Spending :: A foundation for FUTURE directed decisions

This page is about budgeting

as a management tool.

Every decision (and non-decision) has spending implications — time and money.

Most discussions of decision-making assume that only senior executives make decisions or that only senior executives decisions matter. This is a dangerous mistake. — Peter Drucker

This page covers a broad landscape and timescape

Everything takes place within

the “Sweep of History”

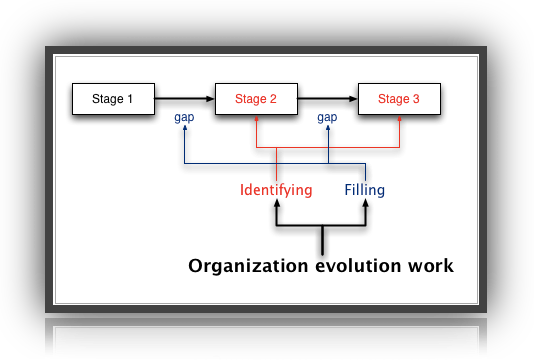

Organization evolution

Conditions of survival

Meet Peter Drucker

“The small- or medium-sized business usually cannot afford much

by way of top management. But if it wants to grow,

it better make sure that well ahead of time

it develops the top management it will need when it has grown” — PFD

Chapter 32: The Manager and the Budget in Management, Revised Edition

The Budget Is A Managerial Tool The Budget Is A Managerial Tool

Zero-Based Budgeting Zero-Based Budgeting

Types Of Cost Types Of Cost

Life-Cycle Budgeting Life-Cycle Budgeting

Operating Budget And Opportunities Budget (dual time dimensions) Operating Budget And Opportunities Budget (dual time dimensions)

Budgeting Human Resources Budgeting Human Resources

Budgeting And Control (see chapter 31) Budgeting And Control (see chapter 31)

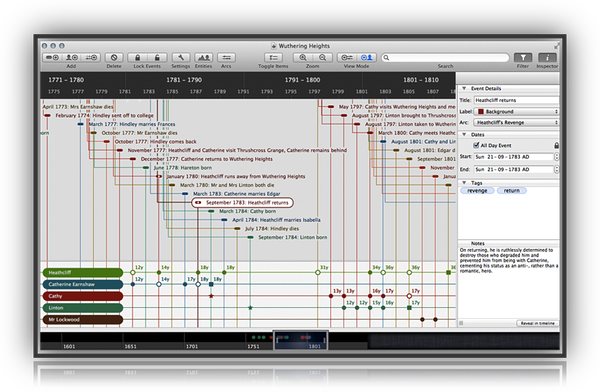

The Gantt Chart And Network Diagrams The Gantt Chart And Network Diagrams

Scrivener and Aeon Timeline

Judging Performance By Using The Budget Judging Performance By Using The Budget

Summary Summary

The ideas in this chapter are subordinate to the contents of chapters 8 through 11 for businesses

Amazon Links: Management Rev Ed and Management Cases, Revised Edition and Management Cases, Revised Edition

See contents of Management Cases, Revised Edition

Misallocation of resources

The 90/10 Rule at Yum! Brands

But every analysis of actual allocation of resources and efforts in business that I have ever seen or made showed clearly that the bulk of time, work, attention, and money first goes to ‘problems’ rather than to opportunities, and, secondly, to areas where even extraordinarily successful performance will have minimal impact on results. (calendarize this?)

One of the hardest things for a manager to remember is that of the 1,000 different situations he or she will be asked to deal with on any given day, only the smallest handful have a shot at moving the enterprise forward in a truly significant way (calendarize this?)

The job of management, then, is to make sure that financial capital, technology, and top talent are deployed where most of the results are and where most of the costs aren’t. The temptation often exists, however, to do exactly the opposite

See chapter 10, The Bright Idea (the riskiest and least successful source of innovative opportunities) in Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Broken Washroom Doors: Drucker said the problem of having people in positions where they do the least amount of good exists everywhere, but it is more rampant in hospitals, churches, and other nonprofits than in corporations.

To raise productivity in most any organization managers should regularly assess their key people, their strengths, and the results they achieve.

Then they should ask themselves:

Do we have the right people in the right jobs, where they can make the greatest contributions?

