Adventures of a Bystander

by Peter Drucker

Jump to main text

Bibliography for many of Drucker's books

Amazon link: Adventures of a Bystander

See about management

Quotes from Amazon.com book page

An amazing pageant of characters, both famous and otherwise, springs from these pages, illuminating and defining one of the most tumultuous periods in world history.

Along with bankers and courtesans, artists, aristocrats, prophets, and empire-builders, we meet members of Drucker’s own family and close circle of friends, among them such prominent figures as Sigmund Freud, Henry Luce, Alfred Sloan, John Lewis, and Buckminster Fuller.

Playing to perfection their roles as those who “reflect and refract” the customs, beliefs, and attitudes of the times, these singular personalities lend Adventures of a Bystander a striking “you-are-there” feel.

I laughed and I cried as I read Adventures of a Bystander.

I have always had enormous respect for Professor Drucker, but this book has taken my respect and awe of him to another plateau.

To learn how and what Professor Drucker thought as a child and how many momentous decisions he made by the time he was fourteen helps us understand him as a person and the environment from which all of his other works come.

My grandmother also grew up in Austria and the “Grandmother stories” brought back very precious memories.

Once again, even as a youngster, we see Professor Drucker uncannily knowing what will happen by studying (by living) the events of the times.

One cannot really understand and appreciate Professor Drucker and his other works without reading this book, and yet, reading many of his other works first, made me appreciate Adventures of a Bystander even more.

Contents of Adventures of a Bystander

Preface to the New Edition

Prologue: A Bystander Is Born

Report From Atlantis

Grandmother And The Twentieth Century Grandmother And The Twentieth Century

Hemme And Genia Hemme And Genia

Miss Elsa And Miss Sophy (great teachers) Miss Elsa And Miss Sophy (great teachers)

Freudian Myths And Freudian Realities Freudian Myths And Freudian Realities

Count Traun-Trauneck And The Actress Maria Mueller Count Traun-Trauneck And The Actress Maria Mueller

Young Man In An Old World

The Polanyis The Polanyis

The Man Who Invented Kissinger The Man Who Invented Kissinger

The Monster And The Lamb The Monster And The Lamb

Noel Brailsford—The Last Of The Dissenters Noel Brailsford—The Last Of The Dissenters

Ernest Freeberg’s World Ernest Freeberg’s World

The Bankers And The Courtesan The Bankers And The Courtesan

The Indian Summer Of Innocence

Henry Luce And Time-Life-Fortune Henry Luce And Time-Life-Fortune

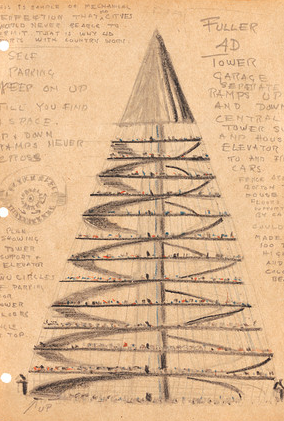

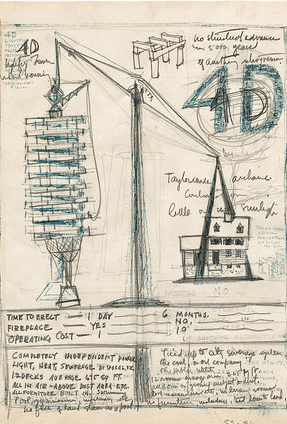

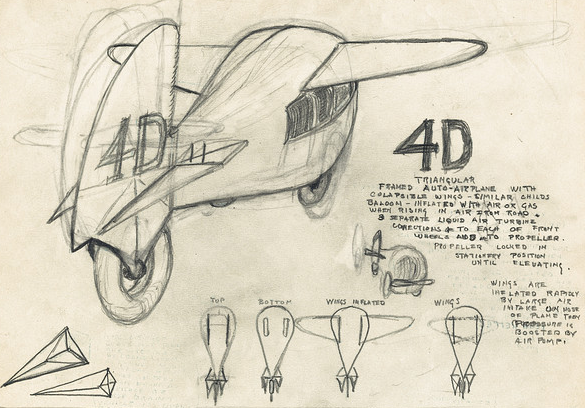

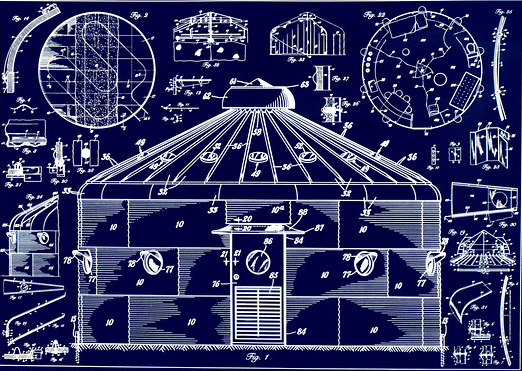

The Prophets: Buckminster Fuller And Marshall McLuhan The Prophets: Buckminster Fuller And Marshall McLuhan

The Professional: Alfred Sloan (My Years with General Motors) The Professional: Alfred Sloan (My Years with General Motors)

The Indian Summer Of Innocence The Indian Summer Of Innocence

See What do you want to be remembered for?

Preface to the New Edition

I taught religion once, many years ago, and I greatly enjoyed it.

(see The Unfashionable Kierkegaard and The Happiness Purpose)

But I never had much use for theology.

There are, I am told, some thirty-five thousand different species of flies.

But if the theologians had their way, there would be only one, the right Fly.

The Creator glories in diversity.

And no species is more diverse than those two-legged creatures, Men and Women.

(See mental patterns for an explanation of this diversity.)

Even as a small child I marvelled at their diversity.

And I have never met a single uninteresting person.

No matter how conformist, how conventional, or how dull, people become fascinating the moment they talk of the things they do, know, or are interested in.

Everyone then becomes an individual.

The most conventional person I can recall, a banker in a small New England town, who seemed to know nothing but the most hackneyed clichés, became fascinating when he suddenly started talking about buttons throughout the ages—their invention, their shapes, their materials, their functions and uses—with a fire and passion worthy of a great lyrical poet.

The subject did not interest me much; the man did.

He had become an individual.

And individuals in their diversity are portrayed in this book.

It is this belief in diversity and pluralism and in the uniqueness of each person that underlies all my writings, beginning with my first book (The End of Economic Man) more than fifty years ago.

During most of these fifty years centralization, uniformity, and conformity were dominant.

The totalitarian regimes (The End of Economic Man) in which everybody was to conform, to think the same, to write and paint the same, to be centrally controlled—the Nazis called it “switched onto the same track” (gleichgeschaltet)—were but the head of a universal current.

It swept over the democracies as well.

But every one of my books and essays, whether dealing with politics, philosophy, or history; with social order and social institutions; with management, technology, or economics, has stressed pluralism and diversity.

Where the prevailing doctrines preached control by big government or big business, I stressed decentralization, experimentation, and the need to create community.

And where the prevailing approaches saw government and big business as the only institutions and as the “countervailing powers” of a modern society, I stressed the importance and central role of the non-profit, public-service institutions, the “third sector”—as the nurseries of independence and diversity; as guardians of values; as providers of community leadership and citizenship.

sidebar → but there’s no virtue in being a non-profit

And I pointed out how much of society is organized and informed by non-business, non-governmental institutions, the universities, for instance, or the hospitals, each with very different values and a different personality.

But I was swimming against a strong current.

Now, at last, the tide has turned, and it has turned my way.

The flag-bearer of the collectivist, centralizing, uniformity-imposing parade, Communism, has proven a sham, incompetent even to provide the mere rudiments of effective government, functioning economy, citizenship, and community.

And in the West too we are now rapidly decentralizing, indeed uncentralizing.

For a generation after World War II, we believed that any sickness was best treated in a centralized hospital, the bigger the better.

We are now moving patients into “outreach” facilities as fast as we can.

During the last fifteen years America’s large corporations have been shrinking steadily.

All the phenomenal employment growth in this period—the fastest growth in jobs in peacetime history anywhere—has been in small and middle-sized enterprises.

In the decades following World War II, America built ever-bigger consolidated schools—one cause, I believe, of our educational malaise.

