Age of Discontinuity — 1968

by Peter Drucker — his other books

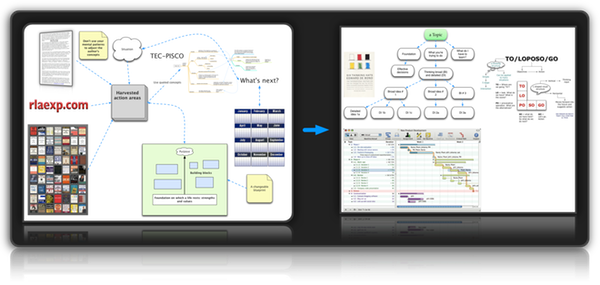

See rlaexp.com initial bread-crumb trail — toward the

end of this page — for a site “overview”

Amazon Link: The Age of Discontinuity: Guidelines to Our Changing Society

Contents ↓

Preface To The Paperback Edition (1978) Preface To The Paperback Edition (1978)

Preface Preface

- Knowledge Technologies

- End of Continuity

- New industries

- Aging "modern industries"

- Industries on the horizon

- New knowledge base

- New entrepreneurs

- Dynamic of technology

- Dynamic of markets

- Innovative organization

- New economic policies

- Tax laws & craft unions

- Hidden protection/open subsidy

- Cues from growing edges of the world economy

- New vs. decay

- World economy

- Global Shopping Center

- Mass consumption / common demand

- Global Money & Credit

- An Institution to represent the world economy

- Making the poor productive

- World divided into those who know how & those who don't

- Need a theory of economic development

- Beyond the new economics

- Inability to manage the economy

- What we need:

- Society of organizations

- New pluralism

- Toward a Theory of Organizations

- Making organization perform

- Organization & The Quality of Life

- The legitimacy of organizations

- Sickness of Government

- Farm out the doing to business & private institutions

- Abandonment

- How can the individual survive?

- Every organization, no matter what its legal position or ownership—a special purpose tool

- Internal powers of the organization

- Individual freedom: the right to emigrate.

- Individual opportunity in organization.

- Knowledge society

- Knowledge Economy (production, distribution, procuring ideas & info)

- Central factor of production

- Importance to international (transnational) economy

- Learned to learn

- Know opportunity in large organizations

- Increased working life span

- Delayed entry

- Ratio: productive & dependent members

- Demand for education

- Work & worker in the Knowledge Society

- Teams, MBO, task rule

- Second careers for knowledge workers below top rank

- Problems of transitions for

- Has Success spoiled the schools?

- What is school for?

- Public concern

- Learned to learn

- Continuing edcation: best time to learn

- Impacts of long years of school

- New learning & teaching

- Right tools & methods

- Teaching & learning

- Politics of knowledge

- Organize Knowledge & search for it around areas of application rather than subject

- Equal opportunity for education

- High cost = government. Support.

- Does knowledge have a future? (Morality)

- How people of knowledge accepts & discharge their responsibility

- See Population Changes

Preface to the Paperback Edition (1978)

When this book was first published (1968), almost a decade ago, such major shocks as the petroleum cartel of 1973 or Watergate were still well in the future, still unpredictable, indeed inconceivable.

The environmental crusade had barely begun.

But even if I had been able to foresee these momentous events, I would not have paid much attention to them in this book—just as I paid scant attention to the headlines of the late sixties, such as the Vietnam War or the student unrest.

For this book tries to do something that is altogether different and perhaps more ambitious than forecasting.

It does not try to predict “developments,” no matter how important.

It attempts, instead, to identify and to define changes that are occurring or have already occurred in the foundations.

Its themes are the continental drifts that form new continents, rather than the wars that form new national boundaries.

“Discontinuity” is what I called these major changes in the underlying social and cultural reality.

This was a rather novel term at the time—although [perhaps as a result of this book and its success] it has become a good deal more familiar since.

“Revolution” was, and still is, a term in wide use; indeed it may be greatly overused.

But what is a discontinuity?

The term, as the geologist uses it, denotes much more and much less than does revolution.

Revolution is the earthquake or the volcanic eruption that obliterates the familiar landscape and creates a new one.

But these revolutions are largely the effects of shifts in the foundations that precede them and make the revolutions inevitable.

These revolutions result from discontinuities: from the buildup of tension between a new underlying reality and the surface of established institution and customary behavior that still conform to yesterday’s underlying realities.

And while revolutions tend to be violent and spectacular, discontinuities tend to develop gradually and quietly and are rarely perceived until they have resulted in the volcanic eruption or the earthquake.

Revolutions

Landmarks of Tomorrow

Post-Capitalist Society

Moving Beyond Capitalism?

Let me illustrate with something from the history of the book itself.

Chapter 10, “The Sickness of Government” was published in a magazine a few months before the book itself appeared, and just when Richard Nixon was sworn in for his first presidential term.

Mr. Nixon took occasion, in one of his first public speeches as president, sharply to attack the book.

“Peter Drucker,” he said, addressing the employees of the Department of Health, Education and ‘Welfare (HEW), shortly after his inauguration in early 1969, “says that modern government can only do two things well: wage war and inflate the currency.

It is the aim of my administration to prove Mr. Drucker wrong.”

In one way, Mr. Nixon did indeed prove me wrong—though hardly in the way in which he meant it.

His administration showed in Vietnam that modern government may perhaps not even know how to wage war—though it also showed that it knew only too well how to inflate the currency.

But in the sense in which Mr. Nixon meant his attack on the book to be understood, his administration amply proved the thesis of this book.

For the earthquake, the volcanic eruption of Watergate, very largely resulted from the fundamental discontinuity between the sickness of Government, which this book identifies and discusses, and Mr. Nixon’s attempts to defy this reality through his “Imperial Presidency.”

Since this book first appeared, its fundamental thesis—that the post-World War II period was the end rather than the beginning of an age—has become widely accepted.

But little attention is being paid to the major shifts themselves.

Most observers still look backward—this book tries to look forward.

That such shifts have occurred, irreversibly, may be seen, or perhaps only be felt.

The slogans, however, whether of the Right or of the Left, of the Free World or of the countries of totalitarian Communism, whether of developed or of developing countries, are still those of yesterday’s realities and so, I fear, are most of the policies proposed.

Yet the past decade, since this book first appeared, has, I can say confidently, borne out my basic analysis.

This book identifies a discontinuity in four areas:

in the rapid emergence of new technologies and of new industries based on them; in the rapid emergence of new technologies and of new industries based on them;

in the emergence of a genuine world economy, in which the relations between developed and developing nations take the place of the class conflicts within a national economy that dominated the nineteenth century (and still dominate rhetoric and policy as a whole). in the emergence of a genuine world economy, in which the relations between developed and developing nations take the place of the class conflicts within a national economy that dominated the nineteenth century (and still dominate rhetoric and policy as a whole).

At the same time, the world economy is seen in this book as having become both the dynamic and policy-setting center for all economies, and the area in which new economic and social institutions would evolve;

the emergence of a new pluralism of institutions that obsoletes traditional, and still generally accepted, theories of government and society, but that also severely endangers and perhaps destroys the ability of government to perform; the emergence of a new pluralism of institutions that obsoletes traditional, and still generally accepted, theories of government and society, but that also severely endangers and perhaps destroys the ability of government to perform;

finally, the emergence of knowledge as the new capital and as the central resource of an economy, and of the men of knowledge, that is the managers of institutions, as the new power center and leading group. finally, the emergence of knowledge as the new capital and as the central resource of an economy, and of the men of knowledge, that is the managers of institutions, as the new power center and leading group.

