Learning

The learning explored on this page is broader than and in many cases different from school learning or a “human resource” sub-function carrying a learning related title.

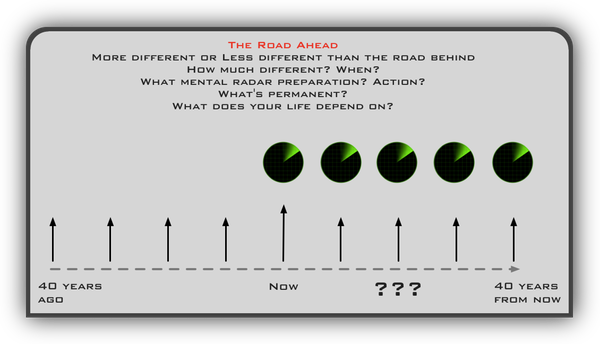

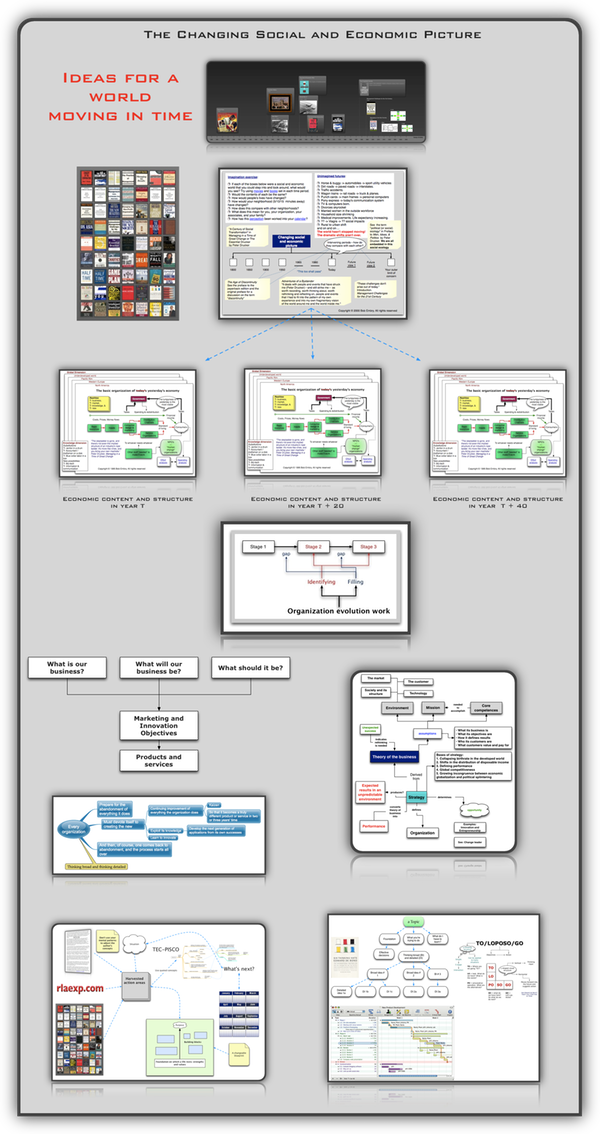

This page presents a broad multi-dimensional landscape across time.

Learning is the only way to move forward — acquiring the ability to do the “right things” — throughout time.

“It’s not the will to win, but the will to prepare to win that makes the difference.” — Bear Bryant

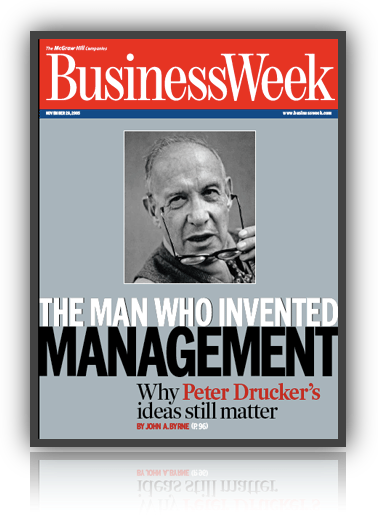

“If You Keep Doing What Worked in the Past You’re Going to Fail” — A Class With Drucker

“To know something,

to really understand something important,

one must look at it from sixteen different angles.

People are perceptually slow,

and there is no shortcut to understanding;

it takes a great deal of time.” read more

“Companies devote a lot of time, effort and money to corporate training—with little to show for it.

U.S. firms spent about $156 billion on employee learning in 2011, the most recent data available, according to the American Society for Training and Development. But with little practical follow-up or meaningful assessments, some 90% of new skills are lost within a year, some research suggests.” — WSJ online

A critical question for leaders is, “When do you stop pouring resources

into things that have achieved their purpose?”

The most dangerous traps for a leader are those near-successes

where everybody says that if you just give it another big push

it will go over the top. One tries it once. One tries it twice.

One tries it a third time. But, by then it should be obvious

this will be very hard to do.

So, I always advise my friend Rick Warren,

“Don’t tell me what you’re doing, Rick.

Tell me what you stopped doing.” — Drucker on Leadership

The failed strategy and abandonment

(calendarize this?)

Time usage decisions: Problems or Opportunities?

The Individual

In Entrepreneurial Society

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

A little misguided, but a very capable individual :)

Knowledge specialty

… One implication of this is that individuals will increasingly have to take responsibility for their own continuous learning and relearning, for their own self-development and for their own careers.

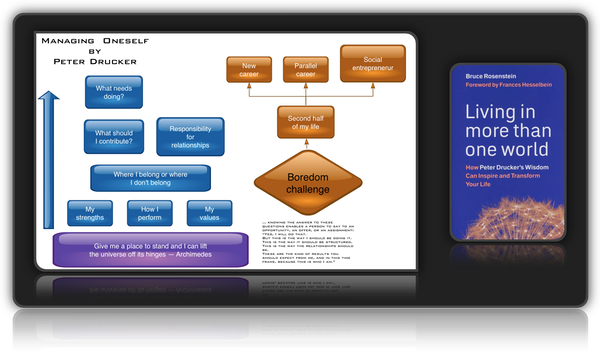

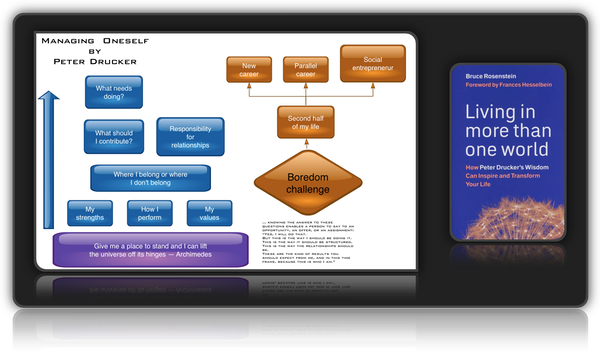

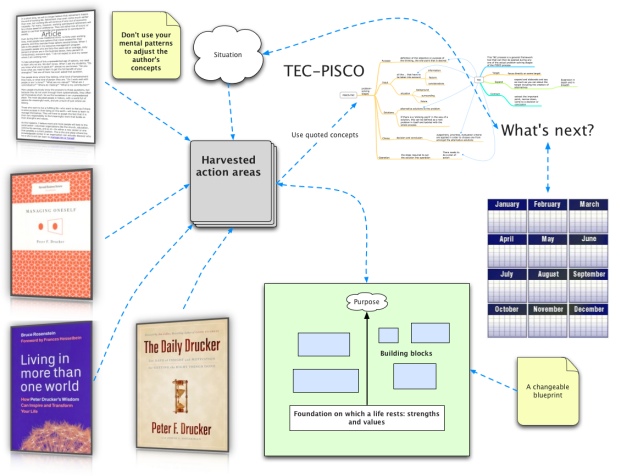

See Managing Oneself as an individual

They can no longer assume that what they have learned as children and youngsters will be the “foundation” for the rest of their lives.

It will be the “launching pad” — the place to take off from rather than the place to build on and to rest on.

They can no longer assume that they “enter upon a career” which then proceeds along a pre-determined, well-mapped and well-lighted “career path” to a known destination—what the American military calls “progressing in grade.”

The assumption from now on has to be that individuals on their own will have to find, determine, and develop a number of “careers” during their working lives.

And the more highly schooled the individuals, the more entrepreneurial their careers and the more demanding their learning challenges.

The carpenter can still assume, perhaps, that the skills he acquired as apprentice and journeyman will serve him forty years later.

Physicians, engineers, metallurgists, chemists, accountants, lawyers, teachers, managers had better assume that the skills, knowledges, and tools they will have to master and apply fifteen years hence are going to be different and new. (see knowledge specialty)

Indeed they better assume that fifteen years hence they will be doing new and quite different things, will have new and different goals and, indeed, in many cases, different “careers.”

And only they themselves can take responsibility for the necessary learning and relearning, and for directing themselves.

Tradition, convention, and “corporate policy” will be a hindrance rather than a help. …

Read more

Joe’s Journal: On Learning How to Learn

The source page http://thedx.druckerinstitute.com/2012/09/learning-to-learn/ has gone missing

“Managing oneself is a REVOLUTION in human affairs.

It requires new and unprecedented things from the individual, and especially from the knowledge worker.

For, in effect, it demands that each knowledge worker think and behave as a chief executive officer.

It also requires an almost 180-degree change in the knowledge workers’ thoughts and actions from what most of us still take for granted as the way to think and the way to act.”