Are the jobs the right ones, meaning do we have people performing tasks that even if achieved do not add value to the organization?

What changes in people, jobs, and job functions can we make that will yield greater results?

Inside Drucker's Brain

Analysis of the entire business and its basic economics always shows it to be in worse disrepair than anyone expected.

The products everyone boasts of turn out to be yesterday's breadwinners or investments in managerial ego.

Activities to which no one paid much attention turn out to be major cost centers and so expensive as to endanger the competitive position of the company.

What everyone in the business believes to be quality turns out to have little meaning to the customer.

Important and valuable knowledge either is not applied where it could produce results or produces results no one uses.

I know more than one executive who fervently wished at the end of the analysis that he could forget all he had learned and go back to the old days of the “rat race” when “sufficient unto the day was the crisis thereof.”

But precisely because there are so many different areas of importance, the day-by-day method of management is inadequate even in the smallest and simplest business.

Because deterioration is what happens normally—that is, unless somebody counteracts it—there is need for a systematic and purposeful program.

There is need to reduce the almost limitless possible tasks to a manageable number.

There is need to concentrate scarce resources on the greatest opportunities and results.

There is need to do the few right things and do them with excellence.

Managing for Results

by Peter Drucker

Realities

Opportunities

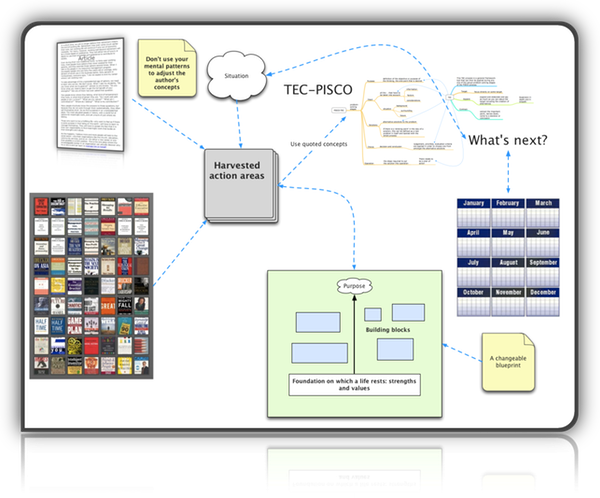

Exploring brainroads is preparation in a changing world

We can only work on and with the things on our mental radar

We can only navigate to the places on our radar

Larger

Drucker on profits and profitability

From The Frontiers of Management

... snip, snip ...

… These days I am always being asked to explain the success of the Japanese, especially as compared with the apparent malperformance of American business in recent years.

One reason for the difference is not, as is widely believed, that the Japanese are not profit conscious or that Japanese businesses operate at a lower profit margin.

This is pure myth.

In fact, when measured against the cost of capital — the only valid measurement for the adequacy of a company's profit—large Japanese companies have, as a rule, earned more in the last ten or fifteen years than comparable American companies.

And that is the main reason the Japanese have had the funds to invest in global distribution of their products.

Also, in sharp contrast to governmental behavior in the West, Japan's government, especially the powerful Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), is constantly pushing for higher industrial profits to ensure an adequate supply of funds for investment in the future—in jobs, in research, in new products, and in market development.

One of the principal reasons for the success of Japanese business is that Japanese managers do not start out with a desired profit, that is, with a financial objective in mind.

Rather, they start out with business objectives and especially with market objectives.

They begin by asking “How much market standing (not the same as market share) do we need to have leadership?”

“What new products do we need for this?”

“How much do we need to spend to train and develop people, to build distribution, to provide the required service?”

Only then do they ask “And how much profit is necessary to accomplish these business objectives?”

Then the resulting profit requirement is usually a good deal higher than the profit goal of the Westerner.

Second, Japanese businesses—perhaps as a long-term result of my management seminars twenty and thirty years ago—have come to accept what they originally thought was very strange doctrine.

They have come to accept my position that the end of business is not “to make money.”

Making money is a necessity of survival.

It is also a result of performance and a measurement thereof.

But in itself it is not performance.

As I mentioned earlier, the purpose of a business is to create a customer and to satisfy a customer. (being outside-in rather than inside-out)

That is performance and that is what a business is being paid for.

