Drucker on Asia:

A dialogue between

Peter Drucker and Isao Nakauchi

Amazon link: Drucker on Asia: A dialogue between Peter Drucker and Isao Nakauchi

From Publishers Weekly

There are no underdeveloped countries anymore, only mismanaged ones, declares bestselling management thinker Drucker in this series of conversations, letters and faxes exchanged in 1994-1995 with Japanese retail mogul Nakauchi.

Drucker, who dominates their dialogue, emphasizes that developing nations don’t need government-to-government aid or grandiose World Bank projects but, instead, partnerships with private enterprises in industrial nations.

Nakauchi discusses the problems of doing business in China and stresses that Japan urgently needs to amend its conformist educational system as well as its industrial structure to foster innovation, entrepreneurship and creativity.

Their wide-ranging talks, broken up by subheads for easy reference, briefly touch on a multitude of topics, from ways to reconstruct and revitalize an enterprise to the failure to stop nuclear proliferation.

Drucker offers unusually candid autobiographical asides here but spends too much time on commonplace observations and themes familiar to readers of his previous books.

Copyright 1996 Reed Business Information, Inc.

From Booklist

The focus of attention on the Pacific Rim has been diffused recently by a faltering Japan, by the ascendancy of such countries as Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia, and by the prospect of a Hong Kong under Chinese control.

Nonetheless, it is clear that Japan will continue to dominate economically.

Those interested in the future prospects of Asia and disappointed by John Naisbitt’s overgeneralized, readily apparent views in Megatrends Asia (1996) will be better served by this series of conversations between Drucker and the man sometimes called “the Sam Walton of Japan.”

Nakauchi is a maverick in his own country; he is the largest retailer in Japan and solved the problem of Japan’s convoluted and costly distribution system by building his own trucking fleet.

Based on exchanges that took place over a two-year period beginning in 1994, this “dialogue” between Drucker and Nakauchi looks at the role of China, the prospects of a “borderless world,” and the impact of the “knowledge society.” — David Rouse

See all Editorial Reviews

Contents of Drucker on Asia - A Dialogue Between Peter Drucker and Isao Nakauchi

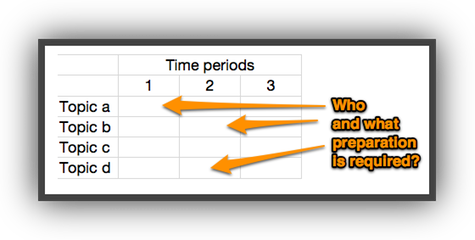

Which topics below and how would you calendarize?

- Preface (below)

- Part I Times of Challenge

- 1 The challenges of China

- What is the future for China’s huge market?

- China offers greater dangers than any other market … and opportunities too great to be ignored

- Growing Coastal China

- From ‘triad’ to multi-centric world economy

- Developed countries suffering with ‘flu

- Shifts in the balance of economic power

- A multi-centric world

- Secrets of Chinese management

- Overseas Chinese

- An example of a company run by people of Chinese extraction

- Investment in ‘invisible infrastructure’

- A shortage of educated people

- Higher education in China

- Confucians in the modern world

- Optimism … China’s potential as an organisation of autonomous regions

- ‘Bubble economy’ in China

- The issue of Deng Xiaoping’s succession

- Inflation and social upheaval

- Unemployment in state-owned enterprises

- The dilemma of Chinese government

- Peasants without work

- Great chance and great risk

- A risk one cannot afford not to take

- The greatest market opportunities

- Dangers of nuclear war

- Only the development of invisible infrastructures will bring prosperity to China and that development is our task

- Encouragement of the answer ‘No’

- Attractions of the Chinese market

- The future that is already here

- Expansion of the production base is not enough

- Improvement of the ‘invisible infrastructure’

- The decision to expand into China

- The mission of an entrepreneur

- Only distribution-led economic development can create the human resources which China needs more than anything else

- People, not money, develop an economy

- Distribution in China

- 2 The challenges of a borderless world

- ‘Hollowing out’ of Japanese industry, Japan’s role in a borderless world, economic blocs

- Japan’s role in Asia

- The ‘hollowing out’ of Japanese industry and the borderless world

- Interference by governments

- There is no need for pessimism over the Japanese economy

- Japan flies not on ‘one wing’, but on ‘two wings’

- Baseless pessimism over the Japanese economy

- Services as a growth sector

- Great work in the retail business

- Finance as the high-tech frontier

- Fallacies about ‘hollowing out’

- 1. The separation of production and employment

- Instead of automation

- Transition in manufacturing

- 2. The influence of a weak dollar on the Japanese economy

- 3. Investment overseas and exports

- Creating new markets in developing countries

- 4. The competitive advantage of low-wage countries

- The reducing importance of wage competition

- Changes in US businesses

- An empty theory of politicians in the United States

- A big problem - dislocation of the work force

- The responsibility of employers

- Developing countries don’t need government-to-government aid, but

- Failure in development aid

- Private sector initiative

- Management has to learn to balance the three dimensions - global, regional and local

- The borderless world

- Localization

- EU and NAFTA

- Globalized top management

- Regional integration in today’s world

- Regionalization in Asia

- Globalization, regionalization and localization

- Challenges for executives

- Knowledge plays an important role in changing industrial structures

- ‘Hollowing out’ and changing industrial structure

- Redesigning business

- Convenience store chains

- Supporting the development of human resources

- Problems of regionalism

- The responsibility of employment

- The importance of education

- Developing one’s strength

- 3 The challenges of the ‘knowledge society’

- Present educational systems cannot develop talent for the ‘knowledge society’

- The Japanese educational system itself is not wrong. Japan has its own forms of creativity and originality

- Problems imposed from outside the education system

- Individuality in Japanese arts

- Individuality in Japanese company and university

- Experience within Japanese schools

- Student against student

- Leading universities and careers into the top echelon

- Plutocracy in education

- Universities before World War II

- An explosion in university attendance

- ‘Examination hell’ and the desire to innovate

- Constraining entrepreneurial spirit

- Japanese creativity and originality

- Continued learning is essential in the knowledge society

- Computers and education

- Separating learning and teaching

- Computers and the transformation of schools

- Needs of continuing education

- What is an educated person?

- Young people not knowing how to connect their knowledge

- Knowledge and human development

- Now I have hope for young people who can innovate

- Pessimism about Japanese creativity

- Lack of a sense of self-responsibility

- A truly educated person

- Responsibility of executives

- Expectation of future generations

- What changes will information technology bring to society, the economy and private enterprises?