–Peter F. Drucker

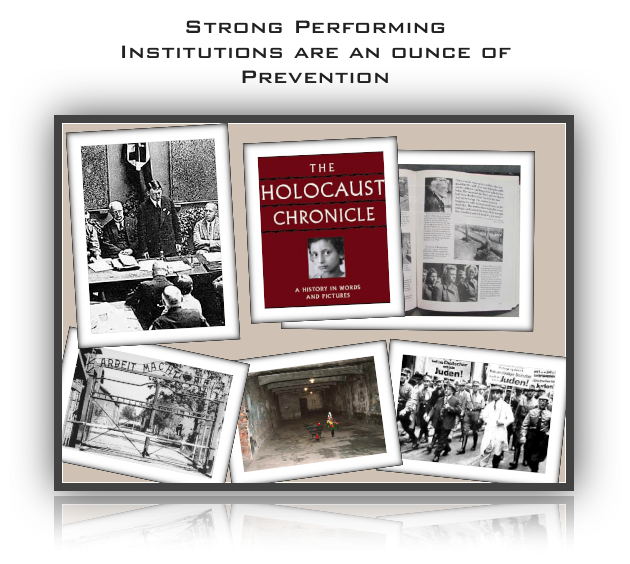

Peter Drucker recognized that we are living in a time characterized by rapid change, the likes of which we have never seen before.

The lessons are clear: Keep up on your field or face obsolescence.

Success in this era of a global knowledge society requires that one create his or her future rather than becoming a victim of change.

A good way to ensure that is to learn how to learn.

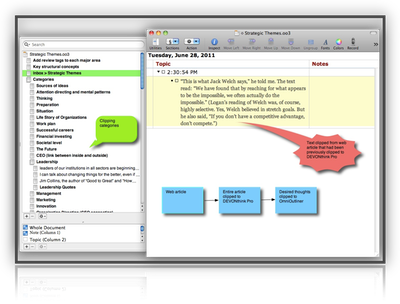

As knowledge itself is becoming obsolete very rapidly, it is essential for knowledge workers to build on their capacity for learning through useful aids such as reading synoptically, which I have discussed before.

This will help you trace a topic through multiple books by getting the questions clear and by imposing those questions on various authors.

Second, become an expert in using information technology to improve the effectiveness of using your time.

Understand where to look for the information you need and how to gather the elements for fully understanding a subject.

For example, to understand Drucker on social responsibility you must read all of his books dealing with the topic and see where he ended up, which in my opinion is defining “Good Capitalism” versus “Bad Capitalism”; recognizing the limits of government; and encouraging professional management in the social sector.

Next, stretch yourself to learn a subject you did not know before and by which you were intimidated.

Then finally, you will need to ask yourself essential questions such as, “Where am I likely to make my best and most satisfying contribution?”

Seek areas outside your current organization to act on the answers.

Try to achieve work-life balance when all of the pressures are running the other way.

Remember, wealthy people are not always happy people.

So, be sure that you know the answer to “How much is enough?”

Then try to fulfill the deepest longings of your nature.

All of this means that we should think like effective executives as we manage ourselves, and not limit that thinking only to how we manage our organizations.

—Joe Maciariello

Joe’s Journal: On Knowledge Work and Learning

The source page http://thedx.org/2011/02/joes-journal-on-knowledge-work-and-learning/ is gone missing

“Demanding of knowledge workers that they define their own task and its results is necessary because knowledge workers must be autonomous.

As knowledge varies among different people, even in the same field, each knowledge worker carries his or her own unique set of knowledge.

Knowledge work requires both autonomy and accountability”.

–Peter F. Drucker

It’s true that for any society to develop it first needs manual productivity.

But with the changes in society and technology today, we need to be sure that we understand the life of the knowledge workers as well as the assembly line workers.

Knowledge work has brought about a need for a new kind of manager.

In this new climate a manager needs to understand his place in the larger system or organization.

For example if you’re medical chief in a hospital, your own specialty might be gastroenterology, but your role still requires that you manage people who are experts in oncology, pathology, neuroscience, orthopaedics, pediatrics and so on.

You can’t possibly expect to know how to do their job.

And you certainly wouldn’t tell any of those experts on your team how to do their job, because you can’t.

You have to give your team autonomy as their manager, but you also have to be able to make the whole unit work.

You have to understand the mission and understand management well enough to integrate the various disciplines into the larger mission, but you cannot expect to know as much about the details of the various jobs under your management.

Managers need to give the knowledge workers a firm understanding of the mission, and then allow the workers themselves to define the tasks and results.

There are multiple ways to define open-heart surgery: You could tally how many surgeries you’ve completed, or you could tally how many were successful.

Once you define results, you have to associate quality with them, and that’s where the manager or executive has a role.

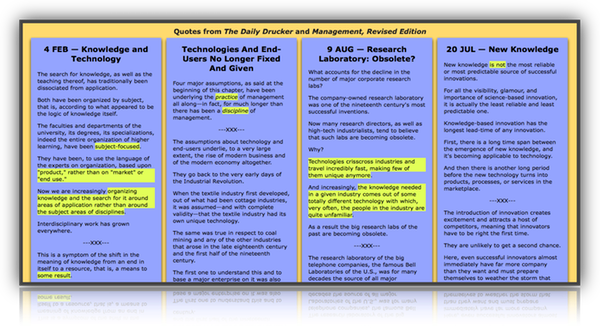

In 1966 Drucker wrote the Effective Executive and directed it to the knowledge workers.

He explained that executives are people who make contributions to the results, but it’s the worker who does the work and who must learn to manage him or herself for productivity.

Results and quality and opportunities for continuous learning are also up to the knowledge worker.

In order to improve and to keep developing the critical skills for their roles, workers need to be pushed, not beyond their limits but to the fullest extent of their capabilities.

I had to really be pushed and push myself in my latest book project.

I had to be my own manager in the sense that I knew that in order to get to the next level of analysis I’d have to stretch and challenge myself.

I had to tap back into the lessons of Mortimer Adler on syntopical reading and I had to rethink what I know about research and I relearned a lot about the power and complexity of online research.

I had to really tap into my own learning processes and get better at a few things.

I think it’s important for knowledge workers and for students to learn not just information and content that is useful right now, but to learn how to learn so that they can keep up with the ever-changing knowledge out there.

We all need to understand the process of learning in order to thrive in a knowledge society.

You know, just before Peter died he said to me that he thought his ideas would only live on for about another ten years.

I think he was wrong about that, but I also think that his more important legacy is the example he set by the way he worked.

The staying power in all of his books and ideas is his process.

–Joe Maciariello

rlaexp.com site search: continuing education

For what purposes #1

in what areas, for what purposes #2,

from what sources,

in what amounts, at what intervals?

Create a tree chart?

From Drucker’s life as a knowledge worker

“Whenever a Jesuit priest or a Calvinist pastor does anything of significance—making a key decision, for instance—he is expected to write down what results he anticipates.

Nine months later he traces back from the actual results to those anticipations.

That very soon shows him what he did well and what his strengths are.

It also shows him what he has to learn and what habits he has to change.

Finally, it shows him what he has no gift for and cannot do well.

I have followed that method for myself now for 50 years.

It brings out what one’s strengths are—and that is the most important thing an individual can know about himself or herself.

It brings out areas where improvement is needed and suggests what kind of improvement is needed.

Finally, it brings out things an individual cannot do and therefore should not even try to do.

To know one’s strengths, to know how to improve them, and to know what one cannot do—they are the keys to continuous learning.”

(calendarize this)

Very easy to get lost and stumble into …

The world is full of options

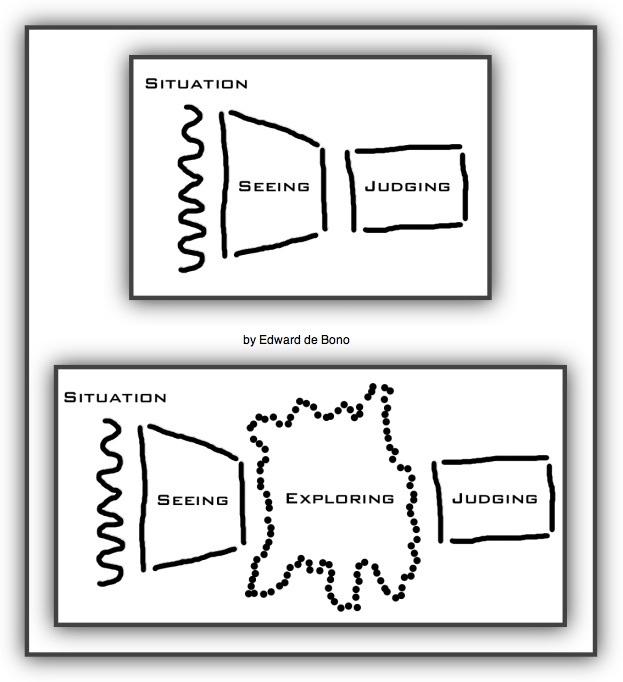

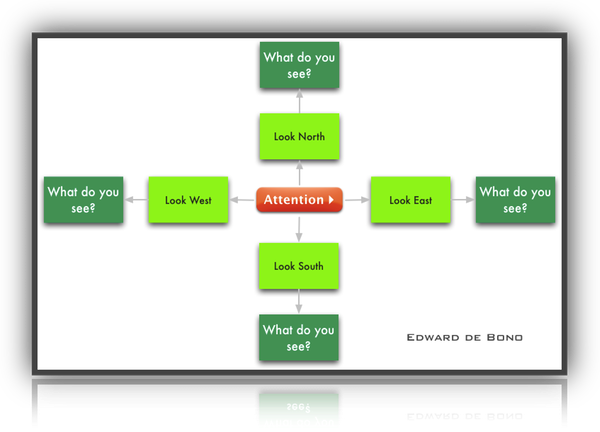

Exploration is attention directing.

