An introduction to Peter Drucker—the towering management thought leader

The center of modern society is the managed institution.

The managed institution is society’s way of getting things done these days.

And management is the specific tool, the specific function, the specific instrument, to make institutions capable of producing results (on the outside).

The institution, in short, does not simply exist within and react to society.

It exists to produce results on and in society.

… snip, snip …

Management’s concern and management’s responsibility are everything that affects the performance of the institution and its results—whether inside or outside, whether under the institution’s control or totally beyond it.

... snip, snip ...

All managers do the same things whatever ... their organization.

All of them have to bring people—each of them possessing a different knowledge—together for joint performance.

All of them have to make human strengths productive in performance and human weaknesses irrelevant.

... snip, snip ...

Peter Drucker was far more and far different from a limited subject specialist. His thought-scape was at least the human ecology evolving in time which includes all subjects and their integration across time. See social ecologist below.

Remembering Peter Drucker from the November 2009 issue of The Economist.

Everybody needs a coach and he’s as good as it gets.

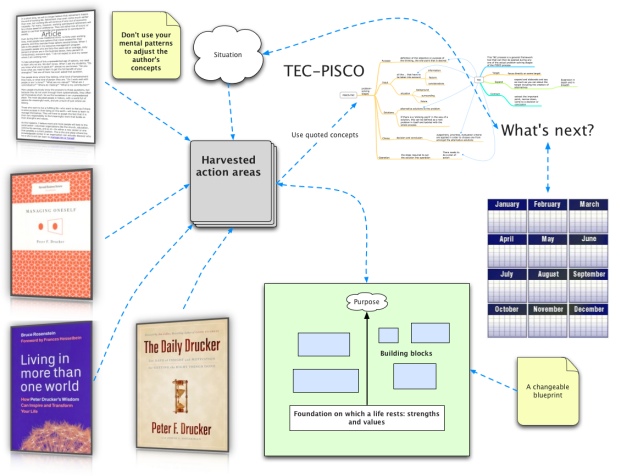

See Drucker’s life as a knowledge worker and Peter’s Principles for quick samples of his wisdom and insight—these contain crucial ideas for one’s radar.

Caution: Don’t take other people’s word for what Peter Drucker said, wrote, or thought—they have their own agenda, own viewpoint, own history, and own mental patterns. They often quote him out of context to prove a self-serving point.

If you want the benefit of his wisdom, read him for yourself; take structured notes; convert those notes into daily action; revisit the original text and your notes; revise your action plan; and go to work. Repeat (long) before you think you need to. See concepts to daily action and conceptual resource digestion for a process overview.

Career and Life Guidance from Peter Drucker

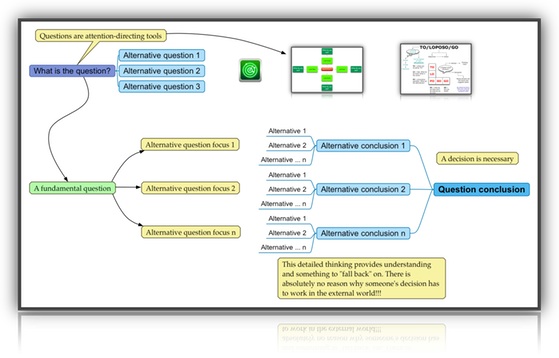

is attention-directing work

His work is part of a foundation for future directed decisions. Try to look for the long-term value in his concepts and ideas.

About Peter F. Drucker

From the Foreword to The Daily Drucker by Jim Collins

… Drucker’s primary contribution is not a single idea, but rather an entire body of work that has one gigantic advantage: nearly all of it is essentially right.

Drucker has an uncanny ability to develop insights about the workings of the social world, and to later be proved right by history.

His first book, The End of Economic Man, published in 1939, sought to explain the origins of totalitarianism; after the fall of France in 1940, Winston Churchill made it a required part of the book kit issued to every graduate of the British Officer’s Candidate School.

His 1946 book The Concept of the Corporation analyzed the technocratic corporation, based upon an in-depth look at General Motors.

It so rattled senior management in its accurate foreshadowing of future challenges to the corporate state that it was essentially banned at GM during the Sloan era.

Drucker’s 1964 book was so far ahead of its time in laying out the principles of corporate strategy that his publisher convinced him to abandon the title Business Strategies in favor of Managing for Results, because the term “strategy” was utterly foreign to the language of business.

There are two ways to change the world: with the pen (the use of ideas) and with the sword (the use of power).

Drucker chooses the pen, and has rewired the brains of thousands who carry the sword.

When in 1956 David Packard sat down to type out the objectives for the Hewlett-Packard Company, he’d been shaped by Drucker’s writings, and very likely used The Practice of Management—which still stands as perhaps the most important management book ever written—as his guide.

In our research for the book Built to Last, Jerry Porras and I came across a number of great companies whose leaders had been shaped by Drucker’s writings, including Merck, Procter & Gamble, Ford, General Electric, and Motorola.

