|

Knowledge :: Society of organizations :: Management

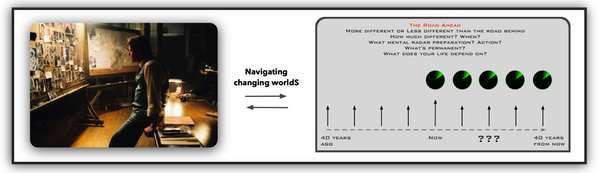

From Analysis to Perception — The New World View

The image title reads “The basic organization of today’s (crossed out) yesterday’s economy because its composition was created in the past. For any organ of the economy to grow to substantial size takes a long time and a “high” growth rate. The longer the time involved the greater the opportunity to be obsolescent or obsolete.

The flow presented in the illustration omits the reality of the production process: The Toyota Production System; pirate attacks at sea;

And then there’s Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything (P.S.) , where organizations reside, and those monitoring your Internet tracks. , where organizations reside, and those monitoring your Internet tracks.

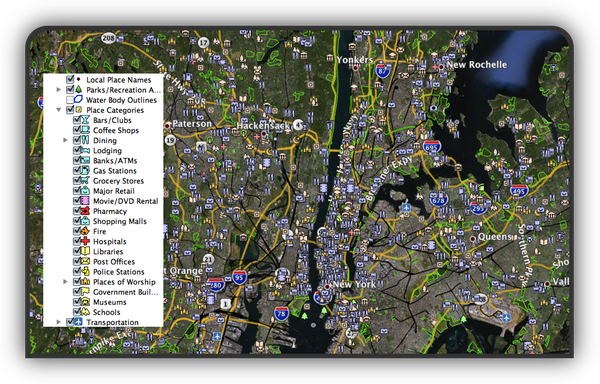

A local view from Google Earth

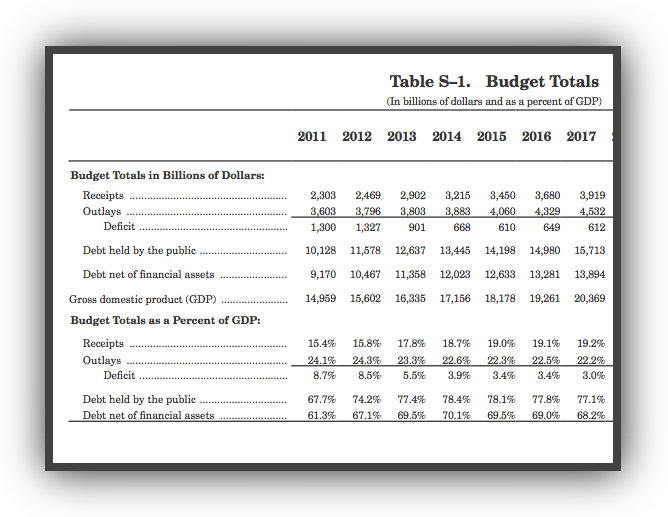

The Federal Budget

Links on the illustration above:

“Economists never know anything until twenty years later. There are no slower learners than economists. There is no greater obstacle to learning than to be the prisoner of totally invalid but dogmatic theories. The economists are where the theologians were in 1300: prematurely dogmatic” — Frontiers of Management

Management and Economic Development:

“Management creates economic and social development.

Economic and social development is the result of management.

It can be said, without too much oversimplification, that there are no “underdeveloped countries.”

There are only “undermanaged” ones.

This means that management is the prime mover and that development is a consequence.

All our experience in economic development proves this.

Wherever we have only capital, we have not achieved development.

In the few cases where we have been able to generate management energies, we have generated rapid development.

Development, in other words, is a matter of human energies rather than of economic wealth.

And the generation and direction of human energies is the task of management.”

Feb 20 — The Daily Drucker

Competition on the roads ahead

… In the new mental geography created by the railroad, humanity mastered distance. In the mental geography of e-commerce, distance has been eliminated. There is only one economy and only one market.

One consequence of this is that every business must become globally competitive, even if it manufactures or sells only within a local or regional market. The competition is not local anymore—in fact, it knows no boundaries. Every company has to become transnational in the way it is run. Yet the traditional multinational may well become obsolete. It manufactures and distributes in a number of distinct geographies, in which it is a local company. But in e-commerce there are neither local companies nor distinct geographies. Where to manufacture, where to sell, and how to sell will remain important business decisions. But in another twenty years they may no longer determine what a company does, how it does it, and where it does it.

At the same time, it is not yet clear what kinds of goods and services will be bought and sold through e-commerce and what kinds will turn out to be unsuitable for it. This has been true whenever a new distribution channel has arisen. Why, for instance, did the railroad change both the mental and the economic geography of the West, whereas the steamboat—with its equal impact on world trade and passenger traffic—did neither? Why was there no "steamboat boom"?

Equally unclear has been the impact of more recent changes in distribution channels—in the shift, for instance, from the local grocery store to the supermarket, from the individual supermarket to the supermarket chain, and from the supermarket chain to Wal-Mart and other discount chains. It is already clear that the shift to e-commerce will be just as eclectic and unexpected. …

Managing in the Next Society

by Peter Drucker

See Marketing Moves and Chaotics: The Business of Managing and Marketing in the Age of Turbulence

Changing Values and Characteristics

From chapter 19 of Innovation and Entrepreneurship by Peter Drucker

Amazon link: Innovation and Entrepreneurship

In the entrepreneurial strategies discussed so far, the aim is to introduce an innovation.

In the entrepreneurial strategy discussed in this chapter, the strategy itself is the innovation.

The product or service it carries may well have been around a long time—in our first example, the postal service, it was almost two thousand years old.

But the strategy converts this old, established product or service into something new.

It changes its utility, its value, its economic characteristics.

While physically there is no change, economically there is something different and new.

All the strategies to be discussed in this chapter have one thing in common.

They create a customer — and that is the ultimate purpose of a business, indeed, of economic activity.

As was first said more than thirty years ago in my The Practice of Management (New York: Harper & Row, 1954).

But they do so in four different ways:

by creating utility by creating utility

by pricing by pricing

by adaptation to the customer’s social and economic reality by adaptation to the customer’s social and economic reality

by delivering what represents true value to the customer by delivering what represents true value to the customer

... snip, snip ...

These examples are likely to be considered obvious.

Surely, anybody applying a little intelligence would have come up with these and similar strategies?

But the father of systematic economics, David Ricardo, is believed to have said once, “Profits are not made by differential cleverness, but by differential stupidity.”

The strategies work, not because they are clever, but because most suppliers—of goods as well as of services, businesses as well as public-service institutions—do not think.

They work precisely because they are so “obvious.”

Why, then, are they so rare?

For, as these examples show, anyone who asks the question, What does the customer really buy? will win the race.

In fact, it is not even a race since nobody else is running.

What explains this?

One reason is the economists and their concept of “value.”

Every economics book points out that customers do not buy a “product,” but what the product does for them.

And then, every economics book promptly drops consideration of everything except the “price” for the product, a “price” defined as what the customer pays to take possession or ownership of a thing or a service.

What the product does for the customer is never mentioned again.

Unfortunately, suppliers, whether of products or of services, tend to follow the economists.

It is meaningful to say that “product A costs X dollars.”

It is meaningful to say that “we have to get Y dollars for the product to cover our own costs of production and have enough left over to cover the cost of capital, and thereby to show an adequate profit.”

But it makes no sense at all to conclude and therefore the customer has to pay the lump sum of Y dollars in cash for each piece of product A he buys.”

Rather, the argument should go as follows: “What the customer pays for each piece of the product has to work out as Y dollars for us.

But how the customer pays depends on what makes the most sense to him.

It depends on what the product does for the customer.

It depends on what fits his reality.

It depends on what the customer sees as ‘value.’”

Price in itself is not “pricing,” and it is not “value.”