This implies, as this book argues, that the responsibility and accountability of knowledge and of men of knowledge would become a central issue for political theory and public policy and a central moral concern.

That Watergate was in large part a result of the discontinuity that I call “the sickness of government,” and especially of the refusal of the Nixon Administration to take this discontinuity seriously, has been said already.

But the oil crisis of 1973 was also largely a result of such a discontinuity: the shift from national to world economy as the true dynamic center.

Not only did the oil crisis show dramatically the total dependence of all countries and of all economies on the world economy, in sharp and irreconcilable contrast to the doctrine of the national economy which still passes for orthodoxy among economists.

The OPEC cartel could not have succeeded but for the “race war” sentiment of the developing world.

For the developed countries, the high price of petroleum is not much more than an inconvenience and a political embarrassment.

Financially and economically, it actually strengthens them.

For the added revenue of the petroleum exporting countries, both that part of it that comes from the developed countries and that part that comes from developing countries of the Third World, can be used in only two ways both benefiting directly the developed industrial countries.

It can be used to buy goods from the developed countries.

Or it can be invested in the developed countries.

For the developing countries, however, the petroleum cartel with its high price for energy and fertilizers poses a mortal threat.

Yet when the petroleum-producing countries quadrupled crude oil prices in 1973, all the developing countries cheered including even those that, like India, Brazil, or Pakistan, knew immediately how serious a threat the higher petroleum price posed to their own economies and their own economic and social stability.

Without support from the developing world, OPEC would have collapsed within a few months.

The developing countries, even when they knew how dangerous the high petroleum price was to their own economic future, saw OPEC's action as a blow against this “class enemy” in the world economy’ and as a first successful attack on the power and dominance of the rich and developed Western countries.

This may have been a mistake—cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face usually is.

But it also demonstrated that the developing countries tend to act in terms of a world economy, despite their intense and almost feverish nationalist rhetoric.

Similarly, the change in the world position of the multinational corporation in the last ten years can only be explained as a result of the discontinuity that the emergence of the world economy represents.

This book argues that the multinational is, or should be, of greatest importance and benefit to the developing countries, and that indeed it should be considered an absolute necessity by them.

For the developed countries and their governments, however, the book asserts, the multinational would pose increasingly serious political problems.

At the time at which it was written, this seemed to contradict completely what everybody knew.

The multinational was the villain in practically all developing countries; most of which, one way or another, seemed determined to get rid of it.

In the developed countries, on the other hand, the multinational was generally approved of, without too much criticism or debate.

Ten years later, that is now, these positions have become almost completely reversed.

In one developing country after another, the multinational is now seen as the one hope—or at least as a necessity.

Laws passed with great fanfare a decade ago to exclude, or at least to limit, the multinational—for instance the Andean Pact legislation of the countries on the west coast of South America, from Venezuela to Chile—have either been repealed or are being quietly shelved.

At the same time, it is the developed country, and especially the United States, where the multinational is now increasingly under the most serious attack.

But even within the developed countries, the positions in respect to the multinational are rapidly being reversed.

Ten years ago, John Kenneth Gaibraith, the Harvard liberal economist, was almost alone among leading economists in the developed world in his condemnation of the multinational.

But in the spring of 1977, Galbraith declared that the multinational had become the only economic hope and the most positive force for economic development and economic integration of the developing countries.

And finally, the tremendous surge in the demand for social responsibility and accountability of managers—in business, but also in hospitals and in government agencies—since this book was first published, testifies to both the effects of the discontinuity that I call the “new pluralism of organizations,” and the effects of the discontinuity that lies in the emergence of “knowledge” people as the new power center.

******

Bringing out a book in a new edition, a decade after it has been written, inevitably raises the question: Would the author still write the same book today?

Of course one never writes the same book a second time.

But on re-reading this book, I find that I would not take out very much of what I wrote then, in the late sixties.

I would modify this statement, change this or that illustration, perhaps shift the emphasis slightly here or there.

But, by and large, the book seems to me to have worn well.

The main trends I then saw are still the main trends today, only perhaps more so.

Some of the assertions that seemed least credible to readers of 1969, e.g., the assertion that modern government is indeed very sick, are by now home truths.

But if I were to write this book again today, I would probably add a new chapter, or at least sound one new note.

One major development is barely mentioned in this book.

It is perhaps not of the same fundamental character as the discontinuities with which the book deals.

But it is a major shift, nonetheless.

And it is bound to have great impact during the rest of this century on economy, on government, and also on the basic world view of modern man.

This is the shift in population structures and population dynamics and especially the fact that basic population dynamics are moving in different directions in the three major parts of our world: the developed countries of the industrial world, from Japan to the German border with the Soviet Bloc, the countries that include—in addition to Japan—North America and western and northern Europe; the developed countries of the Soviet Bloc, that is European Russia and her European satellites, East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Rumania; and finally the developing countries of the Third World.

In the developed industrial countries of the free world, we experienced a “baby boom” right after World War II.

It varied greatly in intensity and length.

But it was a universal event, though in Great Britain it was quite short-lived.

Everyplace, the number of babies born to a woman of child-bearing age went up sharply—families suddenly became much larger than they had been for a long time.

And then, in all these countries, there was a “baby bust": earliest perhaps in Japan—around 1955—but reaching the United States by 1960, with Western Europe in between.

The number of births per woman of child-bearing age fell drastically, as much as a quarter within a few years.

And at the same time, the number of older people began a sharp and steep rise, partly because many more people now reach retirement age than ever did before, and partly because those who live to 65 tend to live much longer afterwards than ever before.

* For the full implications of these developments, see a recent book of mine: The Unseen Revolution: How Pension Fund Socialism Came to America (New York: Harper & Row, 1976).

All three developments are unprecedented in human history.

There never was anything before resembling the baby boom.

In the United States, for instance, the number of babies born increased almost fifty percent within five years, between 1948 and 1953—is no such development on record in man’s earlier history.

But, there is also no precedent for the baby bust.

And the most fundamental development of them all, the sharp increase in the number of people who survive into old age, and even more the sharp increase of those who enjoy long years of old age, is equally without precedent.

But the twenty-five years between World War II and the early 1970's witnessed another important population development in the developed countries of the free world—quite unprecedented the sharp change in birth rate and life expectancies.

In all these countries there were very sharp migrations from in pre-industrial areas into the industrial world, and especially into the big cities.

In the United States, this was the migration of pre-industrial rural people, white and black, into the big cities, from New York to Atlanta, Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

In Europe, where the rural population had already moved into the city well before ‘World War II, and basically well before World War I, there was a tremendous movement of “guest workers” from the countries of the Mediterranean—Portugal, Spain, Yugoslavia, Greece, Turkey, Morocco, and Algeria—into the industrialized north, from northern Italy to Sweden, and particularly into Switzerland, Belgium, Germany, Holland, and even into xenophobic Great Britain.

In Japan, very large numbers of people streamed from the farms, especially in the backward and poor north, into the great industrial centers along the Tokyo-Osaka corridor.