The job and function of management as the leader, decision maker, and value setter of the organization, and, indeed, the purpose and rationale of an organization altogether, is to make human beings productive so that the skills, expectations, and beliefs of the individual lead to achievement in joint performance.

These were the things which, almost thirty years ago, Ed Deming, Joe Juran, and I tried to teach the Japanese.

Even then, every American management text preached them.

The Japanese, however, have been practicing them ever since.

I have never slighted techniques in my teaching, writing, and consulting.

Techniques are tools; without tools, there is no “practice,” only preaching.

In fact, I have designed, or at least formulated, a good many of today’s management tools, such as management by objectives, decentralization as a principle of organizational structure, and the whole concept of “business strategy,” including the classification of products and markets.

My seminars in Japan also dealt heavily with tools and techniques.

In the summer of 1985, during my most recent trip to Japan, one of the surviving members of the early seminars reminded me that the first week of the very first seminar I ran opened with a question by a Japanese participant, “What are the most useful techniques of analysis we can learn from the West?”

We then spent several days of intensive work on breakeven analysis and cash-flow analysis: two techniques that had been developed in the West in the years immediately before and after World War II, and that were still unknown in Japan.

Similarly, I have always emphasized in my writing, in my teaching, and in my consulting the importance of financial measurements and financial results.

Indeed, most businesses do not earn enough.

What they consider profits are, in effect, true costs.

One of my central theses for almost forty years has been that one cannot even speak of a profit unless one has earned the true cost of capital.

And, in most cases, the cost of capital is far higher than what businesses, especially American businesses, tend to consider as “record profits.”

I have also always maintained—often to the scandal of liberal readers—that the first social responsibility of a business is to produce an adequate surplus.

Without a surplus, it steals from the commonwealth and deprives society and the economy of the capital needed to provide jobs for tomorrow.

Further, for more years than I care to remember, I have maintained that there is no virtue in being nonprofit and that, indeed, any activity that could produce a profit and does not do so is antisocial.

Professional schools are my favorite example.

There was a time when such activities were so marginal that their being subsidized by society could be justified.

Today, they constitute such a large sector that they have to contribute to the capital formation of an economy in which capital to finance tomorrow’s jobs may well be the central economic requirement, and even a survival need.

But central to my writing, my teaching, and my consulting has been the thesis that the modern business enterprise is a human and a social organization.

Management as a discipline and as a practice deals with human and social values.

To be sure, the organization exists for an end beyond itself.

In the case of the business enterprise, the end is economic (whatever this term might mean); in the case of the hospital, it is the care of the patient and his or her recovery; in the case of the university, it is teaching, learning, and research.

To achieve these ends, the peculiar modern invention we call management organizes human beings for joint performance and creates a social organization.

But only when management succeeds in making the human resources of the organization productive is it able to attain the desired outside objectives and results.

... snip, snip ... (calendarize this?)

For more Drucker's insights on profits and profitability: find the word stem "profit" here and click the indicated link.

An Operational View of the Budgeting Process

… The final conclusion is that we need a new approach to the process in which we make our value decisions between different objective areas—the budgeting process.

And in particular do we need a real understanding of that part of the budget that deals with the expenses that express these decisions, that is, the "managed" and "capital" expenditures.

Commonly today, budgeting is conceived as a financial process.

But it is only the notation that is financial; the decisions are entrepreneurial.

Commonly today, managed expenditures and capital expenditures are considered quite separate.

But the distinction is an accounting (and tax) fiction and misleading; both commit scarce resources to an uncertain future; both are, economically speaking, capital expenditures.

And they, too, have to express the same basic decisions on survival objectives to be viable.

Finally, today, most of our attention in the operating budget is given, as a rule, to other than the managed expenses, especially to the variable expenses, for that is where, historically, most money was spent.

But, no matter how large or small the sums, it is in our decisions on the managed expenses that we decide on the future of the enterprise.

Indeed, we have little control over what the accountant calls variable expenses—the expenses which relate directly to units of production and are fixed by a certain way of doing things.

We can change them, but not fast.

We can change a relationship between units of production and labor costs (which we, with a certain irony, still consider variable expenses despite the fringe benefits).