Writing out what you see

is different from saying it

mentally or verbally. It makes you decide.

And then having the courage to dig deeper and test.

Additionally, what are the implications of what you see?

Maybe this will help you SEE!

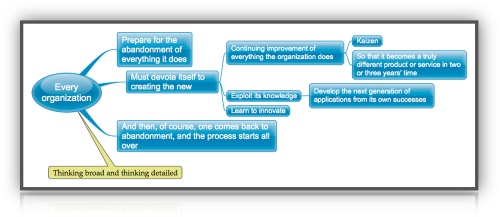

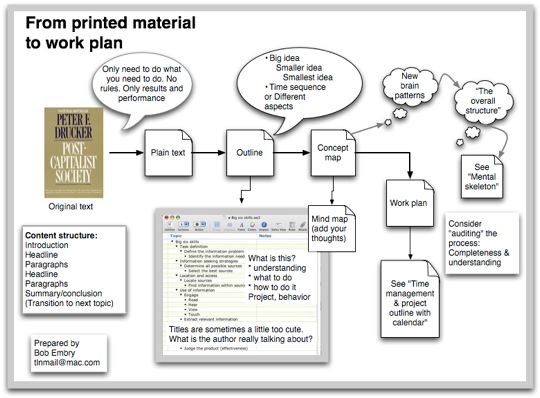

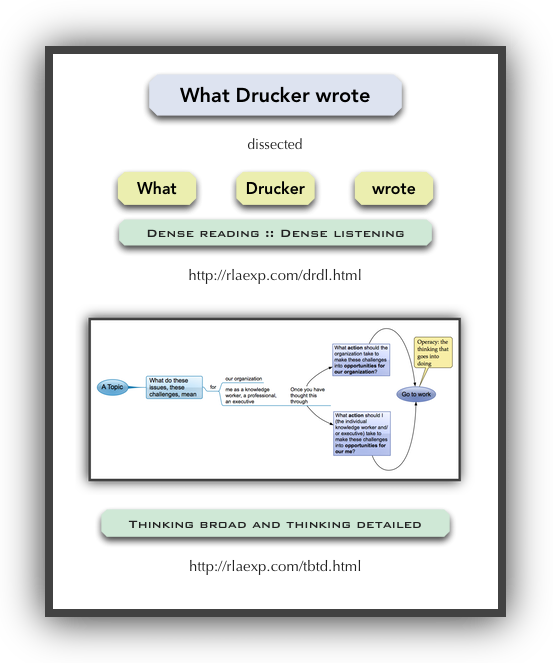

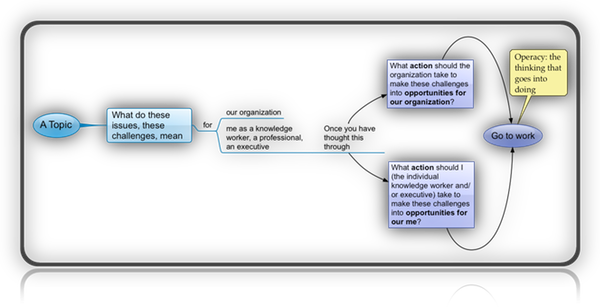

Dense reading and Dense listening and

Thinking broad and Thinking detailed

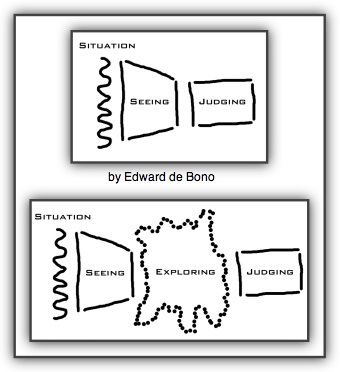

by Edward de Bono

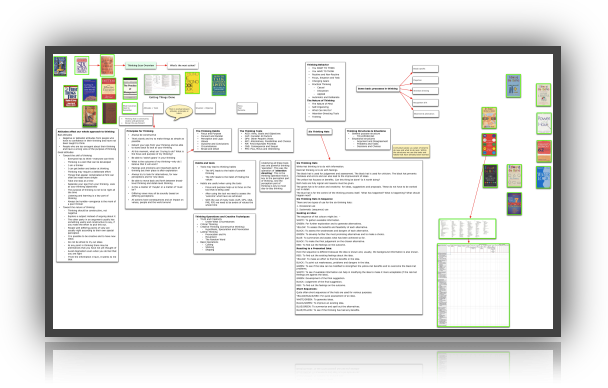

Along a brain road, sentences or thoughts may be springboards to further thinking (what kind?) that suggest or imply calendarization — working something out in time.

Larger then Edward de Bono

Radar system and radar list

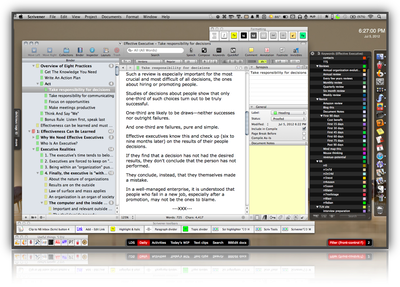

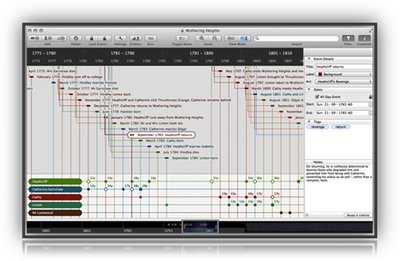

Scrivener and Aeon Timeline could also be used

for note-taking and sequencing

Important brainscapes to explore:

Peter Drucker: A political and social ecologist Peter Drucker: A political and social ecologist

What do you want to be remembered for? (after you’ve explored this page) What do you want to be remembered for? (after you’ve explored this page)

CEO work area landscapes (and then?) CEO work area landscapes (and then?)

Drucker on learning Drucker on learning

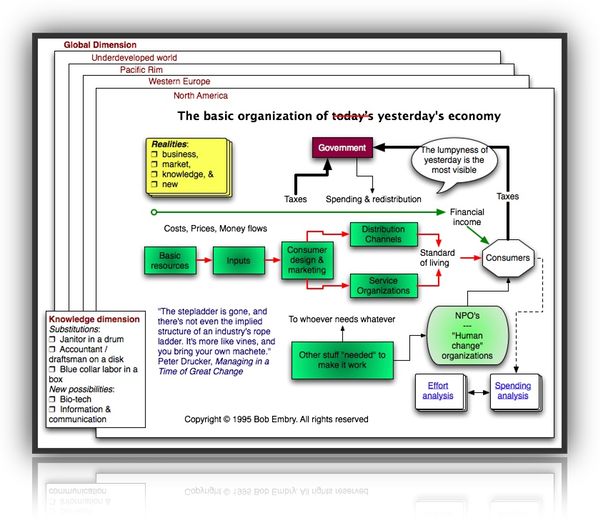

We are already embedded in a

knowledge society, a society of organizations, and a network society …

This means a radical change in structure for the organizations of tomorrow.

It means that the big business, the government agency, the large hospital, the large university will not necessarily be the one that employs a great many people.

It will be the one that has substantial revenues and substantial results—achieved in large part because it itself does only work that is focused on its mission; work that is directly related to its results; work that it recognizes, values, and rewards appropriately.

The rest it contracts out.

The function of organizations is to make knowledges productive.

Organizations have become central to society in all developed countries because of the shift from knowledge to knowledges.

The more specialized knowledges are, the more effective they will be.

… “For the major new insights in every one of the specialized knowledges arise out of another, separate specialty, out of another one of the knowledges.

Both economics and meteorology are being transformed at present by the new mathematics of chaos theory. Geology is being profoundly changed by the physics of matter; archaeology, by the genetics of DNA typing; history, by psychological, statistical, and technological analyses and techniques.” Chapter 48, Management, Revised Edition

… But now the traditional axiom that an enterprise should aim for maximum integration has become almost entirely invalidated.

One reason is that the knowledge needed for any activity has become highly specialized.

… snip, snip …

It is therefore increasingly expensive, and also increasingly difficult, to maintain enough critical mass for every major task within an enterprise.

And because knowledge rapidly deteriorates unless it is used constantly, maintaining within an organization an activity that is used only intermittently guarantees incompetence.

The second reason why maximum integration is no longer needed is that communications costs have come down so fast as to become insignificant.

… snip, snip …

This has meant that the most productive and most profitable way to organize is to disintegrate.

This is being extended to more and more activities.

Chapter 6 Management, Revised Edition

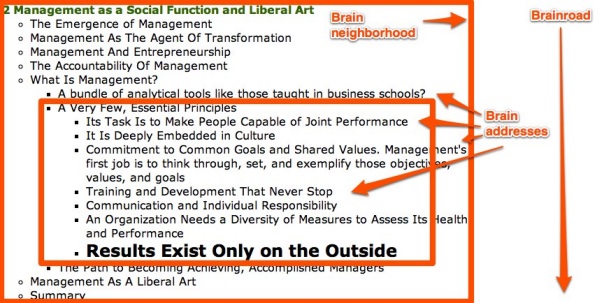

Management must also enable the enterprise and each of its members to grow and develop as needs and opportunities change.