- The effects of information technology

- Convenience stores present an example of the information-based organization of tomorrow

- The effects of information technology

- Information needed by executives

- The superfluous kacho

- Autonomous organizational units

- Radical change in the organization

- Decentralization of work

- Working at home and the satellite office

- The cohesion of tomorrow’s organization

- An unpredictable future for office city

- Impact of information on one’s way of life

- What information technology adds to the old ways

- Developments in IT will transform every worker into an executive

- The impact of information technology

- Creation of the ‘executives of tomorrow’

- 4 The challenges for entrepreneurship and innovation

- The entrepreneur’s role in society is to bring innovation

- Necessary conditions for innovation

- Roles for entrepreneurs

- I am confident that a third ‘economic miracle’ will happen in Japan

- The effect of ‘creative imitation’

- Decline of entrepreneurship

- Two parallel needs concerning entrepreneurship

- How to organize for entrepreneurship and innovation

- Young people are required

- Innovators do not work in a team

- Role of pioneers

- The years of tremendous change

- ‘Creation of customers’ will be an eternal challenge

- The ‘creative imitation’ of Japanese companies

- New materials

- After the experience in the jungle

- The message of John F. Kennedy

- Wisdom learned from America

- Drucker’s suggestions

- Service to consumers and society

- 5 Appendix to Part I: Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995

- A thoughtful letter that fateful morning

- Establishing an Emergency Management Center

- Making full efforts toward recovery

- Importance of distribution in a disaster area

- Confusion caused by lack of information

- Reconstruction led by the private sector

- Part II Time to Reinvent

- 6 Reinventing the individual

- Japan urgently needs to reinvigorate ordinary people and make them more effective

- Reinvigorating individuals in the organization

- Efforts of individuals to be effective

- Knowledge people must take responsibility for their development and placement

- How to cause changes

- ‘The Awareness of change’ has changed

- The first change—social mobility

- The second change—knowledge rather than skill

- The third change—needs of ‘reinventing’

- Balance between change and continuity

- Revitalizing oneself

- Drucker’s seven experiences

- Work as a trainee in an export firm

- The first experience—taught by Verdi

- ‘Striving for perfection’—goal and vision

- The second experience—taught by Phidias

- Work as a journalist

- The third experience—developing own method of studying

- The fourth experience—taught by the editor-in-chief

- Reviewing the preceding year

- The fifth experience—taught by the senior partner

- What is necessary to be effective in a new assignment

- The reason for sudden incompetence

- Requirement for success

- The sixth experience—taught by the Jesuits and the Calvinists

- Importance of writing down

- The seventh experience—taught by Schumpeter

- The same things are learned by successful people

- Doing a few simple things

- Responsibility for one’s own development and placement

- Executives can affect people’s lives

- Responsibility of executives

- The Nakauchi experiences

- Asking customers’ needs

- A little innovation

- A new store in Sannomiya, Kobe

- Beef for 39 yen

- Cessation of supplies

- Sales of packed meat

- Orange juice and the strategy of low pricing

- The first lesson—’Innovation means parting with convention’

- The second lesson—importance of adopting the perspective of the consumer

- The third lesson—corporate philosophy and continuous learning

- 7 Reinventing business

- How to design an organization structure that can revitalize a company?

- Responsibility of corporations

- Without an effective mission statement, there will be no performance

- The short life-span of the business enterprise

- The need to change the university

- The need to change government

- Victims of success

- Fortune’s top 500 companies

- The threat of continuing success

- An example of an automobile company

- Mission and its importance

- The role of the mission statement

- Financial results are not the purpose

- Competitive cost of living

- A true merchant

- Ability to convert change into opportunity

- Welcoming change

- Organized abandonment

- ‘Five Deadly Business Sins’

- System for organized innovation

- Concept of mission

- The very reason for the existence of a company is to turn what is learned immediately into action, thus contributing to society

- The customer determines the price

- 8 Reinventing society

- Converting organizations into social entities that contribute to society can protect society from degeneration

- Destiny of advanced nations

- Corporations and nonprofit organizations

- There is need for a social sector to rebuild community

- Collapse of the Roman Empire

- Collapse of the Chinese civilization

- Collapse of the Ottoman Empire

- The philosophy of Arnold Toynbee

- The lesson of the Meiji era

- Meiji already established by Bunjin

- Education by Bunjin

- Bunjin as a ‘social sector’

- Rebuilding the community

- Through volunteer work in the social sector, one can regain citizenship

- What government cannot do

- The role of business

- The role of the social sector

- The purpose of institutions of the social sector

- Management

- Restoration of citizenship

- Change of families

- Change of village and town

- New community

- Meaning of citizenship

- What can the community do for me?

- Meaning of citizenship

- What business can learn

- Managing knowledge workers as volunteers

- Historical background

- Community in business enterprises

- New organization

- What this means for Japan

- Each of us must endeavour to influence and change our society based on the principles of self-offering, self-discipline and self-responsibility

- Self-offering, self-discipline and self-responsibility

- Change by wisdom

- Seeds of change—dedication of volunteers

- Information and the local community

- Daiei and Recruit

- 9 Reinventing government

- What are your views on government regulation and the role of government in a free market? What is your advice on reinventing government?

- Reevaluation of government

- Free market economy

- Regulation and the task of government

- Reinventing of government

- The great strength of the free market is that it minimizes threats and mistakes

- The free market cannot stand alone

- Necessary framework

- Raison d′être of free market

- Realization by Ludwig Ehrhardt

- Mistakes are catastrophic in a planned economy

- Personal responsibility in free market

- Minimization of mistakes

- Legal assurance of property rights

- We need to avoid regulations that are

- The meaning of regulations

- Globalized economy

- Japan’s cost of living and competitiveness

- Companies fleeing California

- Burden and benefit of regulations

- Regulations that are unenforceable

- Control of transnational money flow

- Regulations that have become useless

- Regulation of the airlines

- Meaningless separation of banking from investment banking

- Review of regulations

- Regulations which penalize enterprises and consumers

- The fewer the better

- The initiative has to come from government and its policy has to be transnational

- Small government

- Beyond a single nation

- Money has become transnational

- Free banking

- Transnational issue of the environment

- Horrors of civil war

- Failure of the attempt to stop nuclear proliferation

- Failure of international economic aid

- Needs of economic aid

- The market forces

- Initiative of government

- Old political theory has collapsed. Government has to re-think to transform itself into ‘effective government’

- Global issues are only one part of the challenges to government

- Three-hundred-year old political theories

- Japan and Europe

- The power of bureaucracy

- Japanese government is the most traditional

- Two things required to renew government (Kaizen)

- Benchmarking

- The system of compensation

- Need to re-think organization

- ‘Would we now go into this mission?’

- Wasteful activities

- The US welfare program

- Military aid

- To reform or to abolish

- Great by-product—cost savings

- It seems to be impossible today

- Will it be impossible tomorrow?

