Selected quotations from Benjamin Graham's Intelligent Investor

Who was Benjamin Graham?

Amazon link: The Intelligent Investor: The Definitive Book on Value Investing. A Book of Practical Counsel (Revised Edition)

Amazon search: Intelligent Investor

Outline of 1973 edition

Preview The Intelligent Investor at Google Book Search

Warren Buffett Returns to Columbia Campus Where He Learned About Value Investing

Also see Warren Buffett

Valuable time investment: Suggest readers extract the policy and action implications from the topics below and calendarize them.

The substantial rewards for doing this are covered below.

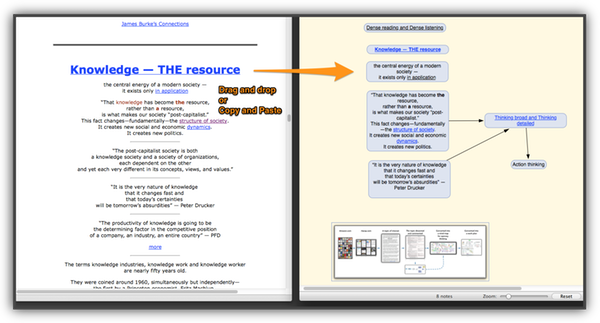

Larger view of image above. Thought collector and idea mapping

Calendarization (working something out in time)

The actual results of action are not predictable

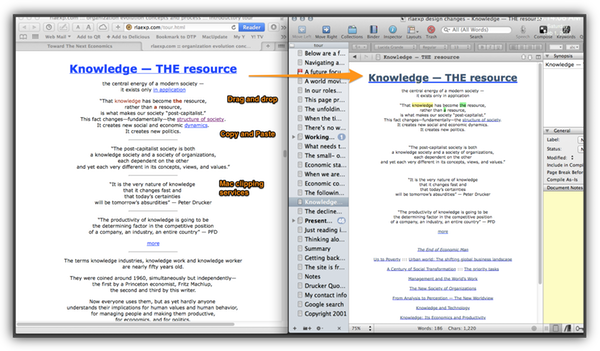

Larger view of image above

Organization actions: creating change to abandonment

Links to potential low cost fund alternatives can be found on bobembry's delicious financial investing page.

The art of investment has one characteristic that is not generally appreciated.

A creditable, if unspectacular, result can be achieved by the lay investor with a minimum of effort and capability; but to improve this easily attainable standard requires much application and more than a trace of wisdom.

If you merely try to bring just a little extra knowledge and cleverness to bear upon your investment program, instead of realizing a little better than normal results, you may well find that you have done worse.

Page topics

Summary from The Margin of Safety (the final chapter)

In the old legend the wise men finally boiled down the history of mortal affairs into the single phrase, "This too will pass."

Confronted with a like challenge to distill the secret of sound investment into three words, we venture the motto, MARGIN OF SAFETY.

This is the thread that runs through all the preceding discussion of investment policy—often explicitly, sometimes in a less direct fashion.

... snip, snip ...

Investment is most intelligent when it is most businesslike.

It is amazing to see how many capable businessmen try to operate in Wall Street with complete disregard of all the sound principles through which they have gained success in their own undertakings.

Yet every corporate security may best be viewed, in the first instance, as an ownership interest in, or a claim against, a specific business enterprise.

And if a person sets out to make profits from security purchases and sales, he is embarking on a business venture of his own, which must be run in accordance with accepted business principles if it is to have a chance of success.

The first and most obvious of these principles is, "Know what you are doing—know your business."

For the investor this means:

Do not try to make "business profits" out of securities—that is, returns in excess of normal, interest and dividend income—unless you know as much about security value as you would need to know about the value of merchandise that you proposed to manufacture or deal in.

A second business principle:

"Do not let anyone else run your business, unless

(1) you can supervise his performance with adequate care and comprehension or

(2) you have unusually strong reasons for placing implicit confidence in his integrity and ability."

For the investor this rule should determine the conditions under which he will permit someone else to decide what is done with his money.

A third business principle:

"Do not enter upon an operation—that is, manufacturing or trading in an item—unless a reliable calculation shows that it has a fair chance to yield a reasonable profit.

In particular, keep away from ventures in which you have little to gain and much to lose."

For the enterprising investor this means that his operations for profit should be based not on optimism but on arithmetic.

For every investor it means that when he limits his return to a small figure—as formerly, at least, in a conventional bond or preferred stock—he must demand convincing evidence that he is not risking a substantial part of his principal.

A fourth business rule is more positive:

"Have the courage of your knowledge and experience.

If you have formed a conclusion from the facts and if you know your judgment is sound, act on it—even though others may hesitate or differ."

(You are neither right nor wrong because the crowd disagrees with you.

You are right because your data and reasoning are right.)

Similarly, in the world of securities, courage becomes the supreme virtue after adequate knowledge and a tested judgment are at hand.

Fortunately for the typical investor, it is by no means necessary for his success that he bring these qualities to bear upon his program—provided he limits his ambition to his capacity and confines his activities within the safe and narrow path of standard, defensive investment.

To achieve satisfactory investment results is easier than most people realize; to achieve superior results is harder than it looks.

Introduction: What This Book Expects to Accomplish

The purpose of this book is to supply, in a form suitable for laymen, guidance in the adoption and execution of an investment policy.

Comparatively little will be said here about the technique of analyzing securities; attention will be paid chiefly to investment principles and investors' attitudes.

We shall, however, provide a number of condensed comparisons of specific securities—chiefly in pairs appearing side by side in the New York Stock Exchange list—in order to bring home in concrete fashion the important elements involved in specific choices of common stocks.

But much of our space will be devoted to the historical patterns of financial markets, in some cases running back over many decades.

To invest intelligently in securities one should be forearmed with an adequate knowledge of how the various types of bonds and stocks have actually behaved under varying conditions—some of which, at least, one is likely to meet again in one's own experience.

No statement is more true and better applicable to Wall Street than the famous warning of Santayana: "Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

Our text is directed to investors as distinguished from speculators, and our first task will be to clarify and emphasize this now all but forgotten distinction.

We may say at the outset that this is not a "how to make a million" book.

There are no sure and easy paths to riches in Wall Street or anywhere else.

It may be well to point up what we have just said by a bit of financial history—especially since there is more than one moral to be drawn from it.

In the climactic year 1929 John J. Raskob, a most important figure nationally as well as on Wall Street, extolled the blessings of capitalism in an article in the Ladies' Home Journal, entitled "Everybody Ought to Be Rich."

