive to maintain life

at any cost'.

This is not quite the same

as heroic medicine,

though this comes into it.

The concept of

'health as a right'

is produced by

a combination of

demands,

expectations

and lack of economic considerations.

One of the main benefits

of examining flowscapes

is to realize

how powerful

certain clusterings

of factors

might be.

This can be

a moment

of insight.

For convenience

we may wish to

create a concept

to represent such clusterings.

Concepts, Categories and Aristotle

It was Aristotle's great contribution

to create rock logic.

This was done by

forming the idea of 'categories'.

These

could be clearly defined.

For example

there might be a category (or concept)

of a 'dog'.

When you encountered an animal

you would judge

whether

it belonged in that category

or not.

If it did belong

then we might say or think,

'This is a dog.'

Once we had made that judgement

then we could ascribe

all the characteristics of the dog category

to the creature.

For example

we might expect the creature

to bark

and behave like a dog.

Since

'this is a dog'

and 'this is not a dog'

could not both be right

we got the principle of contradiction

which is the basis of the logic.

There is nothing wrong with

concepts and categories

as exploratory devices.

It is when

they are used for

the rigid arguments of rock logic

that there

may be trouble.

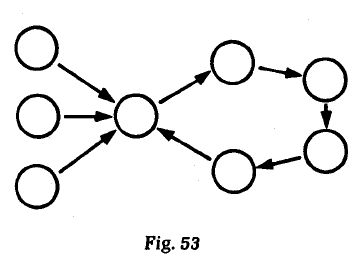

Using water logic or flow notation,

the benefits of having

concepts and categories

are shown in fig. 53.

Here

we can see

how the different attributes

feed into

the collector point

of the concept.

From the concept

we then get

a loop

consisting of

all the fixed characteristics

of that concept.

It is fairly easy

to see

that the whole thing

is either

a guessing game

or circular.

If a creature

has all the attributes

of a dog

then we can call it a dog,

but doing so

will not provide anything

we do not know already.

If the creature

has only some of the attributes

then we can call it a dog

and it will now get the rest of the attributes.

This is a guessing game

because

we assume that a creature cannot have some of the attributes of a dog

and not the others —

just as a duckbilled platypus

has a bill like a duck

but has fur and four legs.

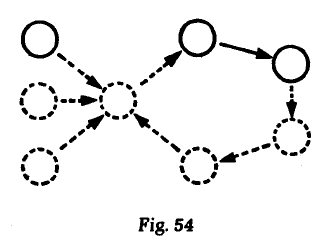

In practice

the process

is more as shown in fig. 54.

Here

the hints or clues

suggest

a hypothesis or guess.

This guess

is then checked out

by looking for

vital features.

If the check is passed

then the

concept description can be applied.

Lumping and Splitting

Science has always been a matter of

lumping together

into a single concept

things

which may seem different,

and separating

into two concepts

things

which seem the same.

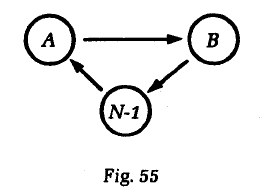

Fig. 55 shows

part of a flowscape

in which two collector points

are linked together

by a single name, N-1.

A scientist

now spots a vital

X factor.

One of the groups

has this X factor

and the other does not.

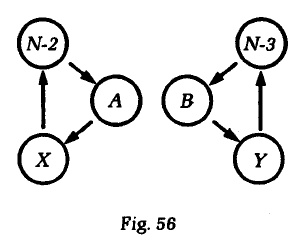

The flowscape

now splits into two,

as shown in fig. 56,

and this split is stabilized

by two new names, N-2 and N-3.

This process

of increased discrimination

happens all the time.

That is how different diseases

get identified

so that treatment

can be more specific.

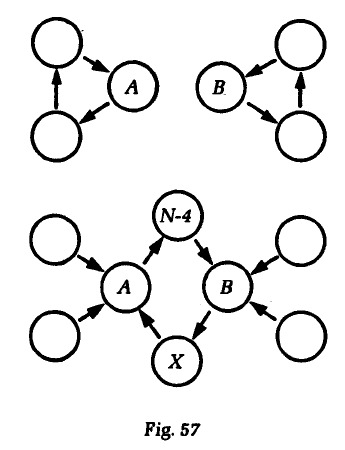

The same process

can happen in reverse.

In Australia

there is a wealth

of brightly colored

parrots, parakeets, lorikeets etc.

Amongst all these

there is one bird

which is almost completely red

and another which is almost completely green.

For a long time

these were considered to be

two different species.

