|

Following is from Post-Capitalist Society by Peter Drucker

Amazon link: Post-Capitalist Society

“EVERY FEW HUNDRED YEARS in Western history there occurs a sharp transformation.

We cross what in an earlier book (The New Realities—1989) I called a “divide.”

Within a few short decades, society rearranges itself—its worldview; its basic values; its social and political structure; its arts; its key institutions.

(Can you identify what these components might be?)

(calendarize this?)

Fifty years later, there is a new world.

And the people born then cannot even imagine the world in which their grandparents lived and into which their own parents were born.

We are currently living through just such a transformation.”

The Limping Middle Class

“It is creating the post-capitalist society, which is the subject of this book.”

“That knowledge has become the resource,

rather than a resource,

is what makes our society “post-capitalist.”

This fact changes—fundamentally—the structure of society.

It creates new social and economic dynamics.

It creates new politics.

The post-capitalist society

is both a knowledge society and a society of organizations,

each dependent on the other and yet

each very different in its concepts, views, and values.

It is the very nature of knowledge

that it changes fast

and that today’s certainties

will be tomorrow’s absurdities.” — PFD

Chapter 3 — Labor, Capital, and Their Future

If knowledge is the resource of post-capitalist society, what then will be the future role and function of the two key resources of capitalist (and socialist) society, labor and capital?

Socially, the new challenges will predominate.

(to be discussed in Chapters 4 “The Productivity of the New Workforces” and 5 “The Responsibility Based Organization” and in the last part of this book — Knowledge: Its Economics and Its Productivity; The Accountable School; The Educated Person)

And the success of post-capitalist society will largely depend on our answers to them.

But politically, the unfinished business of capitalist society will be highly visible: the disappearance of labor as a factor of production, and the redefinition of the role and function of traditional capital.

We have moved already into an “employee society” where labor is no longer an asset.

We equally have moved into a “capitalism” without capitalists—which defies everything still considered self-evident truth, if not “the laws of nature,” by politicians, lawyers, economists, journalists, labor leaders, business leaders; in short, by most everybody regardless of political persuasion.

For that reason, these issues will be in the political spotlight in the decades ahead.

To be able to tackle successfully the new challenges of this transition period, we must resolve these two items of unfinished business: the future role and function of labor, and the future role and function of money capital.

See articles in the news for examples.

“THE NEW CHALLENGE facing the post-capitalist society is the productivity of knowledge workers and service workers.” (calendarize this?)

“To improve the productivity of knowledge workers will in fact require drastic changes in the structure of the organizations of post-capitalist society, and in the structure of society itself” (managing oneself).

“Even more drastic, indeed revolutionary, are the requirements for obtaining productivity from service workers”

Economic stagnation and severe social tension from

failure to raise knowledge and service worker productivity

Chapter 19 in Management, Revised Edition

Chapter 5 in Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Knowledge: Its Economics and Productivity

For clues to navigating toward tomorrowS … (calendarize these?)

Management’s New Paradigm Management’s New Paradigm

Management Challenges for the 21st Century Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Managing In The Next Society Managing In The Next Society

The Next Society from the Economist

From Analysis to Perception — The New Worldview From Analysis to Perception — The New Worldview

The question of the right size for a given task or a given organization will become a central challenge.

In an information-based society, bigness becomes a “function” and a dependent, rather than an independent, variable.

Increasingly, therefore, the question of the right size for a task will become a central one.

All of them are needed, but each for a different task and in a different ecology.

The right size will increasingly be whatever handles most effectively the information needed for task and function.

See Strategies and Structures in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

The productivity of knowledge is going to be the determining factor in the competitive position of a company, an industry, an entire country.

No country, industry, or company has any “natural” advantage or disadvantage.

The only advantage it can possess is the ability to exploit universally available knowledge.

The only thing that increasingly will matter in national as in international economics is management's performance in making knowledge productive. — Knowledge: its economics and productivity

Knowledge workers will increasingly determine the shape of the successful employing organizations. — Management, Revised Edition !!!

