Real Time Management

An erector set for designing your path through time: a heretic’s view

How to guarantee non-performance

I think that working from the (endless) lists approach developed from the flow of events and/or off the top of one’s head is bound to lead to … and eventually serious trouble. It is bound to make you a prisoner of yesterday. It ignores the realities of a changing world — and how it works. Thoughts on brainstorming by Edward de Bono — it is a weak approach and it also ignores strategic realities.

I think Peter Drucker offers better guidance, but it can’t be done overnight — it is a life-long approach without a fixed destination.

BTY he uses the word tasks differently and in different contexts. We are embedded in a knowledge society, a society of organizations and a network society. He saw end results outside of an organization as their justification for existence. He saw three major tasks and three major kinds of work. Tasks: the institution’s performance; making work productive and the worker achieving; managing social impacts and social responsibilities. Work: top management, innovation, and operating. Work is done to accomplish the tasks in two time dimensions — present and future. So there are big tasks, work, worker, and working and these don’t easily integrate — but that ain’t all. Getting beyond my oversimplification which is not designed for individuals — it wasn’t written with YOU (the individual) in mind. You —the individual—is what you need to focused on. You can’t rely on organizations for your future.

Here’s how he used his time to create a (the) world beating reputation.

The purpose of this page is not to offer a complete alternative to GTD, but to bridge the gap.

You can’t work on or draw on things that aren’t on your radar. You can’t navigate to … that are on your radar and the future is not on your radar.

About time

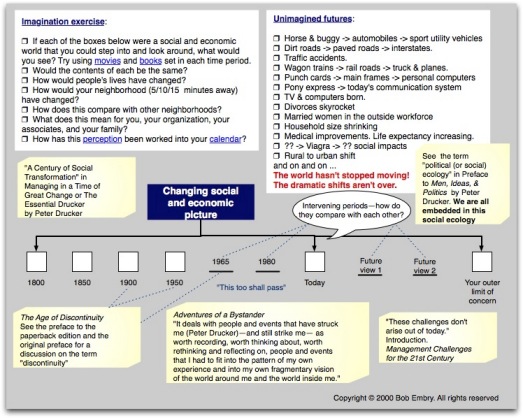

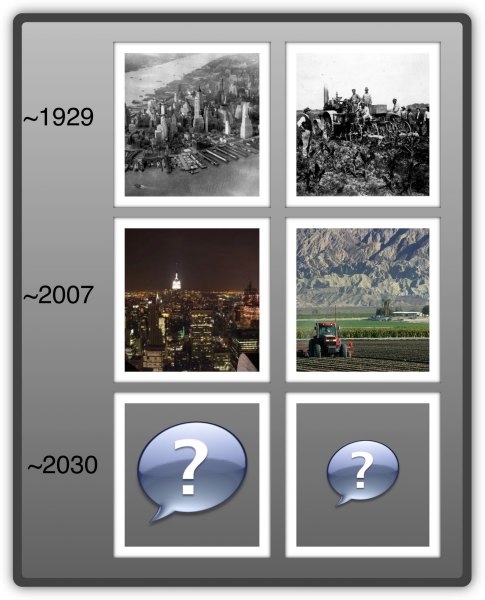

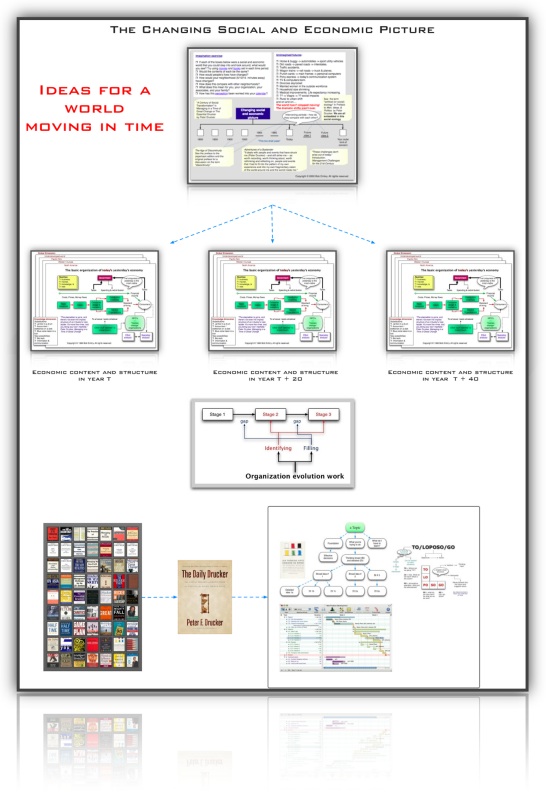

The Changing Social and Economic Picture

The End of Economic Man: The Origins of Totalitarianism (1939)

