Startup thinking

Larger

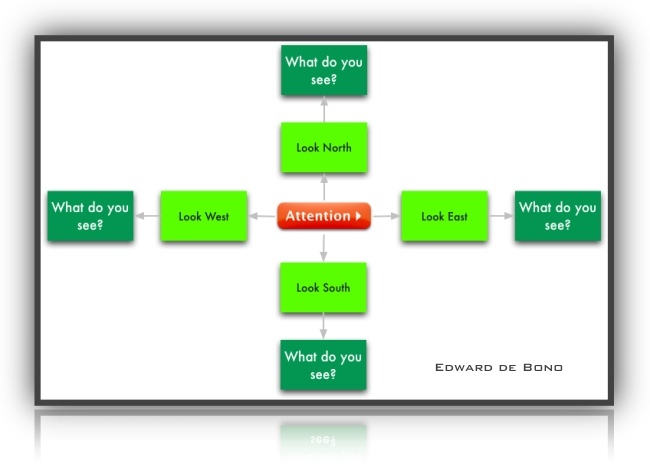

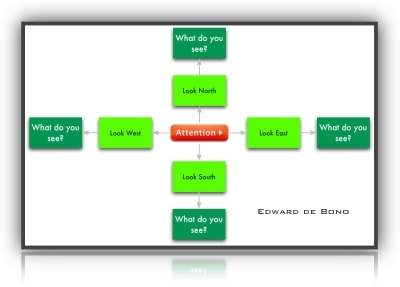

Attention

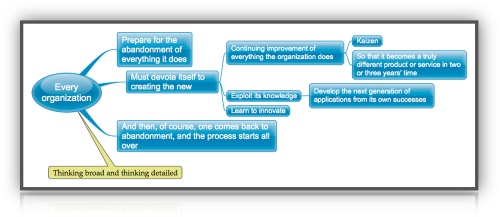

Thinking Broad and Thinking Detailed by Edward de Bono

The focus should be on what to start and that is a matter of what it contributes to the outside world that makes a difference. How to start something comes next.

Having a “bright idea” and then “selling” it is a recipe for a hard road to travel. It is the much maligned inside-out behavior that lies at the heart of enterprise and organization difficulties. For the rest of the story see chapter 10 of Innovation and Entrepreneurship

The world doesn't really need just more new businesses started by individuals. What is needed now is different — it lies in the world situation. But see “Our Entrepreneurial Economy” and consider how things might have changed.

Individuals may play a different role in today's ecology. See Career / life vision guidance from Peter Drucker

You have to learn to manage in situations where you don’t have command authority, where you are neither controlled nor controlling. That is the fundamental change. Management textbooks still talk mainly about managing subordinates. But you no longer evaluate an executive in terms of how many people report to him or her. That standard doesn’t mean as much as the complexity of the job, the information it uses and generates, and the different kinds of relationships needed to do the work.

Similarly, business news still refers to managing subsidiaries. But this is the control approach of the 1950s or 1960s. The reality is that the multinational corporation is rapidly becoming an endangered species. Businesses used to grow in one of two ways: from grass-roots up or by acquisition. In both cases, the manager had control. Today businesses grow through alliances, all kinds of dangerous liaisons and joint ventures, which, by the way, very few people understand. This new type of growth upsets the traditional manager, who believes he or she must own or control sources and markets.

Something Ventured, Nothing Gained?

Posted on Sep 26, 2012

If you feel the urge to pour your money into a venture-capital-backed, high-tech startup, you might first consider whether you’re better off playing a corner bet in roulette.

The Wall Street Journal reported recently on research by a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School, Shikhar Ghosh, who has found “evidence that venture-backed start-ups fail at far higher numbers than the rate the industry usually cites.”

Specifically, about 30% of firms eat up all the money and return nothing; about 75% of venture-backed firms in the U.S. don’t return investors’ capital; and about 95% of firms fall short of meeting the targets set by investors.

