Parallel Thinking

By Edward de Bono (includes links to many of his other books)

Amazon link

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases

About the Book

Western thinking is failing because it was not designed to deal with change.

In this provocative masterpiece of creative thinking, Edward de Bono argues for a game-changing new way to think.

For thousands of years we have followed the thinking system designed by the Greek philosophers Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, based on analysis and argument.

But if we are to flourish in today’s rapidly changing world we need to free our minds of these ‘Doxes’ and embrace a more flexible and nimble model.

This book is not about philosophy; it is about the practical (and parallel) thinking required to get things done in an ever-changing world.

Note the areas where judgement is mentioned ↓

19 The Tyranny Of Judgement

‘Does your grandmother like carrots?’ ‘Yes.’

‘Does your grandmother like marrows?’

‘Yes.’

‘Does your grandmother like peas?’

‘No.’

‘Does your grandmother like tomatoes?’ ‘No.’

‘Does your grandmother like lettuce?’ ‘Yes.’

So what vegetables does the grandmother like?

That is a well-known children’s game in which one person has to deduce the ‘principle’ on which the grandmother likes certain vegetables but not others.

Here there is a ‘true’ principle to be discovered precisely because it has been put there (a matter of ‘game truth’).

Who has put there the principle that the three angles of a triangle always add up to two right angles?

The answer is that the action of putting together three lines to make a triangle has the inevitable consequence that the angles add up to two right angles.

There are undoubtedly some ‘inner truths’.

Usually these are ‘organizing principles’.

It was the contribution of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle to take the truth that there might be some inner truths in certain instances and to extend this to all matters.

This is a totally unjustified extrapolation and is simply a ‘belief truth’ itself.

It is as much a religion as any other religion that depends on belief truth.

The result is that clusterings of convenience come to be treated as ‘true definitions’ simply because no one around has the wit to refute them.

Induction may reveal ‘inner truths’ as in the grandmother example given above, where a number of instances can lead you to guess the principle being used.

But in most cases induction is no more than a shorthand summary of past experience.

There is a very close relationship between ‘truth’, ‘true definitions’ (boxes, categories, etc.) and judgement.

All three go tightly together to give us our traditional thinking system.

The Socratic method really refers to the discovery or setting up of the ‘true definitions’, but in practice we can extend it to the judgement of whether something fits a definition, because this is partly how Socrates set up the definitions in the first place.

Hunting for game birds is taken very seriously in the English countryside.

The novice who is taken shooting for the first time is hugely embarrassed to find that he has shot at a blackbird in the mistaken belief that it was a pheasant.

The humiliation is extreme.

Towards the end of the season the hunter is equally embarrassed at shooting down a high-flying hen pheasant when ‘cocks only’ has been ordained by the gamekeeper.

So with time and effort the hunters become very skilled at recognizing each bird.

If the recognition is exact then the action follows automatically.

Is that a pheasant?

Yes, it is a pheasant.

Bang!

A doctor learns the disease ‘boxes’ in medical school.

He or she learns how to look for symptoms by direct examination or through tests (X-rays, blood tests, etc.) and learns how to come to a conclusion or make a judgement.

Once the judgement has been made then the treatment is quite easy, because it is more or less automatic or standardized.

So judgement and ‘boxes’ are the link between circumstance and appropriate action.

If something is poisonous you do not eat it.

If someone is dishonest you watch that person carefully.

If a government is not democratic you condemn it.

So the thinking operation is

1. Set up the boxes.

2. Regard them as ‘true’ or ‘absolute’.

3. Judge something into a box.

4. Take the action indicated by the box.

The method simplifies life and seems to work.

It has always been the basis of our education, the basis of our thinking, the basis of our behavior.

Judgement is used to validate the definition and to reject the ‘untrue’, as discussed in a previous section.

Judgement is then used in ‘recognition’ and to pop things into the established boxes.

It is this last aspect of judgement which concerns me here.

I am not impressed by the argument that in its purest form the system works because ‘inner truth’ is restricted to a very few areas and because the ‘boxes’ are designed very carefully to take the system into account.

I am sure that this is occasionally true.

But we have to look at the practical aspect of the method, where people make category judgements and dangerous generalizations.

The question is whether it is really feasible to hope that people can be thoroughly educated to use the system in its purest sense or whether the system itself is so open to poor use that we had better change the system.l can only say, from my experience, that some of those who claim to be the teachers of the best way to use the critical system are themselves every bit as guilty of its poor use as anyone else.

This suggests that the system is at fault.

In most cases induction is no more than a shorthand summary of past experience.

One of the major limitations of the judgement system is that it is reactive rather than proactive.

This means that you criticize ideas rather than create them.

The generative capacity is very low.

It is restricted to thesis/antithesis/synthesis, which is only a tiny fraction of the creative potential in any situation.

I shall deal with this aspect in a later section; what concerns me here is the ‘judgement’ that puts things into the waiting boxes.

The waiting boxes are standard, fixed and stereotyped.

This means that we see things in a somewhat rigid and fixed way.

While this may make for convenience, it does not make for the most appropriate action.

The element of exploration is very restricted.

It is restricted to which boxes are relevant and which of these is to be used.

Complex situations are oversimplified and forced into standard boxes which simply ignore certain factors.

We are forced to look at the world with the perceptions, concepts and language which were set down in previous times.

Our experience has been frozen, fixed and fossilized into existing boxes.

Yet there is an absolute mathematical need to change these boxes.

We cannot do this, because as soon as we step outside the established boxes then the traditionalists point out the error.

So the traditional thinking method is excellent at defending and preserving its inadequacies — because it claims to have set the rules of the game: use these standard boxes.

People are forced to use the judgement/ box system because education has not developed and has not taught the exploration/design system.

The classification habits of psychologists, especially in the USA, are a clear example of this traditional habit.

Suppose you ‘judge’ people into different categories or boxes.

What does that mean?

Does it mean that you are not going to employ her because she is ‘right-brain’?

Does it mean that you do not put him into research because he is an ‘adaptor’ rather than an ‘innovator’?

Very quickly this becomes a dangerous form of intellectual racism.l am sure that the original developers of the tests used did not see them as discriminating devices and did not feel that ‘action’ should follow the judgement.

I am sure they regarded them only as ‘another factor’ in carrying out an exploration of a person’s capabilities.

Even then - I am not too happy, because such tests are based on ‘what is’ rather than ‘what can be’.

Should we test a person’s thinking ability or should we design methods which will increase that ability considerably?

I am much afraid that we are still too hung up on that ‘inner-truth’ belief which is more interested in what is there than in what can be put there.

In school we are always asking students to judge, to categorize, to analyze and to dissect.

There is far less emphasis on exploration, possibility, generation, creativity and design.

There is more emphasis on what things are than on what you can make things be.

This false emphasis arises directly from the Socratic notion that knowledge is virtue.

If you have knowledge then action is easy.

We pay much attention to literacy and numeracy but not to ‘operacy’.

This is a word invented many years ago to indicate the ‘skills of action’.

Design is a key aspect of operacy.

‘How do we design a way forward?’

People are forced to use the judgement/ box system because education has not developed and has not taught the exploration/design system.

21 Exploration vs. Judgement

‘I think that house is Georgian.’

‘It cannot be Georgian the windows are all wrong.’

‘I also think it is Victorian.’

‘It cannot be both Georgian and Victorian those styles are completely opposite.

Make up your mind.’

That short conversation illustrates the difference between exploration and judgement.

The exploring person is putting forward possibilities.

The judging person is using judgement in two distinct ways.

The first way is to judge the suggestion immediately and to reject it probably on good grounds.

The second way is to insist that two more or less mutually exclusive styles cannot coexist: there has to be a choice between them.

There are two (at least) types of conversation.

In the first type the other person challenges you at every point and will not let you get away with anything.

Every point has to be argued and proved.

In the second type the other person listens and does not interrupt.

When you have come to a conclusion, the other person might then come back to a point you have made a point on which the conclusion rests and ask you to prove that point.

We are taught to use judgement as a ‘gatekeeper’.

This gatekeeper checks the credentials of everything that we allow into our minds.

Everything has to be checked as true or false.

It is like a modern office building with tight security at the entrance.

The security has to be tight because once you have entered you are free to move around and no one bothers you any more.

There is only the ‘entry’ check, so it has to be very good.

