A Society of Organizations

The following pages have overlapping content that needs to be consolidated.

Knowledge ::: society of organizations ::: management Knowledge ::: society of organizations ::: management

Society of Organizations Society of Organizations

Management Management

CEO work area landscapes (in limbo) CEO work area landscapes (in limbo)

Major life directions: what do you want to be remembered for? Major life directions: what do you want to be remembered for?

Within the life span of today's old-timers, our society has become a "knowledge society," a "society of organizations," and a "networked society."

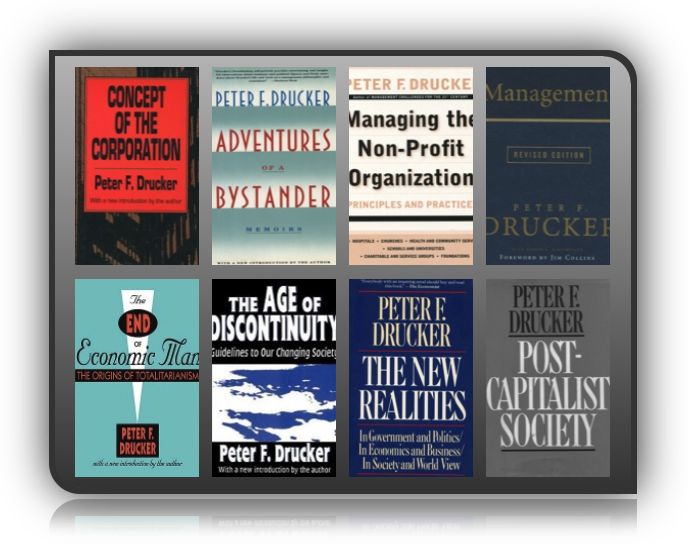

See to The End of Economic Man: The Origins of Totalitarianism

What do YOU want to be remembered for?

SOCIETY in this century has become a society of organizations.

See Post-Capitalist Society

Social tasks which only a century ago were done by the family, in the home, in the shop, or on the farm—from providing goods and services to education and care of the sick and the elderly—are increasingly performed in and through large organizations.

These organizations—whether business enterprises, hospitals, schools, or universities—are designed for continuity and run by professional managers.

Executives have thus become the leadership groups in our society.

The leadership groups of old—whether nobles, priests, landed aristocracy, or business tycoons—have disappeared or become peripheral.

The first job of the executive is to make his organization perform.

Results are always on the outside.

There are only costs on the inside.

Even the most efficient manufacturing plant is still a cost center until a distant customer has paid for its products.

The executive thus lives in a constant struggle to keep performance from being overtaken by the concerns of the inside, that is by bureaucracy.

Business at least stands under the control of the market, which forces even the most powerful corporation to subordinate its inside concerns to outside results and to performance.

But in the public service institution, where the market test is absent—and in many cases cannot even be simulated—bureaucracy constantly threatens to swallow up performance.

For the business enterprise in a market system we are gradually developing a discipline of entrepreneurship, that is, of performance.

But even the President of the United States fights a losing battle to preserve his capacity to give political leadership and to make political decisions in the face of the need to manage an unmanageably large, unmanageably complex, and self-centered bureaucratic machine.

The art and discipline of entrepreneurship to make organizations perform and to produce results will therefore be a continuing concern.

This concern will involve the public service institution as well as the business enterprise.

The executive as a person—as a key individual in society and as a member of his organization—becomes a matter of increasing importance.

Middle managers and other professionals working as individual contributors—as engineers, as chemists, as accountants, as computer programers, as medical technologists, and so on—have constituted the fastest-growing group in American society, and indeed in the society of all developed countries.

Careers in organizations—that is, careers as managers and other professionals—are the principal career opportunities for educated people.

Nine out of ten youngsters who receive a college degree can expect to spend all their working lives as managerial or other professional employees of institutions.

Social theorists and political scientists still, by and large, divide the world into “bosses” and “working stiffs.”

But this was the reality of the nineteenth century.

The reality of today consists of people who are “bosses” but who also have bosses of their own; who are not “capitalists” but who collectively—through their pension funds and their savings—own the economy; people who consider themselves “professionals” but who are also “employees” as “professionals” traditionally were not supposed to be.

The Changing World of the Executive

The knowledge society into which we are moving so fast is going to be a society of organizations.

