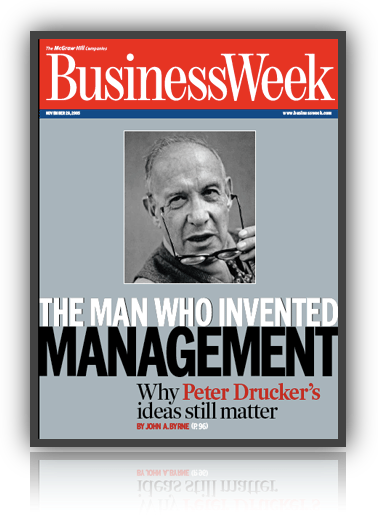

The Frontiers of Management

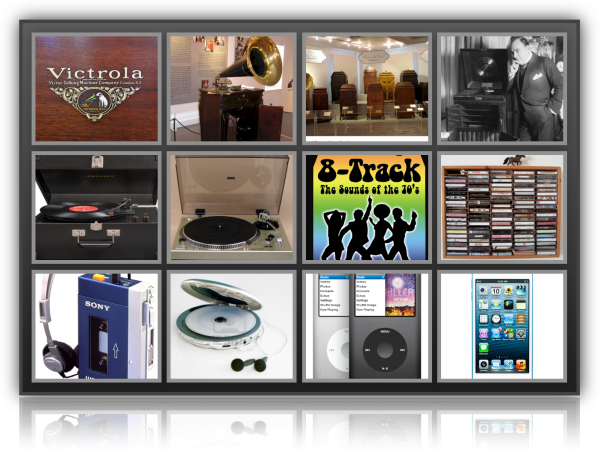

by Peter Drucker — his other books

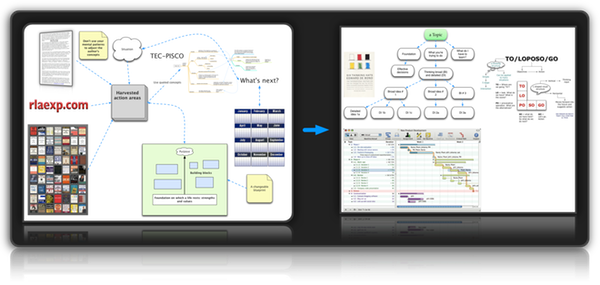

See rlaexp.com initial bread-crumb trail — toward the

end of this page — for a site “overview”

Amazon link: The Frontiers of Management: Where Tomorrow's Decisions Are Being Shaped Today (Drucker Library)

See about management

- Frontiers of management

- The Future is Being Shaped Today

- Interview

- Economics

- The Changed World Economy

- America's Entrepreneurial Job Machine

- Why OPEC Had to Fail

- The Changing Multinational

- Managing Currency Exposure

- Export Markets and Domestic Policies

- Europe's High-Tech Ambitions

- What We Can Learn from the Germans

- On Entering the Japanese Market

- Trade with Japan: The Way It Works

- The Perils of Adversarial Trade

- Modern Prophets: Schumpeter or Keynes?

- People

- Picking People: The Basic Rules

- Measuring White Collar Productivity

- Twilight of the first-Line Supervisor?

- Overpaid Executives: The Greed Effect

- Overage Executives: Keeping Firms Young

- Paying the Professional Schools

- Jobs and People: The Growing Mismatch

- Quality Education: The New Growth Area

- Management

- The Organization

- Social Innovation—Management's New Dimension

- Priorities

Preface: The Future Is Being Shaped Today

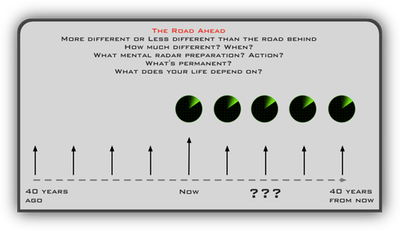

To predict the future is futile.

But to look searchingly at new and unexpected developments in the present and to ask what might they foretell is the way to prepare for the future.

And this is what The Frontiers of Management—and every chapter in this volume—tried to do.

Many, many years ago, when I was a green beginner, a wise old editor said to me: “You’ll never make a first-rate journalist; you always think of next month instead of next morning.”

He was right do not look at a “story” as tomorrow’s headline.

I rather look at it as the harbinger of headlines a year or two hence.

There is risk in this—so many of the sensations of today are only tomorrow’s tired fads.

But one can learn to distinguish between the two.

There are a few—a very few—events of today which first indicate important and long-run changes, first sound a new note, first signal new issues.

It is on these that a successful business policy and a successful business strategy have to be based.

I have divided my writings for many years into two categories.

There are the big books—most of them quite a few years in the making.

They present one major subject in depth and are written to be the definitive text on a major area, if not to found a new discipline.

My 1954 book, The Practice of Management, for instance, is still being used all over the world as both the basic introduction to the subject for management student and beginner, and as a reference work for the experienced manager and executive.

And then there are essays and articles—such as those assembled in this volume—which analyze today’s events in order to reach out, to anticipate, to divine tomorrow’s new opportunities and tomorrow’s new challenges.

They are, so to speak, “reconnaissances in force.”

Frontiers of Management presents five years of such “reconnaissance” essays and articles, written between 1982 and 1986.

The book was actually planned all along—from the day in 1982 when the first of the essays was written—to bring together in one volume the best and most durable of these analyses of then current events likely to become tomorrow’s big issues.

It has lived up to this ambition.

For this book—now more than ten years old—continues still to be in so much demand that the publisher has decided to bring it out in this new paperback edition.

It is an unrevised edition—purposefully so; not one word of the original has been changed.

Readers can therefore decide for themselves where the author got it wrong.

The only change is the addition of this new introduction to the book.

It comments on the essays in each part from the vantage point of 1997.

I trust and hope that readers will find that these essays—precisely because they were written when a topic first emerged—tell them as much about crucial issues of 1997 or 2000 as some of the voluminous treatises now being written about these topics.

Above all I hope that this republication of Frontiers of Management will induce readers to ask the right questions.

Interview: A Talk With A Wide-Ranging Mind

Q: The last book of yours was the one in which you wrote about the deliberateness of the innovation process. Has there been any deliberateness in your own life? Was there a plan for Peter Drucker?

A: In retrospect, my life makes sense, but not in prospect, no.

I was probably thirty before I had the foggiest notion where I belonged.

For ten or twelve years before that I had experimented, not by design but by accident.

I knew, even as a little boy, that I didn’t want to stay in Austria, and I knew that I didn’t want to waste four years going to a university.

So I had my father get me a job as far away as one could go and as far away from anything that I was eventually headed for.

I was an apprentice clerk in an export house.

Then I worked in a small bank in Frankfurt.

It’s a job I got because I was bilingual in English and German.

That was October 1929.

The stock market crashed, and I was the last in and the first out.

I needed a job and got one at the local newspaper.

It was a good education, I must say.

In retrospect, the one thing I was good at was looking at phenomena and asking what they meant.

I knew in 1933 how Hitler would end, and I then began my first book, The End of Economic Man, which could not be published until 1939, because no publisher was willing to accept such horrible insights.

It was very clear to me that Hitler would end up killing the Jews.

And it was also very clear that he would end up with a treaty with Stalin.

I had been quite active in German conservative politics even though I had a foreign passport, and so I knew that Hitler was not for me.

I left and went first to England and then, four years later, to this country.

I worked in London for an insurance company as a securities analyst and as an investment banker.

If I had wanted to be a rich man I would have stayed there, but it bored me to tears.

Q: Would you define entrepreneur?

A: The definition is very old.

It is somebody who endows resources with new wealth-producing capacity.

That’s all.