It was this insight that gave King Gillette a virtual monopoly on the shaving market for almost forty years; it also enabled the tiny Haloid Company to become the multibillion-dollar Xerox Company in ten years, and it gave General Electric world leadership in steam turbines.

In every single case, these companies became exceedingly profitable.

But they earned their profitability.

They were paid for giving their customers satisfaction, for giving their customers what the customers wanted to buy, in other words, for giving their customers their money’s worth.

“But this is nothing but elementary marketing,” most readers will protest, and they are right.

It is nothing but elementary marketing.

To start out with the customer’s utility, with what the customer buys, with what the realities of the customer are and what the customer’s values are—this is what marketing is all about.

But why, after forty years of preaching Marketing, teaching Marketing, professing Marketing, so few suppliers are willing to follow, I cannot explain.

The fact remains that so far, anyone who is willing to use marketing as the basis for strategy is likely to acquire leadership in an industry or a market fast and almost without risk.

Entrepreneurial strategies are as important as purposeful innovation and entrepreneurial management.

Together, the three make up innovation and entrepreneurship.

The available strategies are reasonably clear, and there are only a few of them.

But it is far less easy to be specific about entrepreneurial strategies than it is about purposeful innovation and entrepreneurial management.

We know what the areas are in which innovative opportunities are to be found and how they are to be analyzed.

There are correct policies and practices and wrong policies and practices to make an existing business or public-service institution capable of entrepreneurship; right things to do and wrong things to do in a new venture.

But the entrepreneurial strategy that fits a certain innovation is a high-risk decision.

Some entrepreneurial strategies are better fits in a given situation, for example, the strategy that I called entrepreneurial judo, which is the strategy of choice where the leading businesses in an industry persist year in and year out in the same habits of arrogance and false superiority.

We can describe the typical advantages and the typical limitations of certain entrepreneurial strategies.

Above all, we know that an entrepreneurial strategy has more chance of success the more it starts out with the users—their utilities, their values, their realities.

An innovation is a change in market or society.

It produces a greater yield for the user, greater wealth-producing capacity for society, higher value or greater satisfaction.

The test of an innovation is always what it does for the user.

Hence, entrepreneurship always needs to be market-focused, indeed, market-driven.

Still, entrepreneurial strategy remains the decision-making area of entrepreneurship and therefore the risk-taking one.

It is by no means hunch or gamble.

But it also is not precisely science.

Rather, it is judgment.

What do customers value?

The question, What do customers value?—what satisfies their needs, wants, and aspirations—is so complicated that it can only be answered by customers themselves.

And the first rule is that there are no irrational customers.

Almost without exception, customers behave rationally in terms of their own realities and their own situation. (Their logic bubble — see below)

Leadership should not even try to guess at the answers but should always go to the customers in a systematic quest for those answers.

I practice this.

Each year I personally telephone a random sample of fifty or sixty students who graduated ten years earlier.

I ask, “Looking back, what did we contribute in this school?

What is still important to you?

What should we do better?

What should we stop doing?”

And believe me, the knowledge I have gained has had a profound influence.

What does the customer value? may be the most important question.

Yet it is the one least often asked.

Nonprofit leaders tend to answer it for themselves.

“It’s the quality of our programs.

It’s the way we improve the community.”

People are so convinced they are doing the right things and so committed to their cause that they come to see the institution as an end in itself.

But that’s a bureaucracy.

Instead of asking, “Does it deliver value to our customers?” they ask, “Does it fit our rules?”

And that not only inhibits performance but also destroys vision and dedication.

— Peter Drucker,

The Five Most Important Questions …

Quality

Quality in a product or service is not what the supplier puts in.

It is what the customer gets out and is willing to pay for.

A product is not quality because it is hard to make and costs a lot of money, as manufacturers typically believe.

This is incompetence.

Customers pay only for what is of use to them and gives them value.

Nothing else constitutes quality.

— Peter Drucker

The Logic Bubble

I (Edward de Bono) created the term ‘logic bubble’ in a previous book.

When someone does something you do not like or with which you do not agree, it is easy to label that person as stupid, ignorant or malevolent.

But that person may be acting ‘logically’ within his or her ‘logic bubble’.

That bubble is made up of the perceptions, values, needs and experience of that person.

If you make a real effort to see inside that bubble and to see where that person is ‘coming from’, you usually see the logic of that person’s position.

In the school programme for teaching thinking (CoRT (Cognitive Research Trust) programme) there are tools which broaden perception so the thinker sees a wider picture and acts accordingly.

One of these tools is OPV, which encourages the thinker to ‘see the Other Person’s Point of View’.

We have numerous examples where a serious fight came to a sudden end when the combatants (who had learned the methods) decided to do an OPV on each other, a very similar process to understanding the ‘logic bubble’ of the other party.

— Edward de Bono

Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything (P.S.)

Communications

About organizations and employment

Every organization has an entity idea and operations that implement the idea. When the idea becomes inappropriate (competitive impotence, obsolescence) there is no reason for the operations to exist.

From Management, Revised Edition by Peter Drucker

… But while the life expectancy of the individual and especially the individual knowledge worker has risen beyond anything anybody could have foretold at the beginning of the twentieth century, the life expectancy of the employing institution has been going down, and is likely to keep going down. Or rather, the number of years has been shrinking during which an employing institution—and especially a business enterprise—can expect to stay successful. This period was never very long. Historically, very few businesses were successful for as long as thirty years in a row. To be sure, not all businesses ceased to exist when they ceased to do well. But the ones that survived beyond thirty years usually entered into a long period of stagnation—and only rarely did they turn around again and once more become successful growth businesses.

Thus, while the life expectancies and especially the working-life expectancies of the individual and especially of the knowledge worker have been expanding very rapidly, the life expectancy of the employing organizations has actually been going down. And—in a period of very rapid technological change, of increasing competition because of globalization, of tremendous innovation—the successful life-expectancies of employing institutions are almost certain to continue to go down. More and more people, and especially knowledge workers, can therefore expect to outlive their employing organizations and to have to be prepared to develop new careers, new skills, new social identities, new relationships, for the second half of their lives.

And now the largest single group in the workforce in all developed countries is knowledge workers rather than manual workers. At the beginning of the twentieth century, knowledge workers in any country, even the most highly developed ones, were very scarce. I doubt that there was any country in which they exceeded 2 or 3 percent of the working population. Now, in the United States, they account for around 33 percent of the working population. By the year 2020, they will account for about the same proportion in Japan and in Western Europe. They are something we have never seen before. These knowledge workers own their means of production, for they own their knowledge. And their knowledge is portable; it is between their ears.

For untold millennia, there were no choices for the overwhelming majority of people in any country. A farmer’s son became a farmer. A craftsman’s son became a craftsman, and a craftsman’s daughter married a craftsman; a factory worker’s son or daughter went to work in a factory. Whatever mobility there was was downward mobility. In the 250 years of Tokugawa rule in Japan, for instance, very few people advanced from being commoners to being samurai—that is, privileged warriors. An enormous number of samurai, however, lost their status and became commoners, that is, moved down. The same was true all over the world. Even in the most mobile of countries, the early twentieth-century United States, upward mobility was still the exception. We have figures from the early 1900s until 1950 or 1955. They show conclusively that at least nine out of every ten executives and professionals were themselves the sons of executives and professionals. Only one out of every ten executives or professionals came from the “lower orders” (as they were then called).

The business enterprise, as it was invented around 1860 or 1870—and it was an invention that had little precedent in history—was such a radical innovation precisely because there was upward mobility within it for a few people. This was the reason why the business enterprise ruptured the old communities—the rural village, the small town, or the craft guild.