- Effective government

- Government must adopt an approach to economic policy that is oriented to the private sector

- Challenges to create a brighter future

- Based on market economies

- Japanese administration

- Systems that should be reformed

- Developing a citizen’s society

- Influence of new Keynesian scholars

- Shift to free market economy based on personal responsibility

- Information for innovation

- Anecdotes of two leaders—Sadaharu Oh

- Anecdotes of a second leader—Arie Selinger

- Developing one’s strength

- The duty of executives

Preface

Peter F. Drucker

I AM WRITING THIS PREFACE on March 11, 1995—ten years to the day since the collapse of Communism and of the Soviet Empire began with Mikhail Gorbachev’s election as the First Secretary of the Communist Party.

The political world has changed beyond all recognition in these ten years.

But, while less dramatic, the changes in the economic world have been fully as great, fully as important, fully as irreversible.

And far too little attention is being paid to them.

Specifically, government has become the storm center of the non-communist world, threatening sudden, unpredictable economic and currency upheavals—the legacy of forty years of failure of the ‘Keynesian Welfare State’ whose theories and policies dominated the Western noncommunist world before 1985.

These threats—and especially the threat of sudden panic and collapse undoing years of hard, steady work on economic development and prosperity such as only a few months ago occurred in Mexico—are by no means confined to developing countries.

Sweden and Italy, to name only two European countries, are equally unstable as a result of government over-spending and over-borrowing.

Even France’s stability is doubtful.

And the US is engaged in a massive last-ditch attempt to cut its government deficit.

While Japan alone of all major countries in the developed world—has not indulged in the reckless expansion of government spending and in under-saving grossly, her government and policies too are in crisis.

Forty years of stability have come to an end.

And no country is as exposed to the shock waves which a collapse of government finance and currencies creates as is Japan—endaka is just a foretaste of what a collapse of the Chinese economy and Chinese currency under the threat of run-away inflation might, for instance, mean to Japan.

Secondly, the structure and the dynamics of the world economy have changed profoundly.

The ‘growth economies’ of the world in the last ten years have not been Japan or the US or Western Europe.

They have been the rapidly developing countries of mainland Asia—with Coastal China in the forefront—and some countries of Latin America which, returning to fiscal rectitude and free markets after years of wild inflation and protectionism, have shown almost explosive (though also very dangerous) growth.

There is no one ‘economic center’ in the world economy any more; the tiny island of Taiwan has now the world’s second-largest foreign-exchange surplus.

And there are no ‘superpowers’.

Japan leads in the development of mainland Asia.

But in the high-tech industries where the real growth is—biotechnology and genetics, information technology, software, the new finance—Japan is still sadly lagging.

The US has put its manufacturing house in order.

Most of US manufacturing industry is now as competitive as that of any other country; even the automotive industry has almost caught up.

And the US has attained an almost unbeatable lead in the new growth industries, and especially in the high-tech industries.

But government finance and the savings rate are in sorry shape.

Western Europe has not been able to exploit the enormous opportunities of economic unification and has fallen badly behind in manufacturing efficiency in all high-tech areas, and in employment.

Thirdly, organization structure and business strategies are in flux.

Information is beginning to affect both, to the point where traditional business organization is becoming obsolete.

But also the traditional concept of the ‘employer’—the company for which people work—is unravelling.

More and more people work as temporaries.

Outsourcing is becoming general.

In outsourcing people work with a company, for example doing its data processing, but do not work for the company, and are not its employees.

In the West—though apparently not yet in Japan—more and more of the most senior and most responsible employees, such as senior researchers, rarely even come to the company’s office any more but work at home or in small office clusters close to where they live.

Fourthly, the work force is changing rapidly.

Blue-collar industrial workers in the mass-production plants were the center of the work force only yesterday.

Today, they are shrinking rapidly in numbers and, even more rapidly, in importance.

Even the people who do the jobs in the plant which the blue-collar worker did yesterday, are increasingly different people.

They are ‘technicians’ with a substantial theoretical knowledge rather than people who get paid for working with their hands or for tending machines.

And at the center of gravity of the work force in every developed country are increasingly knowledge workers, people who do not work with their hands at all but are being paid for what they have learned in school and university.

These people have totally different expectations—of their work; of the way they are being managed; of their opportunities and rewards.

But also the measures that made traditional blue-collar workers productive do not work to make knowledge workers productive.

They pose a different, but no less critical, productivity challenge.

And fifthly, underlying all this is the shift to knowledge as the key resource of production.

What happened in the last ten years is not that free markets and free enterprise won.

Communism and central planning collapsed.

But this only brought out all the more clearly the challenges which free markets and free enterprise now face.

What then does all this mean for an individual country and its economy—and specifically for Japan?

For society?

For the individual company?

And, finally, for the individual, and especially for the individual executive or professional?

These are the questions to which the dialogue between Mr Nakauchi and myself addressed itself.

The dialogue started last Autumn on my most recent visit to Japan.

It was then continued during the Autumn and Winter by letter and fax.

Mr Nakauchi and I share the same concerns, but we tackle them differently: Mr Nakauchi as a Japanese, though one with intimate knowledge of the West; as an entrepreneur who has built and runs the Daiei Company, one of the world’s largest and most successful food retailers; and as a businessman deeply concerned through his leadership in Keidanren (where he is Vice Chairman) with public policy and with society.

I approach the same concerns as a Westerner though as one who knows a little bit about Japan and deeply loves the country.

I am not a ‘theoretician’; through my consulting practice I am in daily touch with the concrete opportunities and problems of a fairly large number of institutions, foremost among them businesses but also hospitals, government agencies and public-service institutions such as museums and universities.

And I am working with such institutions on several continents: North America, including Canada and Mexico; Latin America; Europe; Japan and South East Asia.

Still, a consultant is at one remove from the day-to-day practice—that is both his strength and his weakness.

And so my viewpoint tends more to be that of an outsider.

The two approaches, however, complement each other as Mr Nakauchi and I soon found out.

This dialogue is presented in two parts because that is how it was conducted.

The first part looks at the major developments in economy, society and business.

The second then focuses on the specific challenge of a period of transition such as ours: how to change and renew—oneself as an individual? one’s business? government?

But both parts have in common a conviction that Mr Nakauchi and I share: theory and practice have to go together.

Theory tells us what needs to be done.

Practice then tells us how to do it.

Throughout this dialogue Mr Nakauchi and I have tried to provide both understanding and effective action.

There are many questions a reader will ask which neither of us could answer—we are still in mid-transition.

But I hope that there is enough in this dialogue to enable each reader both to obtain much deeper understanding of our rapidly changing world and effective guidance to his own action, learning, improvement, and growth, and to better performance of his business.

The initiative for this dialogue came from Mr Nakauchi, and so did the formulation of the main questions.