But within any time period these expenses can only be kept at a norm and cannot be changed.

This is, of course, even more true for the expenses in respect to the decisions of the past, our fixed expenses.

We cannot make them undone at all, whether these are capital expenses or taxes or what have you.

They are beyond our control.

In the middle, however, are the expenses for the future which express our risk-taking value choices: the capital expenses and the managed expenses.

Here are the expenses on facilities and equipment, on research and merchandising, on product development and people development, on management and organization.

This managed expense budget is the area in which we really make our decisions on our objectives.

(That, incidentally, is why I dislike accounting ratios in that area so very much, because they try to substitute the history of the dead past for the making of the prosperous future.)

We make decisions in this process in two respects.

First, what do we allocate people for?

For the money in the budget is really people.

What do we allocate people, and energy, and efforts to?

To what objectives?

We have to make choices, as we cannot do everything.

And, second, what is the time scale?

How do we, in other words, balance expenditures for long-term permanent efforts against any decision with immediate impact?

The one shows results only in the remote future, if at all.

The development of people (a fifteen-year job), the effectiveness of which is untested and unmeasurable, is, for instance, a decision on faith over the long range.

The other may show results immediately.

To slight the one, however, might, in the long range, debilitate the business and weaken it.

And, yet, there are certain real short-term needs that have to be met in the business—in the present as well as in the future.

Until we develop a clear understanding of basic survival objectives and some yardsticks for the decisions and choices in each area, budgeting will not become a rational exercise of responsible judgment; it will retain some of the hunch character that it now has.

But our experience has shown that the concept of survival objectives alone can greatly improve both the quality and effectiveness of the process and the understanding of what is being decided.

Indeed, it gives us, we are learning, an effective tool for the integration of functional work and specialized efforts and especially for creating a common understanding throughout the organization and common measurements of contribution and performance.

The approach to a discipline of business enterprise through an analysis of survival objectives is still a very new and a very crude one.

Yet it is already proving itself a unifying concept, simply because it is the first general theory of the business enterprise we have had so far.

It is not yet a very refined, a very elegant, let alone a very precise, theory.

Any physicist or mathematician would say: This is not a theory; this is still only rhetoric.

But at least, while maybe only in rhetoric, we are talking about something real.

For the first time we are no longer in the situation in which theory is irrelevant, if not an impediment, and in which practice has to be untheoretical, which means cannot be taught, cannot be learned, and cannot be conveyed, as one can only convey the general.

This should thus be one of the breakthrough areas; and twenty years hence this might well have become the central concept around which we can organize the mixture of knowledge, ignorance, and experience, of prejudices, insights, and skills, which we call "management" today.

Technology, Management and Society (1970)

The development of people

Needs to be a Drucker inspired agenda based on his understanding of the world and not a self-serving HR agenda. Framework thinking is needed starting with organization objectives. Management’s task is to make people capable of joint performance, to make their strengths effective and their weaknesses irrelevant.

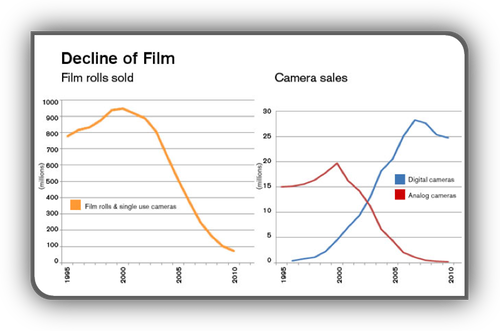

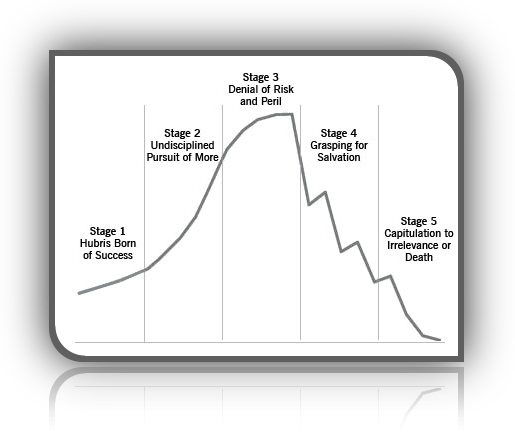

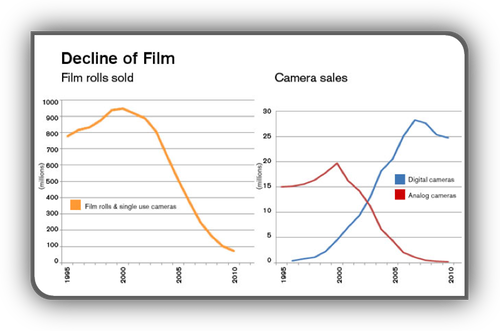

The Shakeout (calendarize this?)