Now, to be sure, an innovative idea is a good start for a business, and if you’re in the right field, it’ll see you a long way. In his book Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Peter Drucker observed that, in many industries, “time is on the side of the innovator.”

But this is not so in what Drucker called “knowledge-based innovation,” for which there’s only a short time window and little room for error. “Here innovators do not get a second chance; they have to be right the first time,” Drucker wrote. “The environment is harsh and unforgiving. And once the ‘window’ closes, the opportunity is gone forever.”

These challenges, in Drucker’s view, are “particularly pronounced in the high-tech industries.” Because “such industries are in the limelight and thus attract far more entrants and far more capital than more mundane areas,” high-tech tends to be a riskier game “in which a middle hand is considered worthless,” he explained. With so few missteps permitted, “very few businesses in the industry have the financial resources to outlast even a short storm.”

So what is an investor to do?

Look for a start-up with indications of good management. It’s no guarantee of success, but it’s a minimum requirement. “Unless a new venture develops into a new business and makes sure of being ‘managed,’ it will not survive no matter how brilliant the entrepreneurial idea, how much money it attracts, how good its products, nor even how great the demand for them,” Drucker warned.

…

A brainroad

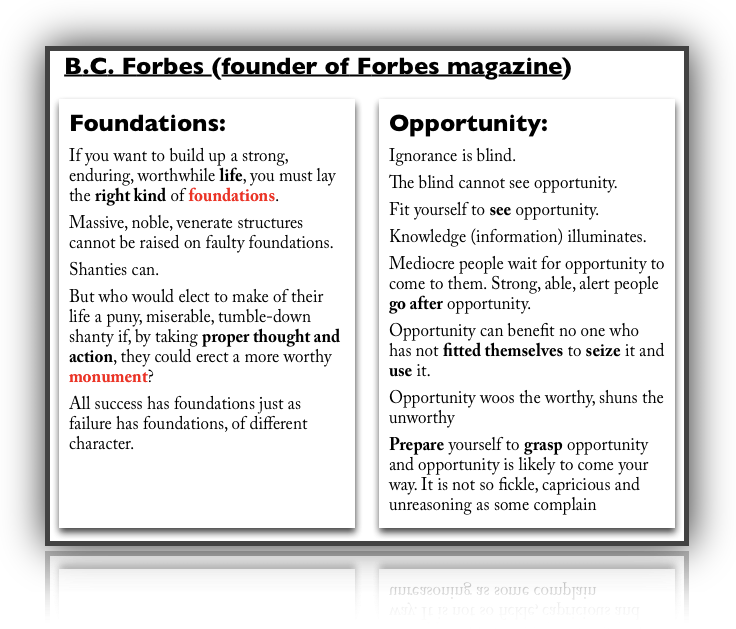

The decision to start a business has serious consequence for one’s life design. Anybody who tells you otherwise is full of crap and is playing you.

A solid foundation may help, but there are no guarantees that can be purchased or acquired otherwise.

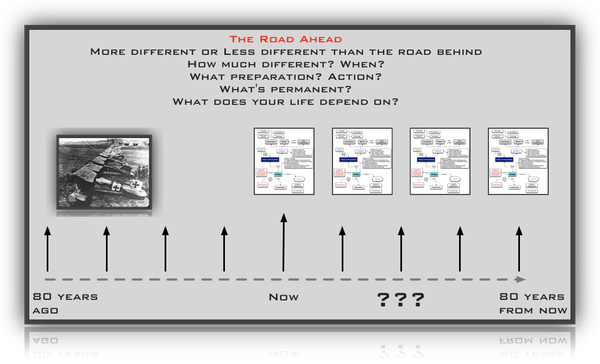

Thinking several steps ahead in order to adjust initial and subsequent directions may help — a foundation for future directed decisions. Get some help from the Uber Mentor.

A social ecologist is worlds apart from a subject expert — your brain needs to go down this road.

