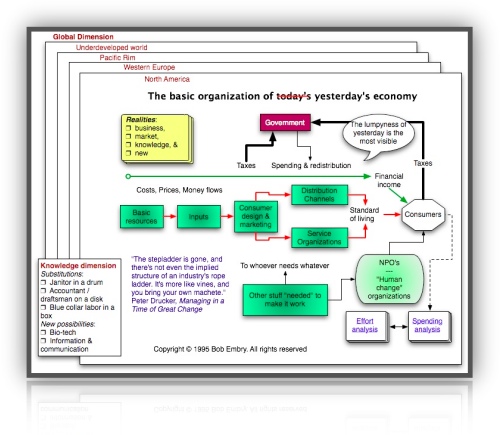

Society of organizations, management, true marketing and individual roles

The knowledge society into which we are moving so fast is going to be a society of organizations.

But of organizations—plural—that will be diverse, decentralized, multiform.

And within these organizations, we are moving away from the standardized, uniform structures that were generally accepted in public administration and business management, “the one right structure for the typical manufacturing company,” for instance, or the “model government agency.”

We are moving toward organic design, informed by mission, purpose, strategy, and the environment, both social and physical—the design I began to advocate forty years ago in The Practice of Management (which came out in 1954). … — Adventures of a Bystander

Larger

From Analysis to Perception — The New Worldview

“Small is beautiful” is, of course, as much stifling dogma as “big is best”—and equally stupid, as one look at the diversity of God’s creation will show. — Adventures of a Bystander

The Function Of Organizations

The function of organizations is to make knowledges productive. Organizations have become central to society in all developed countries because of the shift from knowledge to knowledges.

The more specialized knowledges are, the more effective they will be. The best radiologists are not the ones who know the most about medicine; they are the specialists who know how to obtain images of the body's inside through X-ray, ultrasound, body scanner, magnetic resonance. The best market researchers are not those who know the most about business, but the ones who know the most about market research. Yet neither radiologists nor market researchers achieve results by themselves; their work is “input” only. It does not become results unless put together with the work of other specialists.

Knowledges by themselves are sterile. They become productive only if welded together into a single, unified knowledge. To make this possible is the task of organization, the reason for its existence, its function.

Peter Drucker, Post-Capitalist Society

In the knowledge society, it is not the individual who performs.

The individual is a cost center rather than a performance center.

It is the organization that performs. (Across multiple time dimensions: explore the life stories of HP, Kodak, RIM or RCA) — A Century of Social Transformation by Peter Drucker

Larger

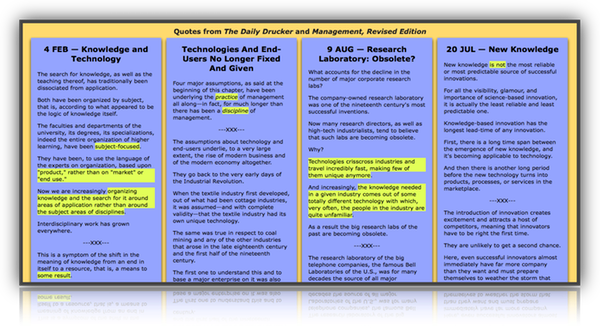

It is the very nature of knowledge

that it changes fast and

that today's certainties

will be tomorrow's absurdities. — Peter Drucker

Because the knowledge society

perforce has to be

a society of organizations,

its central and distinctive organ is

management.

When we first began to talk of management, the term meant “business management” — since large-scale business was the first of the new organizations to become visible.

But we have learned this last half-century that management is the distinctive organ of all organizations.

All of them require management—whether they use the term or not.

All managers do the same things whatever the business of their organization.

All of them have to bring people—each of them possessing a different knowledge—together for joint performance.

All of them have to make human strengths productive in performance and human weaknesses irrelevant.

All of them have to think through what are “results” in the organization—and have then to define objectives.