But of organizations—plural—that will be diverse, decentralized, multiform.

And within these organizations, we are moving away from the standardized, uniform structures that were generally accepted in public administration and business management, “the one right structure for the typical manufacturing company,” for instance, or the “model government agency.”

We are moving toward organic design, informed by mission, purpose, strategy, and the environment, both social and physical—the design I began to advocate forty years ago in The Practice of Management (which came out in 1954). … — Adventures of a Bystander

Larger

From Analysis to Perception — The New Worldview

“Small is beautiful” is, of course, as much stifling dogma as “big is best”—and equally stupid, as one look at the diversity of God’s creation will show. — Adventures of a Bystander

The Function Of Organizations

The function of organizations is to make knowledges productive. Organizations have become central to society in all developed countries because of the shift from knowledge to knowledges.

The more specialized knowledges are, the more effective they will be. The best radiologists are not the ones who know the most about medicine; they are the specialists who know how to obtain images of the body's inside through X-ray, ultrasound, body scanner, magnetic resonance. The best market researchers are not those who know the most about business, but the ones who know the most about market research. Yet neither radiologists nor market researchers achieve results by themselves; their work is “input” only. It does not become results unless put together with the work of other specialists.

Knowledges by themselves are sterile. They become productive only if welded together into a single, unified knowledge. To make this possible is the task of organization, the reason for its existence, its function.

Peter Drucker, Post-Capitalist Society

In the knowledge society, it is not the individual who performs.

The individual is a cost center rather than a performance center.

It is the organization that performs. (Across multiple time dimensions: explore the life stories of HP, Kodak, RIM or RCA) — A Century of Social Transformation by Peter Drucker

Larger

It is the very nature of knowledge

that it changes fast and

that today's certainties

will be tomorrow's absurdities. — Peter Drucker

Because the knowledge society

perforce has to be

a society of organizations,

its central and distinctive organ is

management.

When we first began to talk of management, the term meant “business management” — since large-scale business was the first of the new organizations to become visible.

But we have learned this last half-century that management is the distinctive organ of all organizations.

All of them require management—whether they use the term or not.

All managers do the same things whatever the business of their organization.

All of them have to bring people—each of them possessing a different knowledge—together for joint performance.

All of them have to make human strengths productive in performance and human weaknesses irrelevant.

All of them have to think through what are “results” in the organization—and have then to define objectives.

Management by Objectives — a user's guide

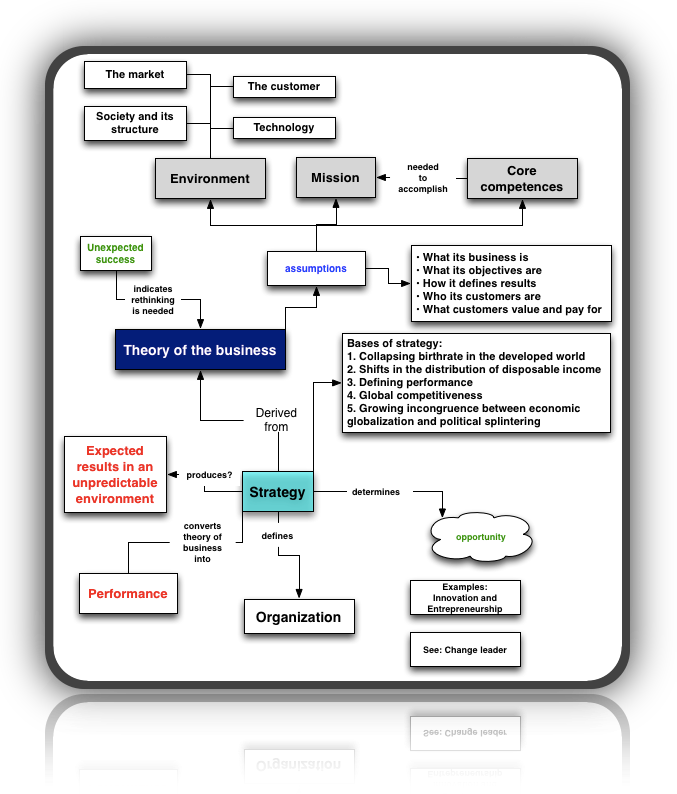

All of them are responsible to think through what I call the “theory of the business,” that is, the assumptions on which the organization bases its performance and actions, and equally, the assumptions which organizations make to decide what things not to do.