Below is a fairly broad range of discontinuous (a break in your current trajectory) next step options

Thinking Broad and Thinking Detailed by Edward de Bono

Post-capitalist society ::: the transformation

Management and Economic Development

Knowledge, society of organizations, management

Changing Values and Characteristics

High tech is living in the nineteenth century, the pre-management world. They believe that people pay for technology. They have a romance with technology. But people don't pay for technology: they pay for what they get out of technology. The Frontiers of Management

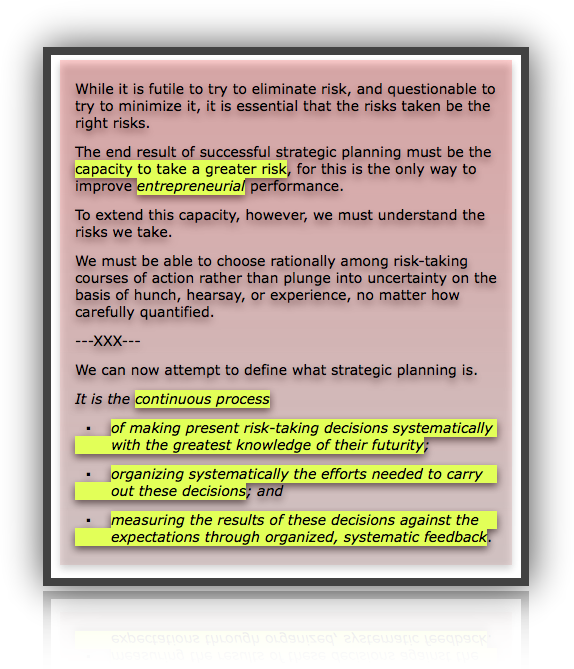

Entrepreneurship is “risky” mainly because so few of the so-called entrepreneurs know what they are doing.

They lack the methodology.

They violate elementary and well-known rules.

This is particularly true of high-tech entrepreneurs.

To be sure (as will be discussed in Chapter 9 of Innovation and Entrepreneurship), high-tech entrepreneurship and innovation are intrinsically more difficult and more risky than innovation based on economics and market structure, on demographics, or even on, something as seemingly nebulous and intangible as Weltanschauung — perceptions and moods.

But even high-tech entrepreneurship need not be “high-risk,” as Bell Lab and IBM prove.

It does need, however, to be systematic.

It needs to be managed.

Above all, it needs to be based on purposeful innovation.

Piloting from Management, Revised Edition

“Enterprises of all kinds increasingly use all kinds of market research and customer research to limit, if not eliminate, the risks of change.

But one cannot market research the truly new.

Also nothing new is right the first time.

Invariably, problems crop up that nobody even thought of.

Invariably, problems that loomed very large to the originator turn out to be trivial or not to exist at all.

Above all, the way to do the job invariably turns out to be different from what was originally designed.

It is almost a “law of nature” that anything that is truly new, whether product or service or technology, finds its major market and its major application not where the innovator and entrepreneur expected, and not to be the use for which the innovator or entrepreneur has designed it.

And that, no market or customer research can possibly discover.

The best example is an early one:

The improved steam engine that James Watt (1736-1819) designed and patented in 1776 is the event that, for most people, signifies the advent of the Industrial Revolution.

Actually, Watt until his death saw only one use for the steam engine: to pump water out of coal mines.

That was the use for which he had designed it.

And he sold it only to coal mines.

It was his partner, Matthew Boulton (1728-1809), who was the real father of the Industrial Revolution.

Boulton saw that the improved steam engine could be used in what was then England’s premier industry, textiles, and especially in the spinning and weaving of cotton.

Within ten or fifteen years after Boulton had sold his first steam engine to a cotton mill, the price of cotton textiles had fallen by 70 percent.

And this created both the first mass market and the first factory—and together modern capitalism and the modern economy altogether.