In the knowledge society, it is not the individual who performs.

The individual is a cost center rather than a performance center.

It is the organization that performs. (Across multiple time dimensions: explore the life stories of HP, Kodak, RIM or RCA) — A Century of Social Transformation by Peter Drucker

Executive Jobs and Growth

You have to learn to manage in situations where you don’t have command authority, where you are neither controlled nor controlling.

That is the fundamental change.

Management textbooks still talk mainly about managing subordinates.

But you no longer evaluate an executive in terms of how many people report to him or her.

That standard doesn’t mean as much as the complexity of the job, the information it uses and generates, and the different kinds of relationships needed to do the work.

Similarly, business news still refers to managing subsidiaries.

But this is the control approach of the 1950s or 1960s.

The reality is that the multinational corporation is rapidly becoming an endangered species.

Businesses used to grow in one of two ways: from grass-roots up or by acquisition.

In both cases, the manager had control.

Today businesses grow through alliances, all kinds of dangerous liaisons and joint ventures, which, by the way, very few people understand.

This new type of growth upsets the traditional manager, who believes he or she must own or control sources and markets.

Moving Beyond Capitalism?

… Of late, some of capitalism’s biggest boosters, people such as yourself and the financier George Soros, have become its biggest critics. What is your critique?

Drucker: The Man Who Invented the Corporate Society

I am for the free market.

Even though it doesn’t work too well, nothing else works at all.

But I have serious reservations about capitalism as a system because it idolizes economics as the be-all and end-all of life.

It is one-dimensional.

For example, I have often advised managers that a 20-1 salary ratio is the limit beyond which they cannot go if they don’t want resentment and falling morale to hit their companies.

I worried back in the 1930s (The End of Economic Man) that the great inequality generated by the Industrial Revolution would result in so much despair that something like fascism would take hold.

Unfortunately, I was right.

Today, I believe it is socially and morally unforgivable when managers reap huge profits for themselves but fire workers.

As societies, we will pay a heavy price for the contempt this generates among the middle managers and workers.

In short, whole dimensions of what it means to be a human being and treated as one are not incorporated into the economic calculus of capitalism.

For such a myopic system to dominate other aspects of life is not good for any society.

With regard to the market, there are several serious problems with the theory itself.

First of all, the theory assumes there is one homogeneous market.

In reality, there are three overlapping markets that, by and large, don’t interchange: an international market in money and information, national markets, and local markets.

Most of what passes for transnational economic money, of course, is only virtual money.

The London interbank market each day has a greater volume of activity in dollar terms than the whole world would need for a year to finance all economic transactions.

This is functionless money.

It cannot possibly earn any return since it serves no function.

It has no purchasing power.

It is, therefore, totally speculative and prone to panics as it rushes here and there to earn that last 64th of 1 percent.

Then, there is a large national economy which is not exposed to international commerce.

Some 24 percent of U.S. economic activity is exposed to trade.

In Japan, it is only 8 percent.

Then there is the local economy.

The hospital near my home has very high-quality care and is very competitive.

But it does not compete with any hospital forty miles away in Los Angeles.

The effective market area for hospitals in the U.S. is about ten miles because, for some obscure reason no economist would be able to figure out, people like to be close to their sick mothers.

Also, what drives markets has changed.

The economic center of gravity shifted sometime during this century.

In the nineteenth century, with steel and steam, supply generated demand.

Since the Great Depression, however, the tables have turned: In traditional products, from home construction to cars, demand must come before supply although this is not yet true today of information and electronics, which stimulate demand.

Beyond this definition of markets, the truly profound issue is that market theory is based on an assumption of equilibrium and thus cannot accommodate change, let alone innovation.

Rather, the real pattern of economic activity, as Joseph Schumpeter recognized as long ago as 1911, is “a moving disequilibrium” caused by the process of creative destruction as new markets with new products and new demand are made at the expense of old ones.

