|

… My work on innovation and entrepreneurship began thirty years ago, in the mid-fifties.

For two years, then, a small group met under my leadership at the Graduate Business School of New York University every week for a long evening’s seminar on Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

The group included people who were just launching their own new ventures, most of them successfully.

It included mid-career executives from a wide variety of established, mostly large organizations: two big hospitals; IBM and General Electric; one or two major banks; a brokerage house; magazine and book publishers; pharmaceuticals; a worldwide charitable organization; the Catholic Archdiocese of New York and the Presbyterian Church; and so on.

The concepts and ideas developed in this seminar were tested by its members week by week during those two years in their own work and their own institutions.

Since then they have been tested, validated, refined, and revised in more than twenty years of my own consulting work.

Again, a wide variety of institutions has been involved.

Some were businesses, including high-tech ones such as pharmaceuticals and computer companies; “no-tech” ones such as casualty insurance companies; “world-class” banks, both American and European; one-man startup ventures; regional wholesalers of building products; and Japanese multinationals.

But a host of “nonbusinesses” also were included: several major labor unions; major community organizations such as the Girl Scouts of the U.S.A. or C.A.R.E. , the international relief and development cooperative; quite a few hospitals; universities and research labs; and religious organizations from a diversity of denominations.

Because this book distills years of observation, study, and practice, I was able to use actual “mini-cases,” examples and illustrations both of the right and the wrong policies and practices.

Wherever the name of an institution is mentioned in the text, it has either never been a client of mine (e. g., IBM) and the story is in the public domain, or the institution itself has disclosed the story.

Otherwise organizations with whom I have worked remain anonymous, as has been my practice in all my management books.

But the cases themselves report actual events and deal with actual enterprises.

Only in the last few years have writers on management begun to pay much attention to innovation and entrepreneurship.

I have been discussing aspects of both in all my management books for decades.

Yet this is the first work that attempts to present the subject in its entirety and in systematic form.

This is surely a first book on a major topic rather than the last word—but I do hope it will be accepted as a seminal work.

Systematic Entrepreneurship

From Part I, Chapter 1 (above)

“The entrepreneur,” said the French economist J.B. Say around 1800, “shifts economic resources out of an area of lower and into an area of higher productivity and greater yield.”

But Say’s definition does not tell us who this “entrepreneur” is.

And since Say coined the term almost two hundred years ago, there has been total confusion over the definitions of “entrepreneur” and “entrepreneurship.”

In the United States, for instance, the entrepreneur is often defined as one who starts his own, new and small business.

Indeed, the courses in “Entrepreneurship” that have become popular of late in American business schools are the linear descendants of the course in starting one’s own small business that was offered thirty years ago, and in many cases, not very different.

But not every new small business is entrepreneurial or represents entrepreneurship.

The husband and wife who open another delicatessen store or another Mexican restaurant in the American suburb surely take a risk.

But are they entrepreneurs?

All they do is what has been done many times before.

They gamble on the increasing popularity of eating out in their area, but create neither a new satisfaction nor new consumer demand.

Seen under this perspective they are surely not entrepreneurs even though theirs is a new venture.

... snip, snip ...

Admittedly, all new small businesses have many factors in common.

But to be entrepreneurial, an enterprise has to have special characteristics over and above being new and small.

Indeed, entrepreneurs are a minority among new businesses.

They create something new, something different; they change or transmute values.

An enterprise also does not need to be small and new to be an entrepreneur.

Indeed, entrepreneurship is being practiced by large and often old enterprises.

The General Electric Company (G.E.), one of the world’s biggest businesses and more than a hundred years old, has a long history of starting new entrepreneurial businesses from scratch and raising them into sizable industries.

And G.E. has not confined itself to entrepreneurship in manufacturing.

Its financing arm, G.E. Credit Corporation, in large measure triggered the upheaval that is transforming the American financial system and is now spreading rapidly to Great Britain and western Europe as well.

G.E. Credit in the sixties ran around the Maginot Line of the financial world when it discovered that commercial paper could be used to finance industry.

This broke the banks’ traditional monopoly on commercial loans.

... snip, snip ...

Again, G.E. and Marks and Spencer have many things in common with large and established businesses that are totally unentrepreneurial.

What makes them “entrepreneurial” are specific characteristics other than size or growth.

... snip, snip ...

Finally, entrepreneurship is by no means confined solely to economic institutions.

No better text for a History of Entrepreneurship could be found than the creation and development of the modern university, and especially the modern American university.

The modern university as we know it started out as the invention of a German diplomat and civil servant, Wilhelm von Humboldt, who in 1809 conceived and founded the University of Berlin with two clear objectives: to take intellectual and scientific leadership away from the French and give it to the Germans; and to capture the energies released by the French Revolution and turn them against the French themselves, especially Napoleon.

... snip, snip ...

Whereas English speakers identify entrepreneurship with the new, small business, the Germans identify it with power and property, which is even more misleading.

The Unternehmer—the literal translation into German of Say’s entrepreneur—is the person who both owns and runs a business (the English term would be “owner-manager”).

And the word is used primarily to distinguish the “boss,” who also owns the business, from the “professional manager” and from “hired hands” altogether.

... snip, snip ...

But the first attempts to create systematic entrepreneurship—the entrepreneurial bank founded in France in 1857 by the Brothers Pereire in their Crédit Mobilier, then perfected in 1870 across the Rhine by Georg Siemens in his Deutsche Bank, and brought across the Atlantic to New York at about the same time by the young J.P. Morgan did not aim at ownership.

The task of the banker as entrepreneur was to mobilize other people’s money for allocation to areas of higher productivity and greater yield.

The earlier bankers, the Rothschilds, for example, became owners.

Whenever they built a railroad, they financed it with their own money.

The entrepreneurial banker, by contrast, never wanted to be an owner.

He made his money by selling to the general public the shares of the enterprises he had financed in their infancy.

And he got the money for his ventures by borrowing from the general public.

Nor are entrepreneurs capitalists, although of course they need capital as do all economic (and most noneconomic) activities.

They are not investors, either.

They take risks, of course, but so does anyone engaged in any kind of economic activity.

The essence of economic activity is the commitment of present resources to future expectations, and that means to uncertainty and risk.

The entrepreneur is also not an employer, but can be, and often is, an employee—or someone who works alone and entirely by himself or herself.

Entrepreneurship is thus a distinct feature whether of an individual or of an institution.

It is not a personality trait; in thirty years I have seen people of the most diverse personalities and temperaments perform well in entrepreneurial challenges.

To be sure, people who need certainty are unlikely to make good entrepreneurs.

But such people are unlikely to do well in a host of other activities as well in politics, for instance, or in command positions in a military service, or as the captain of an ocean liner.

In all such pursuits decisions have to be made, and the essence of any decision is uncertainty.

But everyone who can face up to decision making can learn to be an entrepreneur and to behave entrepreneurially.

Entrepreneurship, then, is behavior rather than personality trait.

And its foundation lies in concept and theory rather than in intuition.

Every practice rests on theory, even if the practitioners themselves are unaware of it.

Entrepreneurship rests on a theory of economy and society.

The theory sees change as normal and indeed as healthy.

And it sees the major task in society—and especially in the economy—as doing something different rather than doing better what is already being done.

This is basically what Say, two hundred years ago, meant when he coined the term entrepreneur.

It was intended as a manifesto and as a declaration of dissent: the entrepreneur upsets and disorganizes.

As Joseph Schumpeter formulated it, his task is “creative destruction.”

