Managing for the Future

by Peter Drucker — his other books

See rlaexp.com initial bread-crumb trail — toward the

end of this page — for a site “overview”

Amazon link: Managing for the Future

See about management

Preface

About a year after my 1985 book, The Frontiers of Management, had come out, I received the following letter:

“I am the CEO of a still fairly small but fast-growing specialty-chemicals company.

I try to read five or six of your chapters every weekend, and ask my senior associates to do likewise.

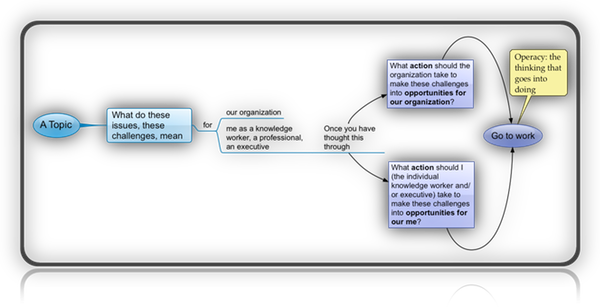

When I finish one of the chapters I then ask myself in writing:

What does this chapter mean for me as a senior business executive?

What does it mean for my colleagues on the management team?

What does it mean for the company?

What action does it imply—for me, the management team, the company?

What opportunities does it identify for us?

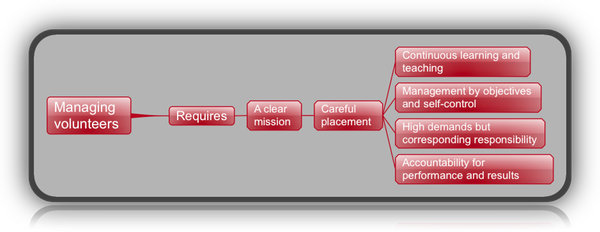

See concept of mission

What changes in goals, strategies, policies, structure, might it point to?’

We then discuss our respective answers at one of our management meetings.

And six months later we discuss the same answers again to see what actions we have actually taken and how they have worked out, but also what actions we should have taken and might still undertake.

Of course, a good many of your chapters do not directly apply to us; they lead to understanding rather than to action.

But a good many, again and again, stimulate us to do something or to stop doing something.

And the most valuable ones are the chapters that make me say: ‘Of course, I have known this all along.

Why haven’t I acted on it?’

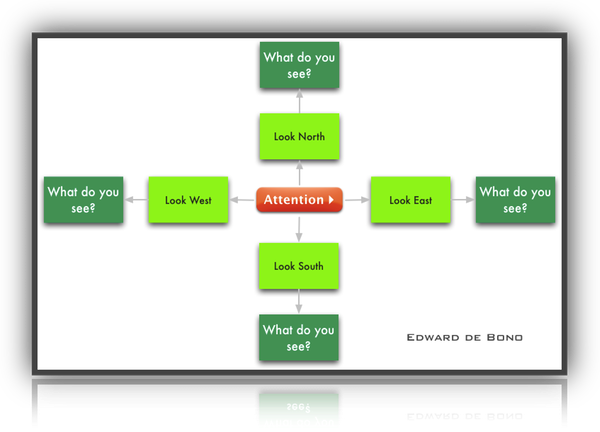

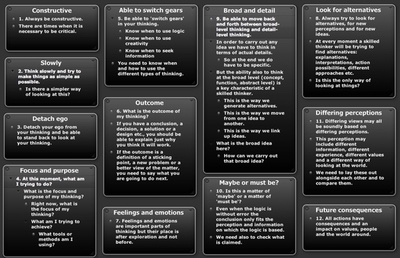

Larger view of challenge thinking (below) and an alternative — operacy

Note the fog and reflection ↓

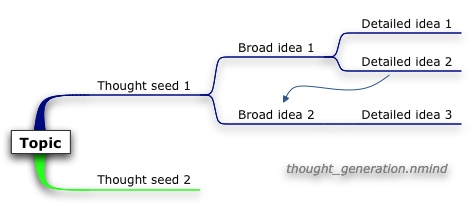

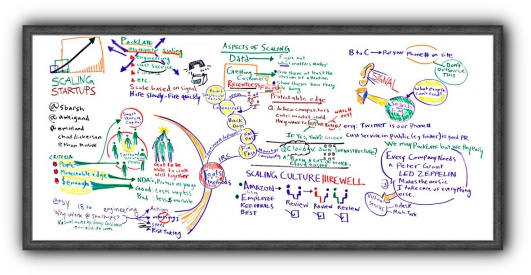

Dense reading and Dense listening and Thinking broad and Thinking detailed

Questions ::: Thinking canvases

The chapters in this book cover a wide range of topics, and they were written over a five-year period.

The individual chapters were not “planned” to fill a spot on an outline sketched out five years ago.

But each was most definitely designed from the beginning to address one of the dimensions of the executive’s world: the economy and economics; people; management; organization—both outside and inside the executive’s particular enterprise.

In addition, each chapter was planned from the beginning to achieve two purposes.

One: to explain to executives immersed in the demands of their own tasks and their own enterprise to understand the rapidly changing world in which they work and produce results.

The other was to stimulate them to action and to provide tools for effective action.

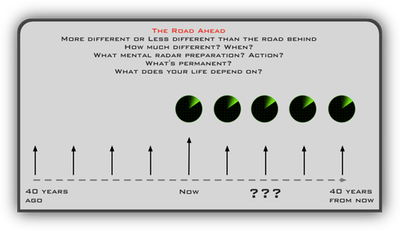

The executive’s world has been turbulent for as long as I can remember—I started work two years before the 1929 crash!

It surely has always been turbulent, but never as much as in these past few years—or in the years immediately ahead.

Only a few short years ago, for instance, we worried about inflation and about the ascendancy of all kinds of new financial superpowers: global banks, transnational brokerage houses, junk-bond kings, takeover tycoons, and the like.

Inflation is, of course, still a danger—and will remain one as long as governments pile up huge deficits.

But executives in the ‘90s are more likely to be worried by financial stringencies and credit crunches—that is, by the typical deflation symptoms.

The monetary giants of yesterday are everywhere in full retreat and mired in scandal.

The international economy of 1992 also bears almost no resemblance to that of 1980 or 1981 (when Japan still ran a trade deficit, the European Economic Community was still pie in the sky, and lending, billions to Brazilian generals still seemed to be the truly conservative thing to do).

So, every chapter in this book tries to create understanding of what changes are ahead and what they mean for the economy, people, markets, management, the organization.

Every one of the chapters tries to create the understanding the executive needs to manage for tomorrow rather than for yesterday.

But every chapter was also designed from the beginning to stimulate action—to identify new opportunities; to point out areas where changes—in process and product, policies, markets, and structure—might be needed; where and what to do and where and what to stop doing.

The five years during which the chapters of this book were being written were years of unprecedented political upheaval.

The earliest chapter in this book was written in August 1986; in the same week I wrote the first draft of what was published—in early winter of 1989—as Chapter 4 in my book The New Realities under the title “When the Russian Empire Is Gone”—an essay in which I predicted the inevitable failure of Mr. Gorbachev’s economic policies, the equally inevitable collapse of communism, and the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

But the chapter I wrote that week for this book—it is Chapter 22—bears the title “How to Manage the Boss.”

The most recently written chapter in this book, Chapter 24, was done almost exactly five years later, in August 1991 in the week after the Communist hardliners’ putsch against Mr. Gorbachev had failed.

Its title, however, is “The New Japanese Business Strategies.”

This book, in other words, focuses on executives, in their organizations and in their work.

“The show must go on” is its motto—and management’s “show” is effective action for results.

To help executives act and to produce results, to help them perform—in a turbulent, dangerous, fast-changing economy, society, and technology—that is the purpose and mission of this book.