Neither studies nor market research not computer modeling are a substitute for the test of reality.

Everything improved or new needs, therefore, first to be tested on a small scale, that is, it needs to be piloted.

The way to do this is to find somebody within the enterprise who really wants the new.

As said before, everything new gets into trouble.

And then it needs a champion.

It needs somebody who says, “I am going to make this succeed,” and who then goes to work on it.

And this person needs to be somebody whom the organization respects.

This need not even be somebody within the organization.

A good way to pilot a new product or new service is often to find a customer who really wants the new, and who is willing to work with the producer on making the new product or the new service truly successful.

If the pilot test is successful—if it finds the problems nobody anticipated but also finds the opportunities that nobody anticipated, whether in terms of design, of market, of service—the risk of change is usually quite small.

And it is usually also quite clear where to introduce the change and how to introduce it, that is, what entrepreneurial strategy to employ.”

The ideas of starting simple and market focus need to be explored. Innovation and Entrepreneurship

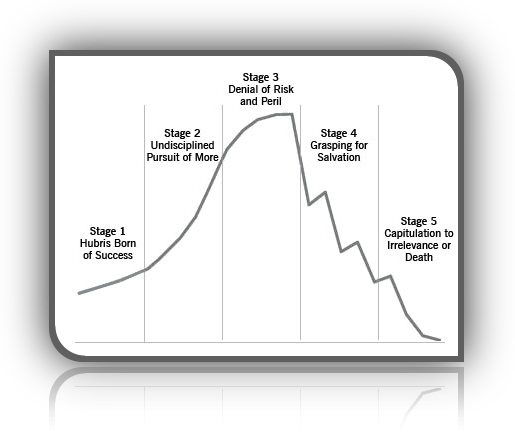

The Failed Strategy

Most of the people who persist in the wilderness leave nothing behind but bleached bones.

When a strategy or an action doesn’t seem to be working, the rule is, “If at first you don’t succeed, try once more. Then do something else.”

The first time around, a new strategy very often doesn’t work.

Then one must sit down and ask what has been learned.

Maybe the service isn’t quite right.

Try to improve it, to change it, and make another major effort.

Maybe, though I am reluctant to encourage this, you might make a third effort.

After that, go to work where the results are.

There is only so much time and so many resources, and there is so much work to be done.

There are exceptions.

You can see some great achievements where people labored in the wilderness for twenty-five years.

But these examples are very rare.

Most of the people who persist in the wilderness leave nothing behind but bleached bones.

There are also true believers who are dedicated to a cause where success, failure, and results are irrelevant, and we need such people.

They are our conscience.

But very few of them achieve.

Maybe their rewards are in Heaven.

But that’s not sure either.

“There is no joy in Heaven over empty churches,” Saint Augustine wrote sixteen hundred years ago to one of his monks who busily built churches all over the desert.

So, if you have no results, try a second time.

Then look at it carefully and move on to something else.

Nov 7 — The Daily Drucker

Theories of the business have to be rethought

Amazon link: The Lean Startup: How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses

What if some one wants to buy you out? What will you do next? In the money or in the game. See Alliances, collaborations below

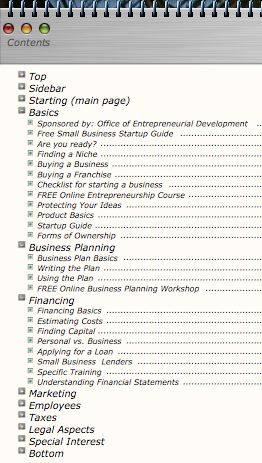

- Foundational awareness

- Realities

- 99% of business plans go unread

- Very small % of patented items are profitable

- Small % of start-ups get VC funding

- Organizationally crowded world: Today's major economic problem is overcapacity in most of the world's industries. Customers are scarce, not products. Demand, not supply, is the problem. Overcapacity leads to hyper competition, with too many goods chasing too few customers. And most goods and services lack differentiation—read more—Philip Kotler.

