Which paragraphs below represent concept patterns?

The idea for these lectures was conceived about a year and a half ago when I got a telephone call and somebody said, “You don’t know me, but I understand that you have done a lot of work in research management.”

And I said, “Yes, I’ve probably made more mistakes in research management than most other people, so I’m qualified as an expert.”

And that person said, “Three months ago I moved from being a biochemist into being the director of one of the world’s largest labs.

And for three months I have been studying what my job is.

And I’ve come to the point where I would like to ask you a question:

Do you think research can be managed?”

And I was near the point of saying, “If you feel you have to ask this question, why don’t you go back and be a biochemist again?”

And then I thought for a while and said, “The answer is yes—but.

It can be managed, but it cannot be managed the way most other things are being managed.

It requires very different things.”

And out of this I started to say it’s about time I try to put together what I have learned in many years of seeing good people struggle with this issue.

And most of the things I developed to help this particular research director—who, by the way, is still in the job and by now I think enjoys it quite a bit—I applied to knowledge of any kind.

In most of human work, change is very slow.

Continuity, both of work and tools, is the rule.

When it comes to skills, it is still largely proved that if you get going through that apprenticeship at age 19, you have a very good chance of not having to learn anything new until you retire.

But knowledge work is the exception.

Change comes very rapidly.

If Socrates the stonemason—that’s how he made his living—came and worked for one of those mason yards that make crosses for our cemeteries, believe me, he would not have to learn much.

Most of the tools are pretty much the same, except that some of them now have a battery.

But if Socrates the philosopher came into one of our philosophy departments today, he would not understand one single word.

And I’m not saying that they’re better than he was.

But they’re totally different.

And that is typical.

I just finished a few weeks ago reading a history of the library.

And the concepts of the library change every 30 or 40 years.

One of the great weaknesses of library school is that it teaches the current technology as the permanent one, when all experience shows that what librarians have to learn is how to learn.

Or take registered nurses.

Over the last 20 or 30 years at least one thing has remained the same: the purpose.

But the way the job is done is almost beyond all recognition for a nurse who started in 1950.

Knowledge, by definition, changes very fast.

And skills, by definition, change very slowly.

This is one of the first things to say in managing.

And let me say this was probably my greatest contribution to the research director.

After we had worked on it for some time, it hit me that his very big, very famous lab was being basically run statically.

We add discoveries, and we add insights, but we don’t change the way we work.

And once we understood it, we began to realize that to overcome his bottlenecks, his frustrations—not all of them, but some of them—he had to build in continuous feedback and learning.

Mostly, this meant sitting down with people and saying, “What have we learned that will force us, or will enable us, will help us, to do things differently?”

As some of you who are in academia know, we don’t do this well.

We basically assume the old craftsman’s assumption about apprenticeship that, once you have gotten your Ph.D., you stop learning and start teaching.

Instead, we should be saying, “That’s when you start helping others to learn.

sidebar ↓

Learning to perform in society and

not just learning to answer

true or false, multiple-choice and essay questions.

main brainroad continues ↓

And that’s when you start learning yourself.”

A knowledge-based organization has to be an entrepreneurial organization in the sense that it always starts out to make itself obsolete, because that is the characteristic of knowledge.

It is not the characteristic of a skill.

And I’m not saying that I know how to do it, and I’m not saying that we know how to do it.

I’m saying that we’re beginning to realize that this makes a tremendous difference.

You’ve probably heard the story of the old grad who comes back to the fortieth reunion, and the old economics prof is still there.

It is May—that’s when reunions are held—so this is final exam time.

And the grad looks at the final exam and says, “Professor Smithers, these are the same questions you asked us 40 years ago.”

And Smithers nods and says, “Yes, but the answers are different.”

We always thought it was a joke. No!

This is wisdom.

The answers to questions do not remain the same.

The answers are different, because we have learned a lot.

What we mostly learn is that the answers that gave you an “A+” 40 years ago are the wrong answers.

The way we go about solving problems has changed, because that’s what you learn.

You learn to do a little better, to push back that infinite boundary of ignorance just a bit.

Among the implications of this is that you have to build in organized abandonment.

Otherwise, you collapse under the overload.

One of the things you learn from working with research organizations is that they become constipated because there’s too much.

Nobody has unlimited resources.

In knowledge work, you have to start out with the need to change, to grow, to do the new, to run very fast with something that opens up.

And you can only do that if you make resources available by freeing them from where there are no longer results …

sidebar ↓

… results are different from outcomes because they ↑ have to make a contribution on the outside → to society and the individual …

main brainroad continues ↓

Another thing we need is specialization.

Most human beings excel at one thing at most, and not very many excel even at one.

And very few people excel at more than one.

And I don’t think you’ll find anybody who excels at three.

Yet, at the same time, the computer programmer produces nothing by himself.

Results are interdisciplinary.

So, yes, you have to be a specialist.

But knowledge has another very peculiar characteristic, which is that the important new advances do not come out of the specialist’s discipline.

They come from the outside.

It makes no difference what you look at.

Every one of the things that have transformed the discipline of history, for instance, came from outside—from psychoanalysis and psychology, from economics, from population statistics, from archaeology.

These are all things that no historian, during the time I went to school, ever heard of.

And if he did, he was told by his prof, “Look, you study to learn how to read a document in the archives.

That’s difficult enough.”

The same is true when you look at the forebears of the computer.

Very little of it is computer ancestry.

Most of it came from other disciplines.

Or look at the Mazda Miata, which has its American design center someplace in Orange County.

Where did those impulses, those ideas, come from?

Not one came out of automotive design.

They came from metallurgy, they came from material science, because that car is made with composite materials and plastics and what have you—from all kinds of things that I’m reasonably sure no automotive engineer ever learned in class.