- Preface

- Interview: Notes on the Post-Business Society

- Economics

- The futures already around us

- The poverty of economic theory

- The transnational economy

- From world trade to world investment

- The lessons of the U.S. export boom

- Low wages: no longer a competitive edge

- Europe in the 1990s: Strategies for survival

- U.S.-Japan trade needs a reality check

- Japan’s great postwar weapon

- Misinterpreting Japan and the Japanese

- Help Latin America and help ourselves

- Mexico’s ace in the hole: the maquiladora

- People

- The New Productivity Challenge

- The mystique of the business leader

- Leadership: More Doing Than Dash

- People, work, and the future of the city (Social impacts of information)

- The fall of the blue-collar worker

- End work rules and job descriptions

- Making managers of communist bureaucrats

- China's nightmare: No Jobs for the Millions

- Management

- The organization

- The governance of corporations

- Four marketing lessons for the future

- Tomorrow’s company: dressed for success

- Company performance: five telltale tests

- Market standing

- Innovative performance (Early Warning)

- Productivity

- Liquidity and Cash Flows

- Profitability

- No Precise Readings

- R&D: the best is business driven

- Sell the mailroom: Unbundling in the '90s

- The 10 rules of effective research

- The trend toward alliances for progress

- A crisis in capitalism: Who's in charge?

- The emerging theory of manufacturing

- Afterword: 1990s and beyond — calendarize

- The changing world economy

- But New International Dynamics Do Matter

- In the East Too

- A new international economic order is emerging

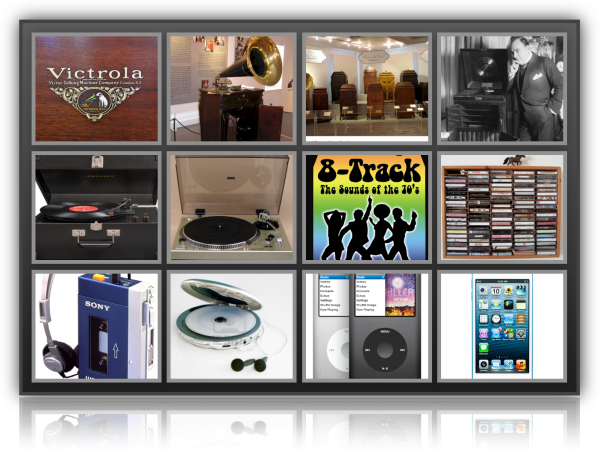

- Finance, a Model for the Future: Adapt or Die

- Institutional Finance Must Change Too

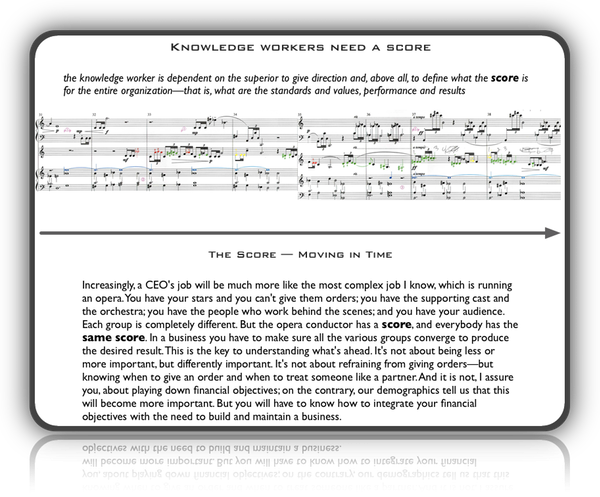

- The knowledge society

- Information Matters

- Information Means a New Type of Management

- Changing Society: The Decline of the Servant

- the Farmer

- and the Worker

- The Learning Society is Taking Over

- Most Education Does Not Deliver Knowledge

- So Organization Must Do It Themselves

- Innovation and entrepreneurship

- Two practices (not science or art)

- Companies need the practice of innovation to survive and prosper

- Cannot be confined to start-ups and new businesses

- Lessons from the Nineteenth Century’s Innovative Climate

There is one great difference between the innovative climate of the last 20 years and the late nineteenth century.

Our rate of innovation (social as well as technical, that is just as important) is equally rapid.

But practically all the institutions, business or other, of the nineteenth century were new: they emerged in the 50 or so years between 1865 (the year of Perkins’s first aniline dye, Siemens’s first dynamo) and 1914, when the First World War paralyzed the entrepreneurial energies of the West.

During that period a new institution, a major invention or innovation emerged on average more often than once a year.

Some of them led to the founding of new industries.

But they did not displace existing institutions.

They emerged, as it were, into a vacuum.

Thus, the Home Office set up British local government in 1856 from scratch.

In the same decade the first modern U.S. university was founded.

Today the task is different: we have to learn to make existing institutions capable of innovation.

We know what is needed, and it is relatively uncomplicated, although that does not mean it is easy.

But if existing institutions cannot learn to innovate, the social consequences will be almost unbearably severe.

- Innovation matters because ours is a knowledge-base society

- Innovation means abandoning the old

- The zero-based audit

- Innovation means looking on change as an opportunity

- Innovation is work above all

- Organize to undertake systematic entrepreneurship and purposeful innovation

- Personal effectiveness

- In the light of what skills and abilities will an executive need to be effective in the next years?

- The old skills

- The new skills

- Management by Going Outside

- Find out the Information You Need to Do Your Job

- Build Learning into the System

- There are enormous opportunities, because change is opportunity

Interview. Notes on the Post-Business Society

Q: You have written that there is a profound sense of unreality about both politics and economics today.

What do you mean?

A: Most of what we assume axiomatically no longer fits our reality, lending a surreal air to our work and lives.

The world seems to have dissolved into a series of media events that appear either bigger than reality or totally formless.

This is especially true in political life, where we have entered terra incognita.

The reason for the present confusion is that, at some point between 1965 and 1973, we passed a “great divide” into the next century, leaving behind the creeds, commitments and alignments that had shaped politics for a century or two.

At the most profound level, the Enlightenment faith in progress through collective action—"salvation by society,” which had been the dominant force of politics since the eighteenth century—was thoroughly dashed.

American Democrats of Great Society lineage are no longer true believers, and, neither the nominally socialist Francois Mitterrand, nor even Mikhail Gorbachev, espouse the faith any longer.

In the rise of Western ideas, especially Marxism, to world dominance, the West’s superiority in machines, money, and guns was probably less important than the promise of salvation by society.

Now that is gone.

Yet, the only effective nonideological counterforce of political integration—interest bloc politics—is also finally spent.

Witness the demise of Jim Wright, the factional crisis and collapse of the Liberal Democratic Party in Japan, and the precarious political coalitions of Europe’s economic anchor, Germany.

The last such divide was crossed a century earlier, in 1873.

That Liberal century, in which the dominant political creed was laissez-faire, began in 1776 with Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations and ended with the nonevent of the Vienna stock market crash and the short-lived panics in Paris, London, Frankfurt, and New York in 1873.

Although the economy of the Western world had recovered 18 months later, politics—which would now seek security and protection from the upheavals associated with the Industrial Revolution—was changed forever.

Within 10 years of the Vienna crash, German Chancellor Otto Von Bismarck had invented national health insurance and compulsory old-age insurance.

Within 20 years, Marxist socialists had become the largest political party in every major country of continental Europe.

In the U.S., the 1880s brought a shift away from the unrestricted market to the Interstate Commerce Commission for regulation of the railroads, the antitrust laws and the first state laws regulating securities.

The 1880s also brought about the first distinctly “antibusiness” movement in the U.S., the populists, and their successful “socialization” of the local power company in Lincoln, Nebraska—only the second city in the Western world to do so, after Vienna.

Following these early events, the “progressive” cause of government control of the economy and direction of society became widespread.

The great political debate of the last century was not over the “welfare state.”

Instead, the debate was over unrestricted government power, as we saw in the case of Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini, and Mao, versus democratic and legal constraints on the power of the state as we saw in the U.S., Japan and postwar Europe.

The period 1968-73 is a divide fully comparable to 1873.

Whereas 1873 marked the end of laissez-faire, 1973 marked the end of the era in which government was the “progressive” cause, the instrument embodying the principles of the Enlightenment.

The “oil shock,” the floated dollar, and the student rebellions across the West set us adrift from the century in which we had lived.

