Argument versus Parallel Thinking

The basic idea behind Western thinking was designed about twenty-three hundred years ago by the Greek “Gang of Three” and is based on argument.

Socrates put a high emphasis on dialectic and argument.

In 80 percent of the dialogues in which he was involved (as written up by Plato) there is no constructive outcome at all.

Socrates saw his role as simply pointing out what was “wrong.”

He wanted to clarify the correct use of concepts like justice and love by pointing out incorrect usage.

Plato believed that the “ultimate” truth was hidden below appearances.

His famous analogy is of a person chained up in a cave so that he can see only the back wall of the cave.

There is a fire at the entrance to the cave.

After a person enters the cave, his shadow is projected onto the back wall of the cave and that is all the chained-up person can see.

Plato used this analogy to point out that as we go through life we can see only the “shadows” of the truth.

Aristotle systematized inclusion/exclusion logic.

From past experience we would put together “boxes,” definitions, categories or principles.

When we came across something, we judged into which box it fell.

Something could be in the box or not in the box.

It could not be half in and half out nor could it be anywhere else.

As a result, Western thinking is concerned with “what is,” which is determined by analysis, judgement and argument.

That is a fine and useful system.

But there is another whole aspect of thinking that is concerned with “what can be,” which involves constructive thinking, creative thinking, and “designing a way forward.”

In 1998, I was asked to give an opening talk at the Australian Constitutional Convention that was looking at the future of federation.

I told the following story.

Once upon a time a man painted half his car white and the other half black.

His friends asked him why he did such a strange thing.

He replied: “Because it is such fun, whenever I have an accident, to hear the witnesses in court contradict each other.”

At the end of the convention the chairperson, Sir Anthony Mason, told me that he was going to use that story because it is so often the case in an argument that both sides are right but are looking at different aspects of the situation.

Many cultures in the world, perhaps even the majority of cultures, regard argument as aggressive, personal and non-constructive.

That is why so many cultures readily take up the parallel thinking of the Six Hats method.

See What is Parallel Thinking? further down the page

A Changing World

A thinking system based on argument is excellent just as the front left wheel of a car is excellent.

There is nothing wrong with it at all.

But it is not sufficient.

A doctor is treating a child with a rash.

The doctor immediately thinks of some possible “boxes.”

Is it sunburn?

Is it food allergy?

Is it measles?

The doctor then examines the signs and symptoms and makes a judgement.

If the doctor judges that the condition fits into the “measles” box, then the treatment of measles is written on the side of that “box” and the doctor knows exactly what to do.

That is traditional thinking at its best.

From the past we create standard situations.

We judge into which “standard situation box” a new situation falls.

Once we have made this judgement, our course of action is clear.

Such a system works very well in a stable world.

In a stable world the standard situations of the past still apply.

But in a changing world the standard situations may no longer apply.

Instead of judging our way forward, we need to design our way forward.

We need to be thinking about “what can be,” not just about “what is.”

Yet the basic tradition of Western thinking (or any other thinking) has not provided a simple model of constructive thinking.

That is precisely what the Six Hats method (parallel thinking) is all about.

What Is Parallel Thinking?

There is a large and beautiful country house.

One person is standing in front of the house.

One person is standing behind the house.

Two other people are standing on each side of the house.

All four have a different view of the house.

All four are arguing (by intercom) that the view each is seeing is the correct view of the house.

Using parallel thinking they all walk around and look at the front.

Then they all walk around to the side, then the back, and finally the remaining side.

So at each moment each person is looking in parallel from the same point of view.

This is almost the exact opposite of argument, adversarial, confrontational thinking where each party deliberately takes an opposite view.

Because each person eventually looks at all sides of the building, the subject is explored fully.

Parallel thinking means that at any moment everyone is looking in the same direction.

But parallel thinking goes even further.

In traditional thinking, if two people disagree, there is an argument in which each tries to prove the other party wrong.

In parallel thinking, both views, no matter how contradictory, are put down in parallel.

If, later on, it is essential to choose between the differing positions, then an attempt to choose is made at that point.

If a choice cannot be made, then the design has to cover both possibilities.

At all times the emphasis is on designing a way forward.