Every enterprise is a learning and teaching institution.

Training and development must be built into it on all levels—training and development that never stop. — Chapter 2 of Management, Revised Edition by Peter Drucker

Many big companies are currently building their own in-house education facilities.

I advise caution here.

The greatest danger to the big company is the belief that there is a right way, a wrong way, and our way.

In-house training tends to emphasize and strengthen that view.

Skills, yes; teach them in-house.

But for purposes of broadening the horizon, questioning established beliefs, and for organized abandonment, it is better to be confronted with diversity and challenge.

For these, managers should be exposed to people who work for different companies and do things in different ways — Afterword of Managing for the Future.

Education can no longer be confined to the schools.

Every employing institution has to become a teacher.

Large Japanese employers—government agencies and businesses—already recognize this.

The country that is again in the lead, however, is the United States, where employers—business, government agencies, the military—spend as much money and effort on the education and training of their employees, and especially the most highly educated ones, as do all the country’s colleges and universities together.

European transnational companies too are increasingly taking on the continuing education of their employees and especially of managers. — The New Realities

Information challenges

Chapter 24 — Developing Management and Managers in Management, Revised Edition

School and Education as Society’s Center in A Century of Social Transformation — Emergence of Knowledge Society

Universities

“Pedagogues become intoxicated with the enlightenment of the students. For the smile of learning on the student’s face is more addictive than any drug.”

“When a subject becomes obsolete, we make it a required course.”

Interviewer: What is your opinion of universities today?

Peter Drucker: Unprintable.

Interviewer: Why is that?

Peter Drucker: The American university has become arrogant.

It has become lazy. It has become self-righteous.

And above all, it believes that the student exists for the sake of the university.

PFD Forbes

From Drucker on Asia —

A Dialogue Between Peter Drucker and Isao Nakauchi

Needs of continuing education

Another change that is predictable, though entirely different, is that a new focus for school and learning is emerging: the continuing education of already-educated adults.

Precisely because knowledge is becoming the central resource of a modern economy, continuous learning is essential.

For knowledge, by its very definition, makes itself obsolete every few years, and then knowledge workers have to go back to school.

They may be store managers and retail buyers, like the ones who attend your marketing university, or physicians, or engineers, but every few years they have to refresh and renew their knowledge.

Otherwise they risk becoming obsolescent.

This will have tremendous impact on the university and on schools.

It will force us to accept the fact that, in the knowledge society, learning is life-long and does not end with graduation.

In fact, that is when it begins.

It will also have tremendous impact on employing institutions

In effect, these are still changes within the system, rather than changes of the system.

What is an educated person?

Your question: ‘What is an educated person?’ goes directly to the meaning of learning, the meaning of education the essence of the system.

I am afraid, however, that I cannot answer that question.

It is going to be our challenge for the next one hundred years.

In one way, I very much hope that we will be able to maintain the link with tradition and with the past, which is implicit in the traditional definition of an educated person.

The Japanese definition was developed by the Bunjin of the mid-Edo period, and the Western definition was developed by the great educators of Europe’s seventeenth century.

These definitions still largely underlie the education that you and I received.

I do not believe that this, by itself, is enough, for these definitions assume that learning is finite.

They assume that an educated person is somebody who has learned while young, and stopped learning when going to work.

We will now, I think, have to build into our definition what one of the great men of the Meiji period tried to establish.

Yukichi Fukuzawa, truly one of the most important figures of the nineteenth century, strongly believed and preached that an educated person is one who is able and eager to continue learning.

This will be particularly important as more and more young people are likely to start as specialists or, at least, will make their early careers as specialists.

Young people not knowing how to connect their knowledge

A specialist is a knowledgeable person, but he is not automatically an educated person.

An educated person is capable of relating an area of special knowledge to the universe of knowledge and of human experience.

This, if I may say so, is what today’s younger people are not able to do.

As you know, I teach mostly successful and fairly advanced executives, from business, from government, from non-profit institutions of all kinds—typically men and women in their early or mid forties—who have been successful enough to hold important executive positions, usually in large organizations.

They know a great deal, but they do not know that they know it.

They cannot, for instance, relate something they know about economics to their own work.

They cannot relate what they know about their own work to any other field of knowledge.

They do not know how to connect.

This is just as true of my Japanese students as it is of my American or European students.

These executives are usually brilliant people.

They are sent to our Executive Management Program by their employers because they are highly promising executives.

They have an outstanding educational record as a rule, and ten or fifteen years of successful, practical experience behind them, but they find it difficult to relate their experience to what their colleagues in the classroom tell them about their experiences.

They find it difficult to relate what they have learned, let us say, about psychology, to their own work in managing people.

Knowledge and human development

Such people know a great many things, but they are not educated in the sense that they can reflect this knowledge on their own work or development, their own personality.

This, I submit, is the great challenge ahead of us, for the next generation of educational leaders.

Without it, we will have a great deal of specialized competence, but little else.

The challenge ahead of us is to make knowledge again a means to human development.

The challenge is to go beyond knowledge as tools and to recover education as the road to wisdom.

I try to do this in my classroom and with my students.

It is the one reason why I still teach at my age.

Even if I am successful and I have great doubts—I would not know how to teach this to others, let alone how to convert this into a system, a curriculum, an organized educational effort.

This, in a way, is what being an educated person always meant.

This is what Liberal Arts always meant.

It is, in effect, what education, as distinct from knowledge competence, always meant and will, again have to mean.

When Louis V. Gerstner, Jr. took over IBM they were spending “bunches” of money on both employee development and R & D.

He said they employed more Nobel Laureates than most countries.

In spite of these efforts there was no real effective learning taking place.

Gerstner is credited with saving IBM from going out of business in the early 1990s.

The subsequent refocusing on the IT services business (which grew to nearly 50% of the IBM’s revenues), the embrace of the Internet as a business phenomenon, and a broad effort to revive the company’s culture are widely seen as having resulted in one of the most remarkable turnarounds in business history.[4]

In his memoir, Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?, he describes his arrival at the company in April 1993, when an active plan was in place to dis-aggregate the company.

The prevailing wisdom of the time held that IBM’s core mainframe business was headed for obsolescence.

The company’s own management was in the process of allowing its various divisions to rebrand and manage themselves — the so-called “Baby Blues.”

Gerstner reversed this plan, realizing from his previous experiences at RJR and American Express that there remained a vital need for a broad-based information technology integrator.

His decision to keep the company together was the defining decision of his tenure, as these gave IBM the capabilities to deliver complete IT solutions to customers.

Services could be sold as an add-on to companies that had already bought IBM computers, while barely profitable pieces of hardware were used to open the door to more profitable deals.[5]

While IBM had been credited with making the personal computer (PC) a mainstream product, the PC’s reliance on Intel chips and Microsoft software meant that IBM could no longer monopolize this market.

Outgoing IBM chairman and CEO John Fellows Akers, as an IBM lifer, was excessively immersed in its corporate culture and loyalty to traditional ways which masked the threats to the company.[6][7]

However as an outsider, Gerstner had no emotional attachment to long-suffering products that IBM developed in order to try to regain control of the PC market.

Gerstner wrote that his colleagues were “unwilling or unable to accept” that OS/2 was a “resounding defeat” as it “was draining tens of millions of dollars, absorbing huge chunks of senior management’s time, and making a mockery of our image", despite its technical superiority to the dominant Microsoft Windows 3.0.

By the end of 1994, IBM ceased new development of OS/2 software.

IBM withdrew from the retail desktop PC market entirely, which had become unprofitable due to price pressures in the early 2000s, and sold the PC division to Lenovo in 2005, just a few years after Gerstner stepped down as CEO.[8]

To Gerstner, focusing on the desktop PC ran counter to IBM’s view of where the tech world was headed.[9]

In his memoir, Gerstner described the turnaround as difficult and often wrenching for an IBM culture that had become insular and balkanized.

After he arrived, over 100,000 employees were laid off from a company that had maintained a lifetime employment practice from its inception.

Layoffs and other tough management measures continued in the first two years of Gerstner’s tenure, but the company was saved, and business success has continued to grow steadily since then.

... snip, snip ...

Following his success in IBM, Gerstner has also become a mentor to Howard Stringer, CEO of Sony Corporation to (attempt) turn around the Japanese corporation. — Wikipedia — needs to be updated for recent developments

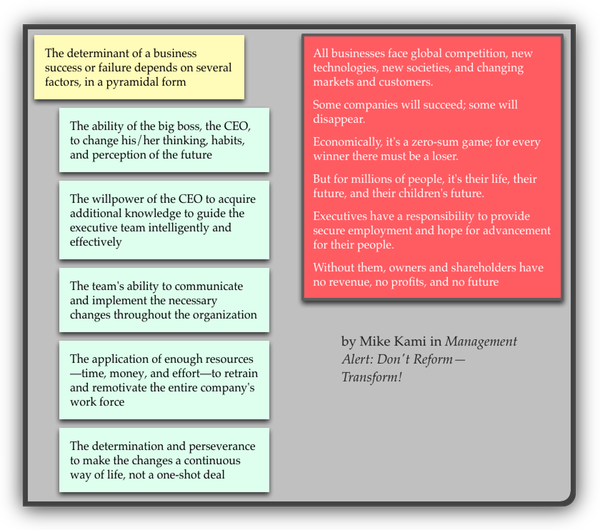

Mike Kami's determinants of success.

