|

Peter Drucker ::: political / social ecologist

The Über Mentor

Remembering Peter Drucker

(from the November 2009 issue of The Economist)

“To know something,

to really understand something important,

one must look at it from sixteen different angles.

People are perceptually slow,

and there is no shortcut to understanding;

it takes a great deal of time.”

discontinuity ::: the black cylinder experiment and its relevance ::: beyond the numbers

… but the only thing that is “new” about political ecology is the name.

As a subject matter and human concern, it can boast ancient lineage, going back all the way to Herodotus and Thucydides.

It counts among its practitioners such eminent names as de Tocqueville and Walter Bagehot.

Its charter is Aristotle’s famous definition of man as “zoon politikon,” that is, social and political animal.

As Aristotle knew (though many who quote him do not), this implies that society, polity, and economy though man’s creations, are nature to man, who cannot be understood apart from and out of them.

It also implies that society, polity and economy are a genuine environment, a genuine whole, a true “system,” to use the fashionable term, in which everything relates to everything else and in which men, ideas, institutions, and actions must always be seen together in order to be seen at all, let alone to be understood.

Political ecologists are uncomfortable people to have around.

Their very trade makes them defy conventional classifications, whether of politics, of the market place, or of academia.

“Political ecologists” emphasize that every achievement exacts a price and, to the scandal of good “liberals",” talk of “risks” or “trade-offs,” rather than of “progress.”

But they also know that the man-made environment of society, polity, and economics, like the environment of nature itself, knows no balance except dynamic disequilibrium.

Political ecologists therefore emphasize that the way to conserve is purposeful innovation—and that hardly appeals to the “conservative.”

Political ecologists believe that the traditional disciplines define fairly narrow and limited tools rather than meaningful and self-contained areas of knowledge, action, and events—in the same way in which the ecologists of the natural environment know that swamp or the desert is the reality and ornithology, botany, and geology only special-purpose tools.

Political ecologists therefore rarely stay put.

It would be difficult to say, I submit, which of chapters in this volume are “management,” which “government” or “political theory,” which “history” or “economics.”

The task determines the tools to be used: but this has never been the approach of academia.

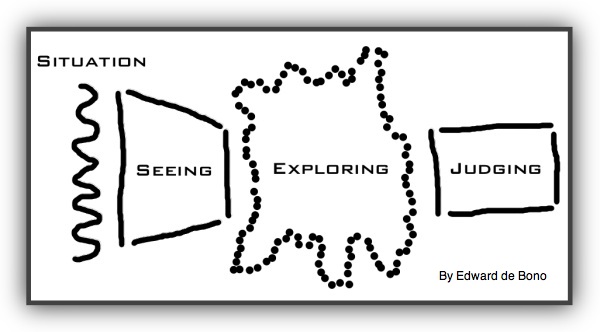

From analysis to perception — the new world view

Form and Function Connections: see chapters

On Being the Right Size and On Being the Wrong Size

in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices and others.

Students of man’s various social dimensions—government, society, economy, institutions—traditionally assume their subject matter to be accessible to full rational understanding.

Indeed, they aim at finding “laws” capable of scientific proof.

Human action, however, they tend to treat as nonrational, that is, as determined by outside forces, such as their “laws.”

The political ecologist, by contrast, assumes that his subject matter is far too complex ever to be fully understood—just as his counterpart, the natural ecologist, assumes this in respect to the natural environment.

But precisely for this reason the political ecologist will demand—like his counterpart in the natural sciences—responsible actions from man and accountability of the individual for the consequences, intended or otherwise, of his actions.

They aim at an understanding of the specific natural environment of man, his “political ecology,” as a prerequisite to effective and responsible action, as an executive, as a policy-maker, as a teacher, and as a citizen.

Not one reader, I am reasonably sure, will agree with every essay; indeed, I expect some readers to disagree with all of them.

by bobembry: Carefully reading his writings is a time-investment — an opportunity to travel a brainroad and create a mental landscape (brainscape).

Having the ability to revisit one of these provides a brainaddress — a way back to a brainscape.

In this case the brainroad is the mental terrain you covered during your reading.

The brainscape is the entire topic landscape.

Creating a brainaddress will take a little thinking.

Your collection of bookmarks is a set of brainaddresses.

Which ones are truly valuable?

Which ones will mean something ten years from now?

But then I long ago learned that the most serious mistakes are not being made as a result of wrong answers.

The truly dangerous thing is asking the wrong questions.