The Future of Industrial Man (1943)

The New Society: The Anatomy of Industrial Order (1950)

Landmarks of Tomorrow (1957)

The Age of Discontinuity (1968)

Adventures of a Bystander (1978)

The New Realities (1988)

Post-Capitalist Society (1993)

Managing in the Next Society (2002);

Last section originally published earlier in The Economist

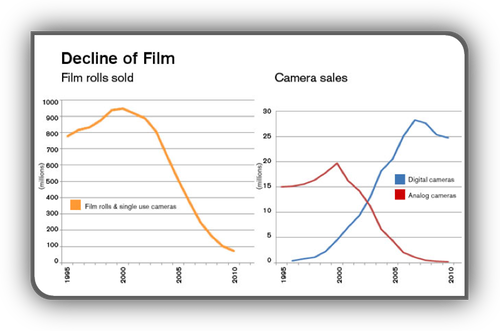

The world is moving away from pre-industrial conditions and the movement is not linear. A tweet is not a linear extrapolation of a telegraph. A smart phone is not a linear extrapolation of a black rotary phone of the 1950s. Industry composition and structures are not static. Apple ™ today is not a linear extrapolation of two guys working out of a garage.

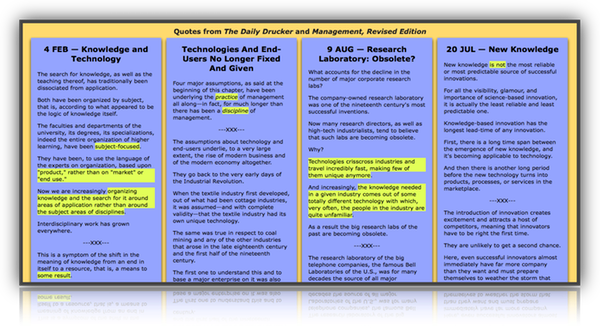

About management

AS WE ADVANCE deeper into the knowledge economy, the basic assumptions underlying much of what is taught and practiced in the name of management are hopelessly out of date. — Management’s New Paradigm

About managing time: chapter 2, “Know thy time” in The Effective Executive

Just getting more done is not productivity. Productivity is the ratio of output to input and in today’s world (an the worldS ahead) it ain’t so simple. Productivity software has nothing to do with this.

The new-productivity challenge

Knowledge: Its Economics and Its Productivity

Larger

Ways to use time:

Managing Oneself Managing Oneself

The conclusion bears repeating: Do not try to change yourself—you are unlikely to succeed. But work hard to improve the way you perform. And try not to take on work you cannot perform or will only perform poorly. — Peter Drucker (calendarize this)

The Effective Executive — a second take The Effective Executive — a second take

The overriding question is “What needs doing?”

The answer to the question “What needs to be done?” almost always contains more than one urgent task.

But effective executives do not splinter themselves.

They concentrate on one task if at all possible.

If they are among those people—a sizable minority—who work best with a change of pace in their working day, they pick two tasks.

I have never encountered an executive who remains effective while tackling more than two tasks at a time.

Hence, after asking what needs to be done, the effective executive sets priorities and sticks to them.

… snip, snip …

Other tasks, no matter how important or appealing, are postponed.

However, after completing the original top-priority task, the executive resets priorities rather than moving on to number two from the original list.

He asks, “What must be done now?”

This generally results in new and different priorities.

“If something fails despite being carefully planned, carefully designed, and conscientiously executed, that failure often bespeaks underlying change and, with it, opportunity.”

— Peter F. Drucker, 1985

How Drucker taught me to focus

Living in More Than One World: How Peter Drucker’s Wisdom Can Inspire Your Life by Bruce Rosenstein Living in More Than One World: How Peter Drucker’s Wisdom Can Inspire Your Life by Bruce Rosenstein

Career and life guidance from Peter Drucker Career and life guidance from Peter Drucker

Building a Non-Competitive Life and Personal Community Building a Non-Competitive Life and Personal Community

Peter Drucker On Leadership Peter Drucker On Leadership

What do you want to be remembered for? What do you want to be remembered for?

Larger

Larger

Career and Life Guidance from Peter Drucker

is attention-directing work

“If something fails despite being carefully planned, carefully designed, and conscientiously executed, that failure often bespeaks underlying change and, with it, opportunity.”

