Toward The Next Economics and other Essays

by Peter Drucker — his other books

#Note the number of books about Drucker ↓

My life as a knowledge worker

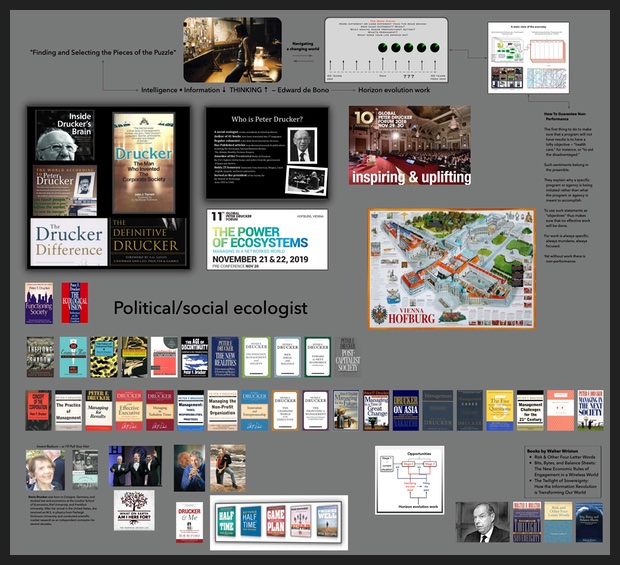

Drucker: a political or social ecologist ↑ ↓

“I am not a ‘theoretician’;

through my consulting practice

I am in daily touch with

the concrete opportunities and problems

of a fairly large number of institutions,

foremost among them businesses

but also hospitals, government agencies

and public-service institutions

such as museums and universities.

And I am working with such institutions

on several continents:

North America, including Canada and Mexico;

Latin America; Europe;

Japan and South East Asia.

Still, a consultant is at one remove

from the day-today practice —

that is both his strength

and his weakness.

And so my viewpoint

tends more to be that of an outsider.”

broad worldview ↑

#pdw larger ↑ ::: Books by Peter Drucker ::: Rick Warren + Drucker

Books by Bob Buford and Walter Wriston

Global Peter Drucker Forum ::: Charles Handy — Starting small fires

Post-capitalist executive ↑

Learning to Learn (ecological awareness ::: operacy)

The MEMO they don’t want you to see

See rlaexp.com initial bread-crumb trail — toward the

end of this page — for a site “overview”

Amazon link: Toward The Next Economics and other Essays

These essays provide some very, very, very interesting brainroads to explore. They are attention-directing tools. Is there anything you should calendarize? — bobembry (site creator)

- Toward The Next Economics

See “The poverty of economic theory” continue

Productivity as the source of value is both a priori and operational, and thus satisfies the specifications for a first principle.

It would be both descriptive and normative, both describe what is and why and indicate what ought to be and why.

Marx, as the “Revisionists” of socialism around 1900 used to argue, was never fully satisfied with the Labor Theory of Value, but groped in vain for a substitute.

None of the great nonMarxist economists of the last hundred years, Alfred Marshall, Joseph Schumpeter, or John Maynard Keynes, was in turn comfortable with an economics that lacked a Theory of Value altogether.

But, as the Keynes anecdote illustrates, they saw no alternative.

Productivity as the source of all economic value would serve.

It would explain.

It would direct vision.

It would give guidance to analysis, to policy and behavior.

Productivity is both, man and things; both structural and analytical.

A productivity-based economics might thus become what all great economists have striven for: both a “humanity,” a “moral philosophy,” a “Geisteswissenschaft”; and rigorous “science.”

- Saving The Crusade: The High Cost Of Our Environmental Future

- Who Will Pay?

- Overlooked Facts of Life

- Making Virtue Pay

- An Environmental Crime?

- Third World Ecology

- Choosing the Lesser Evils

- Where to Start

- Business & Technology

- Anticipating and Planning Technology

- The Pace of Technology

- The Innovative Organization

- Responsibility for the Impact of Technology

- Difficulty of Prediction

- The Need for Technology Monitoring

- Conclusion

- A Historical Note

- Multinationals & Developing Countries: Myths and Realities

The best hope for developing countries, both to attain political and cultural nationhood and to obtain the employment opportunities and export earnings they need, is through the integrative power of the world economy.

And their tool, if only they are willing to use it, is, above all, the multinational company—precisely because it represents a global economy and cuts across national boundaries.

The multinational, if it survives, will surely look different tomorrow, will have a different structure, and will be “transnational” rather than “multinational.”

But even the multinational of today is—or at least should be—a most effective means to constructive nationhood for the developing world.

- What Results Should You Expect?: A User's Guide to MBO — full details (link to a PDF version) The Five Most Important Questions You Will Ever Ask About Your Nonprofit Organization

- Introduction

- Public service institutions are prone to the deadly disease of "bureaucracy"; that is, toward mistaking rules, regulations, and the smooth functioning of the machinery for accomplishment, and the self-interest of the agency for public service

- Misdirection, whether by the individual employee or by the administrator, is at the same time both easy and hard to detect

- Need objectives and concentration of efforts on goals and results—that is, management

- Too easy for the institution to mistake MBO procedures for the substance of both management and objectives

- MBO is both management by objectives and management by objectives.