That is how we have been taught to use judgement.

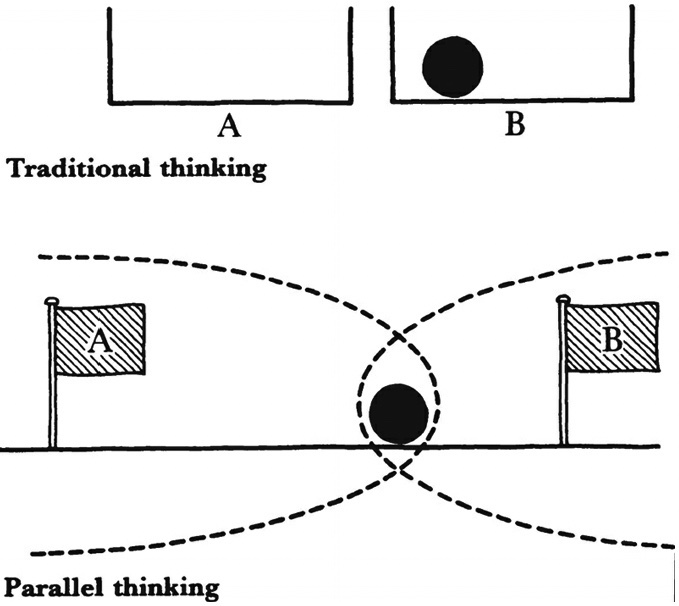

Consider the difference between a chain and a rope.

With a chain each and every link has to be sound, otherwise the chain is useless and will break.

With a rope, however, each strand does not have to be sound.

Some can be weak and the other strands will take the strain.

The rope is a ‘parallel’ system.

The chain is a sequential system.

In exploration you allow in possibilities.

They remain as possibilities.

Even mutually exclusive possibilities are allowed to enter and are laid alongside each other.

In the analogy of the building security, there would be no entrance check but every entrant would be regarded as a possible risk all the time he or she was in the building.

There would be no one-step security clearance.

There would be no gatekeeper function, and no permanent acceptance either.

All ‘possibilities’ would be regarded with suspicion.

This security analogy makes another important point.

With the gatekeeper use of judgement, once there has been clearance and something has been accepted as ‘true’ then that something is never re-examined.

That is how Socrates could make his points.

He got his listeners to accept one point after another.

If the listeners had once said ‘maybe’ then the whole chain would have collapsed.

The gatekeeper use of judgement leads to two possible errors:

1. We permanently reject something that is actually correct but perhaps within a different paradigm.

2. We permanently accept something which seems right at this moment in time but not in other circumstances.

It was to avoid this error that the sophists, and their equivalent today, preferred the relative notion of truth except in ‘game truth’ (where we set up things).

With parallel thinking we enrich the field with ‘possibilities’ and then proceed to design the most appropriate action or decision.

A stinking fish can stink out the whole refrigerator.

Similarly the acceptance of a false assumption can eventually wreck all the thinking based on it.

In the gatekeeper system, once we have put the fish in the refrigerator then we forget all about it.

In the parallel system, we keep everything out in the open and acknowledge that the fish may stink.

In the parallel system, we are not going to keep the fish around for any length of time.

The gatekeeper use of judgement can be an offensive weapon.

The arguer sets up dichotomies usually false and then forces the listener to choose between them.

‘This man is either honest or dishonest.’

‘Either we go into Europe or we do not.’

‘We give in to the union demands or we stand our ground.’

The listener is immediately given an either/or choice and tends to choose the most acceptable.

The speaker then has the listener where he or she wants the listener.

The next step proceeds.

Socrates used this very method almost all the time.

His listeners were constantly offered choices in which the ‘reasonable’ choice was much stronger than the ‘unreasonable’ one.

In this way Socrates edged his listeners along.

It is usually difficult for a listener to say ‘I want both of those.’

‘I don’t accept those choices.’

‘I see no need to make that choice at this point.’

In the traditional thinking system we see the very early use of judgement.

This is characteristic of the system.

This early use of judgement may serve either of two functions:

1. The gatekeeper function, to accept or reject what is offered.

2. The identifying function, to find the right ‘box’.

In any classification system there is a great deal of attention at the edges.

Does this go into box A or box B?

ls this a fruit or a vegetable?

Do I treat this as a personal expense or as a business expense?

A great deal of education and a great deal of philosophy is focused on just such discriminations.

This is absolutely essential in the judgement/box system.

You have to be sure where you are putting things, because they will stay there.

In the parallel system you would be less concerned at the beginning.

You would say: ‘Let us treat it as both A and B. ‘

You might make a copy and put one copy in file

A and another in file B.

When all the factors have been collected and it is time to make a decision or to take action, only then does a decision have to be made.

It may be that part of the expense is a legitimate business expense and part is a personal expense.

We are used to classification ‘boxes’.

Something has to be in one box or another.

This point is a ‘plus’ point or a ‘minus’ point.

How can it be both?

But it can depending on the circumstance and the perspective.

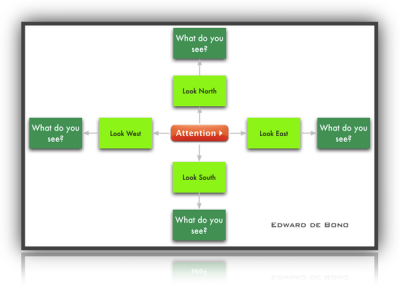

Instead of classification boxes which are based on the judgement system, we can have exploratory windows.

You look out of window A and you see what you see.

You look out of window B and you see what you see.

There may be a lot of overlap.

Someone may see through window A what you see through window B.

It does not matter.

What is seen does not belong to A or to B: you are interested in the total view.

The windows are merely aids to getting a fuller view.

So when students use the PMI attention-directing tool there is not the intention to classify observed points as ‘plus’, ‘minus’ or ‘interesting’: the intention is deliberately to look through these ‘windows’ and to see what you see.

There may be overlap.

The same point may be found under different headings.

It is all a matter of emphasis and of sequence.

I am not ‘against’ judgement.

Judgement is an important mental operation and is essential at some points.

It is a matter of sequence.

Do we judge first or do we explore first and then judge after we have explored and after we have designed the action or decision?

The Socratic system was very concerned with judging right away possibly because it was intended to deal with subjects, like ethics, where this was somewhat more appropriate.