Multiply this impact across thousands of organizations of all types—from police departments to symphony orchestras to government agencies and business corporations—and it is hard to escape the conclusion that Drucker is one of the most influential individuals of the twentieth century.

Druckerisms — consider how you might calendarize them

“Economists never know anything until twenty years later. There are no slower learners than economists. There is no greater obstacle to learning than to be the prisoner of totally invalid but dogmatic theories. The economists are where the theologians were in 1300: prematurely dogmatic” — Frontiers of Management

“The customer never buys what you think you sell. And you don’t know it. That’s why it’s so difficult to differentiate yourself.”

“People in any organization are always attached to the obsolete—the things that should have worked but did not, the things that once were productive and no longer are.” ―

Follow effective action with quiet reflection. From the quiet reflection will come even more effective action.

Knowledge has to be improved, challenged, and increased constantly, or it vanishes.

Management by objective works – if you know the objectives. Ninety percent of the time you dont.

Objectives are not fate; they are direction. They are not commands; they are commitments. They do not determine the future; they are means to mobilize the resources and energies of the business for the making of the future.

Most discussions of decision-making assume that only senior executives make decisions or that only senior executives decisions matter. This is a dangerous mistake.

People who don’t take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year. People who do take risks generally make about two big mistakes a year.

Plans are only good intentions unless they immediately degenerate into hard work.

The aim of marketing is to know and understand the customer so well the product or service fits him and sells itself.

The purpose of a business is to create and keep customers.

There is nothing so useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all.

The only thing we know about the future is that it will be different.

Efficiency is doing better what is already being done.

The productivity of work is not the responsibility of the worker but of the manager.

No institution can possibly survive if it needs geniuses or supermen to manage it. It must be organized in such a way as to be able to get along under a leadership composed of average human beings.

The most important thing in communication is to hear what isn’t being said.

Rank does not confer privilege or give power. It imposes responsibility.

Effective leadership is not about making speeches or being liked; leadership is defined by results not attributes.

All one has to do is to learn to say ‘no’ if an activity contributes nothing.

What is the first duty — and the continuing responsibility — of the business manager? To strive for the best possible economic results from the resources currently employed or available.

People do not know that you cannot successfully innovate in an existing organization unless you systematically abandon. As long as you eliminate, you’ll eat again. But if you stop eliminating, you don’t last long.

Leaders shouldn’t attach moral significance to their ideas: Do that, and you can’t compromise.

The only things that evolve by themselves in an organization are disorder, friction, and malperformance.

One cannot buy, rent or hire more time. The supply of time is totally inelastic. No matter how high the demand, the supply will not go up. There is no price for it. Time is totally perishable and cannot be stored. Yesterday’s time is gone forever, and will never come back. Time is always in short supply. There is no substitute for time. Everything requires time. All work takes place in, and uses up time. Yet most people take for granted this unique, irreplaceable and necessary resource.

The really important things are said over cocktails and are never done. (calendarize this?)

Doing the right thing is more important than doing the thing right.

Concentration is the key to economic results. No other principles of effectiveness is violated as constantly today as the basic principle of concentration.

Long range planning does not deal with future decisions, but with the future of present decisions.

Leadership is not magnetic personality — that can just as well be a glib tongue. It is not ‘making friends and influencing people’ — that is flattery. Leadership is lifting a person’s vision to high sights, the raising of a person’s performance to a higher standard, the building of a personality beyond its normal limitations.

What gets measured, gets managed.

No decision has been made unless carrying it out in specific steps has become someone’s work assignment and responsibility

Whenever you see a successful business, someone once made a courageous decision.

Meetings are a symptom of bad organization. The fewer meetings the better.

The entrepreneur always searches for change, responds to it, and exploits it as an opportunity.

Company cultures are like country cultures. Never try to change one. Try, instead, to work with what you’ve got.

Any organization develops people: It has no choice. It either helps them grow or stunts them.

Don’t take on things you don’t believe in and that you yourself are not good at. Learn to say no.

If you can’t establish clear career priorities by yourself, use friends and business acquaintances as a sounding board. They will want to help. Ask them to help you determine your ‘first things’ and ‘second things.’ Or seek an outside coach or advisor to help you focus. Because if you don’t know what your ‘first things’ are, you simply can’t do them FIRST.

Teaching is the only major occupation of man for which we have not yet developed tools that make an average person capable of competence and performance. In teaching we rely on the naturals’, the ones who somehow know how to teach.

Don’t travel too much. Organize your travel. It is important that you see people and that you are seen by people maybe once or twice a year. Otherwise, don’t travel. Make them come to see you.

The leaders who work most effectively, it seems to me, never say ‘I’. And that’s not because they have trained themselves not to say ‘I’. They don’t think ‘I’. They think ‘we’; they think ‘team’. They understand their job to be to make the team function. They accept responsibility and don’t sidestep it, but ‘we’ gets the credit… This is what creates trust, what enables you to get the task done.