— Peter F. Drucker, 1985

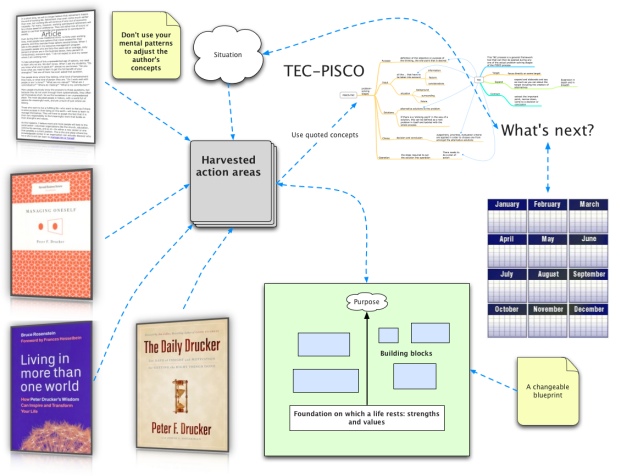

Life-TIME Investment System

Analysis of the entire business and its basic economics always shows it to be in worse disrepair than anyone expected.

The products everyone boasts of turn out to be yesterday’s breadwinners or investments in managerial ego.

Activities to which no one paid much attention turn out to be major cost centers and so expensive as to endanger the competitive position of the company.

What everyone in the business believes to be quality turns out to have little meaning to the customer.

Important and valuable knowledge either is not applied where it could produce results or produces results no one uses.

I know more than one executive who fervently wished at the end of the analysis that he could forget all he had learned and go back to the old days of the “rat race” when “sufficient unto the day was the crisis thereof.”

But precisely because there are so many different areas of importance, the day-by-day method of management is inadequate even in the smallest and simplest business.

Because deterioration is what happens normally—that is, unless somebody counteracts it—there is need for a systematic and purposeful program.

There is need to reduce the almost limitless possible tasks to a manageable number.

There is need to concentrate scarce resources on the greatest opportunities and results.

There is need to do the few right things and do them with excellence.

Managing for Results by Peter Drucker

The 90/10 Rule at Yum! Brands

But every analysis of actual allocation of resources and efforts in business that I have ever seen or made showed clearly that the bulk of time, work, attention, and money first goes to ‘problems’ rather than to opportunities, and, secondly, to areas where even extraordinarily successful performance will have minimal impact on results. (calendarize this?)

One of the hardest things for a manager to remember is that of the 1,000 different situations he or she will be asked to deal with on any given day, only the smallest handful have a shot at moving the enterprise forward in a truly significant way (calendarize this?)

The job of management, then, is to make sure that financial capital, technology, and top talent are deployed where most of the results are and where most of the costs aren’t. The temptation often exists, however, to do exactly the opposite

See chapter 10, The Bright Idea (the riskiest and least successful source of innovative opportunities) in Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Broken Washroom Doors: Drucker said the problem of having people in positions where they do the least amount of good exists everywhere, but it is more rampant in hospitals, churches, and other nonprofits than in corporations.

To raise productivity in most any organization managers should regularly assess their key people, their strengths, and the results they achieve.

Then they should ask themselves:

Do we have the right people in the right jobs, where they can make the greatest contributions?

Are the jobs the right ones, meaning do we have people performing tasks that even if achieved do not add value to the organization?

What changes in people, jobs, and job functions can we make that will yield greater results?

Inside Drucker’s Brain

Competition on the roads ahead

… In the new mental geography created by the railroad, humanity mastered distance. In the mental geography of e-commerce, distance has been eliminated. There is only one economy and only one market.

One consequence of this is that every business must become globally competitive, even if it manufactures or sells only within a local or regional market. The competition is not local anymore—in fact, it knows no boundaries. Every company has to become transnational in the way it is run. Yet the traditional multinational may well become obsolete. It manufactures and distributes in a number of distinct geographies, in which it is a local company. But in e-commerce there are neither local companies nor distinct geographies. Where to manufacture, where to sell, and how to sell will remain important business decisions. But in another twenty years they may no longer determine what a company does, how it does it, and where it does it.

At the same time, it is not yet clear what kinds of goods and services will be bought and sold through e-commerce and what kinds will turn out to be unsuitable for it. This has been true whenever a new distribution channel has arisen. Why, for instance, did the railroad change both the mental and the economic geography of the West, whereas the steamboat—with its equal impact on world trade and passenger traffic—did neither? Why was there no “steamboat boom"?