To be sure, the slogans of the welfare state persist, but they do not provide a guide for action or motive power.

They are all that remain, like the smile on the Chesire Cat, when all else is gone.

Q: After the turbulence of “creative destruction” that accompanied the Industrial Revolution, a whole set of mechanisms—whereby the state absorbed social risk—were set in place.

As government’s role as insurer against social risk grew, it came to be seen as an impediment to the new wave of innovation, the “entrepreneurial burst” associated with the bioengineering and Information Revolutions and the internationalization of the economy.

Have we just completed a long trend toward a culture of security that is now being cast off in favor of a culture of risk?

Isn’t that the common thread that runs through the post-1973 era of Reagan-Thatcher-Gorbachev?

A: First of all, let’s be clear that government is still growing.

Ronald Reagan increased the size of the federal budget more than any predecessor.

And, while we have deregulated the airlines, we have also made drug testing mandatory.

Drug testing is far more interventionist than airline regulation.

The state is hardly withering away.

Risk and security are not in opposition, but parallel.

After all, Social Security is an invention of the nineteenth century’s industrial “entrepreneurial burst.”

It was created precisely because there was so much risk being generated.

And, I am sure new forms of security will be created to cope with the risks of the current entrepreneurial period.

What might the new forms of security be?

One response, resulting from the present economic upheaval, is to me the most significant development of the late twentieth century: the emergence of the job as a property right.

These last years have seen a spate of court rulings sharply limiting the traditional right of the employer to terminate employees at will, even if they have no contract.

The risk of dislocation now means losing the security of the position a person has achieved after working 22 years at General Electric.

If this person was the managing engineer, he once knew that if he made steam turbines yesterday he would make them tomorrow.

And he knew that when GE controlled 45 percent of the market he did not have to work too hard to stay where he was.

There would always be a job for him and raises ahead.

Now, that person knows GE may move out of steam turbines altogether, at any time.

A young person he has never heard of could come up with a gadget tomorrow that would make GE’s 45 percent control of the market obsolete.

That is an outrage to this vested employee.

His illusion of security has been exploded.

He had come to accept his job as a right, his position as a law of nature.

So he sues to keep that job, seeking to redefine it as his “property.”

In human history, nothing has had greater impact than the redefinition of property rights.

That is fundamental to the transformation of social orders.

In the transition from laissez-faire to the welfare state, the important property became the commercial wealth created by trading merchants; it was no longer land.

The redefinition of the job as property right is largely a reaction to today’s great wave of entrepreneurialism.

Q: In the perpetually innovating “knowledge society” characterized by economic instability, isn’t education both the mechanism of mobility and security, a kind of mobile security that allows one to move between careers and different organizations?

A: The right kind of education is a new form of security.

However, our schools have yet to accept the fact that in the “knowledge society,” the majority of people make their living an organization in which they have to be effective.

Yet, this is the exact opposite of what our educational system assumes.

The “knowledge society” is a society of large organizations—government and business — that necessarily operate on the flow of information.

In this sense, all the advanced societies of the West have become “post-business.”

Business is no longer the main avenue of advancement in society.

Career opportunity increasingly requires a university diploma.

The center of gravity has shifted to the knowledge worker.

Yet, no educational institution—not even the graduate school of management—tries to equip students with the elementary skills that would make them effective as members of an organization: the ability to present ideas orally and in writing; the ability to work with people; the ability to shape and direct one’s own work, contribution and career.

The “educated person” ought to be the new archetype of the post-business society.

Q: What new economic realities have made our economic thinking outmoded?

A: There is a new configuration to economic life today which confounds all the old analytical categories.

For the first time, the raw material economy has become uncoupled from the industrial economy.

For the non-Communist world, at least, the raw material economy has become marginal.

For almost a decade now, the raw material economy has been in a deep depression, yet the industrial economies are booming.

In all past business cycles, a slump in food and raw materials has been followed within 18 months by a crisis in the industrial economy.

Not this time.

I think there are a couple of related reasons for this uncoupling.

There is a worldwide surplus of farm products, caused by the enormous expansion of agricultural production in the developing world.

While that glut has caused farm income in the U.S., for example, to drop by two-thirds in some regions between 1984-87, it has had little effect on the overall spending power in the economy because the farm population is now insignificantly small.

As important, manufactured products contain far less raw materials than they used to.

In the 1920s, for example, raw materials and energy comprised 60 percent of the cost of the key product at the time, the automobile.

The key product of our time, the microchip, has a raw material and energy content of less than 2 percent.

Japan increased its industrial production between 1965 and 1985 two and a half times, but it barely increased its raw material and energy consumption at all!

Manufacturing is also becoming uncoupled from labor.

In 1988, the same volume of goods could be produced as in 1973 with only two-fifths the blue-collar man hours.

Investment used to follow trade.

Now, investors put production facilities anywhere in the global market instead of producing at home and exporting.

They can now just as easily produce abroad and then import back home.

They do research where there are researchers and design where there are designers.

The Pontiac Le Mans, for example, was designed in Germany and built with Japanese parts in Korea.

Honda makes cars in America and exports them back to Japan.

The “real” economy of goods and services has been uncoupled from the money economy.

Every day, the London Interbank market turns over 15 times the amount of Eurodollars, Euroyen, and Euromarks needed to finance world trade.

Ninety percent of the transnational economy’s financial transactions serve no “economic function” in terms of production.

Yet, a substantial activity of every transnational firm must involve managing their inherently unstable foreign exchange exposure.

The transnational money economy is no longer the “veil of reality” as Marx once said.

It is the reality to which goods and services are subservient.

Complementary and competitive trade have been replaced by adversarial trade.

In Adam Smith’s eighteenth century, trade was complementary: England sold wool to Portugal for wine it could not produce; Portugal sold the wine for wool it could not produce.

In the mid-nineteenth century, trade became competitive: Germany and the U.S. competed to sell chemicals to each other and to the world.

Complementary trade sought a partnership.

Competitive trade sought a customer.

Adversarial trade aims to dominate entire industries.

While competitive trade was fighting a battle, adversarial trade seeks to win the war by destroying the enemy’s army and capacity to fight.

Protectionism is not an answer to adversarial trade.

As far as I can see, only reciprocity—where each country enjoys the same access to the other country’s market and no more—is the only trading relationship that will avoid degeneration into protectionism.

And I suspect that reciprocity will function most effectively in regional units—the EEC, Japan-Far East, North America—so that the smaller economies will have a large enough market to generate enough production and sales to sustain themselves.

Q: Let’s talk about economic theory.

Why do we find it so difficult to conceptualize the workings of the economy these days?

A: For 60 years, mainstream economic policy in the West was based on the ideas of John Maynard Keynes.

Now, the assumptions of his concepts are obsolete.

Keynes could not see the shape of the global economy, which would undercut his theories, until the end of his life in the late 1940s.

Indeed, before he died, Keynes admitted his theory of the economy could no longer work.

But it was too late, the Keynesians were already in full control.

Under the influence of those Keynesians, economic theory still assumes that the sovereign state is the predominant unit of economic life, and thus the only effective unit for economic policy.

In actuality, there are four economies, each, as the mathematicians would say, a “partially dependent variable”—interdependent but not controlled by each other.

First, there is the economy of the nation;

increasingly, however, power is shifting to the region—North America, the European Economic Community, and the Far East region grouped around Japan;

there is also an almost autonomous world economy of money, credit, and investment flows;

finally, there is the economy of the transnational enterprise, which views the world as one market.

With OPEC and Nixon’s floating of the dollar in the mid-1970s, the world economy changed from international to transnational.

The transnational economy is shaped mainly by the dynamic of money flows rather than goods and services; sovereign nation-states react to, rather than initiate or control, events in the global capital markets.

The traditional factors of production—land, labor and even money, because it is so mobile—no longer assure a particular nation competitive advantage.

Rather, management has become the decisive factor of production.

And the goal of management in a transnational enterprise that operates in one world market is maximization of market share, not the traditional short-term “profit maximization” of the old-style corporation.