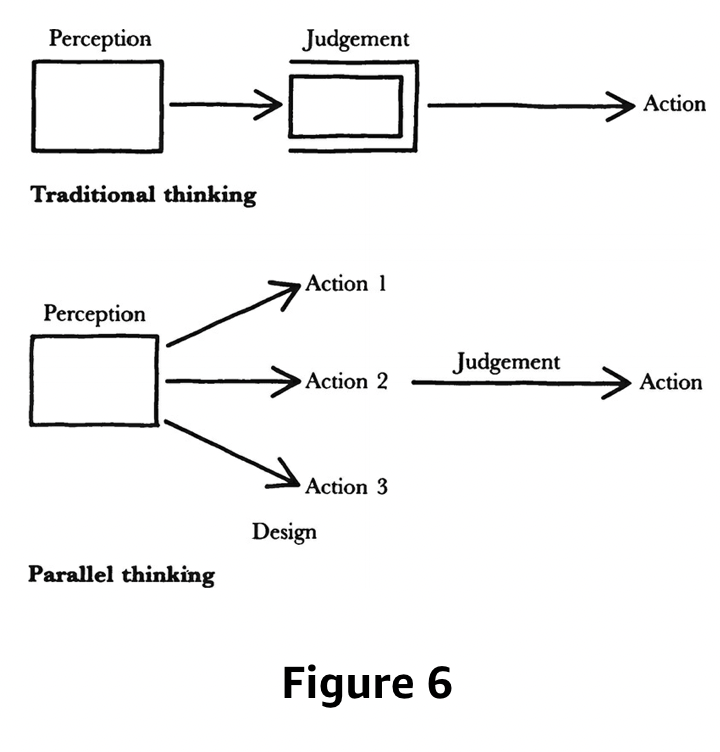

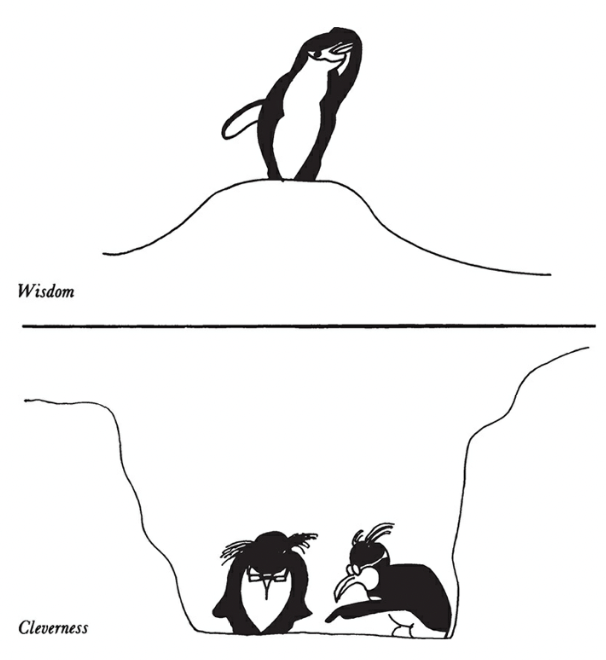

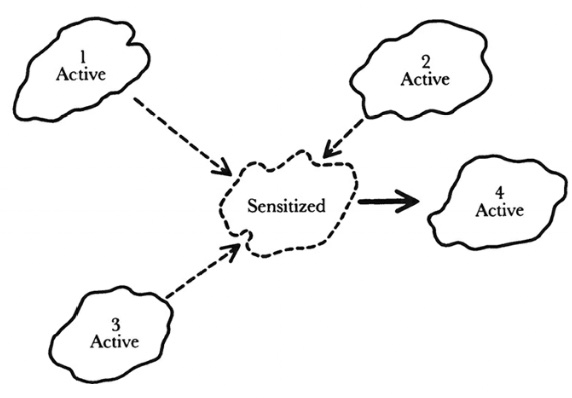

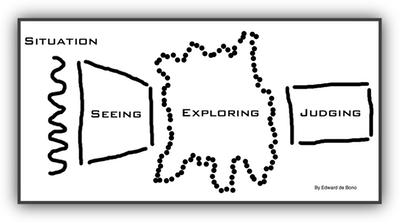

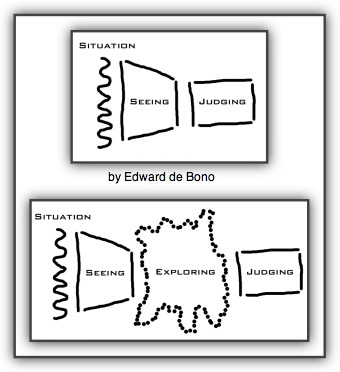

The difference is suggested in Figure 6.

As regards emphasis, we put far too much emphasis on judgement and far too little on exploration.

To suggest that we have to reject judgement in order to embrace exploration is to fall exactly into the trap set by the traditional thinking system, which insists that you must attack something in order to suggest something else.

Judgement is fine in its right place.

Judgement is very useful, but it is totally insufficient without exploration and generation of ideas.

Then there is the matter of the ‘outcome’ of the judgement.

Should this be the absolute certainty that we normally seek?

Should things be put into their ‘truth’ boxes?

Or should the outcome of judgement also be a ‘possibility’, but a rather stronger possibility than the exploration ‘possibility’?

‘I judge this to be true.’

‘I judge this to be a strong possibility.’

Judgement does not have to imply the true/false dichotomy with which Plato and the Gang of Three endowed it in order to escape the relativism of the sophists.

As in the analogy of the chain, judgement insists that we have to be ‘right’ at each stage.

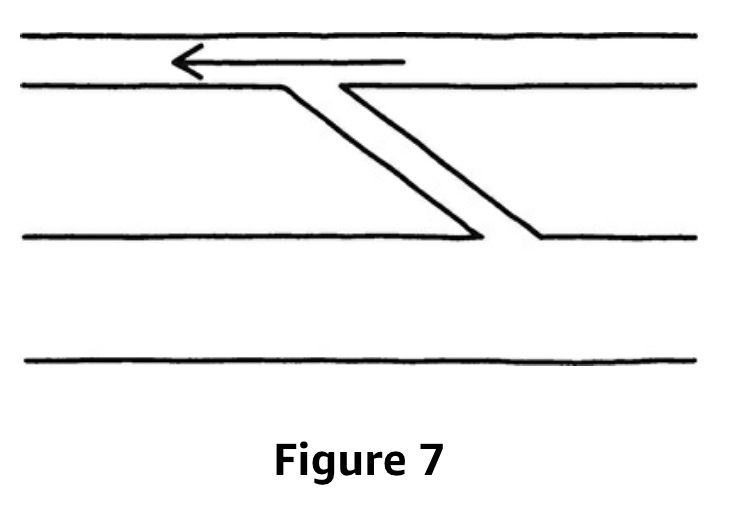

In Figure 7 a motorist is proceeding along a narrow road.

There is a turning to the left, but obviously it leads backwards and away from the direction in which the motorist is proceeding, so the motorist rejects it.

Yet, with a helicopter view, we can see that the side road leads to a much better road that leads in the desired direction.

Should the motorist have explored the side road?

Probably not, because we have to use practical frames of judgement.

The purpose of the illustration is to show that judgement is a matter of ‘practicality’, not truth.

In ‘truth’ the side road was valuable.

As a practical strategy the side road could not be taken.

When driving along a motorway it is sometimes necessary to take a turning heading south when you really want to go north.

In this known context we accept the need to go in an apparently opposite direction.

The provocative techniques used in the deliberate creativity of lateral thinking seek to set up instabilities in order to get us out of the comfortable ruts of our usual patterns which have been formed by a particular sequence of experience.

There is the new word ‘po’ which invented many years ago to signal a provocative operation.

With provocation we are allowed to say things which we know to be incorrect in order to ‘move forward’ from the statement to a useful new idea.

The asymmetric nature of patterns in human perception makes something of the sort essential.

We might say:

‘Po cars have square wheels.’

‘Po the factory is downstream of itself.’

Having to be correct at every step makes creativity virtually impossible.

The first statement is totally contrary to our understanding of engineering principles.

The second statement is contrary to normal logic: how can something be in two places at the same time?

Judgement would have to throw out both statements as being total nonsense.

Yet from the first statement through the process of ‘movement’ (a formal mental operation) we move on to the concept of ‘intelligent suspension’ in cars.

Using ‘movement’ on the second provocation we move on to the idea that if a factory is built on the side of a river then the ‘input’ must be placed downstream of the ‘output’ so the factory is the first to get its own pollution and needs to take steps to clean it up.

Having to be correct at every step makes creativity virtually impossible.

The instant judgement of an emerging idea will almost always lead to rejection of that idea.

In the Six Hats system of exploration such rejection would not be permitted, because the ‘black’ hat would only come later.

It is not my intention here to go into the details of the techniques of lateral thinking, which have now been in use for many years with considerable success.

Those who are interested in that aspect should read the books indicated in the footnote fn 1

Having looked at the gatekeeper aspect of judgement, which is concerned with true/false and accept/reject, we come now to the identification role of judgement: into which ‘box’ does this go?

I have a fax machine with a little window which indicates what is going on.

When things are not going on, the window indicates ‘Error 003’.

I look this up and it says: ‘No recording paper.

Action: insert new recording paper.’

Or it might be ‘Error 127’.

I look this up and it says: ‘Facsimile terminal not compatible.

Action: contact the other operator.’

This is very sensible indeed.

How else is the operator going to know what is going on and how to take the right action?

The fax machine has itself identified the error.

Once the error has been identified then the action follows automatically from that identification.

The immediate use of judgement for box identification is exactly similar.

We make the diagnosis.

We make the judgement.

Once we have judged that something fits into a particular box or category then the subsequent action is preset, easy and automatic.

There are general boxes like ‘attractive’, ‘unpleasant’, ‘friend’ and ‘enemy’, with some general actions attached to them ‘seek out’, ‘take further’, ‘avoid’, ‘be careful’, etc.

In some cases animals react immediately, out of instinct, as soon as their senses have been given enough information to identify a situation.

The box/judgement system seeks to do the same for humans instant judgement to give identification and then instant action.

Life is this way simplified.

In a preceding section have dealt with the rigidities and dangers of the box system and its certainty.