Now we are moving towards diverse, decentralized schools, the “magnet schools,” for instance.

(See chapter 14, “The Accountable School” in Management, Revised Edition)

“Small is beautiful” is, of course, as much stifling dogma as “big is best”—and equally stupid, as one look at the diversity of God’s creation will show.

We surely will not return to the nineteenth-century society, which knew only the smallest and weakest of governments and few institutions except the local church and school.

The knowledge society into which we are moving so fast is going to be a society of organizations.

But of organizations—plural—that will be diverse, decentralized, multiform.

See sidebar below

And within these organizations, we are moving away from the standardized, uniform structures that were generally accepted in public administration and business management, “the one right structure for the typical manufacturing company,” for instance, or the “model government agency.”

We are moving toward organic design, informed by mission, purpose, strategy, and the environment, both social and physical—the design I began to advocate forty years ago in The Practice of Management (which came out in 1954). …

Sidebars ↓ : … to pursue the preceding line of thought

The Management Revolution The Management Revolution

How To Guarantee Non-Performance How To Guarantee Non-Performance

Innovation as a normal activity Innovation as a normal activity

Management’s New Paradigm ↓ Management’s New Paradigm ↓

… the center of a modern society, economy and community is not technology.

It is not information.

It is not productivity.

The center of modern society is the managed institution.

The managed institution is society’s way of getting things done these days.

And management is the specific tool, the specific function, the specific instrument, to make institutions capable of producing results.

The institution, in short, does not simply exist within and react to society.

It exists to produce results on and in society.

… and Management, Revised Edition contains a “Management’s New Paradigm” chapter with a different “thoughtscape” a.k.a. “brainscape.”

Management Cases (Revised Edition) provides a more day-to-day, issue-to-issue, situational “landscape” view. Management Cases (Revised Edition) provides a more day-to-day, issue-to-issue, situational “landscape” view.

“From Analysis to Perception — The New World View” found in The New Realities or The Essential Drucker. “From Analysis to Perception — The New World View” found in The New Realities or The Essential Drucker.

Form and Function Connections ↑: see chapters On Being the Right Size and On Being the Wrong Size in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices and others. (calendarize this?)

main brainroad continues ↓

… But while my writings for fifty years have been stressing organic design, decentralization, and diversity, they deal with ideas, that is, with abstractions.

They draw heavily on my work with people as a teacher and as a consultant.

Remembered for?

And I always try to bring in people to exemplify and to illustrate.

But still, these individuals are being used to exemplify and to illustrate concepts.

I myself have always been more interested in people than in concepts.

But I have known all along that as a writer I do better with concepts than with people.

Adventures of a Bystander is thus a book I wrote for myself.

It is a book about people.

Not about myself; the subtitle of the British edition describes my intention: Other Lives and My Times.

No book of mine has had a longer gestation period; for twenty years I lived with the characters in my head, ate, drank, walked, talked with them, awake and in my dreams.

But no book of mine has come into the world faster—it took less than a year to complete once I sat down at the typewriter.

It is surely not my “most important” book.

But it is the one I enjoy the most.

And so apparently do my readers.

That the book has had success—more than enough to justify reissuing it in this new edition—is, of course, gratifying in itself.

But what is even nicer are the readers who write or who tell me when I encounter them in a meeting: “I have read many of your books, have learned a great deal from them, and use them constantly in my work.

(A possible methodology)

But of all your books I enjoy most Adventures of a Bystander.”

And then they often add: “I enjoy it so much because the people in it are so diverse.”

I chose the people in this book because of their diversity and because I enjoyed their stories the most.

But as an early reviewer pointed out, they also “signify.”

They were not picked because they were “great and famous.”

Indeed, most of them were totally obscure; the telephone directory was the only “reference book” ever to list them.

What holds them together is pure chance: they crossed my path.

But still, I think, their individual tales create a tapestry.

In a subjective, eclectic way, they convey, I hope, something of the atmosphere, the ambience, of a time that is rapidly fading—even in the recollection of older people: that very peculiar half-century between pre-World War I Europe and post-World War II America.

Each story is separate.

Each was picked because it made a good story.

But together, I believe, they show that history is, after all, composed of stories.

Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie — micro-history

Memorial Day, 1990 Claremont, California

Prologue: A Bystander Is Born

Bystanders have no history of their own.

They are on the stage but are not part of the action.

They are not even audience.

The fortunes of the play and of every actor in it depend on the audience whereas the reaction of the bystander has no effect except on himself.

But standing in the wings—much like the fireman in the theater—the bystander sees things neither actor nor audience notices.

Above all, he sees differently from the way actors or audience see.

Bystanders reflect—and reflection is a prism rather than a mirror; it refracts.

This book is no more a “history of our times,” or even of “my times,” than it is an autobiography.

It uses the sequence of my life mainly for the order of appearance of its dramatis personae.

It is not a “personal” book; my experiences, my life, and my work are the book’s accompaniment rather than its theme.

But it is an intensely subjective book, the way a first-rate photograph tries to be.

It deals with people and events that have struck me—and still strike me—as worth recording, worth thinking about, worth rethinking and reflecting on, people and events that I had to fit into the pattern of my own experience and into my own fragmentary vision of the world around me and the world inside me.

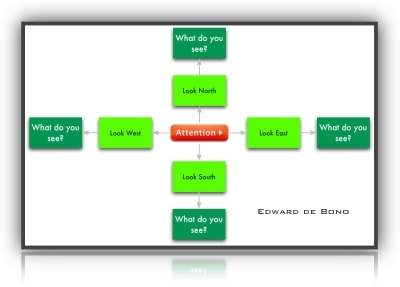

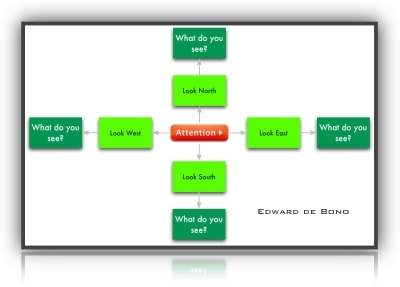

Attention

I was still a week shy of my fourteenth birthday when I discovered myself to be a bystander.

The day was November 11, 1923—my birthday is on the nineteenth.

November 11 in the Austria of my childhood was “Republic Day,” commemorating the day, in 1918, on which the last of the Habsburg emperors had abdicated and the Republic was proclaimed.

For most of Austria this was a day of solemnity, if not of mourning—the day of final defeat in a nightmare war, the day in which centuries of history had crumbled into dust. …

… If you decide to read the book, be sure to identify the key people and events in each chapter: “people and events that have struck me—and still strike me—as worth recording, worth thinking about, worth rethinking and reflecting on.”

Attention

Then you might consider what these ideas mean for you in each of your life roles, what action is needed …

Also see Drucker's "My Life as a Knowledge Worker" and The Management Revolution

Grandmother and the Twentieth Century

I had not been back for almost twenty years when I visited Vienna in 1955 to give one or two lectures.

And even earlier, before I last stopped over in 1937 en route from England to America, I had been in Vienna only infrequently.

I had left as soon as I finished the Gymnasium, in 1927, not quite eighteen, and returned later only to spend Christmases with my parents, rarely for more than a week at a time.

In 1955 I was going to stay only long enough to give my lectures.

But as I was walking outside my hotel the morning after my arrival, I passed a food market that had been a byword for choice delicacies in my childhood.

I remembered that I had promised my wife back in America a bottle of a particular Austrian liqueur, so I went into the store to buy it.

I did not remember ever having been there—certainly I had not been a regular customer.

But as I went through the door, the ancient lady who, according to old and by then thoroughly outmoded custom, presided over the store from the cash register, recognized me at once and hailed me by name.

“Mr. Peter,” she said, “how nice of you to visit us.

We read in the papers that you were coming here to lecture and wondered whether we’d see you.

We were very sorry to hear last year that your dear mother had passed away; and of course your dear Aunt Anna has been gone a long time now.

But I hear that your esteemed father is still alive and well.

Is it true that we can expect him in Vienna next year to celebrate his eightieth birthday?

Your Aunt Greta was here only a few years ago when your Uncle Hans got the honorary doctorate.