Q: So, Keynes was only viable as long as one force—the national economy—was a sovereign entity that had some control over its internal situation and could calculate its policy effect in the international economy.

Now, that is gone.

A: As long as there was some reality to the nation-state, Keynes’ “perfect gas” theory of the economy seemed to work.

He felt that if the national government could control the temperature and pressure of the macroenvironment through money, credit and interest rates, individuals and firms—the micro-economy—would react predictably.

But this theory of how an economy works cannot explain any of the main economic events of the last 15 years.

In order to promote exports and create jobs in the mid 1970s, Jimmy Carter pushed down the value of the dollar, vis-àˆ-vis the yen, from 250 to 180.

Exports boomed but unemployment continued to rise, which should have caused deflation.

Instead, inflation skyrocketed as high as 14 percent.

When Reagan came to office, he raised interest rates to halt inflation.

He succeeded, but drove the dollar back up to 250 against the yen, damaging American exports and creating an unprecedented market in the U.S. for Japanese products.

According to all available theory, that should have caused more unemployment; instead, unemployment rates under Reagan fell to the lowest level in decades, with acute labor shortages appearing in some areas by 1989.

When Reagan tried to adjust the dollar “slightly” in the fall of 1985, it went unexpectedly into freefall down to 125.

Instead of massive “flight from the dollar,” which available theory predicted, the main holders of the dollar—Japan, Taiwan, West Germany, and Canada—who had placed large amounts of their dollar reserves in U.S. debt obligations, actually increased their lending to the U.S.

To confound theory further, the price of raw materials, from Danish butter to Arab petroleum—which the Japanese pay for in dollars—plummeted.

That further depressed worldwide commodity prices.

Additionally, the devaluation of the dollar should have raised the price of Japanese goods in the U.S. Instead, the Japanese firms did something unprecedented: they absorbed a 50 percent cut in profits to maintain their share of the U.S. market.

To compensate for that cut in foreign profits, Japanese companies sharply raised prices at home.

But instead of triggering a recession, Japan experienced the largest consumer binge in its history.

Presumably, it was the maturing baby boomers emulating their consumer counterparts elsewhere in the West that frustrated the expectation that higher prices would curb spending but raise savings.

What has happened?

First of all, it turns out that the microeconomy—the decisions of the multitude of individuals and firms—has sabotaged the supposedly controlling macroeconomy of the sovereign nation.

The servants are in control of the master.

For example, Keynes assumed that the “velocity of the turnover of money”—how fast individuals spend their money—was a social habit that remained unchanged over long periods of time.

But, every time this assumption has been put to the test it has been proven wrong.

Indeed, the individual’s ability—not the government’s ability—to control the rate of spending money explains Jimmy Carter’s policy disaster.

Consumers did not follow the textbook by spending and creating jobs; they hoarded instead.

In a rapid reversal, American consumers then increased their spending during the Reagan years, which explains why his policies worked in expanding the economy even with a huge trade deficit.

Similarly, the Japanese firms frustrated attempts to balance trade because they sought “market maximization” instead of “short-term profit maximization,” thus confounding what they were “rationally” expected to do according to present economic theory.

In the world economy, economic rationality means something different than it meant in the national economy.

As the Japanese have understood, “sales” in the world market are returns on long-term investment: What matters is the total return over the lifetime of the investment, and the return over time depends on monopolizing market share.

And, of course, there is no room in contemporary economic theory for technology and innovation.

Yet, entrepreneurship, invention and innovation can profoundly alter the economy in a very short time.

So, both individuals and firms, especially transnational firms, sabotage the attempted macroeconomic policies of nation-states that are no longer sovereign.

The new realities have turned Keynes on his head.

Keynes was the last great synthesizer of economic thought.

Without a new synthesis that presents a model of how the “four economies” interact to create economic reality, we may be at the end of economic theory.

And without economic theory there can be no economic policy—no foundation for governmental action to manage the business cycle and economic conditions.

Any functioning economic theory of the future must integrate the macroeconomy of money, credit and interest rates, and the microeconomic decisions about how firms and individuals spend money.

Such a theory must also account for the dynamic of entrepreneurship and innovation.

We may well conclude that the new reality means we can no longer control the economic “weather” of recession and boom cycles, unemployment, savings and spending rates, but only the “climate”—avoiding protectionism, or educating the working population to function in a knowledge society.

In short, preventive medicine instead of blind attempts at short-term fixes.

[1989]

3. The Transnational Economy

To maintain a leadership position in any one developed country, a business—whether large or small—increasingly has to attain and hold leadership positions in all developed markets worldwide.

It has to be able to do research, to design, to develop, to engineer and to manufacture in any part of the developed world, and to export from any developed country to any other.

It has to go transnational.

This new need largely explains the worldwide boom in transnational direct investments.

The front-runners are the British.

Since 1983, British companies have spent at least $25 billion on acquiring American businesses—the most massive British thrust into the world economy since Victorian times.

The West Germans may not be far behind.

Unlike the British they concentrate, however, on smaller, closely held companies.

And, contrary to popular belief, many of the U.S. multinationals are advancing rather than retrenching in Western Europe and in Japan.

There is also a transnational push of small and medium-sized businesses.

The vehicle often is not an acquisition or a financial transaction but what the Germans call “a community of interest”: a joint-venture, research-pooling, joint-marketing, or cross-licensing agreement.

A small specialty producer in the American Midwest with world leadership in one component of single-cylinder gasoline engines had facilities only in the U.S. seven years ago.

Now owns three plants in Japan that directly supply Japanese motorcycle manufacturers.

But the firm also has entered into joint venture in the Midwest with a similarly small Japanese specialty producer of another component of single-cylinder engines.

The Japanese supply capital and technology and the Americans supply management and marketing.

Banding Together

Four small, closely held firms, an American, a Dutch, a German and a Japanese—each a leader in one narrow line of chemical solvents—have merged their separate research labs with the lab of an American university with expertise in the solvents field.

Only by banding together do they have the $200 million in sales needed to support a decent research budget in a rapidly changing technology.

And then there is the Belgian producer of processed meats—the largest producer in its specialty lines within the Common Market but still with sales of only about $60 million a year.

Early this year, the firm and an even smaller Spanish meat processor formed a partnership.

The firms stay independent.

But the Spaniards will do all the labor-intensive manufacturing for both firms and the Belgians the research, the product development and the marketing.

Such communities of interest are by no means confined to small and medium-sized businesses.

Two of the world’s largest companies—GM and Toyota—are in such a partnership.

The big plant in Fremont, California, is a GM plant.

But it is managed by Toyota.

And it produces cars under both the Toyota and the GM marques.

The world’s largest heavy-engineering company with $15 billion in annual sales will start operations next January.

It is being formed by merging the electrical-apparatus businesses of Sweden’s ASEA and Switzerland’s Brown Boveri.

Each of these big, old companies has leadership in important European markets.

But only by combining their electrical-apparatus businesses in a joint venture can they hope to become a factor in North America and the Far East.

Going transnational is not confined to manufacturing firms.

It is becoming imperative for any business that aims at a leadership position any place in the developed world.

The only exceptions are businesses that by the nature of their activity are confined to a locality or region—hospitals, schools, cemeteries, electric-power suppliers—and governmental monopolies.

Banking and finance have, of course, become increasingly transnational ever since the major New York banks went worldwide in the ‘6os.

Now major insurance companies, foremost among them Germany’s Allianz, are aggressively expanding across national and continental boundaries.

British, German and Dutch book publishers have bought major U.S. publishing houses—but U.S. publishers have similarly moved aggressively into British book publishing.

Again, a good deal of the development is not “big-company stuff” and is based on a community of interest.

A highly specialized, medium-sized American asset-management firm has, for instance, recently formed a partnership with an equally specialized, medium-sized Japanese asset-manager and a somewhat larger financial house in London.

Each firm remains independent, but the American firm manages all U.S. investments for the three partners; the Tokyo firm, all Japanese investments; and the British firm, all investments in Europe.