Equally unclear has been the impact of more recent changes in distribution channels—in the shift, for instance, from the local grocery store to the supermarket, from the individual supermarket to the supermarket chain, and from the supermarket chain to Wal-Mart and other discount chains. It is already clear that the shift to e-commerce will be just as eclectic and unexpected. …

Managing in the Next Society

by Peter Drucker

See Marketing Moves and Chaotics: The Business of Managing and Marketing in the Age of Turbulence

Executive Jobs and Growth

You have to learn to manage in situations where you don’t have command authority, where you are neither controlled nor controlling. That is the fundamental change. Management textbooks still talk mainly about managing subordinates. But you no longer evaluate an executive in terms of how many people report to him or her. That standard doesn’t mean as much as the complexity of the job, the information it uses and generates, and the different kinds of relationships needed to do the work.

Similarly, business news still refers to managing subsidiaries. But this is the control approach of the 1950s or 1960s. The reality is that the multinational corporation is rapidly becoming an endangered species. Businesses used to grow in one of two ways: from grass-roots up or by acquisition. In both cases, the manager had control. Today businesses grow through alliances, all kinds of dangerous liaisons and joint ventures, which, by the way, very few people understand. This new type of growth upsets the traditional manager, who believes he or she must own or control sources and markets.

Be prepared …

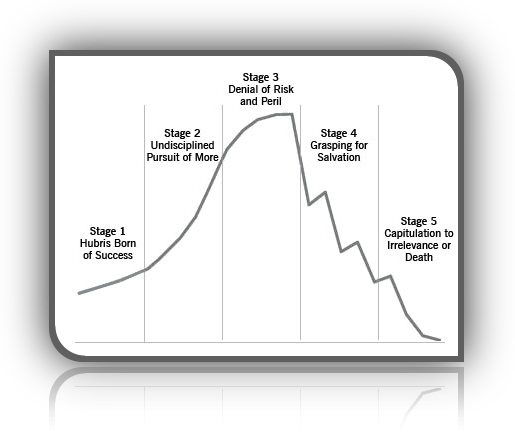

The Shakeout (calendarize this?)

The “shakeout” sets in as soon as the “window” closes.

And the majority of ventures started during the “window” period do not survive the shakeout, as has already been shown for such high-tech industries of yesterday as railroads, electrical apparatus makers, and automobiles.

As these lines are being written, the shakeout has begun among microprocessor, minicomputer, and personal computer companies—only five or six years after the “window” opened.

Today, there are perhaps a hundred companies in the industry in the United States alone.

Ten years hence, by 1995, there are unlikely to be more than a dozen left of any size or significance.

But which ones will survive, which ones will die, and which ones will become permanently crippled—able neither to live nor to die—is unpredictable.

In fact, it is futile to speculate.

Sheer size may ensure survival.

But it does not guarantee success in the shakeout, otherwise Allied Chemical rather than DuPont would today be the world’s biggest and most successful chemical company.

In 1920, when the “window” opened for the chemical industry in the United States, Allied Chemical looked invincible, if only because it had obtained the German chemical patents which the U.S. government had confiscated during World War I.

Seven years later, after the shakeout, Allied Chemical had become a weak also-ran.

It has never been able to regain momentum.

No one in 1949 could have predicted that IBM would emerge as the computer giant, let alone that such big, experienced leaders as G.E. or Siemens would fail completely.

No one in 1910 or 1914 when automobile stocks were the favorites of the New York Stock Exchange could have predicted that General Motors and Ford would survive and prosper and that such universal favorites as Packard or Hupmobile would disappear.

No one in the 1870s and 1880s, the period in which the modern banks were born, could have predicted that Deutsche Bank would swallow up dozens of the old commercial banks of Germany and emerge as the leading bank of the country.

That a certain industry will become important is fairly easy to predict.

There is no case on record where an industry that reached the explosive phase, the “window” phase, as I called it, has then failed to become a major industry.

The question is, Which of the specific units in this industry will be its leaders and so survive?

This rhythm—a period of great excitement during which there is also great speculative ferment, followed by a severe “shakeout”—is particularly pronounced in the high-tech industries.

In the first place, such industries are in the limelight and thus attract far more entrants and far more capital than more mundane areas.

Comments by Warren Buffett.

Also the expectations are much greater.

More people have probably become rich building such prosaic businesses as a shoe-polish or a watchmaking company than have become rich through high-tech businesses.