It may be useful, however, to point out again that the action which follows from the box identification (‘He is an enemy’) is automatic and crude.

There is very little ‘design’ of action.

In fact the traditional thinking system believes that ‘knowledge’ is enough and that action is easy: you just move towards the good things and away from the bad ones.

That is why we have paid so little attention to ‘operacy’.

In contrast to the automaticity of the judgement/box method, with parallel thinking we enrich the field with ‘possibilities’ and then proceed to design the most appropriate action or decision.

When we have the proposed course of action, or decision, then we relate this to our needs, to the available information, to the situation.

This final stage is a sort of judgement or comparison process.

‘He has no experience running a hospital.

We should reject him.’

That would be the normal judgement approach.

‘His experience is in banking and in running a large hotel.’

‘He is good at getting things done.’

‘He gets on well with people.’

‘In a way a hospital is a sort of hotel.’

‘He can make decisions.’

‘The other applicants are very traditional.’

‘Having considered all the factors think we should try him out.’

The parallel exploration puts down many more factors.

This is in contrast to the judgement approach, which seeks, as soon as possible, for a basis for acceptance / rejection.

There is a fundamental difference between parallel thinking and the judgement-dominated traditional thinking system.

The latter arose directly from the concern for ‘truth’ which was so important to Plato and subsequently to the Church and to feudal societies.

It should also be remembered that the original purpose of education was that a small band of people in society (lawyers, scribes, thinkers) should ‘know’ things.

Such people would be called upon for their input when the people of action (kings, builders, merchants) needed a knowledge input.

This is very similar to a person today using a computer database to obtain information as required.

So it is not at all surprising that education has never been concerned with action, with design or with creativity.

Our admiration for a ‘classical education’ fossilizes that attitude.

Knowing has always been more important for education than exploring.

So judgement has been taught as the dominant feature in thinking.

23 Information vs. Ideas

Thinking is no substitute for information.

Information is essential.

Information has a high value.

Information is a ‘good thing’.

Since information is good, more information is even better.

There are people who believe that if you get enough information then the information will do your thinking for you.

Many people in business believe that.

Of course, if information really could make the decisions then we should not need people, because information in a computer would flow along to give the decision output.

This may happen in the future.

For the moment, the human being is a sort of junction who adds to the information, ideas, values and politics and then passes on to a decision.

In the past, information was the real bottleneck, so any improvement in information would lead to an improvement in thinking and in the quality of decisions.

Information access and handling (by computers) have widened that bottleneck.

So we move on to the next bottleneck.

This is ‘thinking’.

What do we do with the information?

Most people in business and government have not fully faced that change.

If information is good, more information is better.

This follows directly from the traditional thinking system.

In a different book (fn1) I have dealt with the problem of the ‘salt curve’.

Food with no salt tastes bad; some salt tastes good; too much salt tastes bad.

I indicated that traditional thinking has a very hard time with such situations.

In a previous section I mentioned how Socrates had trouble with the definition of bravery.

No knowledge meant that you were not brave, some knowledge meant you were brave, more knowledge might mean that you were not brave and so on.

There are times when too much information clutters up the system, obscures what is really important, and reduces flexibility.

If you have to go into the most minute details of every person you interview then the process is going to take so long that you are only able to interview a few people.

We love information because it is unquestionably valuable and it is easy to deal with — especially today.

Education loves information.

There was a time when it was possible for education to give a student virtually all the known scientific knowledge.

The attitude of accumulating all possible information has persisted even though it is, today, total nonsense to try to do so.

There is, however, a dilemma.

Everyone knows that a little bit more of information is very valuable.

So where do we draw the line and say that it is not practical to teach more information?

Where do we draw the line in order to say that we should spend time on teaching thinking skills rather than on teaching more information?

It is not at all easy — which is why it is not happening.

It is the concept through which we perceive the information that gives it any value.

Information is easy to handle.

There are books and libraries.

You can put a book before a student and keep the student busy that way.

The sheer mechanics of information are practical and attractive.

Ideas are a different matter.

How do we produce ideas on demand?

We can read about other people’s ideas, but that is information.

We may believe that ideas are a sort of divine inspiration over which we have no control.

That is an old-fashioned view.

We can design and produce ideas as easily as we can produce information or even more easily.

The deliberate and formal techniques of lateral thinking can do this and are currently being taught in some schools and colleges.

There is no mystery about the processes.

Many people still believe that analysis of information will, itself, create new ideas.

This is not so, since the brain can only see what it is prepared to see.

The analysis of information will allow us to select an idea from our repertoire of standard ideas but not to find a new idea.

To ‘see’ a new idea we have first to imagine or speculate, so that the idea has a brief existence in our mind.

Then we may be able to see the idea in the information.

This is why hypothesis and ‘possibility’ have played so dominant a role in scientific development.

Even today, people teach science as if it is all about collecting data and doing experiments.

Yet the key driving force of science is the ability to create hypotheses.

In practice it is very rare in any science course for students to be given training in creativity and in the generation of hypotheses.

Designing experiments and analyzing data are an important part of science, but the hypothesis comes first.

Nor is it always enough to have simplistic hypotheses like the hypothesis that X affects Y in some way.

A correlation might be shown, but real progress comes about only when some model can be conceived.

A stack of correlations is not worth much.

Yet most of science today is done on that basis.

The real work lies in imagining and testing mechanisms and models.

The analysis of information will allow us to select an idea from our repertoire of standard ideas but not to find a new idea.

Analysis of the sales of life insurance might suggest that single people are not heavy buyers.

Why should they be?

They have no families that might be affected by their sudden death.

So the insurance company sees no market in single people.

The analysis of information has shown ‘what is’ in the usual way.

But if the concept of life insurance is changed to include the ‘living-needs benefits’ concept devised by Ron Barbaro in Canada (using lateral thinking) then, suddenly, life insurance is very attractive to single people because it also becomes catastrophic-illness insurance.

The new concept is that if the insured person gets a serious illness which might be fatal then the insurance company will immediately pay out 75 per cent of the benefits which would otherwise be payable only on death.

This money can be used for medical care.

The mathematical analysis of queues has been well worked out in operations research.

It is possible to work out the waiting time, the number of serving positions needed, etc.

But analysis of this sort is not going to lead to the new idea of having an extra serving position indicating that if you want to be served at that position then you pay a small fee.

If too many people use that position the fee is raised.

The money collected goes to open a further serving position, so benefiting everyone else as well.

In this way someone in a hurry can set a value on his or her waiting time.

Ideas are organizing structures which put values and information together in new ways.

Ideas need creative effort.

Just collecting more information or analyzing it more thoroughly will not produce ideas.

This seems so obvious, and yet the bulk of our activity is spent on those activities and not on the generation of ideas.

It could be that we do not see the value of ideas.

This is hard to believe.

It could be that we hope that analysis and more information will produce the needed ideas.

Both experience and a simple understanding of the nature of self-organizing information systems will tell us that this is unlikely to be sufficient.

We may believe that only chance and genius can produce ideas and there is nothing we can do about it.

I suspect that this last belief is responsible for our lack of attention to serious creativity.

In all fairness, it has to be said that many of the approaches to creativity are so ‘inspirational’ and insubstantial that the field has something of a bad name.

The belief that it is enough just to be liberated and to mess around with brainstorming does not build confidence in serious creativity.

Yet those who want to investigate the field more thoroughly have an ample opportunity to do so.fn 2

As in so many points in this book, it is not an either/or matter of either information or ideas.

Both are needed.

But, as with so many of the points have sought to make about our traditional thinking system, we have been obsessed with just one aspect that is valuable but insufficient.

This was the case with criticism, with judgement, with analysis and now with information.

Socrates was not obsessed with the search for information, although he did work by collecting as many examples as he could of what he sought to define.

Our obsession with information arises more directly from the ‘search-for-the-truth’ idiom.

We believe that information is ‘truth’ and therefore the more information we have the nearer we come to that ‘full truth’ which will tell us what to do.

We forget the very close relationship between ideas and information.

It is the hypothesis idea which directs our search for information.

It is the perceptual truth which helps us to interpret the information and give it credibility.

It is the concept through which we perceive the information that gives it any value.

There is a further point which needs mentioning.

Universities only really got going at about the time of the Renaissance, although many had existed before.

It was the Renaissance that opened up universities to new and secular thinking.