One reason leadership in any one developed market increasingly requires leadership in all is that the developed world has become one in terms of technology.

All developed countries are equally capable of doing everything, doing it equally well and doing it equally fast.

All developed countries also share instant information.

Companies can therefore compete just about everywhere the moment economic conditions give them a substantial price advantage.

In an age of sharp and violent currency fluctuation, this means a leader must be able to innovate, to produce and to market in every area of the developed world or else be defenseless against competition should foreign-exchange rates sharply shift.

What triggered the present transnational rush was the overvalued dollar of the early ‘80s.

It demonstrated that currency fluctuations can be life-threatening even to the strongest business.

But it also showed that there is an effective defense: a transnational leadership position across the faultlines of currency earthquakes.

U.S. exports dropped like a stone in the years of the overvalued dollar and imports soared: not one major American industry could maintain its exports in the face of a currency fluctuation of almost 50 percent.

Yet only in steel, automobiles, consumer electronics, machine tools, and a few semiconductor lines did the world share of American products go down at all.

Overall, the world-market share of manufactured goods produced by U.S. -based companies stayed at the 20 percent to 22 percent level it has held since the ‘6os.

But this actually masks a substantial increase in the standing of American-based goods in the developed economies, since the slump in raw-material prices during the same period almost knocked out purchases by some of the U.S. ’s best customers, the developing countries of Latin America.

By contrast, American manufacturers with Western European ventures substantially increased their market penetration in computers and computer software, in pharmaceuticals, specialty chemicals, telecommunications equipment, and financial services.

In Japan a good many U.S. companies bought out their joint-venture partners.

This remarkable, unprecedented performance may explain in large measure why the overvalued dollar, despite its disastrous impact on American exports and the American balance of trade, did not push the U.S. into depression.

And because the world-market share of products made by U.S. based companies remained steady, the American businesses with foreign affiliates and units also maintained earnings and cash flow and could thus maintain research, product development and their capacity to innovate and to grow.

For while the overvalued dollar made American exports noncompetitive, it was a boon for the foreign affiliates and units of American companies.

Their parent companies’ dollars bought, during that period, almost o percent more—in new plants and machinery, in research, in product development, in marketing, promotion, and service, and in cash flow and earnings.

The prices the Americans paid for the buyouts gave their former Japanese partners a handsome profit in yen, but in dollars they were a bargain for the Americans.

These benefits required, however, a transnational base.

They did not accrue to the American machine-tool industry, for instance.

Ten years ago it had world leadership.

But it operated almost entirely in, and out of, the U.S. Hence the overvalued dollar sapped the industry’s ability to export and made it defenseless against imports, depriving it of the cash flow and the profits to maintain research and to develop new products.

Ford vs. GM

The automobile industry offers a similar lesson.

No company was hit harder in the early ‘80s by the tide of Japanese imports into the U.S. than Ford.

What saved it was its leadership position in the European market.

It gave Ford the profits and the cash flow that pulled it through the dismal years.

And because the dollar bought so much in Europe in those years, Ford could develop there the new models for the American market that now have made Ford highly profitable again in the U.S. and a serious contender for the domestic leadership it held 60 years ago.

GM, though twice Ford’s size, is essentially a one-country company—and is still floundering.

A transnational strategy is probably not compatible with diversification.

Instead, it requires a concentration of efforts.

An example is GE’s recent move to divest itself of its large consumer-electronics businesses in which it could not hope to rain worldwide leadership, in exchange for a substantial position in the European market for medical electronics, an area which GE has a reasonable chance to be a world leader.

Transnational strategy, in other words, is not an easy strategy.

But except for believers in miracles—and that is unfortunately what a belief in an early return to stable exchange rates amounts to—going transnational may be the only rational strategy for any business aiming at a leadership position anywhere in the developed world, whether in a mass market or in a market niche.

[1987]

What Really Ails the US. Auto Industry

General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler have improved car quality so much that several of their models are now as well made as anything the Japanese offer.

And through their discounts and financing deals they now offer the lowest prices.

Yet they still steadily lose market share to the Japanese.

Detroit has also sharply reduced costs; some new Ford plants in the U.S. and in Mexico may now be the world’s lowest-cost producers.

Yet the Big Three are losing money hand over fist while the leading Japanese companies are profitable.

All three—again with Ford in the lead—have sharply reduced the time it takes to develop a new design and bring it to market.

But in the meantime the Japanese have reduced their lead-times even further, so that the time gap between Detroit and the Japanese has hardly narrowed at all.

There are a great many different diagnoses of Detroit’s sickness: “fat” instead of “lean” manufacturing; union work rules: management’s short-term vision; departmental parochialism, and so on.

But the root of Detroit’s problems goes much deeper.

Detroit still operates on the assumption that the U.S. car market is homogeneous in its values and expectations but sharply segregated by income into four or five “socioeconomic” groups.

This theory of the market shapes how Detroit sees the market, how it organizes itself, and how it designs, makes, merchandises, and distributes its products.

But this theory became obsolete at least 15 years ago.

Sloan’s Legacy

Both the homogeneity of the market’s values and expectations and its socioeconomic segmentation were first discerned by Alfred P. Sloan right after World War I. Sloan built GM on this insight into the world’s biggest and for many decades its most profitable manufacturing enterprise.

And both Chrysler and Ford—Chrysler during its rise in the ‘20S and ‘30s, Ford during its rebirth after World War II—built themselves in GM’s image and on Sloan’s socioeconomic market segmentation.

The Sloan theory of the U.S. market worked for more than 40 years—a good deal longer than such theories usually last.

But it ceased to be valid in the ‘60s.

Ford’s Edsel should have been a roaring success.

It was researched, designed, and marketed as the ultimate socioeconomic car for the newly affluent “middle-middle” market.

Instead, it was rejected by every socioeconomic group.

The marketing success of that period was the Volkswagen Beetle—the symbol of the “youth culture” and a low-priced car for affluent people.

The 1973 petroleum crunch then finished off socioeconomic segmentation in the car market.

It made driving a small, fuel-efficient car fashionable, if not patriotic, and a status symbol for the upper-middle class.

Many older Americans, those over 55 or so, still buy cars according to socioeconomic segmentation.

But Detroit is losing the younger ones and with them the future.

Up to half of them buy “lifestyle” cars—primarily non-Detroit cars.

Income is, of course, still important.

But where it was the determinant in automobile buying from 1920 until 1965 or 1970, it has now become a restraint—in the U.S. , in Western Europe, and in Japan.

The determinant increasingly is “lifestyle”: that is, values and expectations a potential customer largely selects for himself.

And lifestyle is as elusive and qualitative a concept as socioeconomic segmentation was tangible and rigorously quantitative.

Equally important: Sloan’s theory of the market assumed one car per family.

But the American family today owns two as a rule.

There is nothing “typical” about the choice of the second car.

In the same upper-middle socioeconomic group—all two-career professional families—there may be the family whose two cars are a Buick and a Dodge minivan; the family with two compacts, one American, one Japanese; the family whose two cars are a big Mercedes and a Ford Escort; and the couple, both professors at the state university, who drive “His” and “Hers” BMWs.

Which of the four is “typical”?

A market of socioeconomic segments is stable.

It makes sense, then, to have long lead times for a new design.

A lifestyle market is fuzzy and extremely volatile.

One has to plan long-range and for every possible (or impossible) contingency so as to be able to act with extreme speed when opportunity knocks.

The lifestyle market is the one the Japanese take for granted, the market that they see, plan for, are prepared for.

For their automobile industry barely existed when socioeconomic market segmentation prevailed: it emerged only after World War II and entered the U.S. only in the ‘70s.

Japanese cars are therefore designed from the beginning as lifestyle cars, and the cars for one lifestyle market are designed to look very much alike regardless of price.

All Toyota “family cars,” for example, from the low-price Corolla to the luxury Lexus, have the same look of comfortable solidity.

They differ mainly in options and accessories rather than in style or in the way they handle.

But the Japanese are also organized to be opportunistic, which means that they continuously plan for every conceivable contingency so that they can move with lightning speed whenever an opportunity opens.