Too many leaders try to do a little bit of 25 things and get nothing done. They are very popular because they always say yes. But they get nothing done.

Efficiency is doing things right; effectiveness is doing the right things.

The purpose of business is to create and keep a customer.

Again, let’s start out discussing what not to do. Don’t try to be somebody else. By now you have your style. This is how you get things done.

Leaders communicate in the sense that people around them know what they are trying to do. They are purpose driven — yes, mission driven. They know how to establish a mission.

I tell all my clients that it is absolutely imperative that they spend a few weeks each year outside their own business and actively working in the marketplace, or in a university lab in the case of technical people. The best way is for the chief executive officer to take the place of a salesman twice a year for two weeks.

Few top executives can even imagine the hatred, contempt and fury that has been created — not primarily among blue-collar workers who never had an exalted opinion of the ‘bosses’ — but among their middle management and professional people. What do you want to be remembered for?

When you are the chief executive, you’re the prisoner of your organization. The moment you’re in the office, everybody comes to you and wants something, and it is useless to lock the door. They’ll break in. So, you have to get outside the office. But still, that isn’t traveling. That’s being at home or having a secret office elsewhere. When you’re alone, in your secret office, ask the question, ‘What needs to be done?’ Develop your priorities and don’t have more than two. I don’t know anybody who can do three things at the same time and do them well. Do one task at a time or two tasks at a time. That’s it. OK, two works better for most. Most people need the change of pace. But, when you are finished with two jobs or reach the point where it’s futile, make the list again. Don’t go back to priority three. At that point, it’s obsolete.

We suffer from over-choice: 67 varieties of toothpaste, 487 styles of shoes, 186 brands of cell phones with 137 telephone companies. We demand more variety than we could possibly need or want; and as a result, we get lost in options, opportunities, and choices. There are 87 varieties of lawyers, and 75 specialties inside medicine. The world of work can be a confusing landscape.

That people even in well paid jobs choose ever earlier retirement is a severe indictment of our organizations — not just business, but government service, the universities. These people don’t find their jobs interesting.

A critical question for leaders is: ‘When do you stop pouring resources into things that have achieved their purpose?’

Morale in an organization does not mean that ‘people get along together’; the test is performance not conformance.

An employer has no business with a man’s personality. Employment is a specific contract calling for a specific performance… Any attempt to go beyond that is usurpation. It is immoral as well as an illegal intrusion of privacy. It is abuse of power. An employee owes no ‘loyalty,’ he owes no ‘love’ and no ‘attitudes’ — he owes performance and nothing else.

Ideas are somewhat like babies — they are born small, immature, and shapeless. They are promise rather than fulfillment. In the innovative company, executives do not say, ‘This is a damn-fool idea.’ Instead they ask, ‘What would be needed to make this embryonic, half-baked, foolish idea into something that makes sense, that is an opportunity for us?’· Innovation is the specific instrument of entrepreneurship… the act that endows resources with a new capacity to create wealth.

Once a year ask the boss, ‘What do I or my people do that helps you to do your job?’ and ‘What do I or my people do that hampers you?’

Great leaders find out whether they picked the truly important things to do. I’ve seen a great many people who are exceedingly good at execution, but exceedingly poor at picking the important things. They are magnificent at getting the unimportant things done. They have an impressive record of achievement on trivial matters.

How does one display integrity? ‘By asking, especially when taking on office: What is the foremost need of the institution and therefore my first task and duty?’

Ask yourself: What major change in the economy, market or knowledge would enable our company to conduct business the way we really would like to do it, the way we would really obtain economic results?

Ask yourself: What would happen if this were not done at all?

So much of what we call management consists in making it difficult for people to work.

The subordinate’s job is not to reform or re-educate the boss, not to make him conform to what the business schools or the management book say bosses should be like. It is to enable a particular boss to perform as a unique individual.

Effective leaders check their performance. They write down, What do I hope to achieve if I take on this assignment?’ They put away their goals for six months and then come back and check their performance against goals. This way, they find out what they do well and what they do poorly.

The individual is the central, rarest, most precious capital resource of our society

The most efficient way to produce anything is to bring together under one management as many as possible of the activities needed to turn out the product.

The computer is a moron.

Successful leaders make sure that they succeed! They are not afraid of strength in others.

The CEO needs to ask of his associates, ‘What are you focusing on?’ Ask your associates, ‘You put this on top of your priority list — why?’ The reason may be the right one, but it may also be that this associate of yours is a salesman who persuades you that his priorities are correct when they are not.

Free enterprise cannot be justified as being good for business. It can be justified only as being good for society.

Executives owe it to the organization and to their fellow workers not to tolerate nonperforming individuals in important jobs.

A manager is responsible for the application and performance of knowledge.

Accept the fact that we have to treat almost anybody as a volunteer.

Business, that’s easily defined — it’s other people’s money.

Few companies that installed computers to reduce the employment of clerks have realized their expectations… They now need more and more expensive clerks even though they call them ‘operators’ or ‘programmers.