But even the business enterprise, as it was first developed, tried to become a traditional community. It is commonly believed—in Japan as well as in the West—that the large Japanese company with its lifetime employment is some thing that exists only in Japan and expresses specific Japanese values. Apart from the fact that this is historical nonsense—lifetime employment in Japan even for white collar, salaried employees was a twentieth-century invention and did not exist before the end of Meiji (that is, before the twentieth century)—the large business enterprise in the West was not very different. Anyone who worked as a salaried employee for a large company in Germany, Great Britain, the United States, Switzerland, and so on had, in effect, lifetime employment. And even a salaried employee above the entry level in such a company considered himself “a company man” and identified himself with the company. He—and of course in those days they were all men—was a “Siemens Man” in Germany or a “General Electric Man” in the United States. Most of the big companies all over the West, just like the Japanese companies, hired people for only the entrance positions, and they expected them to stay until they died or retired. In fact, the Germans, with their passion for codifying everything, even created a category for such people. They were called “private civil servants” (Privatbeamte). Socially, they ranked below civil servants. But legally, they had the same job security and, in effect, lifetime employment—with the implicit assumption that they, in turn, would be committed to their employer for their entire working life and career. The Japanese company as it was finally formulated in the 1950s or early 1960s was, in other words, simply the most highly structured and most visible expression of the large business enterprise as it had been first developed in the late nineteenth-century and then reached full maturity in the first half of the twentieth century.

The early nineteenth-century business—and even the mid-nineteenth-century business—derived success from low costs. Successfully managing a business meant being able to produce the same commodities everybody else produced but at lower cost. In the twentieth century this then changed to what we now call “strategy” or analysis for the purpose of creating competitive advantage. I may claim to have been the first one to point this out, in a 1964 book called Managing for Results. But by that time a shift was already underway to another basic foundation: knowledge. [I had realized that in 1959—and the first result of this realization was my book The Effective Executive (1966). It was in that book that the shift to the knowledge worker was foreshadowed and its implication for the business first analyzed.]

The knowledge worker, to repeat, differs from any earlier worker in two major aspects. First, the knowledge worker owns the means of production and they are portable. Second, he or she is likely to outlive any employing organization. Add to this that knowledge work is very different in character from earlier forms of work. It is effective only if highly specialized. What makes a brain surgeon effective is that he is a specialist in brain surgery. By the same token, however, he probably could not repair a damaged knee. And he certainly would be helpless if confronted with a tropical parasite in the blood.

This is true for all knowledge work. “Generalists”—and this is what the traditional business enterprise, including the Japanese companies, tried to develop—are of limited use in a knowledge economy. In fact, they are productive only if they themselves become specialists in managing knowledge and knowledge workers. This, however, also means that knowledge workers, no matter how much we talk about “loyalty,” will increasingly and of necessity see their knowledge area—that is, their specialization rather than the employing organization—as what identifies and characterizes them. Their community will increasingly be people who share the same highly specialized knowledge, no matter where they work or for whom.

In the United States, as late as the 1950s or 1960s, when meeting somebody at a party and asking him what he did, one would get the answer, “I work for General Electric” or “for Citibank” or for some other employing organization. In other words, one would get exactly the same kind of answer in Germany, in Great Britain, in France, and in any other developed country. Today, in the United States, if one asks someone whom one meets at a party, “What do you do?” the answer is likely to be, “I am a metallurgist” or “I am a tax specialist” or “I am a software designer.” In other words, in the United States, at least, knowledge workers no longer identify themselves with an employer. They identify themselves with a knowledge area. The same is increasingly true in Japan, certainly among the younger people.

This is more likely to change the organization of the future, and especially the business enterprise, than technology, information, or e-commerce.

Since 1959, when I first realized that this change was about to happen, I consciously worked at thinking through the meaning of this tremendous change, and especially the meaning for individuals. For not only is it individuals who will have to convert this change into opportunity for themselves, for their careers, for their achievement, for their identification and fulfillment. It is the individual knowledge worker who, in large measure, will determine what the organization of the future will look like and which kind of organization of the future will be successful.

There is as a consequence only one satisfactory definition of management, whether we talk of a business, a government agency, or a nonprofit organization: to make human resources productive. It will increasingly be the only way to gain competitive advantage. Of the traditional resources of the economist—land, labor, and capital—none anymore truly confers a competitive advantage. To be sure, not to be able to use these resources as well as anyone else is a tremendous competitive disadvantage. But every business has access to the same raw materials at the same price. Access to money is worldwide. And manual labor, the traditional third resource, has become a relatively unimportant factor in most enterprises. Even in traditional manufacturing industries, labor costs are no more than 12 or 13 percent of total costs, so that even a very substantial advantage in labor costs (say a 5 percent advantage) results in a negligible competitive advantage except in a very small and shrinking number of highly labor-intensive industries (e.g., knitting woolen sweaters). The only meaningful competitive advantage is the productivity of the knowledge worker. And that is very largely in the hands of the knowledge worker rather than in the hands of management. Knowledge workers will increasingly determine the shape of the successful employing organizations.

What this implies is basically the topic of this book. These are very new demands. To satisfy them will increasingly be the key to success and survival for the individual and enterprise alike. To enable its readers to be among the successes—as executives in their organization, in managing themselves and others—is the primary aim of the revised edition of this book.

I suggest you read one chapter at a time—it is a long book.

And then first ask, “What do these issues, these challenges, mean for our organization and for me as a knowledge worker, a professional, an executive?”

Once you have thought this through, ask,

"What action should our organization and I, the individual knowledge worker and/or executive, take to make the challenges of this chapter into opportunities for our organization and me?”

… To be sure, these associates are subordinates in that they depend on the boss when it comes to being hired or fired, promoted, appraised, and so on. But in his or her own job the superior can perform only if these so-called subordinates take responsibility for educating him or her, that is, for making the superior understand what market research or physical therapy can do and should be doing, and what results are in their respective areas. In turn, these “subordinates” depend on the superior for direction; they depend on the superior to tell them what the score is.

Their relationship, in other words, is far more like that between the conductor of an orchestra and the instrumentalist than it is like the traditional superior-subordinate relationship. The superior in an organization employing knowledge workers cannot, as a rule, do the work of the supposed subordinate any more than the conductor of an orchestra can play the tuba. In turn, the knowledge worker dependent on the superior to give direction and, above all, to define what the score is for the entire organization—that is, what are the standards and values, performance and results. And just as an orchestra can sabotage even the ablest conductor and certainly even the most autocratic one—a knowledge organization can easily sabotage even the ablest, let alone the most autocratic, superior.

Altogether, an increasing number of people who are full-time employees have to be managed as if they were volunteers. They are paid, to be sure. But knowledge workers have mobility. They can leave. They own their means of production, which is their knowledge. What motivates—and especially what motivates knowledge workers—is what motivates volunteers. Volunteers, we know, have to get more satisfaction from their work than paid employees, precisely because they do not get a paycheck. They need, above all, challenge. They need to know the organization’s mission and to believe in it. They need continuous training. The need to see results.

Implicit in this is that different groups in the work population have to he managed differently, and that the same group in the work population has to be managed differently at different times. Increasingly, employees have to be managed as partners—and it is the definition of a partnership that all partners are equal. It is also the definition of a partnership that partners cannot be ordered. They have to be persuaded. Increasingly, therefore, the management of people is a marketing job. And in marketing one does not begin with the question, “What do we want?” One begins with the question, “What does the other party want? What are its values? What are its goals? What does it consider results?” And this is neither “Theory X” nor “Theory Y,” nor any other specific theory of managing people.

Maybe we will have to redefine the task altogether. It may not be “managing the work of people.” The starting point, both in theory and in practice, may have to be “managing for performance.” The starting point may be a definition of results—just as the starting points of both the orchestra conductor and the football coach are the score.

The productivity of the knowledge worker is likely to become the center of the management of people, just as the work on the productivity of the manual worker became the center of managing people a hundred years ago, that is, since Frederick W. Taylor. This will require, above all, very different assumptions about people in organizations and their work:

One does not “manage” people. The task is to lead people.

And the goal is to make productive the specific strengths and knowledge of each individual.

The Shakeout (calendarize this?)

The “shakeout” sets in as soon as the “window” closes.

And the majority of ventures started during the “window” period do not survive the shakeout, as has already been shown for such high-tech industries of yesterday as railroads, electrical apparatus makers, and automobiles.