When the success of Honda’s Acura showed that there was a substantial market for a luxury car among baby boomers reaching middle age, Toyota and Nissan both already had detailed plans for such a car and this enabled them to have it produced and out in the market in less than three years.

The Japanese also try to design parts so that they can be combined in any number of ways even though this considerably increases the cost of tools and dies—rank heresy for any American automobile producer.

This made it possible, for instance, for Mazda to bring out in no time at all its sports car, the Miata—the marketing sensation of 1989.

Though it looks entirely different from any other Mazda car, 80 percent of its parts are standard.

This then enabled Mazda to make good money on the Miata even though it probably has sold fewer than a hundred thousand units, at which volume any American manufacturer would lose his shirt.

Detroit knows how to design successful lifestyle cars.

In fact, every truly successful American car since World War II been a lifestyle car: the Jeep as it was transformed after World War II from army roughneck into a high-performance and comfortable “outdoors” vehicle; the Rambler, American Motors’ original compact, which was designed as the second of the newly affluent; Ford’s Mustang and Thunderbird; Dodge minivan.

But despite these successes Detroit remains in the grip of Sloan’s socioeconomic market segmentation.

GM set up the Saturn Division a few years back as a new and separate lifestyle-based business.

But when the Saturn car was unveiled last year, it turned out to be just another socioeconomic car for the already overcrowded “middle-middle” segment.

Forty-five years of unbroken success are indeed hard to slough off.

Everybody in Detroit management has grown up with socioeconomic market segmentation as an article of faith, if not as a law of nature.

Worse: the way the Big Three are structured all but forces them into a socioeconomic straitjacket.

Sloan decentralized GM in the early ‘20S into divisions, each of which serves one socioeconomic segment.

He similarly organized distribution in dealerships, each serving one of these segments.

Despite countless reorganizations, this is still how GM, Ford, and Chrysler function.

As a result, planning, design and marketing are either socioeconomically determined—that is, run counter to the way the market now actually works—or, if one of the Big Three designs a lifestyle car it is then subordinated to the socioeconomic axiom.

One example: the Chevrolet Cavalier is arguably the best second car on the American market—small enough to park easily and big enough for the entire family and a lot of luggage.

But in order to give each GM division a “popular” car, it was parceled out among them.

Several divisions thus offer and advertise the same car under different names, through different dealers, and at different prices.

Thus GM customers are confused and complain that GM cars have lost all product differentiation.

GM customers also tend to settle for the cheapest version with the fewest options and accessories and thus with the lowest profit margin for GM.

The Cavalier’s main competitor, Toyota’s Corolla, is marketed, advertised, and sold as one model by one group of dealers and with a full array of options and accessories.

As a result, Corolla customers tend to buy the biggest package of options and accessories, which is where the profits are.

And the Toyota dealers can also give much better service because they have so much more volume.

Teams vs. Traitors

The socioeconomic bent of the American automobile industry also explains in large measure its long lead times in developing new models and in reacting to market changes.

Instead of being divided into autonomous market-segment divisions, the Japanese companies are decentralized into powerful, autonomous companywide functions, such as engineering, manufacturing, and marketing.

It is easy for them to form companywide teams to work on designs outside the existing product scope.

In Detroit, however, where market-segment divisions dominate, people who work on such teams risk being considered traitors by the division on whose payroll they are.

How can Detroit free itself from the straitjacket of its past success?

It may require the complete restructuring of the traditional divisions and of the traditional dealer system as well.

It may even require that GM, the biggest (and for more than 50 years, the most successful) company, be split into two or more competing businesses (which, incidentally, was advocated by some GM executives right after World War II).

And until Detroit restructures itself to fit today’s rather than yesterday’s American automobile market, and today’s American society, no amount of improvement in manufacturing processes, equality management, or interfunctional and interdepartmental teamwork is likely to restore it to health and to leadership.

[1991]

24. The New Japanese Business Strategies

Quietly and with a minimum of discussion, the leading Japanese companies are moving to new business strategies.

They are embracing a radically new—indeed, a heretical—theory: doing blue-collar manufacturing work in Japan is gross misallocation of resources and weakens both the company and the national economy.

They are also embracing an equally new—and equally radical—theory: leadership throughout the developed world no longer rests on financial control or on traditional cost advantages.

It rests on control of brainpower.

These companies are also quickly restructuring their organization on the assumption that the winner in a competitive world economy is going to be the firm that most effectively shortens the product life of its own products—that is, the firm that best organizes the systematic abandonment of its own products.

And they are moving away from Deming and Total Quality Management and toward Zero-Defects Management based on drastically different principles and methods.

The Japanese now hold about 30 percent of the American automobile market and expect to increase this share substantially in the next few years.

Yet they also expect to stop exporting Japanese-made cars to the American market altogether within the next three to five years; by 1995 or so Japanese marques sold in the U.S. should mostly be manufactured in plants located in North America.

Similarly, the Japanese expect to have something like one third of the automobile market of the European Economic Community by the year 2000 (whatever their present promises to the EEC to the contrary), but again without exporting many cars from Japan to Europe.

And Japanese multinationals—Toyota, Honda, Sony, Matshushita, Fujitsu, the ceramics leader Kyocera, the Mitsubishi companies, are all pouring staggering amounts of money into manufacturing plants in developing countries, in Tijuana on the U.S.-Mexican border, in all of South America, in Southern Europe, e. g., Spain, Portugal, and Turkey, and in Southeast Asia: Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand.

The standard explanations for moving manufacturing out of Japan are “foreign protectionism” and “Japan’s growing labor shortage.”

Both are legitimate.

The supply of young people available in Japan for blue-collar manufacturing work will, for instance, shrink by 50 percent in the next ten years—the combined result of the sharp drop in birth rates in the ‘70s and of the simultaneous educational upgrading to the point that virtually every Japanese boy now finishes high school and goes to college or into a white-collar job.

But both explanations are also smoke screens.

The real reason is the growing conviction among Japan’s business leaders (and also among influential bureaucrats) that manufacturing work does not belong in a developed country like Japan and is, indeed, a misallocation of such a country’s most expensive resource.

“Before youngsters can go to work on the assembly line,” my Japanese friends say again and again, “a developed country pours $100,000 in school expenses into them, whether they learn anything or not.

And then they have to get a middle-class income, lifetime security, a pension, and health care.

In Indonesia or in Tijuana they have never been to school and require no capital investment in their education; and they are ‘middle-class’ if we pay them one tenth of what they cost in the U.S. or in Japan.

Yet their productivity after two or three years of training is as high in Tijuana or in Bangkok as it is in Nagoya or Detroit.

When you figure the enormous social capital invested in them, the return blue-collar workers make to society in developed countries is at most one or two percent; in Latin America or Indonesia it’s twenty times that.”

Whenever I then argue that a country is highly vulnerable without a strong manufacturing base, I get the answer: “The supply of young people in the developing world, in South America, in Southern Europe, in Southeast Asia, will be so large in the next thirty years that it’s absurd to worry about the “manufacturing base” the way you in the U.S. do.

Indeed, it’s our social responsibility to Japan to make sure that as few as possible of our high-investment and high-cost young people are being misused for low-yield manufacturing work.”

But while manufacturing at home is now increasingly considered in Japan a liability and a drag on the performance of both manufacturing companies and national economy, the new Japanese strategies call for total control of what now matters: brainpower and knowledge.

To be competitive the world over, the argument goes, requires leadership in all important knowledge areas: technology, marketing, management, and firm control of what my Japanese friends are beginning to call “brain capital.”

“You Americans,” I am told over and over again, “thirty years ago virtually gave away to us your technology and your management know-how to gain through a joint venture access to the Japanese market.

We shan’t repeat that mistake.”

The Japanese are willing to pay very large sums of money to gain access to knowledge: through a minority participation in a Silicon-Valley computer specialist; through similar investments in U.S. and European pharmaceutical or genetics entrepreneurs; above all through financing research in Western (primarily U.S. ) universities.

The direct financial return on these investments is usually zero.