(But not in the way you’d expect. Get a Kindle version of Management, Revised Edition and do a key word search on entrepreneur then entrepreneurship. — bobembry)

Q: You make the point that small business and entrepreneurial business are not necessarily the same thing.

A: The great majority of small businesses are incapable of innovation, partly because they don’t have the resources, but a lot more because they don’t have the time and they don’t have the ambition.

I’m not even talking of the corner cigar store.

Look at the typical small business.

It’s grotesquely understaffed.

It doesn’t have the resources and the cash flow.

Maybe the boss doesn’t sweep the store anymore, but he’s not that far away.

He’s basically fighting the daily battle.

He doesn’t have, by and large, the discipline.

He doesn’t have the background.

The most successful of the young entrepreneurs today are people who have spent five to eight years in a big organization.

Q: What does that do for them?

A: They learn.

They get tools.

They learn how to do a cash-flow analysis and how one trains people and how one delegates and how one builds a team.

The ones without that background are the entrepreneurs who, no matter how great their success, are being pushed out.

For example, if you ask me what’s wrong with [Apple Computer Inc. cofounders] Wozniak and Jobs .

Q: That’s exactly what I was going to ask

A: They don’t have the discipline.

They don’t have the tools, the knowledge.

Q: But that’s the company that we’ve looked to for the past five or six years as being prototypical of entrepreneurial success.

A: I am on record as saying that those two young men would not survive.

The Lord was singularly unkind to them.

Q: Really?

A: By giving them too much success too soon.

If the Lord wants to destroy, He does what He did to those two.

They never got their noses rubbed in the dirt.

They never had to dig.

It came too easy.

Success made them arrogant.

They don’t know the simple elements.

They’re like an architect who doesn’t know how one drives a nail or what a stud is.

A great strength is to have five to ten years of, call it management, under your belt before you start.

If you don’t have it, then you make these elementary mistakes.

Q: People who haven’t had this big-company experience you prescribe: would you tell them that they shouldn’t attempt their own enterprise?

A: No, I would say read my entrepreneurial book, because that’s what it’s written for.

We have reached the point [in entrepreneurial management] where we know what the practice is, and it’s not waiting around for the muse to kiss you.

The muse is very, very choosy, not only in whom she kisses but in where she kisses them.

And so one can’t wait.

In high tech, we have the old casualty rate among young companies, eight out of ten, or seven out of ten. But outside of high tech, the rate is so much lower.

Q: Because?

A: Because they have the competence to manage their enterprises and to manage themselves.

That’s the most difficult thing for the person who starts his own business, to redefine his own role in the business.

Q: You make it sound so easy in the book

A: It is simple, but not easy.

What you have to do and how you do it are incredibly simple.

Are you willing to do it?

That is another matter.

You have to ask the question.

There is a young man I know who starts businesses.

He is on his fifth.

He develops them to the point that they are past the baby diseases and then sells out.

He’s a nanny.

You know, when I grew up there were still nannies around, and most of them used to give notice on the day their child spoke its first word.

Then it was no longer a baby.

That’s what this particular fellow is, a baby nurse.

When his companies reach twenty-nine employees he says, “Out!” I ask why and he says, “Once I get to thirty people, including myself, then I have to manage them, and I’m simply not going to do anything that stupid.”

Q: That example would tend to confirm the conventional wisdom, which holds that there are entrepreneurs and there are managers, but that the two are not the same.

A: Yes and no.

You see, there is entrepreneurial work and there is managerial work, and the two are not the same.

But you can’t be a successful entrepreneur unless you manage, and if you try to manage without some entrepreneurship, you are in danger of becoming a bureaucrat.

Yes, the work is different, but that’s not so unusual.

Look at entrepreneurial businesses today.

A lot of them are built around somebody in his fifties who came straight out of college, engineering school, and went to work for GE.

Thirty years later, he is in charge of market research for the small condenser department and is very nicely paid.

His mortgage is paid up and his pension is vested, the kids are grown, and he enjoys the work and likes GE, but he knows he’s never going to be general manager of the department, let alone of the division.

And that’s when he takes early retirement, and three weeks later, he’s working for one of the companies around Route 128 in Boston.

This morning I talked to one of those men.

He had been in market planning and market research for a du Pont division—specialty chemicals—and he said, “You know, I was in my early fifties, and I enjoyed it, but they wanted to transfer me.

Do I have to finish the story?

So now he’s a vice-president for marketing on Route 128 in a company where he is badly needed, an eight-year-old company of engineers that has grown very fast and has outgrown its marketing.

But he knows how one does it.

At du Pont, was he an entrepreneur or was he a manager?

He knows more about how one finds new markets than the boys at his new company do.

He’s been doing it for thirty years.

It’s routine.

You come out with something, and it works fine in the market, but then you see what other markets there are that you never heard of.

There are lots of markets that have nothing to do with the treatment of effluents, or whatever that company does, but they didn’t know how to find them until this fellow came along.

There is entrepreneurial work and there is managerial work, and most people can do both.

But not everybody is attracted to them equally.

The young man I told you about who starts companies, he asked himself the question, and his answer was, “I don’t want to run a business.”

Q: Isn’t there some irony in the fact that you who study organizations aren’t part of one?

A: I couldn’t work in a large organization. They bore me to tears.

Q: Aren’t you being very hard on the Route 128 and Silicon Valley people? You’ve called them arrogant, immature.

A: High tech is living in the nineteenth century, the pre-management world.

They believe that people pay for technology.

They have a romance with technology.

But people don’t pay for technology: they pay for what they get out of technology.

If you look at the successful companies, they are the ones who either learn management or bring it in.

In the really successful high-tech companies, the originator isn’t usually there five years later.

He may be on the board; he may be honorary chairman; but he is out, and usually with bitterness.

The Apple story is different only in its dimensions.

Steve Jobs lacked the discipline.

I don’t mean the self-discipline.

I mean the basic knowledge and the willingness to apply it.

High tech, precisely because it has all the glamour, is prone to arrogance far more than any other.

But it’s not confined to high tech.

Q: Where else?

A: Finance.

There’s a different kind of egomaniac there, but still an egomaniac.

Partly for the same reason.

They make too much money too soon.

It spoils you, you know, to get $450,000 in stock options at age twenty-three.

It’s a very dangerous thing.

It’s too much excitement.

Q: This entrepreneurial society that you write about in the book, how did it develop? And are you absolutely persuaded that it’s not just a fad?

A: Certainly, demographics have had a lot to do with it.

You go back thirty years, twenty-five years, and the able graduates of, let’s say, Harvard Business School all wanted to go into big business.

And it was a rational, intelligent thing to do because the career opportunities were there.

But now, you see, because of the baby boom, the pipelines are full.

Another reason we have an entrepreneurial society, and it’s an important reason, is that high tech has made it respectable.

The great role of high tech is in creating the climate for entrepreneurs, the vision.

And it has also created the sources of capital.

When you go to the venture capitalists, you know, most of them are no longer emphasizing high tech.

But all of them began in high tech.

It was high tech that created the capital flow.

And how recent this is is very hard to imagine.

In 1976, I published a book on pension funds in which I said that one of the great problems in making capital formation institutional is that there won’t be any money for new businesses.

That was only ten years ago and at that time what I said was obvious.

Today it would be silly.

The third thing promoting the entrepreneurial society perhaps is the most important, although I’m not sure whether I’m talking chicken or egg.

There’s been a fundamental change in basic perception over the past, make it, fifty years.

The trend was toward centralization—in business, in government, and in health care.

At the same time, when we came out of World War II we had discovered management.

But management was something that we thought could work only in large, centralized institutions.

In the early 1950s, I helped start what became the Presidents’ Course given by the American Management Associations.