As these lines are being written, the shakeout has begun among microprocessor, minicomputer, and personal computer companies—only five or six years after the “window” opened.

Today, there are perhaps a hundred companies in the industry in the United States alone.

Ten years hence, by 1995, there are unlikely to be more than a dozen left of any size or significance.

But which ones will survive, which ones will die, and which ones will become permanently crippled—able neither to live nor to die—is unpredictable.

In fact, it is futile to speculate.

Sheer size may ensure survival.

But it does not guarantee success in the shakeout, otherwise Allied Chemical rather than DuPont would today be the world’s biggest and most successful chemical company.

In 1920, when the “window” opened for the chemical industry in the United States, Allied Chemical looked invincible, if only because it had obtained the German chemical patents which the U.S. government had confiscated during World War I.

Seven years later, after the shakeout, Allied Chemical had become a weak also-ran.

It has never been able to regain momentum.

No one in 1949 could have predicted that IBM would emerge as the computer giant, let alone that such big, experienced leaders as G.E. or Siemens would fail completely.

No one in 1910 or 1914 when automobile stocks were the favorites of the New York Stock Exchange could have predicted that General Motors and Ford would survive and prosper and that such universal favorites as Packard or Hupmobile would disappear.

No one in the 1870s and 1880s, the period in which the modern banks were born, could have predicted that Deutsche Bank would swallow up dozens of the old commercial banks of Germany and emerge as the leading bank of the country.

That a certain industry will become important is fairly easy to predict.

There is no case on record where an industry that reached the explosive phase, the “window” phase, as I called it, has then failed to become a major industry.

The question is, Which of the specific units in this industry will be its leaders and so survive?

This rhythm—a period of great excitement during which there is also great speculative ferment, followed by a severe “shakeout”—is particularly pronounced in the high-tech industries.

In the first place, such industries are in the limelight and thus attract far more entrants and far more capital than more mundane areas.

Comments by Warren Buffett.

Also the expectations are much greater.

More people have probably become rich building such prosaic businesses as a shoe-polish or a watchmaking company than have become rich through high-tech businesses.

Yet no one expects shoe-polish makers to build a “billion-dollar business,” nor considers them a failure if all they build is a sound but modest family company.

(Managing the Family Business: see December 28 and 29 in The Daily Drucker)

High tech, by contrast, is a “high-low game,” in which a middle hand is considered worthless.

And this makes high-tech innovation inherently risky.

But also, high tech is not profitable for a very long time.

The world’s computer industry began in 1947-48.

Not until the early 1980s, more than thirty years later, did the industry as a whole reach break-even point.

To be sure, a few companies (practically all of them American, by the way) began to make money much earlier.

And one, IBM, the leader, began to make a great deal of money earlier still.

But across the industry the profits of those few successful computer makers were more than offset by the horrendous losses of the rest; the enormous losses, for instance, which the big international electrical companies took in their abortive attempts to become computer manufacturers.

And exactly the same thing happened in every earlier “high-tech” boom—in the railroad booms of the early nineteenth century, in the electrical apparatus and the automobile booms between 1880 and 1914, in the electric appliance and the radio booms of the 1920s, and so on.

One major reason for this is the need to plow more and more money back into research, technical development, and technical services to stay in the race.

High tech does indeed have to run faster and faster in order to stand still.

This is, of course, part of its fascination.

But it also means that when the shakeout comes, very few businesses in the industry have the financial resources to outlast even a short storm.

This is the reason why high-tech ventures need financial foresight even more than other new ventures, but also the reason why financial foresight is even scarcer among high-tech new ventures than it is among new ventures in general.

(Find “financial foresight” in Innovation and Entrepreneurship and see chapter 3 in The Changing World of the Executive)

There is only one prescription for survival during the shakeout: entrepreneurial management (described in Chapters 12-15).

What distinguished Deutsche Bank from the other “hot” financial institutions of its time was that Georg Siemens thought through and built the world’s first top management team.

What distinguished DuPont from Allied Chemical was that DuPont in the early twenties created the world’s first systematic organization structure, the world’s first long-range planning, and the world’s first system of management information and control.

Allied Chemical, by contrast, was run arbitrarily by one brilliant egomaniac.

But this is not the whole story.

Most of the large companies that failed to survive the more recent computer shakeout — G.E. and Siemens, for instance—are usually considered to have first-rate management.

And the Ford Motor Company survived, though only by the skin of its teeth, even though it was grotesquely mismanaged during the shakeout years.

Entrepreneurial management is thus probably a precondition of survival, but not a guarantee thereof.

And at the time of the shakeout, only insiders (and perhaps not even they) can really know whether a knowledge-based innovator that has grown rapidly for a few boom years is well managed, as DuPont was, or basically unmanaged, as Allied Chemical was.

By the time we do know, it is likely to be too late.

Innovation and Entrepreneurship

About the global (transnational) dimension

Global (transnational) is broader than importing and exporting today's stuff. Pretend you live in nation X and have "business interests" in nations A, B, C, D … Does it make sense that you would want any of your business interests to under-perform or fail? Couldn't it be said that you have a global interest that exceeds your local, regional or national interest? Resources exist globally, markets exist globally, customers exist globally. The globalism that exists today is even broader and more complex than the pretend example above. The globalism of tomorrow will be different. And the day after tomorrow … The X-economy …

Some sports such as tennis have been global for quite awhile. The players come from a variety of nations. They play in a variety nations. The products they endorse are promoted globally. They are compensated in several currencies. They are seen on TV all over the world.

Some contend that the world depends on U.S. consumption fueled by debt.

The A.T. Kearney Global Champions 2009

There's a buzz phrase going around: "Think global; act local"

About the knowledge dimension

Post-Capitalist Society by Peter Drucker

EVERY FEW HUNDRED YEARS in Western history there occurs a sharp transformation. We cross what in an earlier book (The New Realities - 1989). I called a "divide." Within a few short decades, society rearranges itself-its world view; its basic values; its social and political structure; its arts; its key institutions. Fifty years later, there is a new world. And the people born then cannot even imagine the world in which their grandparents lived and into which their own parents were born. We are currently living through just such a transformation. It is creating the post-capitalist society, which is the subject of this book.

…

The same forces which destroyed Marxism as an ideology and Communism as a social system are, however, also making Capitalism obsolescent. For two hundred and fifty years, from the second half of the eighteenth century on, Capitalism was the dominant social reality. For the last hundred years, Marxism was the dominant social ideology. Both are rapidly being superseded by a new and very different society.

The new society—and it is already here—is a post-capitalist society. This new society surely, to say it again, will use the free market as the one proven mechanism of economic integration. It will not be an "anti-capitalist society." It will not even be a "non-capitalist society"; the institutions of Capitalism will survive, although some, such as banks, may play quite different roles. But the center of gravity in the post-capitalist society—its structure, its social and economic dynamics, its social classes, and its social problems—is different from the one that dominated the last two hundred and fifty years and defined the issues around which political parties, social groups, social value systems, and personal and political commitments crystallized.

The basic economic resource—"the means of production," to use the economist's term—is no longer capital, nor natural resources (the economist's "land"), nor "labor." It is and will be knowledge. The central wealth-creating activities will be neither the allocation of capital to productive uses, nor "labor"—the two poles of nineteenth- and twentieth-century economic theory, whether classical, Marxist, Keynesian, or neo-classical. (See Toward The Next Economics and other Essays) Value is now created by "productivity" and "innovation," both applications of knowledge to work. The leading social groups of the knowledge society will be "knowledge workers"—knowledge executives who know how to allocate knowledge to productive use just as the capitalists knew how to allocate capital to productive use; knowledge professionals; knowledge employees. (see The New Productivity Challenge) Practically all these knowledge people will be employed in organizations. Yet, unlike the employees under Capitalism, they will own both the "means of production" and the "tools of production"—the former through their pension funds (see "The Impact of Pension Funds on Corporate Governance" in Management, Revised Edition), which are rapidly emerging in all developed countries as the only real owners; the latter because knowledge workers own their knowledge and can take it with them wherever they go.