Being suppliers to the family from the old days, we didn’t think it would be presumptuous for us to send a hamper of fruit and a note of congratulations to their hotel, and we got such a gracious letter back from your Aunt Greta.

Those were lovely ladies.

The young people here,” and she nodded toward the sales personnel in the store, “don’t know real quality any more.

But, begging your pardon, Mr. Peter, none could compare with your grandmother.

What a wonderful lady she was; there was no one like her.

We live in the world we see

And,” she began to smile, “she was so funny!

Do you remember the story of her telegram to her niece’s wedding?”

She broke into loud cackling laughter and I joined her.

Of course I knew the story of Grandmother’s telegram, even though it was sent well before I was born.

Unable to attend the wedding of a niece, Grandmother had wired:

Since it is considered proper and good form to confine oneself to the utmost brevity in sending a telegram let me only wish you on this solemn day MANY HAPPY RETURNS.

Then, according to family legend, Grandmother had complained bitterly that they charged so much when she was only wiring three words.

Grandmother was tiny and small-boned and had been beautiful in her youth.

When I came to know her there were hardly any traces of youth and beauty left—except for her abundant curly hair, still a warm red-brown, of which she was very proud.

Shortly after her husband died and left her a widow when barely forty, she had had a long siege of illness:

the serious infection then called rheumatic fever that left her with permanent heart damage and perennially short of breath.

She was badly crippled by arthritis, and all her bones, especially in the fingers, were swollen and painful.

As the years went by she also became increasingly deaf.

Yet nothing stopped grandmother from being on the go all the time and in every weather.

She would visit all over the city, by streetcar or, more often, on foot.

She was always armed with a big black umbrella that doubled as a cane, and lugged an enormous black shopping bag that weighed as much as she did and was full of tiny mysterious packages, individually wrapped—a few ounces of herb tea for an ailing old woman, a few postage stamps for a schoolboy, half a dozen “good” metal buttons from a discarded frock as a present for a dressmaker, and so on.

Grandmother was one of six sisters, every one of whom in turn had had at least four daughters, so that there were innumerable nieces.

Most of them had been brought up by Grandmother at one time or another and were closer to her than to their own mothers.

But there were also old family servants and retainers, elderly ladies in reduced circumstances and former fellow music students, old shopkeepers and craftsmen, and even old servants of long-dead friends.

“If I don’t visit her, who will do it?”

Grandmother would say when she set out for a long trip to some outlying suburb to look up “Little Paula,” the elderly widowed niece of her cousin’s long-deceased housekeeper.

And everyone, including her daughters and her nieces, had come to call her “Grandmother.”

She spoke to everybody the same way, in the same pleasant friendly voice, and with the same old-fashioned courtesy.

She always remembered what was important to everyone she met even if she had not seen them in a long time.

“Tell me, Miss Olga,” she would say to the governess of the children next door to us, whom she had not seen for months, “how is that nephew of yours coming along?

Has he passed that final engineering exam by now?

Oh, you must be so proud of him.”

Or to the old cabinetmaker whose father had made the furniture for her trousseau and whom she dropped in to see once in a while for old time’s sake:

“Have you been able to get the city to cancel the increase in the real estate tax on your shop, Mr. Kolbel?

You were upset about it the last time we met.”

Grandmother spoke the same way to the prostitute who had her stand at the street corner next door to the apartment house where she lived.

Everyone else would pretend not to see the woman.

But Grandmother would always wish her a good evening and say, “It’s a cold wind tonight, Miss Lizzie.

Do you have a warm scarf and is it wrapped tight?”

And one evening when she noticed that Miss Lizzie was hoarse, Grandmother crawled up the five flights to her apartment—this was postwar Vienna and elevators rarely functioned—rummaged in her medicine cabinet for cough drops, then painfully crawled down again to give them to Miss Lizzie.

“But Grandmother,” remonstrated one of her stuffier nieces, “it’s improper for a lady to talk to a woman like her.”

“Nonsense,” Grandmother said, “to be courteous is never improper.

I am not even a man; what that’s improper could she want with a stupid old woman like me?”

“But Grandmother, to bring her cough drops!”

“You,” Grandmother said, “always worry about the horrible venereal diseases the men get from these girls.

I can’t do anything about that.

But I can at least prevent her from giving a young man a bad sore throat.”

One of Grandmother’s nieces—or maybe a grandniece—had become a starlet of film and musical comedy whose love affairs were forever being reported in the more lurid Sunday papers.

“I wouldn’t mind,” said Grandmother, “if I never heard another word about what goes on in Mimi’s bedroom.”

“Oh, Grandmother, don’t be a prude,” a granddaughter said.

“I know,” said Grandmother, “she has to have these affairs and I know she has to get them in the papers.

It’s the only way she can get a decent part; she has no voice and can’t act.

But I wish she wouldn’t name those awful men in her interviews.”

“But Grandmother,” the granddaughter said, “the men love it.”

“That’s just what I object to,” snapped Grandmother; “pandering to the vanity and conceit of those dirty old lechers.

I call it prostitution.”

Grandmother’s marriage had apparently been very happy.

To her dying day, she kept her husband’s portrait in her bedroom and went into seclusion on the anniversary of his death.

Yet he had been a notorious philanderer.

When I was about seventeen and walking down one of Vienna’s main streets, an ancient chauffeur-driven automobile passed me, then stopped.

A hand waved at me out of the rear window.

I went up and saw two women sitting inside, one heavily veiled, the other a maid, judging by her apron.

The maid said to me:

“My lady thinks you might be Ferdinand Bond’s grandson.”

Yes, I was.

The maid said:

“He was my lady’s last lover”—and the car drove off.

I was terribly embarrassed, but apparently not embarrassed enough to keep quiet.

The story got to Grandmother, who called me in and cross-examined me about the veiled lady in the car.

Then she said, “It must have been Dagmar Siegfelden.

I can well believe that your grandfather was her last lover—poor woman, she was never very attractive.

But you can take it from me, she was not your grandfather’s last mistress.”

“But Grandmother,” I said—we were forever, it seems, saying, “But Grandmother”—“didn’t his having mistresses bother you?”

“Of course it did,” said Grandmother.

“But I would never have a husband who didn’t have mistresses.

I’d never know where he was.”

“But weren’t you afraid he might leave you?”

“Not in the least,” said Grandmother.

“He always came home to eat dinner.

I am only a stupid old woman, but I know enough to realize that the stomach is the male sex organ.”

Grandmother’s husband had left her a large fortune.

But it all went in the Austrian inflation, and Grandmother had become poor as a church-mouse.

She had lived in a big two-story apartment with plenty of servants; now she lived in a corner of her former maids’ quarters and kept house all alone.

Her health grew steadily worse.

Yet the only thing she ever complained about—and that rarely—was that arthritis and deafness increasingly prevented her from playing and listening to music.

In her young days she had been a pianist, one of Clara Schumann’s pupils and asked by her several times to play for Johannes Brahms, which was Grandmother’s proudest memory.

A girl of good family could not become a public performer, of course.

But until her husband died and she fell ill, Grandmother often played at charity concerts.

One of her last performances had been under Mahler’s baton shortly after he had taken over as conductor of the Vienna Opera in 1896.

She had no use for the big romantic sensuous sound that the Viennese loved.

She called it “stockjobbers’ music,” and considered it vulgar.

Instead, Grandmother anticipated by half a century the dry, unadorned, precise “French” style that has become popular in the last twenty years.

She never used the pedals.

Altogether she disliked sentiment in music.

When she sat with us children while we practiced, she would always say, “Don’t play music, play notes.

If the composition is any good, that will make music out of it.”

She had on her own discovered the French Baroque masters—Lully, Rameau and, above all, Couperin—who were then totally out of fashion.

And she played them with a dry, even, harpsichord-like sharpness rather than with the sonority of the “grand piano” which, of course, had not been invented when the music was written.

She had a remarkable musical memory.

I once practiced a sonata.

Grandmother came in from the next room and said, “Play that bar again.”

I did so.

She said:

“That should be a D flat; you played a D.”

“But Grandmother,” I said, “the score says ‘D.’”

“Impossible!”

Then she looked at the score and found that it did say “D.”