But like the baby boom, this tremendous wave of migration was a short-lived phenomenon.

By the early seventies, that is, just about the time the baby bust set in in the developed countries in full force, the great migration was over.

In part, this is because the reservoirs had been exhausted.

There are no more reserves of underemployed people on the Japanese farms.

Where Japan in 1946, after World War II, had almost sixty percent of her population on the land, the figure is now down to eight percent, and most of them are women and elderly women at that.

In the United States, similarly, the exodus from the impoverished sharecropping shanty into the big city is over—the sharecropping shanty today stands empty, with the work being done by tractors instead.

And while there are still tremendous masses of underemployed or unemployed laborers in the Mediterranean countries, western and northern Europe are no longer capable of absorbing them.

Indeed, all these countries have passed the point at which they can easily absorb new pre-industrial migrants.

It is almost certain that the number of guest workers in western and northern Europe will go down rather than up from now on—socially and culturally they can no longer be accommodated.

In all these developed countries, the sixties and seventies were years in which very large numbers of young people reached adulthood and entered the labor force.

But by the early eighties this will be over.

From then on, we can expect for the rest of this century a sharp drop in the number of young people—and at the same time, such young people as are reaching adulthood will increasingly be people with long years of formal education and there fore available for “knowledge work” only.

In the traditional categories of work—manual labor, especially manual factory labor—we face at least a quarter century of great shortage.

At the same time, the number of older people is increasing rapidly—and very few people seem to realize how fast the shift is going on.

In 1935, when the United States first adopted nationwide Social Security, there were nine people in the American labor force for every American over 65.

Today, despite an unprecedented and almost explosive growth of the American labor force, the ratio is three Americans in the labor force for every American over 65.

And by 1985, the ratio will be two and a half to one.

One implication of this is that the support of the older people will increasingly become the first concern of developed economies.

To some extent, this can be assuaged by postponing retirement.

In the United States, we have already gone very far towards legislating later retirement, both for reasons of economics and because it will increasingly be felt as inhumane and cruel to deny older people, who are physically and mentally fit to work, access to work on grounds of age alone.

For a large and growing number of these people do not want to retire.

This is especially true of knowledge people who, by and large, fear retirement—whereas the manual worker, after a lifetime of rather dull and often physically demanding work, may welcome retirement.

But postponing retirement can only ease the situation.

It is no solution.

But such solutions as we have also mean a drastic shift in all developed countries.

It means, in effect, that the employees have come to be the owners of industry, through their pension funds.

This development is most clearly pronounced in the United States, where employee pension funds, those of business but also of public service institutions such as hospitals and universities and those of local governments, already owned one-third or more of the equity capital of America’s big and medium-sized companies in the mid-seventies and can be expected, by the mid-eighties, to have a solid majority of the share capital of American business in their pension portfolios.

In Europe, the same development is under way in a slightly different form, with one or a small number of central pension funds becoming increasingly the owners of industry under various laws already enacted or in the legislative hopper.

And in Japan, the same process is taking place, although there employee ownership is not the route.

Rather, it is “lifetime employment,” under which the enterprise is being run for the benefit of the employees, and increasingly for the benefit of retired employees as well.

These are fundamental structural changes with tremendous impact.

What makes them even more important is that developments in the rest of the world follow a very different pattern.

In the developed countries of Communism—that is, in European Russia and the European satellites—the age structure is the same as here.

People live longer.

And in these countries they retire even sooner.

The support of the older people in these countries will therefore become as much the central concern as it is bound to become in the developed societies of the West.

But the babies are missing.

There was no baby boom behind the Iron Curtain.

In European Russia, the years of World War II were years in which no children were born—and few of those that had been born in the years just before the German invasion survived those horrible times.

But the birthrate recovered only slightly.

It is well below the birthrate of the baby bust in the West, and has been at this very low level now for more than thirty years.

And while in most of the European satellites, except Poland, there was no major wartime destruction—so that the babies born during those years survived, by and large—the birthrate since has been low and is drifting lower still.

In all these countries, the birthrate is also, as in European Russia, well below the net reproduction rate—that is the rate needed to maintain the population level.

It is far below the level these countries need to satisfy simultaneously the demands of industrialization to which they are committed and the demands made by huge military forces, based on conscripts serving long years in their early manhood.

And while in European Russia there is still a very large farm population—one-third or more of the labor force—it cannot be drawn upon to make up the deficiencies and labor shortages that threaten both the economy and the manpower supply for the armed services.

For the labor shortage is hitting Russia just at the time when farm production is most needed and is indeed in severe crisis.

In the developing countries, finally, the basic problem will be to find jobs for enormous numbers of young adults.

For the babies of the fifties and sixties did not, as all earlier generations of babies in these countries did, die in their infancy.

Of every ten babies born in Mexico in 1938, for instance, only two or three were still alive in 1958.

The birthrate fell very sharply in Mexico after World War II, as it did in all developing countries—contrary to what most people seem to believe.

Indeed, the drop in the birthrate in the developing countries—except maybe in China, of which we have no direct and reliable information—has fallen more sharply since World War II than it did in any part of the world in any period of recorded history.

And yet the drop in infant mortality in these countries was much sharper still.

Of every ten babies born in Mexico in 1958, seven or eight are alive today and in reasonably good physical and mental state.

What is more, these young adults are not—as their parents were at the same age—tucked away in some remote mountain valley.

They are in the city.

They are visible.

They have political, economic, and social power and political, economic, and social significance.

And they need jobs.

At the same time, very few of these countries have enough of a domestic market to absorb more than a small fraction of this huge a labor supply, even if the capital were available.

Brazil may be one exception, with India another one, although only to a limited extent.

But the rest of the developing world does not have the domestic markets to absorb the goods and services these very large numbers of new workers could produce, even if they worked most inefficiently and were paid just enough to keep body and soul together.

The only hope for these countries is to find jobs in export production—and that means production for the markets of the developed countries, which alone have the purchasing power to absorb these goods.

But in the developed countries, the only labor available after the early eighties will be women past 35, available mainly for part-time work, and older people who keep on working beyond what is now considered standard retirement age.

Otherwise, the supply of people for manual work and for low-skilled clerical work will be barely enough to do the jobs that have to be done at home.

Cleaning the streets and collecting the garbage; carrying bedpans in the hospital and food to the patients in the hospital beds and a host of other manual chores have to be done at home and cannot possibly be farmed out abroad.

Manufacturing work that is highly labor-intensive will increasingly have to be moved where the labor supply is—that is to the developing countries.

In fact, the most significant economic development of the 1970's may well have been neither the petroleum crisis nor the recession.

It may have been the very rapid development of what I call “production sharing.”

In this process, for instance, the American manufacturer of “chips,” that is, electronic semiconductors, exports his products to Hong Kong or Singapore, where the chips are put into a steel case, typically made in India where there is a good deal of excess steel capacity; then a Japanese company puts its brand name on the finished hand-held calculator and sells it all over the world, with one-fifth to one-quarter of the output coming back to the United States, where it is then considered a “Japanese import.”

Or, to give another example, there is the large European textile company that spins, weaves, and dyes in Europe and then airfreights the cloth to Morocco, Nigeria, or Indonesia, where it is worked up into clothing, sheets, pillowslips, rugs, or upholstery fabric and airfreighted back to Europe to be sold in the Common Market.