His thesis was that savings of only $15 per month invested in good common stocks—with dividends reinvested—would produce an estate of $80,000 in twenty years against total contributions of only $3,600.

If the General Motors tycoon was right, this was indeed a simple road to riches.

How nearly right was he?

Our rough calculation—based on assumed investment in the 30 stocks making up the Dow-Jones Industrial Average (DJIA)—indicates that if Raskob's prescription had been followed during 1929-1948, the investor's holdings at the beginning of 1949 would have been worth about $8,500.

This is a far cry from the great man's promise of $80,000, and it shows how little reliance can be placed on such optimistic forecasts and assurances.

But, as an aside, we should remark that the return actually realized by the 20-year operation would have been better than 8% compounded annually—and this despite the fact that the investor would have begun his purchases with the DJIA at 300 and ended with a valuation based on the 1948 closing level of 177.

This record may be regarded as a persuasive argument for the principle of regular monthly purchases of strong common stocks through thick and thin—a program known as "dollar-cost averaging."

Since our book is not addressed to speculators, it is not meant for those who trade in the market.

Most of these people are guided by charts or other largely mechanical means of determining the right moments to buy and sell.

The one principle that applies to nearly all these so-called "technical approaches" is that one should buy because a stock or the market has gone up and one should sell because it has declined.

This is the exact opposite of sound business sense everywhere else, and it is most unlikely that it can lead to lasting success in Wall Street.

In our own stock-market experience and observation, extending over 50 years, we have not known a single person who has consistently or lastingly made money by thus "following the market."

We do not hesitate to declare that this approach is as fallacious as it is popular.

We shall illustrate what we have just said—though, of course this should not be taken as proof—by a later brief discussion of the famous Dow theory for trading in the stock market.

Since its first publication in 1949, revisions of The Intelligent Investor have appeared at intervals of approximately five years.

In updating the current version we shall have to deal with quite a number of new developments since the 1965 edition was written.

These include:

1. An unprecedented advance in the interest rate on high-grade bonds.

2. A fall of about 35% in the price level of leading common stocks, ending in May 1970. This was the highest percentage decline in some 30 years. (Countless issues of lower quality had a much larger shrinkage.)

3. A persistent inflation of wholesale and consumer's prices, which gained momentum even in the face of a decline of general business in 1970.

4. The rapid development of "conglomerate" companies, franchise operations, and other relative novelties in business and finance. (These include a number of tricky devices such as "letter stock,"' proliferation of stock-option warrants, misleading names, use of foreign banks, and others.)

5. Bankruptcy of our largest railroad, excessive short-and long-term debt of many formerly strongly entrenched companies, and even a disturbing problem of solvency among Wall Street houses.

6. The advent of the "performance" vogue in the management of investment funds, including some bank-operated trust funds, with disquieting results.

These phenomena will have our careful consideration, and some will require changes in conclusions and emphasis from our previous edition.

The underlying principles of sound investment should not alter from decade to decade, but the application of these principles must be adapted to significant changes in the financial mechanisms and climate.

Types of investors

In the past we have made a basic distinction between two kinds of investors to whom this book was addressed—the "defensive" and the "enterprising."

The defensive (or passive) investor will place his chief emphasis on the avoidance of serious mistakes or losses.

His second aim will be freedom from effort, annoyance, and the need for making frequent decisions.

The determining trait of the enterprising (or active, or aggressive) investor is his willingness to devote time and care to the selection of securities that are both sound and more attractive than the average.

Over many decades an enterprising investor of this sort could expect a worthwhile reward for his extra skill and effort, in the form of a better average return than that realized by the passive investor.

We have some doubt whether a really substantial extra recompense is promised to the active investor under today's conditions.

But next year or the years after may well be different.

We shall accordingly continue to devote attention to the possibilities for enterprising investment, as they existed in former periods and may return.

Growth Investing—a flawed approach?

It has long been the prevalent view that the art of successful investment lies first in the choice of those industries that are most likely to grow in the future and then in identifying the most promising companies in these industries.

(See Warren Buffett's exposition on the stock market) For example, smart investors—or their smart advisers—would long ago have recognized the great growth possibilities of the computer industry as a whole and of International Business Machines in particular.

And similarly for a number of other growth industries and growth companies.

But this is not as easy as it always looks in retrospect.

To bring this point home at the outset let us add here a paragraph that we included first in the 1949 edition of this book.

Such an investor may for example be a buyer of air-transport stocks because he believes their future is even more brilliant than the trend the market already reflects.

For this class of investor the value of our book will lie more in its warnings against the pitfalls lurking in this favorite investment approach than in any positive technique that will help him along his path.

The pitfalls have proved particularly dangerous in the industry we mentioned.

It was, of course, easy to forecast that the volume of air traffic would grow spectacularly over the years.

Because of this factor their shares became a favorite choice of the investment funds.

But despite the expansion of revenues—at a pace even greater than in the computer industry—a combination of technological problems and overexpansion of capacity made for fluctuating and even disastrous profit figures.

In the year 1970, despite a new high in traffic figures, the airlines sustained a loss of some $200 millions for their stockholders.

(They had shown losses also in 1945 and 1961.)

The stocks of these companies once again showed a greater decline in 1969-70 than did the general market.

The record shows that even the highly paid full-time experts of the mutual funds were completely wrong about the fairly short-term future of a major and nonesoteric industry.

On the other hand, while the investment funds had substantial investments and substantial gains in IBM, the combination of its apparently high price and the impossibility of being certain about its rate of growth prevented them from having more than, say, 3 % of their funds in this wonderful performer.

Hence the effect of this excellent choice on their overall results was by no means decisive.

Furthermore, many—if not most—of their investments in computer industry companies other than IBM appear to have been unprofitable.

From these two broad examples we draw two morals for our readers:

1. Obvious prospects for physical growth in a business do not translate into obvious profits for investors.

2. The experts do not have dependable ways of selecting and concentrating on the most promising companies in the most promising industries.

The author did not follow this approach in his financial career as fund manager, and he cannot offer either specific counsel or much encouragement to those who may wish to try it.

Investment versus Speculation: Results to Be Expected by the Intelligent Investor

This chapter will outline the viewpoints that will be set forth in the remainder of the book.

In particular we wish to develop at the outset our concept of appropriate portfolio policy for the individual, nonprofessional investor.

Investment versus Speculation

What do we mean by "investor"?