What’s absolutely unforgivable is the financial benefit top management people get for laying off people. There is no excuse for it. No justification. This is morally and socially unforgivable, and we will pay a heavy price for it.

A man should never be appointed into a managerial position if his vision focuses on people’s weaknesses rather than on their strengths.

Start with what is right rather than what is acceptable.

Performing organizations enjoy what they’re doing

Far too many people—especially people with great expertise in one area—are contemptuous of knowledge in other areas …

The formation of character is a lifelong process.

It is … more important to have quit once than to have been fired once.

The greatest sin may be the new 20th-century sin of indifference.

The computer memory is only the mechanical expression of the organizational fact.

Peter F. Drucker—writer, management consultant, and university professor—was born in Vienna, Austria, November 19, 1909 and died in Claremont, California, on November 11, 2005.

After receiving his doctorate in public and international law from Frankfurt University in Frankfurt, Germany, he worked as an economist and journalist in London before moving to the United States in 1937.

Peter Drucker published his first book, The End of Economic Man, in 1939. He joined the faculty of New York University’s Graduate Business School as professor of management in 1950. Since 1971, he had been Clarke Professor of Social Science and Management at the Claremont Graduate University in Claremont, California. The university named its management school after him in 1987.

Peter Drucker wrote thirty-four major books in all: fifteen books deal with management, including the landmark books The Practice of Management and The Effective Executive: sixteen cover society, economics, and politics; two are novels; and one is a collection of autobiographical essays. His most recent book, The Effective Executive in Action, was published in fall 2005.

Peter Drucker also served as a regular columnist for The Wall Street Journal from 1975 to 1995 and contributed essays and articles to numerous publications, including the Harvard Business Review, The Atlantic Monthly, and The Economist. Throughout his sixty-five year career, he consulted with dozens of organizations across the world—ranging from the world’s largest corporations to entrepreneurial start-ups and various government and nonprofit agencies.

Experts in the worlds of business and academia regard Peter Drucker as the founding father of the study of management.

For his accomplishments, Peter Drucker was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush on July 9, 2002. A documentary series about his life and work appeared on CNBC ten times from December 24, 2002, through January 3, 2003.

Above is quoted from Management, Revised Edition

Peter Drucker ::: political / social ecologist

The Über Mentor

Remembering Peter Drucker

(from the November 2009 issue of The Economist)

“To know something,

to really understand something important,

one must look at it from sixteen different angles.

People are perceptually slow,

and there is no shortcut to understanding;

it takes a great deal of time.”

discontinuity ::: the black cylinder experiment and its relevance ::: beyond the numbers

… but the only thing that is “new” about political ecology is the name.

As a subject matter and human concern, it can boast ancient lineage, going back all the way to Herodotus and Thucydides.

It counts among its practitioners such eminent names as de Tocqueville and Walter Bagehot.

Its charter is Aristotle’s famous definition of man as “zoon politikon,” that is, social and political animal.

As Aristotle knew (though many who quote him do not), this implies that society, polity, and economy though man’s creations, are nature to man, who cannot be understood apart from and out of them.

It also implies that society, polity and economy are a genuine environment, a genuine whole, a true “system,” to use the fashionable term, in which everything relates to everything else and in which men, ideas, institutions, and actions must always be seen together in order to be seen at all, let alone to be understood.

Political ecologists are uncomfortable people to have around.

Their very trade makes them defy conventional classifications, whether of politics, of the market place, or of academia.

“Political ecologists” emphasize that every achievement exacts a price and, to the scandal of good “liberals",” talk of “risks” or “trade-offs,” rather than of “progress.”

But they also know that the man-made environment of society, polity, and economics, like the environment of nature itself, knows no balance except dynamic disequilibrium.

Political ecologists therefore emphasize that the way to conserve is purposeful innovation—and that hardly appeals to the “conservative.”

Political ecologists believe that the traditional disciplines define fairly narrow and limited tools rather than meaningful and self-contained areas of knowledge, action, and events—in the same way in which the ecologists of the natural environment know that swamp or the desert is the reality and ornithology, botany, and geology only special-purpose tools.

Political ecologists therefore rarely stay put.

It would be difficult to say, I submit, which of chapters in this volume are “management,” which “government” or “political theory,” which “history” or “economics.”

The task determines the tools to be used: but this has never been the approach of academia.

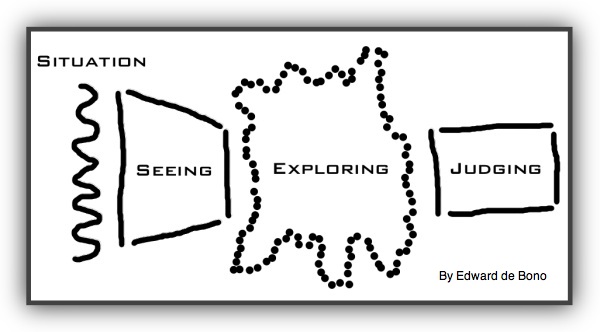

From analysis to perception — the new world view

Form and Function Connections: see chapters

On Being the Right Size and On Being the Wrong Size

in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices and others.