Then it was realized

that they were just

the male and female

of the same species.

This process of lumping is shown in fig. 57.

Two separate groupings

are united by a common feature

and the grouping is stabilized

with a new name N-4,

though it could retain one of the old names.

Concepts and Flexibility

There was a classic experiment

in which students were given

some electrical components

and asked to

make up a circuit

to ring a bell.

There was not

quite enough wire given

to complete the circuit.

Most students

gave up

and declared

that it was impossible.

A few

made use of the metal shaft

of the supplied screwdriver

to complete the circuit.

The majority of students

looked for

a 'piece of wire'.

The exceptional students

worked at a concept level

and looked for a 'piece of metal'.

The ability

to work at a concept level

is crucial for creativity

and for thinking in general.

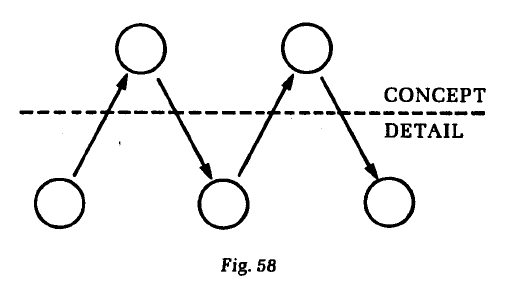

As shown in fig. 58,

we need to keep moving constantly

from the actual detail level

to the concept level

and back again.

This is how

we move

from idea to idea.

This is the basis of

constructive thinking,

for otherwise

we are limited to experience

and what is before us at the moment.

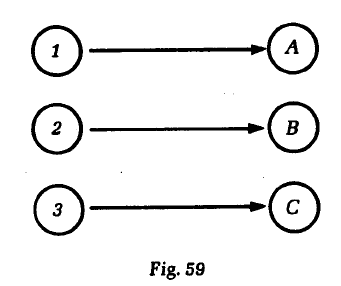

Fig. 59 is an illustration of training.

You can train someone

to react to situation A with response 1,

to situation B with response 2,

and to situation C with response 3.

The training is effective

and these trained people

know what to do.

But if, one day,

situation A occurs

and response 1

is not possible

then that person will be lost.

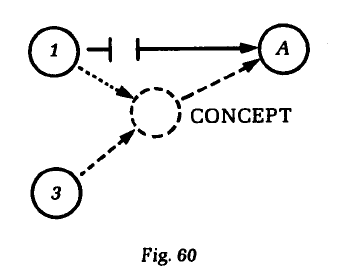

But if the people

had been trained

using a function concept

to link

situation

and reaction

then that person

might have

looked around

and found

that another response

might also carry out that function concept, as shown in fig. 60.

That is why

it might be limiting

to accelerate

the learning of young children.

They can be taught responses

but may lose out

on the development of concepts.

Pre-Concepts and Post-Concepts

Most concepts

are convenient package descriptions

after we know what is in the package.

The legal paragraph

used at the beginning of the section

defines the relevant properties precisely.

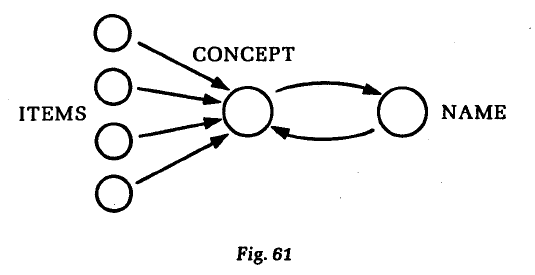

I call these

post-concepts

because they occur

after the event.

This packaging

for the sake of convenience

is shown in fig. 61,

which also indicates

how the concept is stabilized

by a name.

Sometimes,

however,

we start at exactly

the opposite end.

We know

what the concept should do

but we do not know

what the concept is.

Any writer knows this well,

as he or she searches

for just the right word

to describe

a complex set of features.

An engineer might say:

'At this point

we need something

that is going to change shape

and to form a shape

we have predetermined.'

The engineer knows

the features

of what is wanted.

The answer

could be a type of memory metal

which reverts back to a previous shape

at a given temperature.

Such metals are now in use.

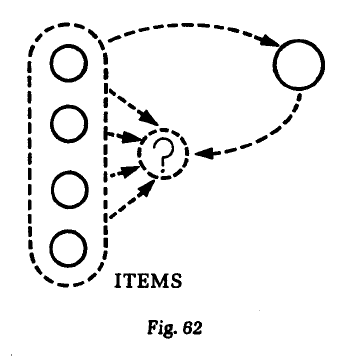

The process is illustrated in fig. 62.