I am deeply grateful to him for the searching thinking that went into his questions and for the foundation for a productive dialogue which his extensive comments laid.

But thanks are due to some other people too, who, during the course of the project, constantly advised and challenged us: to Mr Tatsuo Fukuda, Mr Shinichi Uesaka and Mr Katsuyoshi Saito, respectively Publisher, Editor and Foreign Rights General Manager at Diamond Publishing, Inc. in Tokyo.

The project owes to these three gentlemen a great deal of its cohesion and clarity.

They deserve our and the reader’s thanks.

Peter F. Drucker

Claremont, California

Needs of continuing education

Another change that is predictable, though entirely different, is that a new focus for school and learning is emerging: the continuing education of already-educated adults.

Precisely because knowledge is becoming the central resource of a modern economy, continuous learning is essential.

For knowledge, by its very definition, makes itself obsolete every few years, and then knowledge workers have to go back to school.

They may be store managers and retail buyers, like the ones who attend your marketing university, or physicians, or engineers, but every few years they have to refresh and renew their knowledge.

Otherwise they risk becoming obsolescent.

This will have tremendous impact on the university and on schools.

It will force us to accept the fact that, in the knowledge society, learning is life-long and does not end with graduation.

In fact, that is when it begins.

It will also have tremendous impact on employing institutions

In effect, these are still changes within the system, rather than changes of the system.

What is an educated person?

Your question: ‘What is an educated person?’ goes directly to the meaning of learning, the meaning of education — the essence of the system.

I am afraid, however, that I cannot answer that question.

It is going to be our challenge for the next one hundred years.

In one way, I very much hope that we will be able to maintain the link with tradition and with the past, which is implicit in the traditional definition of an educated person.

The Japanese definition was developed by the Bunjin of the mid-Edo period, and the Western definition was developed by the great educators of Europe’s seventeenth century.

These definitions still largely underlie the education that you and I received.

I do not believe that this, by itself, is enough, for these definitions assume that learning is finite.

They assume that an educated person is somebody who has learned while young, and stopped learning when going to work.

We will now, I think, have to build into our definition what one of the great men of the Meiji period tried to establish.

Yukichi Fukuzawa, truly one of the most important figures of the nineteenth century, strongly believed and preached that an educated person is one who is able and eager to continue learning.

This will be particularly important as more and more young people are likely to start as specialists or, at least, will make their early careers as specialists.

Young people not knowing how to connect their knowledge

A specialist is a knowledgeable person, but he is not automatically an educated person.

An educated person is capable of relating an area of special knowledge to the universe of knowledge and of human experience.

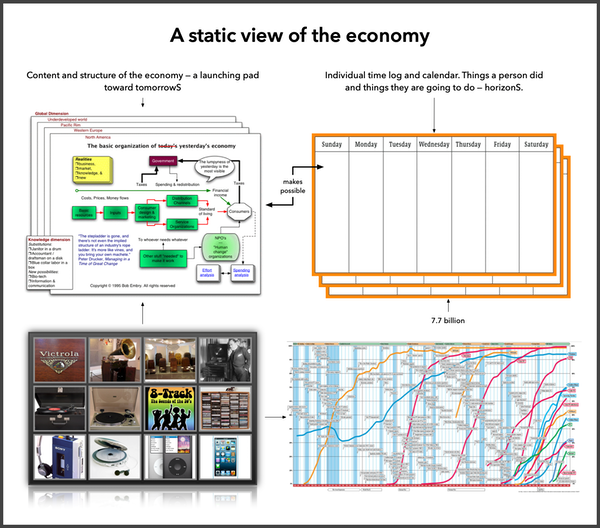

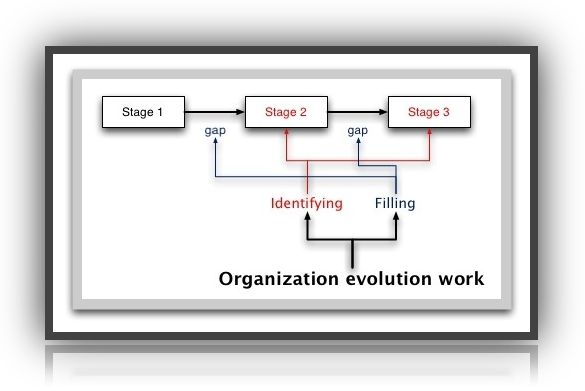

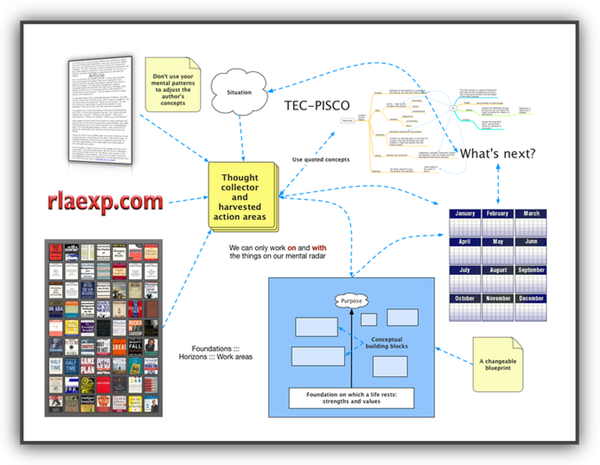

larger composite view ↑ ::: Economic & content and structure ::: Adoption rates: one & two

This, if I may say so, is what today’s younger people are not able to do.

As you know, I teach mostly successful and fairly advanced executives, from business, from government, from non-profit institutions of all kinds—typically men and women in their early or mid forties—who have been successful enough to hold important executive positions, usually in large organizations.

Intelligence trap ::: Logic bubble

They know a great deal, but they do not know that they know it.

They cannot, for instance, relate something they know about economics to their own work.

They cannot relate what they know about their own work to any other field of knowledge.

They do not know how to connect.

This is just as true of my Japanese students as it is of my American or European students.

These executives are usually brilliant people.

They are sent to our Executive Management Program by their employers because they are highly promising executives.

They have an outstanding educational record as a rule, and ten or fifteen years of successful, practical experience behind them, but they find it difficult to relate their experience to what their colleagues in the classroom tell them about their experiences.

They find it difficult to relate what they have learned, let us say, about psychology, to their own work in managing people.

Knowledge and human development

Such people know a great many things, but they are not educated in the sense that they can reflect this knowledge on their own work or development, their own personality.

This, I submit, is the great challenge ahead of us, for the next generation of educational leaders.

Without it, we will have a great deal of specialized competence, but little else.

The challenge ahead of us is to make knowledge again a means to human development.

The challenge is to go beyond knowledge as tools and to recover education as the road to wisdom.

I try to do this in my classroom and with my students.