The “shakeout” sets in as soon as the “window” closes.

And the majority of ventures started during the “window” period do not survive the shakeout, as has already been shown for such high-tech industries of yesterday as railroads, electrical apparatus makers, and automobiles.

As these lines are being written, the shakeout has begun among microprocessor, minicomputer, and personal computer companies—only five or six years after the “window” opened.

Today, there are perhaps a hundred companies in the industry in the United States alone.

Ten years hence, by 1995, there are unlikely to be more than a dozen left of any size or significance.

But which ones will survive, which ones will die, and which ones will become permanently crippled—able neither to live nor to die—is unpredictable.

In fact, it is futile to speculate.

Sheer size may ensure survival.

But it does not guarantee success in the shakeout, otherwise Allied Chemical rather than DuPont would today be the world’s biggest and most successful chemical company.

In 1920, when the “window” opened for the chemical industry in the United States, Allied Chemical looked invincible, if only because it had obtained the German chemical patents which the U.S. government had confiscated during World War I.

Seven years later, after the shakeout, Allied Chemical had become a weak also-ran.

It has never been able to regain momentum.

No one in 1949 could have predicted that IBM would emerge as the computer giant, let alone that such big, experienced leaders as G.E. or Siemens would fail completely.

No one in 1910 or 1914 when automobile stocks were the favorites of the New York Stock Exchange could have predicted that General Motors and Ford would survive and prosper and that such universal favorites as Packard or Hupmobile would disappear.

No one in the 1870s and 1880s, the period in which the modern banks were born, could have predicted that Deutsche Bank would swallow up dozens of the old commercial banks of Germany and emerge as the leading bank of the country.

That a certain industry will become important is fairly easy to predict.

There is no case on record where an industry that reached the explosive phase, the “window” phase, as I called it, has then failed to become a major industry.

The question is, Which of the specific units in this industry will be its leaders and so survive?

This rhythm—a period of great excitement during which there is also great speculative ferment, followed by a severe “shakeout”—is particularly pronounced in the high-tech industries.

In the first place, such industries are in the limelight and thus attract far more entrants and far more capital than more mundane areas.

Comments by Warren Buffett.

Also the expectations are much greater.

More people have probably become rich building such prosaic businesses as a shoe-polish or a watchmaking company than have become rich through high-tech businesses.

Yet no one expects shoe-polish makers to build a “billion-dollar business,” nor considers them a failure if all they build is a sound but modest family company.

(Managing the Family Business: see December 28 and 29 in The Daily Drucker)

High tech, by contrast, is a “high-low game,” in which a middle hand is considered worthless.

And this makes high-tech innovation inherently risky.

But also, high tech is not profitable for a very long time.

The world’s computer industry began in 1947-48.

Not until the early 1980s, more than thirty years later, did the industry as a whole reach break-even point.

To be sure, a few companies (practically all of them American, by the way) began to make money much earlier.

And one, IBM, the leader, began to make a great deal of money earlier still.

But across the industry the profits of those few successful computer makers were more than offset by the horrendous losses of the rest; the enormous losses, for instance, which the big international electrical companies took in their abortive attempts to become computer manufacturers.

And exactly the same thing happened in every earlier “high-tech” boom—in the railroad booms of the early nineteenth century, in the electrical apparatus and the automobile booms between 1880 and 1914, in the electric appliance and the radio booms of the 1920s, and so on.

One major reason for this is the need to plow more and more money back into research, technical development, and technical services to stay in the race.

High tech does indeed have to run faster and faster in order to stand still.

This is, of course, part of its fascination.

But it also means that when the shakeout comes, very few businesses in the industry have the financial resources to outlast even a short storm.