That this production sharing goes counter to all traditional concepts of exporting or importing is obvious.

What, for instance, is the hand-held calculator—an “import” into the United States, or the form in which U.S.-made electronic semi-conductors go to the world market, that is, an “export"?

As yet, neither economic theory nor economic policy knows how to tackle this new development—and yet it may well become the most dominant development in the world economy in the next ten or twenty years.

Altogether the changes in population structure and population dynamics will create major new problems and major new opportunities.

Perhaps this change is not a major “discontinuity” of the same kind as the others discussed in this book.

After all, within twenty years or so the population structure may well stabilize again.

By that time, the population explosion in the developing world should be over.

Already the gap between birthrates and death rates is narrowing sharply in all these countries.

The death rate is no longer going down and the birthrate is still sliding sharply.

By 1990 or so, the two are likely to have reached a new balance—the same kind of balance, perhaps, that now characterizes the developed countries.

Indeed, in such countries as Taiwan or Korea this has already occurred—and it is not too far away in most countries of Latin America.

But for the next twenty years, population dynamics will be a major discontinuity.

At the same time, however, population dynamics will only serve to accentuate the other discontinuities discussed in this book.

They will quite obviously push the economic center of gravity even further toward a world economy, while at the same time aggravating the confrontation between the developed countries, eager as all of them are to protect their aging workers in old manufacturing industries, and the developing countries, in desperate need of manufacturing jobs that can only be provided by access to the markets of the developed countries.

Population dynamics will clearly make the multinational even more important, especially for the developing countries.

But it will also increase the institutional pluralism and the crisis of government in the developed countries and its impotence in controlling events within their own borders.

And it will make the knowledge worker even more important, since it is knowledge work that alone can make production sharing possible.

Indeed, production sharing is likely to call for a sharp increase in the number of managers, professional people, technicians, and so on, in the developed countries.

It makes very high demands on managerial ability and calls for the application of rather sophisticated knowledge—tools to the economic process.

Population dynamics, in other words, make the discontinuities of this is book more, rather than less, important.

But by themselves they are also an important development that surely would call for careful and thoughtful consideration, were I to write this book over again today.

******

When this book was first published it became an instant bestseller in two countries, the United States and Japan.

In the United States, it was on the bestseller list for a number of weeks.

In Japan it was the “national bestseller” for an entire year.

Indeed, the word its Japanese translators coined for “discontinuity,” for which no Japanese term existed at the time, has become a household word, to the point where Japanese fashion editors now talk of a “discontinuity” when the hemline goes up or down two inches.

In both countries the book has continued to enjoy wide readership and to exert considerable influence.

But to me, the most interesting development is what happened in Europe.

For in Europe the book was only moderately successful at first.

It was indeed translated almost immediately into most European languages.

But it was largely treated as an “American book"; of interest to those who want to know what goes on in the United States, but not particularly relevant to Europe.

This has changed dramatically in the last few years—not only in respect to the sales of the book, but even more in respect to its place in Europe’s public discussion and in the way in which the book is commented upon again and again in the popular press and in scholarly works and learned articles.

When I was asked to lecture in a number of European countries in the summer of 1977, my hosts in every country insisted, for instance, that I focus on the topics of this book, rather than on events in the headlines.

Does this mean anything?

Or is it just an anecdote?

I believe that this sharp shift in the attention that The Age of Discontinuity is receiving in Europe is a symptom of a fairly important development.

In the United States, the post-World War II period had already come to an end when this book appeared.

The decisive event, I am convinced, was President Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, rather than the Vietnam debacle, the student unrest, or the “petroleum shock” of 1973.

For me at least, President Kennedy’s assassination marked the end of an era.

It was the event that started the thinking that, a few years later, resulted in my writing this book.

And I believe that President Kennedy’s assassination similarly hit a great many people in this country in their subconscious.

It reminded all of us of the dark forces that lurk just beneath the thin veneer of civilization that we had thought to have repaired during and after World War II.

In Japan, too, President Kennedy’s assassination had a deep traumatic effect and made people aware that something irreversible had indeed occurred.

But in Europe, the years around 1970 were, so to speak, the Indian Summer of the post-World War II era.

In fact, Europe was in a state of euphoria in those years.

Only a few years earlier, Europe had been concerned about the “American threat.”

The bestselling book in Europe in the mid-sixties bore the title Le Défi Américain (The American Challenge).

Written by a French journalist, Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber, it asserted that Europe was about to become a colony of American big business, and that indeed the process had gone so far that it could not be undone.

And only a few years earlier, one of the most respected European economists, the Englishman Geoffrey Crowther, had stated flatly that for all foreseeable time to come the American dollar would be king in the international economy.

By the late sixties and early seventies, however, it had become crystal clear that these predictions were totally in error.

By that time, the “dollar shortage” had already turned into a “dollar glut,” and America was piling up one balance of payments deficit after another.

People in Europe muttered darkly about America becoming the “sick man” of the world economy.

And the European industry, which to Servan-Schreiber seemed to be hopelessly outmoded and overtaken by American entrepreneurship and American technology, had moved into the lead with European exports, symbolized for instance by Volkswagen’s Beetle, making serious inroads into the American market.

The German mark and the French franc were the “stars” in 1969 and 1970, rather than the American dollar.

Politically too, in those years, Europe felt it had the answer in the steady, continued and apparently permanent expansion in parallel of “welfare state” and “industrial economy”—for the inflation that has since proven the two to be incompatible beyond a point had not yet emerged as the major threat to economic growth and free institutions alike.

England, to be sure, was seriously weak even then.

But the sharp decline of English economic strength had not yet become apparent.

And it was widely believed that England’s entry into the European Common Market would provide a fast and complete cure for whatever ailed the English economy.

There were, of course, plenty of dissenting voices in Europe, as there were in the United States in those days.

But they were essentially the traditional nineteenth century voices of dissent, whether conservative, liberal, or Marxist.

A dissent couched, as was The Age of Discontinuity, in a very different mode was almost bound to fall on deaf ears in the Europe of 1969.

That The Age of Discontinuity is now rapidly becoming a widely read, widely discussed, and seriously considered book in Europe, may thus indicate a profound shift in Europe’s perception of the world and of her own place in it.

Above all, the Europe of 1969 was not ready to accept that modern government, that specific invention and central institution of modern Europe, was in profound crisis—the Europe of 1978 knows it.

There were plenty of books around in 1969 that predicted doom and gloom.

There are even more such today.

The Age of Discontinuity does not belong in this category.

It is not an optimistic book, to be sure.

But it does hold out some hope.

It identifies and discusses very serious problems.

But it sees them, above all, as great opportunities for fresh thinking, fresh policies, and for a great outburst of creative energy in political thought and political action, in educational thought and educational action, and in economic thought and economic action.

The Age of Discontinuity deals with opportunities for human work and human accomplishment.

I am, therefore, very pleased that this book of mine is being reissued now.

I only hope that it will reach many new readers, and especially many new young readers.

For it is the young, especially the educated young knowledge people, for whom the “age of discontinuity” should, above all, be an Age of Opportunity.

Peter F. Drucker

Claremont, California

New Year’s Day, 1978

Preface

In guerrilla country a handcar, light and expendable, rides ahead of the big, lumbering freight train to detonate whatever explosives might have been placed on the track.