In the first years, until 1970, for every hundred people they invited, eighty wrote back and said: “This is very interesting, but I’m not GE.

What would I need management for?”

And the same was true when I first started to work with the American College of Hospital Administrators, which gave a seminar in management.

Hospital administrators needed it, but invariably we got the answer, “We have only ninety beds; we can’t afford management.”

This has all changed now.

Don’t ask me how and when.

But nowadays, the only place left where you still have the cult of bigness is in Japan.

There, bigger is better and biggest is best.

So, in part, the entrepreneurial society came about because we all “learned” how to manage.

It’s become part of the general culture.

Look, Harper & Row—who is the publisher for [Tom] Peters and [Bob] Waterman—half of the 2 or 3 million books they sold were graduation presents for high school graduates.

Q: Your book or In Search of Excellence?

A: Oh, no, no.

Not my book.

My book would be hopeless.

They couldn’t read it, much less master it.

The great virtue of the Peters and Waterman book is its extreme simplicity, maybe oversimplification.

But when Aunt Mary has to give that nephew of hers a high school graduation present and she gives him In Search of Excellence, you know that management has become part of the general culture.

Q: Does the arrival of the entrepreneurial society mean that we should be rejoicing now because our national economic future is assured?

A: No. It’s bringing tremendous change to a lot of vast institutions, and if they can’t learn, the changes will be socially unbearable.

Q: Has any of them started to change?

A: My God, yes.

The new companies are the least of it, historically.

The more important part is what goes on in existing institutions.

What is far more important is that the American railroad has become innovative with a vengeance in the last thirty years.

When I first knew the railroads in the late 1940s, there was no hope for them.

I was quite sure that they would all have to be nationalized.

Now, even Conrail, the government-owned railroad, makes money.

What has happened in finance is even more dramatic.

In, make it, 1960, some smart cookies at General Electric Credit Corporation realized that commercial paper is a commercial loan, not legally, but economically.

Legally, in this country, it’s a security, so the commercial banks have a hard time using it.

Our number-two bank is not Chase and not Bank of America.

It’s General Electric Credit.

The most robotized plant in the world is probably the GE locomotive plant in Erie, Pennsylvania.

Twenty years ago, GE didn’t make a single locomotive in this country.

It was much too expensive.

They were all made by GE Brazil.

Now, the U.S. plant is far more automated than anything you could possibly find in Japan or Korea.

That’s where the innovation has been, and that’s where we need it, because if we don’t get the changes in there we will have one corpse after another, with enormous social danger.

Q: Is that why you wrote Innovation and Entrepreneurship?

A: I wrote the book because I felt the time had come to be a little more serious about the topic than most of the prevailing work was and also in part because, bluntly, most of the things you read or hear seem to me, on the basis of thirty years of work and experience, to be misunderstandings.

The entrepreneur—the person with George Gilder’s entrepreneurial personality—yes, there are such people, but they are rarely successful.

On the other hand, people whom Gilder would never accept as entrepreneurs are often very successful.

Entrepreneurship is not a romantic subject.

It’s hard work.

I wanted to dislodge the nineteenth-century folklore that holds that entrepreneurship is all about small business and new business.

Entrepreneurs range from the likes of Citibank, whom nobody has accused of being new or small or General Electric Credit—to Edward D. Jones & Co. in St. Louis, the fastest-growing American financial-services company.

But there’s another reason.

When I published Practice of Management thirty years ago, that book made it possible for people to learn how to manage, something that up to then only a few geniuses seemed able to do, and nobody could replicate it.

I sat down and made a discipline of it.

This book does the same with innovation and entrepreneurship.

Q: Well, you didn’t invent the stuff.

A: In a large part, yes.

Q: You didn’t invent the strategies. They were around before you wrote them down.

A: Not really.

Q: No? What I’m trying to say is that people were doing these things—finding market niches, promoting entrepreneurial behavior in their employees—before your book came out.

A: Yes, and everybody thought it required genius and that it could not be replicated.

Look, if you can’t replicate something because you don’t understand it, then it really hasn’t been invented; it’s only been done.

When I came into management, a lot of it had come out of engineering.

And a lot of it came out of accounting.

And some of it came out of psychology.

And some more came out of labor relations.

Each of those was considered separate, and each of them, by itself, was ineffectual.

You can’t do carpentry, you know, if you have only a saw, or only a hammer, or you never heard of a pair of pliers.

It’s when you put all those tools into one kit that you invent.

That’s what I did in large part in this book.

Q: You’re certainly one of the most accessible of the serious writers on management topics.

A: Well, I’m a professional writer, and I do not believe that obscurity is a virtue.

Q: Why do you work alone? No staff?

A: I don’t enjoy having to do work to keep other people busy.

I want to do the work I want to do and not the work I have to do because I have to pay them or they have to eat.

I’m a solo performer.

I’ve never been interested in building a firm.

I’m also not interested in managing people.

It bores me stiff.

Q: Do clients come to you now?

A: With one exception I don’t do any consulting elsewhere.

Q: Why are you interested in business? If your overarching interest is in organizations, why not study other kinds? Why not political organizations?

A: My consulting practice is now fifty / fifty profit-nonprofit.

But I didn’t come out of business.

I came out of political journalism.

In my second book, The Future of Industrial Man, I came to the conclusion that the integrating principle of modern society had become the large organization.

At that time, however, there was only the business organization around.

In this country, the business enterprise was the first of the modern institutions to emerge.

I decided that I needed to be inside, to really study a big company from the inside: as a human, social, political organization—as an integrating mechanism.

I tried to get inside, and I had met quite a few people as a journalist and as an investment banker.

They all turned me down.

The chairman of Westinghouse was very nice to me when I came to see him, but when I told him what I wanted he not only threw me out, he gave instructions to his staff not to allow me near the building because I was a Bolshevik.

This was 1940.

By 1942, I was doing quite a bit of work for the government.

I had given up looking for a company to study when one day the telephone rang and the fellow said, “My name is Paul Garrett, and I am vice-president of public relations for General Motors Corp.

My vice-chairman has asked me to call you to ask whether you would be willing and available to make a study of our top management structure.”

Since then, nobody at General Motors has ever admitted to having been responsible for this, but that is how I got into business.

Q: You look at business from a position that is unique. You’re neither an academic

A: Though I’ve been teaching for fifty years.

Q: But you don’t consider yourself an academic. And you certainly don’t write like an academic.

A: That is, you know, a slur on academics.

It is only in the last twenty or thirty years that being incomprehensible has become a virtue in academia.

Q: Nor are you an operations person.

A: No, I’m no good at operations.

Q: So you don’t get down there in the mud with your clients.

A: Oh yes, a little.

Look, whatever problem a client has is my problem.

Here is that mutual fund company that sees that the market is shifting from sales commissions to no front-end loads.

A terrific problem, they said.

I said, no, it’s an opportunity.

The salesman has to get his commission right away, and the customer has to pay it over five years.

That’s a tax shelter.

Make it into something that, if you hold it for five years, you pay not income tax but capital gains tax on it.

Then you’ll have a new product.

It’s been the greatest success in the mutual fund industry.

That’s nitty-gritty enough, isn’t it?

I let him do all the work, and he consults the lawyers.

I could do it, too, but he doesn’t need me to sit down with his lawyers and write out the prospectus for the SEC.

Q: Do you read the new management books that come out?

A: I look at a great deal of them.

Once in a while you get a book by a practitioner, like [Intel Corp. president] Andy Grove’s book, High Output Management, on how one maintains the entrepreneurial spirit in a very big and rapidly growing company.

I think that’s a beautiful book and very important.