Throughout this book the term will be used in contradistinction to "speculator."

As far back as 1934, in our textbook Security Analysis, we attempted a precise formulation of the difference between the two, as follows:

"An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis promises safety of principal and an adequate return.

Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative."

While we have clung tenaciously to this definition over the ensuing 38 years, it is worthwhile noting the radical changes that have occurred in the use of the term "investor" during this period.

After the great market decline of 1929-1932 all common stocks were widely regarded as speculative by nature.

(A leading authority stated flatly that only bonds could be bought for investment.)

Thus we had then to defend our definition against the charge that it gave too wide scope to the concept of investment.

Now our concern is of the opposite sort.

We must prevent our readers from accepting the common jargon which applies the term "investor" to anybody and everybody in the stock market.

In our last edition we cited the following headline of a front-page article of our leading financial journal in June 1962:

SMALL INVESTORS BEARISH, THEY ARE SELLING ODD-LOTS SHORT

In October 1970 the same journal had an editorial critical of what it called "reckless investors," who this time were rushing in on the buying side.

These quotations well illustrate the confusion that has been dominant for many years in the use of the words investment and speculation.

Think of our suggested definition of investment given above, and compare it with the sale of a few shares of stock by an inexperienced member of the public, who does not even own what he is selling, and has some largely emotional conviction that he will be able to buy them back at a much lower price.

(It is not irrelevant to point out that when the 1962 article appeared the market had already experienced a decline of major size, and was now getting ready for an even greater upswing.

It was about as poor a time as possible for selling short.)

In a more general sense, the later-used phrase "reckless investors" could be regarded as a laughable contradiction in terms—something like "spendthrift misers"—were this misuse of language not so mischievous.

The newspaper employed the word "investor" in these instances because, in the easy language of Wall Street, everyone who buys or sells a security has become an investor, regardless of what he buys, or for what purpose, or at what price, or whether for cash or on margin.

Compare this with the attitude of the public toward common stocks in 1948, when over 90% of those queried expressed themselves as opposed to the purchase of common stocks.

About half gave as their reason "not safe, a gamble," and about half, the reason "not familiar with."

It is indeed ironical (though not surprising) that common-stock purchases of all kinds were quite generally regarded as highly speculative or risky at a time when they were selling on a most attractive basis, and due soon to begin their greatest advance in history; conversely the very fact they had advanced to what were undoubtedly dangerous levels as judged by past experience later transformed them into "investments," and the entire stock-buying public into "investors."

The distinction between investment and speculation in common stocks has always been a useful one and its disappearance is a cause for concern.

We have often said that Wall Street as an institution would be well advised to reinstate this distinction and to emphasize it in all its dealings with the public.

Otherwise the stock exchanges may some day be blamed for heavy speculative losses, which those who suffered them had not been properly warned against.

Ironically, once more, much of the recent financial embarrassment of some stock-exchange firms seems to have come from the inclusion of speculative common stocks in their own capital funds.

We trust that the reader of this book will gain a reasonably clear idea of the risks that are inherent in common-stock commitments—risks which are inseparable from the opportunities of profit that they offer, and both of which must be allowed for in the investor's calculations.

What we have just said indicates that there may no longer be such a thing as a simon-pure investment policy comprising representative common stocks—in the sense that one can always wait to buy them at a price that involves no risk of a market or "quotational" loss large enough to be disquieting.

In most periods the investor must recognize the existence of a speculative factor in his common-stock holdings.

It is his task to keep this component within minor limits, and to be prepared financially and psychologically for adverse results that may be of short or long duration.

Two paragraphs should be added about stock speculation per se, as distinguished from the speculative component now inherent in most representative common stocks.

Outright speculation is neither illegal, immoral, nor (for most people) fattening to the pocketbook.

More than that, some speculation is necessary and unavoidable, for in many common-stock situations there are substantial possibilities of both profit and loss, and the risks therein must be assumed by someone.

There is intelligent speculation as there is intelligent investing.

But there are many ways in which speculation may be unintelligent.

Of these the foremost are:

(1) speculating when you think you are investing;

(2) speculating seriously instead of as a pastime, when you lack proper knowledge and skill for it; and

(3) risking more money in speculation than you can afford to lose.

In our conservative view every nonprofessional who operates on margin should recognize that he is ipso facto speculating, and it is his broker's duty so to advise him.

And everyone who buys a so-called "hot" common-stock issue, or makes a purchase in any way similar thereto, is either speculating or gambling.

Speculation is always fascinating, and it can be a lot of fun while you are ahead of the game.

If you want to try your luck at it, put aside a portion—the smaller the better—of your capital in a separate fund for this purpose.

Never add more money to this account just because the market has gone up and profits are rolling in.

(That's the time to think of taking money out of your speculative fund.)

Never mingle your speculative and investment operations in the same account, nor in any part of your thinking.

Stock Selection for the Enterprising Investor

In the previous chapter we have dealt with common-stock selection in terms of broad groups of eligible securities, from which the defensive investor is free to make up any list that he or his adviser prefers, provided adequate diversification is achieved.

Our emphasis in selection has been chiefly on exclusions—advising on the one hand against all issues of recognizably poor quality, and on the other against the highest-quality issues if their price is so high as to involve a considerable speculative risk.

In this chapter, addressed to the enterprising investor, we must consider the possibilities and the means of making individual selections which are likely to prove more profitable than an across-the-board average.

What are the prospects of doing this successfully?

We would be less than frank, as the euphemism goes, if we did not at the outset express some grave reservations on this score.

At first blush the case for successful selection appears self-evident.

To get average results—e.g., equivalent to the performance of the DJIA—should require no special ability of any kind.

All that is needed is a portfolio identical with, or similar to, those thirty prominent issues.

Surely, then, by the exercise of even a moderate degree of skill—derived from study, experience, and native ability—it should be possible to obtain substantially better results than the DJIA.

Yet there is considerable and impressive evidence to the effect that this is very hard to do, even though the qualifications of those trying it are of the highest.

The evidence lies in the record of the numerous investment companies, or "funds," which have been in operation for many years.

Most of these funds are large enough to command the services of the best financial or security analysts in the field, together with all the other constituents of an adequate research department.

Their expenses of operation, when spread over their ample capital, average about one-half of 1% a year thereon, or less.

These costs are not negligible in themselves; but when they are compared with the approximately 15% annual overall return on common stocks generally in the decade 1951-1960, and even the 6% return in 1961-1970, they do not bulk large.