Kami was head of planning for IBM and Xerox during their growth phases

Larger view of image below

Management Alert: Don't Reform — Transform!

Managing in the Next Society et cetera

From Drucker on Asia —

A Dialogue Between Peter Drucker and Isao Nakauchi

Victims of success

Very few businesses can prosper even five or seven years without substantial change and massive rethinking of the very concepts on which they are based.

There are exceptions, to be sure, but they are rare.

It is by no means sure that it is a blessing for a business to enjoy long decades of continuity without challenge to its fundamental concepts and assumptions.

There is an old Chinese proverb:

‘Whom the gods want to destroy, they give forty years of success.’

Business history amply proves the wisdom of this old saying.

There are a few businesses around with a basic theory that goes back a century.

There is the universal bank (founded almost simultaneously around 1870 in Germany and in Japan) and the zaibatsu invented by Mitsubishi (and reborn after World War II as keiretsu).

Both concepts are clearly in crisis today, and are rapidly losing their effectiveness.

In the US, the four most successful businesses of this century were, respectively, the Bell Telephone System (AT&T), which alone, of all major telephone systems in the world remained privately-owned and did not become nationalized; Sears Roebuck, for almost half a century the world’s most successful retailer; General Motors; and IBM.

The Bell Telephone System was conceived and designed around 1910 when its predecessor was on the verge of bankruptcy.

Sears Roebuck, as it came to dominate the American retail scene, was designed in the early 1920s, as was General Motors.

And IBM was designed right after World War II.

For seventy years, the Bell Telephone System knew nothing but growth and success.

Sidebar: Continuous improvement is considered a recent Japanese invention — the Japanese call it kaizen.

But in fact it was invented almost eighty years ago, and in the US.

From World War I until the early 1980s when it was dissolved, the American Telephone Company (the Bell System) applied ‘continuous improvement’ to every one of its activities and processes, whether it was installing a telephone in a home or manufacturing switchgear.

For every one of these activities Bell defined results, performance, quality, and cost.

For everyone it set an annual improvement goal.

Bell managers were not rewarded for reaching these goals.

Those who did not reach them were out of the running, and were rarely given a second chance. — Drucker on Asia - A Dialogue Between Peter Drucker and Isao Nakauchi

For more than fifty years, Sears Roebuck and General Motors knew nothing but growth and success.

For forty years, IBM knew nothing but growth and success.

All four looked invincible, but when the time came for them to change, they proved impotent and ineffectual.

They became the victims of their own success.

Fortune’s top 500 companies

Businesses that go unchallenged for long decades are rare exceptions.

The great majority, no matter how successful, need to think through their basic assumptions much sooner.

The great majority, moreover, then find it almost impossible to change.

The business which, after ten years of continuing success, retains the capacity to change and to maintain its effectiveness, is in the minority.

It may not disappear, but it is likely to become an ‘also ran’ and to fall way behind.

The American magazine Fortune has for more than forty years published each year a list of the 500 top manufacturing companies in the US.

During these forty years, one-third of the companies in the original list have disappeared from it altogether — either because they have been liquidated or merged or because they have become insignificant.

Another third has lost position in the list, that is, has dropped from being a major to become a relatively minor business.

Only one-third have maintained themselves in the list, that is, in their position in the American economy.

The threat of continuing success

Every one of these companies that has been able to prosper for four decades has had to change fundamentally. Yet, the last forty years have been years of great continuity and, generally, years of tremendous prosperity, not only in the American economy but in the world economy.

What is needed is not only the capacity to overcome adversity. Equally important, and equally needed, is the capacity to take advantage of opportunity, and this, too, is equally threatened by continuing success, threatened by complacency.

An example of an automobile company

The best examples are recent ones.

One is the recent inability of the world’s most successful automobile companies to see, let alone to take advantage of, the sharp shift on the part of the American automobile buyer to sports-utility vehicles, minivans and pick-up trucks.

General Motors should have been the foremost beneficiary.

For when the shift began, in the early 1980s, General Motors had by far the best-designed vehicles of this kind, enjoyed the best reputation in the market, and had the lowest production costs.

Yet, General Motors simply missed the market.

Sports-utility vehicles, mini-vans and pick-up trucks were not considered ‘passenger cars’ and were not included as such in the monthly statistics of automobile sales.

No-one in General Motors’ top management fifteen years ago, therefore, even realized that these ‘non-passenger cars’ were where the market was growing.

But Toyota and Nissan equally missed this opportunity.

By the late 1980s, the Japanese-made automobile had established itself in the American market as the market leader and as the quality standard.

It seemed to be invincible.

Again, because sports-utility vehicles, mini-vans and pickup trucks were not classified as ‘passenger vehicles’, the Japanese missed the market shift in the US just as much as General Motors did.

The opportunity was exploited by the two weaker American automobile companies, Ford and Chrysler, both of which in the mid-1980s, seemed totally unable to compete against either the Japanese or their much bigger American rival.

This explains, by the way, why in the last five years neither General Motors nor the Japanese have been able to grow in the American market three have been losing ground steadily.

Even though all three now have the right products on the market, the three are still steadily losing market share in the American automobile market.

What is probably more important, they are steadily losing their leadership image.

It is, thus, no accident that the management literature has increasingly concerned itself with the management of change and with revitalizing business enterprise.

The first book on these subjects was probably my work Managing For Results in 1964.

Analysis of the entire business and its basic economics always shows it to be in worse disrepair than anyone expected.

The products everyone boasts of turn out to be yesterday’s breadwinners or investments in managerial ego.

Activities to which no one paid much attention turn out to be major cost centers and so expensive as to endanger the competitive position of the company.

What everyone in the business believes to be quality turns out to have little meaning to the customer.

Important and valuable knowledge either is not applied where it could produce results or produces results no one uses.

I know more than one executive who fervently wished at the end of the analysis that he could forget all he had learned and go back to the old days of the “rat race” when “sufficient unto the day was the crisis thereof.”

But precisely because there are so many different areas of importance, the day-by-day method of management is inadequate even in the smallest and simplest business.

Because deterioration is what happens normally—that is, unless somebody counteracts it—there is need for a systematic and purposeful program.

There is need to reduce the almost limitless possible tasks to a manageable number.

There is need to concentrate scarce resources on the greatest opportunities and results.

There is need to do the few right things and do them with excellence.

Managing for Results by Peter Drucker

What Is My Contribution?

from Management, Revised Edition

To ask, “What is my contribution?” means moving from knowledge to action.

The question is not, “What do I want to contribute?”

It is not, “What am I told to contribute?”

It is, “What should I contribute?”

This is a new question in human history.

Traditionally, the task was given.

It was given either by the work itself—as was the task of the peasant or the artisan.

Or it was given by a master or a mistress, as was the task of the domestic servant.

And, until very recently, it was taken for granted that most people were subordinates who did as they were told.

The advent of the knowledge worker is changing this, and fast.

Knowledge workers will have to learn to address the question, “What should my contribution be?”

Only then should they ask, “Does this fit my strengths?

Is this what I want to do?”

And, “Do I find this rewarding and stimulating”

The best example of this I know of is the way Harry Truman repositioned himself when he became president of the United States, upon the sudden death of Franklin D. Roosevelt at the end of World War II.

Truman had been picked for the vice presidency because he was totally concerned with domestic issues.

For it was then generally believed that with the end of the war—and the end was clearly in sight—the United States would return to an almost exclusive concern with domestic affairs.

Truman had never shown the slightest interest in foreign affairs, knew nothing about them, and was kept in total ignorance of them.

He was still totally focused on domestic affairs when, within a few weeks after his ascendancy, he went to the Potsdam Conference after Germany surrendered.

There he sat for a week, with Winston Churchill on one side and Joseph Stalin on the other, and realized, to his horror, that foreign affairs would dominate, but also that he knew absolutely nothing about them.

He came back from Potsdam convinced that he had to give up what he wanted to do and instead had to concentrate on what he had to do, that is, concentrate on foreign affairs.

He immediately put himself into school with General George Marshall and Dean Acheson as his tutors.

Within in a few months, he was a master of foreign affairs, and he, rather than Churchill or Stalin, created the postwar world—with his policy of containing Communism and pushing it back from Iran and Greece; with the Marshall Plan that rescued Western Europe; with the decision to rebuild Japan; and finally, with the call for worldwide economic development.

By contrast, Lyndon Johnson lost both the Vietnam War and his domestic policies because he clung to “What do I want to do?” instead of asking himself “What should my contribution be?”

Johnson, like Truman, had been entirely focused on domestic affairs.

He, too, came into the presidency wanting to complete what the New Deal had left unfinished.

He very soon realized that the Vietnam War was what he had to concentrate on.

But he could not give up what he wanted his contribution to be.

He splintered himself between the Vietnam War and domestic reforms—and he lost both.

One more question has to be asked to decide “What should I contribute?”—“Where and how can I have results that make a difference?”

The answer to this question has to balance a number of things.

Results should be hard to achieve.

They should require “stretching,” to use the present buzzword.

But they should be within reach.

To aim at results that cannot be achieved—or can be achieved only under the most unlikely circumstances—is not being “ambitious.”

It is being foolish.

At the same time, results should he meaningful.

They should make a difference.

And they should be visible and, if at all possible, measurable.

Here is one example from a nonprofit institution.

A newly appointed hospital administrator asked himself the question, “What should my contribution be?”