Directions and Hats

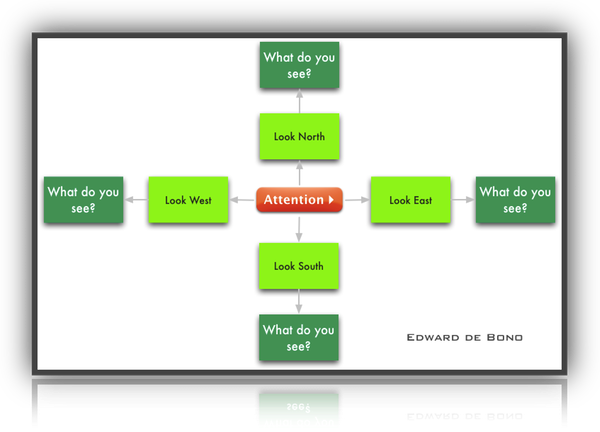

The essence of parallel thinking is that at any moment everyone is looking in the same direction—but the direction can be changed.

An explorer might be asked to look north or to look east.

Those are standard direction labels.

So we need some direction labels for thinking.

What are the different directions in which thinkers can be invited to look?

This is where the hats come in.

In many cultures there is already a strong association between thinking and “thinking hats” or “thinking caps.”

The value of a hat as a symbol is that it indicates a role.

People are said to be wearing a certain hat.

Another advantage is that a hat can be put on or taken off with ease.

A hat is also visible to everyone around.

For those reasons I chose hats as the symbols for the directions of thinking.

Although physical hats are sometimes used, the hats are usually imaginary.

Posters of the hats on the walls of meeting rooms often are used, however, as a reminder of the directions.

There are six colored hats corresponding to the six directions of thinking: white, red, black, yellow, green, blue.

Note on Using the Thinking Hats

When people tell me that they have been using the Six Hats method, I often ask how they have been using it, and discover that sometimes they have been using it incorrectly.

In a meeting, someone has been chosen as the black hat thinker, someone else as the white hat thinker, and so on.

The people then keep those roles for the whole meeting.

That is almost exactly the opposite of how the system should be used.

The whole point of parallel thinking is that the experience and intelligence of everyone should be used in each direction.

So everyone present wears the black hat at the appointed time.

Everyone present wears the white hat at another time.

That is parallel thinking and makes fullest use of everyone’s intelligence and experience.

Showing Off

Many people tell me that they enjoy argument because they can show off how clever they are.

They can win arguments and demolish opponents.

None of that is very constructive but there may be a human need to show off.

Thus showing off is not excluded from parallel thinking and the Six Hats method.

A thinker now shows off by showing how many considerations he or she can put forward under the yellow hat, how many under the black hat, and so forth.

You show off by performing well as a thinker.

You show off by performing better as a thinker than others in the meeting.

The difference is that this type of showing off is constructive.

The ego is no longer tied to being right.

Time Saving

Optus (in Australia) had set aside four hours for an important discussion.

Using the Six Hats method the discussion was concluded in forty-five minutes.

From every side there are reports of how much quicker meetings become when the six hats are used.

Meetings take half the time.

Meetings take a third or a quarter of the time.

Sometimes, as in the case of ABB, meetings take one-tenth of the time.

In the United States, managers spend nearly 40 percent of their time in meetings.

If the Six Hats method reduced all meeting times by 75 percent, you would have created 30 percent more manager time—at no extra cost whatsoever.

In normal thinking or argument, if someone says something, then others have to respond—even if only out of politeness.

But that is not the case with parallel thinking.

With parallel thinking, every thinker at every moment is looking in the same direction.

The thoughts are laid out in parallel.

You do not respond to what the last person has said.

You simply add another idea in parallel.

In the end, the subject is fully explored quickly.

Normally, if two points of view are at odds, then they are argued out.

With parallel thinking, both points of view are laid out alongside each other.

Later on, if it is essential to decide between the two, a decision is made.

So there is not argument at every step.

The White Hat

Think of paper. Think of a computer printout. The white hat is about information. When the white hat is in use, everyone focuses directly and exclusively on information.

What information do we have?

What information do we need?