But what the Japanese are paying for is not dividends but access to the knowledge their partners will produce, and control over it—or at least priority in using it.

Increasingly Japanese companies employ foreigners in their international operations, both as professionals and as executives.

The large Japanese automobile manufacturers now all have design studios in Southern California, and they have Westerners running their international marketing.

But the use they made of the knowledge these foreigners produce—that is, its application to the company’s strategy and decisions—is considered “proprietary”—it is tightly held within the Japanese management team.

Whereas in the past some Japanese companies granted licenses of their knowledge to a Western company—e. g., on some Japanese-developed cardiac drugs—they are now revoking them or not renewing them.

Every major Japanese industrial group now has its own research institute.

Its main function is not technical research but “research into knowledge”—that is, to bring to the group awareness of any important new knowledge: in technology, management and organization, marketing, finance, training, developed anyplace in the world. (See “Concept Design” and “Concept R&D” here)

On my last trip to Japan a few months ago, I spoke at the twentieth anniversary of one of these “think tanks,” the research institute of the Mitsubishi Group.

At the lunch after my talk, one of the most respected elders of the Mitsubishi clan leaned over and said to me, “In another twenty years the entire Mitsubishi Group will be organized around this research institute, where we have always been organized around the Mitsubishi Bank or the Mitsubishi Trading Company.”

Everybody now knows that the Japanese can bring out a new product—e. g., a new automobile model—in half the time it takes their American competitors and in one third it takes the Europeans.

Everybody also knows that major U.S. companies have been rushing to emulate the Japanese and are reorganizing their research and development work on the Japanese model, that is, along cross-functional lines.

But the Japanese are already moving to the next stage.

They are reorganizing research and development so that it simultaneously produces three new products with the effort traditionally needed to produce one.

They do this by systematically starting out with a deadline for abandoning today’s new product set on the very day on which this product is first sold.

“The faster we can abandon today’s new product, the stronger and the more profitable we’ll be” is the new motto.

To most Western businessmen this is madness.

They believe that a product becomes more profitable the longer its product life.

For then the monies spent on developing it have been written off.

But “writing off” to the Japanese is accounting fiction—useful to cut taxes but otherwise sheer self-delusion.

Money spent on developing a product or a process is not “investment” to them; it is “sunk cost” (the economist’s term).

And they tend to accept what the great AustroAmerican economist Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950) preached: there is no “profit” except the short-lived innovator’s profit.

As soon as that’s gone—that is, as soon as there is competition in the marketplace for the new product—products don’t earn; they cost.

But the fundamental reason why the leading Japanese businesses are now shifting to organized abandonment as their strategy is not economic theory.

It is their growing conviction that the only alternative to themselves shortening the life cycle of the product is for a competitor to do so—and then the competitor will not only have the profits but the market as well.

“Of course,” my Japanese friends say, “some Western companies, e. g., 3M, have long operated on the policy that seventy percent of their sales five years hence will have to come from products that do not yet exist today.

But these companies rely on spontaneous upswelling of entrepreneurship from within.

We organize the company—and the key is systematic abandonment.”

By deciding in advance that they will abandon a new product within a given period of time, the Japanese force themselves to go to work immediately on replacing it, and to do so on three parallel tracks.

One track—the Japanese call it kaizen—is organized work on improvement with specific goals and deadlines—e. g., a 10 percent reduction in cost within 15 months and/or a 10 percent improvement in reliability within the same time, and/or a 15 percent increase in performance characteristics—and enough, in any event, that the improved product is substantially different, is in fact a new product.

The second track is “leaping,” that is, developing a new and different product out of the old—the best example is still the earliest one: Sony’s development of the Walkman out of the newly developed portable tape recorder.

And, finally, there is genuine innovation.

Increasingly the leading Japanese companies organize themselves so that all three tracks are pursued simultaneously and under the direction of the same cross-functional team.

The results—at least that’s the idea—is to produce not one but three new and different products to replace each present product and to gain, with the same investment of time and money, an improved product; a “leap”; and a genuine innovation, with one of the three then becoming the new market leader and producing the “innovator’s profit.”

Finally, the leading Japanese companies are moving from Total Quality Management (TQM) to Zero Defects Management.

The Deming Prize is still Japan’s ultimate business accolade and Dr. Deming is still a folk hero.

But what the leading companies increasingly practice was expressed in a recent statement by one of the top manufacturing people at Toyota.

“We can’t use TQM,” he said.

“At its very best—and no one has reached that yet—it cuts defects to ten percent.

But we turn out four million cars; and a ten-percent defect rate means that 400,000 Toyota buyers get a 100 percent defective car.

But Zero Defects Management is now possible and actually not too difficult.”

What the Japanese now practice is very much a return to Frederic Taylor’s “scientific management.”

Only the operators themselves, rather than the industrial engineer, take the initiative in studying the task, the work, and the tools, and instead of stop watch and photo camera, the operators use computer simulation.

What triggered this shift, paradoxically enough, was an American import: the big and highly successful Disneyland that opened outside Tokyo a few years ago.

“We all knew that it would take Disney three years to work the bugs out of this huge undertaking,” a leading Japanese industrialist told me; “instead it ran with zero defects the day it opened.

Every single operation had been engineered all the way through and simulated on the computer and trained for, and it suddenly dawned on us that we could do this too.

You know,” he continued, “the Americans are now all rushing to install TQM; that’ll take ten years before it really works—at least that’s what it took here.

This means it will work in America around 1995.

By that time we’ll have Zero Defects Management and will again be fifteen years ahead of you.”

These new Japanese strategies may not work.

Or they may turn out to work only for the Japanese.

But even if they are the wrong responses, they are at least responses to reality: the emergence of the highly competitive and worldwide knowledge economy.

[1991]

Chapter 25. Manage by Walking Around — Outside!

Everyone knows how fast technology is changing.

Everyone knows about markets becoming global and about shifts in the work force and in demographics.

But few people pay attention to changing distributive channels.

Yet, how goods and services get to customers and where customers buy are changing fully as fast as technology, markets, and demography.

And they are changing fast all over the world.

The bulk of consumer electronics—radios, TVs, VCRs, calculators—were sold in Britain 15 years ago by thousands of independent, locally owned “mom-and-pop” shops.

Today the bulk of these goods is sold by four national chains.

The mom-and-pop shop had to carry major manufacturers’ brands and relied on the manufacturers’ advertising.

The four big chains carry their own private brands and do their own advertising.

In the U.S. office furniture—chairs, desks, filing cabinets—was bought 15 years ago in specialized office-furniture stores.

Increasingly these goods are now being bought in discount stores and “buying clubs.”

The recent Japanese promise to repeal the law that protects their mom-and-pop shops and keeps out big stores and chains, has been hailed as a great American victory.

But in Japan’s metropolitan areas (where 60 percent of the population live and shop), a majority of the mom-and-pop shops have already been converted into franchises of huge chains such as 7-Eleven or Mister Donut.

Six or seven years ago, mutual funds were distributed in the U.S. through two channels: indirectly, through brokerage houses, and directly, through TV advertising.

These two channels still carry something like three-fifths of all mutual funds sold.

But one of the big mutual-fund groups (which six years ago sold exclusively through brokers) now sells 15 percent of products through regional banks, 15 percent through insurance agencies and another 15 percent through professional and trade associations.

Independent Outsiders

The hospital became a major market only 25 years ago.

But the hospital itself bought the goods it used.

Now a steadily growing share is bought by independent outsiders to whom the hospital contracts maintenance, patient feeding, billing, physical therapy, the pharmacy, X-ray, the medical lab, and so on.

Increasingly even large users do not themselves buy their computers.

They are bought instead by computer management firms that design, buy, install, and run their clients’ information systems.

A major computer maker, Digital Equipment Corp., now has its own computer-management subsidiary.

Where customers buy is changing fast too.

Many major department store chains are in serious trouble.

Some once great stores—Bonwit Teller, for instance, or B. Altman, only recently New York’s fashion leaders—are out of business.

Others, such as Bloomingdale’s, are in bankruptcy.