Say was an admirer of Adam Smith.

He translated Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776) into French and tirelessly propagated throughout his life Smith’s ideas and policies.

But his own contribution to economic thought, the concept of the entrepreneur and of entrepreneurship, is independent of classical economics and indeed incompatible with it.

Classical economics optimizes what already exists, as does mainstream economic theory to this day, including the Keynesians, the Friedmanites, and the Supply-siders.

It focuses on getting the most out of existing resources and aims at establishing equilibrium.

It cannot handle the entrepreneur but consigns him to the shadowy realm of “external forces,” together with climate and weather, government and politics, pestilence and war, but also technology.

What is technology?

The traditional economist, regardless of school or “ism,” does not deny, of course, that these external forces exist or that they matter.

But they are not part of his world, not accounted for in his model, his equations, or his predictions.

The Poverty of Economic Theory

And while Karl Marx had the keenest appreciation of technology—he was the first and is still one of the best historians of technology—he could not admit the entrepreneur and entrepreneurship into either his system or his economics.

Knowledge and technology

All economic change in Marx beyond the optimization of present resources, that is, the establishment of equilibrium, is the result of changes in property and power relationships, and hence “politics,” which places it outside the economic system itself.

Knowledge economy and knowledge polity

Joseph Schumpeter was the first major economist to go back to Say.

In his classic Die Theorie der Wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung (The Theory of Economic Dynamics), published in 1911, Schumpeter broke with traditional economics—far more radically than John Maynard Keynes was to do twenty years later.

He postulated that dynamic disequilibrium brought on by the innovating entrepreneur, rather than equilibrium and optimization, is the “norm” of a healthy economy and the central reality for economic theory and economic practice.

Say was primarily concerned with the economic sphere.

But his definition only calls for the resources to be “economic.”

The purpose to which these resources are dedicated need not be what is traditionally thought of as economic.

Education is not normally considered “economic”; and certainly economic criteria are hardly appropriate to determine the “yield” of education (though no one knows what other criteria might pertain).

But the resources of education are, of course, economic.

They are in fact identical with those used for the most unambiguously economic purpose such as making soap for sale.

Indeed, the resources for all social activities of human beings are the same and are “economic” resources: capital (that is, the resources withheld from current consumption and allocated instead to future expectations), physical resources, whether land, seed corn, copper, the classroom, or the hospital bed; labor, management, and time.

Hence entrepreneurship is by no means limited to the economic sphere although the term originated there.

It pertains to all activities of human beings other than those one might term “existential” rather than “social.”

And we now know that there is little difference between entrepreneurship whatever the sphere.

The entrepreneur in education and the entrepreneur in health care—both have been fertile fields—do very much the same things, use very much the same tools, and encounter very much the same problems as the entrepreneur in a business or a labor union.

Entrepreneurs see change as the norm and as healthy.

Usually, they do not bring about the change themselves.

But—and this defines entrepreneur and entrepreneurship—

the entrepreneur always

searches for change,

responds to it,

and exploits it as an opportunity.

Entrepreneurship is “risky” mainly because so few of the so-called entrepreneurs know what they are doing.

They lack the methodology.

They violate elementary and well-known rules.

This is particularly true of high-tech entrepreneurs.

To be sure (as will be discussed in Chapter 9), high-tech entrepreneurship and innovation are intrinsically more difficult and more risky than innovation based on economics and market structure, on demographics, or even on, something as seemingly nebulous and intangible as Weltanschauung—perceptions and moods.

But even high-tech entrepreneurship need not be “high-risk,” as Bell Lab and IBM prove.

It does need, however, to be systematic.

It needs to be managed.

Above all, it needs to be based on purposeful innovation (below).

Also see Entrepreneurs and Innovation from Managing in the Next Society by Peter Drucker plus my separate innovation and entrepreneurship topic pages

The memo THEY don’t want you to see

Entrepreneurs innovate.

Innovation is the specific instrument of entrepreneurship.

It is the act that endows resources with a new capacity to create wealth.

Innovation, indeed, creates a resource.

There is no such thing as a “resource” until man finds a use for something in nature and thus endows it with economic value.

Until then, every plant is a weed and every mineral just another rock.

Not much more than a century ago, neither mineral oil seeping out of the ground nor bauxite, the ore of aluminum, were resources.

They were nuisances; both render the soil infertile.

The penicillin mold was a pest, not a resource.

Bacteriologists went to great lengths to protect their bacterial cultures against contamination by it.

Then in the 1920s, a London doctor, Alexander Fleming, realized that this “pest” was exactly the bacterial killer bacteriologists had been looking for—and the penicillin mold became a valuable resource.

The same holds just as true in the social and economic spheres.

There is no greater resource in an economy than “purchasing power.”

But purchasing power is the creation of the innovating entrepreneur.

The American farmer had virtually no purchasing power in the early nineteenth century; he therefore could not buy farm machinery.

There were dozens of harvesting machines on the market, but however much he might have wanted them, the farmer could not pay for them.

Then one of the many harvesting-machine inventors, Cyrus McCormick, invented installment buying.

This enabled the farmer to pay for a harvesting machine out of his future earnings rather than out of past savings—and suddenly the farmer had “purchasing power” to buy farm equipment.

Equally, whatever changes the wealth-producing potential of already existing resources constitutes innovation.

There was not much new technology involved in the idea of moving a truck body off its wheels and onto a cargo vessel.

This “innovation,” the container, did not grow out of technology at all but out of a new perception of the “cargo vessel” as a materials-handling device rather than a “ship,” which meant that what really mattered was to make the time in port as short as possible.

But this humdrum innovation roughly quadrupled the productivity of the ocean-going freighter and probably saved shipping.

Without it, the tremendous expansion of world trade in the last forty years—the fastest growth in any major economic activity ever recorded—could not possibly have taken place.

What really made universal schooling possible—more so than the popular commitment to the value of education, the systematic training of teachers in schools of education, or pedagogic theory—was that lowly innovation, the textbook.

(The textbook was probably the invention of the great Czech educational reformer Johann Amos Comenius, who designed and used the first Latin primers in the mid-seventeenth century.)

Without the textbook, even a very good teacher cannot teach more than one or two children at a time; with it, even a pretty poor teacher can get a little learning into the heads of thirty or thirty-five students.

Innovation, as these examples show, does not have to be technical, does not indeed have to be a “thing” altogether.

Few technical innovations can compete in terms of impact with such social innovations as the newspaper or insurance.

Installment buying literally transforms economies.

Wherever introduced, it changes the economy from supply-driven to demand-driven, regardless almost of the productive level of the economy (which explains why installment buying is the first practice that any Marxist government coming to power immediately suppresses: as the Communists did in Czechoslovakia in 1948, and again in Cuba in 1959).

The hospital, in its modern form a social innovation of the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, has had greater impact on health care than many advances in medicine.

Management, that is, the “useful knowledge” that enables man for the first time to render productive people of different skills and knowledge working together in an “organization,” is an innovation of this century.

It has converted modern society into something brand new, something, by the way, for which we have neither political nor social theory: a society of organizations.

Books on economic history mention August Borsig as the first man to build steam locomotives in Germany.

But surely far more important was his innovation—against strenuous opposition from craft guilds, teachers, and government bureaucrats — of what to this day is the German system of factory organization and the foundation of Germany’s industrial strength.

It was Borsig who devised the idea of the Meister (Master), the highly skilled and highly respected senior worker who runs the shop with considerable autonomy; and the Lehrling System (apprenticeship system), which combines practical training (Lehre) on the job with schooling (Ausbildung) in the classroom.