- What is needed, therefore, are two sets of specifications—one spelling out the results in terms of objectives and one spelling out the results in terms of management.

- What are our objectives? What should they be?

- The clear realization that his agency actually has no objectives

- What passes for objectives are, as a rule, only good intentions

- The purpose of an objective is to make possible the organization of work for its attainment

- This means that objectives must be operational:

- capable of being converted

- into specific performance

- into work

- into work assignments

- Objectives in public service agencies are ambiguous, ambivalent, and multiple

- This holds true in private business as well, by the way

- Equally valid objectives are mutually incompatible or, at least, quite inconsistent

- Forces the administrator and his agency to a realization of the need to think and of the need to make highly risky balancing and trade-off decisions

- Priorities and posteriorities

- Public service institutions, almost without exception, have to strive to attain multiple objectives

- At the same time, each area of objectives will require a number of separate goals

- Yet no institution, least of all a large one, is capable of doing many things, let alone of doing many things well

- Institutions must concentrate and set priorities

- By the same token, they must make risky decisions about what to postpone and what to abandon—to think through posteriorities

- One basic reason for this need to concentrate is the communications problem, both within the institution and among the various external publics

- Institutions which try to attain simultaneously a great many different goals end up confusing their own members

- The confusion is extended twofold to the outside public on whose support they depend

- Another cogent reason for concentration of goals is that no institution has an abundance of truly effective resources

- We have all learned that money alone does not produce results

- Results require the hard work and efforts of dedicated people; such people are always in short supply

- Yet nothing destroys the effectiveness of competent individuals more than having their efforts splintered over a number of divergent concerns—there is nothing more frustrating or less productive than to give part-time attention to a major task

- To achieve results always requires thorough and consistent attention to the problem by at least one effective man or woman

- Finally, and this may be the most important factor, even a unitary, or a simple goal often requires a choice between very different strategies which cannot be pursued at the same time; one of them has to be given priority, which means that the other one assumes secondary status or is abandoned for an unspecified time

- To set priorities is usually fairly simple, or at least seems politically fairly simple

- What is difficult, and yet absolutely essential, is the risk-taking and politically dangerous decision as to what the posteriorities should be

- Every experienced administrator knows that what one postpones, one really abandons

- Therefore, essential to management by objectives in the public service agency is the establishment of priorities

- This requires first decisions concerning the areas of concentration

- Equally essential is the systematic appraisal of all services and activities in order to find the candidates for abandonment

- Goals of abandonment and schedules to attain these goals are an essential part of management by objectives, however unpopular, disagreeable, or difficult to attain they might be

- The great danger in large institutions, especially in public service institutions, is to confuse fat with muscle and motion with performance

- Specific goals, with specific targets, specific timetables, and specific strategies

- Implicit in this is the clear definition of the resources needed to attain these goals, the efforts needed, and primarily the allocation of available resources—especially of available manpower.

- A "plan" is not a plan unless the resources of competent, performing people needed for its attainment have been specifically allocated.

- Until then, the plan is only a good intention; in reality not even that

- How performance can be measured, or at least judged

- Unless results can be appraised objectively, there will be no results

- There will only be activity, that is, costs

- To produce results, it is necessary to know what results are desirable and determine whether the desired results are actually being achieved

- To think through the appropriate measurement is in itself a policy decision and therefore highly risky

- Measurements, or at least criteria for judgment and appraisal, define what we mean by performance

- For this reason it must be emphasized that measurements need to be measurements of performance rather than of efforts

- With measurements defined, it then becomes possible to organize the feedback from results to activities

- What results should be expected by what time?

- In effect, measurements decide what phenomena are results

- Identifying the appropriate measurements enables the administrator to move from diagnosis to prognosis

- He can now lay down what he expects will happen and take proper action to see whether it actually does happen

- The actual results of action are not predictable

- Indeed, if there is one rule for action, and especially for institutional action, it is that the expected results will not be attained

- The unexpected is practically certain

- But are the unexpected results deleterious?

- Are they actually more desirable than the results that were expected and planned?

- Do the deviations from the planned course of events demand a change in strategies, or perhaps a change in goals or priorities?

- Or are they such that they indicate opportunities that were not seen originally, opportunities that indicate the need to increase efforts and to run with success?

- Organized feedback leading to systematic review and continuous revision of objectives, roles, priorities, and allocation of resources must therefore be built into the administrative process

- What is management? what should it be?

- Understanding of the difficulty, complexity, and risk of these decisions

- The decision which MBO identifies and brings into focus:

- The decisions on objectives and their balance;

- On goals and strategies;

- On priorities and abandonment;

- On efforts and resource allocation;

- On the appropriate measurements,

- Are far too complex, risky, and uncertain to be made by acclamation

- To make them intelligently requires informed dissent

- Responsibility and commitment within the organization; to make possible self-control on the part of the managerial and professional people

- The desired result is willingness of the individual within the organization to focus his or her own vision and efforts toward the attainment of the organization's goals

- It is ability to have self-control; to know that the individual makes the right contribution and is able to appraise himself or herself rather than be appraised and controlled from the outside

- The desired result is commitment, rather than participation

- The right question is, what do you, given our mission, think the goals should be, the priorities should be, the strategies should be?