- Limits of consumer time and money

- Business crisis stories in news (Google News Search: bankruptcy OR layoffs OR downsizing)

- Warren Buffett doesn't invest in Venture Capital situations. Why? Why does he avoid tech companies? (Peter Drucker's observation that tech companies think that customers buy technology rather than what it does for them.)

- Action design resources

- Most basic idea = Always ask "What needs doing?"

- Managing oneself

- Peter's Principles — Inc. Article

- Peter Drucker on Leadership — Forbes Article annotated

- The Daily Drucker (world class planning resource)

- Peter Drucker article on innovation and entrepreneurship

- See Chapter 10 "Making the Future Today" (particularly the part on the power of an idea) in Management, Revised Edition

- Innovation and entrepreneurship (the book)

- Purposeful innovation

- Sources of Innovative Opportunity

- Enterprise or Industry

- Within

- The Unexpected

- The Unexpected Success (find em, run with em)

- Failure

- Event

- Process Needs

- Incongruities

- Changes in Industry & Market Structures

- Outside

- Demographics

- Changes in Perception, Mood, & Meaning

- New Knowledge: scientific/nonscientific

- Bright idea

- Riskiest and least successful

- Principles of innovation (hard core of the discipline)

- Strategies

- Introduce something

- Fustest with the Mostest

- "Hit Them Where They Ain't"

- Creative Imitation

- Entrepreneurial Judo

- Ecological Niches

- Toll-gate

- Specialty skill

- Specialty market

- The strategies that are the innovation

- Changing Values and Characteristics (creating a customer)

- Creating utility

- Pricing is not price

- Adaptation to customer's social & economic reality

- Delivering what represents true value to the customer

- The new venture

- Market focus (very important)

- Financial foresight: cash flow & capital needs ahead

- Building a top management team

- Founding entrepreneur: role, area of work, relationships

- Need for independent, objective, outside advice

- The Entrepreneurial Myth

- Small business management

- Marketing and Innovation in a society moving in time

- Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices Revised Edition. Look for topics below:

- Find: Part I: Management's New Realities

- Find: Theory of the Business

- Find: Making the Future Today

- Find: The Elements of Effective Decision Making

- Find: How to Make People Decisions

- Find: Information Tools and Concepts

- The Knowledge System View

- Five Most Important Questions

- Five deadly business sins

- Alliances, collaborations, outsourcing

- The Art of the Start by Guy Kawasaki (a product driven viewpoint i.e. not market driven)

- Guerrilla Marketing plus other related topics

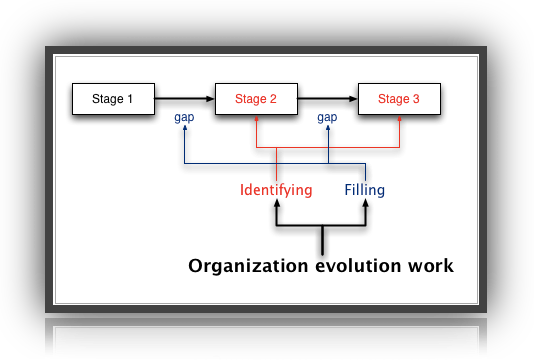

- Organization evolution

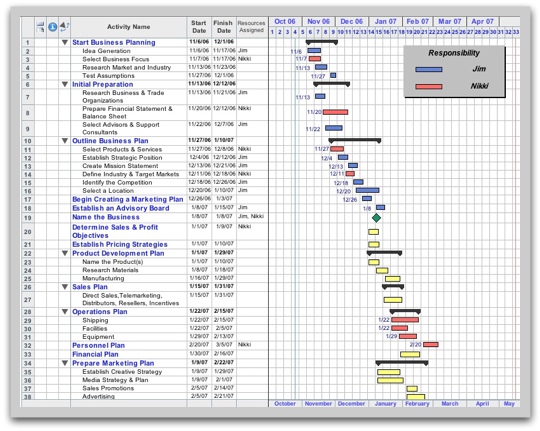

- Calendarizing (the process choreographing action steps)