A pre-concept

is like defining a hole

and then looking for something

to fit that hole.

In a post-concept

we find the characteristics together

and name this cluster a concept.

In a pre-concept

we put together the characteristics

and then look around

for something to fit the defined need.

This is an important part

of problem solving.

A pre-concept

is a bit like a hypothesis

since it allows us to

move ahead of where we are at the moment.

I sometimes distinguish between

three types of question.

In a 'shooting question'

we know what we are aiming at

and the answer is 'yes' or 'no'.

This is a checking-out question.

In a 'fishing question'

we bait the hook

and wait to see what turns up.

This is an open-ended search for more information.

In a 'trapping question'

we prepare the trap

to suit

what we want to catch.

This is exactly the same as a pre-concept.

We define the needs

and then look for a way

of satisfying those needs.

Blurry Concepts

In most of our thinking

we are encouraged

to be precise.

This is very much

the nature of

rock logic.

In water logic,

however, the concern

is for movement:

where do we flow to?

There are times when

a blurry or vague concept

is actually more use

than a precise concept.

A blurry concept

can act as

a better collector point

and therefore

a better connector point.

Which is the more useful

of the following two statements?

'I need a match to light this fire'

or, 'I need "some way" of lighting this fire.'

In the first case

you look specifically

for a match

and if you do not find a match

you are blocked.

In the second case

your search

is much broader.

You might use a lighter,

you might take a light from a gas pilot light,

you might generate a spark,

and so on.

In an earlier book of mine

(Practical Thinking, London: Penguin, 1971),

I wrote about 'porridge words'

and the value of blurry concepts.

A precise concept

may fix where we are.

A blurry concept

allows us to move forward.

Once again,

this is partly related to the 'fuzzy logic'

that is now so fashionable

in the computer world.

Precision

often

locks us into the past,

what 'is'

and what has been.

Blurry concepts

open up

the future,

movement

and what might be.

A blurry concept

is not the same as

sloppy thinking.

A blurry concept

is definite

in its own way.

Working Backwards and the Concept Fan

One way to solve problems

is to work backwards.

This is not so easy to do

if we do not know

the solution to the problem.

If you want to reach point P

you can work backwards from that point

but if you are not sure where point P might be,

that is not easy.

There is, however,

a way of working backwards

that I have called.

The Concept Fan.

This is described

in more detail

in Serious Creativity

(New York and London: Harper Collins, 1992)

but I shall also mention it here

since it really depends on

the flow of water logic.

Suppose the purpose of our thinking

is to tackle the problem of

'Traffic congestion in cities'.

From that defined purpose

we work backwards.

What broad concepts

might help us

with that problem?

We might reduce the traffic load.

We might improve flow on the existing road system.

We might increase the available road surface.

Each of these

are broad concepts —

there may be more.

How might we

feed these

broad concepts?

This is the same notion

as the

feeding

of a collector point.

How might we reduce traffic?

We could encourage the use of vehicles with more people on board.

We could discourage drivers from coming into the city.

We could reduce the need for people to come into the city.

Again there will be other concepts which feed the broad concept of reducing traffic.

We would do the same

for each of the other

broad concepts.

Next

we see how

we could

feed these concepts.

In practice this means seeing how the concepts could be put into practical operation.

For example, how might we get vehicles with more people on board?

By

encouraging the use of public transport and making this better,

encouraging car pools and sharing, giving privilege lanes to vehicles with several occupants,

or by restricting central parking.

We do the same for each concept.

How might we

discourage drivers

from driving into the city?

By

charging a special fee for entrance before ten in the morning (as in Singapore),

making no provision for parking and using tough measures for illegal parking,

publicizing pollution levels in the city,

or by publicizing the actual rate of car movement in the city.

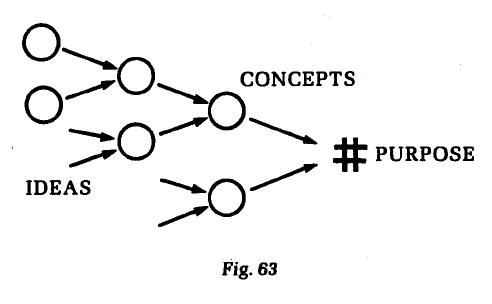

The process is shown schematically in fig. 63.

At the left-hand side

we end up with a number of practical ideas

which feed into the concepts,

which in turn feed into the broad concepts,

which in turn help with the problem.