A small amount of superior selective ability should easily have overcome that expense handicap and brought in a superior net result for the fund shareholders.

Taken as a whole, however, the all-common-stock funds failed over a long span of years to earn quite as good a return as was shown on Standard & Poor's 500-stock averages or the market as a whole.

This conclusion has been substantiated by several comprehensive studies.

To quote the latest one before us, covering the period 1960-1968:

It appears from these results that random portfolios of New York Stock Exchange stocks with equal investment in each stock performed on the average better over the period than did mutual funds in the same risk class.

The differences were fairly substantial for the low- and medium-risk portfolios (3.7% and 2.5% respectively per annum), but quite small for the high-risk portfolios (0.2% per annum). 1

As we pointed out in Chapter 9, these comparative figures in no way invalidate the usefulness of the investment funds as a financial institution.

For they do make available to all members of the investing public the possibility of obtaining approximately average results on their common-stock commitments.

For a variety, of reasons, most members of the public who put their money in common stocks of their own choice fail to do nearly as well.

But to the objective observer the failure of the funds to better the performance of a broad average is a pretty conclusive indication that such an achievement, instead of being easy, is in fact extremely difficult.

Why should this be so?

We can think of two different explanations, each of which may be partially applicable.

The first is the possibility that the stock market does in fact reflect in the current prices not only all the important facts about the companies' past and current performance, but also whatever expectations can be reasonably formed as to their future.

If this is so, then the diverse market movements which subsequently take place—and these are often extreme—must be the result of new developments and probabilities that could not be reliably foreseen.

This would make the price movements essentially fortuitous and random.

To the extent that the foregoing is true, the work of the security analyst—however intelligent and thoroughmust be largely ineffective, because in essence he is trying to predict the unpredictable.

The very multiplication of the number of security analysts may have played an important part in bringing about this result.

With hundreds, even thousands, of experts studying the value factors behind an important common stock, it would be natural to expect that its current price would reflect pretty well the consensus of informed opinion on its value.

Those who would prefer it to other issues would do so for reasons of personal partiality or optimism that could just as well be wrong as right.

We have often thought of the analogy between the work of the host of security analysts in Wall Street and the performance of master bridge players at a duplicate-bridge tournament.

The former try to pick the stocks "most likely to succeed"; the latter to get top score for each hand played.

Only a limited few can accomplish either aim.

To the extent that all the bridge players have about the same level of expertness, the winners are likely to be determined by "breaks" of various sorts rather than superior skill.

In Wall Street the leveling process is helped along by the freemasonry that exists in the profession, under which ideas and discoveries are quite freely shared at the numerous get-togethers of various sorts.

It is almost as if, at the analogous bridge tournament, the various experts were looking over each other's shoulders and arguing out each hand as it was played.

The second possibility is of a quite different sort.

Perhaps many of the security analysts are handicapped by a flaw in their basic approach to the problem of stock selection.

They seek the industries with the best prospects of growth, and the companies in these industries with the best management and other advantages.

The implication is that they will buy into such industries and such companies at any price, however high, and they will avoid less promising industries and companies no matter how low the price of their shares.

This would be the only correct procedure if the earnings of the good companies were sure to grow at a rapid rate indefinitely in the future, for then in theory their value would be infinite.

And if the less promising companies were headed for extinction, with no salvage, the analysts would be right to consider them unattractive at any price.

The truth about our corporate ventures is quite otherwise.

Extremely few companies have been able to show a high rate of uninterrupted growth for long periods of time.

Remarkably few, also, of the larger companies suffer ultimate extinction.

For most, their history is one of vicissitudes, of ups and downs, of change in their relative standing.

In some the variations "from rags to riches and back" have been repeated on almost a cyclical basis—the phrase used to be a standard one applied to the steel industry—for others spectacular changes have been identified with deterioration or improvement of management.

Sidebar: From Management, Revised Edition: Preface by Peter Drucker

… But while the life expectancy of the individual and especially the individual knowledge worker has risen beyond anything anybody could have foretold at the beginning of the twentieth century, the life expectancy of the employing institution has been going down, and is likely to keep going down.

Or rather, the number of years has been shrinking during which an employing institution—and especially a business enterprise—can expect to stay successful.

This period was never very long.

Historically, very few businesses were successful for as long as thirty years in a row.

To be sure, not all businesses ceased to exist when they ceased to do well.

But the ones that survived beyond thirty years usually entered into a long period of stagnation—and only rarely did they turn around again and once more become successful growth businesses.

… snip, snip …

Thus, while the life expectancies and especially the working-life expectancies of the individual and especially of the knowledge worker have been expanding very rapidly, the life expectancy of the employing organizations has actually been going down.

And—in a period of very rapid technological change, of increasing competition because of globalization, of tremendous innovation—the successful life-expectancies of employing institutions are almost certain to continue to go down.

More and more people, and especially knowledge workers, can therefore expect to outlive their employing organizations and to have to be prepared to develop new careers, new skills, new social identities, new relationships, for the second half of their lives.

See Managing Oneself.

As an additional aside there is almost no (zero) overlap between the conceptual landscapes in Drucker and Graham's mental universes (although Drucker was a financial analyst early in his life)

… Now back to our story …

How does the foregoing inquiry apply to the enterprising investor who would like to make individual selections that will yield superior results?

It suggests first of all that he is taking on a difficult and perhaps impracticable assignment.

Readers of this book, however intelligent and knowing, could scarcely expect to do a better job of portfolio selection than the top analysts of the country.

But if it is true that a fairly large segment of the stock market is often discriminated against or entirely neglected in the standard analytical selections, then the intelligent investor may be in a position to profit from the resultant undervaluations.

But to do so he must follow specific methods that are not generally accepted in Wall Street, since those that are so accepted do not seem to produce the results everyone would like to achieve.

It would be rather strange if—with all the brains at work professionally in the stock market—there could be approaches which are both sound and relatively unpopular.

Yet our own career and reputation have been based on this unlikely fact.

1. Mutual Funds and Other Institutional Investors: A New Perspective, I. Friend, M. Blume, and J. Crockett, McGraw-Hill, 1970. We should add that the 1965-1970 results of many of the funds we studied were somewhat better than those of the Standard & Poor's 500-stock composite and considerably better than those of the DJIA.

Market Fluctuations of the Investor's Portfolio

Every investor who owns common stocks must expect to see them fluctuate in value over the years.