Before that they had been largely concerned with theology and scripture.

At the Renaissance it was obvious to everyone that the best ideas were going to be obtained by looking backwards at what had been done by the Greek thinkers and the Roman doers.

So it was a unique period in history when looking backwards was indeed more progressive than looking forwards.

This practice has continued to this day and is dignified by the name of ‘scholarship’.

Work is valued mainly in terms of how competently it looks backwards and rarely on how well it might affect the future.

We esteem the value of collection more than we esteem the value of concepts.

The nonsense of this will be shown in the future when computer programs will be able to look through the literature, pick out all relevant papers, and then extract from them (through theme search) all relevant paragraphs and put these together as a scholarly work.

The library function which is the basis of so much university work will then be taken over by computers.

People should then be freed to think.

24 Movement vs. Judgement

Judgement is a well-recognized thinking operation.

‘Movement’ is a different mental operation that is used from time to time but is rarely recognized as a deliberate and useful thinking operation.

Judgement is concerned with ‘what is’.

Judgement compares a situation or a suggestion to past experience and gives a verdict of ‘match’ or ‘mismatch’: this fits or this does not fit.

Judgement is static.

Movement is concerned with ‘what can be’ or ‘what may be’.

Movement opens up possibilities.

Movement looks at where the situation or suggestion leads.

What follows next?

The judgement system is what I call ‘rock logic’, fn1 because rock is static and has permanence.

The movement system is what I call ‘water logic’, because water is concerned with flow.

The key word in the judgement system becomes ‘is’.

The words ‘yes’ and ‘no’, ‘true’ and ‘false’, are really convenience versions of ‘is’.

The key word in the movement system becomes ‘to’.

‘Where does this lead to?’

Judgement is concerned with establishing the solidity of each step in terms of past experience.

Movement races ahead to open up possibilities that can come together as a new idea.

Judgement is about description.

Movement is about creation.

We can say that sugar is white (or brown), but can we say that sugar is sweet?

What we are really saying is that if we put the substance in our mouth it would give us the sensation of sweetness.

So, in a sense, sugar ‘leads to’ the sensation of sweetness.

Only sight and smell give instant appreciation; other qualities involve a ‘test situation’.

If you say that a suitcase is heavy, this is because you have lifted it already or you think that if you tried to lift it the case would be heavy.

You can say that shoes are black, or seem big, or are smelly.

But if you say that shoes are comfortable or expensive then you are putting the shoes into a special situation; wearing them or buying them.

These special situations or test situations occur in our mind.

It is in the inner world of perception that we run our thought experiments, which may look forward into the future or backwards into the past.

It is in the inner world of perception that the operation of ‘movement’ becomes important.

Quite often in the outer world of reality one thing may lead to another.

An insult may lead to a fight.

A puncture will lead to stopping the car.

A prize may lead to joy.

But in the inner world of the patterns of perception one thing almost always leads to another.

It is in the inner world of perception that we run our thought experiments, which may look forward into the future or backwards into the past.

Imagine a knife lying on a table.

HaIf an hour later that same knife is still lying on the table.

Nothing has happened.

But in the world of perception as soon as you see the knife several possible ‘movements’ occur.

You may wonder how it got there.

If it is a domestic type of knife you may think of food.

If it is an ugly knife you may think of violence.

The inner world of your mind moves on from the knife to something.

This movement may be passive, as in association, significance and meaning.

What we see triggers a train of associations.

What I am concerned with here is the ‘active’ use of movement as a deliberate mental operation.

Judgement can be instant and automatic or it can be deliberate.

The same applies to movement.

We use movement as a deliberate operation to open up possibilities for the exploration and creativity of parallel thinking?

‘What follows?

‘What does this lead to?’

“What does this open up?’

‘What are the possibilities?’

‘Where do we go from here?’ ‘Movement’ is a very valuable operation in creative thinking.

With the provocative techniques of lateral thinking, movement is essential.

In provocation we use the signal word ‘po’ to indicate a provocation, which is a statement we make purely for its ‘forward effect’ (to see what happens next).

In seeking to generate some new concepts for restaurants, we might put forward the provocation, ‘Po a restaurant without food.’

Judgement would immediately reject that idea on at least two grounds: 1.

There would be no reason for anyone to go.

2. Without food it would not be a restaurant at all.

Judgement might also add that even if people did go how would you get any payment from them?

It would be the correct role of judgement to relate this suggestion to our current experience.

It is not enough to judge.

You cannot grow a garden just by wielding the shears.

You do have to plant things from time to time.

Many traditional approaches to creativity, like brainstorming, would therefore insist on ‘suspension’ of judgement in order to avoid this instant rejection.

But that is very weak.

Suspending judgement is not itself an operation.

What we need is the active mental operation of ‘movement’.

If the restaurant does not provide food then that ‘leads us on’ to the idea that the customers bring their own food.

This leads us on to the idea that the restaurant is a conveniently placed, well-decorated, indoor picnic place.

Just as people might picnic on a riverbank in summer, so in winter they come to ‘picnic’ in the restaurant.

The restaurant charges them for admission and service.

The restaurant might provide the plates, etc., and possibly the drinks.

We can ‘move’ further.

Where are the people going to get the food from?

Perhaps they could buy the food from a whole range of takeaway vendors outside.

This would now resemble the hawker restaurants in Singapore.

Or they might buy frozen food from a nearby supermarket and each table in the restaurant would be equipped with a microwave oven.

There are various frames of ‘movement’ which go beyond simply association.

One frame is to seek to extract a ‘principle’ or ‘concept’ and then to work forward with this.

‘Po the restaurant has rude waiters.’

The extracted principle is that the waiters have a definite personality and are not polite and invisible.

From this we move forward to the waiters/waitresses being actors who perform a defined role.

This role is described on the menu, and you can order your waiter/waitress just as you order a dish.

You might choose a quarrelsome waiter in order to impress your guests with your macho style.

You might choose a comedienne waitress for amusement.

You might choose an eccentric waiter for the pleasure of surprise.

Another frame for ‘movement’ is to imagine the provocation being put into effect and watching what happens ‘moment to moment’ in order to move on to a new idea.

‘Po the restaurant has no plates.’

We could simply move on to the idea of eating off scrubbed wooden surfaces or banana leaves.

This is not particularly interesting.

We could imagine someone going to a restaurant that was known to have no plates.

So the customer brings the plates.

Now you would not want to be carrying plates around all the time, so you leave your plates in the restaurant and dine off them when you go to that restaurant.

From that we ‘move’ on to a restaurant for business entertaining.

A company has its plates embossed with its logo and special design.

These plates are stored in the restaurant.

Business entertaining takes place on your own plates.

From the restaurant’s point of view this also means that you would tend to do all your entertaining in that restaurant.

There are other frames for ‘movement’ such as: focus on the difference, special circumstances, positive aspects, etc.

These are covered in specific books on the techniques of lateral thinking.fn 2

In ‘movement’ we are really saying to ourselves: ‘In this frame, where do we move to from this starting-point?’

There does not have to be a specified frame, and some people become very good at movement without needing to specify a frame.

But movement is much more than just casual association.

While skill in movement is essential in lateral thinking and very valuable in any sort of creativity, it is also of a more general value.

The purpose of movement is to suggest things and to open up possibilities.

This is all part of the exploratory process of parallel thinking.

The possibilities generated exist in their own right in parallel.

Not all are valuable.

Not all are feasible.

Not all are probable.

Those that are not valuable, not feasible and not interesting will contribute little to the design of the final outcome.

A buffet table can hold a wide variety of food.

You put together your meal from a selection of the items.

In the same way the final design of the outcome in parallel thinking is under no obligation to use or attend to all the possibilities that have been generated.

You see the landscape and you choose your route.

Traditional thinking places the emphasis on judgement and the need to be right at every step.

With creativity, you do not need to be right at every step so long as the final idea has value.

We do not need to derive the value of the final idea from the validity of each step on the way there.

We can assess the final idea in its own right.

What does it offer?

What are the risks?

What are the costs?

On the way to the final idea we may use provocations which we know to be ‘wrong’, but these act as stepping stones not judgement points.

With the mental operation of movement we go forward from such points.

Movement has a generating function.

It is not enough to judge.

You cannot grow a garden just by wielding the shears.

You do have to plant things from time to time.