The hospital was big and highly prestigious.

But it had been coasting on its reputation for thirty years and had become mediocre.

The new hospital administrator decided that his contribution should be to establish a standard of excellence in one important area within two years.

And so he decided to concentrate on turning around the Emergency Room and the Trauma Center—both big, visible, and sloppy.

The new hospital administrator thought through what to demand of an Emergency Room, and how to measure its performance.

He decided that every patient who came into the Emergency Room had to be seen by a qualified nurse within sixty seconds.

Within twelve months that hospital’s Emergency Room had become a model for the entire United States.

And its turnaround also showed that there can be standards, discipline, and measurements in a hospital—and within another two years, the whole hospital had been transformed.

The decision that answers “What should my contribution be?” thus balances three elements.

First comes the question, “What does the situation require?”

Then comes the question, “How could I make the greatest contribution with my strengths my way of performing, my values, to what needs to be done?”

Finally, there is the question, “What results have to be achieved to make a difference?”

This then leads to the action conclusions:

what to do,

where to start,

how to start,

what goals and deadlines to set.

Throughout history, few people had any choices.

The task was imposed on them either by nature or by a master.

And so in large measure was the way in which they were supposed to perform the task.

But so also were the expected results—they were given.

To “do one’s own thing” is not freedom.

It is license.

It does not have results.

It does not contribute.

But to start out with the question, “What should I contribute? gives freedom.

It gives freedom because it gives responsibility.

Take responsibility for communications

The second thing to do to manage oneself and to become effective is to take responsibility for communications.

After people have thought through what their strengths are, how they perform, what their values are, and, especially, what their contribution should be, they then have to ask, Who needs to know this?

On whom do I depend?

And who depends on me?”

And then one goes and tells all these people—and tells them in the way in which they receive a message, that is, in a memo if they are readers, or by talking to them if they are listeners, and so on.

Most of the “personality conflicts” in organizations arise from the fact that one person does not know what the other person does, or does not know how the other person does his or her work, or does not know what contribution the other person concentrates on and what results he or she expects.

And the reason that they do not know is that they do not ask and, therefore, are not being told.

This reflects human stupidity less than it reflects human history.

It was unnecessary until very recently to tell any of these things to anybody.

Everybody in a district of the medieval city plied the same trade—there was a street of goldsmiths and a street of shoemakers and a street of armorers.

One goldsmith knew exactly what every other goldsmith was doing; one shoemaker knew exactly what every other shoemaker was doing; one armorer knew exactly what every other armorer was doing.

There was no need to explain anything.

The same was true on the land, where everybody in a valley planted the same crop as soon as the frost was out of the ground.

There was no need to tell one’s neighbor that one was going to plant potatoes—that, after all, was exactly what the neighbor did too, and at the same time.

And those few people who did things that were not “common,” the few professionals, for instance, worked alone, and also did not have to tell anybody what they were doing.

Today the great majority of people work with others who do different things.

The marketing vice president may have come out of sales and know everything about sales.

But she knows nothing about promotion and pricing and advertising and packaging and sales planning, and so on—she has never done any of these things.

Those who work under her must make sure that the marketing vice president understands what they are trying to do, why they are trying to do it, how they are going to do it, and what results to expect.

If the marketing vice president does not understand what these high-grade knowledge specialists are doing, it is primarily their fault, and not that of the marketing vice president.

They have not told her.

They have not educated her.

Conversely, it is the marketing vice president’s responsibility to make sure that every one of the people she works with understands how she looks on marketing, what her goals are, how she works, and what she expects of herself and of every one of them.

Even people who understand the importance of relationship responsibility often do not tell their associates and do not ask them.

They are afraid of being thought presumptuous, inquisitive, or stupid.

They are wrong.

Whenever anyone goes to his or her associates and says, “This is what I am good at.

This is how I work.

These are my values.

This is the contribution I plan to concentrate on and the results I should be expected to deliver,” the response is always, “This is most helpful. But why haven’t you told me earlier?“

And one gets the same reaction if one then asks, “And what do I need to know about your strengths, how you perform, your values, and your proposed contribution?”

In fact, a knowledge worker should request of people with whom he or she works—whether as subordinates, superiors, colleagues, team members—that they adjust their behavior to the knowledge worker’s strengths and to the way the knowledge worker works.

Readers should request that their associates write to them, listeners should request that their associates first talk to them, and so on.

And again, whenever that is done, the reaction of the other person will be, “Thanks for telling me.

It’s enormously helpful.

But why didn’t you ask me earlier?”

Organizations are no longer built on force.

They are increasingly built on trust.

Trust does not mean that people like one another.

It means that people can trust one another.

And this presupposes that people understand one another.

Taking relationship responsibility is therefore an absolute necessity.

It is a duty.

Whether one is a member of the organization, a consultant to it, a supplier to it, a distributor, one owes relationship responsibility to everyone with whom one works, on whose work one depends, and who, in turn, depends on one’s own work.

Chapter 45, Management, Revised Edition

Find “learn” on the following pages:

Might also try “educat” or “school” or “knowledg” for variants

Putting More Now Into The Internet (online continuing education) Putting More Now Into The Internet (online continuing education)

Peter Drucker’s My Life as a Knowledge Worker Peter Drucker’s My Life as a Knowledge Worker

Management, Revised Edition Management, Revised Edition

User’s guide to MBO User’s guide to MBO

How to guarantee non-performance How to guarantee non-performance

Peter’s Principles Peter’s Principles

Information challenges Information challenges

Drucker’s book outlines Drucker’s book outlines

The Shifting Knowledge Base in The New Realities see below The Shifting Knowledge Base in The New Realities see below

The Accountable School in Post-Capitalist Society The Accountable School in Post-Capitalist Society

Find “educat” in Drucker on Asia — A Dialogue Between Peter Drucker and Isao Nakauchi Find “educat” in Drucker on Asia — A Dialogue Between Peter Drucker and Isao Nakauchi

Practical Thinking Practical Thinking

New thinking New thinking

Josh Abrams Josh Abrams

Contrast the references above with the idea of memorizing some words, feeding them back on a test and then forgetting them.

Chapter 24, Management, Revised Edition “Developing Management and Managers”

Plenty of learning takes place in managing oneself. Learning what your strengths are and how you learn are important achievements. Do you know what you need to learn to get the full benefits of your strengths?

The Educated Person

Knowledge management

While Rafael Nadal is playing someone (except Novak Djokovic) he is very good at learning how to win.

Edward Jones: What did you learn?

A search of my site found “learning” mentioned on 140 pages and 40 PDFs

See the Drucker books below. Get Kindle versions. Do key word searches for “learn” and then “measurements” then “expect happen”

Feedback has to be built into the decision to provide a continuous testing, against actual events, of the expectations that underlie the decision. This is a learning process.

Decisions are made by people.

People are fallible; at their best, their works do not last long.

Even the best decision has a high probability of being wrong.

Even the most effective one eventually becomes obsolete

Oct 13 — The Daily Drucker

Try combining a conceptual resource with brainroad and calendarization thinking

Larger

From Managing the Non-Profit Organization

How do you define performance in the school?

ALBERT SHANKER: The way to deal with this is to ask: What kind of human being are we trying to produce?

Most educators deal with the question very narrowly in terms of test scores, SAT scores, or narrow performance.

But essentially performance in education occurs along three dimensions.

One, of course, is knowledge.

The second dimension, I would say, is being able to enter the world as a participating citizen and perform within the economy.

The third has to do with the growth of the individual and participation in the cultural life of society.

Unfortunately, we don’t do a very good job of even getting close to measuring these gains.

PETER DRUCKER: But it makes sense to say that unless a person has those tangible, measurable, knowledge skills, a foundation is lacking.

Somehow, one has to set priorities for defining what achievement is.

ALBERT SHANKER: I think the priority is to assess achievement longer range.

When you measure small gains each semester or each year, you get down to things that don’t mean very much.

Rather trivial things that a student can study for an exam.

They don’t mean anything a week later.

They’re not even remembered later on.

PETER DRUCKER: I think I’m a living example of this.

My school grades were always excellent.

I learned very little and studied less, but I knew how to take exams.

ALBERT SHANKER: Let me illustrate what learning is not and what it is.

Teachers are required to give a course in Nature, so they put bird charts around the room.

They show flash cards and have the children give the names of the birds.

The end result is an examination where the students regurgitate the names of the birds.

But the kids don’t remember the names very long; all that’s there a few months later is a permanent dislike of birds.

In the Boy Scouts, when I was a youngster, they had a bird-study merit badge.

You actually had to see forty different birds.

You soon find you can’t do that by walking across the street to a park.

You have to get up early in the morning and go to a swamp or woods.

You don’t want to do it alone, so you find one or two friends who will go with you.

Soon you find that the birds you see out there don’t look the way they do in pictures.

What happens over the months of going out with your friends and looking at these birds is you begin to feel a sense of power.

You can see birds around you that no one else can see.

A key problem for schools is to organize learning for youngsters in such a way that it doesn’t become something memorized and instantly forgotten, but something that becomes part of you.

I have never met anyone who went through this experience in the Boy Scouts for whom it didn’t remain a pretty lasting interest.

PETER DRUCKER: The implication of this is, first, that you put the learning responsibility on the student rather than the teaching responsibility on the teacher.

Is that central to the way you see performance?

ALBERT SHANKER: Essentially, the way schools are organized is to get a lot of activity and work on the part of teachers while the students sit and, you hope, listen.