It is the one reason why I still teach at my age.

Even if I am successful and I have great doubts—I would not know how to teach this to others, let alone how to convert this into a system, a curriculum, an organized educational effort.

This, in a way, is what being an educated person always meant.

This is what Liberal Arts always meant.

It is, in effect, what education, as distinct from knowledge competence, always meant and will, again have to mean.

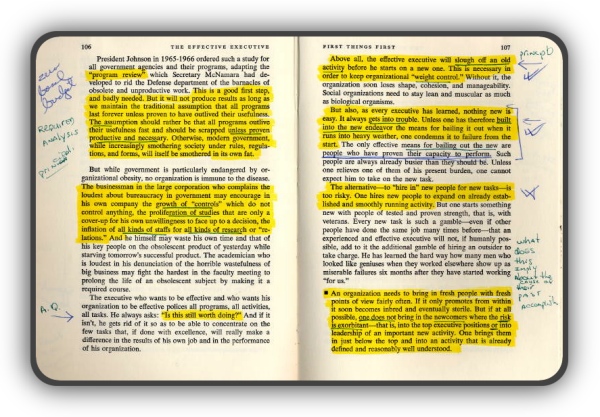

The Effective Executive

Without an effective mission statement,

there will be

no performance — Peter Drucker

Master mission page

The short life-span

of the business enterprise

The Power and Purpose of Objectives:

The Marks & Spencer Story and Its Lessons continue

Where to jump next? ↓

Organizations are human creations and, as such, neither infallible nor immortal.

What Executives Should Remember

Of all organizations, business enterprise is both the one that is most prone to error, and has the shortest life-span.

For business enterprise, by definition and alone among all major organizations of society, is the change-agent.

Danger: the bright idea

All other structures are basically created to conserve and to perpetuate.

Business enterprise, alone, is created both to exploit change in economy and society, and to create change in economy and society.

This makes it, by definition, a far riskier venture than any other major organization.

The actual results of action are not predictable

It also means that it much sooner accomplishes its purpose, if managed superbly well, and will therefore, much sooner than any other institution, disappear or at least become ineffectual.

All human institutions need to balance continuity and change, but in business enterprise, that challenge is ever-present.

The need to change the university

Other major organizations need to change, too, but much less often.

The modern university, for instance, was created almost two hundred years ago in 1809, with the foundation of the University of Berlin amidst the turmoil of the Napoleonic Wars.

For almost two hundred years, the university has remained fundamentally unchanged.

We have added to it, have patched here and mended there.

We have created new additional institutions, such as the technical university and the business school, but we have not fundamentally had to change the university’s design.

Only now, two centuries after its original creation, is it becoming necessary—and rapidly so—to think through again what is the purpose of the university, what is its mission, what should be its structure, and so on.

The need to change government

Government, too, needs change.

In fact, without the ability to change, government degenerates.

There have been literally hundreds of constitutions since the ancient Athenians wrote the first one 2600 years ago.

None of these constitutions survived more than a few short years, at most three or four decades.

The American Constitution has now survived for two hundred years, something for which there is no precedent in history.

It owes its survival to the fact that the Founding Fathers wrote into it provisions for its being changed, and also created in the Supreme Court, an organ specifically designed to adapt the Constitution to changes in society, economy and technology.

However, it is only now, two hundred years after the United States was first founded on a written constitution, that the need to think through the function of government is coming to the fore, as will be discussed a little later in this dialogue.

Victims of success

Very few businesses can prosper even five or seven years without substantial change and massive rethinking of the very concepts on which they are based.

There are exceptions, to be sure, but they are rare.

It is by no means sure that it is a blessing for a business to enjoy long decades of continuity without challenge to its fundamental concepts and assumptions.

There is an old Chinese proverb:

‘Whom the gods want to destroy, they give forty years of success.’

Business history amply proves the wisdom of this old saying.

There are a few businesses around with a basic theory that goes back a century.

There is the universal bank (founded almost simultaneously around 1870 in Germany and in Japan) and the zaibatsu invented by Mitsubishi (and reborn after World War II as keiretsu).

See Management's New Paradigm and Managing in the Next Society

Both concepts are clearly in crisis today, and are rapidly losing their effectiveness.

In the US, the four most successful businesses of this century were, respectively, the Bell Telephone System (AT&T), which alone, of all major telephone systems in the world remained privately-owned and did not become nationalized; Sears Roebuck, for almost half a century the world’s most successful retailer; General Motors; and IBM.

The Bell Telephone System was conceived and designed around 1910 when its predecessor was on the verge of bankruptcy.

Sears Roebuck, as it came to dominate the American retail scene, was designed in the early 1920s, as was General Motors.

And IBM was designed right after World War II.

For seventy years, the Bell Telephone System knew nothing but growth and success.

For more than fifty years, Sears Roebuck and General Motors knew nothing but growth and success.

For forty years, IBM knew nothing but growth and success.

All four looked invincible, but when the time came for them to change, they proved impotent and ineffectual.

They became the victims of their own success.

Fortune’s top 500 companies

Businesses that go unchallenged for long decades are rare exceptions.

The great majority, no matter how successful, need to think through their basic assumptions much sooner.

What executives should remember, Theory of the business and Management’s new paradigm

The great majority, moreover, then find it almost impossible to change.

The business which, after ten years of continuing success, retains the capacity to change and to maintain its effectiveness, is in the minority.

It may not disappear, but it is likely to become an ‘also ran’ and to fall way behind.

The American magazine Fortune has for more than forty years published each year a list of the 500 top manufacturing companies in the US.

During these forty years, one-third of the companies in the original list have disappeared from it altogether — either because they have been liquidated or merged or because they have become insignificant.

Another third has lost position in the list, that is, has dropped from being a major to become a relatively minor business.

Only one-third have maintained themselves in the list, that is, in their position in the American economy.

The threat of continuing success

Every one of these companies that has been able to prosper for four decades has had to change fundamentally.

Yet, the last forty years have been years of great continuity and, generally, years of tremendous prosperity, not only in the American economy but in the world economy.

What is needed is not only the capacity to overcome adversity.

Equally important, and equally needed, is the capacity to take advantage of opportunity, and this, too, is equally threatened by continuing success, threatened by complacency.

An example of an automobile company

The best examples are recent ones.

One is the recent inability of the world’s most successful automobile companies to see, let alone to take advantage of, the sharp shift on the part of the American automobile buyer to sports-utility vehicles, minivans and pick-up trucks.

General Motors should have been the foremost beneficiary.

For when the shift began, in the early 1980s, General Motors had by far the best-designed vehicles of this kind, enjoyed the best reputation in the market, and had the lowest production costs.

Yet, General Motors simply missed the market.