This book is such a “handcar.”

For the future is, of course, always “guerrilla country” in which the unsuspected and apparently insignificant derail the massive and seemingly invincible trends of today.

Or, to change the metaphor, this book may be looked at as an “early-warning system,” reporting discontinuities which, while still below the visible horizon, are already changing structure and meaning of economy, polity, and society.

These discontinuities, rather than the massive momentum of the apparent trends, are likely to mold and shape our tomorrow, the closing decades of the twentieth century.

These discontinuities are, so to speak, our “recent future” both already accomplished fact and challenges to come.

Major discontinuities exist in four areas.

Genuinely new technologies are upon us.

They are almost certain to create new major industries and brand-new major businesses and to render obsolete at the same time existing major industries and big businesses.

The growth industries of the last half-century derived from the scientific discoveries of the middle and late nineteenth century.

The growth industries of the last decades of the twentieth century are likely to emerge from the knowledge discoveries of the first fifty and sixty years of this century: quantum physics, the understanding of atomic and molecular structure, biochemistry, psychology, symbolic logic.

The coming decades in technology are more likely to resemble the closing decades of the last century, in which a major industry based on new technology surfaced every few years, than they will resemble the technological and industrial continuity of the past fifty years.

We face major changes in the world’s economy.

In economic policies and theories, we still act as if we lived in an “international” economy, in which separate nations are the units, dealing with one another primarily through international trade and fundamentally as different from one another in their economy as they are different in language or laws or cultural tradition.

But imperceptibly there has emerged a world economy in which common information generates the same economic appetites, aspirations, and demands—cutting across national boundaries and languages and largely disregarding political ideologies as well.

The world has become, in other words, one market, one global shopping center.

Yet this world economy almost entirely lacks economic institutions; the only—though important—exception is the multinational corporation.

And we are totally without economic policy and economic theory for a world economy.

It is not yet a viable economy.

The failure of new major economies to join the ranks of “advanced” and “developed” nations has created a fissure between rich (and largely white) and poor (and largely colored) nations that may swallow up both.

The next decades must see drastic change.

Either we learn how to restore the capacity for development that the nineteenth century possessed in such ample measure—under conditions for development that are quite different—or the twentieth century will make true, as Mao and Castro expect, the prophecy of class war, the sidetracking of which was the proudest achievement of the generation before World War I.

Only the war would now be between races rather than classes.

The political matrix of social and economic life is changing fast.

Today’s society and polity are pluralistic.

Every single social task of importance today is entrusted to a large institution organized for perpetuity, and run by managers.

‘Where the assumptions that govern what we expect and see are still those of the individualistic society of eighteenth-century liberal theory, the reality that governs our behavior is that of organized, indeed overorganized, power concentrations.

Yet we are also approaching a turning point in this trend.

Everywhere there is rapid disenchantment with the biggest and fastest-growing of these institutions, modern government, as well as cynicism regarding its ability to perform.

We are becoming equally critical of the other organized institutions; revolt is occurring simultaneously in the Catholic Church and the big university.

The young everywhere are, indeed, rejecting all institutions with equal hostility.

We have created a new sociopolitical reality without so far understanding it, without, indeed, much thinking about it.

This new pluralist society of institutions poses political, philosophical, and spiritual challenges that go far beyond this book (or the author’s competence).

But the most important of the changes is the last one.

Knowledge, during the last few decades, has become the central capital, the cost center, and the crucial resource of the economy.

This changes labor forces and work, teaching and learning, and the meaning of knowledge and its politics.

But it also raises the problem of the responsibilities of the new men of power, the men of knowledge.

******

Yet neither economics nor technology, neither political structure nor knowledge and education, is the theme of this book.

The unifying common theme is the discontinuities that even a cursory glance at reality reveals.

They are very different, perhaps, from what the forecasts predict.

But they are even more different from what most of us still perceive as “today.”

Every single one of the views that this book records will be familiar.

Yet the social landscape that emerges when they are put together into one picture bears little resemblance to what all of us still see when we look around us.

Or, to change the metaphor, we, the actors, still believe we are playing Ibsen or Bernard Shaw — while it is the “Theater of the Absurd” in which we actually appear (and on TV rather than “live” on Broadway).

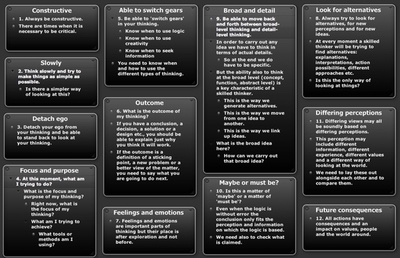

Most mistakes in thinking are mistakes in perception: Seeing only part of the situation; Jumping to conclusions; Misinterpretation caused by feelings

******

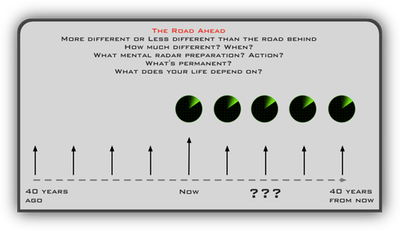

It is high fashion today to predict “the year 2000.”

We suddenly realize that we are closer to this milestone than we are to that fateful year 1933, when both Hitler and Roosevelt came to power.

And yet anyone middle-aged today still experiences 1933 as “current events.”

I envy the courage of the seers who tell us what 2000 may look like.

But I have no desire to emulate them.

I remember too well what the future looked like in 1933.

No forecaster could then have imagined our reality of 1968.

Nor could anyone, a generation earlier in 1900, have anticipated or forecast the realities of 1933.

All we can ever predict is continuity that extends yesterday’s trends into tomorrow.

What has already happened is the only thing we can project and the only thing that can be quantified.

But these continuing trends, however important, are only one dimension of the future, only one aspect of reality.

The most accurate quantitative projection never predicts the truly important: the meaning of the facts and figures in the context of a different tomorrow.

It would have been highly optimistic in 1950, less than twenty years ago, to predict that the United States could in this century reduce poverty to where fewer than one-tenth of white families and fewer than one-third of Negro families live below the “poverty threshold.”

Yet we achieved this by 1966.

Even in 1959, in the closing years of the Eisenhower Administration, it would have been considered almost utopian to predict that within one decade the number of families in poverty would be reduced by almost one-half, from more than 8 to fewer than 5 millions—the concrete achievement of the sixties.

Yet during this period we sharply raised the income level that defines “poverty.”

The correct figures could perhaps have been forecast.

But today, only ten years later, what controls the country’s mood and shapes its policies—not to mention its picture of itself—would have been quite unpredictable by any statistical, projective method: a change in the meaning, the quality, the perception of our experience.

In 1959 the accent was all on our affluence.

In 1969 it is all on the poor.

This book tries to look at these other dimensions, at the qualitative and the structural, the perceptions, the meaning and the values, the opportunities and the priorities.

It is limited in its subject matter to the social scene.

But there it takes a broad view, looking at economics and politics, at social issues, at technology, and at the universe of learning and knowledge.

Only incidentally does it concern itself, however, with those great realms of individual experience, the arts and man’s spiritual life.

This book does not project trends; it examines discontinuities.

It does not forecast tomorrow; it looks at today.

It does not ask, “What will tomorrow look like?”

It asks instead, “What do we have to tackle today to make tomorrow?”