And the twin inventions of modern government by Machiavelli in The Prince (1513) and of the modern national state by his early follower, Jean Bodin, sixty years later, have surely had more lasting impacts than most technologies.

One of the most interesting examples of social innovation and its importance can be seen in modern Japan.

From the time she opened her doors to the modern world in 1867, Japan has been consistently underrated by westerners, despite her successful defeats of China and then Russia in 1894 and 1905, respectively; despite Pearl Harbor; and despite her sudden emergence as an economic superpower and the toughest competitor in the world market of the 1970s and 1980s.

A major reason, perhaps the major one, is the prevailing belief that innovation has to do with things and is based on science or technology.

And the Japanese, so the common belief has held (in Japan as well as in the West, by the way), are not innovators but imitators.

For the Japanese have not, by and large, produced outstanding technical or scientific innovations.

Their success is based on social innovation.

When the Japanese, in the Meiji Restoration of 1867, most reluctantly opened their country to the world, it was to avoid the fates of India and nineteenth-century China, both of which were conquered, colonized, and “westernized” by the West.

The basic aim, in true Judo fashion, was to use the weapons of the West to hold the West at bay; and to remain Japanese.

This meant that social innovation was far more critical than steam locomotives or the telegraph.

And social innovation, in terms of the development of such institutions as schools and universities, a civil service, banks and labor relations, was far more difficult to achieve than building locomotives and telegraphs.

A locomotive that will pull a train from London to Liverpool will equally, without adaptation or change, pull a train from Tokyo to Osaka.

But the social institutions had to be at once quintessentially “Japanese” and yet “modern.”

They had to be run by Japanese and yet serve an economy that was “Western” and highly technical.

Technology can be imported at low cost and with a minimum of cultural risk.

Institutions, by contrast, need cultural roots to grow and to prosper.

The Japanese made a deliberate decision a hundred years ago to concentrate their resources on social innovations, and to imitate, import, and adapt technical innovations—with startling success.

Indeed, this policy may still be the right one for them.

For, as will be discussed in Chapter 17, what is sometimes half-facetiously called creative imitation is a perfectly respectable and often very successful entrepreneurial strategy.

Even if the Japanese now have to move beyond imitating, importing, and adapting other people’s technology and learn to undertake genuine technical innovation of their own, it might be prudent not to underrate them.

Scientific research is in itself a fairly recent “social innovation.”

And the Japanese, whenever they have had to do so in the past, have always shown tremendous capacity for such innovation.

Above all, they have shown a superior grasp of entrepreneurial strategies.

“Innovation,” then, is an economic or social rather than a technical term.

It can be defined the way J. B. Say defined entrepreneurship, as changing the yield of resources.

Or, as a modern economist would tend to do, it can be defined in demand terms rather than in supply terms, that is, as changing the value and satisfaction obtained from resources by the consumer.

Which of the two is more applicable depends, I would argue, on the specific case rather than on the theoretical model.

The shift from the integrated steel mill to the “mini-mill,” which starts with steel scrap rather than iron ore and ends with one final product (e. g., beams and rods, rather than raw steel that then has to be fabricated), is best described and analyzed in supply terms.

The end product, the end uses, and the customers are the same, though the costs are substantially lower.

And the same supply definition probably fits the container.

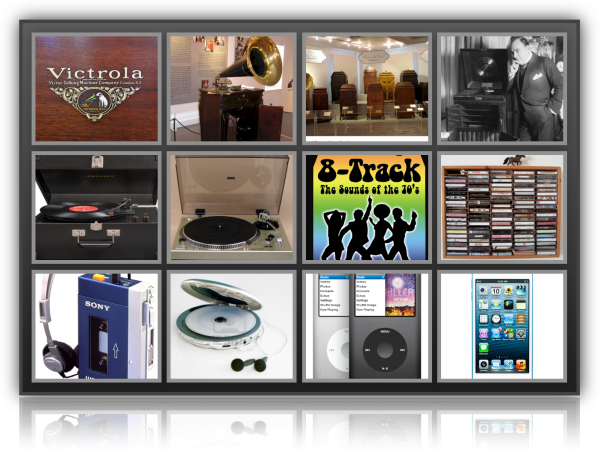

But the audiocassette or the videocassette, though equally “technical,” if not more so, are better described or analyzed in terms of consumer values and consumer satisfactions, as are such social innovations as the news magazines developed by Henry Luce of Time-Life-Fortune in the 1920s, or the money-market fund of the late 1970s and early 1980s.

We cannot yet develop a theory of innovation.

But we already know enough to say when, where, and how one looks systematically for innovative opportunities, and how one judges the chances for their success or the risks of their failure.

We know enough to develop, though still only in outline form, the practice of innovation.

It has become almost a cliché for historians of technology that one of the great achievements of the nineteenth century was the “invention of invention.”

Before 1880 or so, invention was mysterious; early nineteenth-century books talk incessantly of the “flash of genius.”

The inventor himself was a half-romantic, half-ridiculous figure, tinkering away in a lonely garret.

By 1914, the time World War I broke out, “invention” had become “research,” a systematic, purposeful activity, which is planned and organized with high predictability both of the results aimed at and likely to be achieved.

Something similar now has to be done with respect to innovation.

Entrepreneurs will have to learn to practice systematic innovation.

Successful entrepreneurs do not wait until “the Muse kisses them” and gives them a “bright idea”; they go to work.

Altogether, they do not look for the “biggie,” the innovation that will “revolutionize the industry,” create a “billion-dollar business,” or “make one rich overnight.”

Those entrepreneurs who start out with the idea that they’ll make it big—and in a hurry—can be guaranteed failure.

They are almost bound to do the wrong things.

An innovation that looks very big may turn out to be nothing but technical virtuosity; and innovations with modest intellectual pretensions, a McDonald’s, for instance, may turn into gigantic, highly profitable businesses.

The same applies to nonbusiness, public-service innovations.

Successful entrepreneurs, whatever their individual motivation—be it money, power, curiosity, or the desire for fame and recognition—try to create value and to make a contribution.

Still, successful entrepreneurs aim high.

They are not content simply to improve on what already exists, or to modify it.

They try to create new and different values and new and different satisfactions, to convert a “material” into a “resource,” or to combine existing resources in a new and more productive configuration.

And it is change that always provides the opportunity for the new and different.

Systematic innovation therefore consists in the purposeful and organized search for changes, and in the systematic analysis of the opportunities such changes might offer for economic or social innovation.

As a rule, these are changes that have already occurred or are under way.

The overwhelming majority of successful innovations exploit change.

To be sure, there are innovations that in themselves constitute a major change; some of the major technical innovations, such as the Wright Brothers’ airplane, are examples.

But these are exceptions, and fairly uncommon ones.

Most successful innovations are far more prosaic; they exploit change.

And thus the discipline of innovation (and it is the knowledge base of entrepreneurship) is a diagnostic discipline: a systematic examination of the areas of change that typically offer entrepreneurial opportunities.

Specifically, systematic innovation means monitoring seven sources for innovative opportunity.

The first four sources lie within the enterprise, whether business or public-service institution, or within an industry or service sector.

They are therefore visible primarily to people within that industry or service sector.

They are basically symptoms.

But they are highly reliable indicators of changes that have already happened or can be made to happen with little effort.

These four source areas are:

- The unexpected—the unexpected success, the unexpected failure, the unexpected outside event;

- The incongruity—between reality as it actually is and reality as it is assumed to be or as it "ought to be";

- Innovation based on process need;

- Changes in industry structure or market structure that catch everyone unawares.