Communicate and Test Assumptions

The theory of the business must be known and understood throughout the organization.

This is easy in an organization’s early days.

But as it becomes successful, an organization tends increasingly to take its theory for granted, becoming less and less conscious of it.

Then the organization becomes sloppy.

It begins to cut corners.

It begins to pursue what is expedient rather than what is right.

It stops thinking.

It stops questioning.

It remembers the answers but has forgotten the questions.

The theory of the business becomes “culture.”

But culture is no substitute for discipline, and the theory of the business is a discipline.

The theory of the business has to be tested constantly.

It is not graven on tablets of stone.

It is a hypothesis.

And it is a hypothesis about things that are in constant flux—society, markets, customers, technology.

And so, built into the theory of the business must be the ability to change itself.

Some theories are so powerful that they last for a long time.

Eventually every theory becomes obsolete and then invalid.

It happened to the GMs and the AT&Ts.

It happened to IBM.

It is also happening to the rapidly unraveling Japanese keiretsu.

4 JUL The Daily Drucker

All of them require an organ that thinks through strategies, that is, the means through which the goals of the organization become performance.

All of them have to define the values of the organization, its system of rewards and punishments, and with its spirit and its culture.

In all of them, managers need both

the knowledge of management as work and discipline,

and

the knowledge and understanding of the organization itself

its purposes,

its values,

its environment and markets,

its core competencies.

— A Century of Social Transformation by Peter Drucker

Purpose and Objectives First

To Drucker, strategy, like everything else in management, is a thinking person’s game.

It isn’t arrived at by following some rigid set of rules but by thinking through various aspects of the business.

It all starts with objectives.

Management by Objectives — a user's guide

“Only a clear definition of the mission makes possible clear and realistic business objectives.

It is the foundation for priorities, strategies, plans and work assignments.

It is the starting point for the design of managerial jobs, and, above all, for the design of managerial structures.

Structure follows strategy.

Strategy determines what the key activities are in a given business.

And strategy requires knowing what our business is and what it should be.”

Drucker also explained that “nothing may seem simpler or more obvious than to answer what a company’s business is.

A steel mill makes steel, a railroad runs to carry freight and passengers … .

Actually ‘what is our business?’ is almost always a difficult question which can be answered only after hard thinking and studying.

And the right answer is usually anything but obvious.”

Thinking back to Drucker’s Law, no strategy can be created without the customer, for it is the customer who defines business purpose.

And “therefore the question ‘what is our business?’ can be answered only by looking at the business from the outside, from the point of view of the customer and the market.

What the customer sees, thinks, believes and wants at any given time must be accepted by management as an objective fact deserving to be taken as seriously” as any hard data collected from salespeople, accountants, or engineers, contended Drucker.

Drucker claimed that the single most important cause of business failure can be attributed to management’s failure to ask the question “what is our business?” in a “clear and sharp form.”

And it isn’t only when a company is starting out that the question should be asked, or when the company is in trouble.

“On the contrary,” Drucker wrote, “to raise the question and to study it thoroughly is most needed when a business is successful.

For then failure to raise it may result in rapid decline.”

— Inside Drucker's Brain

A product or service name is never an effective answer to these questions because it doesn’t specify the specific contribution to the customer that matches what customers value and pay for — they buy what it does for them. See “The Customer: Joined at the Hip” in The Definitive Drucker and “Changing Values and Characteristics (creating a customer)” in Innovation and Entrepreneurship — bobembry

The view of management presented above is the opposite of inside-out behavior …

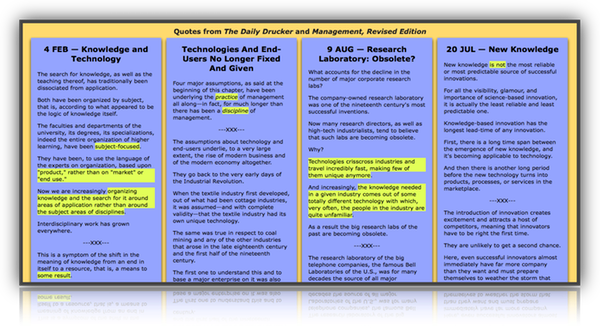

AS WE ADVANCE deeper into the knowledge economy, the basic assumptions underlying much of what is taught and practiced in the name of management are hopelessly out of date. (calendarize this?)