But in order to get a book like that, I plow through a lot of zeros.

Fortunately, the body processes cellulose very rapidly.

Q: It doesn’t bother you that Tom Peters and Bob Waterman got rich and famous for a book built on ideas, Peters has said, that you had already written about?

A: No. The strength of the Peters book is that it forces you to look at the fundamentals.

The book’s great weakness—which is a strength from the point of view of its success—is that it makes managing sound so incredibly easy.

All you have to do is put that book under your pillow, and it’ll get done.

Q: What do you do with your leisure time?

A: What leisure time?

Q: Maybe I should have asked if you have any?

A: On my seventieth birthday, I gave myself two presents.

One was finishing my first novel and the other was a second professorship, this one in Japanese art.

For fifty years, I’ve been interested in Oriental art, and now I’ve reached a point where I’m considered, especially in Japan, to be the expert in certain narrow areas—advising museums, helping collectors.

That takes a fair amount of time.

Also, I don’t know how many hundreds or thousands of people there are now all over the world who were either clients of mine or students and who take the telephone and call to hear themselves talk and for advice.

I swim a great deal and I walk a great deal.

But leisure time in the sense of going bowling, no.

Q: How do you write?

A: Unsystematically.

It’s a compulsion neurosis.

There’s no pattern.

Q: Do you use a typewriter?

A: Sometimes. It depends.

And I never know in advance how it’s going to work.

Q: How long, for example, does it take you to write a Wall Street Journal column?

A: To write it, not very long—a day.

To do it, much longer.

They’re only fourteen hundred, fifteen hundred words.

I recently did a huge piece on the hostile takeover wave—six thousand, seven thousand words—for The Public Interest.

I had to change quite a bit.

It suddenly hit me that I know what a hostile takeover is, but how many readers do?

That had to be explained.

I totally changed the structure, and that takes a long time for me.

Once I understand it, though, I can do it very fast.

See, I’ve made my living as a journalist since I was twenty.

My first job was on a paper that published almost as much copy as The Boston Globe.

The Globe has 350 editorial employees; we were 14 employees fifty years ago, which is much healthier.

On my first day—I was barely twenty—I was expected to write two editorials.

Q: If the business of America is business, and all that sort of thing, why don’t businesspeople have a better popular image than they do?

A: The nice thing about this country is that nobody’s popular except people who don’t matter.

This is very safe.

Rock stars are popular, because no rock star has ever lasted for more than a few years.

Rock stars are therefore harmless.

The wonderful thing about this country is the universal persecution mania.

Every group feels that it is being despised and persecuted.

Have you ever heard the doctors talk about how nobody appreciates how much they bleed for the good of humanity?

Everybody is persecuted.

Everybody feels terribly sorry for himself.

You sit down with university professors, and it is unbelievable how terrible their lot is.

The businessman feels unloved, misunderstood, and neglected.

And have you ever sat down with labor leaders?

They are all of them right.

It’s all true.

This is not a country that has great respect, and this is one of its great safeguards against tyranny.

We save our adulation for people who will never become a menace—for baseball players and rock stars and movie idols who are completely innocuous.

We have respect for accomplishment, but not for status.

There is no status in this country.

There’s respect for the office of the president, but no respect for the president.

As a consequence, here, everybody feels persecuted and misunderstood, not appreciated, which I think is wonderful.

Q: Would you like to say something disrespectful about economists?

A: Yes.

Economists never know anything until twenty years later.

There are no slower learners than economists.

There is no greater obstacle to learning than to be the prisoner of totally invalid but dogmatic theories.

The economists are where the theologians were in 1300: prematurely dogmatic.

Until fifty years ago, economists had been becomingly humble and said all the time, “We don’t know.”

Before 1929, nobody believed that government had any responsibility for the economy.

Economists said, “Since we don’t know, the only policy with a chance for success is no policy.

Keep expenditures low, productivity high, and pray.”

But after 1929, government took charge of the economy and economists were forced to become dogmatic, because suddenly they were policymakers.

They began asserting, Keynes first, that they had the answers, and what’s more the answers were pleasant.

It was like a doctor telling you that you have inoperable liver cancer, but it will be cured if you go to bed with a beautiful seventeen-year-old.

Keynes said there’s no problem that can’t be cured if only you keep purchasing power high.

What could be nicer?

The monetarist treatment is even easier: There’s nothing that won’t be cured if you just increase the money supply by 3 percent per year, which is also increasing incomes.

The supply-siders are more pleasant still: There’s no disease that can’t be cured by cutting taxes.

We have no economic theory today.

But we have as many economists as the year 1300 had theologians.

Not one of them, however, will ever be sainted.

By 1300, the age of saints was over, more or less, and there is nothing worse than the theologian who no longer has faith.

That’s what our economists are today.

Q: What about government? Do you see any signs that the entrepreneurial society has penetrated government as an organization?

A: The basic problem of American government today is that it no longer attracts good people.

They know that nothing can be done; government is a dead-end street.

Partly it’s because, as in business, all the pipelines are full, but also because nobody has belief in government.

Fifty years ago, even twenty years ago, government was the place where the ideas were, the innovation, the new things.

Japan is the only country where government is still respected and where government service still attracts the top people.

Q: So there’s nothing for government to do, in your view?

A: Oh, no, no.

The days of the welfare state are over, but we are not going to abolish it.

We have to find its limits.

What are the limits?

At what point does welfare do damage?

This is the real question, and it’s brought up by the success of the welfare state.

The problems of success, I think, are the basic issues ahead of us, and the only thing I can tell you is that they don’t fit the political alignments of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

They do not fit liberal and conservative and socialist.

The traditional parties make absolutely no sense whatever to anybody of age thirty.

And yet, what else is there?

Q: Is Ronald Reagan administration promoting or inhibiting this entrepreneurial society of yours?

A: It’s a very interesting administration: totally schizophrenic.

When you look at its deeds, it hasn’t done one darn thing Mr. Carter wouldn’t have done.

And probably he wouldn’t have done it any worse either, or any better.

The words, however, are different.

This is a very clear symptom, I think, that there has been an irrevocable shift in the last ten years.

No matter who is in power, he would no longer believe in big government and would preach cutting expenses and would end up doing nothing about it.

This is because we, the American people, are at that interesting point where we are all in favor of cutting the deficit—at somebody else’s expense.

It’s a very typical stage in alcoholism, you know, where you know you have to stop—tomorrow.

Q: Do you think we will?

A: Alcoholics usually don’t reform until they’re in the gutter.

Maybe we won’t wait that long.

Three years ago, to do anything about Social Security would have been unspeakable.

Now it’s speakable.

It’s not doable yet, but I think we’re inching toward solutions.

Q: You’re not too worried about the future then?

A: Well, one can get awfully pessimistic about the world.

It’s clearly not in good shape, but it probably never has been, not in my lifetime.

One of my very early childhood memories is the outbreak of World War I. My father and his brother-in-law, who was a very famous lawyer, jurist, and philosopher, and my father’s close friend at the time, who was Tomás Masaryk, the founder of Czechoslovakia, a great historian and much older of course.

… I still remember our house.

Hot-air heating pipes carry sound beautifully.

Our bathroom was above my father’s study.

I was not quite five, and I listened at the hot-air register to my father and my uncle Hans and Masaryk saying, “This is the end not just of Austria, but of civilization.”

That is the first thing that I can remember clearly.

And then I remember the endless obituaries in the newspaper.

That’s the world I grew up in and was very conscious of, the last days of anything that had any value.

And it hasn’t changed since.

So it’s awfully easy for me to be pessimistic, but what’s the use of it?

Lots of things worry me.

On the other hand, we have survived against all odds.