The second set of sources for innovative opportunity, a set of three, involves changes outside the enterprise or industry:

- Demographics (population changes);

- Changes in perception, mood, and meaning;

- New knowledge, both scientific and nonscientific.

The lines between these seven source areas of innovative opportunities are blurred, and there is considerable overlap between them.

They can be likened to seven windows, each on a different side of the same building.

Each window shows some features that can also be seen from the window on either side of it.

But the view from the center of each is distinct and different.

The seven sources require separate analysis, for each has its own distinct characteristic.

No area is, however, inherently more important or more productive than the other.

Major innovations are as likely to come out of an analysis of symptoms of change (such as the unexpected success of what was considered an insignificant change in product or pricing) as they are to come out of the massive application of new knowledge resulting from a great scientific breakthrough.

But the order in which these sources will be discussed is not arbitrary.

They are listed in descending order of reliability and predictability.

For, contrary to almost universal belief, new knowledge—and especially new scientific knowledge—is not the most reliable or most predictable source of successful innovations.

For all the visibility, glamour, and importance of science-based innovation, it is actually the least reliable and least predictable one.

Conversely, the mundane and unglamorous analysis of such symptoms of underlying changes as the unexpected success or the unexpected failure carry fairly low risk and uncertainty.

And the innovations arising therefrom have, typically, the shortest lead time between the start of a venture and its measurable results, whether success or failure.

Innovation starting point

The Unexpected Success

No other area offers richer opportunities for successful innovation than the unexpected success.

In no other area are innovative opportunities less risky and their pursuit less arduous.

Yet the unexpected success is almost totally neglected; worse, managements tend actively to reject it.

Here is one example.

More than thirty years ago, I was told by the chairman of New York’s largest department store, R. H. Macy, “We don’t know how to stop the growth of appliance sales.”

“Why do you want to stop them?”

I asked, quite mystified.

“Are you losing money on them?”

“On the contrary,” the chairman said, “profit margins are better than on fashion goods; there are no returns, and practically no pilferage.”

“Do the appliance customers keep away the fashion customers?”

I asked.

“Oh, no,” was the answer.

“Where we used to sell appliances primarily to people who came in to buy fashions, we now sell fashions very often to people who come in to buy appliances.

But,” the chairman continued, “in this kind of store, it is normal and healthy for fashion to produce seventy percent of sales.

Appliance sales have grown so fast that they now account for three-fifths.

And that’s abnormal.

We’ve tried everything we know to make fashion grow to restore the normal ratio, but nothing works.

The only thing left now is to push appliance sales down to where they should be.”

For almost twenty years after this episode, Macy’s New York continued to drift.

Any number of explanations were given for Macy’s inability to exploit its dominant position in the New York retail market: the decay of the inner city, the poor economics of a store supposedly “too big,” and many others.

Actually, once a new management came in after 1970, reversed the emphasis, and accepted the contribution of appliances to sales, Macy’s—despite inner-city decay, despite its high labor costs, and despite its enormous size—promptly began to prosper again.

At the same time that Macy’s rejected the unexpected success, another New York retail store, Bloomingdale’s, used the identical unexpected success to propel itself into the number two spot in the New York market.

Bloomingdale’s, at best a weak number four, had been even more of a fashion store than Macy’s.

But when appliance sales began to climb in the early 1950s, Bloomingdale’s ran with the opportunity.

It realized that something unexpected was happening and analyzed it.

It then built a new position in the marketplace around its Housewares Department.

It also refocused its fashion and apparel sales to reach a new customer: the customer of whose emergence the explosion in appliance sales was only a symptom.

Macy’s is still number one in New York in volume.

But Bloomingdale’s has become the “smart New York store.”

And the stores that were the contenders for this title thirty years ago—the stores that were then strong number twos, the fashion leaders of 1950 such as Best—have disappeared (for additional examples, see Chapter 15).

The Macy’s story will be called extreme.

But the only uncommon aspect about it is that the chairman was aware of what he was doing.

Though not conscious of their folly, far too many managements act the way Macy’s did.

It is never easy for a management to accept the unexpected success.

It takes determination, specific policies, a willingness to look at reality, and the humility to say, “We were wrong!”

One reason why it is difficult for management to accept unexpected success is that all of us tend to believe that anything that has lasted a fair amount of time must be “normal” and go on “forever.”

Anything that contradicts what we have come to consider a law of nature is then rejected as unsound, unhealthy, and obviously abnormal.

This explains, for instance, why one of the major U.S. steel companies, around 1970, rejected the “minimill.”* (*On the ‘mini-mill,” see Chapter 4.)

Management knew that its steelworks were rapidly becoming obsolete and would need billions of dollars of investment to be modernized.

It also knew that it could not obtain the necessary sums.

A new, smaller “mini-mill” was the solution.

Almost by accident, such a “mini-mill” was acquired.

It soon began to grow rapidly and to generate cash and profits.

Some of the younger men within the steel company therefore proposed that the available investment funds be used to acquire additional “mini-mills” and to build new ones.

Within a few years, the “mini-mills” would then give the steel company several million tons of steel capacity based on modern technology, low labor costs, and pinpointed markets.

Top management indignantly vetoed the proposal; indeed, all the men who had been connected with it found themselves “ex-employees” within a few years.

“The integrated steelmaking process is the only right one,” top management argued.

“Everything else is cheating—a fad, unhealthy, and unlikely to endure.”

Needless to say, ten years later the only parts of the steel industry in America that were still healthy, growing, and reasonably prosperous were “mini-mills.”

To a steelmaker who has spent his entire life working to perfect the integrated steelmaking process, who is at home in the big steel mill, and who may himself be the son of a steelworker (as a great many American steel company executives have been), anything but “big steel” is strange and alien, indeed a threat.

It takes an effort to perceive in the “enemy” one’s own best opportunity.

Top management people in most organizations, whether small or large, public-service institution or business, have typically grown up in one function or one area.

To them, this is the area in which they feel comfortable.

When I sat down with the chairman of R. H. Macy, for instance, there was only one member of top management, the personnel vice-president, who had not started as a fashion buyer and made his career in the fashion end of the business.

Appliances, to these men, were something that other people dealt with.

The unexpected success can be galling.

Consider the company that has worked diligently on modifying and perfecting an old product, a product that has been the “flagship” of the company for years, the product that represents “quality.”

At the same time, most reluctantly, the company puts through what everyone in the firm knows is a perfectly meaningless modification of an old, obsolete, and “low-quality” product.

It is done only because one of the company’s leading salesmen lobbied for it, or because a good customer asked for it and could not be turned down.

But nobody expects it to sell; in fact, nobody wants it to sell.

And then this “dog” runs away with the market and even takes the sales which plans and forecasts had promised for the “prestige,” “quality” line.

No wonder that everybody is appalled and considers the success a “cuckoo in the nest” (a term I have heard more than once).

Everybody is likely to react precisely the way the chairman of R. H. Macy reacted when he saw the unwanted and unloved appliances overtake his beloved fashions, on which he himself had spent his working life and his energy.

The unexpected success is a challenge to management’s judgment.

“If the mini-mills were an opportunity, we surely would have seen it ourselves,” the chairman of the big steel company is quoted as saying when he turned the mini-mill proposal down.

Managements are paid for their judgment, but they are not being paid to be infallible.

In fact, they are being paid to realize and admit that they have been wrong especially when their admission opens up an opportunity.