Amazon link: How The Mighty Fall

Only the Paranoid Survive

… the organization of the post-capitalist society of organizations

is a destabilizer.

Because its function is to put knowledge to work

—on tools, processes, and products;

on work;

on knowledge itself—

it must be organized for constant change.

It must be organized for innovation;

and innovation,

as the Austro-American economist

Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950) said,

is “creative destruction.”

It must be organized for systematic abandonment

of the established, the customary, the familiar,

the comfortable

— whether products, services, and processes,

human and social relationships, skills,

or organizations themselves.

It is the very nature of knowledge

that it changes fast and

that today's certainties

will be tomorrow's absurdities. — Peter Drucker

Without the institution, there would be no management.

But without management, there would be only a mob rather than an institution.

The institution is itself an organ of society and exists only to contribute a needed result to society, the economy, and the individual.

Organs, however, are never defined by what they do, let alone by how they do it.

They are defined by their contribution.

And it is management that enables the institution to contribute.

Management is tasks.

Management is a discipline.

But management is also people.

Every achievement of management is the achievement of a manager.

Every failure is a failure of a manager.

People manage rather than “forces” or “facts.”

The vision, dedication, and integrity of managers determine whether there is management or mismanagement.

Management and managers are the specific need of all institutions, from the smallest to the largest.

They are the specific organ of every institution.

They are what holds it together and makes it work.

None of our institutions could function without managers.

And managers do their own job—they do not do it by delegation from the owner.”

The need for management does not arise just because the job has become too big for any one person to do alone.

Managing a business enterprise or a public-service institution is inherently different from managing one's own property or from running a practice of medicine or a solo law or consulting practice.

Of course, many a large and complex enterprise started from a one-man shop. (think organization evolution)

But beyond the first steps, growth soon entails more than a change in size.

At some point (and long before the organization becomes even “fair-sized”), size turns into complexity.

At this point “owners” no longer run “their own” businesses even if they are the sole proprietors.

They are then in charge of a business enterprise—and if they do not rapidly become managers, they will soon cease to be “owners” and be replaced, or the business will go under and disappear.

For at this point, the business turns into an organization and requires for its survival different structure, different principles, different behavior, and different work.

It requires managers and management.

Legally, management in the business enterprise is still seen as a delegation of ownership.

But the doctrine that already determines practice, even though it is still only evolving in law, is that management precedes and even outranks ownership.

The owner has to subordinate himself to the enterprise’s need for management and managers.

There are, of course, many owners who successfully combine both roles, that of owner-investor and that of top management.

But if the enterprise does not have the management it needs, ownership itself is worthless.

And in enterprises that are big or that play such a crucial role as to make their survival and performance matters of national concern, public pressure or governmental action will take control away from an owner who stands in the way of management.

Thus the late Howard Hughes was forced by the United States government in the 1950s to give up control of his wholly owned Hughes Aircraft Company, which produced electronics crucial to U.S. defense.

Managers were brought in because he insisted on running the company as “owner.”

Similarly the German government in the 1960s put the faltering Krupp company under autonomous management, even though the Krupp family owned 100 percent of the stock.

The change from a business that the owner-entrepreneur can run with “helpers” to a business that requires management is a sweeping change.

It requires the application of basic concepts, basic principles, and individual vision to the enterprise.

One can compare the two kinds of business to two different kinds of organism: the insect, which is held together by a tough, hard skin, and the vertebrate animal, which has a skeleton.

Land animals that are supported by a hard skin cannot grow beyond a few inches in size.

To be larger, animals must have a skeleton.

Yet the skeleton has not evolved out of the hard skin of the insect; for it is a different organ with different antecedents.

Similarly, management becomes necessary when an organization reaches a certain size and complexity.

But management, while it replaces the “hard-skin” structure of the owner-entrepreneur, is not its successor.

It is, rather, its replacement.

When does a business reach the stage at which it has to shift from “hard skin” to “skeleton"?

The line lies somewhere between 300 and 1,000 employees in size.

More important, perhaps, is the increase in complexity.

When a variety of tasks all have to be performed in cooperation, synchronization, and communication, an organization needs managers and management.

One example would be a small research lab in which twenty to twenty-five scientists from a number of disciplines work together.