This is the reason why high-tech ventures need financial foresight even more than other new ventures, but also the reason why financial foresight is even scarcer among high-tech new ventures than it is among new ventures in general.

(Find “financial foresight” in Innovation and Entrepreneurship and see chapter 3 in The Changing World of the Executive)

There is only one prescription for survival during the shakeout: entrepreneurial management (described in Chapters 12-15).

What distinguished Deutsche Bank from the other “hot” financial institutions of its time was that Georg Siemens thought through and built the world’s first top management team.

What distinguished DuPont from Allied Chemical was that DuPont in the early twenties created the world’s first systematic organization structure, the world’s first long-range planning, and the world’s first system of management information and control.

Allied Chemical, by contrast, was run arbitrarily by one brilliant egomaniac.

But this is not the whole story.

Most of the large companies that failed to survive the more recent computer shakeout — G.E. and Siemens, for instance—are usually considered to have first-rate management.

And the Ford Motor Company survived, though only by the skin of its teeth, even though it was grotesquely mismanaged during the shakeout years.

Entrepreneurial management is thus probably a precondition of survival, but not a guarantee thereof.

And at the time of the shakeout, only insiders (and perhaps not even they) can really know whether a knowledge-based innovator that has grown rapidly for a few boom years is well managed, as DuPont was, or basically unmanaged, as Allied Chemical was.

By the time we do know, it is likely to be too late.

Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Related

Chapters from The Changing World of The Executive Chapters from The Changing World of The Executive

Helping Small Business Cope Helping Small Business Cope

Inflation-Proofing the Company Inflation-Proofing the Company

A Scorecard for Managers A Scorecard for Managers

Managing Capital Productivity Managing Capital Productivity

Measuring Business Performance Measuring Business Performance

Good Growth and Bad Growth Good Growth and Bad Growth

What do you want to be remembered for? What do you want to be remembered for?

What Executives Should Remember What Executives Should Remember

The Theory of the Business The Theory of the Business

Managing for Business Effectiveness Managing for Business Effectiveness

What Businesses Can Learn from Nonprofits What Businesses Can Learn from Nonprofits

The New Society of Organizations The New Society of Organizations

The Information Executives Truly Need The Information Executives Truly Need

Managing Oneself Managing Oneself

They're Not Employees, They're People They're Not Employees, They're People

What Makes an Executive Effective What Makes an Executive Effective

Other specific chapters in Management, Revised Edition Other specific chapters in Management, Revised Edition

8 The Theory of the Business 8 The Theory of the Business

9 The Purpose and Objectives of a Business 9 The Purpose and Objectives of a Business

10 Making the Future Today 10 Making the Future Today

11 Strategic Planning 11 Strategic Planning

31 Controls, Control, and Management 31 Controls, Control, and Management

33 Information Tools and Concepts 33 Information Tools and Concepts

Part III Performance in Service Institutions Part III Performance in Service Institutions

Part IV: Productive Work and Achieving Worker Part IV: Productive Work and Achieving Worker

The New Productivity Challenge

But now the planning people—still about the same number—work through only three questions for each of the company’s businesses:

What market standing does it need to maintain leadership?

What innovative performance does it need to support the needed market standing?

What rate of return is the minimum needed to earn the cost of capital?

And then the planning people together with the operating executives in each business work out broad strategy guidelines to attain these goals under different assumptions regarding economic conditions … But they have become the “flight plans” that guide the company’s businesses and its senior executives.

Part I Management's New Realities Part I Management's New Realities

Part VIII Innovation and Entrepreneurship Part VIII Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

Managing for Results or "Managing for Business Effectiveness" in Peter Drucker on the Profession of Management AND/OR “From Analysis to Perception—The New Worldview” Managing for Results or "Managing for Business Effectiveness" in Peter Drucker on the Profession of Management AND/OR “From Analysis to Perception—The New Worldview”