The economic challenge of the post-capitalist society will therefore be the productivity of knowledge work and the knowledge worker. (See "Knowledge: Its Economics and its Productivity" in Post-Capitalist Society and "Managing the Work and Worker in Knowledge Work" in Management, Revised Edition) (Also see The New Productivity Challenge)

The social challenge of the post-capitalist society will, however, be the dignity of the second class in post-capitalist society: the service workers. Service workers, as a rule, lack the necessary education to be knowledge workers. And in every country, even the most highly advanced one, they will constitute a majority.

The post-capitalist society will be divided by a new dichotomy of values and of aesthetic perceptions. It will not be the "Two Cultures"—literary and scientific—of which the English novelist, scientist, and government administrator C. P. Snow wrote in his The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution (1959), though that split is real enough. The dichotomy will be between "intellectuals" and "managers," the former concerned with words and ideas, the latter with people and work. To transcend this dichotomy in a new synthesis will be a central philosophical and educational challenge for the post-capitalist society. …

…

This change means that we now see knowledge as the essential resource. Land, labor, and capital are important chiefly as restraints. Without them, even knowledge cannot produce; with out them, even management cannot perform. But where there is effective management, that is, application of knowledge to knowledge, we can always obtain the other resources. That knowledge has become the resource, rather than a resource, is what makes our society "post-capitalist." This fact changes—fundamentally—the structure of society. It creates new social and economic dynamics. It creates new politics.

…

But in the knowledge society, even low-skilled service workers are not "proletarians." Collectively, the employees own the means of production. Individually, few of them are wealthy. Even fewer of them are rich (though a good many are financially independent—what we now call "affluent"). Collectively, however, whether through their pension funds, through mutual funds, through their retirement accounts, and so on, they own the means of production. The people who exercise the voting power for the employees are themselves employees; take, for example, the civil servants who manage the pension funds of state and local governments in the United States. These pension fund managers are the only true "capitalists" in the United States. The "capitalists" have thus themselves become employees in the post-capitalist knowledge society. They are paid as employees; they think as employees; they see themselves as employees. But they act as capitalists.

One implication is that capital now serves the employee, where under Capitalism the employee served capital. But a second implication is that we now have to redefine the role, power, and function of both capital and ownership. As we shall see in the next chapter (Post-Capitalist Society), we have to rethink the governance of corporations. (Also see "The Impact of Pension Funds on Corporate Governance" in Management, Revised Edition

Realities

Basic business realities

Today's major economic problem is overcapacity in most of the world's industries. Customers are scarce, not products. Demand, not supply, is the problem. Overcapacity leads to hyper competition, with too many goods chasing too few customers. And most goods and services lack differentiation—read more—Philip Kotler. See Marketing in Crisis

From Peter Drucker's Effective Executive

Enormous resources are brought together in the modern large business, in the modern large government agency, in the modern large hospital, or in the university; yet:

- far too much of the result is mediocrity,

- far too much is splintering of efforts,

- far too much is devoted to yesterday or to avoiding decision and action.

Organizations as well as executives need to work systematically on effectiveness and need to acquire the habit of effectiveness.

- They need to learn to feed their opportunities and to starve their problems.

- They need to work on making strength productive.

- They need to concentrate and to set priorities instead of trying to do a little bit of everything.

The organs of the economy and their strategic thought and action chain

Economic performance statistics and other observations (large pdf file).

Some observations by Warren Buffett.

The financial and money dimension:

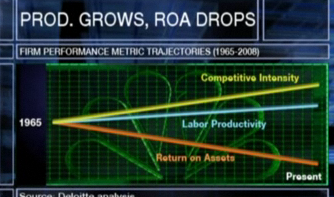

The Shift Index 2009: Industry Metrics and Perspectives

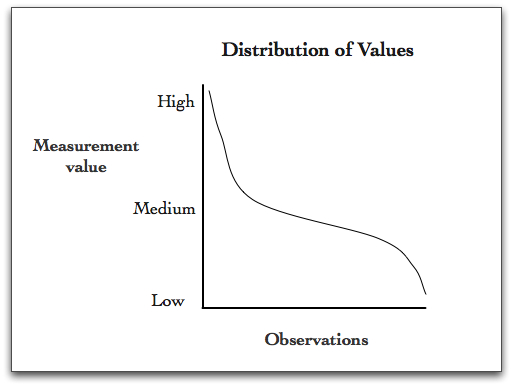

Forbes Magazine (The Capitalist Tool) publishes an annual industry survey which reports business profitability, growth and other performance measures. Within the industry groups and between groups the value distributions form a curve similar to the one below.

A long-term, simplified view of the economy as a provider of benefits for consumers

Intel connections: Fortune and Forbes lists (The Forbes Global 2000, 500s, Annual industry survey, Richest list, etc.); New stories; downsizing and layoffs; Non-employer: establishments and receipts.

Conceptual resource topic areas reflected in the economy: Management, marketing, quality, innovation, competition, and knowledge specialities. Try superimposing on the worlds of yesterday.

Conceptual resource directory list.

Specific books:

- The Definitive Drucker

- The Definitive Drucker

- Endorsements

- Title and copyright info

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword by A.G. Lafley Chairman, President, and CEO P&G

- Introduction by Elizabeth Haas Edersheim

- A call from Peter Drucker

- An already full schedule

- Twenty-first century realities

- The shaping and creation of this book

- Peter Drucker' liberating impact

- Drucker Ideas

- Book & chapter overviews

- Drucker's declarations

- Drucker Philosopy

- Efficiency vs. Effectiveness

- On Money

- On Management

- On Knowledge

- On the Individual

- Doing Business in the Lego World

- The Silent Revolution

- First, information flew

- Second, the geographic reach of companies and customers exploded

- Third, basic demographic assumption were upended

- Fourth, customers stepped up and took control

- Finally, defining walls fell

- The impact of this silent revolution hit me one day in 2005

- Embracing The Future

- The Primacy Of Knowledge

- The Lego World

- A New Solution Space

- Implications For Managers

- Conclusion

- The Customer: Joined at the Hip

- Medtronic

- Connecting With Your Customer: Four Drucker Questions

- Who Should Be Considered A Customer?

- Ideas In Action: Shadow Customers

- Customer Versus Competitor?

- Who Is Not Your Customer?

- Which Of Your Current Noncustomers Should You Be Doing Business With?

- What Does Your Customer Consider Value?

- Does Your Customer's Perception Of Value Align With Your Own?

- How Do Connectivity And Relationships Influence Value?

- Which Customer Wants Remain Unsatisfied?

- What Are Your Results With Customers?

- How Are You Measuring Your Outside Results?

- How Are Outsiders Measuring And Sharing Results And Information …

- Are You Fully Leveraging The Information Your Results Provide?

- Are You Honest And Socially Responsible In Presenting Your Results?

- An enterprise needs to examine the ethical dimension

- Perils of the inside-out approach

- Outside-in perspective

- Individualized strategies

- Does Your Customer Strategy And Your Business Strategy Work Together?

- Procter & Gamble

- The Grandfather Of Marketing

- Conclusion

- Innovation and Abandonment

- Creating Your Tomorrow: Four Drucker Questions

- What Do You Have To Abandon To Create Room For Innovation?

- If You Weren't In This Business Today, Would You Invest The Resources To Enter It?

- What Unconscious Assumptions Limit Your Innovative Thinking?

- Are Your Highest-Achieving People Assigned To Innovative Opportunities?

- Do You Systematically Seek Opportunities

- Do You Look For Opportunities As If Your Survival Depended On It?

- Are You Looking At The Seven Key Sources Of Opportunities?