So how do you organize for this—the fact that you must have a discipline as a basis, but you also have to organize an awareness of the meaning of things that happen on the outside?

Fortune favors the prepared mind ↓

The application of knowledge to knowledge: the importance of

accessing, interpreting, connecting, and translating knowledge” … more …

A discipline is a necessary container, but it’s temporary — very temporary.

Young people not knowing

how to connect their knowledge

— Drucker on Asia

The individual IN ENTREPRENEURIAL SOCIETY

And so how do you do it?

A good many companies have learned that it isn’t enough to have a research director who is a whiz in a certain specialty.

You need a technologist who has an awareness of what goes on in other areas.

And this is not something we yet know how to do systematically, but it’s something we will have to learn.

The last thing to say is that this is work and not good intentions.

It’s got to be measured.

And yet whenever I use that word, people get upset, and they say, “What we do can’t be measured.”

I don’t think I’ve told you the story of how I got into the management of research.

We had just moved from New England to New York, and I was teaching management at NYU.

And I had a neighbor who was research director of one of the large pharmaceutical companies, and we discovered that he and I were both enthusiastic but equally incompetent chess players.

Nobody wanted to play with us, and so we played together.

And one day I came home, and there was this fellow in a great state of agitation.

He had waited for me.

And I said, “What’s the matter, Stanley?”

He was always very quiet.

And he said, “You know, I’ve always been complaining to you how totally disorganized our company is, and how we need management.

And then I told you about the new president of ours who came in six weeks ago, and how delighted I was with him because he was going to actually start managing the place.

Well, he called me in today and said, ‘Stanley, I’ve accepted your proposal, and I’ll appoint a budget committee, and everybody will have a budget.’

And I said, ‘Wonderful!’

And he said, ‘Stanley, you’re going to be chairman of this committee.’

And I said, ‘Wonderful!’

And he said, ‘The first budget I want, Stanley, is that of the research department.’

And I said, ‘Mr. President, what we do in research isn’t determined by us, but by what a lot of rats and guinea pigs and white mice and hamsters do when we put substances under their skin or push them down their gullet.’

And he said, ‘If that is the case, Stanley, please write out your resignation and nominate the brightest hamster.

We’ll make him research director.”

It took me six weeks to get across to Stanley what the president had been trying to tell him.

And he never quite accepted it.

A good many people still feel that way when you say “knowledge work.”

In other words, knowledge is not, in that sense, quantitative.

And so we will have to learn to think through how we measure and how we appraise.

And then I think we can begin to focus knowledge work on results.

One result is productivity, which is woefully low—not because people don’t work hard, but because we don’t know what productivity means.

We made the same mistake with manual work—measuring productivity by how much sweat there is, how hard it is, how many hours are being worked, and how unpleasant it is.

Before [Frederick] Taylor, the main measurement of productivity was how tired people were when they got home.

Well, that’s not the measurement of productivity; that’s the measurement of incompetence.

And we are doing that with knowledge work.

Let me come back to the question I started out with—the question posed by my friend, the research manager, over the telephone a year and a half ago:

“Can knowledge be managed?”

The answer is: We don’t know.

But we do know that it has to be managed, and if knowledge is not managed it only costs and doesn’t produce.

And we know that it has to be managed differently, that you must start out with a few uncommon assumptions, counterintuitive because that’s not the way we look at other work.

You must start out with the assumption that knowledge changes itself—that [the] more you know, the more it changes.

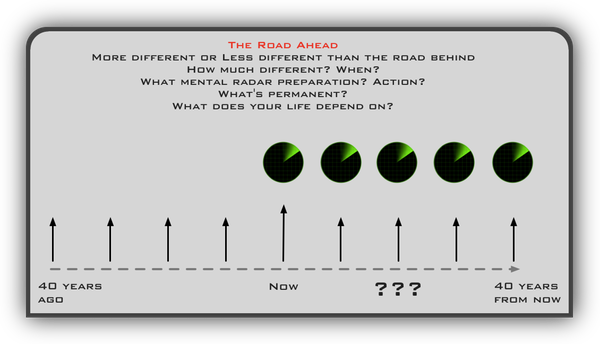

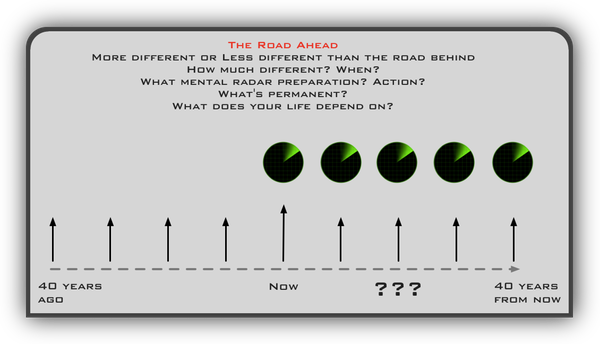

The road ahead … ↑ going where no one has gone before ↑ ↓

There’s the assumption that, by itself, knowledge is an input, and it has to be integrated to become an output.

And there’s the assumption that knowledge must be concentrated.

If you splinter it, you get very little.

You get journalism, but not knowledge.

And, finally, we know that there is only one standard for knowledge.

Maybe excellence is a big word.

I hate to use it.

But there has to be that kind of self-respect that will not allow you to do shoddy work.

And those are some of the things we know about knowledge as a resource.

It’s always been around, but it’s been a very rare resource.

And for most human pursuits you didn’t need it at all, or very little.

But now it’s the key resource of a modern developed economy and society, and we are just beginning to learn to manage it.

The future that has already happened

Dealing with risk and uncertainty

From a lecture delivered at Claremont Graduate School (currently known as Claremont Graduate University).

Knowledge and technology

Long years of profound changes

How could you calendarize this ↑?

![]()