Q: It’s hard to place you, politically …

A: I’m an old—not a neo—conservative.

The neoconservatives started out on the Left, and now they are basically old-fashioned liberals, which is respectable, but I’ve never been one.

For instance, although I believe in the free market, I have serious reservations about capitalism.

Any system that makes one value absolute is wrong.

Basically, the question is not what are our rights, but what are our responsibilities.

These are very old conservative approaches, and I raised them in the first book I wrote, The End of Economic Man, when I was in my twenties, so I have not changed.

Q: Were you ever tempted to go into politics?

A: No, I realized very early that I was apolitical, in the sense that I hadn’t the slightest interest in power for myself.

And if you have no interest in power, you are basically a misfit in politics.

On the other hand, give me a piece of paper and pencil, and I start to enjoy myself.

Q: What other things cheer you?

A: I am very much impressed by the young people.

First, that most of the things you hear about them are nonsense, for example, complaints that they don’t work.

I think that basically they’re workaholics.

And there is a sense of achievement there.

But I’m glad that I’m not twenty-five years old.

It’s a very harsh world, a terribly harsh world for young people.

[1985]

This interview was conducted by senior writer Tom Richman and appeared in the October 1985 issue of Inc.

The Changed World Economy

There is a lot of talk today of the changing world economy.

But—and this is the point of this chapter—the world economy is not changing.

It has already changed in its foundations and in its structure, and irreversibly so in all probability.

Within the last ten or fifteen years, three fundamental changes have occurred in the very fabric of the world’s economy:

1. The primary-products economy has come “uncoupled” from the industrial economy;

2. In the industrial economy itself, production has come uncoupled from employment;

3. Capital movements rather than trade in goods and services have become the engines and driving force of the world economy.

The two have not, perhaps, become uncoupled.

But the link has become quite loose, and worse, quite unpredictable.

These changes are permanent rather than cyclical.

We may never understand what caused them—the causes of economic change are rarely simple.

It may be a long time before economic theorists accept that there have been fundamental changes, and longer still before they adapt their theories to account for them.

They will surely be most reluctant, above all, to accept that the world economy is in control rather than the macroeconomics of the national state, on which most economic theory still exclusively focuses.

Yet this is the clear lesson of the success stories of the last twenty years: of Japan and South Korea; of West Germany, actually a more impressive though far less flamboyant performance than Japan; and of the one great success within the United States, the turnaround and rapid rise of an industrial New England that, only twenty years ago, was widely considered moribund.

But practitioners, whether in government or in business, cannot wait till there is a new theory, however badly needed.

They have to act.

And then their actions will be the more likely to succeed the more they are being based on the new realities of a changed world economy.

The Primary-Products Economy

The collapse in nonoil commodity prices began in 1977 and has continued, interrupted only once, right after the 1979 petroleum panic, by a speculative burst that lasted less than six months and was followed by the fastest drop in commodity prices ever recorded.

In early 1986, overall, raw-materials prices (other than petroleum*) were at the lowest level in recorded history in relation to the prices of manufactured goods and services—as low as in 1932, and in some cases (lead and copper) lower than at the depths of the Great Depression.

The collapse of raw-materials prices and the slowdown of raw-materials demand is in startling contrast to what was confidently predicted.

Ten years ago The Report of the Club of Rome predicted that desperate shortages for all raw materials were an absolute certainty by the year 1985.

Even more recently, in 1980 the Global 2000 Report of President Carter’s administration concluded that world demand for food would increase steadily for at least twenty years; that food production worldwide would go down except in developed countries; and that real food prices would double.

This forecast largely explains why American farmers bought up whatever farmland was available, thus loading on themselves the debt burden that now threatens so many of them.

But contrary to all these predictions, agricultural output in the world actually rose almost a full third between 1972 and 1985 to reach an all-time high.

And it rose the fastest in less developed countries.

Similarly, production of practically all forest products, metals, and minerals has been going up between 20 and 35 percent in these last ten years, again with production rising the fastest in less developed countries.

And there is not the slightest reason to believe that the growth rates will be slackening, despite the collapse of prices.

Indeed, as far as farm products are concerned, the biggest increase, at an almost exponential rate of growth, may still be ahead.*

But perhaps even more amazing than the contrast between what everybody expected and what happened is that the collapse in the raw-materials economy seems to have had almost no impact on the industrial economy of the world.

Yet, if there was one thing that was “known”—and considered “proved” without doubt in business cycle theory, it was that a sharp and prolonged drop in raw-materials prices inevitably, and within eighteen months to two and a half years, brings on a worldwide depression in the industrial economy.

The industrial economy of the world is surely not normal by any definition of the term.

But it is also surely not in a worldwide depression.

Indeed, industrial production in the developed noncommunist countries has continued to grow steadily, albeit at a somewhat slower rate, especially in Western Europe.

Of course the depression in the industrial economy may only have been postponed and may still be triggered, for instance, by a banking crisis caused by massive defaults on the part of commodity-producing debtors, whether in the Third World or in Iowa.

But for almost ten years, the industrial world has run as though there were no raw-materials crisis at all.

The only explanation is that for the developed countries—excepting only the Soviet Union—the primary-products sector has become marginal where it had always been central before.

In the late 192os, before the Great Depression, farmers still constituted nearly one-third of the U.S. population, and farm income accounted for almost a quarter of the gross national product (GNP).

Today they account for one-twentieth of the population and GNP, respectively.

Even adding the contribution that foreign raw-materials and farm producers make to the American economy through their purchases of American industrial goods, the total contribution of the raw-materials and food-producing economies of the world to the American GNP is, at most, one-eighth.

In most other developed countries, the share of the raw-materials sector is even lower than in the United States.

Only in the Soviet Union is the farm still a major employer, with almost a quarter of the labor force working on the land.

The raw-materials economy has thus come uncoupled from the industrial economy.

This is a major structural change in the world economy, with tremendous implications for economic and social policy and economic theory, in developed and developing countries alike.

For example, if the ratio between the prices of manufactured goods and the prices of primary products (other than petroleum)—that is, of foods, forest products, metals, and minerals—had been the same in 1985 as it had been in 1973, or even in 1979, the U.S. trade deficit in 1985 might have been a full third less, $100 billion as against an actual $150 billion.

Even the U.S. trade deficit with Japan might have been almost a third lower, some $35 billion as against $50 billion.

American farm exports would have brought almost twice as much.

And our industrial exports to one of our major customers, Latin America, would have held; their near-collapse alone accounts for a full one-sixth of the deterioration in U.S. foreign trade.

If primary-products prices had not collapsed, America’s balance of payments might even have shown a substantial surplus.

Conversely, Japan’s trade surplus with the world might have been a full one-fifth lower.

And Brazil in the last few years would have had an export surplus almost 50 percent higher than its actual one.

Brazil would then have had little difficulty meeting the interest on its foreign debt and would not have had to endanger its economic growth by drastically curtailing imports as it did.

Altogether, if raw-materials prices in relationship to manufactured goods prices had remained at the 1973 or even the 1979 level, there would be no crisis for most debtor countries, especially in Latin America.

What has happened?

And what is the outlook?

Demand for food has actually grown almost as fast as the Club of Rome and the Global 2000 Report anticipated.

But the supply has been growing much faster.

It not only has kept pace with population growth; it steadily outran it.

One cause of this, paradoxically, is surely the fear of worldwide food shortages, if not of world famine.

It resulted in tremendous efforts to increase food output.

The United States led the parade with a farm policy successfully aiming (except in one year: 1983) at subsidizing increased food production.

The European Common Market followed suit, and even more successfully.

The greatest increases, both in absolute and in relative terms, have, however, been in developing countries: in India, in post-Mao China, and in the rice-growing countries of Southeast Asia.