Yet no one expects shoe-polish makers to build a “billion-dollar business,” nor considers them a failure if all they build is a sound but modest family company.

(Managing the Family Business: see December 28 and 29 in The Daily Drucker)

High tech, by contrast, is a “high-low game,” in which a middle hand is considered worthless.

And this makes high-tech innovation inherently risky.

But also, high tech is not profitable for a very long time.

The world’s computer industry began in 1947-48.

Not until the early 1980s, more than thirty years later, did the industry as a whole reach break-even point.

To be sure, a few companies (practically all of them American, by the way) began to make money much earlier.

And one, IBM, the leader, began to make a great deal of money earlier still.

But across the industry the profits of those few successful computer makers were more than offset by the horrendous losses of the rest; the enormous losses, for instance, which the big international electrical companies took in their abortive attempts to become computer manufacturers.

And exactly the same thing happened in every earlier “high-tech” boom—in the railroad booms of the early nineteenth century, in the electrical apparatus and the automobile booms between 1880 and 1914, in the electric appliance and the radio booms of the 1920s, and so on.

One major reason for this is the need to plow more and more money back into research, technical development, and technical services to stay in the race.

High tech does indeed have to run faster and faster in order to stand still.

This is, of course, part of its fascination.

But it also means that when the shakeout comes, very few businesses in the industry have the financial resources to outlast even a short storm.

This is the reason why high-tech ventures need financial foresight even more than other new ventures, but also the reason why financial foresight is even scarcer among high-tech new ventures than it is among new ventures in general.

(Find “financial foresight” in Innovation and Entrepreneurship and see chapter 3 in The Changing World of the Executive)

There is only one prescription for survival during the shakeout: entrepreneurial management (described in Chapters 12-15).

What distinguished Deutsche Bank from the other “hot” financial institutions of its time was that Georg Siemens thought through and built the world’s first top management team.

What distinguished DuPont from Allied Chemical was that DuPont in the early twenties created the world’s first systematic organization structure, the world’s first long-range planning, and the world’s first system of management information and control.

Allied Chemical, by contrast, was run arbitrarily by one brilliant egomaniac.

But this is not the whole story.

Most of the large companies that failed to survive the more recent computer shakeout — G.E. and Siemens, for instance—are usually considered to have first-rate management.

And the Ford Motor Company survived, though only by the skin of its teeth, even though it was grotesquely mismanaged during the shakeout years.

Entrepreneurial management is thus probably a precondition of survival, but not a guarantee thereof.

And at the time of the shakeout, only insiders (and perhaps not even they) can really know whether a knowledge-based innovator that has grown rapidly for a few boom years is well managed, as DuPont was, or basically unmanaged, as Allied Chemical was.

By the time we do know, it is likely to be too late.

Innovation and Entrepreneurship

NBC Universal’s Jeff Zucker says he’s being shown the door

Comcast’s Steve Burke told him to ‘move on’ after the merger.

Jeff Zucker, a lifelong employee of NBC Universal, said Friday that he would step down as chief executive after being told there won’t be a place for him once Philadelphia cable giant Comcast Corp. takes over the company at the end of the year.

Now, for the rest of the story …

Soros to return outsiders’ hedge fund money

(Reuters)—Billionaire investor George Soros, whose stock-picking career has spanned nearly four decades, said he will manage money only for himself and his family as new regulations threaten to crimp the hedge fund industry he made famous.

The octogenarian fund manager, known as much for earning $1 billion on a nervy currency bet as for giving away millions to support liberal causes, will return roughly $1 billion to outside investors most likely by the end of the year and turn Soros Fund Management into a family office. The sum represents only a small portion of the $25 billion he oversees.

Keith Anderson, who has been Soros’ chief investment officer since 2008, will leave the firm.

Now, for the rest of the story …

Soros hires new chief investment officer

(Reuters)—Billionaire investor George Soros is continuing to overhaul the management team of his Soros Fund Management LLC, which is converting from a hedge fund to a family office.

The octogenarian fund manager, who is in the process of returning $1 billion to outside investors, announced in a September 19 letter that Scott Bessent is joining as the firm’s new chief investment officer.

Bessent, a former Soros fund alum, most recently was a senior partner and director of research for Protege Partners. He will takeover for Keith Anderson, who stepped down as the fund’s chief investment officer in July.

Now, for the rest of the story …

Be prepared

List of topics in this Folder

TLN Keywords: tlnkwtimemanagement

|

![]()

![]()