- What, by way of contribution to these goals, priorities, and strategies, should this institution hold you and your department accountable for over the next year or two?

- What goals, priorities, and strategies do you and your department aim for, separate and distinct from those of the institution?

- What will you have to contribute and what results will you have to produce to attain these goals?

- Where do you see major opportunities of contribution and performance for this institution and for your component?

- Where do you see major problems?

- Needless to say, it is then the task of the responsible administrator to decide

- What is true is that the two, subordinate and boss, cannot communicate unless they realize that they differ in their views of what is to be done and what could be done

- It is also true that there is no management by objectives unless the subordinate takes responsibility for performance, results, and, in the last analysis, for the organization itself

- Personnel decisions

- Management by objectives should always result in changing the allocation of effort, the assignment of people and the jobs they are doing

- It should always lead to a restructuring of the human resources toward the attainment of objectives

- On the contrary, the ruling postulate should be: every existing job is likely to be the wrong job and needs to be restructured, or at least redirected

- In reality, job substance changes with the needs of the organization; and assignments, that is, the specific commitment to results, change even more frequently

- Job descriptions may be semi-permanent

- However, assignments should always be considered as short-lived

- It is one of the basic purposes of managerial objectives to force the question, what are the specific assignments in this position which, given our goals, priorities, and strategies at this time, make the greatest contribution?

- Unless this question is being brought to the surface, MBO has not been properly applied

- It must determine what the right concentration of effort is and what the manpower priorities are, and then convert the answers into personnel action

- Similarly important and closely related are results in terms of organization structure

- If the work in organization over the last forty years has taught us anything, it is that structure follows strategy

- There are only a small number of organization designs available to the administrator

- How this limited number of organization designs is put together is largely determined by the strategies that an organization adopts, which in turn is determined by its goals

- Management by objectives should enable the administrator to think through organization structure

- Organization structure, while not in itself policy, is a tool of policy

- Any decision on policy, that is, any decision on objectives, priorities, and strategies, has consequences for organization structure

- The ultimate result of management by objectives is decision

- Both with respect

- To the goals and performance standards of the organization

- To the structure and behavior of the organization

- The test of MBO is not knowledge, but effective action

- This means, above all, risk-taking decisions

- Summary

- Filling out forms, no matter how well designed, is not management by objectives and self-control

- The results are!

- It is not the same thing as planning, but it is the core of planning

- The core of management

- It is the process in which decisions are made, goals are identified, priorities and posteriorities are set, and organization structure designed for the specific purposes of the institution

- It is also the process of people integrating themselves into the organization and directing themselves toward the organization's goals and purposes

- The Coming Rediscovery Of Scientific Management

- The True Taylor

- Flying in the Face of Ignorance

- As the World Learns

- Making Mental Work More Productive

- The Bored Board

- All over the Western world boards of directors are under attack and are being changed

- All these pressures assume that the board matters

- But there is little evidence to support this assumption

- Quite a few, including myself, are no longer willing to serve on boards, because we do not think we can contribute anything in such circumstances

- There are six essential functions only an effective board can discharge

- Who belongs on a board?

- After-Fixed Age Retirement Is Gone

- Science & Industry: Challenges of Antagonistic Interdependence

- Ways of Industry

- Tax Effects and Investments

- The Antitrust Bias

- Estrangement

- The Dangers

- The Philosophical Issue

- How To Guarantee Non-Performance — Public Service Program — full details (link to a PDF version)

- Commit any two of the following common sins and non-performance will follow

- Have a Lofty Objective

- To use such statements as "objectives" thus makes sure that no effective work will be done

- For work is always specific, always mundane, always focused

- Yet without work there is non-performance

- Try to Do Several Things at Once

- Splintering of efforts guarantees non-results

- Believe That "Fat Is Beautiful"

- It is even worse to overstaff than to overfund

- For overstaffing always focuses energies on the inside, on "administration" rather than on "results," on the machinery rather than its purpose

- It immobilizes behind a facade of furious busyness

- Don't experiment, be dogmatic

- Whatever you do, do it on a grand scale at the first try

- Otherwise, God forbid, you might learn how to do it differently.

- Successful application always demands adaptation, cutting, fitting, trying, balancing

- Always demands testing against reality before there is final total commitment

- Any new program, no matter how well conceived, will run into the unexpected, whether unexpected "problems" or unexpected "successes."

- Make sure that you will not learn from experience

- Do not think through in advance what you expect; do not then feed back from results to expectations so as to find out what you can do well, but also what your weaknesses, your limitations, and your blind spots are.