- The Unexpected

- Industry Disparities across Time or Geography

- Incongruities

- Process Vulnerabilities

- Demographic Changes

- Perception and Priority Changes That Shift Buying Habits

- New Knowledge

- Collectively

- Do You Use A Disciplined Process For Converting Ideas Into Practical Solutions?

- Do You Brainstorm Effectively?

- Do You Match Up Ideas With The Opportunity?

- Do You Test And Refine Ideas Based On The Market Response?

- Do You Deliver The Results?

- Does Your Innovation Strategy Work With Your Business Strategy?

- What Is Your Company's Target Role In Defining New Markets?

- Do Your Opportunities Fit With Your Business Strategy?

- Are You Allocating Resources Where You Want To Be Making Bets?

- How Innovation Enables GE's Longevity And Valuation

- Making Innovation Everyone's Business

- In Contrast To GE: Siemens AG

- Different Cultures

- Differing Results

- Conclusion

- Collaboration and Orchestration

- Peter's vision of collaboration

- The Power Of Collaboration

- Collaboration And Orchestration: Three Drucker Questions

- Three Groups of Drucker Questions

- Goals

- What Are The Goals Of Your Collaboration?

- Structure

- How Should The Collaboration Be Structured?

- Operate and Orchestrate

- How Can You Orchestrate Your Collaboration to ...

- Some unmet needs are simply not possible without collaboration

- Service and Gadget Connections

- Seamless Wireless Coverage

- Barriers of the Prevailing Academic Model

- Barriers between the Private-Sector and the Academic World

- Dell Example

- Example from Developing Countries

- Identify your "Front Room" and Outsource the Rest

- Myelin Repair Foundation Approach

- Linux Example

- Toshiba Example

- More Drucker Thoughts

- Create A Living Business Plan

- Structure Communications For Agile Decision Making

- Track Progress As Measured By Expected Results

- Evolving Business Models

- Adaptation and Orchestration at LM Ericsson

- Learning the Nuances of Working with Japanese Partners

- Conclusion

- People and Knowledge

- Drucker's People First Thinking

- Feedback from Drucker Clients

- Alcoa and People (example)

- Drucker's Basic People Views

- Drucker listed five rules for making hiring decisions:

- Look at a number of potentially qualified people

- Think hard about what each candidate brings to the position and the organization

- Have a variety of people get to know the candidate as a person

- Discuss each of the candidates with several people who have worked with them

- After the hire, follow up to make sure the appointee understands the job

- Investing In People And Knowledge: Five Drucker Questions

- Who Are The Right People For Your Organization?

- What Is The Task?

- What Knowledge And Working Style Will Help An Individual Win?

- Breadth of Experience--Lou Gerstner example

- The Conference Board example

- Are You Accessing The Full Diversity Of The Population?

- Are You Providing Your People With The Means To Make Their Maximum Contribution To The Organization'

- Is There A Clear Mission And Direction That Builds Commitment?

- Clairol example

- A mission statement should fit on your T-shirt

- Palo Alto Research Center example

- Are People Given Autonomy And Support?

- Are You Playing To People's Strengths Rather Than Managing Around Their Problems?

- Do Your Structure And Processes Institutionalize Respect For And Investment In Human Capital?

- Do You Systematically Match Strengths With Opportunities?

- Do Your Structure And Processes Maximize The Knowledge Worker's Contribution And Productivity?

- Whole Foods example

- Examples from U.S. health-care system

- Do You Systematically Develop Employees?

- Is Knowledge And Access To Knowledge Built Into Your Way Of Doing Business?

- Is Knowledge Built Into Your Customer Connection?

- Is Knowledge Built Into Your Innovation Process?

- Is Knowledge Built Into Your Collaborations?

- Is Knowledge Built Into Your People And Knowledge Management?

- Bain & Company example

- Leap-frogging the consultants

- A knowledge world view

- What Is Your Strategy For Investing In People And Knowledge?

- Knowledge and a specific company

- Four types of knowledge strategy

- The knowledge provider

- The service provider

- The commodity player

- The relationship-dependent connector

- Summary (rename)

- Electrolux example: Using Talent Management To Accelerate Strategic Change

- Background

- A Changing World (for Electrolux)

- Knowledge, Information, People and Organizations

- Polaroid example

- Every enterprise must build knowledge into its value proposition

- How People Make The Difference At Edward Jones

- Google's 10 Golden Rules For Knowledge Workers

- 1. Hire by committee

- 2. Cater to their every need

- 3. Pack them in

- 4. Make coordination easy

- 5. Eat your own dog food

- 6. Encourage creativity

- 7. Strive to reach consensus

- 8. Don't be evil

- 9. Data drives decisions

- 10. Communicate effectively

- Conclusion

- Decision Making: The Chassis That Holds the Whole Together

- Examining/Exploring the Strategic and Unfolding Landscape

- Decision Making: The Right Risks

- Decision Making: Four Drucker Questions

- Have you built in time to focus on critical decisions--have you lightened your load?

- Is Action Required?

- Who Should Make The Decision?

- Does your culture support making the right decision with ready contingency plans?

- What's The Real Issue?

- What Specifications Must The Solution Meet?

- Have You Fully Considered All The Alternative Solutions?

- Guidelines for Choosing Alternatives

- Is The Organization Willing To Commit To The Decision Once It Is Made?

- As Decisions Are Made, Are Resources Allocated To "Degenerate Into Work"

- Have You Gained Commitment And Capacity Of The Implementers?

- Do You Have Mechanisms That Provide Tracking And Feedback?

- Clairol example

- The Decision Process

- Toyota Example

- How Toyota Gets Its Edge

- The Origins Of The Toyota Way

- How Toyota Makes Decisions

- Do the Homework First

- Look at All Solutions, Build Consensus among Stakeholders, and Set Sights High

- Implement Rapidly

- Decision Making By Alfred Sloan

- Conclusion

- The Twenty-First-Century CEO

- Field Of Vision

- On my first meeting with Frances Hesselbein

- The CEO Brand

- When Frank Weise became the CEO of Cott Beverage

- Influence On People--Collectively And Individually

- Summary

- Each Of Us As CEO

- Maintaining a broad field of vision

- Knowing yourself and what give you passion

- David Rockefeller example

- What should I contribute?

- Influencing--a two way street

- Managing our own lives

- Final Drucker thoughts

- Endnotes

- Books By Peter F. Drucker

- Acknowledgments

- Management, Revised Edition

- Part I: Management's New Realities

- Chapter 4: Knowledge Is All

- Knowledge Is the Key Resource in Society and Knowledge Workers Are the Dominant Group in the Workforce

- The Three Main Characteristics of Knowledge Economy

- The New Workforce

- His And Hers

- Ever Upward

- The Price Of Success

- Chapter 5: New Demographics

- The Sifting Age Structure

- Needed But Unwanted

- A Country Of Immigrants

- Splitting of Hitherto Homogeneous Societies and Markets

- The End Of The Single Market

- Beware Demographic Changes

- Chapter 6: The Future of the Corporation and the Way Ahead

- Five OUTDATED Basic Assumptions

- The corporation is the "master," the employee is the "servant."

- The great majority of employees work full-time for the corporation

- All activities under one management

- Suppliers have market power

- Technologies and industries are a unique set

- Everything In Its Place (Five NEW Assumptions)

- Who Needs A Research Lab?

- The Next Company

- From Corporation To Confederation

- General Motors Example

- The Toyota Way

- The Syndicate Model

- Top management's role

- Life At The Top

- The Way Ahead: The Time To Get Ready For The New Realities Is Now

- The future corporation

- People policies

- Outside information

- Change agents

- And Then?

- Information revolution in historical context

- The two industrial revolutions also bred new theories and new ideologies

- Big Ideas

- New Economic Regions

- Transnational financial organizations

- Schumpeter's postulates of dynamic disequilibrium

- The World of 2030: very different

- Chapter 7: Management's New Paradigm

Those who do work on these challenges today, and thus prepare themselves and their institutions for the new challenges, will be the leaders and dominate tomorrow.