It is a fundamental weakness of the traditional thinking system that it is so poor at generating.

The attempted synthesis of thesis and antithesis is a very weak generating technique, both because its application is limited and because the process is not creative.

26 Inner World vs. Outer World

The inner world is the world that exists in our minds: the world of perception.

The outer world is the world out there: the reality with which we usually need to cope.

The inner world is the train that you think leaves at 17.30.

The outer world is the train you have missed because it actually left at 17.00.

Plato and Socrates were not directly concerned about people catching trains but indirectly they were much concerned.

Obviously, if people have their own ideas about when trains run then everyone is going to be in a bit of a mess and society is not going to run smoothly.

Would it not be better to have objective, printed timetables which people could consult and so get to the station on time?

Does this merit being accused of fascism?

Mussolini's greatest contribution to Italian culture was that he made the trains run on time.

Protagoras, the great sophist, was some 15 years older than Socrates and he and his fellow sophists taught/preached an extreme form of subjectivism.

What seems to be the truth for me is the only truth for me there can be no other.

No man can tell another man that his perceptual truth is mistaken.

Things are as you perceive them.

Protagoras pointed out that all perceptions and judgements were equally true but not all were equally valid.

If everyone perceives that a stream is not contaminated then that is the 'truth' for them, but this judgement is not valid because many of those drinking from the stream get cholera.

In an earlier book of mine I wrote about 'logic bubbles'.fn1

A logic bubble is that temporary collection of perceptions, needs and emotions within which everyone acts perfectly logically.

It is no use attacking the logic of people's actions, because to them they are indeed logical.

The best you can do is to broaden or clarify their perceptions.

That is why teaching perceptual thinking (as in the CoRT Thinking Lessons fn2) can be so important.

Plato and Socrates claimed, believed and insisted that there was an objective truth out there somewhere.

This was a truth which would be equally true for everyone.

It would be strong enough to resist the efforts of the sophists to persuade people of other versions of the truth.

There was the fundamental notion that the inner, subjective, world is inaccurate, misleading and capable of being deceived.

We should seek to get rid of this dangerous inner world by bringing in the truths from the outer world so our inner view coincides as accurately as possible with the external world.

Science should replace myth.

Measurement should replace guessing.

This is the idiom that has persisted to this day: a great suspicion of the unreliability of the inner world.

Because of this suspicion, we have paid virtually no attention to the very important matter of perception but have left that to the arts.

We have concentrated instead on 'processing' which can be checked out in the outer world.

You can measure triangles: you do not just have to imagine them.

Why use any map except the most accurate?

Should not the inner world reflect as accurately as possible the outer world?

Surely this is what discovery and education are all about?

At one extreme there is an inner-world map which is so accurate a representation of the outer world that predictions can be made and useful action can be taken.

At the other extreme the inner-world map is so very bizarre that the person is a danger to himself or herself and to those around.

There are times when schizophrenics have an inner world which interprets the outer world in a totally unusual way.

If we look at these two extremes then we are likely to favor the accurate inner-world map, because it permits us to operate effectively in the outer world where we earn a living and associate with people.

But the inner world has its own huge importance: love, dreams, beauty, fantasy, values, beliefs, etc.

In the end it is the inner world which makes life worth living.

The real purpose of the outer world is to keep us alive and to feed the dreams of the inner world.

Important as these values of the inner world might be, I am not concerned with them in this book.

I am concerned with the 'thinking' value of the inner world.

What does the inner world contribute to our thinking?

Is the search for outer-world truth enough?

Possibilities exist in the inner world.

Three people see a dog.

One person, who is scared of dogs, thinks there is a possibility that the dog might attack.

The second person thinks that the dog will attack only if the dog's territory is invaded.

The third person, who likes dogs, thinks there is a possibility that the dog could be friendly if given the chance.

Just as memories go backwards in our minds, so possibilities go forward in our minds.

There may be evidence for a possibility but not yet any firm proof.

Should we be allowed to hold that possibility because it exists in our inner mind?

With parallel thinking there is no question: the possibility is valuable.

With traditional thinking we should immediately proceed to judge it as soon as it appears.

In the end it is the inner world which makes life worth living.

The real purpose of the outer world is to keep us alive and to feed the dreams of the inner world.

A hypothesis is an organizing possibility.

In a previous section — I commented upon the huge value of the hypothesis in Western technical progress.

The hypothesis allows us to direct attention and to set up experiments.

The hypothesis provides an organizing framework for what we see.

The hypothesis gives us something to work towards and to work upon.

The hypothesis is what we bring to the situation.

The hypothesis exists only in the inner world.

Visions and objectives exist only in the inner world.

An objective is something we want to work towards.

We have to imagine the destination in order to plan our route.

With a vision, we imagine the completed picture and this motivates us, and others, to set about making the picture reality.

Without vision we should just react moment to moment, following the sensations and needs of the moment.

Concepts exist only in the mind.

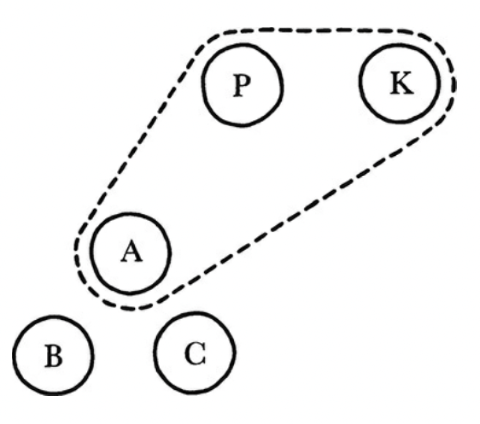

In Figure 8, if you choose to group A, P and K that is because you have some internal reason for doing so.

The external grouping would have been A, B and C, because they are close to each other.

Figure 8

Concepts such as morality, justice and beauty exist only in our minds.

Plato knew this full well, and yet he wanted to give them the unchanging objectivity of matters that exist in the objective world.

So he created the notion of 'ideal forms' which have always existed in the mind but are true, universal and unchanging.

So Plato acknowledged the huge importance of the inner world of perception but wanted to escape from its subjectivity and variability.

Belief is the most powerful of the inner-world behaviors.

Belief goes beyond a tentative possibility to an inner-world 'truth'.

In ordinary language, belief is sometimes used as being 'less than sure'.I prefer to call this a 'possibility'.

I shall use the word 'belief' for something which is held 'to be so'.

Belief is inner-world truth.

You can believe that falling from a fourth-floor window will cause your death even if you have never tried it.

You can believe that a stream contains cholera germs because people who drink from it get cholera.

At its most powerful a belief is a perception that forces us to look at the world in such a way that the perception is validated.

If you believe someone to be nasty then your perception will select those aspects of behavior which validate the belief.

If you consider someone to be selfish then you will note those aspects of behavior which convert your consideration into a belief.

Plato's world view was itself a belief system.

He believed that there were ultimate truths everywhere, just as there seemed to be in mathematics.

If there was any difficulty in finding those truths then that was due to Socrates's proclaimed ignorance.

This ignorance confirmed that the truths were there but could not be found.

Components always fit in around a belief system.

A belief system is usually a good example of the self-organizing nature of information in the brain.

Belief systems are circular and therefore difficult to interrupt.

They are not sustained by evidence in the outer world once they have been formed.

Whatever the actual information in the outer world, perception will choose to structure it so as to support the belief.

The key operation in perception is 'flow'.

This simply means that one event is succeeded by another.

This aspect of flow is described in my book Water Logic.

In that book work with this concept of flow to produce 'flowscapes' which are an attempt to make visible to a person what might be going on in that person's perception.

From the flowscape you can pick out what — call the 'collection points', the 'sensitive points' and the 'circular truths'.

All perceptual truth is probably 'circular'.

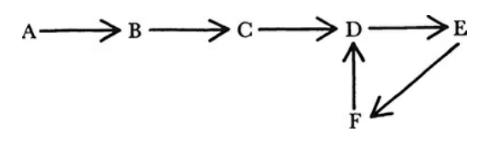

In Figure 9 we can see how A leads to B which leads to C which leads to D which leads to E which leads to F which leads to D. The final circle is now established.

It is difficult to see how perceptual truth could be anything other than circular.

To explain a situation we go from situation to hypothesis and then run the hypothesis in our minds to find results which fit the existing situation.