Without management, things go out of control.

Plans fail to turn into action.

Or worse, different parts of the plans get going at different speeds, different times, and with different objectives and goals.

The favor of the “boss” becomes more important than performance.

At this point the product may be excellent, the people able and dedicated.

The boss may be—and often is—a person of great ability and personal power.

But the enterprise will begin to flounder, stagnate, and soon go downhill unless it shifts to the “skeleton” of managers and management structure. (calendarize this?)

The word “management” is centuries old.

Its application to the governing organ of an institution and particularly to a business enterprise is American in origin.

“Management” denotes both a function and the people who discharge it.

It denotes a social position and authority, but also a discipline and a field of study.

Even in American usage, “management” is not an easy term, for institutions other than business do not always speak of management or managers.

Universities or government agencies have administrators, as have hospitals.

Armed services have commanders.

Other institutions speak of executives, and so on.

Yet all these institutions have in common the management function, the management task, and the management work.

All of them require management.

And in all of them, management is the effective, the active organ.

What is a business?

To know what a business is, we have to start with its purpose.

Its purpose must lie outside of the business itself.

In fact, it must lie in society, since business enterprise is an organ of society.

There is only one valid definition of business purpose: to create a customer.

Markets are not created by God, nature, or economic forces but by executives.

The want a business satisfies may have been felt by the customer before he was offered the means of satisfying it.

Like food in a famine, it may have dominated the customer's life and filled all his waking moments, but it remained a potential want until the action of businessmen converted it into effective demand.

Only then is there a customer and a market.

The want may have been unfelt by the potential customer; no one knew that he wanted a photocopier or a computer until these became available.

There may have been no want at all until business action created it—by innovation, by credit, by advertising, or by salesmanship.

In every case, it is business action that creates the customer.

It is the customer who determines what a business is.

It is the customer alone whose willingness to pay for a good or for a service converts economic resources into wealth, things into goods.

What the customer buys and considers value is never a product.

It is always utility, that is, what a product or a service does for him.

Because its purpose is to create a customer, the business enterprise has two—and only these two—basic functions: marketing and innovation. (calendarize this?)

Despite the emphasis on marketing and the marketing approach, marketing is still rhetoric rather than reality in far too many businesses.

Consumerism proves this.

When managers speak of marketing, they usually mean the organized performance of all selling functions.

This is still selling.

It still starts out with “our products.”

It still looks for “our market.”

True marketing starts out the way Marks & Spencer starts out, with the customer, his demographics, his realities, his needs, his values.

It does not ask, “What do we want to sell?”

It asks, “What does the customer want to buy?”

It does not say, “This is what our product or service does.”

It says, “These are the satisfactions the customer looks for, values and needs.

Marketing alone does not make a business enterprise.

In a static economy, there are no business enterprises.

There are not even executives.

The middleman of a static society is a broker who receives his compensation in the form of a fee, or a speculator who creates no value.

A business enterprise can exist only in an expanding economy, or at least in one that considers change both natural and acceptable.

And business is the specific organ of growth, expansion, and change.

The second function of a business is, therefore, innovation—the provision of different economic satisfactions.

It is not enough for the business to provide just any economic goods and services; it must provide better and more economic ones.

It is not necessary for a business to grow bigger; but it is necessary that it constantly grow better.

… Social problems, such as a deteriorating educational system, by contrast, are dysfunctions of society rather than impacts of the organization and its activities.

Since the institution can exist only within the social environment and is indeed an organ of society, such social problems affect the institution.

They are of concern to it even if … the company had no role in producing the decline in the education system.

A healthy business, a healthy university, a healthy hospital cannot exist in a sick society.

Management has a self-interest in a healthy society, even though the cause of society's sickness is not of management's making. (calendarize this?)

Management, Revised Edition

What do customers value?

The question, What do customers value?—what satisfies their needs, wants, and aspirations—is so complicated that it can only be answered by customers themselves.

And the first rule is that there are no irrational customers.

Almost without exception, customers behave rationally in terms of their own realities and their own situation. (Their logic bubble — see below)

Leadership should not even try to guess at the answers but should always go to the customers in a systematic quest for those answers.

I practice this.

Each year I personally telephone a random sample of fifty or sixty students who graduated ten years earlier.

I ask, “Looking back, what did we contribute in this school?