Sports-utility vehicles, mini-vans and pick-up trucks were not considered ‘passenger cars’ and were not included as such in the monthly statistics of automobile sales.

No-one in General Motors’ top management fifteen years ago, therefore, even realized that these ‘non-passenger cars’ were where the market was growing.

But Toyota and Nissan equally missed this opportunity.

By the late 1980s, the Japanese-made automobile had established itself in the American market as the market leader and as the quality standard.

It seemed to be invincible.

Again, because sports-utility vehicles, mini-vans and pickup trucks were not classified as ‘passenger vehicles’, the Japanese missed the market shift in the US just as much as General Motors did.

The opportunity was exploited by the two weaker American automobile companies, Ford and Chrysler, both of which in the mid-1980s, seemed totally unable to compete against either the Japanese or their much bigger American rival.

This explains, by the way, why in the last five years neither General Motors nor the Japanese have been able to grow in the American market three have been losing ground steadily.

Even though all three now have the right products on the market, the three are still steadily losing market share in the American automobile market.

What is probably more important, they are steadily losing their leadership image.

It is, thus, no accident that the management literature has increasingly concerned itself with the management of change and with revitalizing business enterprise.

The first book on these subjects was probably my work Managing For Results in 1964.

Mission and its importance

The management of change is, however, the wrong place to start.

What has to come first is the management of continuity.

Every business enterprise needs to balance continuity and change, and that has to begin with establishing the fundamental direction, that is, with the continuity of the enterprise.

To make a business effective does indeed require that it be able to use change as an opportunity, but this, in turn, requires first that the enterprise have a clear mission.

The section on Business Performance in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices and chapter 9 in Management, Revised Edition

Thinking along a brainroad: when do you have enough radar blips?

The present discussion of the management of change often forgets this.

Without such a mission — that is, without continuity — the enterprise is rudderless and only drifts.

The role of the mission statement

Mr Nakauchi’s statement that the mission of Daiei is

‘to halve the price of commodities by the year 2010’ (10 words)

sounds deceptively simple.

All effective mission statements do.

Yet, like all effective mission statements, it is a call to action rather than pious intention.

It tells the people in the company what their values are, and what effectiveness means for the company and for their own work.

Like all effective mission statements, it makes a team out of what otherwise would be a mob, with each employee doing his or her own work rather than focusing on a common purpose.

Without an effective mission statement, in other words, there will be no performance.

As is the case with Daiei, the effective mission statement is not a statement of financial goals.

They flow from effective performance.

The mission statement has to express the contribution the enterprise plans to make to society, to economy, to the customer.

It has to express the fact that the business enterprise is an institution of society and serves to produce social benefits.

Financial results are not the purpose

Mission statements that express the purpose of the enterprise in financial terms fail inevitably, to create the cohesion, the dedication, the vision of the people who have to do the work so as to realize the enterprise’s goal.

An old saying — going back to ancient Rome, I believe states that ‘Human beings eat to live, but do not live to eat.’

Similarly, enterprises have to have satisfactory financial results to live; without them they cannot survive and cannot, in fact, do their job.

However, they do not exist to have financial results.

Financial results, by themselves, are not adequate, are not the purpose of the enterprise, and are not the justification and reason for its existence.

Competitive cost of living

Implicit in every effective mission statement are clear assumptions regarding the reality in which the enterprise works.

In the case of Daiei’s, I imagine that one underlying assumption is the reality of an increasingly borderless world.

One implication of this is that Japan, in order to be able to compete, must not have higher cost than other developed countries.

The first costs in any economy are not wages.

They are what wages buy, that is, the cost of living.

In that respect, Japan today is not competitive, as you, Mr Nakauchi, have been pointing out for years.

Therefore, the basic assumption underlying Daiei’s mission statement is that Japan’s cost of living has to become competitive, and this is what Daiei is going to bring about.

This is what you mean when you talk about the ‘distribution revolution.’

A second implication of the reality of a borderless world is that Daiei — and any other retailer with whom Daiei competes, whether in Japan or in the US — can and must procure commodities where they can be bought at the lowest price and the highest quality.

This, too, clearly implies a challenge to the present Japanese reality.

A true merchant

Finally, the Daiei statement, like any effective mission statement, makes clear what core competencies the company must have to carry out its mission.

It has to be a truly outstanding merchant — and a merchant is not someone who sells.

A merchant is someone who buys for his customers.

Ability to convert change into opportunity

I have gone into such lengths to discuss the Daiei mission statement for the simple reason that very few businessmen truly understand the importance of a clear mission statement such as Daiei has, and the implications of that mission statement.

Yet, unless there is such clarity, change cannot be managed.

Unless there is such clarity, the executive will not be able to convert change — whether in economy, in technology, in society into business opportunities.

But the ultimate test of management is its ability to do just that.

The ultimate test is not to be able to survive and to be able to cope with change as a threat.

The ultimate test of management is the ability to make change serve the mission of the enterprise — to manage change as an opportunity.

A thought process

Welcoming change

To do this, the first requirement is to build organized abandonment into the business.

It is to be able to keep the enterprise — no matter how big — lean, flexible, and eager to do new things.

There is a great deal of talk today about overcoming ‘resistance to change’.

However, to be able to take advantage of change, enterprises have to welcome change.

They have to consider change as normal rather than as an exception to be feared and to be avoided if at all possible.

They have to be innovative, in other words.

This requires that the enterprise is organized systematically to abandon the outworn and obsolete;

to get rid of things that do not work, no matter how attractive they looked when the enterprise first went into them;

to concentrate resources, especially of competent people, on opportunities, rather than waste them on yesterday’s problems; and

to work together on developing tomorrow rather than on defending yesterday.

Organized abandonment

The first requirement for keeping an enterprise vital and effective is to build into it a systematic policy which subjects every three or four years each product and service, and each policy and procedure, to the question:

‘If we did not already do this, would we now, knowing what we now know, go into it?’

The answer is rarely an unqualified ‘Yes.’

It is often ‘Yes—but we have learned a few things and are now going to do this differently.’

The answer, equally often, will be ‘No.’

Then one asks: ‘What do we do now?’

Maybe all that is needed is to reposition a business, a product, a service.

Maybe it needs to be redesigned.

Maybe it needs to be abandoned.

But unless the enterprise subjects itself to the discipline of organized abandonment, it will not be able to tackle the new.

‘Five Deadly Business Sins’

Without an organized policy of abandonment, enterprises will always feed problems and starve opportunities.

This is the first of what I call the ‘Five Deadly Business Sins’ — and far too many companies indulge in all five.

To be able to remain effective and to manage change and opportunity, however, the other four numbers 2 through 5 — have to be avoided, too.

Number 2 particularly common in American, but also in European business — is the worship of high profit margins and of ‘premium pricing.’

This only benefits the competitor.