Market outcomes cannot, therefore, be explained in terms of what the theory would have predicted.

The market is in fact not a predictable system, but inherently unstable.

And if it is not predictable, you cannot base your behavior on it.

That is a pretty serious limitation for a theory of human behavior.

All we can say is that, in the end, any long-term equilibrium is the result of a lot of short-term adaptations to market signals.

This, finally, is the strength of the market: It is a disciplinarian for the short term.

By providing feedback through prices, it discourages you from squandering time and resources going off in all directions like King Arthur’s knights.

The old idea was that if you rode on long enough you would run into something.

The market tells you that if you don’t run into something in five weeks, you better change course or do something else.

Beyond the short term, the market is useless.

You know, I have sat in on more than my share of research planning for large companies.

Fundamentally, this activity is an act of faith.

When the chief financial officer asks, as he always does, “What will be the return?” on this or that project, the only answer is “We will know in ten years.”

Years ago you wrote about pension fund ownership of the American economy, calling it “capitalism sans capitalists” where workers’ retirement funds own the means of production.

Today, this dispersion of wealth has gone even further through the explosion of mutual funds—more than 51 percent of Americans own shares of stock.

Have we arrived at mass capitalism or post-capitalism?

Well, to call it post-capitalism is merely to say we don’t know what to call it.

You also can’t call it economic democracy since there is no organized form of governance associated with this mass ownership.

What is certain is that it is a totally new phenomenon in history. …

Managing in the Next Society

Peter Drucker

If Socialism is defined, as Marx defined it, as ownership of the means of production by the employees, then the United States has become the most “socialist” country around — while still remaining the most “capitalist” one as well. continue

That knowledge has become THE resource, rather than a resource, is what makes our society “post-capitalist.” — Post Capitalist Society and Post Capitalist Polity

This fact changes—fundamentally—the structure of society.

It creates new social and economic dynamics.

It creates new politics.”

The Society of Organizations and the accompanying destabilization

The new workforce

The Manufacturing Paradox

In the closing years of the twentieth century, the world price of the steel industry’s biggest single product—hot-rolled coil, the steel for car bodies—plunged from $460 to $260 a ton.

Yet these were boom years in America and prosperous times in most of continental Europe, with automobile production setting records.

The steel industry’s experience is typical of manufacturing as a whole.

Between 1960 and 1999, both manufacturing’s share in America’s GDP and its share of total employment roughly halved, to around 15 percent.

Yet in the same forty years manufacturing’s physical output doubled or tripled.

In 1960, manufacturing was the center of the American economy, and of the economies of all other developed countries.

By 2000, as a contributor to GDP it was easily outranked by the financial sector.

The relative purchasing power of manufactured goods (what economists call the terms of trade) has fallen by three-quarters in the past forty years.

Whereas manufacturing prices, adjusted for inflation, are down by 40 percent, the prices of the two main knowledge products, health care and education, have risen about three times as fast as inflation.

In 2000, therefore, it took five times as many units of manufactured goods to buy the main knowledge products as it had done forty years earlier.

The purchasing power of workers in manufacturing has also gone down, although by much less than that of their products.

Their productivity has risen so sharply that most of their real income has been preserved.

Forty years ago, labor costs in manufacturing typically accounted for around 30 percent of total manufacturing costs; now they are generally down to 12-15 percent.

Even in cars, still the most labor-intensive of the engineering industries, labor costs in the most advanced plants are no higher than 20 percent.

Manufacturing workers, especially in America, have ceased to be the backbone of the consumer market.

At the height of the crisis in America’s “rust belt,” when employment in the big manufacturing centers was ruthlessly slashed, national sales of consumer goods barely budged.

What has changed manufacturing, and sharply pushed up productivity, are new concepts.

Information and automation are less important than new theories of manufacturing, which are an advance comparable to the arrival of mass production eighty years ago.