But this is by no means common.

A Swiss pharmaceutical company today has world leadership in veterinary medicines, yet it has not itself developed a single veterinary drug.

But the companies that developed these medicines refused to serve the veterinary market.

The medicines, mostly antibiotics, were of course developed for treating human diseases.

When the veterinarians discovered that they were just as effective for animals and began to send in their orders, the original manufacturers were far from pleased.

In some cases they refused to supply the veterinarians; in many others, they disliked having to reformulate the drugs for animal use, to repackage them, and so on.

The medical director of a leading pharmaceutical company protested around 1953 that to apply a new antibiotic to the treatment of animals was a “misuse of a noble medicine.”

Consequently, when the Swiss approached this manufacturer and several others, they obtained licenses for veterinary use without any difficulty and at low cost.

Some of the manufacturers were only too happy to get rid of the embarrassing success.

Human medications have since come under price pressure and are carefully scrutinized by regulatory authorities.

This has made veterinary medications the most profitable segment of the pharmaceutical industry.

But the companies that developed the compounds in the first place are not the ones who get these profits.

Far more often, the unexpected success is simply not seen at all.

Nobody pays any attention to it.

Hence, nobody exploits it, with the inevitable result that the competitor runs with it and reaps the rewards.

A leading hospital supplier introduced a new line of instruments for biological and clinical tests.

The new products were doing quite well.

Then, suddenly, orders came in from industrial and university laboratories.

Nobody was told about them, nobody noticed them; nobody realized that, by pure accident, the company had developed products with more and better customers outside the market for which those products had been developed.

No salesman was being sent out to call on these new customers, no service force was being set up.

Five or eight years later, another company had taken over these new markets.

And because of the volume of business these markets produced, the newcomer could soon invade the hospital market offering lower prices and better services than the original market leader.

One reason for this blindness to the unexpected success is that our existing reporting systems do not as a rule report it, let alone clamor for management’s attention.

Practically every company—but every public-service institution as well—has a monthly or quarterly report.

The first sheet lists the areas in which performance is below expectations: it lists the problems and the shortfalls.

At the monthly meetings of the management group and the board of directors, everybody therefore focuses on the problem areas.

No one even looks at the areas where the company has done better than expected.

And if the unexpected success is not quantitative but qualitative—as in the case of the hospital instruments mentioned above, which opened up new major markets outside the company’s traditional ones—the figures will not even show the unexpected success as a rule.

To exploit the opportunity for innovation offered by unexpected success requires analysis.

Unexpected success is a symptom.

But a symptom of what?

The underlying phenomenon may be nothing more than a limitation on our own vision, knowledge, and understanding.

That the pharmaceutical companies, for instance, rejected the unexpected success of their new drugs in the animal market was a symptom of their own failure to know how big—and how important—livestock raising throughout the world is; of their blindness to the sharp increase in demand for animal proteins throughout the world after World War II, and to the tremendous changes in knowledge, sophistication, and management capacity of the world’s farmers.

The unexpected success of appliances at R. H. Macy’s was a symptom of a fundamental change in the behavior, expectations, and values of substantial numbers of consumers—as the people at Bloomingdale’s realized.

Up until World War II, department store consumers in the United States bought primarily by socioeconomic status, that is, by income group.

After World War II, the market increasingly segmented itself by what we now call “lifestyles.”

Bloomingdale’s was the first of the major department stores, especially on the East Coast, to realize this, to capitalize on it, and to innovate a new retail image.

The unexpected success of laboratory instruments designed for the hospital in industrial and university laboratories was a symptom of the disappearance of distinctions between the various users of scientific instruments, which for almost a century had created sharply different markets, with different end uses, specifications, and expectations.

What it symptomized—and the company never realized this—was not just that a product line had uses that were not originally envisaged.

It signaled the end of the specific market niche the company had enjoyed in the hospital market.

So the company that for thirty or forty years had successfully defined itself as a designer, maker, and marketer of hospital laboratory equipment was forced eventually to redefine itself as a maker of laboratory instruments, and to develop capabilities to design, manufacture, distribute, and service way beyond its original field.

By then, however, it had lost a large part of the market for good.

Thus the unexpected success is not just an opportunity for innovation; it demands innovation.

It forces us to ask, What basic changes are now appropriate for this organization in the way it defines its business?

Its technology?

Its markets?

If these questions are faced up to, then the unexpected success is likely to open up the most rewarding and least risky of all innovative opportunities.

Two of the world’s biggest businesses, DuPont, the world’s largest chemical company, and IBM, the giant of the computer industry, owe their preeminence to their willingness to exploit the unexpected success as an innovative opportunity.

DuPont, for 130 years, had confined itself to making munitions and explosives.

In the mid-1920s it then organized its first research efforts in other areas, one of them the brand-new field of polymer chemistry, which the Germans had pioneered during World War I.

For several years there were no results at all.

Then, in 1928, an assistant left a burner on over the weekend.

On Monday morning, Wallace H. Carothers, the chemist in charge, found that the stuff in the kettle had congealed into fibers.

It took another ten years before DuPont found out how to make Nylon intentionally.

The point of the story is, however, that the same accident had occurred several times in the laboratories of the big German chemical companies with the same results, and much earlier.

The Germans were, of course, looking for a polymerized fiber—and they could have had it, along with world leadership in the chemical industry, ten years before DuPont had Nylon.

But because they had not planned the experiment, they dismissed its results, poured out the accidentally produced fibers, and started all over again.

The history of IBM equally shows what paying attention to the unexpected success can do.

For IBM is largely the result of the willingness to exploit the unexpected success not once, but twice.

In the early 1930s, IBM almost went under.

It had spent its available money on designing the first electro-mechanical bookkeeping machine, meant for banks.

But American banks did not buy new equipment in the Depression days of the early thirties.

IBM even then had a policy of not laying off people, so it continued to manufacture the machines, which it had to put in storage.

When IBM was at its lowest point—so the story goes—Thomas Watson, Sr., the founder, found himself at a dinner party sitting next to a lady.

When she heard his name, she said: “Are you the Mr. Watson of IBM?

Why does your sales manager refuse to demonstrate your machine to me?”

What a lady would want with an accounting machine Thomas Watson could not possibly figure out, nor did it help him much when she told him she was the director of the New York Public Library; it turned out he had never been in a public library.

But next morning, he appeared there as soon as its doors opened.

In those days, libraries had fair amounts of government money.

Watson walked out two hours later with enough of an order to cover next month’s payroll.

And, as he added with a chuckle whenever he told the story, “I invented a new policy on the spot: we get cash in advance before we deliver.”

Fifteen years later, IBM had one of the early computers.

Like the other early American computers, the IBM computer was designed for scientific purposes only.

Indeed, IBM got into computer work largely because of Watson’s interest in astronomy.

And when first demonstrated in IBM’s show window on Madison Avenue, where it drew enormous crowds, IBM’s computer was programmed to calculate all past, present, and future phases of the moon.

But then businesses began to buy this “scientific marvel” for the most mundane of purposes, such as payroll.

Univac, which had the most advanced computer and the one most suitable for business uses, did not really want to “demean” its scientific miracle by supplying business.

But IBM, though equally surprised by the business demand for computers, responded immediately.

Indeed, it was willing to sacrifice its own computer design, which was not particularly suitable for accounting, and instead use what its rival and competitor (Univac) had developed.

Within four years IBM had attained leadership in the computer market, even though for another decade its own computers were technically inferior to those produced by Univac.