- Inability to Abandon

- They may become pointless because the need to which they address themselves no longer exists or is no longer urgent

- They may become pointless because the old need appears in such a new guise as to make obsolete present design, shape, concerns, and policies

- The only rational assumption is that any public service program will sooner or later—and usually sooner—outlive its usefulness, at least in its present form, in respect to its present objectives, and with its present policies

- A public service program that does not conduct itself in contemplation of its own mortality becomes incapable of performance

- Avoiding These Six Deadly Sins Is the Prerequisite for Performance and Results

- Yet, as everyone in public administration knows, most administrators commit most of these "sins" all the time and indeed all of them most of the time

- One reason is plain cowardice

- The Lack of Concern With Performance in Public Administration Theory

- But perhaps even more important than cowardice as an explanation for the tendency of so much of public administration today to commit itself to policies that can only result in nonperformance, is the lack of concern with performance in public administration theory

… Why and how this happened goes well beyond the scope of this essay, and the author is hardly qualified to answer the question.

There was no one single leader, no great figure, to put Japan on a new path.

Indeed, the historians will be as busy trying to explain what happened in the 1950s in Japan as they have been to explain what happened at the time of Meiji, eighty years earlier, when an equally humiliated and shocked Japan organized itself to become a modern nation and yet to remain profoundly Japanese in its culture.

One might perhaps speculate that the shock of total defeat and the humiliation of being occupied by foreign troops—no foreign soldier ever before had landed on Japanese soil—created a willingness to try things that had never been tried before, even though powerful forces in Japan’s history had urged and advocated them.

In respect to industrial relations, for instance, we know that there was no one single leader.

Yet the strong need of Japanese workers, many of them homeless, many of them discharged veterans from a defeated army, many of them without employment of any kind, to find a “home” and a “community” was surely an important factor, as was the strong pressure by workers on management to protect them from the pressures of the American occupation and its “liberal” labor experts to join left-wing unions and to become a “revolutionary” force.

The conservatism of the Japanese worker in the late forties and early fifties, but also the need of the Japanese worker to have a little security when his emotional, his economic, and in many cases his family ties had been severed, undoubtedly played a large part in the course Japan then took.

But why Japanese management found itself able to respond to these needs and in an effective form, no one yet knows.

Indeed, the Japanese “rules” could just as well be explained with purely “Western” teachings and traditions.

That business leadership, especially in big business, needs to take active responsibility and initiative for the national interest and must start out with what is good for the nation rather than what is good for business, was for instance preached in the West around 1900 by such totally un-Japanese leaders as Walter Rathenau in Germany, and Mark Hanna in the United States.

That an enemy that cannot be destroyed must be made into a friend and must never be “defeated” and humiliated was first thought around 1530 by the first modern political thinker, Niccolò Machiavelli.

And Japan’s embedding of conflict in a core of unity is also Machiavelli—the Machiavelli of The Discourses rather than that of The Prince.

Four hundred years later, in the 1920s, Mary Parker Follett, most proper of proper Bostonians, concluded again that conflicts must be made constructive by being embedded in a core of common purpose and common vision.

All these Westerners—Rathenau and Hanna, Machiavelli and Follett—asked the same questions: How can a complex modern society, a pluralist society of interdependence, a society in rapid change, be effectively governed?

How can it make productive its tensions and conflicts?

How can it evolve unity of action out of diversity of interests, values, and institutions?

And how, as Machiavelli asked, can it derive strength and cohesion from being surrounded by, and dependent on, a multitude of competing powers?

And why then did the West, and especially the United States, reject this tradition while Japan accepted it?

Again the scope of this question greatly exceeds this essay and the expertise of its author.

But one might speculate that the Great Depression and its trauma had something to do with it.

For before it, there was indeed leadership that subscribed to these values.

Both Herbert Hoover in the United States and Heinrich Bruening, the last Chancellor of a democratic Germany, represented a tradition that saw in the common interest of all groups the catalyst of national and social unity.

It was their defeat by the Great Depression—for instance, in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal—which ushered in a belief in “countervailing power,” in adversary relations, as leading to a compromise solution acceptable to all because it does not offend any one group too much, and therefore unites them on the least common denominator.

And surely the victory of Keynesian economics in the West, and especially in the United States, with their apotheosis of national government as omnipotent, omniscient, and able to control the national economy almost irrespective of what happens outside, had something to do with our forgetting the old adage of American politics that “Politics (and economic disputes) stop at the water’s edge.”

But this is speculation.

What is fact is that the “secret” behind Japan’s achievement is not a mysterious “Japan Inc.,” which belongs in a Hollywood Grade B movie anyhow.

It is perhaps not even the particular values of behavior that Japan has been practicing.

It may be that Japan, so far alone among major industrial countries, has asked the right questions:

What are the rules for a complex modern society, a society of pluralism and large organizations which have to coexist in competition and antagonism, a society that is embedded in a competitive and rapidly changing world and increasingly dependent on it?

Japan, as everybody knows, is a country of rigid rules and of individual subordination to a collective will.

… snip, snip …

Yet the most pervasive trait of all Japanese art is its individualism.