And then there is also the tremendous cut in waste.

Twenty-five years ago, up to 80 percent of the grain harvest of India fed rats and insects rather than human beings.

Today in most parts of India the wastage is down to 20 percent, the result of such unspectacular but effective infrastructure innovations as small concrete storage bins, insecticides, or three-wheeled motorized carts that take the harvest straight to a processing plant instead of letting it sit in the open for weeks on end.

And it is not too fanciful to expect that the true revolution on the farm is still ahead.

Vast tracts of land that hitherto were practically barren are being made fertile, either through new methods of cultivation or through adding trace minerals to the soil: the sour clays in the Brazilian highlands, for instance, or aluminum-contaminated soils in neighboring Peru, which never produced anything before and which now produce substantial quantities of high-quality rice.

Even greater advances are registered in biotechnology, both in preventing diseases of plants and animals and in increasing yields.

In other words, just as the population growth of the world is slowing down, and in many parts quite dramatically, food production is likely to increase sharply.

But import markets for food have all but disappeared.

As a result of its agricultural drive, Western Europe has become a substantial food exporter plagued increasingly by unsalable surpluses of all kinds of foods, from dairy products to wine and from wheat to beef.

China, some observers now predict, will have become a food exporter by the year 2000.

India has already reached that stage, especially in respect to wheat and coarse grains.

Of all major noncommunist countries only Japan is still a substantial food importer, buying abroad about one-third of her food needs.

Today most of this comes from the United States.

Within five or ten years, however, South Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia—low-cost producers that are increasing food output fast—will compete with the United States to become Japan’s major suppliers.

The only remaining major world-market food buyer may then be the Soviet Union, and Russia’s food needs are likely to grow.

However, the food surpluses in the world are so large, maybe five to eight times what Russia would ever need to buy, that the Russian food needs are not by themselves enough to put upward pressure on world prices.

On the contrary, the competition for access to the Russian market among the surplus producers—the United States, Europe, Argentina, Australia, New Zealand (and, probably within a few years, India as well)—is already so intense as to knock down world food prices.

For practically all nonfarm commodities, whether forest products, minerals, or metals, world demand itself—in sharp contrast to what the Club of Rome so confidently predicted—is shrinking.

Indeed, the amount of raw materials needed for a given unit of economic output has been dropping for the entire century, except in wartime.

A recent study by the International Monetary Fund* calculates the decline as being at the rate of one and a quarter percent a year (compound) ever since 1900.

That would mean that the amount of industrial raw materials needed for one unit of industrial production is now no more than two-fifths of what it was in 1900, and the decline is accelerating.

Even more startling are recent Japanese developments.

In 1984, Japan, for every unit of industrial production, consumed only 6o percent of the raw materials she had consumed for the same amount of industrial production in 1973, only eleven years earlier.

Why this decline?

It is not that industrial production is becoming less important, a common myth for which, as we shall see shortly, there is not the slightest evidence.

What is happening is much more important.

Industrial production is steadily switching from heavily material-intensive to far less material-intensive products and processes.

One reason for this is the emergence of the new and especially the high-tech industries.

The raw materials in a semiconductor microchip account for 1 to 3 percent; in an automobile their share is 40 percent; and in pots and pans, 60 percent.

But the same scaling down of raw-material needs goes on in old industries, and with respect to old products as well as new ones.

Fifty to one hundred pounds of fiberglass cable transmits as many telephone messages as does one ton of copper wire, if not more.

This steady drop in the raw-material intensity of manufacturing processes and manufacturing products extends to energy as well, and especially to petroleum.

To produce one hundred pounds of fiberglass cable requires no more than one-twentieth of the energy needed to mine and smelt enough copper ore to produce one ton of copper and then to draw it out into copper wire.

Similarly plastics, which are increasingly replacing steel in automobile bodies, represent a raw-materials cost, including energy, of less than half that of steel.

And if copper prices were to double—and that would still mean a fairly low price by historical standards—we would soon start to “mine” the world’s largest copper deposits, which are not the mines of Chile or of Utah, but the millions of tons of telephone cable under the streets of our large cities.

It would then pay us to replace the underground copper cables with fiberglass.

Thus it is quite unlikely that raw-materials prices will rise substantially compared to the prices of manufactured goods (or of high-knowledge services such as information, education, or health care) except in the event of a major prolonged war.

One implication of this sharp shift in the terms of trade of primary products concerns the developed countries, whether major raw-materials exporters like the United States or major raw-materials importers such as Japan.

The United States for two centuries has seen maintenance of open markets for its farm products and raw materials as central to its international trade policy.

This is in effect what is meant in the United States by an “open world economy” and by “free trade.”

Does this still make sense?

Or does the United States instead have to accept that foreign markets for its foodstuffs and raw materials are in long-term and irreversible decline?

But also, does it still make sense for Japan to base its international economic policy on the need to earn enough foreign exchange to pay for imports of raw materials and foodstuffs?

Since Japan opened herself to the outside world 120 years ago, preoccupation, amounting almost to a national obsession, with this dependence on raw-materials and food imports has been the driving force of

Japan’s policy, and not in economics alone.

But now Japan might well start out with the assumption, a far more realistic one in today’s world, that foodstuffs and raw materials are in permanent oversupply.

Taken to their logical conclusion, these developments might mean that some variant of the traditional Japanese policy—highly “mercantilist” with strong deemphasis of domestic consumption and equally strong emphasis on capital formation, and with protection of “infant” industries—might suit the United States better than its own traditions.

Conversely the Japanese might be better served by some variant of America’s traditional policies, and especially by shifting from favoring savings and capital formation to favoring consumption.

But is such a radical break with a hundred years and more of political convictions and commitments likely?

Still, from now on the fundamentals of economic policy are certain to come under increasing criticism in these two countries, and in all other developed countries as well.

They will also, however, come under increasing scrutiny in major Third World nations.

For if primary products are becoming of marginal importance to the economics of the developed world, traditional development theories and traditional development policies are losing their foundations.

All of them are based on the assumption, historically a perfectly valid one, that developing countries pay for imports of capital goods by exporting primary materials—farm and forest products, minerals, metals.

All development theories, however much they differ otherwise, further assume that raw-materials purchases on the part of the industrially developed countries must rise at least as fast as industrial production in these countries.

This then implies that, over any extended period of time, any raw-materials producer becomes a better credit risk and shows a more favorable balance of trade.

But this has become highly doubtful.

On what foundation, then, can economic development be based, especially in countries that do not have a large enough population to develop an industrial economy based on the home market?

And, as we shall presently see, economic development of these countries can also no longer be based on low labor costs.

What “De-Industrialization” Means

The second major change in the world economy is the uncoupling of manufacturing production from manufacturing employment.

To increase manufacturing production in developed countries has actually come to mean decreasing blue-collar employment.

As a consequence, labor costs are becoming less and less important as a “comparative cost” and as a factor in competition.

There is a great deal of talk these days about the “deindustrialization” of America.

But in fact, manufacturing production has gone up steadily in absolute volume and has not gone down at all as a percentage of the total economy.

Ever since the end of the Korean War, that is, for more than thirty years, it has held steady at around 23 to 24 percent of America’s total GNP.

It has similarly remained at its traditional level in all of the major industrial countries.

It is not even true that American industry is doing poorly as an exporter.

To be sure, this country is importing far more manufactured goods than it ever did from both Japan and Germany.

But it is also exporting more than ever before—despite the heavy disadvantage in 1983, 1984, and most of 1985 of a very expensive dollar, of wage increases larger than our main competitors had, and of the near-collapse of one of our main industrial markets, Latin America.