Peter F. Drucker

Montclair, New Jersey

Summer,1968

The End of Continuity

No one knowing only the economic facts and figures of 1968 and of 1913—and ignorant both of the years in between and of anything but economic figures—would even suspect the cataclysmic events of this century such as two world wars, the Russian and Chinese revolutions, or the Hitler regime.

They seem to have left no traces in the statistics.

The tremendous economic expansion throughout the industrial world in the last two decades has by and large only made up for the three decades of stagnation between the two world wars.

And the expansion has in the main been confined to nations that were already “advanced” industrial nations by 1913—or were at least rapidly advancing.

Our time, all of us would agree, is a time of momentous changes—in politics and in science, in world view and in mores, in the arts and in warfare.

But in the one area where most people think the changes have been the greatest, the last half-century has been in reality a period of amazing and almost unparalleled continuity: in the economy.

The economic expansion of the last twenty years has been very fast.

But it has been carried largely by industries that were already “big business” before World War I.

It has been based on technologies that were firmly established by 1913 to exploit inventions made in the half-century before.

Technologically the last fifty years have been the fulfillment of the promises bequeathed to us by our Victorian grandparents rather than the years of revolutionary change the Sunday supplements talk about.

Imagine a good economist who fell asleep in July, 1914, just before “the guns of August” shattered the world of the Victorians.

He wakes up now, more than fifty years later, and, being a good economist, he immediately reaches for the latest economic reports and figures.

This Rip Van Winkle would be a mighty surprised man—not because the economy has changed so much, but because it has changed so very much less during fifty years than any economist (let alone a good one) would have expected.

The figures would show that by the mid-sixties all economically advanced countries had, on the whole, reached the levels of production and income they would have attained had the economic trends of the thirty or so years before 1914 continued, basically unchanged, for another fifty years.

The one important exception to this might be Russia, where production and income today are probably well below what the pre-1914 growth rates had promised.

We know the reason, of course.

It is the political straitjacket into which the Communists forced Russian agriculture just when the technological revolution got going on the farm.

As a result, Russia, in 1913 one of the world’s largest food exporters, now can barely feed her own population.

Yet she still keeps nearly half her people on the land—at least twice as many as would be needed had Russian farm productivity been allowed to grow at the rate at which it grew between 1900 and 1913.

All other countries that had reached by 1913 what is now called the “take-off point” in economic development—the United States, the countries of Western and Central Europe, and Japan—are today roughly where a long-range projection of the growth trends of the years between 1885 and 1913 would have put them half a century later, that is, today.

This is true even of Britain; by 1913 her growth had already slowed to a crawl.

Even more amazing: our Rip Van Winkle economist would find the economic geography of the world quite unchanged in its structure.

Every single area that is today a major industrial power was already well along the road to industrial leadership in 1913.

No major new industrial country has joined the club since.

Brazil, at least in its central region, may be on the threshold of emergence, but she is not there yet.

Otherwise, only areas that are, in effect, extensions of the old industrial regions, such as Canada, Mexico, and Australia, have grown to industrial stature, and, at that, mainly as satellite economies.

In the half-century before 1913, the economic map of the world had been changing as fast and as drastically as the physical map of the world had changed during the age of discovery in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Between 1860 and 1870, both the United States and Germany had surfaced as new, big industrial powers and had rapidly forged ahead of the old champion, Great Britain.

Twenty years later, Russia, Japan, the present Czechoslovakia, and the present Austria had soared aloft, with Northern Italy following closely behind.

The fact that economic development, which seemed so easy and effortless then, even for a non-Western country like Japan, has since World War I become so difficult as to be apparently unattainable is not only a fundamental economic contrast between our era and that of the Victorians and Edwardians.

It is also the greatest political threat today—comparable only to the threat of class war inside industrial society before 1913.

If our Rip Van Winkle economist should turn to industrial structure and technology, he would find himself equally (and equally unexpectedly) on familiar ground.

Of course, there are hundreds of products around that would be unfamiliar to him: electric appliances, TV sets, jet planes, antibiotics, the computer.

But in terms of economic structure and growth, the load is still being carried by the same industries and largely by the same technologies that carried it in 1913.

The main engine of economic growth in the developed countries during the last twenty years has been agriculture.

In all these countries (excepting only Russia and her European satellites), productivity on the farm has been increasing faster than in the manufacturing industries.

Yet the technological revolution in agriculture had begun well before 1913.

Most of the “new” agricultural technology—tractors, fertilizer, improved seeds and breeds—had been around for many years.

The “good” farmer of today has just about reached the productivity and output of the “model farm” of 1913.

Second only to farming as a moving force behind our recent economic expansion is steel.

World steel capacity has grown fivefold since 1946, with Russia and Japan in the lead.

But steel production had become synonymous with economic muscle well before World War I.

Almost all the steel mills built since World War II use processes that date back to the 1860's and were already considered obsolescent fifty years ago.

The automobile industry—probably number three in the growth parade today—was also well advanced when World War I started.

Henry Ford turned out a quarter-million Model T's in 1913—more than the Soviet Union has yet produced in any one year.

And there is not one major feature on any car anywhere today that could not have been found on some commercially available make in 1913.

The electrical apparatus, the telephone, and the organic-chemical industries were already giants fifty years ago.

General Electric, Westinghouse, Siemens, the Bell Telephone System, and the German chemical companies were by then well-established blue chips.

Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company and British Shell were hardly struggling infants; they were the “octopuses” of 1913 with tentacles into every country in the world.

And though electronics was just beginning its growth then, it was already large enough to spawn, in the British “Marconi Affair” of 1912, a scandal so big and juicy that it threatened the political life of the first of the new breed of “democratic” leaders, Lloyd George.

Of course, all around us there are new industries and new technologies.

But as the economist defines “importance”—that is, by contribution to gross national product, personal income, and employment—these new industries are still almost negligible, at least to the civilian economy.

The airplane began to make an economic impact only with the coming of jets in the 1960's.

Air freight is only now growing at a phenomenal rate.

When the big “jumbo jets” begin to fly around 1970, the freight plane may well, within a few years, make obsolete the oceangoing cargo ship just as the truck has broken the railroad monopoly on land in the last thirty years.

So far, however, air freight is still a lesser factor in world transportation than bullock or burro.

Only now, when IBM is turning them out at a rate of a thousand a month, are computers starting to have substantial economic impact.

The pharmaceutical industry has all but made over the practice of medicine in the last thirty years.

Thanks to new drugs, health care has become the “best buy” on the market and a universal demand; as a result health services and their financing are everywhere becoming a governmental concern, just as schooling went public 150 years ago when literacy first became a profitable investment for the individual.

Yet economically—that is, in terms of employment or of direct contribution to national product—the pharmaceutical industry is still hardly visible to the naked eye and is a pygmy next to such traditional industries as food processing, railroading, or textiles.

Of all the new industries only one has, so far, attained major economic importance (as the economist measures importance).

It is plastics.

Even plastics were looked upon until a very few years ago as “substitutes”—ersatz—rather than a major new industry and technology in their own right.

And even the plastics industry today is only a faint premonition of what the “materials” industry of tomorrow is likely to be, both economically and technologically.

The new industries with their new technologies loom much larger in our eyes than the old familiar steel mills and automobile assembly plants.