Indeed, some of these theories, such as Toyota’s “lean manufacturing,” do away with robots, computers, and automation.

One highly publicized example involves replacing one of Toyota’s automated and computerized paint-drying lines by half a dozen hair-dryers bought in a supermarket.

Manufacturing is following exactly the same path that farming trod earlier.

Beginning in 1920, and accelerating after the Second World War, farm production shot up in all developed countries.

Before the First World War, many Western European countries had to import farm products.

Now there is only one net farm importer left: Japan.

Every single European country now has large and increasingly unsalable farm surpluses.

In quantitative terms, farm production in most developed countries today is probably at least four times what it was in 1920 and three times what it was in 1950 (except in Japan).

But whereas at the beginning of the twentieth century farmers made up the largest single group in the working population in most developed countries, now they account for no more than 3 percent in any developed country.

And whereas at the beginning of the twentieth century agriculture was the largest single contributor to national income in most developed countries, in 2000 in America it contributed less than 2 percent to GDP.

Manufacturing is unlikely to expand its output in volume terms as much as agriculture did, or to shrink as much as a producer of wealth and of jobs.

But the most believable forecast for 2020 suggests that manufacturing output in the developed countries will at least double, while manufacturing employment will shrink to 10-12 percent of the total workforce.

Managing in the Next Society

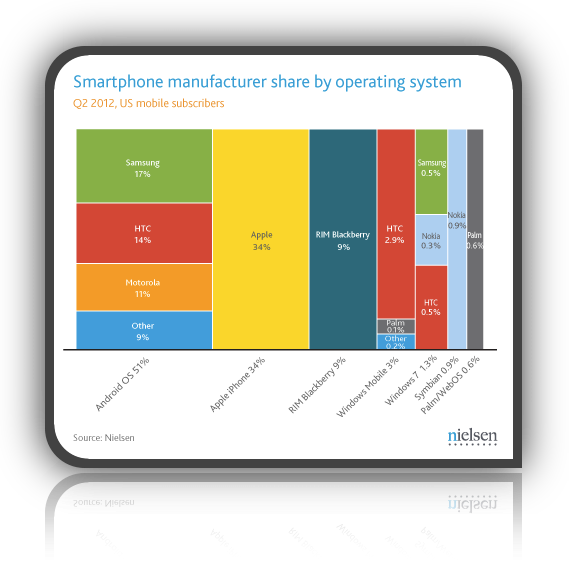

Apple doubles its nearest Android competitor in market share

If you look at the chart below from Nielsen, you’ll see that Android has 51.8 percent of the smartphone market share and Apple has 34.3 percent.

Look at it again. Not a single Android-based smartphone even comes close to Apple’s market share. In fact, Apple doubles its nearest competitor, Samsung, which has 17 percent market share. Also consider that each of those manufacturers have a variety of smartphones available on the market at the same time. Apple has a couple of iPhones.

What are the productivity and survivability implications?

Larger

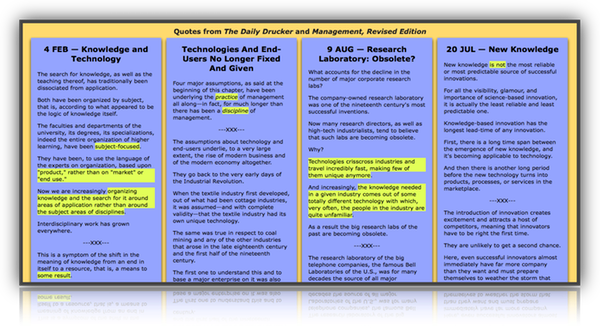

It is the very nature of knowledge

that it changes fast and

that today's certainties

will be tomorrow's absurdities. — Peter Drucker

See “economic environment overview” in the preface to Marketing Moves

Looking backwards:

The First Technological Revolution and Its Lessons The First Technological Revolution and Its Lessons

A Century of Social Transformation A Century of Social Transformation

|

![]()