The interesting point is

that our search is moving backwards

from the purpose (going from the right-hand side to the left-hand side)

but the flow path of achievement is flowing from the left-hand side to the right-hand side.

The process can be very powerful

if you are good

at putting down the different concepts.

This requires some practice.

The concept fan

is not an analysis of the situation

but an elaborated flowscape.

At times you may reach

a pre-concept

or a defined need

but not have a way of doing it.

For example, you might seek

to discourage drivers

by

'damaging their cars'.

Is it possible to find a way of doing this which would be effective but also acceptable?

Possibly not.

Concepts and Flow

This section of the book is important because

concepts

are a very important part of

flow

and water logic.

Concepts are collector points or junctions.

Concepts allow

things to come together.

Concepts allow

us to move across

from idea to idea.

Concepts allow

us to describe things

but also

to search for things (pre-concepts).

The better

you become

at using concepts

the better you will be

at water logic.

The question is always,

'Where does this take us?'

rather than, 'What is this?'

Context, Conditions and Circumstances

In water logic context is hugely important.

I have often used the landscape or river valley analogy to illustrate the flow patterns that form in the self-organizing information system we call the brain.

This analogy gives a good picture but has one major defect.

The landscape is fixed and permanent.

But in the brain

a change of context

can change the landscape.

It is as if

a different landscape

were being observed.

Under one context or set of circumstances

in the brain,

state A will be

succeeded by

(or flow to) state B.

But if the context changes

then A

will flow to C.

The context change

might be chemical.

A change in the chemicals

bathing the nerve cells (or released at nerve endings)

will lead to different sensitivities.

This is also explained in more detail

in the book I am Right - You are Wrong.

It seems likely

that changes in emotion

change

the biochemical balance

and so the flow patterns shift.

This is an essential part of the functioning of the brain

and not some ancient irrelevance.

Self-organizing patterning systems

need

emotions

in order to function well.

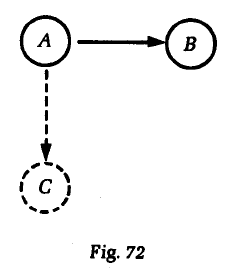

Fig. 72 shows a simple flow from A to B. With a context change the flow is from A to C.

Other inputs into the brain

at the same time

will also alter the context

because

different nerve groupings will be activated

or partially activated (sub-threshold).

So

when the currently activated grouping (or state) tires,

then a different new grouping will follow.

For this reason

the basic water logic theorem

is stated as follows:

'Under conditions X,

state A will always

flow to state B.'

We can return briefly to the jellyfish.

Let us suppose

that at night

they disengage their stings

and sting another jellyfish.

There will therefore be

two arrangements:

the day arrangement

and the night arrangement.

The brain

behaves in the same way

but at a more complex level

because there are many possible contexts.

In an argument

people with opposing perceptions

are often both right.

Each of the opposing perceptions

is based on

a particular set of

circumstances and context.

The variability

may arise

in many ways.

Each party

is looking at

a different part

of the situation.

Each party

is looking at the same situation

but from a different point of view

(like different views of the same building).

The emotional setting is different.

Personal history and backgrounds are different.

Traditions and cultural backgrounds are different.

Immediate past history has created a different context for each of the parties.

It is characteristic of rock logic to ignore all this and to assume that the absolutes of 'truth' are independent of the current context.

Science only works because in any experiment it is assumed that the context is held constant while one factor (the experimental variable) is altered.

In some of the flowscape examples

I have mentioned

the huge importance

of context

and in one example

shown the effect of

a context change.

For most of the examples,

however,

it has been assumed

that the context is fixed.

Is this reasonable?

The flowscape method

deals with

the inner world of perception.

A flowscape

is not a description

of the outer world.

Whenever a flowscape is constructed

the person

laying out the stream of consciousness list

and making the flow connexions

has some definite context in mind

at that moment.

So for that moment

the context is fixed.

If that person

wishes deliberately

to change the context

then a different flowscape

can be laid out.

At a different time

a new flowscape

might be made

and might differ

from the original one

because the context is different.

For this reason

we do not put into a flowscape

the possibility that

state A can also flow to state C

under different circumstances.

That would not only be confusing

but would be incorrect

since it would

refer to a possible perception,

whereas flowscapes

are about actual perceptions

at this moment.

At the intervention stage

it is now possible

to speculate

on how perceptions might be changed

if a context

were to be changed.

Now we are

looking at possibilities.

It is always best

to construct a new flowscape

(or part of the flowscape)

rather than to attempt

to show the change

on the same flowscape.

This causes confusion

because you can always

add a new flow arrow

but you cannot remove an existing one.