They capture our imagination and furnish the glamour stocks in our investment portfolios.

But if all of them (except plastics), with all their output and all their jobs, were taken out of the figures for the civilian economy, the difference would hardly show in national income or total employment, that is, in the figures by which the economist measures economic strength and growth.

An economist of 1913 could, therefore, have forecast the industry structure of the 1960's with reasonable accuracy.

Only no sane economist of that time would have dreamed of forecasting continuity.

The relative stability in technologies and industries during the last fifty years is in the sharpest imaginable contrast to the turbulence of the half-century before.

The fifty years that came to an end with World War I produced most of the inventions that underlie our modern industrial civilization.

Synthetic dyes (and with them the organic-chemical industry), the Bessemer steel process and the Siemens electrical generator came in the late 1850's and 1860's.

The electric light bulb and the phonograph were invented (both by Edison) in the 1870's.

In the same decade appeared the typewriter and the telephone, which together took respectable women out of the home and into the office and thus led, in another half-century, to female emancipation and suffrage.

In the 1880's came the automobile.

In the same decade came aluminum—together with the slightly older vulcanized rubber, the first truly new material since the Chinese first made paper around the time of Christ.

Marconi’s wireless and aspirin (the first effective synthetic drug and the beginning of the pharmaceutical industry) were developed in the 1890's, the Wright brothers’ airplane in 1903, the electronic tube (de Forrest and Armstrong) in 1912.

Most industrial technology today is an extension and modification of the inventions and technologies of that remarkable half-century before World War I.

This continuity, in turn, has made for stable industry structure.

Every one of the great nineteenth-century inventions gave birth, almost overnight, to a new major industry and to new big businesses.

These are still the major industries and big businesses of today.

The best example is the rebuilding of industrial Germany after World War II.

The same companies dominate the German economy today and are the blue chips of the Frankfurt Stock Exchange that dominated German economy and stock exchanges in 1913.

Their names are unchanged; their product scopes, their markets, their technologies are largely unchanged—they are only much, much bigger.

To be sure, this faithful, almost antiquarian, restoration of pre-World War I German industry overdid it.

The Krupp concern was rebuilt by the last bearer of the name to look as much as possible like the empire his grandfather had left behind around 1900—an empire of coal mines, steel mills, and shipyards—and had to be taken over by the banks under a government guarantee in 1967.

But the reason for failure was the old and familiar nemesis of industrial empire builders: financial overextension, rather than the ancestor worship of the last Krupp.

Indeed, even the technoeconomic “catastrophes” that we are so widely threatened with are still in the future rather than the present.

The “population explosion” has not, so far, caused large-scale famine and pestilence.

We would actually still worry a good deal about it unsalable surpluses” of farm crops if Russia had continued to increase farm productivity at the pre-World War I rate (let alone if Russian farm productivity had shown anything like the explosive growth of American agriculture).

And while we have the technological means to control population, not even the pill has so far had a major impact in the poor countries of rapid population growth.

The world of the New Left and of the hippies, of Op Art and of Mao Tse-tung’s Cultural Revolution, of H-bombs and moon rockets, seems further removed from the certainties and perceptions of the Victorians and Edwardians than they were from the Age of the Migration at the end of antiquity.

But in the economy, in industrial geography, industrial structure, and industrial technology, we are still very much the heirs of the Victorians.

Measured by the yardsticks of the economist, the last half-century has been an Age of Continuity—the period of least change in three hundred years or so, that is, since world commerce and systematic agriculture first became dominant economic factors in the closing decades of the seventeenth century.

The growth during this period of continuity has been great, especially in the countries that were already well advanced before 1913.

But the growth has been largely along lines that had been laid down well and truly in those distant days of our grandparents and great-grandparents.

What is amazing is perhaps not that it took a half-century for the work and thought of those earlier generations to bring full fruit.

It is that the generation of 1900, which we tend today to look down on as stodgy stick-in-the-muds, laid down economic foundations of such strength and excellence that they have prevailed over all the wickedness, criminal insanity, and suicidal violence of the last fifty years.

The towering economic achievements of today, the affluent, mass consumption economies of the advanced countries, their productivity and their technological powers, are built four-square on Victorian and Edwardian foundations and out of building blocks quarried then.

They are, above all, a fulfillment of the economic and technological promises of the Victorian and Edwardian eras and a testimony to their economic vision.

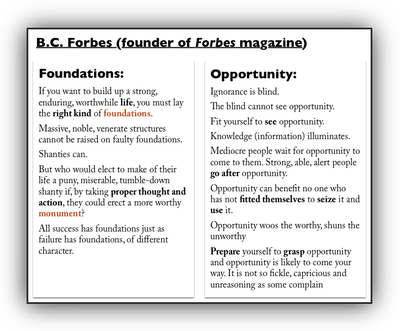

Now, however, we face an Age of Discontinuity in world economy and technology.

We might succeed in making it an age of great economic growth as well.

But the one thing that is certain so far is that it will be a period of change—in technology and in economic policy, in industry structures and in economic theory, in the knowledge needed to govern and to manage, and in economic issues.

While we have been busy finishing the great nineteenth-century economic edifice, the foundations have shifted under our feet.

The Need for Theory

The pluralist structure of modern society is independent, by and large, of political constitution and control, of social theory, or of economics.

It has, therefore, to be tackled as such.

It requires a political and social theory of its own.

This is true of each individual organization as well.

It too is new.

We have, of course, had large organizations for centuries.

The pyramids were built by highly organized masses of people.

Armies have often been large and highly organized.

But these organizations of yesterday—Lewis Mumford calls them the Megamachines*—were fundamentally different from the institutions of today.

Great architects designed the great pyramids-their names are recorded and they were worshiped as gods.

But other than those few artist-geometers, there were only unskilled manual laborers, peasants from the villages, who pulled the ropes to move the big stones.

Henry Ford’s River Rouge plant making the Model T was an organization of the same kind -a handful of bosses knew whatever was known, gave whatever orders were given, and made whatever decisions were made; the rest were unskilled manual laborers doing repetitive work.

The basic difference between the pyramid builders and Henry Ford’s men on the assembly line was that “scientific management” of the task made possible very high pay for the automobile worker.

But the work and its organization was the same, and Henry Ford was conscious of this in his insistence that he be the only “manager” in the Ford Motor Company.

Today’s organization (including today’s Ford Motor Company) is, however, principally a knowledge organization.

It exists to make productive hundreds, sometimes thousands, of specialized kinds of knowledge.

This is true of the hospital where we now have some thirty-odd or more health-care professions—each with its own course of study, its own diploma, and its own professional code and standards.

It is true of today’s business, of today’s government agency, and increasingly of today’s army.

In every one of them the bulk of the workers are hired not to do manual work but to do knowledge work.

The Egyptian fellahin who pulled at the ropes when Cheops’ supervisors barked out the order did not have to do any thinking and were not expected to have any initiative.

The typical employee in today’s large organization is expected to use his head to make decisions and to put knowledge responsibly to work.

But perhaps even more important: today’s knowledge organization is designed as a permanent organization.

All the large organizations of the past were short-lived.

They were called into being for one specific task and disbanded when the task had been accomplished.

They were temporary.

They were clearly the exception as well.

The great majority of people in earlier society were unaffected by them.

Today the great majority of people depend on organizations for their livelihood, their opportunities, and their work.