In science, proof is often no more than lack of imagination.

If one explanation closes the circle we assume it must be the only one which could do that.

Figure 9

I have often complained that we need a simple, succinct word that would cover 'the way we look at the world at this moment'.

That phrase is quite a mouthful.

The word 'perception' is too broad, because it covers the whole process of looking at the world.

The word 'perspective' indicates a position which might give rise to a particular point of view.

The phrase 'logic bubble' comes close but relates more to the logical action that arises from the particular perception.

By total chance a word suggested itself recently.

In an article I had written there was a typing error which produced 'mypopic' instead of 'myopic'.

This led to the possibility of using the word 'popic' to mean 'the way someone is looking at the situation at this moment'.

The 'opic' part of the word is related to the Greek for eye.

The 'p' or 'po' part can indicate 'possible' or 'potential'.

The simplest way to remember the word would be as 'possible picture' of the world or popic'.

'Your popic sees unemployment as an inevitable factor in society.'

'My popic sees inadequate mechanisms for income transfer.'

I believe his popic was that unemployment was a transitional state.'

'Your popic is very patchy and incomplete.'

'Lay out your popic alongside these others.'

At its most powerful a belief is a perception that forces us to look at the world in such a way that the perception is validated.

Why not just use the word 'view'?

Because 'view' suggests an outcome opinion, whereas a popic is a sort of picture without an opinion attached.

Will the word catch on?

I doubt it.

What conclusions can we draw from this consideration of inner and outer worlds?

1. The inner world has been much neglected in favor of the 'objective' outer world.

2. The inner world has its own truth and its own logic which are different from those in the outer world.

3. The logic of the inner world tends to be 'water logic' rather than the 'rock logic' of the outer world.

4. The inner world contributes greatly to our thinking ability in terms of hypotheses, possibilities and concepts.

5. The beliefs of the inner world are not easily altered by reference to the outer world.

There is a need to work in terms of inner-world logic.

6. The inner world is selective, subjective and fallible but should not be neglected on that account.

7. Thought experiments are as valid as experiments in the outer world.

8. Traditional thinking is largely ineffective when dealing with inner-world behavior.

We need to develop more ways of dealing directly with perceptions.

9. Values, metaphors, modeIs and objectives all exist in the inner world.

10. We may just need the new word 'popic' to describe 'a possible picture of the world around at this moment'.

30 Designing a Way Forward

If thinking is going to serve its various purposes then we need to move forward from the field of ‘parallel possibilities’ to the desired outcome.

This is where ‘design’ comes in.

In a previous section I contrasted design with analysis.

I indicated that analysis is concerned with ‘what is’, whereas design is concerned with ‘what can be’.

I indicated that the traditional search for the ‘truth’ is like prospecting for gold.

Worthy as this may sometimes be, it is not the same as designing and constructing a house.

You are not going to ‘discover’ a house you have to make it happen.

In general, use of the term ‘design’ is sometimes restricted to graphic design, theatre design, dress design, industrial design, etc.

Very often these aspects of design deal with the visual aspect, though the functional aspect is also important.

Design is often seen to be a cousin of ‘art’.

In this book I am using the word ‘design’ in the broad and strong sense in which believe it should be used.

For me, design is ‘bringing something into being to serve a purpose’.

While design may be creative, it does not have to be.

The emphasis is on making something happen.

It is not enough just to judge, criticize, refute and search.

You actually have to do something.

I have sought to show in this book that our traditional thinking system in its obsession with the ‘search for the truth’ has paid insufficient attention to developing the thinking skills needed for design.

Society cannot thrive on judgement alone.

In times of rapid change like the present, the need for design is more important than ever.

Judgement may just be enough to resist change but not enough to benefit from change.

In this section shall be dealing with design in a narrower sense: how we design an outcome from the field of parallel possibilities.

Traditional Western thinking, in its pure form, does not have or need a design stage.

Each step follows the last step with a judgement as to whether the step is true/false, right/wrong.

It is like a mason making sure that each stone is squarely and truly based on the preceding stone: ‘If this is so then this is so.’

In practice, of course, the purity of the traditional thinking method is contaminated by various attempts to generate alternatives, etc.

This is regarded as ‘somehow happening’, often aided by a simplistic analysis which assumes that you can either do something or not do it.

Society cannot thrive on judgement alone.

Judgement may just be enough to resist change but not enough to benefit from change.

With parallel thinking the design stage is very important, because without it the parallel-possibility stage has only a small value.

Several things may happen in the design stage of parallel thinking:

1. The outcome becomes obvious.

2. The outcome organizes itself.

3. The outcome needs to be designed deliberately.

If you go to a store to buy some clothes you may look through a variety of styles and try on different sizes.

If you have to make a decision you will need to consider price, utility, color, style, practicality, size, etc.

This is the hard way of making a choice.

Occasionally, however, you find exactly what you want: right style, right color, right size and right price.

The same often applies to buying a house.

Usually you have to try to convince yourself to buy the most practical choice.

Once again you consider all the factors.

Occasionally you fall in love with a house at first sight.

There are those who claim that marriage can also happen in either of those two ways: careful assessment or instant love.

The same thing can happen with the parallel possibilities.

The desired outcome can spring directly, and without further consideration, from the field of parallel possibilities.

It may depend on one of the possibilities or on a simple combination of possibilities.

Your travel agent tells you of the different ways you could get from Malta to Mexico City.

One of them stands out as being obviously the best.

A good map of a holiday country helped by advice from the locals will lay out the ‘landscape’ of the tour you want to make.

Designing the best route may be easy.

Thinking is not always difficult.

Thinking does not have to be difficult.

Traditional thinking often makes things much more difficult than they need to be, because traditional thinking is so poor at generating options and possibilities.

It is far easier to select from a wide range of possibilities than to reason your way to a good choice.

In practice, it is surprising how often the structured parallel thinking of the Six Hats method leads directly to a decision or outcome without any conscious design effort.

The outcome seems obvious when the possibilities have been laid out.

The second way in which the field of parallel possibilities can proceed to a useful outcome is through the process of ‘self-organizing’.

This is an unusual concept for those who believe that nothing happens unless at every moment we are making it happen.

The more we know about the brain, the more we come to realize that in at least some of its behavior it is a self-organizing information system.

That means that information organizes itself into patterns, flows and outcomes.

Those interested in these particular aspects could read about them in my other books fn1

Rain falling on to a virgin landscape eventually organizes itself into streams, tributaries and a river.

The river gets to the sea.

In exactly the same way, input laid out as parallel possibilities can sometimes organize itself into an outcome.

Sometimes two ‘rivers’ form and there is a double outcome.

We then have to choose between the two.

In life, designers and artists sometimes work this way.

They saturate their minds with the different ingredients, needs and possibilities and then wait for everything to organize itself into an outcome.

To help this process, we just read through the field of parallel possibilities over and over again and wait for some outcome to start forming.

The process is not as rapid or as complete as with the instant outcome mentioned previously.

There may be a stage in which a general concept forms and this gradually refines down into a practical outcome.

In the future we shall certainly have computer software which will allow a field of parallel possibilities to organize itself into a useful outcome.

Along with others, I am working on just such software.

In a sense, today’s neural-network computers do that by allowing experience over time to organize itself as a way of processing information.

There are some simple and easy-to-use techniques which we can apply in order to help possibilities to organize themselves.

One such technique is the ‘flowscape’ technique.’ Fn2

This is directly based on ‘water logic’ and how one perception flows to another.

A simple flowscape can be constructed around some of the notions put forward in this book.

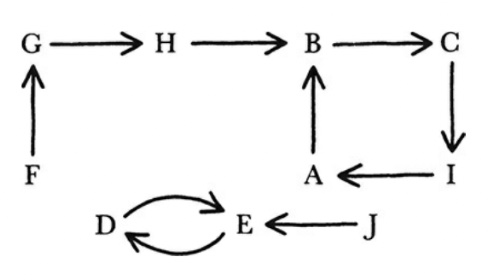

A Judgement is not enough. B

B There has to be something to be judged. C

C The generation of ideas is important. I

D We are complacent about our judgement system. E

E The system is good at defending itself within its own rules. D

F Generation of ideas involves possibility. G

G Possibilities need to interact. H

H Design can only be judged as a whole. B

I Both idea-generation and design are needed. A

J ‘What is’ does not ensure ‘what can be’. E

Figure 17

Each possibility is simply connected to one other possibility.