Management by Objectives — a user's guide

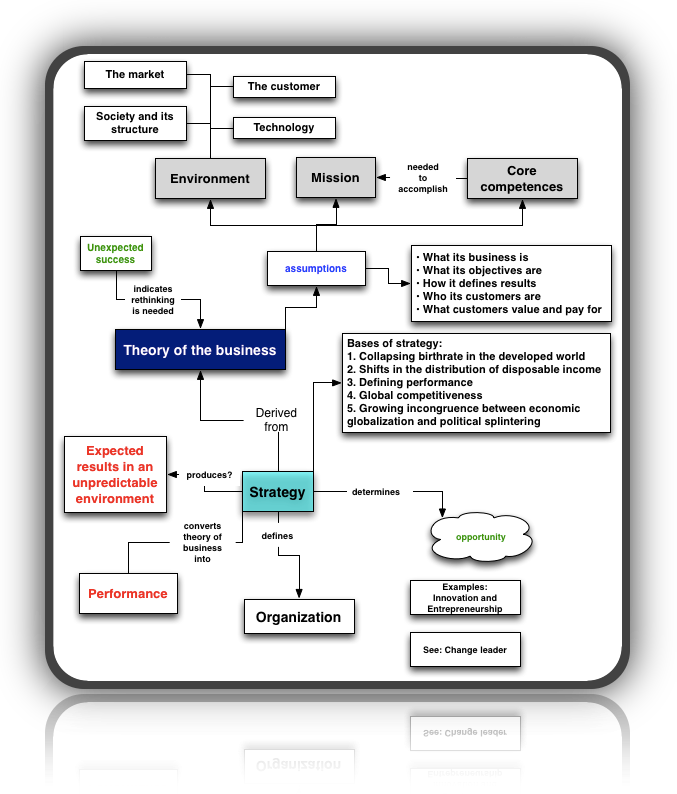

All of them are responsible to think through what I call the “theory of the business,” that is, the assumptions on which the organization bases its performance and actions, and equally, the assumptions which organizations make to decide what things not to do.

Communicate and Test Assumptions

The theory of the business must be known and understood throughout the organization.

This is easy in an organization’s early days.

But as it becomes successful, an organization tends increasingly to take its theory for granted, becoming less and less conscious of it.

Then the organization becomes sloppy.

It begins to cut corners.

It begins to pursue what is expedient rather than what is right.

It stops thinking.

It stops questioning.

It remembers the answers but has forgotten the questions.

The theory of the business becomes “culture.”

But culture is no substitute for discipline, and the theory of the business is a discipline.

The theory of the business has to be tested constantly.

It is not graven on tablets of stone.

It is a hypothesis.

And it is a hypothesis about things that are in constant flux—society, markets, customers, technology.

And so, built into the theory of the business must be the ability to change itself.

Some theories are so powerful that they last for a long time.

Eventually every theory becomes obsolete and then invalid.

It happened to the GMs and the AT&Ts.

It happened to IBM.

It is also happening to the rapidly unraveling Japanese keiretsu.

4 JUL The Daily Drucker

All of them require an organ that thinks through strategies, that is, the means through which the goals of the organization become performance.

All of them have to define the values of the organization, its system of rewards and punishments, and with its spirit and its culture.

In all of them, managers need both

the knowledge of management as work and discipline,

and

the knowledge and understanding of the organization itself

its purposes,

its values,

its environment and markets,

its core competencies.

— A Century of Social Transformation by Peter Drucker

Purpose and Objectives First

To Drucker, strategy, like everything else in management, is a thinking person’s game.

It isn’t arrived at by following some rigid set of rules but by thinking through various aspects of the business.

It all starts with objectives.

Management by Objectives — a user's guide

“Only a clear definition of the mission makes possible clear and realistic business objectives.

It is the foundation for priorities, strategies, plans and work assignments.

It is the starting point for the design of managerial jobs, and, above all, for the design of managerial structures.

Structure follows strategy.

Strategy determines what the key activities are in a given business.

And strategy requires knowing what our business is and what it should be.”

Drucker also explained that “nothing may seem simpler or more obvious than to answer what a company’s business is.

A steel mill makes steel, a railroad runs to carry freight and passengers … .

Actually ‘what is our business?’ is almost always a difficult question which can be answered only after hard thinking and studying.

And the right answer is usually anything but obvious.”

Thinking back to Drucker’s Law, no strategy can be created without the customer, for it is the customer who defines business purpose.

And “therefore the question ‘what is our business?’ can be answered only by looking at the business from the outside, from the point of view of the customer and the market.

What the customer sees, thinks, believes and wants at any given time must be accepted by management as an objective fact deserving to be taken as seriously” as any hard data collected from salespeople, accountants, or engineers, contended Drucker.