The large organization is the environment of man in modern society.

It is the source also of the opportunities of today’s society.

It is only because we have these institutions that we have jobs for educated people.

Without them we would be confined, as always in the past, to jobs for people without education, people who, whether skilled or unskilled, work with their hands.

Knowledge jobs exist only because permanent knowledge organization has become the rule.

At the same time, modern organization creates new problems as well; above all, problems of authority over people.

For authority is needed to get the job done.

What should it be?

What is legitimate?

What are the limitations?

There are also problems of the purpose, task, and effectiveness of each organization.

There are problems of management.

For the organization itself, like every collective, is a legal fiction.

It is individuals in the organization who make the decisions and take the actions which are then ascribed to the institution, whether it be the “United States,” the “General Electric Company,” or “Misericordia Hospital.”

There are problems of order and problems of morality.

There are problems of efficiency and problems of relationships.

And for none of them does tradition offer us much guidance.

The permanent organization in which varieties of knowledge are brought together to achieve results is new.

The organization as the rule rather than as the exception is new.

And a society of organizations is the newest thing of them all.

What is therefore urgently needed is a theory of organizations.

See the movement toward organic design.

Toward A Theory Of Organizations

In the spring of 1968, a witty book made headlines for a few weeks.

Entitled Management & Machiavelli,* it asserted that every business is a political organization and that, therefore, Machiavelli’s rules for princes and rulers are fully applicable to the conduct of corporation executives.

Of course, this is not a particularly new insight.

More than a century ago Anthony Trollope used the theme of Machiavellian politics in a British diocese to write one of the great Victorian classics, Barchester Towers.

C.P. Snow, especially in The Masters (1951), has presented the university as an interplay of power.

And the point that the corporation is a polity and a community fully as much as it is an economic organ has been made many times by now.☨

The suburban ladies at whom the reviews of Management & Machiavelli were largely aimed are probably fully aware that the bridge club and the PTA have nothing to learn about politicking from big business, or indeed from Machiavelli.

That every organization must organize power and must therefore have politics is neither new nor startling.

But during the last twenty years, nonbusinesses—government, the armed services, the university, the hospital—have begun to apply to themselves the concepts and methods of business management.

And this is indeed new.

This is indeed startling.

When the Canadian armed services were unified in the spring of 1968, the first meeting of general officers from all the services had as its theme “managing by objectives.”

Government after government has organized “administrative staff colleges” for its senior civil servants in which it tries to teach them “principles of management.”

And when 9,000 secondary-school principals of the United States met in the crisis year of 1968, with its racial troubles and its challenges to established curricula, they chose for their keynote speech, “The Effective Executive,” and invited an expert on business management to deliver it.

The British Civil Service, that citadel of the “arts degree” in the classics, now has a management division, a management institute, and management courses of all kinds.

Demand from nonbusiness organizations for the services of “management consultants” is rising a great deal faster than the demand from businesses.

What is new is the realization that all our institutions are “organizations” and have, as a result, a common dimension of management.

These organizations are complex and multidimensional.

They require thinking and understanding in at least three areas—the functional or operational, the moral, and the political.

The new general theory of a society of organizations will look very different from the social theories we are accustomed to.

Neither Locke nor Rousseau has much relevance.

Neither has John Stuart Mill or Karl Marx.

Making Organization Perform

How do organizations function and Operate?

How do they do their job?

There is not much point in concerning ourselves with any other question about organizations unless we first know what they exist for.

The functional or operational area by itself has three major parts, each a large and diverse discipline in its own right.

They have to do with goals, with management, and with individual performance.

1. Organizations do not exist for their own sake.

They are means: each society’s organ for the discharge of one social task.

Survival is not an adequate goal for an organization as it is for a biological species.

The organization’s goal is a specific contribution to individual and society.

The test of its performance, unlike that of a biological organism, therefore, always lies outside of it.

The first area in which we need a theory of organizations is, therefore, that of the organization’s goals.

How does it decide what its objectives should be?

How does it mobilize its energies for performance?

How does it measure whether it performs?

It is not possible to be effective unless one first decides what one wants to accomplish.

It is not possible to manage, in other words, unless one first has a goal.

It is not even possible to design the structure of an organization unless one knows what it is supposed to be doing and how to measure whether it is doing it.

Anyone who has ever tried to answer the question, “What is our business?”

has found it a difficult, controversial, and elusive task.

“We make shoes” may seem obvious and simple.

But it is a useless answer.

It does not tell anyone what to do.

Nor, equally important, does it tell anyone what not to do.

Are we primarily concerned with the conversion of leather into goods that consumers will want to pay for?

Or are we primarily move concerned with mass distribution?

Or are we in the fashion business?

“Shoes” are simply a vehicle.

What we actually do depends much less on the vehicle than on the specific economic satisfaction it is meant to carry and the specific contribution for which the business expects to get paid.

Is a company that makes and sells kitchen appliances, such as Electric ranges, in the food business?

Is it in the homemaking business?

Or is its main business really consumer finance?

Each answer might be the right one at a given time for a given company.

But each would lead to very different conclusions as to where the company should put its efforts and seek its rewards.

If the answer given is “the food business,” the company might go into preparing and marketing ready-cooked meals that require only heating to be served and eaten.

But, if the answer is “consumer finance,” the company might go out of manufacturing altogether and instead distribute a wide variety of high-cost consumer goods from wedding rings to trailer homes.

These, however, would be the vehicle to carry the real “product” of the company, which would be consumer credit.

In each of these definitions, different economic factors are seen as dynamic and as determining results.

Each, in turn, requires different abilities and defines both “market” and “success” differently.

Similarly, “patient care” might seem an obvious and simple answer for the hospital.

Hospital administrators, however, have found it impossible to define “patient care” or “health care.”

One reason why these questions are so difficult is that people differ in their judgments regarding the needs of the community.

They set different priorities.

There is also always a conflict between those who want to do better what is already being done and those who want to do different things.

In fact, it is never possible to give a “final” answer to the question, “What is our business?”

Any answer becomes obsolete within a short period.

The question has to be thought through again and again.

But if no answer at all is forthcoming, if objectives are not clearly set, resources will be splintered and wasted.

There will be no way to measure the results.

If the organization has not determined what its objectives are, it cannot determine what effectiveness it has and whether it is obtaining results or not.

The cost/ effectiveness concept which Robert McNamara introduced into the management of the American military forces while Secretary of Defense under President Kennedy was, above all, an attempt to force the military to think through objectives.

Starting out from the truism that everything requires scarce resources and therefore incurs a cost, McNamara demanded that costs be related to results.

The process disclosed at once that the military had not thought through what results it expected because it had not thought through the objectives of a strategy, of a command (e.g., the Tactical Air Force), or of a weapon.

Is the objective to win a war?

Or is it to prevent one?

What kind of a war and where?

These were the questions the cost/ effectiveness formula forced the generals and admirals to think through and to work out among themselves and with their civilian superiors.

Cost/ effectiveness could not make policy decisions.

But it did bring the confusion of policy and objectives into the open.

It did show both how vital the decision on objectives is and how difficult and risky it is.

There is no “scientific” way to set objectives for an organization.

They are rightly value judgments, that is, true political questions.

One reason for this is that the decisions stand under incurable uncertainty.

They are concerned with the future.