IBM was willing to satisfy business and to satisfy it on business’ terms—to train programmers for business, for instance.

Similarly, Japan’s foremost electronic company, Matsushita (better known by its brand names Panasonic and National), owes its rise to its willingness to run with unexpected success.

Matsushita was a fairly small and undistinguished company in the early 1950s, outranked on every count by such older and deeply entrenched giants as Toshiba or Hitachi.

Matsushita “knew,” as did every other Japanese manufacturer of the time, that “television would not grow fast in Japan.”

“Japan is much too poor to afford such a luxury,” the chairman of Toshiba had said at a New York meeting around 1954 or 1955.

Matsushita, however, was intelligent enough to accept that the Japanese farmers apparently did not know that they were too poor for television.

What they knew was that television offered them, for the first time, access to a big world.

They could not afford television sets, but they were prepared to buy them anyhow and pay for them.

Toshiba and Hitachi made better sets at the time, only they showed them on the Ginza in Tokyo and in the big-city department stores, making it pretty clear that farmers were not particularly welcome in such elegant surroundings.

Matsushita went to the farmers and sold its televisions door-to-door, something no one in Japan had ever done before for anything more expensive than cotton pants or aprons.

Of course, it is not enough to depend on accidents, nor to wait for the lady at the dinner table to express unexpected interest in one’s apparently failing product.

The search has to be organized.

The first thing is to ensure that the unexpected is being seen; indeed, that it clamors for attention.

It must be properly featured in the information management obtains and studies.

(How to do this is described in some detail in Chapter 13.)

Managements must look at every unexpected success with the questions:

(1) What would it mean to us if we exploited it?

(2) Where could it lead us?

(3) What would we have to do to convert it into an opportunity?

And (4) How do we go about it?

This means, first, that managements need to set aside specific time in which to discuss unexpected successes;

and second, that someone should always be designated to analyze an unexpected success and to think through how it could be exploited.

But management also needs to learn what the unexpected success demands of them.

Again, this might best be explained by an example.

A major university on the eastern seaboard of the United States started, in the early 1950s, an evening program of “continuing education” for adults, in which the normal undergraduate curriculum leading to an undergraduate degree was offered to adults with a high school diploma.

Nobody on the faculty really believed in the program.

The only reason it was offered at all was that a small number of returning World War II veterans had been forced to go to work before obtaining their undergraduate degrees and were clamoring for an opportunity to get the credits they still lacked.

To everybody’s surprise, however, the program proved immensely successful, with qualified students applying in large numbers.

And the students in the program actually outperformed the regular undergraduates.

This, in turn, created a dilemma.

To exploit the unexpected success, the university would have had to build a fairly big first-rate faculty.

But this would have weakened its main program; at the least, it would have diverted the university from what it saw as its main mission, the training of undergraduates.

The alternative was to close down the new program.

Either decision would have been a responsible one.

Instead, the university decided to staff the program with cheap, temporary faculty, mostly teaching assistants working on their own advanced degrees.

As a result, it destroyed the program within a few years; but worse, it also seriously damaged its own reputation.

The unexpected success is an opportunity, but it makes demands.

It demands to be taken seriously.

It demands to be staffed with the ablest people available, rather than with whoever we can spare.

It demands seriousness and support on the part of management equal to the size of the opportunity.

And the opportunity is considerable.

Incongruities

Typically, these incongruities are macro-phenomena, which occur within a whole industry or a whole service sector.

The major opportunities for innovation exist, however, normally for the small and highly focused new enterprise, new process, or new service.

And usually the innovator who exploits this incongruity can count on being left alone for a long time before the existing businesses or suppliers wake up to the fact that they have new and dangerous competition.

For they are so busy trying to bridge the gap between rising demand and lagging results that they barely even notice somebody is doing something different — something that produces results, that exploits the rising demand

The Bright Idea

Innovations based on a bright idea probably outnumber all other categories taken together.

Seven or eight out of every ten patents belong here, for example.

A very large proportion of the new businesses that are described in the books on entrepreneurs and entrepreneurships are built around “bright ideas”: the zipper, the ballpoint pen, the aerosol spray can, the tab to open soft drink or beer cans, and many more.

And what is called research in many businesses aims at finding and exploiting bright ideas, whether for a new flavor in breakfast cereals or soft drinks, for a better running shoe, or for yet one more nonscorching clothes iron.

Yet bright ideas are the riskiest and least successful source of innovative opportunities.

The casualty rate is enormous.

No more than one out of every hundred patents for an innovation of this kind earns enough to pay back development costs and patent fees.

A far smaller proportion, perhaps as low as one in five hundred, makes any money above its out-of-pocket costs.

And no one knows which ideas for an innovation based on a bright idea have a chance to succeed and which ones are likely to fail.

Why did the aerosol can succeed, for instance?

And why did a dozen or more similar inventions for the uniform delivery of particles fail dismally?

Why does one universal wrench sell and most of the many others disappear?

Why did the zipper find acceptance and practically displace buttons, even though it tends to jam?

(After all, a jammed zipper on a dress, jacket, or pair of trousers can be quite embarrassing.)

Attempts to improve the predictability of innovations based on bright ideas have not been particularly successful.

Equally unsuccessful have been attempts to identify the personal traits, behavior, or habits that make for a successful innovator.

“Successful inventors,” an old adage says, “keep on inventing.

They play the odds.

If they try often enough, they will succeed.”

This belief that you’ll win if only you keep on trying out bright ideas is, however, no more rational than the popular fallacy that to win the jackpot at Las Vegas one only has to keep on pulling the lever.

Alas, the machine is rigged to have the house win 70 percent of the time.

The more often you pull, the more often you lose.

There is actually no empirical evidence at all for the belief that persistence pays off in pursuing the “brilliant idea,” just as there is no evidence of any “system” to beat the slot machines.

Some successful inventors have had only one brilliant idea and then quit: the inventor of the zipper, for instance, or of the ballpoint pen.

And there are hundreds of inventors around who have forty patents to their name, and not one winner.

Innovators do, of course, improve with practice.

But only if they practice the right method, that is, if they base their work on a systematic analysis of the sources of innovative opportunity.

The reasons for both the unpredictability and the high casualty rate are fairly obvious.

Bright ideas are vague and elusive.

I doubt that anyone except the inventor of the zipper ever thought that buttons or hooks-and-eyes were inadequate to fasten clothing, or that anyone but the inventor of the ballpoint pen could have defined what, if anything, was unsatisfactory about that nineteenth—century invention, the fountain pen.

What need was satisfied by the electric toothbrush, one of the market successes of the 1960s?

It still has to be hand-held, after all.

And even if the need can be defined, the solution cannot usually be specified.

That people sitting in their cars in a traffic jam would like some diversion was perhaps not so difficult to figure out.

But why did the small TV set which Sony developed around 1965 to satisfy this need fail in the marketplace, whereas the far more expensive car stereo succeeded?

In retrospect, it is easy to answer this.

But could it possibly have been answered in prospect?

The entrepreneur is therefore well advised to forgo innovations based on bright ideas, however enticing the success stories.

After all, somebody wins a jackpot on the Las Vegas slot machines every week, yet the best any one slot-machine player can do is try not lose more than he or she can afford.

Systematic, purposeful entrepreneurs analyze the systematic areas, the seven sources that I’ve discussed in Chapters 3 through 9.

There is enough in these areas to keep busy any one individual entrepreneur and any one entrepreneurial business or public-service institution.

In fact, there is far more than anyone could possibly fully exploit.