Students of man’s various social dimensions—government, society, economy, institutions—traditionally assume their subject matter to be accessible to full rational understanding.

Indeed, they aim at finding “laws” capable of scientific proof.

Human action, however, they tend to treat as nonrational, that is, as determined by outside forces, such as their “laws.”

The political ecologist, by contrast, assumes that his subject matter is far too complex ever to be fully understood—just as his counterpart, the natural ecologist, assumes this in respect to the natural environment.

But precisely for this reason the political ecologist will demand—like his counterpart in the natural sciences—responsible actions from man and accountability of the individual for the consequences, intended or otherwise, of his actions.

They aim at an understanding of the specific natural environment of man, his “political ecology,” as a prerequisite to effective and responsible action, as an executive, as a policy-maker, as a teacher, and as a citizen.

Not one reader, I am reasonably sure, will agree with every essay; indeed, I expect some readers to disagree with all of them.

by bobembry: Carefully reading his writings is a time-investment — an opportunity to travel a brainroad and create a mental landscape (brainscape).

Having the ability to revisit one of these provides a brainaddress — a way back to a brainscape.

In this case the brainroad is the mental terrain you covered during your reading.

The brainscape is the entire topic landscape.

Creating a brainaddress will take a little thinking.

Your collection of bookmarks is a set of brainaddresses.

Which ones are truly valuable?

Which ones will mean something ten years from now?

But then I long ago learned that the most serious mistakes are not being made as a result of wrong answers.

The truly dangerous thing is asking the wrong questions.

Men, Ideas & Politics

Questions are attention-directing tools

Larger

read more about social ecology

Peter Drucker also viewed himself as a bystander.

Others viewed him: As a Social and Management Theorist; Management Guru; Management Visionary; A man for the ages, as new as tomorrow; The Man Who Invented Management; an Intellectual Giant; Father of management; an organization consultant; political economist and author.

If a young Peter Drucker turned up today at a top-flight business school he would not be considered for an assistant professorship, let alone tenure. The most influential management thinker of the modern era refused to play the academic game.

In the words of Tom Peters: “Drucker effectively by-passed the intellectual establishment. So it’s not surprising that they hated his guts.”

“He makes you think,” Jack Welch, then-chairman of General Electric Co., told the magazine, while Intel co-founder Andrew Grove declared, “Drucker is a hero of mine. He writes and thinks with exquisite clarity—a standout among a bunch of muddled fad mongers.”

“He would never give you an answer. That was frustrating for a while. But while it required a little more brain matter, it was enormously helpful to us. After you spent time with him, you really admired him not only for the quality of his thinking but for his foresight, which was amazing. He was way ahead of the curve on major trends.”

Towering Reputations

Over a period a time, people in the public light acquire a reputation. It is very difficult (almost impossible) to retain an unwarranted towering reputation—too many opportunities for being proven ignorant, stupid, wrong or ineffective.

Tributes to Peter Drucker

After over 30 years of reading from a wide variety of sources only one name emerges as THE master (informed) wisdom source on how the world works or should work.

His work had, has, and will continue to have a global impact on our lives in ways that are probably not obvious or convenient. His thinking is relevant and it matters. His written work is repeatedly useful in helping “look out the windows” onto the world around us and seeing what’s really there plus helping systematically focus our attention on important matters.

From The World According to Peter Drucker by Jack Beatty

THE PRESIDENT knew the man needed no introduction, so, without a word of identification, he simply told the employees of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare assembled to hear his speech: “Peter Drucker says that modern government can do only two things well: wage war and inflate the currency.

It’s the aim of my administration to prove Mr. Drucker wrong.”

If Richard Nixon thought he did not have to identify Peter Drucker thirty years ago, must I do it now?

Drucker’s fame is planetary.

(The test of planetary is to have one of your novels be a best seller in Brazil.)

According to a recent book on management gurus, Peter Drucker is “one of the few thinkers in any discipline who can claim to have changed the world: he is the inventor of privatization, the apostle of a new class of knowledge workers, the champion of management as a serious discipline.”

Drucker has been called everything from “the father of management” to “the man who changed the face of industrial America” to “the one great thinker management theory has produced.”

On inspection these and other encomia about him turn out to be within caviling distance of being true.

This book attempts to show why.

Peter Drucker’s influence is global: his twenty-nine books have sold over five million copies, and they have been translated into nearly every language in the world.

His views on management, industrial organization, business strategy, leadership development, and employee motivation have tutored not just companies but countries—Drucker served as a guru to the postwar Japanese economic miracle—and he has an earned reputation for forecasting future social and economic trends.

His concepts and coinages are the stuff of contemporary management thought; they include “privatization “the knowledge worker,” “management by objectives,” “post-modern and “discontinuity” as a principle to understand this era of vertiginous change.