The use of different colors is a help

but it is far better

to lay out a new flowscape

for the new context.

What about 'if' factors?

'If he were rich this would happen … but if he were poor then this would happen …'

'If the sun were shining then I would do this … if the sun were not shining I would do that …'

When you take a picture with a camera

the photograph tells you

what is there at that moment.

The photograph does not tell you what it would be like

'if' the sun were to come out,

if the man were thinner,

if the boy were to smile,

if the woman wore a green dress, etc.

In the same way

the flowscape is

a 'picture' of perception

at any one moment.

Where there is an interest in

an 'if' or possible context change

then do another flowscape

for that other context.

Creating Contexts

Quite often there are specific context conditions:

war conditions,

the context of intense jealousy,

if the sun is shining,

if he is rich,

etc.

These are definable contexts.

Most of the time, however, a context is not defined but is built up of many different factors:

experience,

prejudice,

culture,

the media,

etc.

At the beginning of the book I mentioned that one characteristic of water is that you could add water to water and still get just water — in contrast to adding rock to rock.

So we can build up contexts in layers.

We add further inputs one after the other.

The inputs do not have to be connected.

The inputs may be contradictory.

We just add them.

Gradually a context builds up.

Poetry and much of art is concerned with the build up of a mood, scene or understanding in this way.

There is no attempt to interconnect the elements or to make deductions: the mood just develops.

In the creative process,

people are often asked

to saturate their minds with information

and considerations about the subject

and then to let these settle down on their own.

In the book I am Right - You are Wrong the process is formalized as a 'stratal'.

This is different layers or strata which have no connection other than that they are about the same subject and are put down in the same place.

The result is very similar to blank verse or even a Japanese haiku.

There is no conclusion and there is no intention to make any point.

All this is sensible and reasonable behavior in a self-organizing system.

The inputs do organize themselves

to give an output

which we might call intuition.

More importantly

we build up a background context

in which our thinking

can take place.

In setting out to create a flowscape

it can be worthwhile

to establish the context in this way:

putting down layers of

statements and considerations.

This creates the context

in which the flowscape

is going to be set.

From this

also comes

the stream of consciousness list of points.

This preliminary stage

is a sort of sensitizing

of the mind

to the subject.

Accuracy and Value

If flow and water logic

are so heavily dependent on context

and if context can be so variable,

then how can a flowscape

ever

be accurate

or have a value?

Our actions

arise from our perceptions

and we do manage to

initiate and carry through sensible actions.

Perceptions are changeable

but are also stable enough

to give us

actions and flowscapes.

If I asked you to

arrange the numbers 3 5 2 4 1 6 from the smallest to the biggest,

you would have little difficulty in putting down 1 2 3 4 5 6.

If I asked you to

arrange the numbers 2 13 8 20 3 9 from the smallest to the biggest,

you would not tell me that it is impossible because all the numbers are not there.

You would arrange them quite simply: 2 3 8 9 13 20.

In the same way

a flowscape

does not have to be comprehensive

to have value.

We arrange

what we have

and then see what we get

'Accuracy' is a term which comes directly from rock logic.

Is the flowscape

an accurate reflection

of the perception of the person

making the flowscape?

If it is made honestly

then it will be a reflection

of that person's perception —

because it is made with perception.

If the person puts down

what he or she 'thinks they ought to think'

then that is the picture that will emerge.

The value of a flowscape

is that it allows us to

look at

our perceptions.

We can

agree with them

or disagree with them.

We may get

insights

and also a sense of relative importance

and controlling factors.

We may observe

how the perceptions might be changed.

We may get ideas or approaches

for acting in the outer world

represented by the flowscape

of the inner world.

All these things are values.

Could we end up fooling ourselves?

The answer is certainly 'yes' because we are very good at that.

But we have a much better chance of detecting the self-deception with a flowscape than without it.

Flowscapes do not have

a 'proving value' as in rock logic.

Their value is illustrative and suggestive.

A flowscape provides

a framework

or hypothesis

for looking at the world.

A flowscape provides a tangible way of getting to work on our perceptions.

Do not set out to construct the 'correct' flowscape.

Put down the stream of consciousness list

and then work forward from that

and see what emerges.

Then look at that.

Attention Flow

Related: How to Be More Interesting

You are walking through long grass and suddenly you hear a rustle right behind you.

Your attention switches to that rustle.

You are examining a piece of jewelry and the assistant puts another piece in front of you.

Your attention switches to the new piece.

You are talking to someone at a cocktail party and suddenly one of her earrings falls off.