Whereupon she called up the publisher—he was of course the husband of one of her nieces—and said, “On this or that page of your second volume of Haydn Piano Sonatas, in bar so-and-so, there is a misprint.”

And he called back two hours later to tell her that she had been right.

“How did you know this, Grandmother?” we would say.

“How could I not know it?” she came back.

“I played the piece when I was your age and in those days we were expected to know our pieces.”

We all adored her.

But we all knew she was very funny indeed.

Like the lady in the delicatessen, we smiled when her name came up, then broke out laughing when we remembered this or that “Grandmother story.”

For we all knew that she, with all her wonderful qualities, was the family moron.

Every member of the family, from the oldest to the youngest, dined out on “Grandmother stories.”

They could make even the dullest and most tongue-tied of us the life of the party.

Our playmates, when we were still quite small, would clamor:

“Do you have any new Grandmother stories?” and would break out in guffaws of laughter when we told them.

As for instance:

After years of being badgered by one of her sons-in-law, Grandmother finally set to work cleaning up her kitchen cabinet.

She then proudly displayed the new order.

Tacked onto the top shelf was a card on which Grandmother had written in her Victorian hand:

“Cups without Handles.”

Beneath it, on the next shelf, the card read:

“Handles without Cups.”

The day came when Grandmother couldn’t keep all her stuff in the two tiny rooms to which she was finally reduced.

So she packed everything she didn’t need into enormous shopping bags and took off for the bank in the center of the city where she kept her account, by then down to a few pennies.

Her husband had started the bank and had been its chairman until he died, and she was still treated with the consideration due his widow.

But when she appeared with her shopping bags and asked to have the contents put on her account, the manager balked.

“We can’t put things on an account,” he said, “only money.”

“That’s mean and ungrateful of you,” said Grandmother; “you only do this to me because I am a stupid old woman.”

And she promptly closed her account and drew out the balance.

Then she went down the street to the nearest branch of the same bank, reopened her account there, and never said a word about her shopping bags.

“Grandmother,” we’d say, “if you thought the bank was unfriendly, why did you reopen your account at another branch?”

“It’s a good bank,” she said; “after all, my late husband founded it.”

“Then why not demand that the manager at the new branch take your stuff?”

“I never banked there before.

He didn’t owe me anything.”

Grandmother’s troubles over her apartment were a never-ending source of stories.

She sublet it to a dentist who used one floor to live in and one floor for his office, with Grandmother keeping a few rooms in the back for herself.

But she and the dentist soon began to quarrel and engaged for years in a running fight-suing each other, claiming damages, and even filing criminal charges against one another.

Yet Grandmother kept on going to Dr. Stamm to have her teeth treated and her dentures made.

“How can you patronize a dentist you just had arrested for criminal trespass?” we would ask.

“I am only a stupid old woman,” Grandmother would reply, “but I know he’s a good dentist or else how could he afford those two big floors?

And he is convenient; I don’t have to go out in bad weather or climb stairs.

And my teeth are not part of the lease.”

There was the story of how she threw a waitress out of her own restaurant.

She was traveling with four or five of us grandchildren—to take us to a summer camp, I believe.

When we changed trains we went into the station restaurant for lunch, and Grandmother noticed the slovenly waitress.

As the girl came close to our table, Grandmother hooked her with her umbrella handle and said quite pleasantly:

“You look like an educated, intelligent girl to me.

You wouldn’t want to work in a place where the staff doesn’t know how to behave, would you?

Go out that door,” Grandmother gave her a mighty shove with the umbrella toward the exit, “come in again and do it properly.”

The girl went meekly; and when she came in, she curtseyed.

We were terribly embarrassed and protested:

“But Grandmother, we aren’t going to be in this place ever again.”

“I hope not,” said Grandmother, “but the waitress has to be.”

And there was the cryptic advice she always gave to her granddaughters:

“Girls, put on clean underwear when you go out.

One never knows what might happen.”

When one granddaughter, half amused and half offended, said to her:

“But Grandmother, I’m not that kind of a girl,” Grandmother answered:

“You never know until you are.”

Grandmother held fast to “prewar.”

But her standard was not 1913; it was the time before her husband had died—especially in regard to money.

Austria had had a silver currency for most of the nineteenth century, the Gulden, which contained 100 Kreuzer.

Then in 1892, when Grandmother was a young woman of thirty-five or so, Austria switched to a gold currency, the Krone, with 100 Heller—each Gulden being exchanged into 2 Kronen.

Thirty years later inflation destroyed the Krone.

When it had depreciated to the point where it took 75,000 Kronen to buy what one had bought before the war, a new currency came in—the Schilling, each exchanged for 25,000 of the old Kronen.

Within a year or less everybody thought only in terms of the Schllhing, except for Grandmother.

She stayed with the Gulden when she went shopping.

She would laboriously translate prices from Schilling first into Kronen before the exchange, then into Kronen before World War I, and finally into Gulden and Kreuzer.

“How come the eggs cost so much?” she’d say.

“You ask thirty-five Kreuzer a dozen for them—they used to cost no more than twenty-five.”

“But, gracious lady,” the shopkeeper would reply, “it costs more these days to feed the hens.”

“Nonsense,” said Grandmother, “hens aren’t Socialists.

They don’t eat more just because we have a Republic.”

My father, who was the economist in the family, tried to explain to her that prices had changed.

“Grandmother,” he said, “you have to realize that the value of money has changed because of war and inflation.”

“How can you say that, Adolph?”

Grandmother retorted.

“I am only a stupid old woman but I do know that you economists consider money the standard of value.

You might as well tell me that I am suddenly six feet tall because the yardstick has changed.

I’d still be well below average height.”

My father gave up in disgust.

But because he was as fond of Grandmother as we all were, he tried to help her.

At least he could relieve her of the chore of computing all those prices—multiplying by 25,000 and then by 3 and then by 2, or whatever it was Grandmother had to do to get back to what eggs had cost in 1892.

He made a conversion chart and presented it to her.

“How sweet of you, Adolph,” she said.

“But it doesn’t really help me unless it also tells me what things did cost back in those years.”

“But Grandmother,” my father said, “you know that—you always point out what eggs or lettuce or parsley used to cost in Gulden.”

“I am only a stupid old woman,” replied Grandmother, “but I have better things to do than stuff my brain with trivia like the price of parsley thirty years ago.

Besides I didn’t shop in those days; I had a housekeeper and a cook to do that.”

“But,” my father argued, “you always tell the shopkeepers that you know.”

“Of course, Adolph,” said my Grandmother; “you have to know or they’ll cheat you every time.”

But Grandmother was at her best—or worst—when dealing with officialdom and politics.

Before 1918 no one had a passport and no one had even heard of a visa.

Then suddenly one could not travel anywhere without both, and especially not from one part of what used to be the old Austria to another.

But also, in those first few years after the break-up of the old Austria, each of the successor states tried to make it as difficult and disagreeable as possible for the citizens of its neighbors to come in and for its own citizens to get out.

To get a passport one had to stand in line for hours—and then usually come back again because no one had the right papers, or even knew what papers were needed.

To get a visa one had again to stand in line for hours—and again, usually, come back.

And of course one had to go in person, accompanied by every member of the family who might go along on the trip.

At the new border stations everybody had to go out and stand in line in the open for hours, regardless of weather, then do the same all over again for the customs.

So when Grandmother announced in the summer of 1919 that she was going to visit her oldest daughter who, a year earlier, had married and moved to Budapest in Hungary, everybody tried to argue her out of the harebrained idea.

But no one ever changed Grandmother’s mind once it was made up.

My father was then the senior civil servant at the Austrian Ministry of Economics.

So Grandmother, without telling him, went to the ministry’s messenger and had him get her the passports and the visa.

And she got passports, where everybody else had a hard enough time to get one.

Her late husband had been a British subject—that he had died twenty years earlier one did not need to tell anyone; and so she got a British passport.

She herself had lived all her life in Vienna, so she got an Austrian passport.

While her husband was alive he had an apartment in Prague, where he often went on business; of course the apartment had been sold when he died, but one doesn’t have to volunteer information to authority—and so she got a Czech passport.

Next she wrote her daughter in Budapest to get a Hungarian passport for her.

And she got the needed visas into each of these four passports the same way.

When my father heard all this, he exploded.