In 1984, the year the dollar soared, exports of American manufactured goods rose by 8.3 percent, and they went up again in 1985.

The share of U.S. -manufactured exports in world exports was 17 percent in 1978.

By 1985 it had risen to 20 percent, with West Germany accounting for 18 percent and Japan for 16 (the three countries together thus accounting for more than half of the total).

Thus it is not the American economy that is being “deindustrialized.”

It is the American labor force.

Between 1973 and 1985, manufacturing production in the United States actually rose by almost 40 percent.

Yet manufacturing employment during that period went down steadily.

There are now million fewer people employed in blue-collar work in the American manufacturing industry than there were in 1975.

Yet in the last twelve years total employment in the United States grew faster than at any time in the peacetime history of any country—from 82 to 110 million between 1973 and 1985, that is, by a full third.

The entire growth, however, was in nonmanufacturing, and especially in non-blue-collar jobs.

The trend itself is not new.

In the 1920s, one out of every three Americans in the labor force was a blue-collar worker in manufacturing.

In the 1950s, the figure was still one in every four.

It now is down to one in every six—and dropping.

But although the trend has been running for a long time, it has lately accelerated to the point where, in peacetime at least, no increase in manufacturing production, no matter how large, is likely to reverse the long-term decline in the number of blue-collar jobs in manufacturing or in their proportion of the labor force.

And the trend is the same in all developed countries and is, indeed, even more pronounced in Japan.

It is therefore highly probable that developed countries such as the United States or Japan will, by the year 2010, employ no larger a proportion of the labor force in manufacturing than developed countries now employ in farming—at most, one-tenth.

Today the United States employs around iS million people in blue-collar jobs in the manufacturing industry.

Twenty-five years hence the number is likely to be 10—at most, 12—million.

In some major industries the drop will be even sharper.

It is quite unrealistic, for instance, to expect the American automobile industry to employ, twenty-five years hence, more than one-third of its present blue-collar force, even though production might be 50 percent higher.

If a company, an industry, or a country does not succeed in the next quarter century in sharply increasing manufacturing production, while sharply reducing the blue-collar work force, it cannot hope to remain competitive, or even to remain “developed.”

It would decline fairly fast.

Great Britain has been in industrial decline these last twenty-five years, largely because the number of blue-collar workers per unit of manufacturing production went down far more slowly than in all other noncommunist developed countries.

Yet Britain has the highest unemployment rate among noncommunist developed countries: more than 13 percent.

The British example indicates a new but critical economic equation: A country, an industry, or a company that puts the preservation of blue-collar manufacturing jobs ahead of being internationally competitive (and that implies steady shrinkage of such jobs) will soon have neither production nor steady jobs.

The attempt to preserve industrial blue-collar jobs is actually a prescription for unemployment.

On the national level, this is accepted only in Japan so far.

Indeed, Japanese planners, whether those of the government or those of private business, start out with the assumption of a doubling of production within fifteen or twenty years based on a cut in blue-collar employment of 25 to 40 percent.

And a good many large American companies such as IBM, General Electric, or the big automobile companies forecast parallel development.

Implicit in this is also the paradoxical fact that a country will have the less general unemployment the faster it shrinks blue-collar employment in manufacturing.

But this is not a ‘conclusion that politicians, labor leaders, or indeed the general public can easily understand or accept.

What will confuse the issue even more is that we are experiencing several separate and different shifts in the manufacturing economy.

One is the acceleration of the substitution of knowledge and capital for manual labor.

Where we spoke of mechanization a few decades ago, we now speak of robotization or automation.

This is actually more a change in terminology than a change in reality.

When Henry Ford introduced the assembly line in 1909, he cut the number of man-hours required to produce a motorcar by some 80 percent in two or three years: far more than anybody expects to happen as a result even of the most complete robotization.

But there is no doubt that we are facing a new, sharp acceleration in the replacement of manual workers by machines, that is, by the products of knowledge.

A second development—and in the long run it may be fully as important if not more important—is the shift from industries that are primarily labor-intensive to industries that, from the beginning, are primarily knowledge-intensive.

The costs of the semiconductor microchip are about 70 percent knowledge and no more than 12 percent labor.

Similarly, of the manufacturing costs of prescription drugs, “labor” represents no more than 10 or 15 percent, with knowledge—research, development, and clinical testing—representing almost 50 percent.

By contrast, in the most fully robotized automobile plant labor would still account for 20 or 25 percent of the costs.

Another, and highly confusing, development in manufacturing is the reversal of the dynamics of size.

Since the early years of this century, the trend in all developed countries has been toward larger and ever larger manufacturing plants.

The “economies of scale” greatly favored them.

Perhaps equally important, what one might call the economies of management favored them.

Up until recently, modern management seemed to be applicable only to fairly large units.

This has been reversed with a vengeance the last fifteen to twenty years.

The entire shrinkage in manufacturing jobs in the United States has been in large companies, beginning with the giants in steel and automobiles.

Small and especially medium-size manufacturers have either held their own or actually added people.

In respect to market standing, exports, and profitability too, smaller and especially middle-size businesses have done remarkably better than the big ones.

The same reversal of the dynamics of size is occurring in the other developed countries as well, even in Japan, where bigger was always better and biggest meant best!

The trend has reversed itself even in old industries.

The most profitable automobile company these last years has not been one of the giants, but a medium-size manufacturer in Germany: BMW.

The only profitable steel companies worldwide have been medium-size makers of specialty products, such as oil-drilling pipe, whether in the United States, in Sweden, or in Japan.

In part, especially in the United States,* this is a result of a resurgence of entrepreneurship.

But perhaps equally important, we have learned in the last thirty years how to manage the small and medium-size enterprise—to the point that the advantages of smaller size, for example, ease of communications and nearness to market and customer, increasingly outweigh what had been forbidding management limitations.

Thus the United States, but increasingly in the other leading manufacturing nations such as Japan and West Germany, the dynamism in the economy has shifted from the very big companies that dominated the world’s industrial economy for thirty cars after World War II to companies that, while much smailer, are still professionally managed and, largely, publicly financed.

But also there are emerging two distinct kinds of “manufacturing industry”: one group that is materials-based, the industries that provided economic growth in the first three-quarters of this century; and another group that is information, and knowledge-based, pharmaceuticals, telecommunications, analytical instruments, information processing such as computers, and so on.

And increasingly it is in the information-based manufacturing industries in which growth has come to center.

These two groups differ in their economic characteristics and especially in respect to their position in the international economy.

The products of materials-based industries have to be exported or imported as products.

They appear in the balance of trade.

The products of information-based industries can be exported or imported both as products and as services.

An old example is the printed book.

For one major scientific publishing company, “foreign earnings” account for two-thirds of total revenues.

Yet the company exports few books, if any; books are heavy.

It sells “rights.”

Similarly, the most profitable computer “export sale” may actually show up in the statistics as an “import.”

It is the fee some of the world’s leading banks, some of the big multinationals, and some Japanese trading companies get for processing in their home offices data sent in electronically from their branches or their customers anywhere in the world.

In all developed countries, knowledge workers have already become the center of gravity of the labor force, even in numbers.

Even in manufacturing they will outnumber blue-collar workers within fewer than ten years.

And then, exporting knowledge so that it produces license income, service fees, and royalties may actually create substantially more jobs than exporting goods.

This then requires, as official Washington has apparently already realized, far greater emphasis in trade policy on “invisible trade” and on abolishing the barriers, mostly of the non-tariff kind, to the trade in services, such as information, finance and insurance, retailing, patents, and even health care.

Indeed, within twenty years the income from invisible trade might easily be larger, for major developed countries, than the income from the export of goods.