Those who wait until these challenges have indeed become "hot" issues are likely to fall behind, perhaps never to recover.

This book is thus a Call for Action.

These challenges are not arising out of today. THEY ARE DIFFERENT …

In most cases they are at odds and incompatible with what is accepted and successful today.

We live in a period of PROFOUND TRANSITION and the changes are more radical perhaps than even those that ushered in the "Second Industrial Revolution" of the middle of the 19th century, or the structural changes triggered by the Great Depression and the Second World War.

READING this book will upset and disturb a good many people, as WRITING it disturbed me.

For in many cases—for example, in the challenges inherent in the DISAPPEARING BIRTHRATE in the developed countries, or in the challenges to the individual, and to the employing organization, discussed in the final chapter on MANAGING ONESELF—the new realities and their demands require a REVERSAL of policies that have worked well for the last century and, even more, a change in the MINDSET (mental patterns) of organizations as well as of individuals.

- Introduction (About Assumptions)

- Management Is Business Management

- Management is the specific and distinguishing organ of any and all organizations

- The One Right Organization

- Instead of searching for the right organization, management needs to learn to look for, to develop, to test: The organization that fits the task

- The One Right Way To Manage People

- One does not "manage" people.

- The task is to lead people.

- And the goal is to make productive the specific strengths and knowledge of each individual.

- Technologies And End-Users Are Fixed And Given

- Management, in other words, will increasingly have to be based on the assumption that neither technology nor end-use is a foundation for management policy.

- The foundations have to be customer values and customer decisions on the distribution of their disposable income.

- It is with those that management policy and management strategy increasingly will have to start

- Management's Scope Is Legally Defined

- The new assumption on which management, both as a discipline and as a practice, will increasingly have to base itself is that the scope of management is not legal.

- It has to be operational.

- It has to embrace the entire process.

- It has to be focused on results and performance across the entire economic chain.

- Management's Scope Is Politically Defined

- National boundaries are important primarily as restraints. The practice of management—and by no means for businesses only—will increasingly have to be defined operationally rather than politically.

- The Inside Is Management's Domain

- Management exists for the sake of the institution's results.

- It has to start with the intended results and has to organize the resources of the institution to attain these results.

- It is the organ to make the institution—whether business, church, university, hospital, or a battered women's shelter—capable of producing results outside of it.

- Final paradigm: Management's Concern and Responsibility

- Management is the specific tool, the specific function, the specific instrument, to make institutions capable of producing results.

- Management's concern and management's responsibility are everything that affects the performance of the institution and its results—whether inside or outside, whether under the institution's control or totally beyond it.

- Management Cases

- Innovation and Entrepreneurship

- Management Golf by Mike Kami (formerly headed strategic planning for IBM and Xerox during their high growth periods);

- Competitive Advantage by Michael Porter;

- Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies by Jim Collins and Jerry I. Porras

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die

- Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap … and Others Don't by Jim Collins

- Creating Strategic Leverage by Milind Lee;

- Marketing Warfare by Al Ries and Jack Trout;

- Managing for Results by Peter Drucker;

- In Search of Excellence by Tom Peters and Robert Waterman;

- Sur/petition (Going beyond competition);

- Competing for the Future by Gary Hamel and C.K. Prahalad;

- Crazy Times Call for Crazy Organizations by Tom Peters

Where and how thoroughly are these resources included in MBA, executive development or continuing education programs?

How adequately do the concepts present in the economic content and structure at a point in time explain what actually happens in time? Do they naturally lead to a healthy future?.

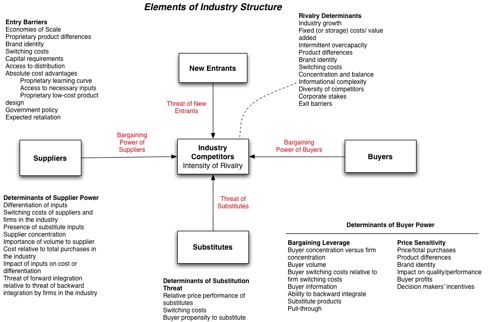

A view of industry structure

The following appeared in a November 2003 Internet posting: Motorola spinning off semiconductor business—Baffling. Does anyone but me find Motorola's announcement that it will spin off its semiconductor business a bit peculiar? How does a company manage to create and pioneer early markets, dominate, and then give up on the market? I'm talking about radios, TVs, and microprocessors, including RISC chips. When will the company bail on the cell-phone market it largely created? This is a weird business model. My advice to Motorola is to change the name to Motorola Market Development Company. It would make more sense.

2011 Follow-up: "Motorola Solutions Inc. and Motorola Mobility Holdings Inc., the two companies that split from each other this year, increased the pay of the chief executive officers who oversaw the separation …"

What realities of economic content and structure would a month's programing on the History Channel reveal?

Organization evolution definition

See industry evolution in Michael Porter's Competitive Strategy.

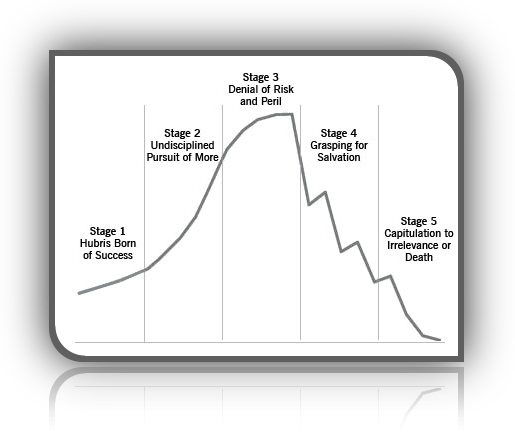

Growth industry dynamics: … Even from the purely financial point of view of the investor interested in capital gains, the growth company is not a sound investment. Such a company sooner or later—and usually sooner—runs into real difficulties. Sooner or later it runs into tremendous losses, has to write off vast sums, and becomes, in effect, unmanageable. It takes years then for such a company to regain its health and its capacity to grow again and to produce profit. There are few exceptions to the rule that today's growth company is tomorrow's problem.

The same vulnerability characterizes the "growth industry." Indeed the dynamics of a growth industry are perfectly well known—and they make the growth industry a poor investment except for the most knowledgeable. In the growth industry there is first the opening up of a new major area of economic activity which promises to offer tremendous opportunities. Any entrant into this new area of activity seems to be doing very well. As a result, a great many new entrants clamor to get into the act. Soon the industry is overcrowded. Inevitably there is then a "shakeout." Where there were thirty or forty entrants, only five or six, maybe seven or eight, remain. Of these, three or four assume leadership and retain it for many decades. Another three or four manage to become respectable fair-sized businesses, occupying small but distinct niches. The rest disappear. But which companies will emerge as leaders in this process and which will disappear is unpredictable. Even the insider has little chance to guess correctly. The decisive factor is well hidden. It is, above all, the capacity of a company's management to manage for growth and to develop the strategy that will give it leadership position in the shake-out. — From Chapter 60, Managing Growth in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices by Peter Drucker.

See Warren Buffett

Marketing in Crisis (Marketing and Innovation in a society moving in time).

Dealing with risk and uncertainty

The brain is a history library that has to run in the future tense.

Almost all our thinking activity is directed towards dealing with the future since all actions taken are directed towards bringing about an effect which is not yet present.

Yet the brain can only make observations of the moment and recall experience of the past—[both shaped by mental patterns].

Even what we see at the moment is conditioned by the perceptions [mental patterns] of the past.

Our habit of analysis has been developed in order to break down unfamiliar chunks.

We seek to discover scientific truths so that we may predict what will happen and how we can make things happen with a practical degree of certainty.

We are forever extrapolating the past [our perception of it] in order to prepare the future [shaped by other people's perceptions] into which we are always moving.

It is not surprising that much of business is dealing with risk and uncertainty because all of business is dealing with the future.

When we concern ourselves with opportunity we are dealing with greater risk and uncertainty because we have to do much more than predict that an already existing business will go on being successful (the minimal prediction anyone has to make—and it is increasingly difficult to make).