Then — number 3 — there is the common sin of mispricing a new product or a new service by pricing it at ‘what the market will bear,’ rather than pricing it on what will create the largest demand, and will satisfy the largest numbers of customers.

Mispricing a product also, in the end, benefits the competitor.

Pricing that is based on one’s costs rather than price-driven costing is the next number 4 — of the deadly business sins.

An effective company starts out with the price that is optimal for the market and then works back to what the costs must be, so that the product or the service can be offered at that price.

This, by the way, is the lesson which the Japanese have taught us in the US and in Europe these last ten or fifteen years.

For price-driven costing, to a large extent, underlies the success of the Japanese in the West.

Finally — number 5 — there is the common sin of slaughtering tomorrow’s opportunity at the altar of yesterday.

It is the sin that underlies the decline of IBM.

It subordinated the new and growing personal computer to the maintenance of the old and declining product, the large mainframe computer.

System for organized innovation

Of course, to remain effective and to be able to exploit change as an opportunity, it is not enough for a business not to do the wrong things.

It has to build organized innovation into its system.

It has to work systematically on looking for change inside and outside.

I have discussed methods of doing this at considerable length in a book that is now ten years old, Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

Businesses stay ahead of competition and both attain and maintain leadership by systematically looking for changes that have already occurred inside and outside, and asking, ‘Is this change an opportunity?’

The change may be in an unexpected success or an unexpected failure.

It may be in demographics.

It may, like the change on which Daiei has based so much of its growth, be in fundamental changes in world economy, in information and in world politics.

It may be in technology — and this, too, is an area which Daiei has used as an opportunity for successful innovation.

What is important is that this search for opportunity is done systematically, and permeates the entire organization, which also means that it has to be built into the personnel policy of the organization and its incentives, encouragement, and rewards.

Concept of mission

This is, of course, nothing but the merest sketch of a very big subject, but it should suffice to show that we know how to maintain the vitality of a business.

It does not lie in reacting to change.

It lies in renewing oneself continuously, by using change as an opportunity.

But this will work only, I repeat, if

the enterprise is also

managed for continuity,

and has at its foundation

a clear concept

of its mission and of its purpose

in society and economy.

January 12, 1995

Change and Continuity

in Management Challenges for the 21st Century

Basic Predictable Trends

in Managing in the Next Society

The center of modern society is

the managed institution —

Drucker style

Purpose and Objectives First

Not products or services (see marketing)

To Drucker, strategy, like everything else in management, is a thinking person’s game.

It isn’t arrived at by following some rigid set of rules but by thinking through various aspects of the business.

It all starts with objectives

How to guarantee non-performance How to guarantee non-performance

Management by Objectives — a user's guide Management by Objectives — a user's guide

“Only a clear definition of the mission makes possible clear and realistic business objectives.

It is the foundation for priorities, strategies, plans and work assignments.

It is the starting point for the design of managerial jobs, and, above all, for the design of managerial structures.

Structure follows strategy.

Strategy determines what the key activities are in a given business.

And strategy requires knowing what our business is and what it should be.

Chapters on “What is a Business” and “Business Purpose and Business Mission” in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices and Chapters 8 and 9 in Management, Revised Edition

Drucker also explained that “nothing may seem simpler or more obvious than to answer what a company’s business is.

A steel mill makes steel, a railroad runs to carry freight and passengers … .

Actually ‘what is our business?’ is almost always a difficult question which can be answered only after hard thinking and studying.

And the right answer is usually anything but obvious.”

Thinking back to Drucker’s Law, no strategy can be created without the customer, for it is the customer who defines business purpose.

And “therefore the question ‘what is our business?’ can be answered only by looking at the business from the outside, from the point of view of the customer and the market.

What the customer sees, thinks, believes and wants at any given time must be accepted by management as an objective fact deserving to be taken as seriously” as any hard data collected from salespeople, accountants, or engineers, contended Drucker.

Drucker claimed that the single most important cause of business failure can be attributed to management’s failure to ask the question “what is our business?” in a “clear and sharp form.”

And it isn’t only when a company is starting out that the question should be asked, or when the company is in trouble.

“On the contrary,” Drucker wrote, “to raise the question and to study it thoroughly is most needed when a business is successful.

For then failure to raise it may result in rapid decline.”

— Inside Drucker's Brain

Master mission page

A product or service name is never an effective answer to these questions because it doesn’t specify the specific contribution to the customer that matches what customers value and pay for — they buy what it does for them. See “The Customer: Joined at the Hip” in The Definitive Drucker and “Changing Values and Characteristics (creating a customer)” in Innovation and Entrepreneurship — bobembry

“Isao Nakauchi served in the Philippines as an infantryman during World War II. His business empire started in Osaka 1957 and it led to the creation of “American-style” supermarkets in Japan. In 1972 he led the biggest retailer in Japan, one that owned a store in Hawaii and a baseball team. The 1980s proved more difficult for the business as its competition and debts increased. He stepped down in 2002 and in 2004 he sold his stocks in the company. In 2005 he died of a stroke according to The University of Marketing and Distribution Sciences in Kobe, which he had founded.” — Wikipedia

What are you depending on?

“The stepladder is gone, and

there’s not even the implied structure

of an industry’s rope ladder.

It’s more like vines …

and you bring your own machete.

You don’t know what you’ll be doing next”

— Managing in a Time of Great Change

You can’t design your life

around a temporary organization — Peter Drucker

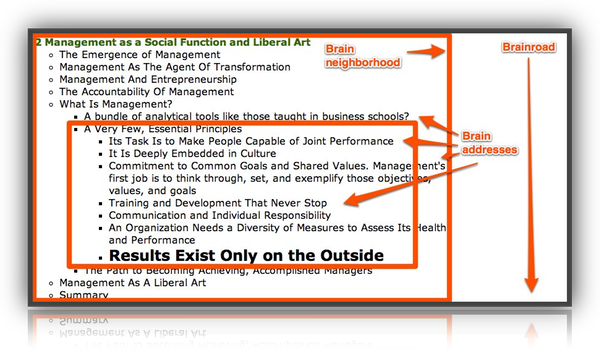

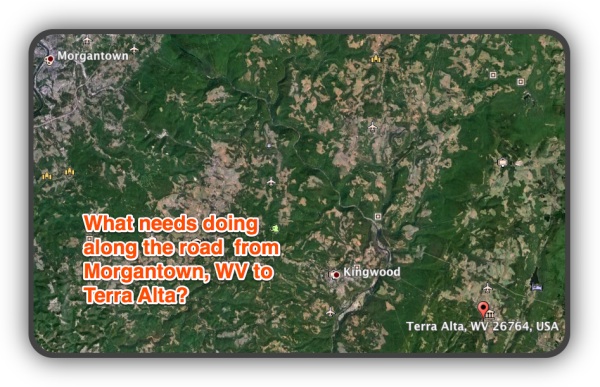

Thinking about brain travel and guidance:

“My brain has been down that road.”