Drucker claimed that the single most important cause of business failure can be attributed to management’s failure to ask the question “what is our business?” in a “clear and sharp form.”

And it isn’t only when a company is starting out that the question should be asked, or when the company is in trouble.

“On the contrary,” Drucker wrote, “to raise the question and to study it thoroughly is most needed when a business is successful.

For then failure to raise it may result in rapid decline.”

— Inside Drucker's Brain

A product or service name is never an effective answer to these questions because it doesn’t specify the specific contribution to the customer that matches what customers value and pay for — they buy what it does for them. See “The Customer: Joined at the Hip” in The Definitive Drucker and “Changing Values and Characteristics (creating a customer)” in Innovation and Entrepreneurship — bobembry

The view of management presented above is the opposite of inside-out behavior …

AS WE ADVANCE deeper into the knowledge economy, the basic assumptions underlying much of what is taught and practiced in the name of management are hopelessly out of date. (calendarize this?)

Amazon link: How The Mighty Fall

Only the Paranoid Survive

… the organization of the post-capitalist society of organizations

is a destabilizer.

Because its function is to put knowledge to work

—on tools, processes, and products;

on work;

on knowledge itself—

it must be organized for constant change.

It must be organized for innovation;

and innovation,

as the Austro-American economist

Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950) said,

is “creative destruction.”

It must be organized for systematic abandonment

of the established, the customary, the familiar,

the comfortable

— whether products, services, and processes,

human and social relationships, skills,

or organizations themselves.

It is the very nature of knowledge

that it changes fast and

that today's certainties

will be tomorrow's absurdities. — Peter Drucker

Changing Values and Characteristics

From chapter 19 of Innovation and Entrepreneurship by Peter Drucker

Amazon link: Innovation and Entrepreneurship

In the entrepreneurial strategies discussed so far, the aim is to introduce an innovation.

In the entrepreneurial strategy discussed in this chapter, the strategy itself is the innovation.

The product or service it carries may well have been around a long time—in our first example, the postal service, it was almost two thousand years old.

But the strategy converts this old, established product or service into something new.

It changes its utility, its value, its economic characteristics.

While physically there is no change, economically there is something different and new.

All the strategies to be discussed in this chapter have one thing in common.

They create a customer — and that is the ultimate purpose of a business, indeed, of economic activity.

As was first said more than thirty years ago in my The Practice of Management (New York: Harper & Row, 1954).

But they do so in four different ways:

by creating utility by creating utility

by pricing by pricing

by adaptation to the customer’s social and economic reality by adaptation to the customer’s social and economic reality

by delivering what represents true value to the customer by delivering what represents true value to the customer

... snip, snip ...

These examples are likely to be considered obvious.

Surely, anybody applying a little intelligence would have come up with these and similar strategies?

But the father of systematic economics, David Ricardo, is believed to have said once, “Profits are not made by differential cleverness, but by differential stupidity.”

The strategies work, not because they are clever, but because most suppliers—of goods as well as of services, businesses as well as public-service institutions—do not think.

They work precisely because they are so “obvious.”

Why, then, are they so rare?

For, as these examples show, anyone who asks the question, What does the customer really buy? will win the race.

In fact, it is not even a race since nobody else is running.

What explains this?

One reason is the economists and their concept of “value.”

Every economics book points out that customers do not buy a “product,” but what the product does for them.

And then, every economics book promptly drops consideration of everything except the “price” for the product, a “price” defined as what the customer pays to take possession or ownership of a thing or a service.

What the product does for the customer is never mentioned again.

Unfortunately, suppliers, whether of products or of services, tend to follow the economists.

It is meaningful to say that “product A costs X dollars.”

It is meaningful to say that “we have to get Y dollars for the product to cover our own costs of production and have enough left over to cover the cost of capital, and thereby to show an adequate profit.”

But it makes no sense at all to conclude and therefore the customer has to pay the lump sum of Y dollars in cash for each piece of product A he buys.”

Rather, the argument should go as follows: “What the customer pays for each piece of the product has to work out as Y dollars for us.

But how the customer pays depends on what makes the most sense to him.

It depends on what the product does for the customer.

It depends on what fits his reality.

It depends on what the customer sees as ‘value.’”

Price in itself is not “pricing,” and it is not “value.”