“The ministry’s messenger is a public servant and must not be used on private business,” he shouted.

“Of course,” said Grandmother; “I know that.

But am I not a member of the public?”

She had me put into the passports and visas as a minor accompanying her.

“Why should Peter come with you to Budapest?” my parents asked.

“You know very well,” said Grandmother, “that he only practices the piano when I sit with him; and he has so little talent he can’t afford to miss two weeks of practicing.”

When we got to the border, the police ordered everybody out with their luggage.

But Grandmother stayed in her seat until the last person had entered the small shed at the end of the platform in which passports were inspected.

Then she hobbled to the passport office, black umbrella and shopping bag on one arm, me on the other.

The official was about ready to close up and had already taken down the sign.

“Why didn’t you come earlier?” he snarled.

“You were busy,” said Grandmother.

“You had people standing in line.”

With that she plonked the four passports on the table in front of him.

“But no one,” said the man, taken aback, “can have four passports.”

“How can you say that?” said Grandmother.

“Can’t you see I have four?”

The clerk, thoroughly beaten, said meekly, “But I can only stamp one.”

“You are a man, and educated, and an official,” said Grandmother, “and I am only a stupid old woman.

Why don’t you pick the one that will give me the best rate of exchange for Hungarian currency?”

When he had stamped one passport and she had safely stowed all four of them back into her shopping bag, she said:

“You are such an intelligent young man; please get my bags and take them through customs for me.

I can’t lift them myself and,” nodding at me, “I have this boy to look after, to make sure he does his piano exercises.”

And the surly, supercilious clerk obeyed.

As the twenties wore on, Austria steadily drifted toward civil war.

The Socialists held the only big city, Vienna, with an unshakable majority.

The Catholic Conservatives held the rest of the country with an equally unshakable majority.

Neither side would give an inch.

Instead both built up private armies, brought in weapons from abroad, and prepared for a showdown.

By 1927 everybody knew it was imminent, and indeed everybody knew the fighting would start at a demonstration at the conclusion of some long, drawn-out legal trial.

The only question, apparently, was who would shoot first—which only depended on which side lost the lawsuit and took to the streets in protest.

When it was announced that the Supreme Court would hand down its verdict on a certain day, everybody got off the street, went home, and locked the door—everybody, that is, except Grandmother.

She sallied forth on her usual rounds.

But when she passed by the University—a block or two from her apartment house—she saw something unusual on the building’s flat roof.

As it was the middle of the summer vacation, the doors were locked.

But Grandmother knew, of course, where the back door was and how to get to the back stairs.

She climbed up all six or seven stories, umbrella and shopping bag in hand, until she came out on the roof.

And there was a battalion of soldiers in battle-dress with guns trained on the Parliament Square just below.

(The precautions were not altogether frivolous.

Riots started a few hours later.

The mob burned down the law courts and tried to set fire to the Parliament Building, and there was heavy fighting all over Vienna for another week or so.)

But Grandmother went straight up to the commanding officer and said, “Get those idiots out of here double-quick, and their guns with them.

They might hurt somebody.”

The last time I saw Grandmother, already in the early 1930s, a big pimply youth with a large swastika on his lapel boarded the streetcar in which I was taking Grandmother to spend Christmas with us.

Grandmother got up from her seat, inched up to him, poked him sharply in the ribs with her umbrella, and said, “I don’t care what your politics are; I might even share some of them.

But you look like an intelligent, educated young man.

Don’t you know this thing”—and she pointed to the swastika—“might give offense to some people?

It isn’t good manners to offend anyone’s religion, just as it isn’t good manners to make fun of acne.

You wouldn’t want to be called a pimply lout, would you?”

I held my breath.

By that time, swastikas were no laughing matter; and young men who wore them on the street were trained to kick an old woman’s teeth in without compunction.

But the lout meekly took his swastika off, put it in his pocket, and when he left the streetcar a few stops later, doffed his cap to Grandmother.

The whole family was aghast at the risk she had run.

Yet everybody also roared with laughter at her naïveté, her ignorance, her stupidity.

“Nazism just a form of acne, ha-ha-ha-ho-ho-ho,” roared her niece’s husband, Robert—the one who, as Undersecretary of War, had ordered the battalion onto the roof of the University and who had not been a bit amused when he heard of what he called “Grandmother’s feeble-minded interference with law and order.”

And “ha-ha-ha-ho-ho-ho” roared my father, who was then trying unsuccessfully to have the Nazi Party outlawed in Austria; “if only we could have Grandmother ride all streetcars, all the time.”

And “ha-ha-ha-ho-ho-ho” roared the (former) husband of a niece—she had died—who was suspected of having Nazi sympathies, or at least of making a very good thing out of stamping swastikas in his metalworking plant:

“Grandmother thinks politics is a finishing school!”

I laughed too, just as hard as the others.

But it was then that I first began to wonder about Grandmother’s reputation as the family moron.

It wasn’t only that her stupidity worked.

She did get through the postwar boundaries without having to stand in line for days on end; she made the grocer reduce his prices; and she got the lout to take off his swastika.

Yet that, I reflected, might still be stupidity, for as an old Latin tag has it, even the gods fight in vain against stupidity.

But I had been arguing with Nazis for years and never seen the slightest results.

Facts, figures, rational argument—nothing availed.

Here was Grandmother appealing to manners, and it worked.

Of course I knew the lout had put back the swastika as soon as he was out of Grandmother’s sight.

But for a moment he might have felt a little bit ashamed or at least embarrassed.

Grandmother was not “bright,” of course.

She was not an intellectual.

She was simple-minded and literal.

She read little, and her tastes ran to gothic tales rather than “serious” books.

She was shrewd in a way, not a bit clever.

Yet, as I came to suspect slowly, maybe she had wisdom rather than sophistication or cleverness or intelligence.

Of course she was funny.

But what if she were also right?

To approve or disapprove of the twentieth century would never have occurred to her—that was beyond a “stupid old woman.”

Yet she intuitively understood it long before anyone else.

She understood that in an age in which papers mean more than people, one can never have too many papers.

What papers one has does indeed determine the rate of exchange when currencies are controlled.

When bureaucrats get power, “public servants” become public masters, as Grandmother knew intuitively, unless they are made to serve the real “public,” that is, the individual.

And the one compelling argument against guns is, of course, that they hurt people.

We thought it very funny that Grandmother did not understand money and inflation.

But we have learned since that no one really understands them, least of all the economists perhaps.

Trying to relate everything to the one stable currency Grandmother had known, even though it was past history, is no longer quite so funny.

When the Securities and Exchange Commission prescribes “inflation accounting” for businesses, it does exactly what Grandmother tried to do in her primitive way; we “index” wages, pensions, and taxes, and express revenues and expenditures in “constant dollars.”

Grandmother had sensed a basic problem of the twentieth century:

if money is money, it must be the standard of value.

But if government can manipulate the standard at will, what then is money?

The price of eggs in 1892 Kreuzer is not the measure of all value, yet it may be better than no measure at all.

To approve or disapprove of the status of women or of the relationship between the sexes would never have occurred to Grandmother—that was beyond a “stupid old woman.”

But she knew that it was a man’s world and that women needed to be prepared for it, even though all they could do was put on clean underwear before sallying forth into a world that had little pity on them.

She did not have much use for the things men took seriously.

When her husband started talking economics or politics at the dinner table, Grandmother, I was told by my mother, would say, “Stock Exchange—if you gentlemen want to discuss things like Stock Exchange at the dinner table, you’d better do it without me,” and would get up and leave.

But she accepted that men are needed and that one has to put up with them—with their having stupid affairs with every stupid woman who makes eyes at them, with their not practicing the piano unless one sits with them (and I suspect that the piano was more important to Grandmother than sex, marriage, or mistresses), and that they made the rules, which a “stupid old woman” could then manipulate without too much difficulty.

What these bright nieces and grandchildren and sons-in-law and nephews of hers—and the shopkeepers as well—saw as proof of her being a moron, though a lovable one, was that Grandmother believed in and practiced basic values.

And she tried to inject them into the twentieth century, or at least into her sphere within it.

A wedding was a serious affair; one could not just shrug it off.

Maybe the marriage would turn out disastrously—Grandmother would not have been surprised.