What is still important to you?

What should we do better?

What should we stop doing?”

And believe me, the knowledge I have gained has had a profound influence.

What does the customer value? may be the most important question.

Yet it is the one least often asked.

Nonprofit leaders tend to answer it for themselves.

“It’s the quality of our programs.

It’s the way we improve the community.”

People are so convinced they are doing the right things and so committed to their cause that they come to see the institution as an end in itself.

But that’s a bureaucracy.

Instead of asking, “Does it deliver value to our customers?” they ask, “Does it fit our rules?”

And that not only inhibits performance but also destroys vision and dedication.

— Peter Drucker,

The Five Most Important Questions …

Quality

Quality in a product or service is not what the supplier puts in.

It is what the customer gets out and is willing to pay for.

A product is not quality because it is hard to make and costs a lot of money, as manufacturers typically believe.

This is incompetence.

Customers pay only for what is of use to them and gives them value.

Nothing else constitutes quality.

— Peter Drucker

The Logic Bubble

I (Edward de Bono) created the term ‘logic bubble’ in a previous book.

When someone does something you do not like or with which you do not agree, it is easy to label that person as stupid, ignorant or malevolent.

But that person may be acting ‘logically’ within his or her ‘logic bubble’.

That bubble is made up of the perceptions, values, needs and experience of that person.

If you make a real effort to see inside that bubble and to see where that person is ‘coming from’, you usually see the logic of that person’s position.

In the school programme for teaching thinking (CoRT (Cognitive Research Trust) programme) there are tools which broaden perception so the thinker sees a wider picture and acts accordingly.

One of these tools is OPV, which encourages the thinker to ‘see the Other Person’s Point of View’.

We have numerous examples where a serious fight came to a sudden end when the combatants (who had learned the methods) decided to do an OPV on each other, a very similar process to understanding the ‘logic bubble’ of the other party.

— Edward de Bono

Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything (P.S.)

Communications

The 90/10 Rule at Yum! Brands

But every analysis of actual allocation of resources and efforts in business that I have ever seen or made showed clearly that the bulk of time, work, attention, and money first goes to 'problems' rather than to opportunities, and, secondly, to areas where even extraordinarily successful performance will have minimal impact on results. (calendarize this?)

One of the hardest things for a manager to remember is that of the 1,000 different situations he or she will be asked to deal with on any given day, only the smallest handful have a shot at moving the enterprise forward in a truly significant way (calendarize this?)

The job of management, then, is to make sure that financial capital, technology, and top talent are deployed where most of the results are and where most of the costs aren't. The temptation often exists, however, to do exactly the opposite

More about organizations:

‘What do you want to be remembered for?’

Society of organizations table

CEO

There is a Google site search tool at the bottom of the page. Try "society of organizations"

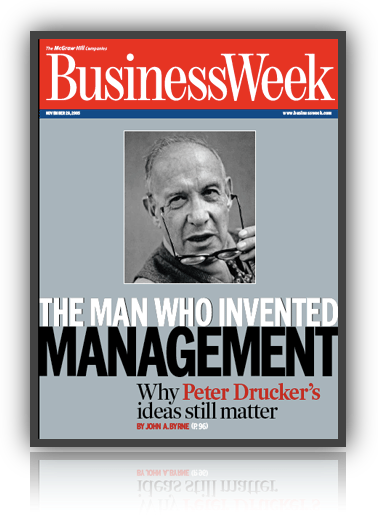

Peter Drucker: Conceptual Resources

The Über Mentor

A political / social ecologist

a different way of seeing and thinking about

the big picture

— lead to his top-of-the-food-chain reputation

about Management (a shock to the system)

“I am not a ‘theoretician’; through my consulting practice I am in daily touch with the concrete opportunities and problems of a fairly large number of institutions, foremost among them businesses but also hospitals, government agencies and public-service institutions such as museums and universities.

And I am working with such institutions on several continents: North America, including Canada and Mexico; Latin America; Europe; Japan and South East Asia.” — PFD

List of his books

Large combined outline of Drucker’s books — useful for topic searching.

“High tech is living in the nineteenth century,

the pre-management world.

They believe that people pay for technology.

They have a romance with technology.

But people don't pay for technology:

they pay for what they get out of technology.” —

The Frontiers of Management

List of topics in this Folder

TLN Keywords:

|

![]()