Your attention switches to that.

It is hardly surprising that

if something new turns up

your attention may be caught by that.

But what about those situations where there is nothing new?

How then

does attention

shift or flow?

You can live in a house for years and not notice some feature until a guest points it out.

The Boy Scouts have a game, called, I believe, Kim's Game, in which you are presented with a tray of objects which is then removed after a few moments.

You try to recall as many objects as you can.

Noticing things is certainly not easy and may require a lot of training.

Medical students are taught to notice all sorts of features of a patient in order to help with the diagnosis.

Conan Doyle applied his medical training in this respect to the behavior of his detective character, Sherlock Holmes.

There is a sort of paradox in that

the mind is

extremely good at recognizing things

and yet poor at noticing things.

From a tiny fraction of a familiar picture someone will recognize the picture.

From a single bar someone will recognize a musical piece.

Perhaps there is no paradox at all.

We notice the familiar things we are prepared to notice.

At the same time very unusual things will catch our attention.

Anything in between is unlikely to be noticed.

This is not at all a bad design for a living creature to make its way through life.

In many amusement parks today there are long water chutes in which a little water running down a chute provides enough slipperiness for a child to slide down the entire chute.

The surface has to be very smooth.

Imagine the trouble that would be caused by a protruding bolt.

There is the same effect when something interferes with the smooth flow of attention.

The opposite of interruption is the smooth flow that contributes to aesthetics.

In a way art is a choreography of attention,

leading attention first here

and then there.

The same is true of the art of a good storyteller.

There is

background

and foreground

and loops of attention.

You look at a beautiful Georgian house set amongst trees.

At first you look at the whole setting.

Then your attention moves to the house itself.

Then to the portico or main door.

Then back to the house.

Then to an individual window.

It is this dance of attention that gives us the feeling of pleasure.

It is probably true that there are

certain things

that the human mind

finds intrinsically attractive.

There are certain proportions

which may or may not

reflect the proportions

of a mother's face

to an infant.

There are certain rhythms

which may or may not be

related to the effect

of the mother's heartbeat

upon a child.

The rest may be

the rhythm of

the flow of attention.

In a sense

all art

is a sort of music.

We often think of attention

as a person holding a torch

and directing the beam

at one thing after another.

This does happen sometimes.

If you attend very formal art appreciation classes

you may be given

a sort of check-list of attention.

Notice the use of light and shade.

Notice the disposition of the figures.

Notice the use of color.

Notice the brushwork.

Notice the faces, etc.

Here, attention is flowing along a preset pattern

in order to

notice things in the world in front.

Mostly, however, there are no check-lists

except those

set by familiarity and expectation.

Mostly attention flows

according to

the rules of water logic.

If the flow of attention

turns up something interesting

then there is a new direction,

and new loops form.

You might be looking

at the carving on a Hindu temple

and suddenly notice a swastika sign.

Because of the association of

the swastika with Nazi Germany

your attention is caught

and loops around in that area.

You may wonder

what the sign is doing there

if you do not know

that it is indeed

an ancient Hindu symbol.

So the attention flow itself

can turn up things

which develop

further attention flows.

Drucker and de Bono topics

You are looking at something in a museum

and then you read the label —

this prompts you to notice things

you have not noticed.

So even if

there are no new events,

attention can turn up 'new events'.

If attention follows the rules of water logic

then why does attention

not lock itself

into a stable pattern

and stay there?

To some extent

this is what attention

normally does.

Most of the time

we recognize things

and do not give them a second glance,

precisely because

we have locked into

the usual stable pattern.

At other times

the flow of attention

uncovers new things

which then

develop new loops.

Any new input

will change the context

and so

get us out of a stabilized loop.

Attention flow

may uncover

areas of

richness

and detail.

The immense richness

of the carvings on a Hindu temple

makes it difficult for us to see it

as a whole.

In contrast, the attention flow of the Taj Mahal

is an excellent example of

a smooth flow

from the whole

to a part

and back to the whole

and back to another part,

and so on.

If there is too much detail

we get bogged down.

If there is too little detail

we can only see the whole,

and attention does not flow —

as in some modern buildings.

Somewhere between

too much and too little detail

is the richness of the Gothic style.

This is more like

the intricacies of a morris dance

rather than the waltz of the classical style,

although that could also have

many intricacies.

The difference between

perception which is purely internal

and attention flow which is directed outwards

is that attention

can trigger new perceptions.

This can also happen in

the inner world of reflective perception

but is much more rare.