- Concepts to daily action (a collection of work flow elements for integrating conceptual resources—like the ones introduced on this page— into one's daily action)

- Project planning

- Startup plan development

- SBA resources (see below)

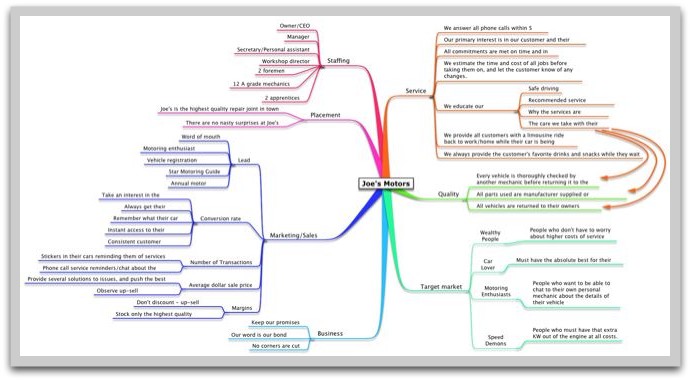

- Startup Thinking Mind Map (below)

- Written plan format and content

- Planning help available

Larger

Take a look at the Forbes 400 wealthiest. Started something, financed it, hung on to their shares, evolved it, didn't become a prisoner of the past, didn't get pushed out by their financial backers …

The Shakeout (calendarize this?)

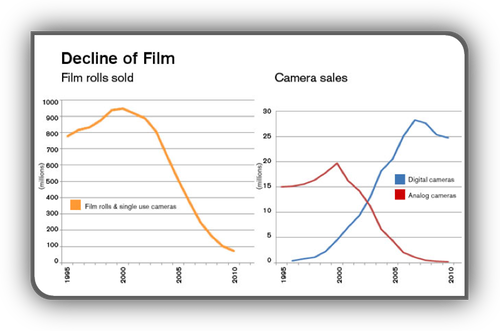

The “shakeout” sets in as soon as the “window” closes.

And the majority of ventures started during the “window” period do not survive the shakeout, as has already been shown for such high-tech industries of yesterday as railroads, electrical apparatus makers, and automobiles.

As these lines are being written, the shakeout has begun among microprocessor, minicomputer, and personal computer companies—only five or six years after the “window” opened.

Today, there are perhaps a hundred companies in the industry in the United States alone.

Ten years hence, by 1995, there are unlikely to be more than a dozen left of any size or significance.

But which ones will survive, which ones will die, and which ones will become permanently crippled—able neither to live nor to die—is unpredictable.

In fact, it is futile to speculate.

Sheer size may ensure survival.

But it does not guarantee success in the shakeout, otherwise Allied Chemical rather than DuPont would today be the world’s biggest and most successful chemical company.

In 1920, when the “window” opened for the chemical industry in the United States, Allied Chemical looked invincible, if only because it had obtained the German chemical patents which the U.S. government had confiscated during World War I.

Seven years later, after the shakeout, Allied Chemical had become a weak also-ran.

It has never been able to regain momentum.

No one in 1949 could have predicted that IBM would emerge as the computer giant, let alone that such big, experienced leaders as G.E. or Siemens would fail completely.

No one in 1910 or 1914 when automobile stocks were the favorites of the New York Stock Exchange could have predicted that General Motors and Ford would survive and prosper and that such universal favorites as Packard or Hupmobile would disappear.

No one in the 1870s and 1880s, the period in which the modern banks were born, could have predicted that Deutsche Bank would swallow up dozens of the old commercial banks of Germany and emerge as the leading bank of the country.

That a certain industry will become important is fairly easy to predict.