The behavior of the DJIA since our last edition was written in 1964 probably reflects pretty well what has happened to the stock portfolio of a conservative investor who limited his stock holdings to those of large, prominent, and conservatively financed corporations.

The overall value advanced from an average level of about 890 to a high of 995 in 1966 (and 985 again in 1968), fell to 631 in 1970, and made an almost full recovery to 940 in early 1971.

(Since the individual issues set their high and low marks at different times, the fluctuations in the Dow-Jones group as a whole are less severe than those in the separate components.)

We have traced through the price fluctuations of other types of diversified and conservative common-stock portfolios and we find that the overall results are not likely to be markedly different from the above.

In general, the shares of second-line companies fluctuate more widely than the major ones, but this does not necessarily mean that a group of well-established but smaller companies will make a poorer showing over a fairly long period.

In any case the investor may as well resign himself in advance to the probability rather than the mere possibility that most of his holdings will advance, say, 50% or more from their low point and decline the equivalent one-third or more from their high point at various periods in the next five years.

A serious investor is not likely to believe that the day-to-day or even month-to-month fluctuations of the stock market make him richer or poorer.

But what about the longer-term and wider changes?

Here practical questions present themselves, and the psychological problems are likely to grow complicated.

A substantial rise in the market is at once a legitimate reason for satisfaction and a cause for prudent concern, but it may also bring a strong temptation toward imprudent action.

Your shares have advanced, good! You are richer than you were, good! But has the price risen too high, and should you think of selling?

Or should you kick yourself for not having bought more shares when the level was lower?

Or—worst thought of all—should you now give way to the bull-market atmosphere, become infected with the enthusiasm, the overconfidence and the greed of the great public (of which, after all, you are a part), and make larger and dangerous commitments?

Presented thus in print, the answer to the last question is a self-evident no, but even the intelligent investor is likely to need considerable will power to keep from following the crowd.

It is for these reasons of human nature, even more than by calculation of financial gain or loss, that we favor some kind of mechanical method for varying the proportion of bonds to stocks in the investor's portfolio.

The chief advantage, perhaps, is that such a formula will give him something to do.

As the market advances he will from time to time make sales out of his stockholdings, putting the proceeds into bonds; as it declines he will reverse the procedure.

These activities will provide some outlet for his other wise too-pent-up energies.

If he is the right kind of investor he will take added satisfaction from the thought that his operations are exactly opposite from those of the crowd.

Business Valuations versus Stock-Market Valuations

The impact of market fluctuations upon the investor's true situation may be considered also from the standpoint of the stockholder as the part owner of various businesses.

The holder of marketable shares actually has a double status, and with it the privilege of taking advantage of either at his choice.

On the one hand his position is analogous to that of a minority stockholder or silent partner in a private business.

Here his results are entirely dependent on the profits of the enterprise or on a change in the underlying value of its assets.

He would usually determine the value of such a private business interest by calculating his share of the net worth as shown in the most recent balance sheet.

On the other hand, the common-stock investor holds a piece of paper, an engraved stock certificate, which can be sold in a matter of minutes at a price which varies from moment to moment—when the market is open, that is—and often is far removed from the balance-sheet value.

The development of the stock market in recent decades has made the typical investor more dependent on the course of price quotations and less free than formerly to consider himself merely a business owner.

The reason is that the successful enterprises in which he is likely to concentrate his holdings sell almost constantly at prices well above their net asset value (or book value, or "balance sheet value").

In paying these market premiums the investor gives precious hostages to fortune, for he must depend on the stock market itself to validate his commitments.

This is a factor of prime importance in present-day investing, and it has received less attention than it deserves.

The whole structure of stock-market quotations contains a built-in contradiction.

The better a company's record and prospects, the less relationship the price of its shares will have to their book value.

But the greater the premium above book value, the less certain the basis of determining its intrinsic value—i.e., the more this "value" will depend on the changing moods and measurements of the stock market.

Thus we reach the final paradox, that the more successful the company, the greater are likely to be the fluctuations in the price of its shares.

This really means that, in a very real sense, the better the quality of a common stock, the more speculative it is likely to be at least as compared with the unspectacular middle-grade issues.

(What we have said applies to a comparison of the leading growth companies with the bulk of well-established concerns; we exclude from our purview here those issues which are highly speculative because the businesses themselves are speculative.)

The argument made above should explain the often erratic price behavior of our most successful and impressive enterprises.

Our favorite example is the monarch of them all—International Business Machines.

The price of its shares fell from 607 to 300 in seven months in 1962-63; after two splits its price fell from 387 to 219 in 1970.

Similarly, Xerox—an even more impressive earnings gainer in recent decades—fell from 171 to 87 in 1962-63, and from 116 to 65 in 1970.

These striking losses did not indicate any doubt about the future long-term growth of IBM or Xerox; they reflected instead a lack of confidence in the premium valuation that the stock market itself had placed on these excellent prospects.

The previous discussion leads us to a conclusion of practical importance to the conservative investor in common stocks.

If he is to pay some special attention to the selection of his portfolio, it might be best for him to concentrate on issues selling at a reasonably close approximation their tangible-asset value—say, at not more than one-third above that figure.

Purchases made at such levels, or lower, may with logic be regarded as related to the company's balance sheet, and as having a justification or support independent of the fluctuating market prices.

The premium over book value that may be involved can be considered as a kind of extra fee paid for the advantage of stock-exchange listing and the marketability that goes with it.

A caution is needed here.

A stock does not become a sound investment merely because it can be bought close to its asset value.

The investor should demand, in addition, a satisfactory ratio of earnings to price, a sufficiently strong financial position, and the prospect that its earnings will at least be maintained over the years.

This may appear like demanding a lot from a modestly priced stock, but the prescription is not hard to fill under all but dangerously high market conditions.

Once the investor is willing to forgo brilliant prospects—i.e., better than average expected growth—he will have no difficulty in finding a wide selection of issues meeting these criteria.

In our chapters on the selection of common stocks (Chapters 14 and 15) we shall give data showing that more than half of the DJIA issues met our asset-value criterion at the end of 1970.

The most widely held investment of all—American Tel. & Tel.—actually sells below its tangible-asset value as we write.

Most of the light-and-power shares, in addition to their other advantages, are now (early 1972) available at prices reasonably close to their asset values.

The investor with a stock portfolio having such book values behind it can take a much more independent and detached view of stock-market fluctuations than those who have paid high multipliers of both earnings and tangible assets.