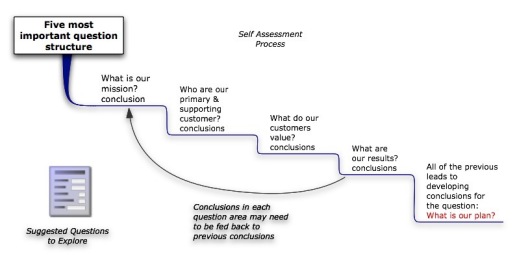

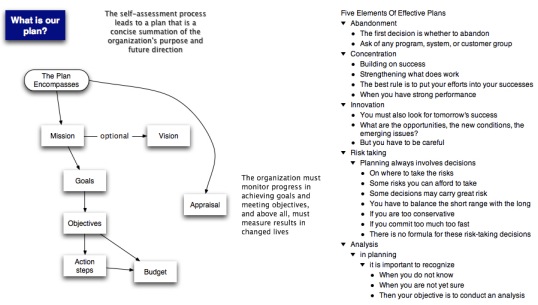

The Five Most Important Questions You Will Ever Ask About Your Organization The Five Most Important Questions You Will Ever Ask About Your Organization

Innovation and Entrepreneurship specifically The Practice of Entrepreneurship and chapters 3 - 10 Innovation and Entrepreneurship specifically The Practice of Entrepreneurship and chapters 3 - 10

Management Challenges for the 21st Century Management Challenges for the 21st Century

The Definitive Drucker The Definitive Drucker

Competing for the Future Competing for the Future

Chaotics Chaotics

Management Alert Management Alert

Management Golf Management Golf

Trigger Points Trigger Points

Reality Check Reality Check

Toyota Production System Toyota Production System

Drucker of Asia Drucker of Asia

PIMS PIMS

Life-TIME Investment System Life-TIME Investment System

Links to other topics can be found on my site map

Thinking broad and thinking detailed Thinking broad and thinking detailed

Turnaround menu Turnaround menu

People decisions the real control of an organization People decisions the real control of an organization

Find “cost” in The Daily Drucker Find “cost” in The Daily Drucker

Marketing Marketing

Abandonment Abandonment

Innovation Innovation

There is a cost structure here that needs to be mind mapped.

Managing in the Next Society Managing in the Next Society

Management Challenges for the 21st Century and Managing in the Next Society Management Challenges for the 21st Century and Managing in the Next Society

Information challenges

The change leader

Knowledge ::: society of organizations ::: management Knowledge ::: society of organizations ::: management

Management by Objectives — a user's guide

CEO work area landscapes may provide ideas you want to exploit. CEO work area landscapes may provide ideas you want to exploit.

High tech is living in the nineteenth century, the pre-management world. They believe that people pay for technology. They have a romance with technology. But people don't pay for technology: they pay for what they get out of technology. The Frontiers of Management

Management's new paradigms (calendarize this?)

AS WE ADVANCE deeper into the knowledge economy, the basic assumptions underlying much of what is taught and practiced in the name of management are hopelessly out of date. (calendarize this?)

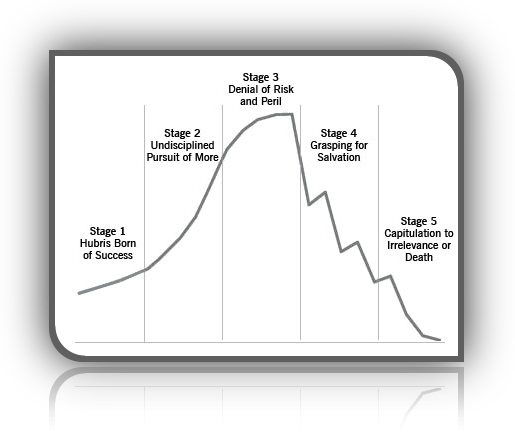

Financial results: positive financial results don't last that long … Don't relax when the numbers look good. Check out what happened to the In Search of Excellence companies. There is a complexity here that goes way beyond the intent of this page. Message: keep moving toward tomorrowS … Beware of the research methodology used to promote somebody’s “answer.” Yesterday's top performing organizations rest on different realities … See the five deadly sins, the shakeout, and Drucker on profitability below. There is a need to think in terms of real world “economics” not the world according to accountants and tax collectors. There is much mumbo-jumbo here and lots of people trying to make a monkey out of those who are naive.

Decisions, decisions, decisions: where everything comes together

Keywords: tlnkwbudgeting tlnkwspending

|

![]()

![]()