In general, in reflective perception,

it is a matter of existing perceptions

which organize themselves into flow patterns

which we attempt to capture with flowscapes.

If a dog is taken on a walk

then the dog will

stop,

sniff around

and explore one area

then set off for another area,

which is then explored again, and so on.

Attention flow is somewhat like that.

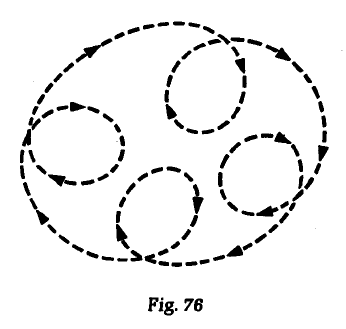

Fig. 76 shows that the overall track of attention flow is really made up of several exploratory loops on the way.

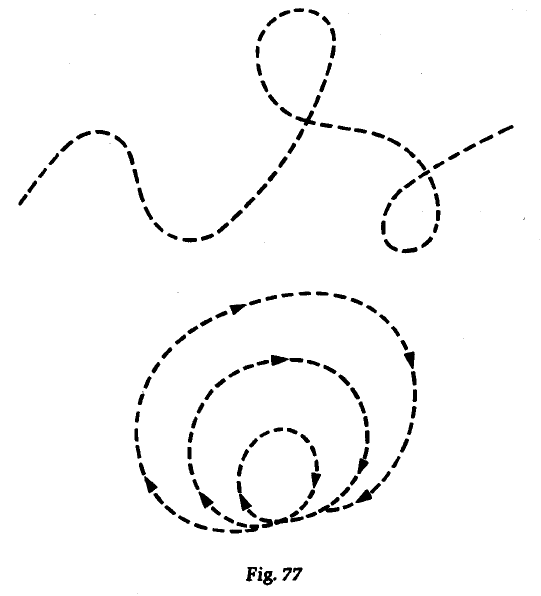

If we include the loops

in the overall track

then fig. 77

shows some possible

attention-flow tracks.

In one case

the track just wanders about.

In another case

the track keeps coming back

to the starting point

but then moves out

in widening circles,

all of which still come back to the start.

In another case

the loops succeed each other

but the whole returns full circle

to the starting point.

I suspect

the attention flows

that complete the circles

are the ones

which we would

find most appealing.

'Isness'

Indian philosophies put a lot of emphasis on 'isness'

which means

really seeing

what something 'is'.

If you sit and contemplate a rose for three hours

you will begin to see a 'rose'.

Mostly attention has a practical job to do:

explore a matter

until you

recognize it

and then move on.

Once the perceptual loop

has stabilized

we move on.

So we do not really see a rose

but just the usual impression

of a rose.

Meditation is an attempt

to halt the flow of attention

and to unravel

the stable perceptual loops.

One can ascribe metaphysical value to that

as you wish.

A somewhat similar effect

can be obtained with drugs

that interfere with

the normal nerve coordination,

so making familiar things look strange

because the established flow patterns

no longer work.

Tension

Salvador Dali's famous painting

of the melting watch

is a pure example of

the use of the tension

between two opposing patterns:

the rigidity of a watch

that is necessary for it to perform

its function of accuracy,

and the soft contours of wax-like melting.

The mixing,

opposing

and juxtaposing of images

has an extensive tradition in art.

It is unusual,

it catches our attention

and makes us stop,

think

and perceive anew.

Without claiming that it is easy to do this well,

it can be said

that this is a relatively simple technique

used also by bad artists

and bad poets

to achieve effect.

To talk about the 'cold fire of his spirit'

creates a perceptual tension

between

the normal perception of fire as hot

and the attachment of the image of 'cold'.

The mind does not quite know how to

settle down

and oscillates

between the two images,

creating an effect

more powerful than

'the fire of his spirit'.

There is genuine descriptive value

in that the 'cold fire'

does suggest

a passion that is

cold,

calculating

and ruthless.

A significant part of art

is based on

the need

to unsettle the usual.

Normally

attention does its work

and moves on.

Attention flow

is normally dismissive.

Art

seeks

to highlight,

to deepen perception

and to open up insights.

This is done

by disrupting patterns,

by juxtaposing patterns,

by providing new pattern frameworks.

If attention were a cook

it would always

contentedly cook

the same dishes.

By

interfering with the cooking,

by providing new ingredients,

by removing staple ingredients,

art sets out to

re-excite our taste buds

with new dishes

that allow us to

taste the old ingredients anew.

When the Impressionists

first started

to show their work

it was judged

hideous and ugly

by most of the

art critics and connoisseurs.