Drucker’s ideas and books gain authority from his work as a management consultant; for fifty years he has immersed himself in the management challenges of Fortune 500 corporations, museums, charitable foundations, churches, hospitals, small businesses, universities, governments, and even baseball teams—Yogi Berra was once a client.

...

snip, snip ...

the recurring paradox of Drucker’s career: the “man who invented the corporate society” has been a sometimes sulfuric critic of capitalist excess.

Indeed, Drucker, the author writes, should be seen as “a moralist of our business civilization”

See What do you want to be remembered for? and his bibliography.

Elizabeth Haas Edersheim wrote the following in The Definitive Drucker:

While interviewing former students and clients, I noticed a pattern.

Virtually everyone I interviewed said, at some time in the interview, one version or another of essentially the same thing: “Peter liberated me.

He elevated my expectations.”

I never really understood the power of liberation until I started hearing stories about it from so many people.

Peter’s ideas were the catalyst that freed people to pursue opportunities they had never expected to have.

He liberated people by asking them questions and eliciting a vision that just felt right.

He liberated people by getting them to challenge their own assumptions.

He liberated people by raising their awareness of, and their faith in, things they knew intuitively.

He liberated people by forcing them to think.

He liberated people by talking to them.

He liberated people by getting them to ask the right questions.

When I played this theme back to Warren Bennis, a longtime friend of Peter’s and one of today’s leading thinkers on organizational effectiveness, he responded, “Yes, I had never thought of it that way, but Peter Drucker does liberate.”

Warren sat back in his living room chair and smiled.

When I checked it with Richard Cavanagh, president of the Conference Board, he smiled and said, “Yes, I’ve seen him do that a lot.

I’ve even seen him liberate whole audiences as he spoke.”

A particularly poignant moment came when I was interviewing Tony Bonaparte, special assistant to the president at St. John’s University in New York.

With tears in his eyes, he looked at me and told me how Drucker had changed his career and his life.

Bonaparte had always wanted to teach at a community college.

He had a chance to attend the Executive MBA program at NYU.

There he met Drucker, who was a professor and teaching an evening class.

Drucker took an interest in him, and Peter and Doris started taking him out to dinner every few weeks.

Drucker would ask questions and implore Bonaparte to push, push, push to liberate himself.

“He made sure I always was stretching just a little further, liberating me from my constraints,” Bonaparte remembered.

“Each time I went back, my expectations of myself were higher.

He would not let me do anything but succeed.

And if it weren’t for him I wouldn’t be where I am today.

He looks at things as they are with a very realistic sense of how they could be and helped me do the same.

It changed my life.”

Drucker worked with great leaders for over 75 years and liberated them, too.

Churchill went so far as to say that the amazing thing about Peter Drucker was his ability to start our minds along a stimulating line of thought.

Mexican President Vicente Fox commented that Peter’s insights on societies were second to none.

Peter Drucker so increased the credibility of the concept of “management” that the U.S. Bureau of the Budget was renamed the Office of Management and Budget in 1970.

And, of course, Drucker liberated and inspired great corporate leaders, among them Akito Morita, founder of Sony; Andy Grove, one of the founders of Intel; Bill Gates of Microsoft; and Jack Welch, former chairman and chief executive of General Electric.

Peter Drucker’s Legacy

From Jim Collins introductory remarks in Management, Revised Edition

During a discussion in graduate school, a professor challenged my first-year class: managers and leaders—are they different? The conversation unfolded something like this:

“Leaders set the vision; managers just figure out how to get there,” said one student.

“Leaders inspire and motivate, whereas managers keep things organized,” said another.

“Leaders elevate people to the highest values. Managers manage the details.”

The discussion revealed an underlying worship of “leadership” and a disdain for “management.” Leaders are inspired. Leaders are large. Leaders are the kids with black leather jackets, sunglasses, and sheer unadulterated cool. Managers, well, they’re the somewhat nerdy kids, decidedly less interesting, lacking charisma. And of course, we all wanted to be leaders, and leave the drudgery of management to others.

We could not have been more misguided and juvenile in our thinking. As Peter Drucker shows right here, in these pages, the very best leaders are first and foremost effective managers. Those who seek to lead but fail to manage will become either irrelevant or dangerous, not only to their organizations, but to society.

Business and social entrepreneur Bob Buford once observed that Drucker contributed as much to the triumph of free society as any other individual. I agree. For free society to function we must have high-performing, self-governed institutions in every sector, not just in business, but equally in the social sectors. Without that, as Drucker himself pointed out, the only workable alternative is totalitarian tyranny. Strong institutions, in turn, depend directly on excellent management, and no individual had a greater impact on the practice of management and no single book captures its essence better than his seminal text, Management.