You hope that they are remembering something.

And you create a few punishments or rewards in terms of grades or leaving students back.

Without that responsibility and without that engagement by students, the results are very, very meager.

PETER DRUCKER: For hundreds of years, then, our emphasis has been on how well the teachers teach rather than on how well the student learns?

ALBERT SHANKER: The school is organized on the assumption that the student is a thing to be worked on, not that the student is the worker.

A school is something like an office.

That is, the students are required to read reports and write reports.

It’s more like an office than any other place.

But it’s an office in which the student is given a desk and told, “Your boss there, the teacher, will tell you what to do.

But every forty minutes you will move to a different room and you will be given a different desk and you will be given a different boss who will give you different work to do.”

Now, no one would organize an office that way.

The student is not being viewed as a worker who has to be engaged, but as raw material passing through a factory.

Well, of course, it doesn’t work because that’s not the way the process of learning goes on.

PETER DRUCKER: I’ve been a teacher-watcher since fourth grade, when I had the great good luck of two exceptional teachers.

And I’ve been a teacher myself since I was twenty.

I have yet to see a great teacher who teaches children.

All the great teachers I’ve seen made no distinction between children and adults.

Only the speed is different.

Whatever the task is, you do it on an adult level.

The task may be a beginner’s task; the standards are not.

The fourth-grade teacher whom I still remember once said many years later that there are no poor students; there are only poor teachers.

That would imply that the job of the teacher is to find the strengths of the student and put them to work, rather than to look at the student as somebody whose deficiencies have to be repaired.

From Managing for the Future

see the remainder of “Afterword: 1990s and beyond” for more on learning

The Learning Society Is Taking Over

In the place of the blue-collar world is a society in which access to good jobs no longer depends on the union card, but on the school certificate.

Between, say, 1950 and 1980 it was economically irrational for a young American male to stay at school.

In three months a 16-year-old school leaver with a job at a unionized steel plant could be taking home more money than his university-educated cost accountant brother would make in his life.

Those days are over.

From now on the key is knowledge.

The world is becoming not labor intensive, not materials intensive, not energy intensive, but knowledge intensive.

Japan today produces two and a half times the quantity of manufactured goods as 25 years ago with the same amount of energy and less raw material.

In large part this is due to the shift to knowledge-intensive work.

The representative product of the 1920s, the automobile, at the time had a raw material and energy content of 60 percent.

The representative product of the 1980s is the semiconductor chip, which has a raw material and energy content of less than 2 percent.

The 1990s equivalent will be biotechnology, also with a content of about 2 percent in materials and energy, but with a much higher knowledge content.

Assembling microchips is still fairly labor intensive (10 percent).

Biotechnology will have practically no labor content at all.

Moreover, fermentation plants generate energy rather than consume it.

The world is becoming knowledge intensive not just in the labor force, but in process.

Knowledge is always specialized.

The oboist in the London Philharmonic Orchestra has no ambition to become first violinist.

In the last 100 years only one instrumentalist, Toscanini, has become a conductor of the first rank.

Specialists remain specialists, becoming ever more skillful at interpreting the score.

Yet specialism carries dangers, too.

Truly knowledgeable people tend by themselves to overspecialize, because there is always so much more to know.

As part of the orchestra, that oboist alone does not make music.

He or she makes noise.

Only the orchestra playing a joint score makes music.

For both soloist and conductor, getting music from an orchestra means not only knowing the score, but learning how to manage knowledge.

And knowledge carries with it powerful responsibility, too.

In the past, the holders of knowledge have often used (abused) it to curb thinking and dissent, and to inculcate blind obedience to authority.

Knowledge and knowledge people have to assume their responsibilities.

Most Education Does Not Deliver Knowledge …

The advent of the knowledge society has far-ranging implications for education.

Schools will change more in the next 30 years than they have since the invention of the printed book.

One reason is modern learning theory.

We know how people learn, and that learning is not at all the same thing as teaching.

We know, for instance, that no two human beings learn in the same way.

The printed book set off the greatest explosion in learning and the love of learning the world had ever seen.

But book learning was for adults.

The printed book is basically adult-friendly.

In contrast, the new learning tools are child-friendly, as anyone with a computer-using eight- or nine-year-old child will know.

By the age of eleven most children except the freaks begin to be bored with the computer: for them it is just a tool.

But up to that age, children treat computers as extensions of themselves.

The advent of such powerful tools alone will force the schools to change.

… So Organizations Must Do It Themselves

But there is another consideration.

For the first time in human history it really matters whether or not people learn.

When the Prince Regent asked Marshal Blücher if he found it a great disadvantage not to be able to read and write, the man who won the battle of Waterloo for Wellington replied:

“Your Royal Highness, that is what I have a chaplain for.”

Until 1914 most people could do perfectly well without such accomplishments.

Now, however, learning matters.

The knowledge society requires that all its members be literate, not just in reading, writing, and arithmetic, but also in (for example) basic computer skills and political, social, and historical systems.

And because of the vastly expanding corpus of knowledge, it also requires that its members learn how to learn.

There will—and should—be serious discussion of the social purpose of school education in the context of the knowledge society.

That will certainly help to change the schools.

In the meantime, however, the most urgent learning and training must reach out to the adults.

Thus, the focus of learning will shift from schools to employers.

Every employing institution will have to become a teacher.

Large numbers of American and Japanese employers and some Europeans already recognize this.

But what kind of learning?

In the orchestra the score tells the employees what to do; all orchestra playing is team playing.

In the information-based business, what is the equivalent of this reciprocal learning and teaching process?

One way of educating people to a view of the whole, of course, is through work in cross-functional task forces.

But to what extent do we rotate specialists out of their specialties and into new ones?

And who will the managers, particularly top managers, of the information-based organization be?

Brilliant oboists, or people who have been in enough positions to be able to understand the team, or even young conductors from smaller orchestras?

We do not yet know.

Above all, how do we make this terribly expensive knowledge, this new capital, productive?

The world’s largest bank reports that it has invested $1.5 billion in information and communications systems.

Banks are now more capital intensive than the biggest manufacturing company.

So are hospitals.

Only 50 years ago a hospital consisted of a bed and a sister.

Today a fair-sized U.S. hospital of 400 beds has several hundred attending physicians and a staff of up to 1,500 paramedics divided among some 60 specialities, with specialized equipment and labs to match.

None, or very few, of these specialisms even existed 50 years ago.

But we do not yet know how to get productivity out of them; we do not yet know in this context what productivity means.

In knowledge-intensive areas we are pretty much where we were in manufacturing in the early nineteenth century.

When Robert Owen built his cotton mills in Scotland in the 1820s, he tried to measure their productivity.

He never managed it.

It took 50 more years until productivity as we understand it could be satisfactorily defined.

We are currently at about the Robert Owen stage in relation to the new organizations.

We are beginning to ask about productivity, output, and performance in relation to knowledge.

We cannot measure it.

We cannot yet even judge it, although we do have an idea of some of the things that are needed.

How, for instance, do famous conductors build a first-rate orchestra?

They tell me that the first job is to get the clarinetist to keep on improving as a clarinetist.

She or he must have pride in the instrument.

The players must be craftsmen first.

The second task is to create in the individuals a pride in their common enterprise, the orchestra:

“I play for Cleveland, or Chicago, or the London Philharmonic, and that is one of the best orchestras in the world.”

Third, and this is what distinguishes a competent conductor from a great one, is to get the orchestra to hear and play that Haydn symphony in exactly the way the conductor hears it.

In other words, there must be a clear vision at the top.

This orchestra focus is the model for the leader of any knowledge-based organization

Notes clipped from chapters in linked books below. Some are out of order, but it will give an indication of future interest. (calendarize this?)

- The Shifting Knowledge Base (from The New Realities)

- All members of society need to be literate

- Reading, writing, and arithmetic

- Elementary computer skills

- Considerable understanding of technology, [Technology, Management and Society] its dimensions, its characteristics, its rhythms

- Considerable knowledge of a complex world in which boundaries of town, nation, and country no longer define one’s horizons

- Knowledge of one’s roots and community is however also becoming more important

- Only through the school—through organized, systematic, purposeful learning—can this information be converted into knowledge and become the individual’s possession and tool

- The knowledge society also requires that all its members learn how to learn

- There is an infinity of knowledge careers to choose from

- Ten years out of school are already “obsolescent” if they have not refreshed their knowledge again and again

- There is no way in which even the best school system with the longest years of schooling can possibly prepare students for all these choices

- All it can do is to prepare them to learn

- The post-business, knowledge society is a society of continuing learning and second careers

- To restore the capacity of the American school to provide universal literacy on a high level—well beyond that of the elementary school—will therefore have to be a first priority

- School and education will be central to American public life and American politics for years to come

- Giving students the capacity and the knowledge to keep on learning, and the desire to do it

- We don’t learn for school but for life

- What they still know of the subjects—whether mathematics, a foreign language, or history—in which they got such wonderful marks

- How people learn how to learn

- Make learners achieve

- Focus on the strengths and talents of learners so that they excel in whatever it is they do well

- No one can predict what a ten-year-old will be doing ten or fifteen years later

- One cannot even at that stage eliminate many options

- The school has to endow students with the basic skills they will need whichever way they choose to go

- They have to be able to function

- One cannot build performance on weaknesses, even on corrected ones

- One can build performance only on strengths

- They will also have to be the “leaders.”