What information is missing?

What questions do we need to ask?

How are we going to get the information we need?

The information can range from hard facts and figures that can be checked to soft information like opinions and feelings.

If you express your own feeling, that is red hat, but if you report on someone else expressing a feeling, that is white hat.

When two offered pieces of information disagree, there is no argument on that point.

Both pieces of information are put down in parallel.

Only if it becomes essential to choose between them will the choice be made.

The white hat is usually used toward the beginning of a thinking session as a background for the thinking that is going to take place.

The white hat also can be used toward the end of the session as a sort of assessment: Do our proposals fit in with the existing information?

The white hat is neutral.

The white hat reports on the world.

The white hat is not for generating ideas though it is permissible to report on ideas that are in use or have been suggested.

A very important part of the white hat is to define the information that is missing and needed.

The white hat defines the questions that should be asked.

The white hat lays out the means (such as surveys and questionnaires) for obtaining the needed information.

White hat energy is directed at seeking out and laying out information.

Black Hat Thinking Content and Process

Point out errors in thinking.

Question the strength of the evidence.

Does the conclusion follow?

Is it the only possible conclusion?

A great deal of traditional Western argument attacks the process of the argument: if the process is incorrect, then the conclusion cannot be correct.

In fact, the conclusion can indeed be correct, but has not been proved to be correct.

Because the Six Hats method is so different from argument there is no need for detailed discussion of process.

Nevertheless, under the black hat it is possible to point out deficiencies in the thinking process itself.

That remark you made is an assumption, not a fact .

… Your conclusion does not follow from what you have been telling us .

… Those figures are not the ones you showed last time .

… That is only one possible explanation. But it is by no means the only one.

It would destroy the value of the whole method if a person were allowed to interrupt at any point with those sorts of comments.

We would be back to the limitations of the argument mode.

So the thinker should note and accumulate the main points of criticism and put them forward only when the black hat is in use.

Under the white hat someone puts forward a set of sales figures.

One person present knows that the figures are actually five years old.

Should that person interrupt and point out the error?

It would be better to lay out another white hat point.

The figures you have been given are five years old.

We do not have more up-to-date figures.

Because the Six Hats method is very different from argument, the rules of argument do not apply.

It is no longer a matter of arguing from one point to another but of filling the field with possibilities.

If we increase prison sentences and penalties, we will reduce crime.

That seems a logical enough deduction, but it may not be valid in practice.

If the risk of getting caught is actually very low, or is perceived to be very low, then the increase in punishment may have little effect.

It is also possible that crime could get more violent: a criminal may now be inclined to kill a victim to remove the witness.

Also, longer stays in prison might turn casual criminals into hardened criminals through the influence of the inmates.

These are all possibilities.

Far too often proof is no more than lack of imagination.

If there were actual white hat figures to show that increased penalties reduced crime in the long term as well as in the short term, then those figures would be more valuable than apparently logical deduction.

Holiday travel is likely to increase because family incomes are increasing, airfares are going down, travel is better organized and there may be fewer children.

It is possible that people will get bored with travel.

Technology might provide new ways of being entertained at home.

Diseases in far-off places might discourage travel.

Those possibilities are laid down alongside each other, as in parallel thinking.

Parallel thinking lays out different viewpoints and disagreements.

Logical deduction insists on certainty.

The Six Hats method deals with possibilities and likelihood.

In the real world it is very difficult to be certain.

Action has to be taken on “likelihood.”

That is indeed a possibility.

But you have not proved it as a certainty.

There are indeed times when matters can be dealt with in a cut-and-dried, logical fashion.

The bulk of practical thinking, however, is on the basis of likelihood.

Although it is very tempting, the black hat is not permission to go back to “argument.”

Procedural errors can be pointed out.

Parallel statements that express a differing point of view can be laid down.

In the end there should be a clear map of possible problems, obstacles, difficulties and dangers.

These can be clarified and elaborated.

Under the green hat an attempt is made to overcome or cope with the difficulties suggested under the black hat.

To begin with, people do find it hard not to jump in to disagree with a point that has just been made.

It is up to the chairperson or facilitator to maintain the hat discipline.

![]()