My first encounter with Drucker’s impact came at Stanford in the early 1990s, when Jerry Porras and I researched the great corporations of the twentieth century. The more we dug into the formative stages and inflection points of companies like General Electric, Johnson & Johnson, Procter & Gamble, Hewlett-Packard, Merck and Motorola, the more we saw Drucker’s intellectual fingerprints. David Packard’s notes and speeches from the foundation years at HP so mirrored Drucker’s writings that I conjured an image of Packard giving management sermons with a classic Drucker text in hand. When we finished our research, Jerry and I struggled to name our book, rejecting more than 100 titles. Finally in frustration I blurted, Why don’t we just name it Drucker Was Right, and we’re done!” (We later named the book Built to Last.)

What accounts for Drucker’s enormous impact? I believe the answer lies not just in his specific ideas, but in his entire approach to ideas, composed of four elements:

1. He looked out the window, not in the mirror

2. He started first—and always—with results

3. He asked audacious questions

4. He infused all his work with a concern and compassion for the individual.

I once had a conversation with a faculty colleague about the thinkers who had influenced us. I mentioned Drucker. My colleague wrinkled his nose, and said: “Drucker? But he’s so practical.” Drucker would have loved that moment of disdain, reveling in being criticized for the fact that his ideas worked. They worked because he derived them by precise observation of empirical facts. He pushed always to look out there, in the world, to derive ideas, challenging himself and his students to “Look out the window, not in the mirror!” Drucker falls in line with thinkers like Darwin, Freud and Taylor—empiricists all. Darwin wrote copious notebooks, pages and pages about pigeons and turtles. Freud used his therapeutic practice as a laboratory. Taylor conducted empirical experiments, systematically tracking thousands of details. Like them, Drucker immersed himself in empirical acts and then asked, “What underlying principle explains these facts, and how can we harness that principle?”

Drucker belonged to the church of results. Instead of starting with an almost religious belief in a particular category of answers—a belief in leadership, or culture, or information, or innovation, or decentralization, or marketing, or strategy, or any other category—Drucker began first with the question “what accounts for superior results?” and then derived answers. He started with the outputs—the definitions and markers of success—and worked to discover the inputs, not the other way around. And then he preached the religion of results to his students and clients, not just to business corporations but equally to government and the social sectors. The more noble your mission, the more he demanded: what will define superior performance? “Good intentions,” he would seemingly yell without ever raising his voice, “are no excuse for incompetence.”

And yet while practical and empirical, Drucker never became technical or trivial, nor did he succumb to the trend in modern academia to answer (in the words of the late John Gardner) “questions of increasing irrelevance with increasing precision.” By remaining a professor of management—not as a science, but as a liberal art he gave himself the freedom to pursue audacious questions. My first reading of Drucker came on vacation in Monterey, California. My wife and I embarked on one of our adventure walks through a used book store, treasure hunting for unexpected gems. I came across a beaten-up, dog-eared copy of Concept of the Corporation, expecting a tutorial on how to build a company. But within a few pages, I realized that it asked a much bigger question: what is the proper role of the corporation at this stage of civilization? Drucker had been invited to observe General Motors from the inside, and the more he saw, the more disturbed he became. “General Motors … can be seen as the triumph and the failure of the technocrat manager,” he later wrote. “In terms of sales and profits [GM) has succeeded admirably … But it has also failed abysmally—in terms of public reputation, of public esteem, of acceptance by the public.” Drucker passionately believed in management not as a technocratic exercise, but as a profession with a noble calling, just like the very best of medicine and law.

Drucker could be acerbic and impatient, a curmudgeon. But behind the prickly surface, and behind every page in his works, stands a man with tremendous compassion for the individual. He sought not just to make our economy more productive, but to make all of society more productive and more humane. To view other human beings as merely a means to an end, rather than as ends in themselves, struck Drucker as profoundly immoral. And as much as he wrote about institutions and society, I believe that he cared most deeply about the individual.

I personally experienced Drucker’s concern and compassion in 1994, when I found myself at a crossroads, trying to decide whether to jettison a traditional path in favor of carving my own. I mentioned to an editor for Industry Week that I admired Peter Drucker. “I recently interviewed Peter,” he said, “and I’d be happy to ask if he’d be willing to spend some time with you.”

I never expected anything to come of it, but one day I got a message on my answering machine. “This is Peter Drucker”—slow, deliberate, in an Austrian accent—"I would be very pleased to spend a day with you, Mr. Collins. Please give me a call.” We set a date for December, and I flew to Claremont, California. Drucker welcomed me into his home, enveloping my extended hand into two of his. “Mr. Collins, so very pleased to meet you. Please come inside.” He invested the better part of a day sitting in his favorite wicker chair, asking questions, teaching, guiding, and challenging. I made a pilgrimage to Claremont seeking wisdom from the greatest management thinker, and I came away feeling that I’d met a compassionate and generous human being who—almost as a side benefit—was a prolific genius.