And in these areas we know how to look, what to look for, and what to do.

All one can do for innovators who go in for bright ideas is to tell them what to do should their innovation, against all odds, be successful.

Then the rules for a new venture apply (see Chapter 15).

And this is, of course, the reason why so much of the literature on entrepreneurship deals with starting and running the new venture rather than with innovation itself.

And yet an entrepreneurial economy cannot dismiss cavalierly the innovation based on a bright idea.

The individual innovation of this kind is not predictable, cannot be organized, cannot be systematized, and fails in the overwhelming majority of cases.

Also many, very many, are trivial from the start.

There are always more patent applications for new can openers, for new wig stands, and for new belt buckles than for anything else.

And in any list of new patents there is always at least one foot warmer than can double as a dish towel.

Yet the volume of such bright-idea innovation is so large that the tiny percentage of successes represents a substantial source of new businesses, new jobs, and new performance capacity for the economy.

In the theory and practice of innovation and entrepreneurship, the bright-idea innovation belongs in the appendix.

But it should be appreciated and rewarded.

It represents qualities that society needs: initiative, ambition, and ingenuity.

There is little society can do, perhaps, to promote such innovation.

One cannot promote what one does not understand.

But at least society should not discourage, penalize, or make difficult such innovations.

Seen in this perspective, the recent trend in developed countries, and especially in the United States, to discourage the individual who tries to come up with a bright-idea innovation (by raising patent fees, for instance) and generally to discourage patents as “anticompetitive” is short-sighted and deleterious.

Focusing managerial vision on opportunity

First among these, and the simplest, is focusing managerial vision on opportunity.

People see what is presented to them; what is not presented tends to be overlooked.

And what is presented to most managers are “problems”—especially in the areas where performance falls below expectations—which means that managers tend not to see the opportunities.

They are simply not being presented with them.

Management, even in small companies, usually get a report on operating performance once a month.

The first page of this report always lists the areas in which performance has fallen below budget, in which there is a ‘shortfall,” in which there is a “problem.”

At the monthly management meeting, everyone then goes to work on the so-called problems.

By the time the meeting adjourns for lunch, the whole morning has been taken up with the discussion of those problems.

Of course, problems have to be paid attention to, taken seriously, and tackled.

But if they are the only thing that is being discussed, opportunities will die of neglect.

In businesses that want to create receptivity to entrepreneurship, special care is therefore taken that the opportunities are also attended to (cf. Chapter 3 on the unexpected success).

In these companies, the operating report has two “first pages”: the traditional one lists the problems; the other one lists all the areas in which performance is better than expected, budgeted, or planned for.

For, as was stressed earlier, the unexpected success in one’s own business is an important symptom of innovative opportunity.

If it is not seen as such, the business is altogether unlikely to be entrepreneurial.

In fact the business and its managers, in focusing on the “problems,” are likely to brush aside the unexpected success as an intrusion on their time and attention.

They will say, “Why should we do anything about it?

It’s going well without our messing around with it.”

But this only creates an opening for the competitor who is a little more alert and a little less arrogant.

Typically, in companies that are managed for entrepreneurship, there are therefore two meetings on operating results: one to focus on the problems and one to focus on the opportunities.

One medium-sized supplier of health-care products to physicians and hospitals, a company that has gained leadership in a number of new and promising fields, holds an “operations meeting” the second and the last Monday of each month.

The first meeting is devoted to problems—to all the things which, in the last month, have done less well than expected or are still doing less well than expected six months later.

This meeting does not differ one whit from any other operating meeting.

But the second meeting—the one on the last Monday—discusses the areas where the company is doing better than expected: the sales of a given product that have grown faster than projected, or the orders for a new product that are coming in from markets for which it was not designed.

The top management of the company (which has grown ten-fold in twenty years) believes that its success is primarily the result of building this opportunity focus into its monthly management meetings.

“The opportunities we spot in there,” the chief executive officer has said many times, “are not nearly as important as the entrepreneurial attitude which the habit of looking for opportunities creates throughout the entire management group.”

Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Changing Values and Characteristics

From chapter 19 of Innovation and Entrepreneurship by Peter Drucker

Amazon link: Innovation and Entrepreneurship

In the entrepreneurial strategies discussed so far, the aim is to introduce an innovation.

In the entrepreneurial strategy discussed in this chapter, the strategy itself is the innovation.

The product or service it carries may well have been around a long time—in our first example, the postal service, it was almost two thousand years old.

But the strategy converts this old, established product or service into something new.

It changes its utility, its value, its economic characteristics.

While physically there is no change, economically there is something different and new.

All the strategies to be discussed in this chapter have one thing in common.

They create a customer — and that is the ultimate purpose of a business, indeed, of economic activity.

As was first said more than thirty years ago in my The Practice of Management (New York: Harper & Row, 1954).

But they do so in four different ways:

by creating utility by creating utility

by pricing by pricing

by adaptation to the customer’s social and economic reality by adaptation to the customer’s social and economic reality

by delivering what represents true value to the customer by delivering what represents true value to the customer

... snip, snip ...

These examples are likely to be considered obvious.

Surely, anybody applying a little intelligence would have come up with these and similar strategies?

But the father of systematic economics, David Ricardo, is believed to have said once, “Profits are not made by differential cleverness, but by differential stupidity.”

The strategies work, not because they are clever, but because most suppliers—of goods as well as of services, businesses as well as public-service institutions—do not think.

They work precisely because they are so “obvious.”

Why, then, are they so rare?

For, as these examples show, anyone who asks the question, What does the customer really buy? will win the race.

In fact, it is not even a race since nobody else is running.

What explains this?

One reason is the economists and their concept of “value.”

Every economics book points out that customers do not buy a “product,” but what the product does for them.

And then, every economics book promptly drops consideration of everything except the “price” for the product, a “price” defined as what the customer pays to take possession or ownership of a thing or a service.

What the product does for the customer is never mentioned again.

Unfortunately, suppliers, whether of products or of services, tend to follow the economists.

It is meaningful to say that “product A costs X dollars.”

It is meaningful to say that “we have to get Y dollars for the product to cover our own costs of production and have enough left over to cover the cost of capital, and thereby to show an adequate profit.”

But it makes no sense at all to conclude and therefore the customer has to pay the lump sum of Y dollars in cash for each piece of product A he buys.”

Rather, the argument should go as follows: “What the customer pays for each piece of the product has to work out as Y dollars for us.

But how the customer pays depends on what makes the most sense to him.

It depends on what the product does for the customer.

It depends on what fits his reality.

It depends on what the customer sees as ‘value.’”

Price in itself is not “pricing,” and it is not “value.”

It was this insight that gave King Gillette a virtual monopoly on the shaving market for almost forty years; it also enabled the tiny Haloid Company to become the multibillion-dollar Xerox Company in ten years, and it gave General Electric world leadership in steam turbines.

In every single case, these companies became exceedingly profitable.

But they earned their profitability.

They were paid for giving their customers satisfaction, for giving their customers what the customers wanted to buy, in other words, for giving their customers their money’s worth.

“But this is nothing but elementary marketing,” most readers will protest, and they are right.

It is nothing but elementary marketing.

To start out with the customer’s utility, with what the customer buys, with what the realities of the customer are and what the customer’s values are—this is what marketing is all about.

But why, after forty years of preaching Marketing, teaching Marketing, professing Marketing, so few suppliers are willing to follow, I cannot explain.

The fact remains that so far, anyone who is willing to use marketing as the basis for strategy is likely to acquire leadership in an industry or a market fast and almost without risk.