In every major period of artistic activity in the West there has been one universal style; we speak of the Hellenistic, of the Romanesque and the Gothic, the Renaissance and the Baroque.

But every period of great artistic activity in Japan has been characterized by diversity.

… snip, snip …

The perceptual in Japanese tradition largely underlies Japan’s rise as a modern society and economy.

It enabled the Japanese to grasp the essence, the fundamental configuration of things foreign and Western, whether an institution or a product, and then to redesign.

The most important thing that can be said about Japan as viewed through its art may well be that Japan is perceptual.

Conditions for survival

Preface

These twelve essays have a common author and a common point of view.

And though their topics are diverse, all are concerned with “social ecology,” and especially with the institutions—whether governments or organized science, businesses or schools—through which human beings attempt to realize values, traditions, and beliefs, and through which most people—and especially today’s educated people—gain access to livelihood and achievement, to careers, and to standing in society.

All these essays also share the conviction that sometime in the last decade there have been genuine structural changes in the “social ecology,” most pronounced perhaps in population structure and population dynamics in the developed countries;

but also in the role and performance of old-established and seemingly stable social bodies, such as government agencies or boards of directors, whether of businesses, hospitals, or universities;

in the interface between sciences and society; and

in fundamental theories that are still widely taught as “revealed truths.”

This is thus a “contemporary” book that addresses itself to current concerns such as the environment, retirement policies in aging populations, or the impacts of technology.

Yet, in selecting the pieces for this volume from my writings of the last ten years, I have excluded whatever might be called an article, that is, topical journalism, and have tried to confine myself to essays.

To my mind, the difference is not one of style or length or level, but of intent.

A good article catches the reality behind it, but it is concerned with the “here and now.”

The concerns to which these essays address themselves are those of the time in which they were written—our time.

The intention in every one was however to use the moment to gain understanding, to project, to see to the permanent through the transient.

This, I believe, is most apparent in the two essays that open and close the book, “Toward the Next Economics” and “A View of Japan Through Japanese Art.”

But the others are also informed by the same intent, and, I very much hope, convey to the reader the experience of self-knowledge, of immediacy, of direct understanding that a good portrait conveys, even though its subject may have been dead for centuries.

Most of the essays deal with concerns and challenges that are worldwide, or at least common to all developed non-Communist countries (and by and large to developed Communist countries as well).

But since they were written in America, by an American and for publication in American journals, they heavily use American examples or figures.

Only one piece however might be a little strange to non-American readers: the essay “Science and Industry: Challenges of Antagonistic Interdependence,” which was delivered to the 1979 annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

In writing this essay, I became aware of the extraordinary differences in the way in which various countries have structured the relationship between organized “big” science and society.

To a German, the friction between the two in today’s America must appear childish; to an Englishman or Japanese, on the contrary, the constant interaction between the two, however friction-laden, almost beyond belief.

And all three might find it hard to accept that in an America renowned for its pragmatism, organized “official” Science has for a century indulged itself in an extreme of virginal purity.

Yet the concern of the essay: the growing divergence between the mind-sets and value systems of the producers of scientific knowledge, the scientists, and the users and consumers of scientific knowledge, government and industry, is just as pronounced in all other developed countries and presents just as great a threat, especially to science.

Two of the essays deal, however, with a special area rather than with worldwide developments and problems: the last two essays, on Japan.

It is a country in which I have been interested for almost fifty years and which I have now visited more than a dozen times.

One fascination Japan holds for me is precisely that it is so different, that it is indeed sui generis.

It is no more “Asiatic” than it is “Western”—and yet sometimes it is both.

Few of what historians, sociologists, or theorists consider “universal laws” hold for Japan.

Alone of all civilizations, it knew no property in land (except by temples and the Emperor) until a hundred years ago; it knew only rights to the land’s products.

Alone of all civilizations, it voluntarily closed itself off from intercourse with the outside world for more than two centuries, while yet maintaining the liveliest interest in the arts, the learning, and the technology of the outside world, and the greatest respect for it.

Alone of all civilizations, it knew no wars, whether external or internal, for more than two centuries, even though being governed during that period by a military dictatorship and living under a code of martial ethics.

Above all, of all countries and civilizations I know of, Japan alone is accessible primarily through the eye rather than through the mind—and this despite being, for long centuries, from 1600 until the late nineteenth century, the country of the highest literacy rate.

The last essay in this volume thus represents an attempt at gaining through perception, via design and the visual arts, the same access to Japan and the same understanding that one gains to other nations and other cultures through analysis, whether of philosophers or of institutions.

Whether the attempt is successful, the reader must judge; but it is surely important—Japan is too important in the world today not to be perceived by us in the West.

And if this essay will move even a few Western—or Japanese—readers to look at Japanese paintings, either when next they visit a museum or in one of the many excellent art books now available, I—and they—will be amply repaid.

Essays 2 to 10 are reprinted in chronological order; it seemed the easiest and least contrived.

The opening essay is quite recent, however.