As long as the earning power of his holdings remains satisfactory, he can give as little attention as he pleases to the vagaries of the stock market.

More than that, at times he can use these vagaries to play the master game of buying low and selling high.

The A. & P. Example

At this point we shall introduce one of our original examples, which dates back many years but which has a certain fascination for us because it combines so many aspects of corporate and investment experience.

It involves the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. Here is the story:

A. & P. shares were introduced to trading on the "Curb" market, now the American Stock Exchange, in 1929 and sold as high as 494.

By 1932 they had declined to 104, although the company's earnings were nearly as large in that generally catastrophic year as previously.

In 1936 the range was between 111 and 131.

Then in the business recession and bear market of 1938 the shares fell to a new low of 36.

That price was extraordinary.

It meant that the preferred and common were together selling for $126 million, although the company had just reported that it held $85 million in cash alone and a working capital (or net current assets) of $134 million.

A. & P. was the largest retail enterprise in America, if not in the world, with a continuous and impressive record of large earnings for many years.

Yet in 1938 this outstanding business was considered in Wall Street to be worth less than its current assets alone—which means less as a going concern than if it were liquidated.

Why?

First, because there were threats of special taxes on chain stores; second, because net profits had fallen off in the previous year; and, third, because the general market was depressed.

The first of these reasons was an exaggerated and eventually groundless fear; the other two were typical of temporary influences.

Let us assume that the investor had bought A. & P. common in 1937 at, say, 12 times its five-year average earnings, or about 80.

We are far from asserting that the ensuing decline to 36 was of no importance to him.

He would have been well advised to scrutinize the picture with some care, to see whether he had made any miscalculations.

But if the results of his study were reassuring—as they should have been—he was entitled then to disregard the market decline as a temporary vagary of finance, unless he had the funds and the courage to take advantage of it by buying more on the bargain basis offered.

Sequel and Reflections

The following year, 1939, A. & P. shares advanced to 117 ½, or three times the low price of 1938 and well above the average of 1937. Such a turnabout in the behavior of common stocks is by no means uncommon, but in the case of A. & P. it was more striking than most.

In the years after 1949 the grocery chain's shares rose with the general market until in 1961 the split-up stock (10 for 1) reached a high of 70 ½ which was equivalent to 705 for the 1938 shares.

This price of 70 ½ was remarkable for the fact it was 30 times the earnings of 1961.

Such a price/earnings ratio—which compares with 23 times for the DJIA in that year—must have implied expectations of a brilliant growth in earnings.

This optimism had no justification in the company's earnings record in the preceding years, and it proved completely wrong.

Instead of advancing rapidly, the course of earnings in the ensuing period was generally downward.

The year after the 70 ½ high the price fell by more than half to 34.

But this time the shares did not have the bargain quality that they showed at the low quotation in 1938.

After varying sorts of fluctuations the price fell to another low of 21 ½ in 1970 and 18 in 1972—having reported the first quarterly deficit in its history.

We see in this history how wide can be the vicissitudes of a major American enterprise in little more than a single generation, and also with what miscalculations and excesses of optimism and pessimism the public has valued its shares.

In 1938 the business was really being given away, with no takers; in 1961 the public was clamoring for the shares at a ridiculously high price.

After that came a quick loss of half the market value, and some years later a substantial further decline.

In the meantime the company was to turn from an outstanding to a mediocre earnings performer; its profit in the boom-year 1968 was to be less than in 1958; it had paid a series of confusing small stock dividends not warranted by the current additions to surplus; and so forth.

A. & P. was a larger company in 1961 and 1972 than in 1938, but not as well-run, not as profitable, and not as attractive.

There are two chief morals to this story.

The first is that the stock market often goes far wrong, and sometimes an alert and courageous investor can take advantage of its patent errors.

The other is that most businesses change in character and quality over the years, sometimes for the better, perhaps more often for the worse.

The investor need not watch his companies' performance like a hawk; but he should give it a good, hard look from time to time.

Let us return to our comparison between the holder of marketable shares and the man with an interest in a private business.

We have said that the former has the option of considering himself merely as the part owner of the various businesses he has invested in, or as the holder of shares which are salable at any time he wishes at their quoted market price.

But note this important fact: The true investor scarcely ever is forced to sell his shares, and at all other times he is free to disregard the current price quotation.

He need pay attention to it and act upon it only to the extent that it suits his book, and no more.

Thus the investor who permits himself to be stampeded or unduly worried by unjustified market declines in his holdings is perversely transforming his basic advantage into a basic disadvantage.

That man would be better off if his stocks had no market quotation at all, for he would then be spared the mental anguish caused him by other persons' mistakes of judgment.

Incidentally, a widespread situation of this kind actually existed during the dark depression days of 1931-1933.

There was then a psychological advantage in owning business interests that had no quoted market.

For example, people who owned first mortgages on real estate that continued to pay interest were able to tell themselves that their investments had kept their full value, there being no market quotations to indicate otherwise.

On the other hand, many listed corporation bonds of even better quality and greater underlying strength suffered severe shrinkages in their market quotations, thus making their owners believe they were growing distinctly poorer.

In reality the owners were better off with the listed securities, despite the low prices of these.

For if they had wanted to, or were compelled to, they could at least have sold the issues—possibly to exchange them for even better bargains.

Or they could just as logically have ignored the market's action as temporary and basically meaningless.

But it is self-deception to tell yourself that you have suffered no shrinkage in value merely because your securities have no quoted market at all.

Returning to our A. & P. stock-holder in 1938, we assert that as long as he held on to his shares he suffered no loss in their price decline, beyond what his own judgment may have told him was occasioned by a shrinkage in their underlying or intrinsic value.

If no such shrinkage had occurred, he had a right to expect that in due course the market quotation would return to the 1937 level or better—as in fact it did the following year.

In this respect his position was at least as good as if he had owned an interest in a private business with no quoted market for its shares.

For in that case, too, he might or might not have been justified in mentally lopping off part of the cost of his holdings because of the impact of the 1938 recession—depending on what had happened to his company.

Critics of the value approach to stock investment argue that listed common stocks cannot properly be regarded or appraised in the same way as an interest in a similar private enterprise, because the presence of an organized security market "injects" into equity ownership the new and extremely important attribute of liquidity."

But what this liquidity really means is, first, that the investor has the benefit of the stock market's daily and changing appraisal of his holdings, for whatever that appraisal may be worth, and, second, that the investor is able to increase or decrease his investment at the market's daily figure—if he chooses.