Edward de Bono

Opportunities

Thinking about progress : An issue, need or undesirable situation exists: In time we want to be able to … diagnose it > treat it > completely fix it > prevent it > create a perfect situation > design a perfect life (not possible because human's are perpetual wanting "machines") … and then something new and different emerges.

Employees and employment

Truth is we're all entering this job market for the first time. Nobody has ever seen a job market like this one before. Picking a safe profession, working for a big company, moving to where the jobs are, none of those standard practices of the last 50 years seem to be as effective as they once were. Maybe it's time to try something totally different. What is there to lose?

The idea of a safe profession has no meaning in a global economy where there is a practically endless supply of talent in almost all professions. Working for a big company doesn't seem to be any less risky than working for a small company since so many big companies are constantly restructuring and shedding business units and employees. And since jobs are less tied to geographical locations than they used to be, chasing hot job markets guarantees you ll have to move every two or three years. So if the level of competition and risk is high wherever you go, perhaps the best approach is to go where you want to live and do work that you find to be interesting (regardless of traditional concerns).

Economic content and structure is somewhat reflected in the visible : An ancient city vs. a "modern" city. The elements of life design.

Moving Beyond Capitalism?

… Of late, some of capitalism’s biggest boosters, people such as yourself and the financier George Soros, have become its biggest critics. What is your critique?

I am for the free market. Even though it doesn’t work too well, nothing else works at all. But I have serious reservations about capitalism as a system because it idolizes economics as the be-all and end-all of life. It is one-dimensional.

For example, I have often advised managers that a 20-1 salary ratio is the limit beyond which they cannot go if they don’t want resentment and falling morale to hit their companies. I worried back in the 1930s (The End of Economic Man) that the great inequality generated by the Industrial Revolution would result in so much despair that something like fascism would take hold. Unfortunately, I was right.

Today, I believe it is socially and morally unforgivable when managers reap huge profits for themselves but fire workers. As societies, we will pay a heavy price for the contempt this generates among the middle managers and workers.

In short, whole dimensions of what it means to be a human being and treated as one are not incorporated into the economic calculus of capitalism. For such a myopic system to dominate other aspects of life is not good for any society.

With regard to the market, there are several serious problems with the theory itself.

First of all, the theory assumes there is one homogeneous market. In reality, there are three overlapping markets that, by and large, don’t interchange: an international market in money and information, national markets, and local markets.

Most of what passes for transnational economic money, of course, is only virtual money.

The London interbank market each day has a greater volume of activity in dollar terms than the whole world would need for a year to finance all economic transactions.

This is functionless money. It cannot possibly earn any return since it serves no function. It has no purchasing power. It is, therefore, totally speculative and prone to panics as it rushes here and there to earn that last 64th of 1 percent.

Then, there is a large national economy which is not exposed to international commerce. Some 24 percent of U.S. economic activity is exposed to trade. In Japan, it is only 8 percent.

Then there is the local economy. The hospital near my home has very high-quality care and is very competitive. But it does not compete with any hospital forty miles away in Los Angeles. The effective market area for hospitals in the U.S. is about ten miles because, for some obscure reason no economist would be able to figure out, people like to be close to their sick mothers.

Also, what drives markets has changed. The economic center of gravity shifted sometime during this century. In the nineteenth century, with steel and steam, supply generated demand. Since the Great Depression, however, the tables have turned: In traditional products, from home construction to cars, demand must come before supply although this is not yet true today of information and electronics, which stimulate demand.

Beyond this definition of markets, the truly profound issue is that market theory is based on an assumption of equilibrium and thus cannot accommodate change, let alone innovation.

Rather, the real pattern of economic activity, as Joseph Schumpeter recognized as long ago as 1911, is “a moving disequilibrium” caused by the process of creative destruction as new markets with new products and new demand are made at the expense of old ones.

Market outcomes cannot, therefore, be explained in terms of what the theory would have predicted. The market is in fact not a predictable system, but inherently unstable. And if it is not predictable, you cannot base your behavior on it. That is a pretty serious limitation for a theory of human behavior.

All we can say is that, in the end, any long-term equilibrium is the result of a lot of short-term adaptations to market signals.

This, finally, is the strength of the market: It is a disciplinarian for the short term. By providing feedback through prices, it discourages you from squandering time and resources going off in all directions like King Arthur’s knights.

The old idea was that if you rode on long enough you would run into something. The market tells you that if you don’t run into something in five weeks, you better change course or do something else.

Beyond the short term, the market is useless. You know, I have sat in on more than my share of research planning for large companies. Fundamentally, this activity is an act of faith. When the chief financial officer asks, as he always does, “What will be the return?” on this or that project, the only answer is “We will know in ten years.”

Years ago you wrote about pension fund ownership of the American economy, calling it “capitalism sans capitalists” where workers’ retirement funds own the means of production. Today, this dispersion of wealth has gone even further through the explosion of mutual funds—more than 51 percent of Americans own shares of stock. Have we arrived at mass capitalism or post-capitalism?

Well, to call it post-capitalism is merely to say we don’t know what to call it.

You also can’t call it economic democracy since there is no organized form of governance associated with this mass ownership.

What is certain is that it is a totally new phenomenon in history. …

Managing in the Next Society

Peter Drucker

Growth areas

Because the growth sector of a developed society in the 21st century is most unlikely to be business—in fact, business has not even been the growth sector of the 20th century in developed societies.

A far smaller proportion of the working population in every developed country is now engaged in business than it was a hundred years ago.

Then virtually everybody in the working population made his living in economic activities (mostly farming).

The growth sectors in the 20th century in developed countries have been in nonbusiness—in government, in the professions, in health care, in education.

In the 21st century that trend is going to continue with a vengeance.

So the nonprofit social sector is where management (and here) is today most needed and where systematic, principled, theory-based management can yield the greatest results fastest.

Just think of the enormous problems facing the world—poverty, health care, education, international tension—and the need for managed solutions becomes loud and clear.

— Management’s new paradigms

It’ll (health care) be a growth sector simply because health care and education together will be 40 percent of the gross national product within twenty years.

Already, they’re at least a third.

Furthermore, as more and more services by government agencies will be outsourced, it will make little difference whether the organization which gets a contract to clean the streets is for profit or not for profit.

It won’t be in the market economy.

If I could voice one comment on your magazine and the present e-commerce and e-business-to-business concern altogether, it’s so far focused on business.

Yet I think the greatest e-commerce impact may be in higher education and health care.

— Drucker on Asia

More conceptual connections:

- New thinking about thinking

- See "From Analysis to Perception" in The Essential Drucker (ted.pdf::society:::From analysis to perception). Also see Water Logic to further explore perception

- What concepts are at work in the economy? What concepts will be effective tomorrow?

- Toward new organizations

- Post Capitalist Society

- Management Challenges for the 21st Century

- Managing in the Next Society

- Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices (Revised Edition)

- Managing Oneself

On Leadership from "Peter Drucker's Legacy" in Management, Revised Edition

During a discussion in graduate school, a professor challenged my first-year class: managers and leaders—are they different? The conversation unfolded something like this:

"Leaders set the vision; managers just figure out how to get there," said one student.

"Leaders inspire and motivate, whereas managers keep things organized," said another.

"Leaders elevate people to the highest values. Managers manage the details."

The discussion revealed an underlying worship of "leadership" and a disdain for "management." Leaders are inspired. Leaders are large. Leaders are the kids with black leather jackets, sunglasses, and sheer unadulterated cool. Managers, well, they're the somewhat nerdy kids, decidedly less interesting, lacking charisma. And of course, we all wanted to be leaders, and leave the drudgery of management to others.

We could not have been more misguided and juvenile in our thinking. As Peter Drucker shows right here, in these pages, the very best leaders are first and foremost effective managers. Those who seek to lead but fail to manage will become either irrelevant or dangerous, not only to their organizations, but to society.