But on that one day of the wedding, bride and groom were entitled to be feted, to be made much of, to be taken seriously.

One could not, of course, disregard the conflicting demand of a modern age “to confine oneself in a telegram to the utmost brevity,” but one must explain this before sending the perfunctory greeting.

The term “bourgeois” in its contemporary, and especially its English, meaning does not fit Grandmother.

She belonged to the earlier Age of the Burgher, the age that preceded the commercial and industrial and business civilization of the “Stock Exchange” to which she would never listen.

Her ancestors had for generations been silk weavers and silk dyers and ultimately silk merchants—originally probably from Flanders or Holland, then settled in Paisley near Glasgow when it emerged as the great textile center in the seventeenth century.

Ultimately, in the 1750s, they had been recruited to come to Vienna, to the new Imperial Austrian Silk Manufactory.

Theirs was a world of skilled craftsmen, of responsible guild members; a small world but one of concern and community, workmanship and self-respect.

There were no riches in that world, but modest self-reliance.

“I am but a stupid old woman” echoed the self-limitation of the skilled craftsman who did not envy the great ones of this world and never dreamed of joining their ranks; who knew himself to be as good as they, and better at his trade.

It was a world that respected work and the worker.

The poor prostitute forced to sell her body to get enough to eat was an object of pity; but she was entitled to be treated with courtesy.

The starlet who used her body to get acting roles and publicity and a rich husband—as Mimi ultimately succeeded in doing—deserved only contempt and had no “glamour.”

The waitress who did not respect her job enough to do it well was going to be unhappy—it was for her sake, not for that of the customers, that she should be forced to learn manners.

And however laughable Grandmother’s approach to the Nazi swastika, there was wisdom in it too.

Abandoning respect for the individual, his creed, his convictions, and his feelings, is the first step on the road to the gas chamber.

Above all, what that parochial, narrow-minded, comical old woman knew was that community is not distribution of income and social services and the miracles of modern medicine.

It is concern for the person.

It is remembering that the engineering nephew is the apple of Miss Olga’s eye, and rejoicing with that dried-up spinster when he passes his examination and gets his degree.

It is going out to some remote suburb to visit the whining “Little Paula” whom a long-dead family servant had raised and loved.

It is dragging arthritic joints up five flights of stairs and down five flights of stairs to bring cough drops to an old whore who has become a neighbor by soliciting men on the nearby street corner for years.

This world of the burgher and his community was small and narrow, short-sighted and stifling.

It smelled of drains and drowned in its own gossip.

Ideas counted for nothing and new ones were rejected out of hand.

There was exploitation in it and greed, and women suffered.

Like Grandmother’s silly feud over the apartment, it could be petty and rancorous.

But the values it had—respect for work and workmanship, and concern by the person for the person, the values that make a community—are precisely the values the twentieth century lacks and needs.

Without them it is neither “bourgeois” nor “Socialist”; it is “lumpen proletariat,” like the young lout with the swastika.

But what about those “Handles without Cups” and “Cups without Handles”?

How do they fit into the twentieth century, and what do they have to tell us?

I must admit that I could not fit them in for a long time.

Then ultimately, around 1955 or so, it dawned on me:

Grandmother had had a premonition of genius!

In her primitive and unsophisticated way, she had written the first computer program.

Indeed her kitchen cabinet, with its full classification of the unnecessary and unusable, is the only “total information system” I have seen to this day.

Grandmother died as she had lived—creating a “Grandmother story.”

Running around as usual in every kind of weather, she stepped off the curb in a heavy rainstorm directly in the path of an oncoming car.

The driver managed to swerve around her but she fell.

He stopped the car and rushed to help her up.

She was unhurt but obviously badly shaken.

“May I take you to a hospital?” the driver said.

“I think a doctor should look at you.”

“Young man, you are very kind to a stupid old woman,” Grandmother said.

“But maybe you’d better call an ambulance.

It might compromise you having a strange woman in your car—you know how people talk.”

When the ambulance came, ten minutes later, Grandmother was dead of a massive coronary.

Knowing how fond I had been of her, my brother phoned me to give me the news.

He began in a somber tone:

“I have something very sad to tell you:

Grandmother died earlier this morning.”

But when he began to tell me about her death, I heard a change come into his voice.

Then he started to laugh.

“Imagine.

Only Grandmother could say that—a woman in her seventies compromising a young man by being in a car with him!”

I laughed too.

Then it occurred to me:

a living seventy-five year old woman doesn’t compromise a young man—but how would he have explained an unknown old woman dead in his car?

Hemme and Genia

I owe to Hemme and Genia that I did not become a novelist.

I knew fairly early in my life that writing was one thing I was likely to do well—perhaps the only one.

It certainly was one thing I was willing to work on.

And the novel has all along been to me the test of the writer.

I was always more interested in people than in abstractions, let alone in the categorical straitjackets of the philosopher.

People are to me not only more interesting and more varied but more meaningful precisely because they develop, unfold, change, and become.

And I knew early that Hemme and Genia—or, to give them their full names, Dr. Hermann Schwarzwald and his wife, Dr. Eugenia Schwarzwald née Nussbaum—were the most interesting people I was ever likely to meet.

If I was to write stories, they would have to be in them.

Yet I also knew early that I was unlikely to succeed in making believable, living characters out of Hemme and Genia.

Their foibles would be easy.

But their characters and personalities were far too shimmering, too ambivalent, too complex.

They attracted and fascinated me endlessly; they also disturbed, repulsed, and bothered me.

And whenever I tried to embrace them I embraced empty air.

At first glance there was nothing so very difficult or complex about Hemme or Genia, the prodigy civil servant and the prodigy woman educator.

Even their life stories differed from those of many others of their generation only by their greater, or at least earlier, worldly success.

Hemme was all bone and sharp angles.

He was completely bald, had been apparently since student days, with a pointed shiny bony knob at the top of the head, with bony ridges above deep-set eyes, bony pointed ears, and a sharp out-thrust chin.

He had long bony hands with big knuckles and big wrists protruding from coat sleeves that always appeared much too short.

He was of medium height and powerfully built, though lean as a scarecrow.

His mouth was tiny, prim, with narrow lips, usually clamped tightly shut.

His speech was a high-pitched bark and came out in short staccato bursts.

He said very little, and then usually something unpleasant.

My mother once came back from a trip to Paris with a wondrously fashionable dress, bought at high cost from one of the great couturiers.

She was very proud of it and saved it for the first big occasion—a reception at the Schwarzwalds’, perhaps the Christmas party, since children were invited too.

Hemme took one look at my mother and said:

“Go back home, Caroline, and take off that dress.

Give it to your maid—it looks as if you had borrowed it from her.”

And my mother—my strong-willed, argumentative, independent mother—went back home, took off the dress, and gave it to the maid.

Yet she was one of Hemme’s great favorites among the young women he called “Genia’s children.”

This angular, biting, bony man also was capable—though rarely—of great intuitive kindness.

Totally encapsulated in his own shell, he still sensed when to say the redeeming word, and what it had to be—and forced himself to say it.

I was in my mid-twenties and had long left Vienna when I came back to spend Christmas 1933 with my parents.

The spring before, when Hitler came to power, I had left Germany, gone to London, and found a job of sorts as “trainee” in a big insurance company for a few months.

But the job had come to an end by Christmas, I had no other and no prospect of one, and was deeply discouraged.

I knew I was not going to move back to Vienna—I had known since I was fourteen that I was not going to live there and had left at the earliest moment, when I finished high school.

I had also met in London a young woman—later to become my wife—and with every day away from her it became more apparent to me that I wanted to be with her and had to be where she was.

Still, I was being lulled into inertia by the comfort and ease of life at home, and I was besieged on all sides with arguments for staying and offers of cushy jobs—as a press officer in the Austrian Foreign Office, for instance.

I knew perfectly well that I did not want to stay, but I lingered.

Finally around early February I made up my mind to leave—eventually.

And so I began to postpone my departure by making farewell calls, among them to the Schwarzwalds.

Genia was kind and sympathetic and asked all sorts of questions about my job prospects in London (dismal), my finances (even more dismal), and the well-paid jobs and their opportunities that Vienna seemed to offer.