Thus the existence of a quoted market gives the investor certain options that he does not have if his security is unquoted.

But it does not impose the current quotation on an investor who prefers to take his idea of value from some other source.

Mr. Market

Let us close this section with something in the nature of a parable.

Imagine that in some private business you own a small share that cost you $1,000.

One of your partners, named Mr. Market, is very obliging indeed.

Every day he tells you what he thinks your interest is worth and furthermore offers either to buy you out or to sell you an additional interest on that basis.

Sometimes his idea of value appears plausible and justified by business developments and prospects as you know them.

Often, on the other hand, Mr. Market lets his enthusiasm or his fears run away with him, and the value he proposes seems to you a little short of silly.

If you are a prudent investor or a sensible businessman, will you let Mr. Market's daily communication determine your view of the value of a $1,000 interest in the enterprise?

Only in case you agree with him, or in case you want to trade with him.

You may be happy to sell out to him when he quotes you a ridiculously high price, and equally happy to buy from him when his price is low.

But the rest of the time you will be wiser to form your own ideas of the value of your holdings, based on full reports from the company about its operations and financial position.

The true investor is in that very position when he owns a listed common stock.

He can take advantage of the daily market price or leave it alone, as dictated by his own judgment and inclination.

He must take cognizance of important price movements, for otherwise his judgment will have nothing to work on.

Conceivably they may give him a warning signal which he will do well to heed—this in plain English means that he is to sell his shares because the price has gone down, foreboding worse things to come.

In our view such signals are misleading at least as often as they are helpful.

Basically, price fluctuations have only one significant meaning for the true investor.

They provide him with an opportunity to buy wisely when prices fall sharply and to sell wisely when they advance a great deal.

At other times he will do better if he forgets about the stock market and pays attention to his dividend returns and to the operating results of his companies (calendarize this).

Summary

The most realistic distinction between the investor and the speculator is found in their attitude toward stock-market movements.

The speculator's primary interest lies in anticipating and profiting from market fluctuations.

The investor's primary interest lies in acquiring and holding suitable securities at suitable prices.

Market movements are important to him in a practical sense, because they alternately create low price levels at which he would be wise to buy and high price levels at which he certainly should refrain from buying and probably would be wise to sell.

It is far from certain that the typical investor should regularly hold off buying until low market levels appear, because this may involve a long wait, very likely the loss of income, and the possible missing of investment opportunities.

On the whole it may be better for the investor to do his stock buying whenever he has money to put in stocks, except when the general market level is much higher than can be justified by well-established standards of value.

If he wants to be shrewd he can look for the ever-present bargain opportunities in individual securities.

Aside from forecasting the movements of the general market, much effort and ability are directed in Wall Street toward selecting stocks or industrial groups that in matter of price will "do better" than the rest over a fairly short period in the future.

Logical as this endeavor may seem, we do not believe it is suited to the needs or temperament of the true investor—particularly since he would be competing with a large number of stock-market traders and first-class financial analysts who are trying to do the same thing.

As in all other activities that emphasize price movements first and underlying values second, the work of many intelligent minds constantly engaged in this field tends to be self-neutralizing and self-defeating over the years.

The investor with a portfolio of sound stocks should expect their prices to fluctuate and should neither be concerned by sizable declines nor become excited by sizable advances.

He should always remember that market quotations are there for his convenience, either to be taken advantage of or to be ignored.

He should never buy a stock because it has gone up or sell one because it has gone down.

He would not be far wrong if this motto read more simply: "Never buy a stock immediately after a substantial rise or sell one immediately after a substantial drop."

An Added Consideration

Something should be said about the significance of average market prices as a measure of managerial competence.

The stockholder judges whether his own investment has been successful in terms both of dividends received and of the long-range trend of the average market value.

The same criteria should logically be applied in testing the effectiveness of a company's management and the soundness of its attitude toward the owners of the business.

This statement may sound like a truism, but it needs to be emphasized.

For as yet there is no accepted technique or approach by which management is brought to the bar of market opinion.

On the contrary, managements have always insisted that they have no responsibility of any kind for what happens to the market value of their shares.

It is true, of course, that they are not accountable for those fluctuations in price which, as we have been insisting, bear no relationship to underlying conditions and values.

But it is only the lack of alertness and intelligence among the rank and file of stockholders that permits this immunity to extend to the entire realm of market quotations, including the permanent establishment of a depreciated and unsatisfactory price level.

Good managements produce a good average market price, and bad managements produce bad market prices.

Fluctuations in Bond Prices

The investor should be aware that even though safety of its principal and interest may be unquestioned, a long-term bond could vary widely in market price in response to changes in interest rates.

In Table 8-1 we give data for various years back to 1902 covering yields for high-grade corporate and tax-free issues.

As individual illustrations we add the price fluctuations of two representative railroad issues for a similar period.

(These are the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe general mortgage 4s, due 1995, for generations one of our premier noncallable bond issues, and the Northern Pacific Ry.

3s, due 2047—originally a 150 year maturity! —long a typical Baa-rated bond.)

Because of their inverse relationship the low yields correspond to the high prices and vice versa.

The decline in the Northern Pacific 3s in 1940 represented mainly doubts as to the safety of the issue.

It is extraordinary that the price recovered to an all-time high in the next few years, and then lost two-thirds of its price chiefly because of the rise in general interest rates.

There have been startling variations, as well, in the price of even the highest-grade bonds in the past forty years.

Note that bond prices do not fluctuate in the same (inverse) proportion as the calculated yields, because their fixed maturity value of 100% exerts a moderating influence.

However, for very long maturities, as in our Northern Pacific example, prices and yields change at close to the same rate.

Since 1964 record movements in both directions have taken place in the high-grade bond market.

Taking "prime municipals" (tax-free) as an example, their yield more than doubled, from 3.2% in January 1965 to 7% in June 1970.

Their price index declined, correspondingly, from 110.8 to 67.5.

In mid-1970 the yields on high-grade long-term bonds were higher than at any time in the nearly 200 years of this country's economic history.

Twenty-five years earlier, just before our protracted bull market began, bond yields were at their lowest point in history; long-term municipals returned as little as 1%, and industrials gave 2.40% compared with the 4 ½ % to 5% formerly considered "normal."

Those of us with a long experience in Wall Street had seen Newton's law of "action and reaction, equal and opposite" work itself out repeatedly in the stock market—the most noteworthy example being the rise in the DJIA from 64 in 1921 to 381 in 1929, followed by a record collapse to 41 in 1932.