- That requires ethos, values, and morality

- Without theses it conveys indifference, irresponsibility, cynicism

- There is no such thing as a “finished education” in the knowledge society

- It requires that people with advanced schooling come back to school again and again and again

- Continuing education, especially of highly schooled people such as physicians, teachers, scientists, managers, engineers, and accountants, is certain to be a major growth industry of the future

- So far, however, schools and universities, except in the United States and Great Britain to a degree, still view continuing education with grave misgivings if they do not shun it altogether

- Education can no longer be confined to the schools

- Every employing institution has to become a teacher

- The Educated Person

- An educated person is equipped both to lead a life and to make a living

- It can afford neither the schooled barbarian who makes a good living but has no life worth living

- Nor the cultured amateur who lacks commitment and effectiveness

- Education will have to transmit “virtue” while teaching the skills of effectiveness

- But they do respond with enthusiasm to history, to the great tradition altogether, if offered to them in a form that makes it relevant to their experiences, their society, their needs

- Older people, the participants in continuing education, usually cannot get enough of ethics, of history, of great novels, of anything that helps them understand their own experience, the challenges they face in their own life and in their own work

- And they also crave the fundamentals of science and technology, the ways and values of government and politics; in short, everything that constitutes a broad liberal education

- But we have to make all this meaningful and to project it on the realities in which people live

- There is need to make the “humanities” again what they are supposed to be: lights to help us see and guides to right action

- The advent of the knowledge society will force us to focus the wisdom and beauty of the past on the needs and ugliness of the present

- This is what scholars and humanists contribute to the making of a life

- For almost nothing in our educational systems prepares them for the reality in which they will live, work, and become effective

- Elementary skills of effectiveness as members of an organization

- Ability to present ideas orally and in writing (briefly, simply, clearly)

- Ability to work with people (as individuals)

- Ability to shape and direct one’s own work, contribution, career

- And generally skills in making organization a tool for one’s own aspirations and achievements and for the realization of values

- From Teaching to Learning

- What can be taught has to be taught and will not be learned otherwise

- But what can be learned must be learned and cannot be taught

- We know first that different people learn differently

- Indeed, learning is as personal as fingerprints; no two people learn exactly alike

- Each has a different speed, a different rhythm, a different attention span

- If an alien speed, rhythm, or attention span is imposed on the learner, there is little or no learning; there are only fatigue and resistance

- But we also know that different people learn different subjects differently

- Most of us learned the multiplication table behaviorally, that is, by drill and repetition

- But mathematicians do not “learn” the multiplication table; they perceive it

- Some things do have to be taught—and not only values, insight, meaning

- One learns a subject

- One teaches a person

- The New Learning Technology

- “The medium is the message,” is surely an exaggeration

- But the “medium” does imply what message can be sent and received

- Equally important, it determines what messages cannot be sent and received

- And the medium is rapidly changing

- There are more hours of pedagogy in one thirty-second commercial than most teachers can pack into a month of teaching

- The subject matter of the TV commercial is quite secondary; what matters is the skill, professionalism, and persuasive power of the presentation

- The teacher’s job will be to help, to lead, to set example, to encourage; it may not primarily be to convey the subject matter itself

- To create the desire to learn which, in the last analysis, is the essence of being educated

- What Is Knowledge?

- Specialization was the royal road both to the acquisition of new knowledge and to its transmission

- Elsewhere specialization is becoming an obstacle to the acquisition of knowledge and an even greater barrier to making it effective

- Academia defines knowledge as what gets printed

- But surely this is not knowledge; it is raw data

- Knowledge is information that changes something or somebody—either by becoming grounds for action, or by making an individual (or an institution) capable of different and more effective action

- And this, little of the new “knowledge” accomplishes

- We no longer accept the old axiom that it is the duty of people of knowledge to make themselves understood

- What matters is that the learning of the academic specialist is rapidly ceasing to be “knowledge.”

- It is at best “erudition” and at its more common worst mere “data.”

- The disciplines and the methods that produced knowledge for two hundred years are no longer fully productive, at least outside of the natural sciences

- The rapid growth of cross-disciplinary and interdisciplinary work would indeed argue that new knowledge is no longer obtained from within the disciplines around which teaching, learning, and research have been organized in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries

- The Accountable School (from Post-Capitalist Society)

- It requires numeracy; it requires a basic understanding of science and of the dynamics of technology; it requires an acquaintance with foreign languages

- It also requires learning how to be effective as a member of an organization, as an employee

- Unless the school successfully imparts these skills to the young learner, it has failed in its crucial duty: to give beginners self-confidence, to give them competence, and to make them capable, a few years hence, to perform and achieve in the post-capitalist society, the knowledge society

- Learning to learn

- Subjects may matter less than the students’ capacity to continue learning and their motivation to do so

- We need a discipline of learning

- They lead their students to achievements so great that it surprises the achiever and creates excitement and motivation especially the motivation for rigorous, disciplined, persistent work and practice which continued learning requires

- There are few things more boring than practicing scales

- Yet the greater and the more accomplished pianists are, the more faithfully do they practice their scales, hour after hour, day after day, week after week

- Similarly, the more skilled surgeons are, the more faithfully do they practice tying sutures, hour after hour, day after day, week after week

- Pianists do their scales for months on end for an infinitesimally small improvement in technical ability

- But this then enables them to achieve the musical result they already hear in their inner ear

- Achievement is addictive

- The achievement that motivates is doing exceptionally well what one is already good at

- Achievement has to be based on the student’s strengths

- The proudest products of the traditional school, “the all-around A students,” are the ones who satisfy mediocre standards across the board

- They are not the ones who achieve; they are the ones who comply

- There is a second process knowledge to be taught by the schools—or at least learned in them: the process needed to obtain what in the last chapter I called the “yield” from knowledge

- This requires that the process—the concepts, the diagnosis, the skills—will have to be made teachable, or at least learnable

The society of organizations demands of the individual decisions regarding himself.

At first sight, the decision may appear only to concern career and livelihood.

“What shall I do?” is the form in which the question is usually asked.

But actually it reflects a demand that the individual take responsibility for society and its institutions.

“What cause do I want to serve?” is implied.

The World is Full of Options The World is Full of Options

Carefully choosing your nonprofit affiliations (beware of scams and inside-out bureaucracies because society suffers the consequences and you are part of society. Carefully choosing your nonprofit affiliations (beware of scams and inside-out bureaucracies because society suffers the consequences and you are part of society.

If they don’t produce the desired results outside of themselves then we have to pay a second or a third or a fourth … organization until we get what is needed.)

And underlying this question is the demand the individual take responsibility for himself.

Managing Oneself then … Managing Oneself then …

The Effective Executive: Preface The Effective Executive: Preface

“What shall I do with myself?” rather than “’What shall I do?” is really being asked of the young by the multitude of choices around them.

The society of organizations forces the individual to ask of himself:

“Who am I?” “Who am I?”

“What do I want to be?” “What do I want to be?”

“What do I want to put into life and what do I want to get out of it?” “What do I want to put into life and what do I want to get out of it?”

read more on how can the individual survive …

The Age of Discontinuity:

Guidelines To Our Changing Society

enhanced by bobembry

... replace the quest for success with the quest for contribution.

(to the society of organizations moving in time — above)

The critical question is not, “How can I achieve?”

but “What can I contribute?”

The Daily Drucker

You can’t design your life around a temporary organization

Successful careers are not planned

They develop when people are prepared

for opportunities

because they know

their strengths,

their method of work, and

their values.

Knowing where one belongs

can transform an ordinary person

—hardworking and competent but otherwise mediocre—

into an outstanding performer.

Larger

Managing Oneself and Living in More than One World

To get the benefits you have to calendarize these

“What do you need to learn to get the most out of your strengths?”

The World is Full of Options

“What do you need to learn so that you can decide where to go next?”

Managing in a Time of Great Change

The three types of intelligence discussed in The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli

Types of behavior that can be observed …

… “Power has to be used.

It is a reality.

If the decent and idealistic toss power in the gutter, the guttersnipes pick it up.

If the able and educated refuse to exercise power responsibly, irresponsible and incompetent people take over the seats of the mighty and the levers of power.

Power not being used for social purposes passes to people who use it for their own ends.

At best it is taken over by the careerists who are led by their own timidity into becoming arbitrary, autocratic, and bureaucratic.”

— How Can The Individual Survive?

The Age of Discontinuity: Guidelines To Our Changing Society

by Peter Drucker

What do you want to be remembered for?

In Landmarks of Tomorrow, Peter Drucker wrote “everyone is an understudy to the leading role in the drama of human destiny” and the “great roles are not written in the iambic pentameter or the Alexandrine of the heroic theater.”

They are, instead, “prosaic — played out in one’s daily life, in one’s work, in one’s citizenship, in one’s compassion or lack of it, in one’s courage to stick on an unpopular principle, and in one’s refusal to sanction man’s inhumanity to man in an age of cruelty and moral numbness.”

Career / life vision guidance from Peter Drucker — extremely, extremely, extremely valuable attention-directing concepts and ideas from a long-term standpoint.

Larger view of the big picture action system

Larger

Larger

“What the new industries and institutions will be, no one can say yet.

No one in the 1520s anticipated secular literature, let alone the secular theater.

No one in the 1820s anticipated the electric telegraph, or public health, or photography.

The one thing (to say it again) that is highly probable, if not nearly certain, is that the next twenty years will see the emergence of a number of new industries.