My long-time editor at Harper & Row, Cass Canfield, Jr., suggested it be put first, as it deals with a subject likely to be of most interest to the widest spectrum of readers and yet normally rendered unintelligible, even to the highly educated among them, by the economists’ propensity for technical jargon.

And Essay 11 is more recent still.

It was written after my last trip to Japan in the Summer of 1980, to answer all the many questions in the West about Japan’s sweep into industrial leadership, all the questions about the “secret” of Japan’s success.

And it seemed only logical then to put Essay 12, “A View of Japan Through Japanese Art,” next to Essay 11 and at the very end.

In an essay volume there is always a temptation to rewrite.

I have resisted it.

All I have done is to clear up a few ambiguities.

Where, for instance, an essay written in 1978 talked of “last fall,” I have changed this to “1977,” but have not changed anything else.

I think it only fair to let the reader decide how well the author’s opinions, prejudices, and predictions have stood the test of time.

One essay, however, I have had to revise extensively: that on “A View of Japan Through Japanese Art.”

Originally, this piece was my contribution to the catalogue “Song of the Brush,” which John M. Rosenfield of Harvard and Henry Trubner of the Seattle Art Museum edited for a major exhibition of Japanese paintings shown in 1979 and 1980 in New York; Cambridge, Massachusetts; Denver; San Francisco; and Seattle.

The essay contained numerous references to paintings shown in the exhibition and illustrated in the catalogue, which have had to be deleted.

The words that replace them are a poor substitute for pictures in a singularly beautiful catalogue, but the meaning still comes across, I trust.

This is my third volume of essays; the two earlier ones, containing selections spanning thirty years of writing each, were published respectively by Harper & Row in New York and by William Heinemann in London: Technology, Management & Society in 1970 and Men, Ideas & Politics in 1971.

Both volumes were well received and gained a wide circle of readership, in the original hard-cover editions and, more recently, as paperbacks.

I can only hope that this present volume will similarly renew many old and make many new friendships for me.

For to a writer, even the most critical reader is a friend.

— PETER F. DRUCKER

Claremont, California

New Year's Day, 1981

Toward the Next Economics

See “The poverty of economic theory” continue

In its four-hundred-year history economics has passed through four major changes in its world view, its concerns, its paradigms.

It is now in the throes of another, its fifth “scientific revolution.”

Economics today is very largely “The House that Keynes Built.” Even in the English-speaking world only a minority of economists are Keynesians in their specific theories.

But the great majority, perhaps even in the Communist countries, are Keynesians in their “mind-set,” in what they see and consider important, in their concerns, in their basic assumptions.

They tend to define themselves largely through their relationship to Keynesian economics, are “near Keynesians” or “non-Keynesians” or “anti-Keynesians.” Their terminology—Gross National Product, for instance, or money supply—assumes the economic aggregates on which Keynesian economics is based.

The views of economic activity, economic policy, economic theory which Keynes around 1930 propounded—or at least codified—have, fifty years later, become the familiar environment, the home-ground of economists regardless of persuasion.

The Keynesians may not muster the biggest battalions.

But they have occupied the commanding heights and thereby define the issues.

Yet both as economic theory and as economic policy Keynesian economics is in disarray.

It is unable to tackle the central policy problems of the developed economies—productivity and capital formation; indeed, Keynesian economics must deny that these problems could even exist.

Nor is it able to provide theory that can encompass, let alone explain, observed economic reality and experience.

And it has been proven to be entirely irrelevant to the economic needs and challenges of developing Third World countries, if not harmful to them.

Indeed, the two theoretical approaches which alone during these last ten or fifteen years have shown consistent predictive power are both incompatible with the Keynesian model: the theories of the Canadian-born Columbia University economist Robert Mundell, and those of the “rational expectations” school.

Mundell, after thorough empirical studies, concluded more than ten years ago that Keynesian policies do not work in the international economy.

He correctly predicted the failure of currency devaluations to correct the balance of payments, stem inflation, and improve competitive position.

The “rational expectations” school goes even further; it postulates that governmental, that is, macro-economic, intervention is not just deleterious; it is futile and ineffectual.

But these new approaches are equally incompatible with pre-Keynesian theories, whether NeoClassic or Marxist.

What makes the present “crisis of economics” a genuine “Scientific Revolution” is our inability to go back to the economic world view which Keynes overturned.

To be sure, most of the economic theorems, economic methodologies, economic terms found in the textbooks today will be found in the textbooks tomorrow.

They will only be reinterpreted—the way quantum physics reinterprets Newton’s Optics.

After all, Keynes did not discard a single theorem of classical economics.

He even retained “Say’s Law,” according to which savings always equal investments; it became a “special case.”

And one of the most advanced tools of modern economics, Input-Output Analysis, goes back to the first attempt at economic analysis, the Physiocrats’ Tableau Economique more than two centuries ago.

But as economic world view, or as economic system, the earlier theories—e.g., the disciplined orthodoxy of the “Austrians”—will not do.

What made Keynes so compelling fifty years ago even to a doubter (as I must confess myself to have been even then) was the new vision he forced on us; we suddenly had to see a whole new reality—and that reality is still with us and will not disappear.