Men, Ideas & Politics

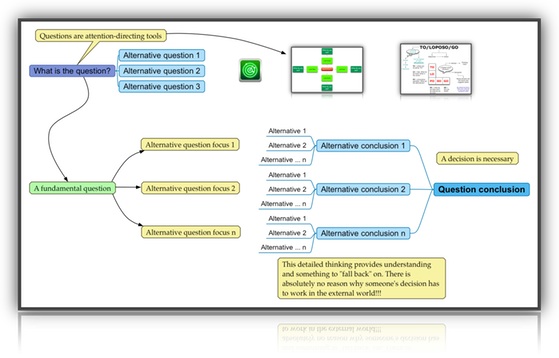

Questions are attention-directing tools

Larger

Druckerisms

366 Days of Insight and Motivation for Getting the Right Things Done

by Peter Drucker with Joseph Maciariello

Amazon link: The Daily Drucker: 366 Days of Insight and Motivation for Getting the Right Things Done

26 JAN — A Social Ecologist

For me the tension between the need for continuity and the need for innovation and change was central to society and civilization.

I consider myself a “social ecologist,” concerned with man’s man-made environment the way the natural ecologist studies the biological environment.

The term “social ecology” is my own coinage.

But the discipline itself boasts an old and distinguished lineage.

Its greatest document is Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America.

But no one is as close to me in temperament, concepts, and approach as the mid-Victorian Englishman Walter Bagehot.

Living (as I have) in an age of great social change, Bagehot first saw the emergence of new institutions: civil service and cabinet government, as cores of a functioning democracy, and banking as the center of a functioning economy.

A hundred years after Bagehot, I was first to identify management as the new social institution of the emerging society of organizations and, a little later, to spot the emergence of knowledge as the new central resource, and knowledge workers as the new ruling class of a society that is not only “post-industrial” but post-socialist and, increasingly, post-capitalist.

As it had been for Bagehot, for me too the tension between the need for continuity and the need for innovation and change was central to society and civilization.

Thus, I know what Bagehot meant when he said that he saw himself sometimes as a liberal Conservative and sometimes as a conservative Liberal but never as a “conservative Conservative” or a “liberal Liberal.”

1 DEC — The Work of the Social Ecologist

If this change is relevant and meaningful, what opportunities does it offer?

Now as to what the work of the social ecologist is: First of all, it means looking at society and community by asking these questions:

“What changes have already happened that do not fit ‘what everybody knows’?”

“What are the ‘paradigm changes’?”

“Is there any evidence that this is a change and not a fad?”

And, finally, one then asks: “If this change is relevant and meaningful, what opportunities does it offer?”

A simple example is the emergence of knowledge as a key resource.

The event that alerted me to the fact that something was happening was the passage of the GI Bill of Rights in the United States after the Second World War.

This law gave every returning war veteran the right to attend college, with the government paying the bill.

It was a totally unprecedented development.

These considerations led me to the question: “What impact does this have on expectations, on values, on social structure, on employment, and so on?”

And once this question was asked—I first asked it in the late 1940s—it became clear that knowledge as a productive resource had attained a position in society as never before in human history.

We were clearly on the threshold of a major change.

Ten years later, by the mid-1950s, one could confidently talk of a “knowledge society,” of “knowledge work” as the new center of the economy, and of the “knowledge worker” as the new, ascendant workforce.

Ecology is mentioned in “From Analysis to Perception — The New World View” found in The New Realities or The Essential Drucker

Peter Drucker's “My life as a knowledge worker”

Knowledge: Its economic and productivity

The Ecological Vision: Reflections on the American Condition

What’s it like to talk to Drucker?

He draws on a rich well of knowledge and peppers his conversation with analogy, says Bachmann.

“He is in no way bound by the language and disciplines of business.

When he talks about an issue, he very well could be talking about César Franck or Franz Liszt using musical examples, then he skips to Japanese art, and then Egyptian art, and draws that together with some example of the Catholic Church and the formation of education — Mentor

Drucker looks for simplicity but likes to convey complexity.

He loves simplicity but realizes that getting there means making connections: to the past, to related fields.

He answers questions by trotting through history, art, science.

Listening to him, you learn not just the answer but also how to make connections between disparate subjects and thus deepen your understanding.

It makes you, the listener, more valuable as an adviser and teacher — Peter’s Principles by Harriet Rubin

What Everybody Knows Is Frequently Wrong What Everybody Knows Is Frequently Wrong

Approach Problems with Your Ignorance—Not Your Experience Approach Problems with Your Ignorance—Not Your Experience

Keywords: tlnkwecology

|

![]()

![]()