There is no case on record where an industry that reached the explosive phase, the “window” phase, as I called it, has then failed to become a major industry.

The question is, Which of the specific units in this industry will be its leaders and so survive?

This rhythm—a period of great excitement during which there is also great speculative ferment, followed by a severe “shakeout”—is particularly pronounced in the high-tech industries.

In the first place, such industries are in the limelight and thus attract far more entrants and far more capital than more mundane areas.

Comments by Warren Buffett.

Also the expectations are much greater.

More people have probably become rich building such prosaic businesses as a shoe-polish or a watchmaking company than have become rich through high-tech businesses.

Yet no one expects shoe-polish makers to build a “billion-dollar business,” nor considers them a failure if all they build is a sound but modest family company.

(Managing the Family Business: see December 28 and 29 in The Daily Drucker)

High tech, by contrast, is a “high-low game,” in which a middle hand is considered worthless.

And this makes high-tech innovation inherently risky.

But also, high tech is not profitable for a very long time.

The world’s computer industry began in 1947-48.

Not until the early 1980s, more than thirty years later, did the industry as a whole reach break-even point.

To be sure, a few companies (practically all of them American, by the way) began to make money much earlier.

And one, IBM, the leader, began to make a great deal of money earlier still.

But across the industry the profits of those few successful computer makers were more than offset by the horrendous losses of the rest; the enormous losses, for instance, which the big international electrical companies took in their abortive attempts to become computer manufacturers.

And exactly the same thing happened in every earlier “high-tech” boom—in the railroad booms of the early nineteenth century, in the electrical apparatus and the automobile booms between 1880 and 1914, in the electric appliance and the radio booms of the 1920s, and so on.

One major reason for this is the need to plow more and more money back into research, technical development, and technical services to stay in the race.

High tech does indeed have to run faster and faster in order to stand still.

This is, of course, part of its fascination.

But it also means that when the shakeout comes, very few businesses in the industry have the financial resources to outlast even a short storm.

This is the reason why high-tech ventures need financial foresight even more than other new ventures, but also the reason why financial foresight is even scarcer among high-tech new ventures than it is among new ventures in general.

(Find “financial foresight” in Innovation and Entrepreneurship and see chapter 3 in The Changing World of the Executive)

There is only one prescription for survival during the shakeout: entrepreneurial management (described in Chapters 12-15).

What distinguished Deutsche Bank from the other “hot” financial institutions of its time was that Georg Siemens thought through and built the world’s first top management team.

What distinguished DuPont from Allied Chemical was that DuPont in the early twenties created the world’s first systematic organization structure, the world’s first long-range planning, and the world’s first system of management information and control.

Allied Chemical, by contrast, was run arbitrarily by one brilliant egomaniac.

But this is not the whole story.

Most of the large companies that failed to survive the more recent computer shakeout — G.E. and Siemens, for instance—are usually considered to have first-rate management.

And the Ford Motor Company survived, though only by the skin of its teeth, even though it was grotesquely mismanaged during the shakeout years.

Entrepreneurial management is thus probably a precondition of survival, but not a guarantee thereof.

And at the time of the shakeout, only insiders (and perhaps not even they) can really know whether a knowledge-based innovator that has grown rapidly for a few boom years is well managed, as DuPont was, or basically unmanaged, as Allied Chemical was.

By the time we do know, it is likely to be too late.

Innovation and Entrepreneurship

SBA resources (very old)

Startup thinking mind map

Full size image

Action timing chart

Amazon.com books: writing business plans: Amazon search for best rated and most popular (familiar mental patterns)

- The One-Page Proposal: How to Get Your Business Pitch onto One Persuasive Page (TOC)

- The One Page Business Plan with CD-ROM (Flyer)

- Amazon.com: Books: Writing a Convincing Business Plan (TOC)

- Amazon.com: Books: Writing Business Plans That Get Results (TOC)

|

![]()