It was this insight that gave King Gillette a virtual monopoly on the shaving market for almost forty years; it also enabled the tiny Haloid Company to become the multibillion-dollar Xerox Company in ten years, and it gave General Electric world leadership in steam turbines.

In every single case, these companies became exceedingly profitable.

But they earned their profitability.

They were paid for giving their customers satisfaction, for giving their customers what the customers wanted to buy, in other words, for giving their customers their money’s worth.

“But this is nothing but elementary marketing,” most readers will protest, and they are right.

It is nothing but elementary marketing.

To start out with the customer’s utility, with what the customer buys, with what the realities of the customer are and what the customer’s values are—this is what marketing is all about.

But why, after forty years of preaching Marketing, teaching Marketing, professing Marketing, so few suppliers are willing to follow, I cannot explain.

The fact remains that so far, anyone who is willing to use marketing as the basis for strategy is likely to acquire leadership in an industry or a market fast and almost without risk.

Entrepreneurial strategies are as important as purposeful innovation and entrepreneurial management.

Together, the three make up innovation and entrepreneurship.

The available strategies are reasonably clear, and there are only a few of them.

But it is far less easy to be specific about entrepreneurial strategies than it is about purposeful innovation and entrepreneurial management.

We know what the areas are in which innovative opportunities are to be found and how they are to be analyzed.

There are correct policies and practices and wrong policies and practices to make an existing business or public-service institution capable of entrepreneurship; right things to do and wrong things to do in a new venture.

But the entrepreneurial strategy that fits a certain innovation is a high-risk decision.

Some entrepreneurial strategies are better fits in a given situation, for example, the strategy that I called entrepreneurial judo, which is the strategy of choice where the leading businesses in an industry persist year in and year out in the same habits of arrogance and false superiority.

We can describe the typical advantages and the typical limitations of certain entrepreneurial strategies.

Above all, we know that an entrepreneurial strategy has more chance of success the more it starts out with the users—their utilities, their values, their realities.

An innovation is a change in market or society.

It produces a greater yield for the user, greater wealth-producing capacity for society, higher value or greater satisfaction.

The test of an innovation is always what it does for the user.

Hence, entrepreneurship always needs to be market-focused, indeed, market-driven.

Still, entrepreneurial strategy remains the decision-making area of entrepreneurship and therefore the risk-taking one.

It is by no means hunch or gamble.

But it also is not precisely science.

Rather, it is judgment.

What do customers value?

The question, What do customers value?—what satisfies their needs, wants, and aspirations—is so complicated that it can only be answered by customers themselves.

And the first rule is that there are no irrational customers.

Almost without exception, customers behave rationally in terms of their own realities and their own situation. (Their logic bubble — see below)

Leadership should not even try to guess at the answers but should always go to the customers in a systematic quest for those answers.

I practice this.

Each year I personally telephone a random sample of fifty or sixty students who graduated ten years earlier.

I ask, “Looking back, what did we contribute in this school?

What is still important to you?

What should we do better?

What should we stop doing?”

And believe me, the knowledge I have gained has had a profound influence.

What does the customer value? may be the most important question.

Yet it is the one least often asked.

Nonprofit leaders tend to answer it for themselves.

“It’s the quality of our programs.

It’s the way we improve the community.”

People are so convinced they are doing the right things and so committed to their cause that they come to see the institution as an end in itself.

But that’s a bureaucracy.

Instead of asking, “Does it deliver value to our customers?” they ask, “Does it fit our rules?”

And that not only inhibits performance but also destroys vision and dedication.

— Peter Drucker,

The Five Most Important Questions …

Quality

Quality in a product or service is not what the supplier puts in.

It is what the customer gets out and is willing to pay for.

A product is not quality because it is hard to make and costs a lot of money, as manufacturers typically believe.

This is incompetence.

Customers pay only for what is of use to them and gives them value.

Nothing else constitutes quality.

— Peter Drucker

The Logic Bubble

I (Edward de Bono) created the term ‘logic bubble’ in a previous book.

When someone does something you do not like or with which you do not agree, it is easy to label that person as stupid, ignorant or malevolent.

But that person may be acting ‘logically’ within his or her ‘logic bubble’.

That bubble is made up of the perceptions, values, needs and experience of that person.

If you make a real effort to see inside that bubble and to see where that person is ‘coming from’, you usually see the logic of that person’s position.