Suddenly Hemme came in, listened for a few seconds, and then spoke sharply—something he had never done to Genia in my hearing before:

“Lay off the lad, Genia.

Don’t act the foolish old woman!”

And turning to me, he said:

“I’ve known you since you were born.

I have always liked your willingness to go it alone and your refusal to run with the crowd, even with ours.

I was proud of you when you decided to leave Vienna and make your own career abroad as soon as you finished high school.

I was proud of you last year when you decided to quit Germany when the Nazis came in.

And you’re right not to stay in Vienna—it’s yesterday and finished.

But, Peter,” he continued, “once one decides to leave, one leaves; one doesn’t make farewell calls.

Kiss Genia goodbye, get up”—and he pulled me out of the chair—“go home and pack.

The train for London leaves tomorrow at noon and you are going to be on it.”

Roughly and with considerable force he dragged me out the door and pushed me down the stairs.

When he saw that I had reached the bottom and was making for the front door, he shouted, “Don’t worry about getting a job—there always are jobs, and better ones than you’d find here.

When you have it, drop us a postcard—and don’t altogether forget us.”

I did leave, on the noon train the next day.

I got a job within six hours after arriving in London—and an infinitely better one than any Vienna could possibly have offered—as economist to a London merchant bank and executive secretary to the partners.

And I did send Hemme the postcard he had asked for.

But I knew that I owed him more—much more—and I sensed what helping me must have cost that retiring, withdrawn man.

I did want to write him a warm letter.

But I was afraid of being laughed at for being sentimental and didn’t write it.

I have never forgiven myself.

For I never saw Hemme again, never could tell him.

I did indeed revisit Vienna every Christmas until my wife and I moved to New York, three years later.

And I did then call on Genia each time.

But Hemme could not be seen on any of these visits.

He suffered a stroke the summer of 1934, recovered fully physically but became senile mentally.

He had lucid days, many of them, apparently, but never when I chanced to be there.

I was told years later that he would often during these lucid, or half-lucid, days ask:

“Why haven’t I heard from Peter Drucker?”

Adults tended to be afraid of Hemme, resentful of his bitter, biting tongue and put off by his refusal to let anyone come close.

He was just as rough with children—indeed he treated small children exactly the way he treated everyone.

For this reason, perhaps, they adored him and were totally unafraid of him.

Even in his later years he was always surrounded by seven or eight year olds, at whom he barked and who barked right back.

Yet he had the one physical characteristic that frightens small children, for Hemme Schwarzwald was a cripple.

One leg was much shorter than the other and ended in a grossly deformed clubfoot.

The hip twisted to the outside so that the thigh stood at a sharp angle to the body.

Then, below the knee, the leg twisted sharply back in again.

Without his cane Hemme could not move at all; and with the cane he could only slither, almost crabwise.

Stairs and slopes were difficult for him, although he managed and refused all offers of help.

On level ground, however, he moved so fast that even sturdy young men had a hard time keeping up with his loping shuffle.

According to rumor, Hemme’s deformity was the result of an early childhood accident.

He had been dropped in infancy, some said; he had fallen out of a window, said others; the most popular version had young Hemme in the way of a runaway horse or thrown by one.

Hemme himself never mentioned his handicap.

But then he never mentioned anything about his childhood, his family, or his early life.

It was well known that he had been born, the youngest of several sons, around 1870 or a few years earlier in the easternmost part of Austrian Poland, just a few miles from the Russian border.

The family was dirt-poor, living at the margin of subsistence—the father was said to have been a shiftless peddler whose wife supported him by working as a midwife.

But the family had already made the big step toward assimilation into the successful bourgeoisie.

An uncle—the mother’s brother—had moved to Vienna and become one of the city’s leading lawyers and the first Jew to head the Vienna Bar Association.

The uncle had no children of his own and undertook to look after his nephews, especially young Hemme, who showed intellectual brilliance and high promise at an early age.

He put the nephews through secondary school.

Hemme’s next brother then moved to Vienna and went to the University as his uncle’s guest—he later became a respected lower court judge in Vienna.

So when Hemme, a year or two later, graduated from the local Gymnasium two years ahead of his age group, everyone including the uncle expected him to follow his brother.

Hemme cannot have been more than seventeen then.

But both his gift for doing the unexpected and inexplicable and his willpower had matured.

He refused to go to Vienna; he chose the University of Czernowitz instead.

Czernowitz was the German-speaking university of Austrian Poland (of the two others, Krakow spoke Polish and Lemberg, or Lwow, Ukrainian).

And this meant, of course, that its student body was solidly Jewish—only Jews in Austrian Poland spoke German (or Yiddish).

But even Polish Jewish boys did not go to Czernowitz unless they absolutely had to.

They scrounged and finagled to make it to a university in “the West,” such as Vienna or Prague.

For while a fully accredited state university, Czernowitz was unacceptable socially and hardly the right place to launch a career.

In some ways Czernowitz’s position in Austria-Hungary was similar to New York’s City College in American academia during the 1920s and 1930s:

renowned for the competitive ardor of its students, but shunned by anyone who had the chance to go anyplace else.

When Hemme announced his decision to go to Czernowitz, the pressures on him to change his mind were tremendous.

The uncle—or so my father, who got to know the uncle quite well, once told me—offered to rent a separate room for the young man if only he would come to Vienna.

He offered to pay for a long study trip to Germany, Switzerland, France, and England—the dream of every young Austrian.

He even threatened to withdraw his financial support.

But Hemme stood his ground and went to Czernowitz.

He graduated first in his law-school class and in record time.

Now he was ready to move to Vienna.

The uncle pulled all the strings to get him the best government job Austria could offer a young law-school graduate (especially one who was Jewish rather than a son of the landed aristocracy):

a position in the counsel’s office of the Ministry of Finance.

Yes, Hemme answered, he had decided to enter the civil service, but not in the Ministry of Finance.

He was entering the Department of Foreign Trade.

If choosing Czernowitz rather than Vienna was the whim of a boy, turning down the Ministry of Finance in favor of the Department of Foreign Trade was both folly and deliberate manifesto.

To be sure, the Department of Foreign Trade was the oldest of Austrian government agencies, having been founded in the mid-eighteenth century before any of the “modern” nineteenth-century ministries.

It still bore the quaint name the eighteenth century had given it, being known as the “Commercial Museum,” since it had been founded originally to promote Austria’s export trade through permanent and traveling trade fairs.

It was autonomous, though precariously balanced between Foreign Office and Ministry of Economics.

It ran and controlled the consular service, independently of, and often in competition with, the diplomatic service.

The Commercial Museum also operated two institutions of university status, the Oriental Academy and the Consular Academy; and soon after Hemme joined it, it started the first university-level business school in Austria, the present Vienna University of World Trade, originally called the “Export Academy.”

It was thus an interesting place and full of interesting people.

But it had no prestige and offered no opportunities.

It was a backwater.

The Ministry of Finance, by contrast—and especially its counsel’s office—practically controlled the top positions in Austria’s government and in the top rungs of Austrian business, or at least those that were open to non-aristocrats since the other three “prestige” ministries, Agriculture, Interior, and Foreign, were by and large reserved for barons and counts.

Those officials in the counsel’s office who did not get to the top in Finance moved into the senior positions in the prime minister’s office, into the top jobs in the “lesser” ministries, such as Commerce and Justice, or into the chairmanships of the major banks.

But worse than folly, choosing Foreign Trade over Finance was a political manifesto.

Finance was the official “liberal.”

Educated, tolerant, judicious, it was, so to speak, the “loyal opposition” in a heavily conservative Austrian establishment.

But the Department of Foreign Trade was “subversive.”

Austria was protectionist; Foreign Trade was avowedly free-trade.

Austria was primarily agricultural; Foreign Trade industrialized.

Trade unions were, of course, frowned upon officially if not suppressed by the police.

But Foreign Trade believed in them, encouraged the workers’ university-level courses started by the unions and furnished teachers for them.

It preached industrial safety, child labor laws, and a shorter work week.

Worst of all, from its inception as a child of Austrian Enlightenment in the eighteenth century, the Department of Foreign Trade had had close though surreptitious ties to Austrian Freemasonry—and Freemasonry in Austria was always political rather than social or philanthropic, even when the Vienna Grand Lodge was headed by an emperor as it was in the eighteenth century.