But this time the widest pendulum swings took place in the usually staid and slow-moving array of high-grade bond prices and yields.

Moral: Nothing important in Wall Street can be counted on to occur exactly in the same way as it happened before.

This represents the first half of our favorite dictum: "The more it changes, the more it's the same thing."

If it is virtually impossible to make worthwhile predictions about the price movements of stocks, it is completely impossible to do so for bonds.

In the old days, at least, one could often find a useful clue to the coming end of a bull or bear market by studying the prior action of bonds, but no similar clues were given to a coming change in interest rates and bond prices.

Hence the investor must choose between long-term and short-term bond investments on the basis chiefly of his personal preferences.

If he wants to be certain that the market values will not decrease, his best choices are probably U.S. savings bonds, Series E or H, which were described above, p. 45.

Either issue will give him a 5% yield (after the first year), the Series E for up to 5/6 years, the Series H for up to ten years, with a guaranteed resale value of cost or better.

If the investor wants the 7.5% now available on good long-term corporate bonds, or the 5.3% on tax-free municipals, he must be prepared to see them fluctuate in price.

Banks and insurance companies have the privilege of valuing high-rated bonds of this type on the mathematical basis of "amortized" which disregards market prices; it would not be a bad idea for the individual investor to do something similar.

The price fluctuations of convertible bonds and preferred stocks are the resultant of three different factors: (1) variations in the price of the related common stock, (2) variations in the credit standing of the company, and (3) variations in general interest rates.

A good many of the convertible issues have been sold by companies that have credit ratings well below the best. 3

Some of these were badly affected by the financial squeeze in 1970.

As a result, convertible issues as a whole have been subjected to triply unsettling influences in recent years, and price variations have been unusually wide.

In the typical case, therefore, the investor would delude himself if he expected to find in convertible issues that ideal combination of the safety of a high-grade bond and price protection plus a chance to benefit from an advance in the price of the common.

This may be a good place to make a suggestion about the "long-term bond of the future."

Why should not the effects of changing interest rates be divided on some practical and equitable basis between the borrower and the lender?

One possibility would be to sell long-term bonds with interest payments that vary with an appropriate index of the going rate.

The main results of such an arrangement would be: (1) the investor's bond would always have a principal value of about 100, if the company maintains its credit rating, but the interest received will vary, say, with the rate offered on conventional new issues; (2) the corporation would have the advantages of long-term debt—being spared problems and costs of frequent renewals or refinancing—but its interest costs would change from year to year. 4

Over the past decade the bond investor has been confronted by an increasingly serious dilemma: Shall he choose complete stability of principal value, but with varying and usually low (short-term) interest rates?

Or shall he choose a fixed-interest income, with considerable variations (usually downward, it seems) in his principal value?

It would be good for most investors if they could compromise between these extremes, and be assured that neither their interest return nor their principal value will fall below a stated minimum over, say, a 20-year period.

This could be arranged, without great difficulty, in an appropriate bond contract of a new form.

Important note: In effect the U.S. government has done a similar thing in its combination of the original savings-bonds contracts with their extensions at higher interest rates.

The suggestion we make here would cover a longer fixed investment period than the savings bonds, and would introduce more flexibility in the interest rate provisions.

It is hardly worthwhile to talk about nonconvertible preferred stocks, since their special tax status makes the safe ones much more desirable holdings by corporations—e.g., insurance companies than by individuals.

The poorer-quality ones almost always fluctuate over a wide range, percentage wise, not too differently from common stocks.

We can offer no other useful remark about them.

Table 16-2 below, p.

222, gives some information on the price changes of lower-grade nonconvertible preferreds between December 1968 and December 1970.

The average decline was 17%, against 11.3% for the S & P composite index of common stocks.

3.

The top three ratings for bonds and preferred stocks are Aaa, Aa, and A, used by Moody's, and AAA, AA, A by Standard & Poor's.

There are others, going down to D.

4.

This idea has already had some adoptions in Europe—e.g., by the state-owned Italian electric energy concern on its "guaranteed floating rate loan notes," due 1980.

In June 1971 it advertised in New York that the annual rate of interest paid thereon for the next six months would be 8 ½ %.

One such flexible arrangement was incorporated in The Toronto-Dominion Bank's "7%-8% debentures," due 1991, offered in June 1971.

The bonds pay 7% to July 1976 and 8% thereafter, but the holder has the option to receive his principal in July 1976.

Industry Analysis

Because the general prospects of the enterprise carry major weight in the establishment of market prices, it is natural for the security analyst to devote a great deal of attention to the economic position of the industry and of the individual company in its industry.

Studies of this kind can go into unlimited detail.

They are sometimes productive of valuable insights into important factors that will be operative in the future and are insufficiently appreciated by the current market.

Where a conclusion of that kind can be drawn with a fair degree of confidence, it affords a sound basis for investment decisions.

Our own observation, however, leads us to minimize somewhat the practical value of most of the industry studies that are made available to investors.

The material developed is ordinarily of a kind with which the public is already fairly familiar and that has already exerted considerable influence on market quotations.

Rarely does one find a brokerage-house study that points out, with a convincing array of facts, that a popular industry is heading for a fall or that an unpopular one is due to prosper.

Wall Street's view of the longer future is notoriously fallible, and this necessarily applies to that important part of its investigations which is directed toward the forecasting of the course of profits in various industries.

We must recognize, however, that the rapid and pervasive growth of technology in recent years is not without major effect on the attitude and the labors of the security analyst.

More so than in the past, the progress or retrogression of the typical company in the coming decade may depend on its relation to new products and new processes, which the analyst may have a chance to study and evaluate in advance.

Thus there is doubtless a promising area for effective work by the analyst, based on field trips, interviews with research men, and on intensive technological investigation on his own.

There are hazards connected with investment conclusions derived chiefly from such glimpses into the future, and not supported by presently demonstrable value.

Yet there are perhaps equal hazards in sticking closely to the limits of value set by sober calculations resting on actual results.

The investor cannot have it both ways.

He can be imaginative and play for the big profits that are the reward for vision proved sound by the event; but then he must run a substantial risk of major or minor miscalculation.

Or he can be conservative, and refuse to pay more than a minor premium for possibilities as yet unproved; but in that case he must be prepared for the later contemplation of golden opportunities foregone.

See Warren Buffett

TLN keywords: tlnkwintelligentinvestorquotes

|

![]()