Along the way I passed through various

brain neighborhoods and brain addresses.

I tried to pay attention.

When I wish, I can return, if I have a way of remembering.

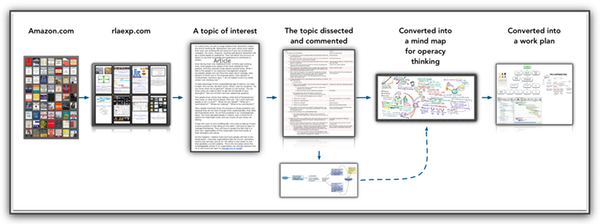

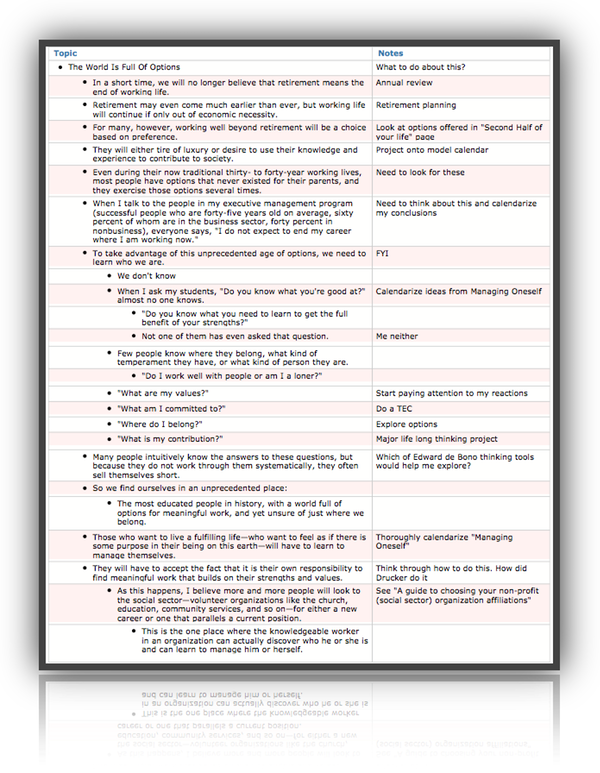

Just reading is not enough

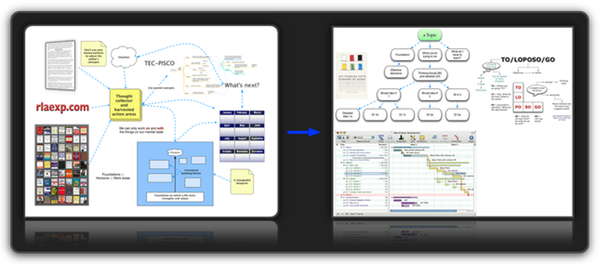

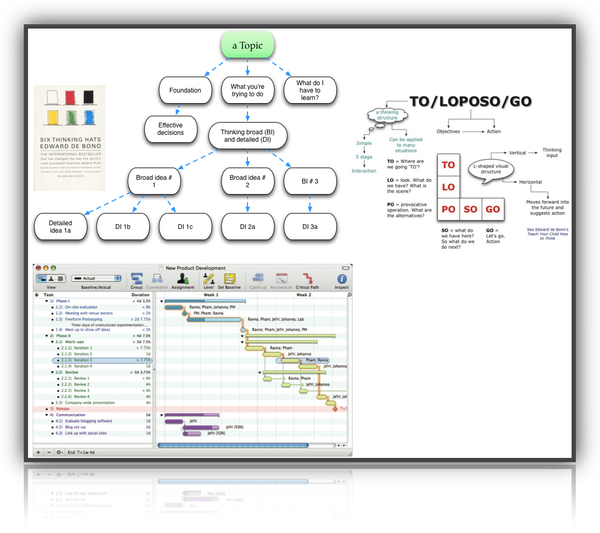

Calendarization: From awareness to action

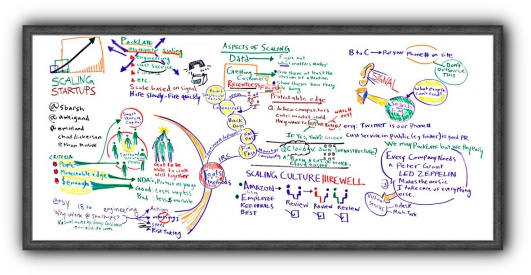

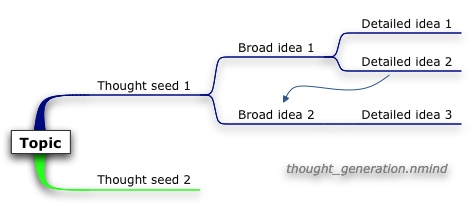

Dense reading and Dense listening and Thinking broad and Thinking detailed

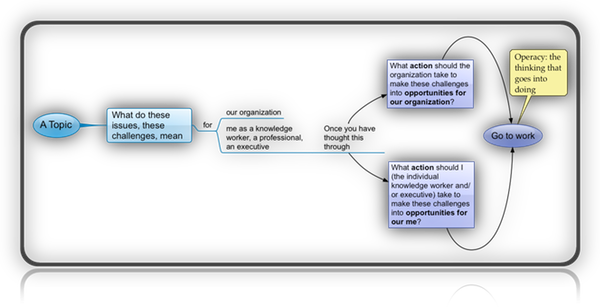

Larger view of image below

An action analysis on every sentence.

What are the implications of a particular sentence?

Dense reading and Dense Listening

Thinking broad and Thinking detailed

note the reflection ↑ and fog ↓

Challenge thinking and an alternative — operacy

Larger view

Note the fog and reflection ↓

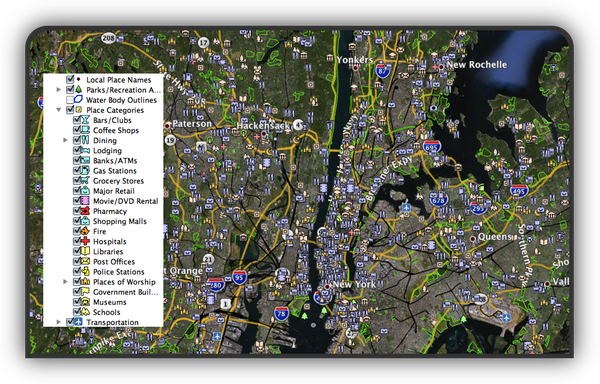

Questions ::: Thinking canvases

What needs doing around here?

A local view from Google Earth

|

![]()

![]()