The Next Economics will be “post-Keynesian.” It cannot ignore Keynes, but it will have to transcend him.

There may be no “Economics” in the future.

Totalitarian regimes, while greatly concerned with the economy, do not tolerate the postulate on which any discipline of economics must base itself: economic activity, though constrained and limited by non-economic rationality, concerns, and values, constitutes a discrete and separate sphere.

Totalitarian regimes cannot accept economic activity as autonomous, internally consistent, and “zweckrational” within its boundaries.

In a totalitarian regime, economics inexorably becomes a branch of accounting.

But if there is a future economics, it will differ fundamentally from the present one.

We do not yet know what the economic theories of tomorrow will be.

But we do know what the main problems, the main concerns, the main challenges will be.

We do not know the Next Economics; but we can outline its specifications.

The actual results of action are not predictable.

Indeed, if there is one rule for action, and especially for institutional action, it is that the expected results will not be attained.

The unexpected is practically certain.

But are the unexpected results deleterious?

Are they actually more desirable than the results that were expected and planned?

Do the deviations from the planned course of events demand a change in strategies, or perhaps a change in goals or priorities?

Or are they such that they indicate opportunities that were not seen originally, opportunities that indicate the need to increase efforts and to run with success?

These are questions the administrator in the public service agency rarely asks.

Unless he builds into the structure of objectives and strategies the organized feedback that will force these questions to his attention, he is likely to disregard the unexpected and to persist in the wrong course of action or to miss major opportunities.

Organized feedback leading to systematic review and continuous revision of objectives, roles, priorities, and allocation of resources must therefore be built into the administrative process.

To enable the administrator to do so is a result, and an important result, of management by objectives.

If it is not obtained, management by objectives has not been properly applied.

See: How to guarantee non-performance and What results should you expect? — a user’s guide to MBO

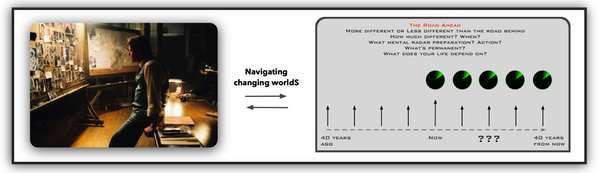

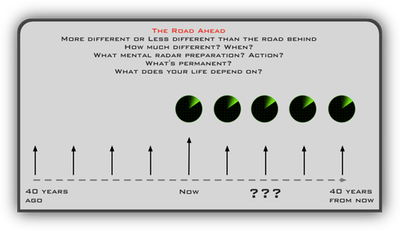

Information is not enough, thinking is needed — Dense reading and Dense listening and Thinking broad and Thinking detailed

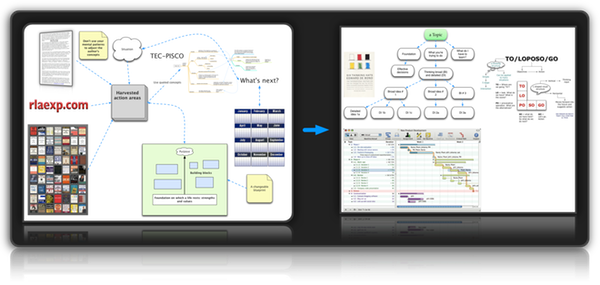

The following ↓ is a condensed strategic brainscape that can be explored and modified to fit a user’s needs

The concepts and links below ↓ are …

major foundations ↓ for future directed decisionS

aimed at navigating

a world constantly moving toward unimagined futureS ↓

YouTube: The History of the World in Two Hours

— beginning with the industrial revolution ↑ ↓

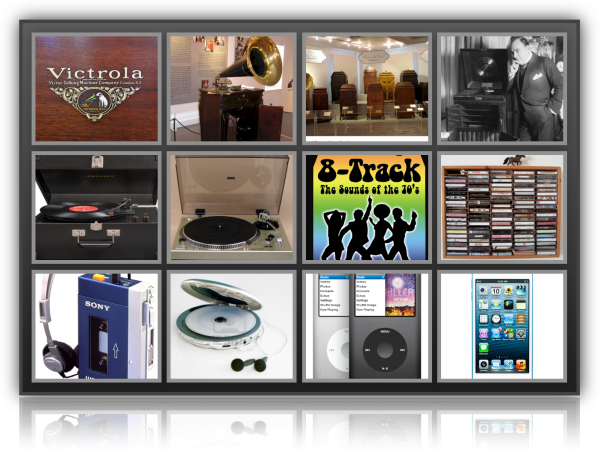

Management and the World’s Work

↑ In less than 150 years, management ↑ has transformed

the social and economic fabric of the world’s developed countries …

“Your thinking, choices, decisions are determined by

what you have seen” edb

Take responsibility for yourself and

don’t depend on any one organization ↑ ↓ (bread-crumb trailS below)

We can only work on the thingS on our mental radar ↑ at a point in time ↓

About time ↓ The future that has already happened

The economic and social health of our world

depends on

our capacity to navigate unimagined futureS

(and not be prisoners of the past)

The assumption that tomorrow is going to be

an extrapolation of yesterday sabotages the future — an

organization’s, a community’s and a nation’s future.