Freemasonry was anti-clerical if not anti-Catholic, opposed to big landholders and big landholdings, and above all, deeply anti-military.

Whether this subversive element was tolerated within the bosom of government because Austria was tolerant or because it was disorganized, I leave to the historians.

But it was only tolerated.

To join Foreign Trade, especially when one had the choice to go to Finance, was worse than being eccentric; it was a slap in everybody’s face—and clearly meant as such.

Hemme, it soon transpired, did not even decide for Foreign Trade over Finance out of conviction, as my father did for instance, about ten years later, and as most of the officials in Foreign Trade had done.

He went to Foreign Trade to break with his family once and for all, and in a way most calculated to hurt them.

The solicitous uncle not only got Hemme the Finance Ministry job.

He sent him a first-class railway ticket—at that time in the early 1890s only generals and bank directors traveled in such luxury.

And since the young man had never been in a big city, the uncle went down to the railroad station at an ungodly morning hour to meet him after the long trip from the Eastern provinces.

He was shocked by the young man’s deformity—he had, of course, known about it but had not realized how bad it was.

But he was pleased when the nephew asked how far it was to the uncle’s apartment and then suggested that they might walk in the early sun of a lovely spring morning.

That, thought the uncle, would give him a chance to tell all about the job he had lined up for him, the living arrangements—he had invited the young man to stay with him, but tactfully offered to put him up in a nearby hotel should he prefer to be alone—and the important and influential people to whom the brilliant nephew had already been introduced by name.

He was somewhat disconcerted that the young man did not say one word the whole way during a walk of over an hour.

But finally when they came to the quiet residential street in which the uncle and aunt had their apartment, the nephew asked to be excused for a few minutes.

“I thought to myself,” recounted the uncle:

“How nice.

He is going to get some flowers for an aunt he has never seen and with whom he is going to live for some time.”

An hour went by—and no nephew—then two hours, three, four.

Finally in mid-afternoon when the aunt was in hysterics and the uncle ready to call the police, a messenger arrived with a note:

“I have accepted a position with the Commercial Museum; please hand bearer of this my trunk.”

That was the last the uncle and aunt ever heard or saw of Hemme.

When, during the first years, these good people invited him—for New Year’s, for holidays, or for a weekend—their letters were returned unopened.

Nor did Hemme call on his brother or respond to his letters or calls.

This may be called eccentric; ultimately it degenerated into what can only be called contemptible.

Some ten years after Hemme had moved to Vienna, Hemme’s mother died and his father, the incompetent peddler, gave up.

Uncle thereupon brought the father to Vienna and procured a sinecure for him, the monopoly on peddling in the building of the Ministry of Finance.

Officially, of course, peddlers were strictly forbidden in government buildings.

But actually there was always one who, by purchase or influence, was allowed the free run of the building where he peddled small items from ties to razor blades, ran errands for civil servants such as getting a corsage or theater tickets when the younger ones went out on a date, or a picnic hamper when the older ones took their families out for a Saturday afternoon, went down to the store to buy stationery against a 10 percent discount and, in general, supplied the large bureaucracy with small needs and amenities.

This “in-house peddler” was by no means an Austrian specialty.

He can be found in the English government departments of Trollope’s novels of the 1850s, and in stories of Bismarck’s Germany.

He was still very much alive in the office buildings of New York in the 1930s and 1940s—each of which had a shoeshine “boy” with a secure turf of his own, a vendor of ties, shirts, notions, and so on; perhaps they still have them, for aught I know.

The inhouse peddler was considered a kind of upper servant and his social position was not very high.

But it was higher, and certainly more secure, than that of a small shopkeeper.

There was no competition and, above all, the in-house peddler did not “degrade” himself by running an “open store.”

So old man Schwarzwald was at least guaranteed a modest living and a job he could hold.

Then Hemme moved to the Ministry of Finance.

His first act was to order the old man thrown out; and when the father pleaded for an interview with his son, Hemme refused to see him.

Alfred Adler, Freud’s erstwhile disciple and later rival, who knew Hemme well, considered this story a classical example of “overcompensation” for a debilitating physical deformity.

He was convinced that Hemme blamed his parents, if only subconsciously, for being a cripple.

But the behavior toward his family was by no means Hemme’s only “eccentricity.”

He had chosen the Department of Foreign Trade over the Ministry of Finance.

Yet he had no use for the department’s basic policies and convictions.

On the contrary.

The department believed in free trade.

Hemme did not believe in trade at all, and would permit it only if completely controlled.

The department believed in industrialization, if only to find jobs for a rapidly growing population.

Hemme was an agrarian; and he would have exposed babies to prevent population growth.

The department had been created to help merchants.

Hemme despised merchants and all middlemen, considering them parasites.

Altogether his ideal was the China of the Mandarins; and the only thing he ever wrote was an encomium on Chinese bimetallism.

For Hemme also totally repudiated the gold standard and the economic theory of his day.

In retrospect it is clear that he was a Keynesian forty years before Keynes, believing in demand management where the received wisdom did not believe in political management of the economy at all, or only in management of supply; in government manipulation of currency, credit, and money where the received wisdom considered such manipulation to be both futile and self-defeating; and in creating consumer purchasing power as the cure for most economic ills.

Only neither the theoretical tools nor the data for such revolutionary theories were available in 1890—and anyhow Hemme was a prophet who talked in tongues rather than a systematic thinker.

But again in his economics there was the strange twist, the quirk that had showed in the way he treated his father.

For Hemme had a hero in economics—and his name was Eugen Dühring.

If Dühring is known to economic history at all, it is as the target of Friedrich Engels’s powerful attack on him, the Anti-Dühring which is one of the canonical books of Marxism.

One need not be convinced of Engels’s position after reading this book.

But for everyone who has ever read the book, Dühring is finished—for everyone, that is, except Hemme Schwarzwald.

Reading the book as a student in Czernowitz, he became a lifelong admirer of Dühring’s.

Until World War I he journeyed every year to Jena, the small German university where his hero is buried, to deposit a wreath on his grave.

But what attracted Hemme was not the man’s economics—Hemme had much too good a mind not to know Dühring to be thoroughly muddle-headed.

What attracted him was that Dühring alone among all known nineteenth-century economists had been ardently, indeed violently, anti-Jewish.

Of course this was long before Hitler, when being anti-Jewish was not seen as necessarily having practical consequences.

Also Hemme was by no means the only European Jew who turned anti-Jewish to resolve his own inner conflicts.

Marx held very much the same opinions.

And both Freud in Vienna and Henri Bergson in France—Hemme’s contemporaries—could only come to terms with their own Jewish heritage by turning against it, Freud in Moses and Monotheism, one of his last major works.

Hemme also—unlike Marx—had no personal feelings about Jews.

His wife was Jewish.

His only truly close friend was the one among Viennese bankers—most of them Jewish in origin—who was a practicing orthodox Jew to the point where his son, a classmate of mine, was the only one among many Jews in the school who did not read, write, or recite on Saturdays; even the rabbi’s child, who was also in our class, did so.

And Hemme, of course, never pretended that he himself was of any but pure Jewish origin.

Still, he considered the Jew the source of all evil in the modern world and the poisoner of society through his bourgeois, acquisitive, rationalist spirit.

Only, being Jewish to him was not a matter of race or religion but of attitude and spirit.

And he himself, he knew, had sloughed off the Jew long ago and was as completely un-Jewish as one could be.

Anyone less likely to succeed in the tight, cliquish, and jealous world of Austrian officialdom than Hemme Schwarzwald is hard to imagine.

Abrasive, rude, tactless, obnoxious; from Czernowitz rather than from Vienna, and the Commercial Museum rather than the counsel’s office in the Ministry of Finance; married to an equally aggressive Jewish outsider; without money or family connections but with loudly voiced opinions on all and every subject that would have been considered laughable had they not been so offensive; and with a tongue that made enemies out of most of the people he encountered—he sounds almost like the anti-hero in one of Sholem Aleichem’s or Isaac Bashevis Singer’s tragi-comic stories of Jewish failure.

Hemme also did everything in his power to trip himself up.