The resulting flowscape is shown in Figure 17.

At once it becomes obvious that, in the thinking of the person constructing the flowscape, the judgement system is content to defend itself and disregards the need for ideas.

We can also see that what is to be judged depends on both idea-generation and the design process.

The flowscape makes visible a structure in the thinking.

Sometimes this is obvious; often it produces a new insight.

Is this flowscape ‘true’?

It may give a reasonable picture of the thinking of the person making the flowscape, but even that is not certain.

But the important question to ask is not ‘Is it true?’ but ‘What happens next?’

The answer to this question may be highly useful and practical.

There is no point in trying to attack a system that is valid and content within its own framework.

The best approach is to show how the system is excellent but inadequate on the generative and constructive side of thinking.

One of the functions of the flowscape is to suggest the key points and the sensitive points.

These are the points that contribute most.

We can then focus attention on these points.

For example, we would need to check out these points.

Are they valid?

This is much simpler than checking out all points when some of them contribute very little.

Design is concerned with the following types of consideration:

‘What does this contribute?’

‘Can these be “combined”?’

“What are the values and concepts?’ ‘Is this valid?’

‘What does the outcome lead to?’

Design may have more than one stage.

In one-stage design we go straight from the field of parallel possibilities to an outcome.

In two-stage design we may go from the field of parallel possibilities to some alternatives and then proceed to choose from the alternatives.

In three-stage design we may first establish some concepts, then form some alternatives and finally make a choice between the alternatives.

There is no need at all to categorize these different sequences: it is enough to realize that sometimes you cannot go straight to the outcome.

The first step in design is usually one of comparison.

We look across the parallel possibilities to see how they compare one with the other.

We look for similarities.

Some of the possibilities may be saying the same thing in a different way.

Some are complementary or supplementary to each other.

Some may focus on a broad concept, and others on a particular example of the same concept.

This consideration of similarities may lead to the emergence of a more general concept which covers many of the possibilities.

There is no pressure to achieve this the exercise is not one of ‘grouping’ possibilities but such a concept may emerge naturally and can then take its place in the field as a possibility.

In contrast to the great readiness of traditional thinking to throw out one side of the contradiction, in the design process we seek to extract maximum value from both sides of any contradiction.

After considering similarities we can focus on differences.

These may vary from a difference of emphasis to possibilities that are contradictory, mutually exclusive and totally incompatible.

We explore the basis for the difference.

Perhaps it is looking at a different part of the same picture.

Perhaps the circumstances or context might be different.

‘He is a smoker.’

‘He is not a smoker.’

It turns out that he smokes at home but never in the office.

The two mutually exclusive statements turn out to be perfectly compatible.

After examining and seeking to understand the differences, there is an attempt to see if they can coexist.

It is not a matter of choosing between them or establishing which one is true and which one is false.nThe key question is: What do they contribute to the possible outcome?’

An attempt is made to reconcile out-and-out contradictions.

Are both positions valid but at different times, under different circumstances or for different people?

Can both be used?

Is it not possible to use both a carrot and a stick?

In contrast to the great readiness of traditional thinking to throw out one side of the contradiction, in the design process we seek to extract maximum value from both sides of any contradiction.

Sometimes we may need to create a third or further concept to embrace both the contradictory concepts.

For example, to embrace both ‘carrot’ and ‘stick’ we might have the concept ‘inducements to change present behavior’.

Carrot and stick now become alternative ways of carrying through that concept.

A worker may leave a company and not leave a company.

The worker can retire but immediately come back as a consultant.

The creation of new concepts is very much part of the design process.

Sometimes the new concept can be expressed neatly.

At other times it may be expressed as a phrase, such as ‘some way of separating the strongly motivated from those who just go along’.

We then seek ways of bringing it about.

We can express a need as ‘something’ or ‘some way’.

“We need some way of giving benefit to those who park outside the city centre.’

“We need something to prevent cars heating up in the sun.’

“We need some way of communicating with the local leaders.’

If we cannot reconcile contradictions and cannot show one side to be invalid, then we proceed to design an outcome which covers both possibilities.

‘We cannot decide whether he is competent for this job or not.

We can give him a trial period, we can monitor his progress closely, we can give him a competent assistant, etc.’

In practice, once you reject the either/or choices of traditional thinking, contradictions are not as great a difficulty as they may seem.

After comparison, we may proceed to extract values and concepts.

Sometimes we may want to do this before the comparison stage.

Sometimes we may have the comparison stage, then extract concepts and values and then compare again.

Some possibilities may already have been expressed in concept form.

From almost anything that has been offered as a parallel it is possible to extract one or more concepts.

You can even go from a concept to a broader concept.

From the concept of ‘road metering’, in which an electronic device records how much road a car has used during a given period, we can go to the broader concept of charging cars by their use.

In the design process, concepts are much easier to deal with than detail.

You cannot change detail but you can change concepts.

You can make a concept broader, you can modify a concept, you can combine concepts.

For example, there is no need to list every single flight from London to Paris.

It is enough to talk of ‘a regular and convenient air service between London and Paris’.

Skill in working with concepts is essential for the design process.

Concepts are groupings and organizations of experience which allow us to see things in a certain way and to seek for certain types of action.

If you are looking for ‘food’, you are more likely to find something to eat than if you are looking only for ‘a bar of chocolate’.

And if you are looking only for ‘a bar of Cadbury’s milk chocolate’ your chances will be even less.

Creativity can come in at any point in the design process.

There can also be defined creative needs: ‘We need a new idea to limit the mobility of teenagers in order to reduce crime.’

The creative need can be pinpointed and then the techniques of lateral thinking n3 can be used in a formal and deliberate way to generate new concepts and new ideas.

During the design process it is worth pinpointing areas of creative need: ‘We need some way of reducing street begging.’

That becomes a creative focus.

The outcome of the creative effort is added into the design process.

To be useful, a designed outcome must have a ‘value’.

From where does this value come?

It comes from the values involved in the situation and these include the different values of the different parties involved and from the values of the group or person doing the thinking.

In the case of an agreed problem then the value of the solution rests on its ability to solve the problem.

Has the problem been removed?

This sense of ‘value’ is constantly present during the design process, but it is not used as an accept/reject criterion for every suggestion.

It is part of the design process.

A fundamental aspect of the design process is to extract the values of the parties involved.

In the case of a conflict, there are the values of those involved directly, the values of those caught up in the conflict, the values of third parties, etc.

In negotiation, the values of those involved are central to the whole process.

The different parties have different values.

Successful negotiation means designing an outcome which satisfies the different values.

Occasionally it may be useful to design and insert a ‘new value’.

Values such as ‘gain’, ‘security’, ‘flexibility’, ‘status’, ‘recognition’, ‘dignity’ are all important.

How do these contribute to the design?

How are these taken care of in the design?

It is not only in negotiation or in conflict that values matter.

With any change whatsoever the values of those who are going to carry out the change and the values of those affected by the change are important.

Then there are the values of the organization: time, cost, disruption, image, etc.

Excellent abstract designs which do not take values into account remain unusable.

Values are not fixed absolutes.

Values can be added to.

Values can be changed.

There can be a trade-off in values where one value is given up in favor of another.

Values can be enhanced.

Values are not always obvious.

Sometimes even the person for whom a value applies is not aware of that value, because it is hidden or taken for granted.

‘Freedom from fear’ is seen as a value only when it is threatened.

In the end, concepts are only ways of delivering ‘value’.

So value is at the heart of the design process.

But, just as the enjoyment of a meal is the ultimate test of the value of the ‘meal outcome’, So the effectiveness of the thinking process depends on the values provided at the end.

The meal requires a lot of preparation, including assembling and preparing the ingredients and then cooking them.

In the same way the design process may be complicated in order to deliver simple values at the end.

There are several broad strategies of design.

1. Look to the desired or ideal outcome and work backwards.

2. Design around the dominant theme or value and fit the others in.

3. Try to combine the different needs and values and see what the result looks like.

Improve and modify as required.

4. Move ahead with a tentative design and allow the pressures of evolution to improve it.

5. Produce alternative designs and then compare them to each other and to the needs.

6. Select and borrow a standard design.

Modify as required.

7. Identify the key point, design to fit that and then build the rest of the design around this point.