Traditionally, invisible trade has been treated as a stepchild, if it received any attention at all.

Increasingly, it will become central.

Another implication of the uncoupling of manufacturing production from manufacturing employment is, however, that the choice between an industrial policy that favors industrial production and one that favors industrial employment is going to be a singularly contentious political issue for the rest of this century.

Historically these have always been considered two sides of the same coin.

From now on, however, the two will increasingly pull in different directions and are indeed becoming alternatives, if not incompatible.

“Benevolent neglect”—the policy of the Reagan administration these last few years—may be the best policy one can hope for, and the only one with a chance of success.

It is not an accident, perhaps, that the United States has, next to Japan, by far the lowest unemployment rate of any industrially developed country.

Still, there is surely need also for systematic efforts to retrain and to replace redundant blue-collar workers—something that no one as yet knows how to do successfully.

«§§§»

Finally, low labor costs are likely to become less and less of an advantage in international trade, simply because in the developed countries they are going to account for less and less of total costs.

But also, the total costs of automated processes are lower than even those of traditional plants with low labor costs, mainly because automation eliminates the hidden but very high costs of “not working,” such as the costs of poor quality and of rejects, and the costs of shutting down the machinery to change from one model of a product to another.

Examples are two automated U.S. producers of television receivers, Motorola and RCA.

Both were almost driven out of the market by imports from countries with much lower labor costs.

Both then automated, with the result that their American-made products successfully compete with foreign imports.

Similarly, some highly automated textile mills in the Carolinas can underbid imports from countries with very low labor costs, for example, Thailand.

Conversely, in producing semiconductors, some American companies have low labor costs because they do the labor-intensive work offshore, for instance, in West Africa.

Yet they are the high-cost producers, with the heavily automated Japanese easily underbidding them, despite much higher labor costs.

The cost of capital will thus become increasingly important in international competition.

And it is the cost in respect to which the United States has become, in the last ten years, the highest-cost country—and Japan the lowest-cost one.

A reversal of the U.S. policy of high interest rates and of high cost of equity capital should thus be a priority of American policymakers, the direct opposite of what has been U.S. policy for the past five years.

But this, of course, demands that cutting the government deficit rather than high interest rates becomes our defense against inflation.

For developed countries, and especially for the United States, the steady downgrading of labor costs as a major competitive factor could be a positive development.

For the Third World, and especially for the rapidly industrializing countries—Brazil, for instance, or South Korea or Mexico—it is, however, bad news.

Of the rapidly industrializing countries of the nineteenth century, one, Japan, developed herself by exporting raw materials, mainly silk and tea, at steadily rising prices.

One, Germany, developed by “leapfrogging” into the “high-tech” industries of its time, mainly electricity, chemicals, and optics.

The third rapidly industrializing country of the nineteenth century, the United States, did both.

Both ways are blocked for the present rapidly industrializing countries: the first one because of the deterioration of the terms of trade for primary products, the second one because it requires an “infrastructure” of knowledge and education far beyond the reach of a poor country (although South Korea is reaching for it!).

Competition based on lower labor costs seemed to be the way out.

Is this way going to be blocked too?

From “Real” to “Symbol” Economy

The third major change is the emergence of the symbol economy—capital movements, exchange rates and credit flow—as the flywheel of the world economy, in the place of the real economy: the flow of goods and services—and largely independent of the latter.

It is both the most visible and yet the least understood of the changes.

World trade in goods is larger, much larger, than it has ever been before.

And so is the invisible trade, the trade in services.

Together, the two amount to around $2.5 to $3 trillion a year.

But the London Eurodollar market, in which the world’s financial institutions borrow from and lend to each other, turns over $300 billion each working day, or $75 trillion a year, that is, at least twenty-five times the volume of world trade.

In addition, there are the (largely separate) foreign-exchange transactions in the world’s main money centers, in which one currency is traded against another (for example, U.S. dollars against the Japanese yen).

These run around $150 billion a day, or about $35 trillion a year: twelve times the worldwide trade in goods and services.

No matter how many of these Eurodollars, or yen, or Swiss francs are just being moved from one pocket into another and thus counted more than once, there is only one explanation for the discrepancy between the volume of international money transactions and the trade in goods and services: capital movements unconnected to, and indeed largely independent of, trade greatly exceed trade finance.

There is no one explanation for this explosion of international—or more accurately, transnational—money flows.

The shift from fixed to “floating” exchange rates in 1971 may have given the initial impetus (though, ironically, it was meant to do the exact opposite).

It invited currency speculation.

The surge in liquid funds flowing to Arab petroleum producers after the two “oil shocks” of 1973 and 1979 was surely a major factor.

But there can be little doubt that the American government deficit also plays a big role.

It sucks in liquid funds from all over into the “Black Hole” that the American budget has become* and thus has already made the United States into the world’s major debtor country.

Indeed, it can be argued that it is the budget deficit which underlies the American trade and payments deficit.

A trade and payments deficit is, in effect, a loan from the seller of goods and services to the buyer, that is, to the United States.

Without it the administration could not possibly finance its budget deficit, or at least not without the risk of explosive inflation.

Altogether, the extent to which major countries have learned to use the international economy to avoid tackling disagreeable domestic problems is unprecedented: the United States, for example, by using high interest rates to attract foreign capital and thus avoiding facing up to its domestic deficit, or the Japanese through pushing exports to maintain employment despite a sluggish domestic economy.

And this “politicization” of the international economy is surely also a factor in the extreme volatility and instability of capital flows and exchange rates.

Whatever the causes, they have produced a basic change: In the world economy, the real economy of goods and services and the symbol economy of money, credit and capital are no longer tightly bound to each other, and are, indeed, moving further and further apart.

Traditional international economic theory is still neoclassical and holds that trade in goods and services determines international capital flows and foreign-exchange rates.

Capital flows and foreign-exchange rates these last ten or fifteen years have, however, moved quite independently of foreign trade and indeed (for instance, in the rise of the dollar in 1984/85) have run counter to it.

But the world economy also does not fit the Keynesian model in which the symbol economy determines the real economy.

And the relationship between the turbulences in the world economy and the domestic economies has become quite obscure.

Despite its unprecedented trade deficit, the United States has, for instance, had no deflation and has barely been able to keep inflation in check.

Despite its trade deficit, the United States also has the lowest unemployment rate of any major industrial country, next to Japan.

The U.S. rate is lower, for instance, than that of West Germany, whose exports of manufactured goods and trade surpluses have been growing as fast as those of Japan.

Conversely, despite the exponential growth of Japanese exports and an unprecedented Japanese trade surplus, the Japanese domestic economy is not booming but has remained remarkably sluggish and is not generating any new jobs.

What is the outcome likely to be?

Economists take it for granted that the two, the real economy and the symbol economy, must come together again.

They do disagree, however—and quite sharply—about whether they will do so in a “soft landing” or in a head-on collision.

The soft-landing scenario-the Reagan administration is committed to it, as are the governments of most of the other developed countries-expects the U.S. government deficit and the U.S. trade deficit to go down together until both attain surplus, or at least balance, sometime in the early 1990S.

And then capital flows and exchange rates would both stabilize, with production and employment high and inflation low in major developed countries.

In sharp contrast to this is the “hard-landing” scenario.

With every deficit year the indebtedness of the U.S. government goes up, and with it the interest charges on the U.S. budget, which in turn raises the deficit even further.

Sooner or later, the argument goes, this then must undermine foreign confidence in America and the American dollar: some authorities consider this practically imminent.

Then foreigners stop lending money to the United States.

Indeed, they try to convert the dollars they hold into other currencies.

The resulting “flight from the dollar” brings the dollar’s exchange rates crashing down.