There are two ways to change the world: the pen (the use of ideas) and the sword (the use of power). Drucker chose the pen, and thereby rewired the brains of thousands who carry the sword. Those who choose the pen have an advantage over those who wield the sword: the written word never dies. If you never had the privilege to meet Peter Drucker during his lifetime, you can get to know him in these pages. You can converse with him. You can write notes to him in the margins. You can argue with him, be irritated by him, and inspired. He can mentor you, if you let him, teach you, challenge you, change you—and through you, the world you touch. (calendarize this)

Peter Drucker shined a light in a dark and chaotic world, and his words remain as relevant today as when he banged them out on his cranky typewriter decades ago. They deserve to be read by every person of responsibility, now, tomorrow, ten years from now, fifty and a hundred. That free society triumphed in the twentieth century guarantees nothing about its triumph in the twenty-first; centralized tyranny remains a potent rival, and the weight of history is not on our side. When young people ask, “What can I do to make a difference?” one of the best answers lies right here in this book. Get your hands on an organization aligned with your passion, if not in business, then in the social sectors. If you can’t find one, start one. And then lead it—through the practice of management—to deliver extraordinary results and to make such a distinctive impact that you multiply your own impact by a thousand-fold.

Jim Collins

Boulder, Colorado

December, 2007

How to Consult Like Peter Drucker

In addition to being considered “the man who invented management,” Drucker was arguably the father of management consulting (with all due respect to McKinsey & Co.’s Marvin Bower).

In fact, Drucker had recently arrived in the United States from Europe when he was summoned to serve as a “management consultant” for the Army, shortly before World War II.

There was just one hitch: A journalist and lecturer, with a bit of background in finance and a doctorate in international law, the then-30-something Drucker wasn’t quite sure what a consultant actually did.

He scoured the library, but the field was so new, he couldn’t locate any answers there.

His friends were clueless, as well.

So Drucker tried to get clarification from the colonel to whom he was supposed to report.

“Young man, don’t be impertinent,” the officer shot back—“by which,” Drucker later recounted, “I knew that he didn’t know what a management consultant did, either.”

Drucker figured it out pretty quickly.

By the mid-1940s, he had found his way deep inside General Motors, and by the 1950s he was consulting for Sears, General Electric and IBM.

Over the decades, he’d add a host of other major companies and nonprofits to his client list: Intel, Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola, the American Red Cross, the Salvation Army and many more.

Why was Drucker so in demand?

What made him so good?

For starters, he understood that his job wasn’t to serve up answers.

“My greatest strength as a consultant,” Drucker once remarked, “is to be ignorant and ask a few questions.”

In many cases, they were deceptively simple: Who is your customer?

What have you stopped doing lately (so as to free up resources for the new and innovative)?

What business are you in?

Or, as he urged the founders of the investment bank Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette to ask themselves in 1974, after they had enjoyed a heady period of growth: “What should our business be?”

“I shall not attempt to answer the question what your business should be,” Drucker added.

“First, one should not answer such a question off the top of one’s head.

… Secondly, one man’s opinion, no matter how brilliant, is at best one man’s opinion.”

Besides, Drucker said, “I can only ask questions.

The answers have to be yours.”

Other times, of course, corporations sought Drucker’s counsel to deal with narrower challenges.

In 1992, for example, he wrote a 56-page analysis for Coca-Cola that explored distribution, branding, advertising, the structure of the company’s bottling operations and more.

Still, the approach was always the same: “This report raises questions,” Drucker told Coke.

“It does not attempt to give answers.”

Another thing that made Drucker stand apart was his integrity.

He wouldn’t come in, do a job—and then stick his client with the bill without knowing whether he had made a real difference.

“Remember,” Drucker told the assistant to the chairman of Sears, as he turned in an invoice in March 1955, “that this is submitted on condition that there is no payment due unless the work satisfies you.”

Indeed, Drucker knew that the test wasn’t whether he had delivered some sharp insight.

All that counted was whether his client could use that insight to make measurable progress on an important issue.

It’s the performance of others, Drucker wrote, that “determines in the last analysis whether a consultant contributes and achieves results, or whether he is … at best a court jester.”

In this respect, Drucker knew that the most dangerous thing for any consultant was to become too impressed with his own wisdom.

He didn’t like his clients getting carried away, either.

“Stop talking about ‘Druckerizing’ your organization,” he told officials at Edward Jones, the investment firm.

“The job ahead of you is to ‘Jonesize’ your organization—and only if you accept this would I be of any help to you.

Otherwise, I would rapidly become a menace—which I refuse to be.”

Oh, and one other thing: Peter Drucker never drew a four-box matrix in his entire life.

Introductory reading

Examples of Drucker’s Writing and Thinking

See a combined outline of many of these books

It would probably be informative to contrast and compare the subject and contents of his work with the course outlines of the prominent business (management) schools (Google: recruiter OR recruiters “top business schools”). My perception of the difference: the schools focus on tools and tool boxes while Peter Drucker focuses on what works—from a broad strategic viewpoint—in TIME. Tools are valuable to the extent that they serve a desired end.

It has been noted that hyperbole is often present in Peter Drucker’s work. I believe he used it as a device for focusing attention. Our brains tend to dismiss ideas cloaked in cautious language.

TLN keywords: tlnkwdrucker tlnkwmanagement

|

![]()

![]()