The assumption ↑ sabotages future generations — your children’s,

your grandchildren’s and your great grandchildren’s — in

spite of what the politicians say …

The vast majority of organization and political power structures

are engaged in this ↑ futile mind-set …

while rationalizing the evidence

The future is unpredictable and that means

it ain’t going to be like today

(which was designed & produced yesterday)

The capacity to navigate is governed by what’s between our ears ↑ ↓

When we are involved in doing something ↑

it is extremely difficult to navigate

and very easy to become a prisoner of the past.

We need to maintain a pre-thought ↓

systematic approach to work and work approach ↓

Click on either side of the image below to see a larger view

based on reality →

the non-linearity of time and events

and the unpredictability of the future

with its unimagined natureS. ↓ ↑

(It’s just a matter of time before we can’t get to the future

from where we are presently)

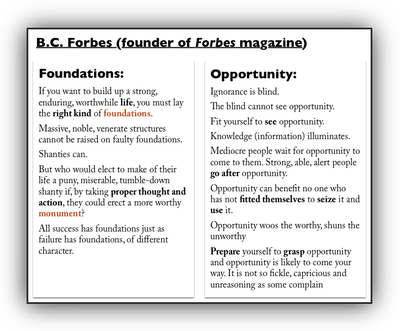

Foundations and opportunities ::: larger view ↓

Intelligence and behavior ↑ ↓ ← Niccolò Machiavelli ↑ ↓

Political ecologists believe that the traditional disciplines define fairly narrow and limited tools rather than meaningful and self-contained areas of knowledge, action, and events … continue

❡ ❡ ❡

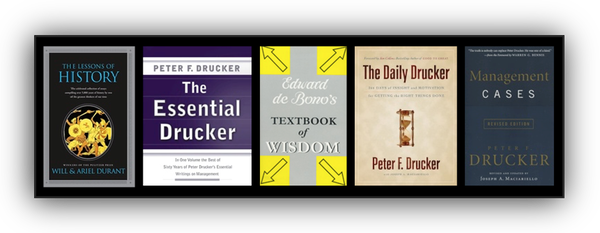

Foundational ↑ Books → The Lessons of History — unfolding realities (The New Pluralism → in Landmarks of Tomorrow ::: in Frontiers of Management ::: How Can Government Function? ::: the need for a political and social theory ::: toward a theory of organizations then un-centralizing plus victims of success) ::: The Essential Drucker — your horizons? ::: Textbook of Wisdom — conceptual vision and imagination tools ::: The Daily Drucker — conceptual breadth ::: Management Cases (Revised Edition) see chapter titles for examples of “named” situations …

What do these ideas, concepts, horizons mean for me? continue

Society of Organizations

“Corporations once built to last like pyramids

are now more like tents.

Tomorrow they’re gone or in turmoil.”

“The failure to understand the nature, function, and

purpose of business enterprise” Chapter 9, Management Revised Edition

“The customer never buys ↑ what you think you sell.

And you don’t know it.

That’s why it’s so difficult to differentiate yourself.” Druckerism

“People in any organization are always attached to the obsolete —

the things that should have worked but did not,

the things that once were productive and no longer are.” Druckerism

Why Peter Drucker Distrusted Facts (HBR blog) and here

Best people working on the wrong things continue

Conditions for survival

Going outside

Making the future — a chance for survival ↑

“For what should America’s new owners, the pension funds,

hold corporate management accountable?” and

“Rather, they maximize the wealth-producing capacity of the enterprise”

Search for the quotes above here

Successful careerS are not planned ↑ here and ↓

What do these issues, these challenges mean for me & … — an alternative

Exploration paths → The memo they don’t want you to see ::: Peter Drucker — top of the food chain ::: Work life foundations (links to Managing Oneself) ::: A century of social transformation ::: Post-capitalist executive interview ::: Allocating your life ::: What executives should remember ::: What makes an effective executive? ::: Innovation ::: Patriotism is not enough → citizenship is needed ::: Drucker’s “Time” and “Toward tomorrowS” books ::: Concepts (a WIP) ::: Site map a.k.a. brainscape, thoughtscape, timescape

Just reading ↑ is not enough, harvesting and action thinking are needed … continue

Information ↑ is not enough, thinking ↓ is needed … first then next + critical thinking

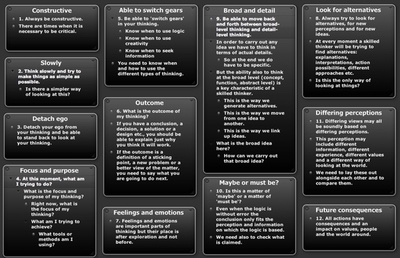

Larger view of thinking principles ↑ Text version ↑ :::

Always be constructive ↑ What additional thinking is needed?

Initially and absolutely needed: the willingness and capacity to

regularly look outside of current mental involvements continue

bread-crumb trail end

|

![]()