Entrepreneurial strategies are as important as purposeful innovation and entrepreneurial management.

Together, the three make up innovation and entrepreneurship.

The available strategies are reasonably clear, and there are only a few of them.

But it is far less easy to be specific about entrepreneurial strategies than it is about purposeful innovation and entrepreneurial management.

We know what the areas are in which innovative opportunities are to be found and how they are to be analyzed.

There are correct policies and practices and wrong policies and practices to make an existing business or public-service institution capable of entrepreneurship; right things to do and wrong things to do in a new venture.

But the entrepreneurial strategy that fits a certain innovation is a high-risk decision.

Some entrepreneurial strategies are better fits in a given situation, for example, the strategy that I called entrepreneurial judo, which is the strategy of choice where the leading businesses in an industry persist year in and year out in the same habits of arrogance and false superiority.

We can describe the typical advantages and the typical limitations of certain entrepreneurial strategies.

Above all, we know that an entrepreneurial strategy has more chance of success the more it starts out with the users—their utilities, their values, their realities.

An innovation is a change in market or society.

It produces a greater yield for the user, greater wealth-producing capacity for society, higher value or greater satisfaction.

The test of an innovation is always what it does for the user.

Hence, entrepreneurship always needs to be market-focused, indeed, market-driven.

Still, entrepreneurial strategy remains the decision-making area of entrepreneurship and therefore the risk-taking one.

It is by no means hunch or gamble.

But it also is not precisely science.

Rather, it is judgment.

The Shakeout (calendarize this?)

The “shakeout” sets in as soon as the “window” closes.

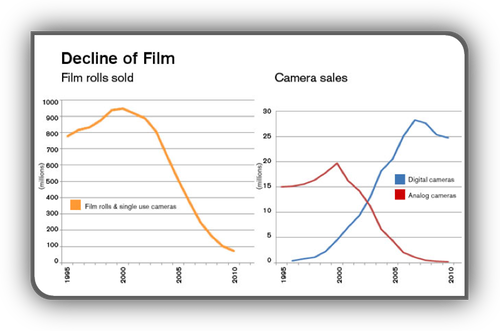

And the majority of ventures started during the “window” period do not survive the shakeout, as has already been shown for such high-tech industries of yesterday as railroads, electrical apparatus makers, and automobiles.

As these lines are being written, the shakeout has begun among microprocessor, minicomputer, and personal computer companies—only five or six years after the “window” opened.

Today, there are perhaps a hundred companies in the industry in the United States alone.

Ten years hence, by 1995, there are unlikely to be more than a dozen left of any size or significance.

But which ones will survive, which ones will die, and which ones will become permanently crippled—able neither to live nor to die—is unpredictable.

In fact, it is futile to speculate.

Sheer size may ensure survival.

But it does not guarantee success in the shakeout, otherwise Allied Chemical rather than DuPont would today be the world’s biggest and most successful chemical company.

In 1920, when the “window” opened for the chemical industry in the United States, Allied Chemical looked invincible, if only because it had obtained the German chemical patents which the U.S. government had confiscated during World War I.

Seven years later, after the shakeout, Allied Chemical had become a weak also-ran.

It has never been able to regain momentum.

No one in 1949 could have predicted that IBM would emerge as the computer giant, let alone that such big, experienced leaders as G.E. or Siemens would fail completely.

No one in 1910 or 1914 when automobile stocks were the favorites of the New York Stock Exchange could have predicted that General Motors and Ford would survive and prosper and that such universal favorites as Packard or Hupmobile would disappear.

No one in the 1870s and 1880s, the period in which the modern banks were born, could have predicted that Deutsche Bank would swallow up dozens of the old commercial banks of Germany and emerge as the leading bank of the country.

That a certain industry will become important is fairly easy to predict.

There is no case on record where an industry that reached the explosive phase, the “window” phase, as I called it, has then failed to become a major industry.

The question is, Which of the specific units in this industry will be its leaders and so survive?

This rhythm—a period of great excitement during which there is also great speculative ferment, followed by a severe “shakeout”—is particularly pronounced in the high-tech industries.

In the first place, such industries are in the limelight and thus attract far more entrants and far more capital than more mundane areas.

Comments by Warren Buffett.

Also the expectations are much greater.

More people have probably become rich building such prosaic businesses as a shoe-polish or a watchmaking company than have become rich through high-tech businesses.

Yet no one expects shoe-polish makers to build a “billion-dollar business,” nor considers them a failure if all they build is a sound but modest family company.

(Managing the Family Business: see December 28 and 29 in The Daily Drucker)

High tech, by contrast, is a “high-low game,” in which a middle hand is considered worthless.

And this makes high-tech innovation inherently risky.

But also, high tech is not profitable for a very long time.

The world’s computer industry began in 1947-48.

Not until the early 1980s, more than thirty years later, did the industry as a whole reach break-even point.

To be sure, a few companies (practically all of them American, by the way) began to make money much earlier.

And one, IBM, the leader, began to make a great deal of money earlier still.

But across the industry the profits of those few successful computer makers were more than offset by the horrendous losses of the rest; the enormous losses, for instance, which the big international electrical companies took in their abortive attempts to become computer manufacturers.

And exactly the same thing happened in every earlier “high-tech” boom—in the railroad booms of the early nineteenth century, in the electrical apparatus and the automobile booms between 1880 and 1914, in the electric appliance and the radio booms of the 1920s, and so on.

One major reason for this is the need to plow more and more money back into research, technical development, and technical services to stay in the race.

High tech does indeed have to run faster and faster in order to stand still.

This is, of course, part of its fascination.

But it also means that when the shakeout comes, very few businesses in the industry have the financial resources to outlast even a short storm.

This is the reason why high-tech ventures need financial foresight even more than other new ventures, but also the reason why financial foresight is even scarcer among high-tech new ventures than it is among new ventures in general.

(Find “financial foresight” in Innovation and Entrepreneurship and see chapter 3 in The Changing World of the Executive)

There is only one prescription for survival during the shakeout: entrepreneurial management (described in Chapters 12-15).

What distinguished Deutsche Bank from the other “hot” financial institutions of its time was that Georg Siemens thought through and built the world’s first top management team.

What distinguished DuPont from Allied Chemical was that DuPont in the early twenties created the world’s first systematic organization structure, the world’s first long-range planning, and the world’s first system of management information and control.

Allied Chemical, by contrast, was run arbitrarily by one brilliant egomaniac.

But this is not the whole story.

Most of the large companies that failed to survive the more recent computer shakeout — G.E. and Siemens, for instance—are usually considered to have first-rate management.

And the Ford Motor Company survived, though only by the skin of its teeth, even though it was grotesquely mismanaged during the shakeout years.

Entrepreneurial management is thus probably a precondition of survival, but not a guarantee thereof.

And at the time of the shakeout, only insiders (and perhaps not even they) can really know whether a knowledge-based innovator that has grown rapidly for a few boom years is well managed, as DuPont was, or basically unmanaged, as Allied Chemical was.

By the time we do know, it is likely to be too late.

Innovation and Entrepreneurship

A revolution in every generation — not the answer

“Every generation needs a new revolution,” was Thomas Jefferson’s conclusion toward the end of his long life.

His contemporary, Goethe, the great German poet, though an arch-conservative, voiced the same sentiment when he sang in his old age:

Reason becomes nonsense, /Boons afflictions.

Both Jefferson and Goethe were expressing their generation’s disenchantment with the legacy of Enlightenment and French Revolution.