This was because it was 'ugly'

when viewed through

the frames of expectation

of existing and traditional painting.

People had to be trained

to look at the paintings

in a different way

to appreciate their beauty.

Carrying this to an extreme,

if you put a pile of bricks

into an art gallery

and you ask people

to look at the bricks

as a work of art

then they really do become a work of art.

This circles back to

the 'isness' I mentioned before.

Our normal perception patterns

treat bricks as mundane building materials

but if we break that loop

we see them differently

but still keep a faint echo

of their constructive value.

Triggering

A finger on a trigger

can release

a child's pop gun

or a nuclear bomb.

There is no direct relationship

between

the pressure on the trigger

and the effect.

A system is set 'to go'

and you trigger it to go.

Perception

has already set up

the patterns

which are ready to go.

The triggers or stimulation

we receive

from the world around

set off flow patterns

in the brain

which settle down

into the standard perception.

It is something like

those children's play books

in which the child

is asked

to join up the given dots.

The patterns

that we operate as perception

depend upon the triggers received,

past experience

and the organizing behavior of the brain.

It is this organizing behavior

that has been the subject

of this book.

This behavior involves

the formation of

temporarily stable states

which tire

and are succeeded by

other similar states

in the flow of water logic.

This flow itself

stabilizes as a loop

and that forms

the standard perception.

Attention flow

is determined by

the outer world

and also by the standard perception patterns

which direct where we should look

in order to check out

the suitability of the patterns.

It is very similar to a conversation.

In a conversation

you listen to what is being said

but your own mind

is going about its own business.

So we pay attention

to what is out there

but our own brain is busy

with its perception patterns and flows.

Just as the leaves of a tree

all 'flow' down the branches

into the tree trunk

so the different sensations

are 'drained' into

an established flow pattern.

Directing Attention

Attention flow

is determined by

what is out there,

our standard perceptual patterns,

the context of the moment

and

what we may be trying to do.

Is this natural flow of attention

the most beneficial or effective?

It may be effective for

long-term survival of the species:

do not waste energy on

what you already know

and what is not valuable at the moment.

But it is less than effective for other matters.

The whole purpose of a university education

is supposed to be to train the mind

to probe more deeply —

and this requires

attention-directing practice.

The formal checklist

for art appreciation

that I gave earlier

is a simple example

of attention directing.

It may seem rigid and mechanical

but in time

it does result in

better attention flows.

The very first lesson

in the CoRT thinking program for teaching thinking as a school subject

has a simple attention-directing device called

the PMI.

The student directs his or her attention to

the Plus aspects of the situation,

then the Minus aspects

and finally the Interesting aspects.

If people do this anyway,

as some claim,

then the exercise

should make no difference.

Instead

we get huge differences

in final judgement

(from 30 out of 30 students being in favor of an idea to only one being in favor).

There is no mystery.

The normal attention flow results in

an immediate emotional reaction

which then determines an attention flow

to support that reaction.

The PMI ensures

a basic exploration of the subject

before judgement.

This is not at all natural.

What is natural is to

interpret,

recognize

and judge

as quickly as possible.

That has long-term survival value.

The flowscapes

put forward in this book

are attention-directing devices

in the sense that

the examination of a flowscape

can direct our attention

to the significant parts

of our own perception.

Errors

Can there be misleading errors in a flowscape?

Since a flowscape does not claim to be right it is difficult for it to be wrong.

A flowscape is a hypothesis or a suggestion.

It is a provisional way of looking at the shape of our perceptions.

If we do not like what we see

then we can check out

what it is that we do not like.

When we get a surprise,

we may find it is the surprise of insight:

'I did not realize that point was as central as it is.'

Since most of the attention

is on

collector points and stable loops,

there is a danger

that an important point

which just happens to feed into a collector point

will not get the attention it deserves.

In a way this is

as it should be

because collector points and loops

do dominate perception.

We usually believe that

important points

should dominate perception

but very often

they do not.

A flowscape

is a picture of perception

as it is,

not as it should be

There is a danger

of constructing a false flowscape,

which is one

which is carefully contrived

to give you the perception

you think you ought to have.

In such cases

you are cheating no one

but yourself.

There is no limit

to the number of flowscapes

you can lay out

on any subject.

You may

vary the connexions

and make another flowscape.

You can alter

some of the items

on the base list

and make a further flowscape.

Examine them all

and see

what you can get

from them.

When you attempt to

make flowscapes

for other people

you may be totally in error.

You have to keep that in mind.

Your perception

of another person's perception

may leave out something vital.