In the school programme for teaching thinking (CoRT (Cognitive Research Trust) programme) there are tools which broaden perception so the thinker sees a wider picture and acts accordingly.

One of these tools is OPV, which encourages the thinker to ‘see the Other Person’s Point of View’.

We have numerous examples where a serious fight came to a sudden end when the combatants (who had learned the methods) decided to do an OPV on each other, a very similar process to understanding the ‘logic bubble’ of the other party.

— Edward de Bono

Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything (P.S.)

Communications

The society of organizations demands of the individual decisions regarding himself.

At first sight, the decision may appear only to concern career and livelihood.

“What shall I do?” is the form in which the question is usually asked.

But actually it reflects a demand that the individual take responsibility for society and its institutions.

“What cause do I want to serve?” is implied.

The World is Full of Options The World is Full of Options

Carefully choosing your nonprofit affiliations (beware of scams and inside-out bureaucracies because society suffers the consequences and you are part of society. Carefully choosing your nonprofit affiliations (beware of scams and inside-out bureaucracies because society suffers the consequences and you are part of society.

If they don’t produce the desired results outside of themselves then we have to pay a second or a third or a fourth … organization until we get what is needed.)

And underlying this question is the demand the individual take responsibility for himself.

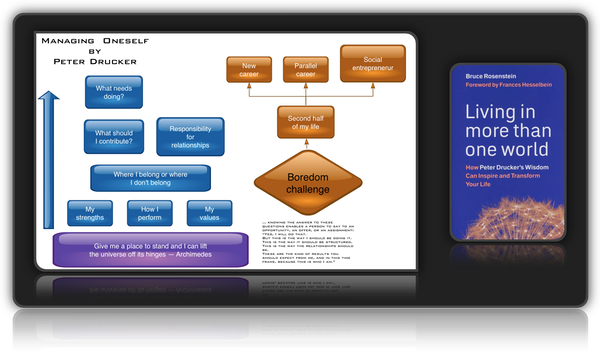

Managing Oneself then … Managing Oneself then …

The Effective Executive: Preface The Effective Executive: Preface

“What shall I do with myself?” rather than “’What shall I do?” is really being asked of the young by the multitude of choices around them.

The society of organizations forces the individual to ask of himself:

“Who am I?” “Who am I?”

“What do I want to be?” “What do I want to be?”

“What do I want to put into life and what do I want to get out of it?” “What do I want to put into life and what do I want to get out of it?”

read more on how can the individual survive …

The Age of Discontinuity:

Guidelines To Our Changing Society

enhanced by bobembry

... replace the quest for success with the quest for contribution.

(to the society of organizations moving in time — above)

The critical question is not, “How can I achieve?”

but “What can I contribute?”

The Daily Drucker

You can’t design your life around a temporary organization

Successful careers are not planned

They develop when people are prepared

for opportunities

because they know

their strengths,

their method of work, and

their values.

Knowing where one belongs

can transform an ordinary person

—hardworking and competent but otherwise mediocre—

into an outstanding performer.

Larger

Managing Oneself and Living in More than One World

To get the benefits you have to calendarize these

“What do you need to learn to get the most out of your strengths?”

The World is Full of Options

“What do you need to learn so that you can decide where to go next?”

Managing in a Time of Great Change

The three types of intelligence discussed in The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli

Types of behavior that can be observed …

… “Power has to be used.

It is a reality.

If the decent and idealistic toss power in the gutter, the guttersnipes pick it up.

If the able and educated refuse to exercise power responsibly, irresponsible and incompetent people take over the seats of the mighty and the levers of power.

Power not being used for social purposes passes to people who use it for their own ends.

At best it is taken over by the careerists who are led by their own timidity into becoming arbitrary, autocratic, and bureaucratic.”

— How Can The Individual Survive?

The Age of Discontinuity: Guidelines To Our Changing Society

by Peter Drucker

What do you want to be remembered for?

In Landmarks of Tomorrow, Peter Drucker wrote “everyone is an understudy to the leading role in the drama of human destiny” and the “great roles are not written in the iambic pentameter or the Alexandrine of the heroic theater.”

They are, instead, “prosaic — played out in one’s daily life, in one’s work, in one’s citizenship, in one’s compassion or lack of it, in one’s courage to stick on an unpopular principle, and in one’s refusal to sanction man’s inhumanity to man in an age of cruelty and moral numbness.”

Keywords:

|

![]()