But one chain, Seattle-based Nordstrom, has been doing well.

The department stores that are in trouble are all organized and run as downtown stores with suburban branches.

Nordstrom has only suburban stores.

We may be seeing the first result of the slow but steady move of office work out of downtown and into the suburbs where the office workers live.

The big “wire houses,” the New York-based stockbrokers such as Merrill Lynch and Shearson Lehman, did exceptionally well only a few years ago.

Now they are losing sales and profits.

But some large “regional” houses (i. e., brokers not headquartered in New York), such as A. G. Edwards in St. Louis, are doing fine.

And so are some “institutional brokers” such as New York-based Sanford Bernstein.

The wire houses serve both the “retail customer”—the individual investor—and the “wholesale customer”—the pension funds.

A. G. Edwards serves primarily the retail market, Sanford Bernstein exclusively the institutional market.

Traditionally, large stockbrokers were successful in serving both markets.

But in no other line of business do retail customers and wholesale customers shop in the same place.

Are the securities markets now segmenting themselves the way every other market has?

Changes in distributive channels may not matter much to GNP and macroeconomics.

But they should be a major concern of every business and every industry.

Yet they are very difficult to predict.

What’s worse: they do not show up in reports and statistics until they have gone very far.

They are what statisticians call “changes at the margin.”

And by the time such changes become statistically significant, it is usually too late to adapt to them, let alone to exploit them as opportunities.

The one way to be abreast of them is to go out and look for these changes.

Here again are a few examples:

Alfred P. Sloan built General Motors into the world’s premier manufacturing company, in the ‘20s and ‘30s, by actually working with customers.

Once every three months he would disappear from Detroit without telling anyone where he was going.

The next morning he would show up at a dealer’s lot in Memphis or Albany, would introduce himself, and would ask the dealer’s permission to work as a salesman for a couple of days or as an assistant service manager.

During that week he would work like this in two more dealerships in two other cities.

The following Monday he’d be back in Detroit, firing off memoranda on changing customer behavior and changing customer preferences on dealer service and on company service to the dealer, on market trends and style trends.

GM in those years had the most up-to-date and comprehensive customer research in American industry.

And yet—at least so I was told by the then head of customer research at GM—Sloan, by actually working in the field, spotted more and more important trends than did customer research, and spotted them earlier.

Attention

The late Karl Bays made American Hospital Corp. the leader in its industry during the 1970s.

He himself credited his success largely to his going out into the field.

Twice a year he would take for two weeks each the place of a salesman on vacation.

When the salesman came back, Bays said (with a twinkle in his eye) “the customer always complained about the incompetence of his replacement and about the dumb questions I asked.”

But selling, Bays said, was not the point of the exercise; learning was.

Another variant: two men who together took over a small and lackluster chain of fashion shops in the mid-‘50s built it into one of America’s retail giants.

For 30 years, until their retirement, each spent every Saturday in a different shopping mall.

They did not visit their own stores.

They spent the day in other companies’ stores—some fashion stores, some bookshops, some stores for household goods and so on, watching shoppers, watching sales people, chatting with store managers.

And they insisted that every one of their senior executives do likewise, including the lawyer, the controller, and the vice president for personnel.

As a result, the company foresaw in the early ‘60s the coming of the “youth culture” and built or remodeled stores to attract teen-agers.

A few years later, when everyone talked of the “greening of America,” the company realized that the youth culture was passé and changed merchandise and stores to attract the young adult.

And another 10 years later, well before 1980, the company saw and understood the emergence of the two-earner family.

Dumb Questions

To be able to anticipate changes in distributive channels and in where customers buy (and how, which is equally important) one has to be in the marketplace, has to watch customers, and noncustomers, has to ask “dumb questions.”

It is almost 40 years since I first advised executives to “walk around”—that is, to get out of their offices, visit and talk to their associates in the company.

This was the right advice then; now it is the wrong thing to do, and a waste of the executive’s scarcest resource, his time.

For now we know how to build upward information into the organization.

To depend on walking around actually may lull executives into a false sense of security; it may make them believe that they have information when all they have is what their subordinates wanted them to hear.

The right advice to executives now is to walk outside.

36. Sell the Mailroom. Unbundling in the ‘90s

More and more people working in and for organizations will actually be on the payroll of an independent outside contractor.

Businesses, hospitals, schools, governments, labor unions—all kinds of organizations, large and small—are increasingly “unbundling” clerical, maintenance, and support work.

Of course, the trend is not altogether new.

A great many American hospitals—and European and Japanese hospitals as well—now farm out maintenance and patient feeding; 40 years ago none did.

“Temporary help” firms go back more than 30 years; but while in the beginning they handled file clerks and typists, they now provide computer programmers, accountants, engineers, nurses, and even plant managers.

Cities farm out “waste management” (once known as street cleaning and garbage disposal); even prisons are being run by private contractors.

Farm Out Clerical Work

The trend is accelerating sharply in all developed countries.

In another 10 or 15 years it may well be the rule, especially in large organizations, to farm out all activities that do not offer the people working in them opportunities for advancement into senior management.

This may indeed be the only way to attain productivity in clerical, maintenance, and support work.

And increased productivity in such work will increasingly become a central challenge in developed countries, where such work now employs as many people as manufacturing does.

Support work is rapidly becoming capital-intensive.

In many manufacturing companies, the investment in information technology for each office employee now equals the investment in machinery for each production worker.

Yet the productivity of clerical, maintenance, and support work is dismally low, and is improving only at snail’s pace, if at all.

Unbundling will not by itself make this work more productive.

But without it the productivity of clerical, maintenance, and support work is unlikely to be tackled seriously.

In-house service and support activities are de facto monopolies.

They have little incentive to improve their productivity.

There is, after all, no competition.

In fact, they have considerable disincentive to improve their productivity.

In the typical organization, business, or government, the standard and prestige of an activity is judged by its size and budget—particularly in the case of activities that, like clerical, maintenance, and support work, do not make a direct and measurable contribution to the bottom line.

To improve the productivity of such an activity is thus hardly the way to advancement and success.

When in-house support staff are criticized for doing a poor job, their managers are likely to respond by hiring more people.

An outside contractor knows that he will be tossed out and replaced by a better-performing competitor unless he improves quality and cuts costs.

The people running in-house support services are also unlikely to do the hard, innovative, and often costly work that is required to make service work productive.

Systematic innovation in service work is as desperately needed as it was in machine work in the 50 years between Frederick Winslow Taylor in the 187os and Henry Ford in the 1920s.

Each task, each job, has to be analyzed and then reconfigured.

Practically every tool has to be redesigned.

When Ray Kroc, the founder of McDonald’s set out to make hamburger shops more productive, he redesigned every single implement, including spoons, napkin holders, and skillets.

To improve productivity, hospital-maintenance companies have had to redesign brooms, dustpans, wastepaper baskets, and even sheets and blankets.

In building Federal Express, Fred Smith studied every single step in the collecting, transporting, and delivering of packages, and in billing for the work.

And then people have to be trained and trained and trained.

This requires single-minded, almost obsessive dedication to one narrow objective—making hamburgers, making hospital beds, delivering packages—to the exclusion of everything else.

But such singleminded dedication is far more characteristic of an independent outside entrepreneur than of a department head within an organization who is expected to be a team player.

The most important reason for unbundling the organization, however, is one that economists and engineers are likely to dismiss as “intangible”: the productivity of support work is not likely to go up until it is possible to be promoted into senior management for doing a good job at it.

And that will happen in support work only when such work is done by separate, free-standing enterprises.

Until then, ambitious and able people will not go into support work; and if they find themselves in it, will soon get out of it.

It is hardly coincidental that the productivity decline in American factories set in as soon as finance and marketing were taking over from manufacturing in the early ‘60s as the main avenues of advancement into senior management.

Nor is it coincidence that stockbrokers have been plagued by recurrent “back office” crises despite steadily increasing employment and increasing investment in clerical and support work.

Until very recently even the head of the back office (though responsible for half the firm’s expenses) was at best a “titular” partner.